Dillard v. City of Elba Order Granting Motion for Award of Attorney's Fees

Public Court Documents

October 20, 1993

10 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Dillard v. City of Elba Order Granting Motion for Award of Attorney's Fees, 1993. 4e830025-b8d8-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3c533baa-091f-4798-b43e-6088cfbd95ad/dillard-v-city-of-elba-order-granting-motion-for-award-of-attorneys-fees. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

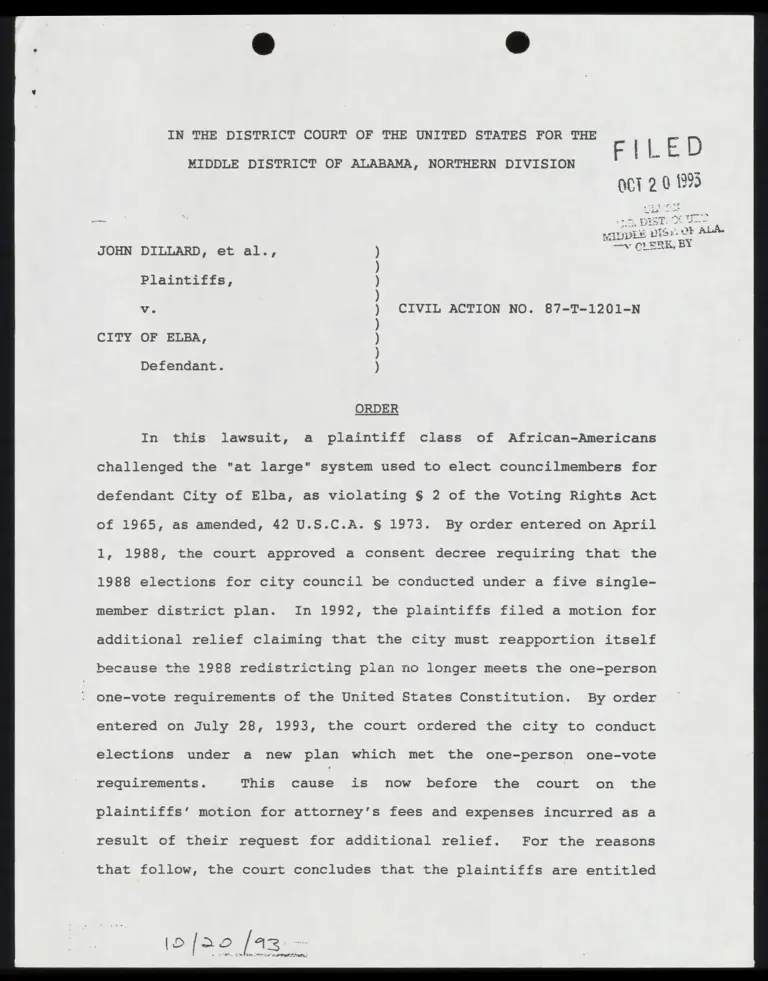

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR THE

FILED

0c 2 0 1993

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, NORTHERN DIVISION

7 AREER

y—r

=e : vm BAST. 2X URS

DEE PIG. OF ALA.

Wades . y RK BY

JOHN DILLARD, et al., v CLERK,

Plaintiffs,

Vv. CIVIL ACTION NO. 87-T-1201-N

CITY OF ELBA,

Defendant.

N

a

t

”

N

a

s

Na

at

N

t

Na

nt

”

st

”

ve

t

“m

at

?

“

i

t

?

ORDER

In this lawsuit, a plaintiff class of African-Americans

challenged the "at large" system used to elect councilmembers for

defendant City of Elba, as violating § 2 of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C.A. § 1973. By order entered on April

1, 1988, the court approved a consent decree requiring that the

1988 elections for city council be conducted under a five single-

member district plan. In 1992, the plaintiffs filed a motion for

additional relief claiming that the city must reapportion itself

because the 1988 redistricting pian no longer meets the one-person

one-vote requirements of the United States Constitution. By order

entered on July 28, 1993, the court ordered the city to conduct

elections under a new plan which met the one-person one-vote

requirements. This ohuss is now before the court on the

plaintiffs’ motion for attorney’s fees and expenses incurred as a

result of their request for additional relief. For the reasons

that follow, the court concludes that the plaintiffs are entitled

n/a g [55 A

to recover $6,670.00 in attorney’s fees and $463.45 in expenses,

for a total of $7,133.45 from the City of Elba.

1.

The plaintiffs seek an award of attorney’s fees under the

Voting Rights Act. The Act provides that

"In any action or proceeding to enforce the

voting guarantees of the fourteenth or

fifteenth amendment, the court, in its

discretion, may allow the prevailing party,

other tnan the United States, a reasonable

attorney’s fee as part of the cost."

42 u.S.C.A. § 19731(e). This provision, which is similar in

substance and purpose to the Attorney’s Fees Act of 1976, serves

the familiar purpose of encouraging private litigants to act as

"private attorneys general" to vindicate their rights and the

rights of the public at large, by guaranteeing to them, if they

prevail, a reasonable attorney’s fee.’ With this provision,

Congress sought to create an alternative means to ensure, without

the expenditure of additional public funds, that the policies

underlying the Voting Rights Act are implemented and enforced

successfully. Guaranteed fees were considered to be essential to

1. 42 U.S.C.A. § 1988. Plaintiffs also seek to recover under

this provision.

2. Indeed, the similarity between the language and underlying

purposes of the fee award provisions of the Voting Rights Act, §

19731(e), the Attorney’s Fees Act of 1976, § 1988, and the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e-5(k), has led the Eleventh

Circuit to conclude that the standards for awarding fees under the

various provisions should be generally the same. Brooks v. Georgia

State Board of Elections, 997 F.2d 857, 861 (11th Cir. 1993);

Maloney v. City of Marietta, 822 F.2d 1023, 1025 n.2 (11th Cir.

1987) (per curiam).

this end in light of concerns over the financial ability of victims

of discrimination to bring such actions and the fact that the

relief sought and obtained is often nonmonetary. Donnell v. United

States, 682 F.2d 240, 245-46 (D.C. Cir. 1982), cert. denied, 459

U.S. 1204, 103 S.Ct. 1190 (1983).

The City of Elba has not questioned that the plaintiffs are

the prevailing parties in this litigation and thus entitled to

reasonable attorney’s fees. Indeed, the city could not do so in

good faith. This lawsuit Is an offshoot of a voting rights case

brought in 1985. Dillard v. Crenshaw County, 640 F.Supp. 1347

(M.D. Ala. 1986); 649 F.Supp. 289 (M.D. Ala. 1986, affirmed in part

and remanded in part, 831 F.2d 246 (11th Cir. 1987), reaffirmed on

remand, 679 F.Supp. 1546 (M.D. Ala. 1988). Two years later, in

1987, the lawsuit was expanded state-wide to include the City of

Elba and 182 other local governing bodies. Dillard v. Baldwin

County Board of Education, 686 F. Supp. 1459, 1461 (M.D. Ala.

1988) (discussing the history of the Dillard litigation). As

previously stated, the plaintiffs entered into a consent decree

with the city requiring that, with the 1988 elections, the city

elect its council members under a single-member distri plan, and

the plaintiffs subsequently prevailed in their effort to have the

city reapportion its districts for the 1993 election to meet the

one-person one-vote requirements. Therefore, the only issue before

the court is what the fee should be.

11.

The starting point in setting any reasonable attorney’s fee is

determining the "lodestar" figure--that is, the product of the

number of hours reasonably expended to prosecute the lawsuit and

the reasonable hourly rate for non-contingent work performed by

similarly situated attorneys in the community. After calculating

the lodestar fee, the court should then proceed with an analysis of

whether any portion of this fee should be adjusted upwards or

downwards. Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424, 433-34, 103 S.Ct.

1933, 1939-40 (1983).

In making the above determinations, the court is guided by the

12 factors set out in Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 488 F.2d

714, 717-19 (5th Cir. 1974). See Blanchard v. Bergeron, 489 U.S.

87, 91-92, 109 S.Ct. 939, 943 (1989); Hensley, 461 U.S. at 434 n.

9, 103 S.Ct. at 1940 n. 9. These factors are: (1) the time and

labor required; (2) the novelty and difficulty of the questions;

(3) the skill required to perform the legal services properly; (4)

the preclusion of other employment by the attorney due to accep-

tance of the case; (5) the customary fee in the community; (6)

whether the fee 1s fixed or contingent; (7) time limitations

imposed by the client or circumstances; (8) the amount involved and

the results obtained; (9) the experience, reputation, and ability

of the attorney; (10) the "undesirability" of the case; (11) the

nature and length of professional relationship with the client; and

(12) awards in similar cases.

A. Reasonable Hours

James U. Blacksher and Edward Still represented the plaintiffs

in this matter. They seek compensation for the following hours:

Blacksher 18.6 hours;

Still 4.4 hours;

The court has considered two Johnson factors--the novelty and

difficulty of the case, and the amount involved and the result

obtained--in assessing the reasonableness of the hours claimed. A

cursory review of such cases as Brown v. Thomson, 462 U.S. 835, 103

S.Ct. 2690 (1983), White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 93 S.Ct. 2332

(1973), and Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 84 S.Ct. 1362 (1964),

would indicate that even the simplest one-person one-vote case

would be formidable to an attorney unfamiliar with the voting

rights law. Because an attorney with less knowledge and experience

than plaintiffs’ attorneys would have taken many more hours to

pursue this litigation, the number of hours claimed could be viewed

as conservative. The court finds, in light of these circumstances,

that all the hours expended and claimed were not "excessive, redun-

dant, or otherwise unnecessary," Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S.

424, 434, 103 S.Ct. 1933, 1939-40 (1983), but were necessary, and

directly related, to securing the relief obtained. Blacksher and

Still are entitled to the full number of hours claimed.

B. Prevailing Market Rate

"A reasonable hourly rate is the prevailing market rate in the

relevant legal community for similar services by lawyers of

reasonably comparable skills, experience, and reputation." Norman

v. Housing Authority of Montgomery, 836 F.2d 1292, 1299 (11th Cir.

1988). To determine the prevailing market rate, the court will

consider the following Johnson factors: customary fee; skill

Tequired to perform the legal services properly; the experience,

reputation and ability of the attorney; time limitations; pre-

clusion of other employment; contingency; undesirability of the

case; nature and length of professional relationship with the

client; and awards in similar cases.

Customary Fee: The plaintiffs contend that the customary fee

for an attorney of similar experience in the community supports an

hourly non-contingent fee of $350 for Blacksher and Still. The

evidence shows that Alabama attorneys practicing in the same and

similar areas of law with approximately the same experience and

skill as plaintiffs’ attorneys charge a non-contingent fee of at

least $290 an hour.’

Skill Required to Perform the legal Services Properly: It

cannot be questioned that voting rights litigation requires a

highly skilled attorney. As explained earlier, even the simplest

3. As originally envisioned by Congress, civil rights

attorneys were to be paid on a par with commercial lawyers. See S.

Rep. No. 1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 6 (1976), 1976 U.S. Code Cong.

& Admin. News 5913 ("It is intended that the amount of fees awarded

under [§ 1988] be governed by the same standards which prevail in

other types of equally complex Federal litigation, such as

antitrust cases[,] and not be reduced because the rights involved

may be nonpecuniary in nature.") Regrettably, this has not proved

to be true. Indeed, if upon completion of law school, plaintiffs’

attorneys chosen to devote themselves to commercial rather than

public interest law, they would today, in light of their abilities,

be able to command a substantially higher hourly rate.

6

voting rights case would be daunting to an attorney who had not

specialized in voting rights law.

Experience, Reputation, and Ability of the Attorney: Blacksher

and Still have now rightfully earned the reputation as two of the

most experienced, knowledgeable, and able voting rights lawyers in

the State of Alabama, if not the nation. They have to their credit

such trail-blazing cases as Bolden v. City of Mobile, 423 F.Supp.

384 (S.D. Ala. 1976), aff'd 571 F.2d 238 (5th Cir. 1978), reversed

and remanded, 446 U.S. 55, 100 S.Ct. 1490 (1980), reaffirmed on

remand, 542 F.Supp. 1050 (S.D. Ala. 1982), and Hunter v. Underwood,

471 U.S. 222, 105 S.Ct. 1916 (1985). Blacksher has also written

extensively in the area. See, e.g., J. Blacksher and L. Menefee,

"At-Large Election and One Person, One Vote: The Search for the

Meaning of Racial Vote Dilution," in Minority Vote Dilution (C.

Davidson ed.) (1984).

Time Limitations: Where there has been "[p]riority work that

delays the lawyer’s other legal work," this factor requires "some

premium." Johnson, 488 F.2d at 718. The case was litigated under

the pressure of an impending election.

Preclusion of Other Emplovment: This factor "involves the

dual consideration of otherwise available business which is

foreclosed because of conflicts of interest which occur from the

representation, and the fact that once the employment is undertaken

the attorney is not free to use the time spent on the client's

behalf for other purposes." Johnson, 488 F.2d at 718. There is no

evidence to support this factor.

Contingency. Plaintiffs have not sought an enhancement based

on contingency.

Undesirability of the Case: In general, civil rights litiga-

tion is seen "as very undesirable because it stigmatizes an

‘attorney as a ‘civil rights lawyer’ and thus tends to deter fee-

paying clients, particularly high-paying commercial clients, from

seeking assistance from that lawyer." Stokes v. City of Mont-

gomery, 706 F.Supp. 811, 815 (M.D. Ala. 1988), aff'd, 891 F.2d 905

{11th Cir. 1989) (table).* The results of such litigation tend to

arouse the emotions of all concerned, and frequently the attorneys

who bring these cases are the subjects of prolonged and vitriolic

hostility.

Nature and Length of Relationship with Client. Blacksher and

Still have represented the plaintiffs in this matter from its

inception. There is no evidence that they had a prior professional

relationship with the plaintiffs, except to the extent that they

have represented the plaintiffs in all these Dillard cases.

Awards in Similar Cases: Blacksher and Still were awarded

$350 an hour in another voting rights case. Lawrence v. City of

Talladega, civil action no. 91-C-1340-M (N.D. Ala. May 17, 1993).

The court is of the opinion, based on these criteria, that the

prevailing market rate for non-contingent work performed by

attorneys of similar knowledge and experience in similar cases is

4. See also Robinson v. Alabama State Department of Educa-

tion, 727 F.Supp. 1422 (M.D. Ala. 1989), aff'd 918 F.2d 183 (11th

Cir. 1990) (table); Hidle v. Geneva County Board of Education, 681

F.Supp. 752, 756 (M.D. Ala. 1988); York v. Alabama State Board of

Education, 631 F.Supp. 78, 85 (M.D. Ala. 1986).

8

at least $290 an hour.’

C. Lodestar Calculation

The unadjusted lodestar for an attorney consists, as stated,

of the product of the attorney’s compensable hours multiplied by

his prevailing market fee. The lodestars for plaintiffs’ counsel

are therefore as follows:

Blacksher 18.5 hours x $290 $ 5,394

Still 4.4 hours x $290 = 1.276

Total S$ 6,670

D. Adjustment

An adjustment neither upward nor downward is warranted.

III.

Plaintiffs’ counsel also seek an award of $463.45 for certain

expenses. With the exception of routine overhead office normally

absorbed by the practicing attorney, all reasonable expenses

incurred in case preparation, during the course of litigation, or

as an aspect of settlement of the case may be taxed as costs under

section 1988 and the standard of reasonableness is to be given a

5. By establishing the appropriate market rate on the basis

of current rates, the court is also compensating plaintiffs’

counsel for the delay in payment. See Missouri v. Jenkins, 491

U.S. 274, 284, 109 S.Ct. 2463, 2469 (1989) ("an appropriate

adjustment for delay in payment--whether by the application of

current rather than historic hourly rates or otherwise--is within

the contemplation of the statute"); Norman, 836 F.2d at 1302 ("[i]n

this circuit, where there is a delay the court should take into

account the time value of money and the effects of inflation and

generally award compensation at current rates rather than at

historic rates").

liberal interpretation. Loranger v. Stierheim, F.3d +1993

WL 330598 (11th Cir. Sept. 28, 1993); NAACP v. City of Evergreen,

812 F.2d 1332, 1337 (11th Cir. 1987). Expenses claimed in this

matter include costs for a demographer, long distance calls, and

travel. a1 of these expenses appear to be reasonable and

necessary. The court therefore determines that plaintiffs’ counsel

may recover all the expenses requested.

It is therefore the ORDER, JUDGMENT, and DECREE of the court

that the plaintiffs’ moticn for award of attorney’s fees, filed

September 1, 1993, is granted, and that the plaintiffs have and

recover from defendant City of Elba the sum of $6,670.00 as

attorney’s fees and $463.45 for expenses, for a total sum of

$7,133.45.

DONE, this the 20th day of October, 1993.

vd Oo

UNYTED STATE DISTRICT JUDGE