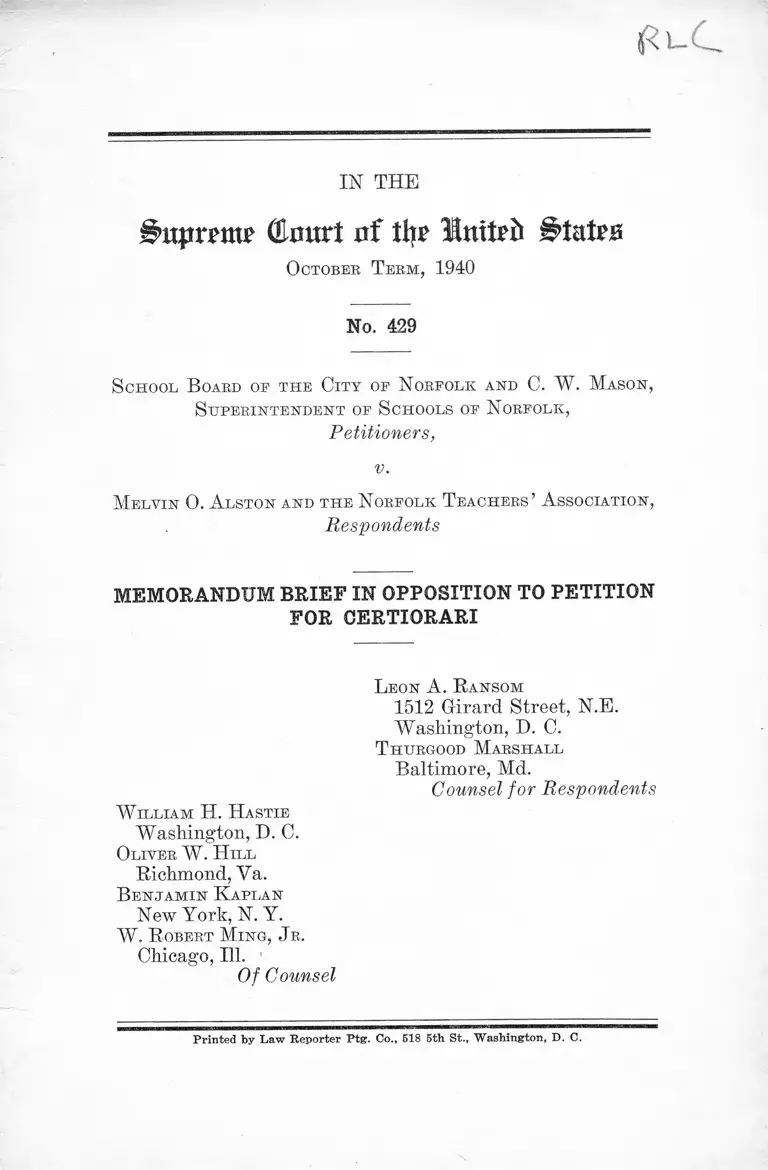

City of Norfolk School Board v. Alston Memorandum Brief in Opposition to Petition for Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1940

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of Norfolk School Board v. Alston Memorandum Brief in Opposition to Petition for Certiorari, 1940. c63705ae-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3c591284-2bc5-41c0-8c96-b7e9ecca3fa7/city-of-norfolk-school-board-v-alston-memorandum-brief-in-opposition-to-petition-for-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

g>uprpmp (Unurt nf % Irntpfc States

O ctober T erm , 1940

IN THE

No. 429

S chool B oard of the C ity of N orfolk and C. W . M ason,

S uperintendent of S chools of N orfolk,

Petitioners,

v.

M elvin 0 . A lston and the N orfolk T eachers ’ A ssociation,

Respondents

MEMORANDUM BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION

FOR CERTIORARI

L eon A . R ansom

1512 Girard Street, N.E.

Washington, D. C.

T hurgood M arshall

Baltimore, Md.

Counsel for Respondents

W illiam H . H astie

Washington, D. C.

O liver W. H ill

Richmond, Va.

B e n jam in K aplan

New York, N. Y.

W . R obert M ing , J r .

Chicago, 111.

Of Counsel

Printed by Law Reporter Ptg. Co., 518 5th St., Washington, D. C.

SUBJECT INDEX

PAGE

Statement of Facts___________________________________ 1

Questions Involved___________________________________ 3

Argument

I. The decision that the alleged salary discrimination

is a denial of equal protection of the laws is so

clearly sound and consistent with precedent that

it should not be reviewed______________________ 3

A. There is no conflict in the federal decisions

on this proposition_____________________ 3

B. There is no conflict between the decision

of the Circuit Court of Appeals and ap

plicable local decisions________________ 4

C. The decision of the Circuit Court of Appeals

is consistent with the course of decisions

of this court construing the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States_________________________ 5

II. The issue of waiver should not be reviewed upon

the present record____________________________ 6

Conclusion ____________________________________ ____ _ 9

TABLE OF CASES

PAGE

Black v. School Board of the City of Norfolk (Unre

ported) ___________________________________________ 5

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60______________________ 6

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339_______________________ 6

Gaines v. Missouri, 305 U. S. 337_______________________ 6

Gilbert v. Highfill, — Fla. —, 190 So. 813______________ 5

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268__________________________ 6

McCabe v. A. T. & Santa Fe Ry. Co., 235 U. S. 151_______ 6

Mills v. Anne Arundel County Board of Education, et al.,

30 F. Supp. 245____________ __ _____________________ 4

Mills v. Lowndes, et ah, 26 F. Supp. 792_______________ 4

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73_________________________ 6

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354_______________ _______ 6

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303____________ 6

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33_________ ....________________ 6

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 220_____________________ 6

Yu Cong Eng v. Trinidad, 271U. S. 500_________________ 6

STATUTES AND RULES CITED

Virginia Code:

Section 664 ____________________________________ 7

Section 786 ____________________________________ 7

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure:

Rule No. 7 (a )__________________________________ 8

Rule No. 8 (c )__________________________________ 8

IN THE

Supreme (Emtrt of tl}2 Imtpfr Binits

O ctober T eem , 1940

No. 429

S chool B oaed of th e Cit y of N orfolk and C. W . M ason,

S uperintendent of S chools of N orfolk,

Petitioners,

v.

M elvin 0 . A lston and th e N orfolk T eachers ’ A ssociation,

Respondents

MEMORANDUM BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION

FOR CERTIORARI

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice, and the Associate

Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States:

In opposing the petition for certiorari filed by petitioners

herein, respondents respectfully show:

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Petitioners seek review of a judgment rendered upon

pleadings. The judgment does not accomplish a final dis

position of the case but merely decides that the complaint

is legally sufficient and orders a trial of the controversy for

the first time on its merits.

Respondents as plaintiffs in the District Court of the

United States for the Eastern District of Yirginia filed their

complaint against the defendant School Board and the

defendant Superintendent of Schools seeking a permanent

2

injunction against, and a judgment declaratory of, alleged

unconstitutional racial discrimination in administratively

established schedules of salaries for white and colored

teachers in the City of Norfolk and in the salaries actually

paid pursuant to such schedules. The essence of the com

plaint appears in paragraphs 11 and 12 thereof where it

is alleged that:

“ 11. Defendants over a long period of years have con

sistently pursued and maintained and are now pursuing

and maintaining the policy, custom, and usage of pay

ing Negro teachers and principals in the public schools

of Norfolk less salary than white teachers and prin

cipals in said public school system possessing the same

professional qualifications, certificates and experience,

exercising the same duties and performing the same

services as Negro teachers and principals. Such dis

crimination is being practiced against the plaintiffs and

all other Negro teachers and principals in Norfolk,

Virginia, and is based solely upon their race or color.”

‘ ‘ 12. The plaintiff Alston and all of the members of the

plaintiff association and all other Negro teachers and

principals in public schools in the City of Norfolk are

teachers by profession and are specially trained for

their calling. By rules, regulations, practice, usage

and custom of the Commonwealth acting by and through

the defendants and its agents and agencies, the plain

tiff Alston and all of the members of the plaintiff asso

ciation and all other Negro teachers and principals in

the City of Norfolk are being denied the equal protec

tion of the laws in that solely by reason of their race

and color they are being denied compensation from

public funds for their services as teachers equal to the

compensation provided from public funds for and being

paid to white teachers with equal qualifications and

experience for equivalent services pursuant to rules,

regulations, custom and practice of the Commonwealth

acting by and through its agents and agencies, the

School Board of the City of Norfolk and the Superin

tendent of Schools of Norfolk, Virginia. ’ ’ (Record,

pp. 7, 8.)

3

As appears in the judgment of the District Court (Record,

pp. 30-31), the cause came on, at the suggestion of the Dis

trict Judge, for preliminary hearing solely upon the issue

of the legal sufficiency of the complaint as raised by so much

of the answer as was in the nature of a motion to dismiss.

Upon such hearing the District Court entered a final order

sustaining the motion to dismiss the complaint. From that

order the respondents appealed. The Circuit Court of Ap

peals for the Fourth Circuit reversed the judgment of the

District Court and remanded the cause for trial (Record,

p. 45).

QUESTIONS INVOLVED

I. THE DECISION THAT THE ALLEGED SALARY

DISCRIMINATION IS A DENIAL OF EQUAL PRO

TECTION OF THE LAWS IS SO CLEARLY SOUND

AND CONSISTENT W ITH PRECEDENT THAT IT

SHOULD NOT BE REVIEWED.

II. THE ISSUE OF W AIVER SHOULD NOT BE

REVIEWED UPON THE PRESENT RECORD.

ARGUMENT

I

The Decision That the Alleged Salary Discrimination Is a

Denial of Equal Protection of the Laws Is So Clearly

Sound and Consistent With Precedent That

It Should Not Be Reviewed

A. There Is No Conflict in the Federal Decisions on This

Proposition

On the three other occasions that federal courts have

passed on this question the decisions have been in accord

with the conclusion reached by the Circuit Court of Appeals

that:

4

“Plaintiffs, as teachers qualified and subject to employ

ment by the state, are entitled to apply for the posi

tions and to have the discretion of the authorities exer

cised lawfully and without unconstitutional discrimina

tion as to the rate of pay to be awarded them, if their

applications are accepted.” (Record, p. 43.)

Even the District Court conceded that:

“ The authorities are clear—that there can be no dis

crimination in a case of this kind, if such discrimina

tion is based on race or color alone.” (Record, p. 24.)

The only other federal court in which the question has

been raised is that of the United States District Court for

the District of Maryland. That court twice reached the

same conclusion.

Mills v. Lowndes et al., 26 P. Supp. 792 (1939);

Mills v. Anne Arundel County Board of Education et

al., 30 F. Supp. 245 (1939).

In the latter case the Court said:

“ . . . As already stated, the controlling issue of fact

is whether there has been unlawful discrimination by

the defendants in determining the salaries of white

and colored teachers in Anne Arundel County solely

on account of race or color, and my finding from the

testimony is that this question must be answered in the

affirmative, and the conclusion of law is that the plain

tiff is therefore entitled to an injunction against the

continuance of this unlawful d is cr im in a tio n (Italics

supplied.) (30 Fed. Supp. at 252.)

B. There Is No Conflict Between the Decision of the Circuit

Court of Appeals and Applicable Local Decisions

Although no question of local law is here presented since

the right claimed by the respondents is one guaranteed by

the Constitution of the United States, actually there is no

5

decision of a state court in conflict with that of the Circuit

Court of Appeals here.

In the only reported state case, Gilbert v. Highfill, Fla.

—, 190 So. 813 (1939), mandamus was sought to compel the

adoption of an equal salary schedule for white and Negro

teachers. The Supreme Court of Florida held that manda

mus would not lie to compel the adoption of any salary

schedule, expressly stating however, at page 815:

“ We fully agree with counsel for the relator and the

authorities cited in their brief on the question of dis

crimination and an equal protection of the law as guar

anteed by the 14th Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States, U. S. C. A. We do not think either

of these questions is presented by the record.” (Italics

supplied.)

In the unreported case of Aline Black v. The School Board

of the City of Norfolk et al., the Circuit Court of the City

of Norfolk considered a demurrer to a similar petition for

mandamus and ruled that mandamus was not the proper

remedy. No mention was made of the substantive question

here involved. (Record, p. 23.)

Similar actions filed in the Maryland counties of Mont

gomery, Prince George’s and Calvert were made moot

before trial by equalization of salaries pursuant to agree

ment.

Thus the state courts upon whose decisions petitioners

rely have passed only on the procedural question and have

not adjudicated the substantive question involved here.

C. The Decision of the Circuit Court of Appeals Is Con

sistent With the Course of Decisions of This Court

Construing the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States.

It is submitted that certiorari should not be granted be

cause the judgment of the Circuit Court of Appeals is clearly

6

sound, consistent with, and follows closely a long line of

precedents established by this Court.

A general effect of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States is to prohibit arbitrary and

unreasonable classification by state agencies.

Yu Cong Eng v. Trinidad, 271 U. S. 500 (1926);

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33 (1915);

Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 220 (1886).

Discrimination because of race or color is clearly arbi

trary and unreasonable. This Court has repeatedly so held

in cases arising out of a variety of factual situations.

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 (1939);

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354 (1939) ;

Gaines v. Missouri, 305 U. S. 337 (1938);

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73 (1932);

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917);

McCabe v. A. T. & Santa Fe By. Co., 235 U. S. 151

(1914);

Strauder v. W. Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1879);

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339 (1879).

By the motion to dismiss petitioners have admitted that

the existing salary differentiation is based solely on the race

and color of the respondents and that it is adopted, main

tained and enforced by petitioners acting for the Common

wealth of Virginia.

The Circuit Court of Appeals has logically applied the

doctrine established by this Court to the facts of the instant

case.

II

The Issue of Waiver Should Not Be Reviewed Upon the

Present Record

Respondents agree with petitioners that it is an impor

tant Federal question whether Negroes who accept employ

ment as public school teachers thereby waive their right to

7

complain that they are denied the equal protection of the

laws by salary discrimination based solely upon race and

imposed and required by rule, regulation and practice of

an agency of the State. However, neither the present state

of the record upon that issue nor the scope of the decision

of the Circuit Court of Appeals warrants the granting of

certiorari.

Paragraph 10 of the complaint (Record, p. 7) alleges that

defendants, petitioners here, are under a statutory duty to

employ teachers and to provide for the payment of their

salaries, citing, inter alia, Section 786, of the Virginia Code

of 1936 which provides in part that

“ The City school board of every city shall . . . have

the following powers and duties . . . Third. To em

ploy teachers . . . Twelfth. To . . . provide for the

pay of teachers . . . ”

It is further provided in Section 664 that

“ Written contracts shall be made by the school board

with all public school teachers before they enter upon

their duties, in a form to be prescribed by the Superin

tendent of Public Instruction.”

Paragraph 15 of the complaint (Record, p. 9) alleges that

plaintiff Alston, respondent here,

“ is being paid by the defendants for his services this

school year as a regular male high school teacher as

aforesaid an annual salary of $921.”

Thus, from the complaint and the above quoted language

of applicable Virginia statutes it seems a proper conclusion

that respondent Alston is employed during the current year

pursuant to a contract of hire and at an annual salary of

$921. Moreover, in a preliminary proceeding in the nature

of a hearing on motion to dismiss the complaint it was

proper that the court determine whether any conclusion of

law fatal to the respondents’ ease followed from the facts

outlined above. To that extent, and to that extent only, the

question of waiver was before the District Court and the

Circuit Court of Appeals.

It is to be noted that so much of the “ Second Defense”

in the answer as raises the issue of waiver is in form

a defense in law in the nature of a motion to dismiss, but

in substance it combines a challenge to the sufficiency of the

complaint with an introduction of new matter in the nature

of an affirmative defense. Thus, the sub-paragraphs num

bered (4) and (5) (Record, p. 19) go beyond an allegation

that acceptance of employment by the respondent is a

waiver of the rights asserted in his complaint. These sub-

paragraphs refer to the specific contract of the respondent

and incorporate by reference an attached document de

scribed as a copy of his contract. In thus going beyond the

fact of employment pursuant to a contract of hire as already

revealed by the complaint and pertinent statutes, and in

attempting to put in issue the terms of a particular con

tract, the circumstances of its execution and any legal con

clusions that may depend upon such terms and circum

stances, the petitioners introduced an affirmative defense.

Under Rule 8(c) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

such new matter is deemed to be denied without reply.

Indeed, no reply is permitted except by order of the Court.

See Rule 7(a). Therefore, the new matter alleged in the

answer was not before the court on a motion to dismiss

and is not material at the present stage of this litigation.

In brief, the question before the Circuit Court of Appeals

was whether the facts (1) that respondent’s status had been

created by a contract of hire and (2) that he had been em

ployed for a definite salary, operated as a matter of law to

preclude this suit.

With the issue thus defined and restricted the Circuit

Court of Appeals concluded that no waiver had been shown

and remanded the case for trial.

9

The petition for certiorari neither comprehends the issue

thus outlined nor suggests any reason for the review of the

decision thereon. None of the parties will suffer any legal

detriment from the order of the Circuit Court of Appeals

requiring a trial of the entire cause on its merits. Questions

of law can then be considered in the light of all material

facts. Whatever the event of such a trial may be, the dis

satisfied party or parties will be in position to ask that the

issue of waiver be reviewed, along with any other matters in

controversy, upon the complete record.

CONCLUSION

In such circumstances neither public interest nor the

interests of the litigants will be served by the granting of

certiorari as now prayed; but, on the other hand, orderly

and complete disposition of this litigation can best be accom

plished by remanding the cause for trial as ordered by the

Circuit Court of Appeals.

Wherefore, we respectfully submit that the petition for

certiorari should be denied.

L eon A . R ansom

1512 Girard Street, N.E.

Washington, D. C.

T hiibgood M abshall

Baltimore, Md.

Counsel for Respondents

W illiam H . H astie

Washington, D. C.

Oliveb W . H ill

Richmond, Va.

B e n ja m in K aplan

New York, N. Y.

W . R obebt M ing , Jb.

Chicago, 111.

Of Counsel