Defense Fund Asks U.S. Supreme Court to Reverse Freedom Rider Convictions

Press Release

June 16, 1964

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Defense Fund Asks U.S. Supreme Court to Reverse Freedom Rider Convictions, 1964. 589aec8b-bd92-ee11-be37-6045bddb811f. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3c5fc84b-6e92-403c-a60f-c98f8b717130/defense-fund-asks-us-supreme-court-to-reverse-freedom-rider-convictions. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

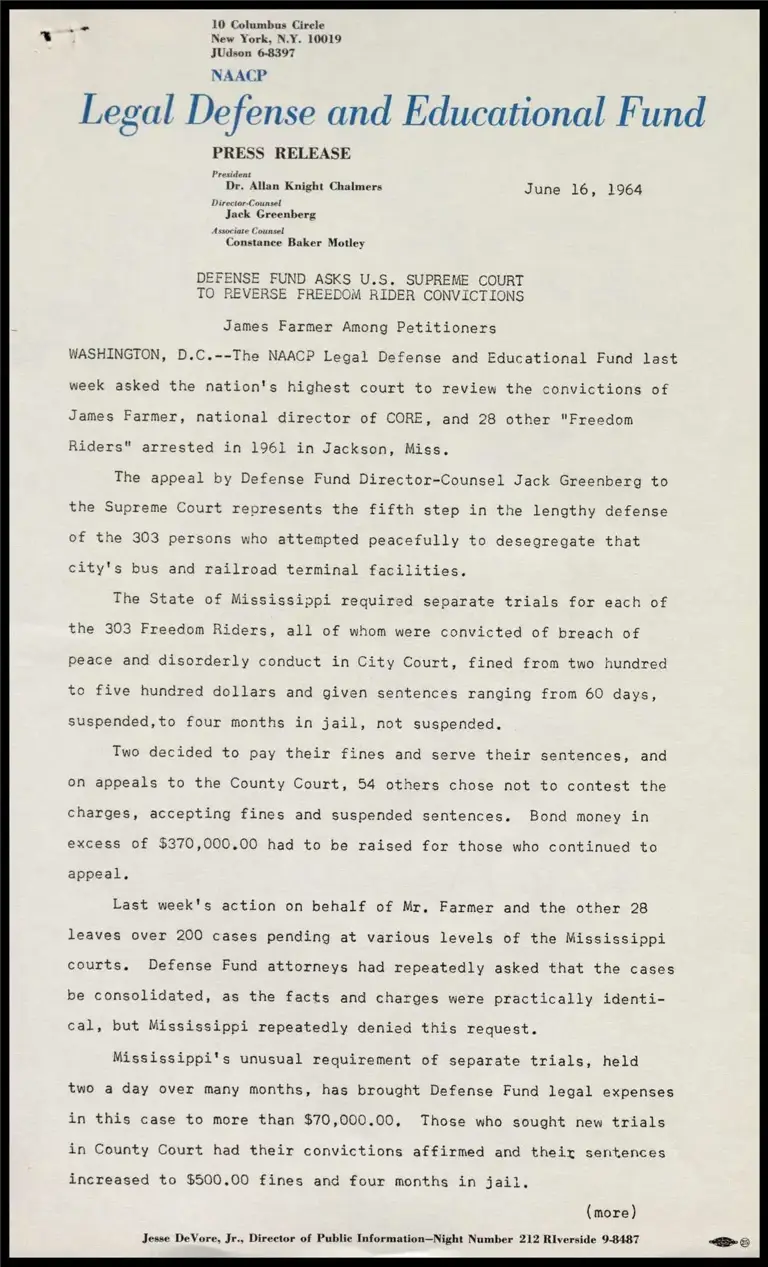

_ 10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

JUdson 6-8397

NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund

PRESS RELEASE

President

Dr. Allan Knight Chalmers June 16, 1964

Director-Counsel

Tack Ceeenhere

Associate Counsel

Constance Baker Motley

DEFENSE FUND ASKS U.S. SUPREME COURT

TO REVERSE FREEDOM RIDER CONVICTIONS

James Farmer Among Petitioners

WASHINGTON, D.C.--The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund last

week asked the nation's highest court to review the convictions of

James Farmer, national director of CORE, and 28 other "Freedom

Riders" arrested in 1961 in Jackson, Miss.

The appeal by Defense Fund Director-Counsel Jack Greenberg to

the Supreme Court represents the fifth step in the lengthy defense

of the 303 persons who attempted peacefully to desegregate that

city's bus and railroad terminal facilities.

The State of Mississippi required separate trials for each of

the 303 Freedom Riders, all of whom were convicted of breach of

peace and disorderly conduct in City Court, fined from two hundred

to five hundred dollars and given sentences ranging from 60 days,

suspended,to four months in jail, not suspended.

Two decided to pay their fines and serve their sentences, and

on appeals to the County Court, 54 others chose not to contest the

charges, accepting fines and suspended sentences. Bond money in

excess of $370,000.00 had to be raised for those who continued to

appeal,

Last week's action on behalf of Mr, Farmer and the other 28

leaves over 200 cases pending at various levels of the Mississippi

courts. Defense Fund attorneys had repeatedly asked that the cases

be consolidated, as the facts and charges were practically identi-

cal, but Mississippi repeatedly denied this request.

Mississippi's unusual requirement of separate trials, held

two a day over many months, has brought Defense Fund legal expenses

in this case to more than $70,000.00, Those who sought new trials

in County Court had their convictions affirmed and their sentences

increased to $500.00 fines and four months in jail.

(more)

Jesse DeVore, Jr., Director of Public Information—Night Number 212 Rlverside 9-8487 ee)

Defense Fund Asks U,S. Supreme Court -2- June 16, 1964

to Reverse Freedom Rider Convictions

The cases continued at snail's pace on appeals to the Circuit

Court and the Mississippi Supreme Court throughout 1962 and 1963.

The state courts consistently refused to consider the constitu-

tional arguments raised by Defense Fund lawyers, and in March of

this year the Mississippi Supreme Court affirmed the convictions

appealed last week,

: Jackson Police Captain J.L. Ray, who made the arrests imme-

diately upon the arrival of the racially mixed groups at the

terminals of the Greyhound and Trailways bus lines and the Illinois

Central Railroad Station, repeatedly testified that the defendants

were at all times peaceful.

It was their "presence," their refusal to leave the terminals,

that was offered as evidence of guilt. Captain Ray cited the

"ugly and angry" mood of gathered white persons as a reason for

asking the Freedom Riders to leave, but at no time did he arrest

any of those who threatened to create disturbances.

Among the defendants are several whose bus was overturned

and burned near Anniston, Ala. on the way to Jackson. Others ar-

rived by train from Memphis in the drive to test interstate travel

facilities throughout the South,

In support of the appeal submitted last.week to the U.S,

Supreme Court, Legal Defense Fund attorneys made the following

points:

*the convictions violate due process of law, as guaranteed

by the Fourteenth Amendment, in that the records show no

evidence of guilt;

*the convictions violate due process of law, since the breach

of the peace statute is so vague as to give no ascertainable

standard of guilt, and fails to warn of the conduct punishable;

*the arrests, prosecutions, and convictions fly in the face

of due process and equal protection of the laws, since they

were “designed to enforce racial segregation required by

state statutes and by ordinance of the City of Jackson in

interstate facilities;"

(more)

Defense Fund Asks U.S. Supreme Court -3- June 16, 1964

to Reverse Freedom Rider Convictions

*the convictions violate the First and Fourteenth Amend-

ments, since the Freedom Riders were exercising their

rights of free expression and assembly in their peaceful

actions;

*the prosecutions violated the "Commerce Clause" of the U.S.

Constitution (Art. 1, Sect. 8, clause 3), since they

placed an illegal burden on commerce. Federal law forbids

racial discrimination in interstate travel facilities,

The State now has a month in which to reply to the Defense

Fund brief, after which the high court will decide whether or

not it will review the convictions. Because of the summer recess,

a decision is not likely until after the Court convenes in the

fall.

Joining Director-Counsel Greenberg in the appeal were James

M, Nabrit III and Derrick A. Bell of the Defense Fund's New York

headquarters, and Jack Young, Carsie A, Hall and R,. Jess Brown,

Fund cooperating attorneys in Jackson.

Messrs. Young, Hall and Brown are the only lawyers in the

entire state of Mississippi who handle civil rights cases.

Of counsel in the proceedings were Carl Rachlin, general

counsel of CORE, and Leroy D. Clark and Michael Meltsner of the

Legal Defense Fund.

- 30 -