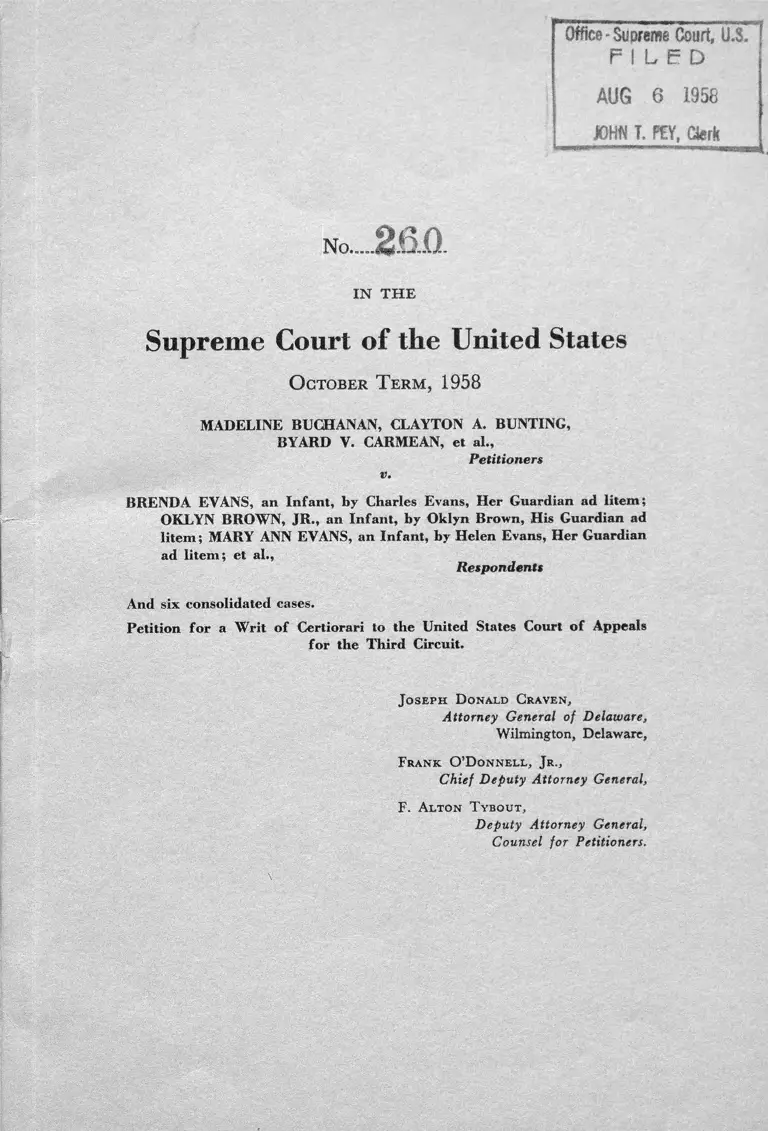

Buchanan v. Evans Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

August 6, 1958

43 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Buchanan v. Evans Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1958. 3b301701-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3c847acf-c8af-4294-a0c3-e6cd862a7113/buchanan-v-evans-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

Office-Supreme Court, i l s T j

P I L E D

A U G 6 1958

JO H N T , F E Y , Clerk

g îl^Wan^iSMwwMwnw w w

IN T H E

Supreme Court of the United States

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1958

MADELINE BUCHANAN, CLAYTON A. BUNTING,

BYARD V. CARMEAN, et al.,

Petitioners

BRENDA EVANS, an Infant, by Charles Evans, Her Guardian ad litem;

OKLYN BROWN, JR., an Infant, by Oklyn Brown, His Guardian ad

litem; MARY ANN EVANS, an Infant, by Helen Evans, Her Guardian

ad litem; et al.,

Respondents

And six consolidated cases.

Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Third Circuit.

Jo se p h D on ald C raven ,

Attorney General of Delaware,

Wilmington, Delaware,

Fr a n k O ’D o n n e l l , Jr .,

Chief Deputy Attorney General,

F. A lt o n T y bo u t ,

Deputy Attorney General,

Counsel for Petitioners.

1

INDEX

Page

Citations to Opinions Below — ...... ........-.............................. 4

Jurisdiction ------- ------------------ ---------- -------------- ----------- 5

Questions Presented....... ............... .............. ...... ........ ....... 5

Statutes Involved_____________ _______________ _____ 5

Basis for Federal Jurisdiction..... ............ ......................— 5

Statement of the Case................................................ ....... 6

Reasons for Granting the Writ ________ ___ _________ _ 10

Conclusion ......................... ............... ............... ............... 15

Appendix: A. Opinions Below ________________ ____ 1(a)

CITATIONS

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686 (1954) ...................................................

Brenda Evans, et al., v. Members of the State Board of Education, et al

145 F. Supp. 873 (D. C. Del., 1956) ..................................................

Brenda Evans, et al. v. State Board, et al.

149 F. Supp. 376 (D. C. Del., 1957) .......................................... .......

Brenda Evans, et al. v. State Board, et al.

152 F. Supp. 886 (D. C. Del., 1957) ...................................................

Brenda Evans, et al. v. State Board, et al.

........F. 2 d ........ , Appendix, p. 15a (C. A., 3rd, 1958) .....................

Stiener v. Simmons

........Del............, 111 A. 2d 574 (1955) at 582 ...................................

STATUTES

14 Delaware Code §101, §105, §107, §108, §121, §122, §141, §301, §302,

§305, §505, §702, §741, §742, §746, §902, §941, §944, §976, §1401,

§1410...................................................................................................................... 5

28 U. S. C. §1343, §1331. ......................................................................................... 5

6

7, 10

7, 11

9, 13

13

12

3

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

NO. _______

O ctober T e r m , 1958

MADELINE BUCHANAN, CLAYTON A. BUNTING,

BYARD V. CARMEAN, et al,

Petitioners

v.

BRENDA EVANS, an Infant, by Charles Evans, Her

Guardian ad litem; OKLYN BROWN, JR., an Infant,

by Oklyn Brown, His Guardian ad litem; M ARY ANN

EVANS, an Infant, by Helen Evans, Pier Guardian

at litem; et al.,

And six consolidated cases.

Respondents

PETITION FOR A W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TH IRD CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Third Circuit entered in each of these cases on May 28,

1958.

The cases below involved seven suits brought by vari

ous Negro minor children to secure admission to schools in

seven different school districts in Delaware. For purposes of

brevity, only the first of these cases is listed in the caption to

this case. The remaining cases are:

Madeline Buchanan, et al., Petitioners

v.

Madeline Staten, et al., Respondents

Madeline Buchanan, et al., Petitio7iers

v.

4

Julie Coverdale, et al., Respondents

Madeline Buchanan, et al., Petitioners

v.

Eyvonne Holloman, et al., Respondents

Madeline Buchanan, et al., Petitioners

v.

David Creighton, et al., Respondents

Madeline Buchanan, et al., Petitioners

v.

Marvin Denson, et al., Respondents

Madeline Buchanan, et al., Petitioners

v.

Thomas J. Oliver, Jr., et al., Respondents

The cases were consolidated both in the District Court and

in the Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. They were

briefed and argued together. The decision in the Third Cir

cuit was the decision in all cases and, at this time, the State

Board of Education is seeking a petition for the writ of

certiorari in all of these cases.

CITATIONS TO OPINIONS BELOW

The first opinion of the District Court, (R .sb p. 15a-

19a)* which was upon the motion of the present respondents

in Case No____ in this Court, printed in Appendix hereto,

page la, is reported in 145 F. Supp. 873. The second de

cision of the District Court in the same case, printed in Ap

pendix hereto, page 6a, is reported in 149 F. Supp. 376. The

third opinion of the District Court, printed in Appendix

hereto, page 10a, is reported at 152 F. Supp. 886. The

opinion of the Court of Appeals, which is in the Record and

* Hereafter “ R.sb” refers to that part of the record which is the appendix of the State

Board’s brief in the Court of Appeals. “ R.pb” refers to appendix to plaintiff’ s brief.

is printed in Appendix p. 15a, hereto, is reported in ........F.

2d ____

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

May 28, 1958 and is a part of the record. Rehearing was

denied on June 20, 1958. The jurisdiction of this Court is

invoked under 28 U. S. C., Section 1254 (1).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether a United States Court can, in furtherance

of certain civil rights of the respondents guaranteed by the

United States Constitution, alter the organization of the

administration of education in Delaware and interpret the

education administration statutes of Delaware and increase

or decrease the responsibility and authority of the various

school boards contrary to the law of Delaware.

2. Whether the Court of Appeals properly determined

the responsibility of the Delaware State Board of education

to draw plans of desegregation of Delaware schools.

STATUTES INVOLVED

The statutes involved are those of Title 14 of the Dela

ware Code. No one statute is in issue but all of those which

go to the administration of Delaware schools. These statutes

are set out at length in the Record and are specifically, Title

14, Delaware Code, Sections 101, 105, 107, 108, 121, 122,

141, 301, 302, 305, 505, 702, 741, 742, 746, 902, 941, 944,

976, 1401, 1410. (R .s b , p. 32a)

BASIS FOR FEDERAL JURISDICTION

Jurisdiction in the Court originally was invoked under

28 U. S. C. §1343 and §1331. The District Court, Wright J.,

5

6

(Appendix, p. la) considered jurisdiction under each sec

tion and determined that, since jurisdiction existed under 28

U. S. C. §1343, it was unnecessary to determine whether the

jurisdiction also existed under 28 U. S. C. §1331.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.

After the United States Supreme Court decision in

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483, 74

S. Ct. 686 (1954), the State Board of Education of Delaware

promptly moved to comply with that decision. Regulations

were instituted requiring local boards to submit plans for

desegregation to the State Board. In many school districts

there was prompt compliance. The State Board approved

the plans submitted, and by 1956 over one-half of the State’s

population was living in areas with desegregated schools.

In many areas, however, the local boards failed to sub

mit, or refused to submit, plans for desegregation. In these

areas, when Negro students demanded admission to segre

gated schools, the State Board was forced to answer that

such admission could not be granted by the State Board

alone.

On May 2, 1956, seven actions were filed in the Federal

District Court for the District of Delaware. In each action

Negro students who were residents of one of Delaware’s

segregated school districts, filed suit against the members

of the State Board of Education, the State Superintendent

of Public Instruction, and the members of the local school

district board for the district in which they lived. The

prayer for relief in each case was that the various rules,

regulations, laws, etc., by which segregation was maintained

be declared unconstitutional and that the Court issue an

injunction requiring the defendants to admit, on a racially

non-discriminatory basis, the plaintiffs and others similarly

7

situated to the school within the district of the defendant

local board.

In one of the present actions, defendant local board

members moved to dismiss as to them. In Brenda Evans

et al. v. Members of the State Board of Education, et al.,

145 F, Supp. 873 (D. C. D el, 1956), Judge Wright ruled

that the local board was properly a defendant in the action,

that the local boards are a legislative creation of the State

of Delaware, that the rules and regulations of the State

Board have the force and effect of law and that the State

Board had requested of local boards that they prepare a

plan of desegregation.

The other six local boards answered the complaints in

an essentially similar manner; in each case alleging over

crowding in the “ white” schools in the local district and

alleging that all communities in Delaware south of Dover

are substantially a single community; that they should be

integrated as a whole and that the local boards are not

competent to deal with the problem. In each case, the

plaintiffs moved to strike the “ single community” defense.

The matter was extensively briefed by the defendant local

boards and by the plaintiffs. The Court has not ruled on

this motion.

On January 21, 1957, the plaintiffs in one of the present

actions filed a motion for summary judgment against all of

the defendants. In Evans et al. v. State Board et ah, 149

F. Supp. 376 (D. C. D el, 1957), Chief Judge Leahy made

findings of fact that the State Board, immediately after the

First Brown decision, made regulations calling for desegre

gation plans from local boards and that the State Board

made several attempts to get these plans from the local

boards. The Court further found that the local board

refused to act, and that, even assuming the local board only

acts in an advisory capacity, nevertheless, since the State

Board has charged the local boards with the duty to submit

a plan, both boards are properly before the Court. The

Court proceeded to find that while the State Board was

attempting to secure desegregation, the local board was

making no prompt or reasonable start toward desegregation.

Judge Leahy noted the State Board’s suggestion that the

plan be submitted by the local board directly to the Court;

however, the Court ruled that such procedure did not seem

to be necessary at that time. The local board was ordered

to submit a plan of desegregation to the State Board within

30 days and the State Board to submit its plan to the Court

within 60 days.

Defendant Local Board of Clayton School District took

an appeal from this order. The appeal was never prose

cuted and on July 5, 1957, the record on appeal was re

turned to the District Court. The Clayton Board has not

complied with the order.

On June 25, 1957, plaintiffs in all actions moved to

consolidate the actions and moved for summary judgment

against the State Board of Education and the State Super

intendent of Public Instruction asking that these defend

ants be required to submit to the Court a plan of desegrega

tion providing for admittance of Negro students at the

beginning of the next school term in all public school dis

tricts of the State of Delaware which heretofore have not

admitted Negroes under plans of desegregation approved

by the State Board. No evidence was taken, nor were affi

davits filed. The Plaintiffs submitted briefs arguing that the

plaintiffs had been unable to get their rights to desegre

gated education from the local boards and noting generally

the refusal of the defendant local boards to cooperate with

the State Board. The State Board filed a brief urging that

9

no reason had been shown for varying the ruling previously

made by the Court that the local boards must submit plans

to the State Board.

On July 15, 1957, the Court issued a Memorandum and

Order, printed in Appendix, page 10a, reported in 152 F.

Supp. 886, making certain findings of fact and law and

ordering the State Board to restrain from refusing admission

of Negro plaintiffs and all other children similarly situated

to the public school in the named school districts, and

further, to submit to the Court within 60 days, a plan of

desegregation providing for the admittance for the Fall

term of 1957, of Negro students in all public school districts

which heretofore have not admitted Negroes under a plan

of desegregation approved by the State Board.

The Court then ruled that to further “ obtain and

effectuate” admittance to school in the seven named dis

tricts and “ defendant Members of the State Board of

Education, having general control and supervision of the

public schools of the State of Delaware and having the duty

to maintain a uniform, equal, and effective system of public

schools throughout the State of Delaware,” and the State

Superintendent are ordered to submit a plan for the “ ad

mittance, enrollment and education on a racially non-

discriminatory basis, for the Fall term of 1957” of all

segregated school districts in Delaware.

The State Board of Education and the State Super

intendent of Public Instruction took an appeal from this

order on August 7, 1957.

The opinion from the Third Circuit, by Chief Judge

Biggs, was delivered on May 28, 1958. Therein, it was ruled

that the rights of the respondents are paramount, that this

Court has ruled upon the rights of the Negro children, that

10

the State Board has the authority to adopt a plan of desegre

gation, and that the Court would not assume that the local

boards would not follow the plan.

The petitioners’ motion for reargument was denied on

June 20, 1958, and the mandate was sent to the lower court

on June 30, 1958.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W RIT

It seems beyond question that the local boards must be

a party to any suit to gain admission to a school in Delaware.

Such is the opinion of the District Court in the first of three

opinions concerning these cases, arising on a motion by one

of the Boards to dismiss as to it. Brenda Evans, et al., v.

State Board, 145 F. Supp. 873. Appendix la. Judge Wright

said:

“The local school boards are a legislative creation of

the State of Delaware. The State Board of Education

has determined as a matter of general policy (1) ‘that

any steps toward integration must be embodied in a

plan to be devised by the local board,’ and (2) ‘that

any such plan must be submitted to the State Board for

consideration and approval.’ Regulations of the State

Board of Education have the force and effect of law. A

plan of integration cannot be formulated by the defend

ants as individuals. Any action taken by the individual

defendants relative to the integration problems of Clay

ton School District No. 119 is possible only because by

virtue of State law they are the duly and legally con

stituted Board of Trustees of the Clayton School Dis

trict. Thus, the defendants’ alleged failure to formulate

a plan for integration must be considered to be done

under color of State law.” (Appendix, p. 5a)

On a motion for summary judgment against the local

and State boards, the District Court again ruled that, under

the Delaware law, the local board must submit a plan to the

11

State Board before the State Board would be required to

submit a plan to the Court. Brenda Evans, et al., v. State

Board, et al., 149 F. Supp. 376. Appendix, p. 6a. Judge

Leahy said:

“ [ 1 ] The Local Board answers on several grounds.

They contend they are improper parties to this action

since they are not vested with the power to make or

determine educational policy, but function only in ad

visory capacity, and this power can not be delegated by

the State Board or altered by orders originating therein.

However, the mere fact the Local Board is required

only to recommend educational policy does not make

the Local Board an improper party to this action. The

State Board having charged the Local Board with the

duty to submit a plan for desegregation, both boards

are now properly before the Court. (Appendix, p. 7a-

8a)

“ Summary judgment is granted and an order should be

submitted directing the Board of Trustees of the Clay

ton School District No. 119 to submit a plan for the in

tegration of the public school to the State Board of

Education, in accordance with their existing rules and

regulations. Such plan by the Local Board shall be sub

mitted to the State Board within a period of 30 days.

Within 60 days, the State Board of Education shall sub

mit its plan to the Court for further instructions.” (Ap

pendix, p. 9a).

The reason for these two opinions is found in the curi

ous nature of the Delaware school system. Administrative

and policy making is divided between the State and local

boards.

One of the areas in which decision making and the exe

cution of the decision is divided between local boards and

the State Board is necessarily the area presently in issue. The

Supreme Court of Delaware has given what must be con-

12

sidered the only authoritative statement as to the relation

ship between the State and local boards in Delaware.

This statement was made in Stiener v. Simmons, .......

Del-------- , 111 A. 2d 574 (1955), at page 582:

“ No attempt is made by the State Board to force im

mediate desegregation upon any local board. Joint ac

tion is required. The somewhat loosely-knit educational

system of the State, with administrative and policy

making powers divided between state and local authori

ties, and the system of elective local boards prevailing

in Kent and Sussex Counties (and in a few districts in

New Castle County), obviously make such joint action

advisable— if not, indeed, necessary.”

In the Stiener case, as in the very case now before the

Supreme Court, the question was not one of desegregation

but rather of how desegregation was to be administered un

der the Delaware school organization. It is this question

which the Delaware Supreme Court concluded could only

be answered by bringing before the Court both the State and

the local boards. The issue was not before the Delaware

Court precisely because only the local board had acted, and

the Delaware Court found that the action was invalid be

cause the local board had failed to submit its plan to the

State Board before proceeding to attempt to integrate schools

in Milford, Delaware. On this basis alone, the Delaware

Court ruled improper the action of the local board and, at

that point, proceeded to state that “ joint action” is cer

tainly advisable and very likely “necessary.”

It cannot be emphasized too strongly by the State

Board that the question now before the Court, the question

before the Court of Appeals below, and the question finally

decided by the District Court is not one of desegregation at

all. The entire record and history of this case, from its initia-

13

tion, indicates that the State Board at no time has questioned

the right of the Negro children to attend desegregated

schools. Only the local boards have actually fought the prin

ciples of desegregation. The State Board has sought only to

secure the assistance of the Court in requiring the local

boards to cooperate with it in securing desegregation to the

respondents in these cases. In seeking to do so, the State

Board has, at least at the beginning, been in agreement with

the respondents in these cases themselves who actually

joined the local boards and each member of the local boards

in these actions, and also in the District Court itself which

declines to strike the local boards from the action in the

first opinion in the District Court (Appendix, p. la) and,

in the second decision in the District Court, actually ordered

the local board to proceed to supply a plan of desegregation

to the State Board before the State Board would be required

to submit the plan to the District Court (Appendix, p. 6a).

The action of the District Court has the approval of the

Court of Appeals in the District Court’s first case (Appendix,

p. 15a) and the action of the District Court in the second

decision is neither approved nor disapproved by the Court

of Appeals. A reading of the third decision in the District

Court, Brenda Evans, et al., v. State Board, et al., 152 F.

Supp. 886, and the decision of the Court of Appeals for the

Third Circuit, Brenda Evans, et al., v. State Board, et ah,

------ F. 2 d ......., Appendix, p. 15a, indicates that it is not an

analysis of Delaware law concerning school organization

which impelled these courts to rest the burden solely upon

the State Board of Education; but rather, it is a determina

tion to get on with the job apparently regardless of whose

responsibility it would be found to be under a precise analy

sis of the State laws and Delaware case decisions. The third

opinion in the District Court even while ordering the State

14

Board to proceed above, observed that it was not solely the

responsibility of the State Board. Appendix, p. 11a.

It is submitted that it is of vital importance on a na

tional basis that the Supreme Court should determine at this

time whether the Federal Courts may, in order to expedite

the administration of the constitutional rights of Negro chil

dren, change the actual organization and hierarchy of

responsibility in a state school system in order to secure more

promptly those rights. It is readily agreed by the State Board

that, if the order of the Court of Appeals and the District

Court were carried out successfully, it would substantially

expedite the securing of the rights in question to the Negro

children. However, these cases do not involve a simple ques

tion of form alone, but rather a matter of vital importance

to the state of Delaware. The order of the Court in this case

is the first instance to the knowledge of the State Board in

which a State Board of Education alone has been directed

to act as opposed to a direction running to a local board of

education. Although the Circuit Court and the District Court

have spoken in terms of the “ paramount authority” of the

State Board, nevertheless, a reading of the statutes indicates

that actually the authority which the State Board may exer

cise over a recalcitrant local board is in fact illusory. The

members of the local board are elected by the residents of

the local board district and are controlled in no way by the

members of the State Board. The local boards can in the

future, as they have in the past, disregard, with impunity,

instructions from the State Board. The fact that the local

boards in question have refused or failed to submit plans of

desegregation to the State Board even under a court order

to do so (Appendix, p. 6a) conclusively proves this point.

The State Board is sincerely concerned about the welfare

of the school system of Delaware and is extremely appre-

15

hensive of the plan of relieving the members of local school

boards of any responsibility for the implementation of de

segregation. Sound sociological and practical considerations

demand that the local boards be not permitted to claim com

plete abnegation of responsibility for the plan of desegrega

tion put into effect in their districts.

It must be noted that the third opinion of the District

Court and the opinion of the Court of Appeals did not spe

cifically overrule, nor declare unconstitutional, any of the

statutes concerning the Delaware school system except that

part requiring segregation nor any Delaware cases concern

ing the organization of the Delaware school system. How

ever, such failure can only be noted as an attempt to avoid

the problem rather than to solve it. The highest court of Del

aware, the Delaware statutes and the first two opinions of

the District Court of Delaware correctly placed the local

boards precisely in the cases and equally responsible with

the State Board. It is submitted that the Supreme Court of

the United States should settle the question at this time

whether Federal courts, in order to expedite civil rights, may

even tacitly, as in this case, alter the organization of a school

system and shift responsibility from where it is placed by

State statute and judicial determination before such Federal

courts even attempt to use the existing administrative struc

ture of the State system.

CONCLUSION

It cannot be emphasized too strongly that the present

question is not one of desegregation. The State Board has

never raised that question and does not do so now. The

sole question is one of implementation of desegregation and

whether the Federal courts may alter the effect of state laws

16

of school administration and responsibility. It is submitted

that this question is of great significance at the present time

and will be increasingly so within the coming years. This

petition for certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Jo s e p h D o n a ld C r a v e n ,

Attorney General

F r a n k O ’D o n n e l l , Jr .,

Chief Deputy Attorney General

F. A l t o n T y b o u t ,

Deputy Attorney General

Opinion (November 9, 1956) la

OPINION OF JUDGE WRIGHT IN BRENDA EVANS,

ET AL. v . MEMBERS OF THE STATE BOARD OF

EDUCATION, STATE SUPERINTENDENT OF PUB

LIC INSTRUCTION, MEMBERS OF THE BOARD

OF TRUSTEES OF CLAYTON SCHOOL DISTRICT

NO. 119*

W righ t , District Judge.

This is a class suit brought pursuant to Rule 23(a) (3)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, 28 U. S. C.* 1 All

of the plaintiffs are among those classified as “ colored” ,

of Negro blood and ancestry, and are residents of Clayton,

Delaware. The defendants are the members o f the State

Board of Education, the Board of Trustees of Clayton

School District No. 119 and the State Superintendent of

Public Instruction.

The complaint alleges plaintiffs “ * * * by reason of

their residence, except for their race, color and ancestry,

would be acceptable by defendants for attendance at the

public school in Clayton School District No. 119.” 2 3 The

complaint further charges that in response to a petition

addressed to the defendants, as members of the Board of

Trustees of the Clayton School District No. 119, “ * * * to

take immediate steps to reorganize the public school * * *

on a racially nondiscriminatory basis and to eliminate racial

segregation in said school,” 8 said defendants officially

stated they had no plan for desegregation.4 The failure and

* Opinion handed down November 9, 1956 reported in 145 F. Supp. 873.

1. “ Rule 23. * * * (a ) Representation. If persons constituting a class are

so numerous as to make it impracticable to bring them all before the court, such

of them, one or more, as will fairly insure the adequate representation of all may,

on behalf of all, sue or be sued, when the character of the right sought to be

enforced for or against the class is

♦ * *

“ (3 ) several, and there is a common question of law or fact affecting the

several rights and a common relief is sought.”

2. Par. 3 of the Complaint.

3. Par. 5 of the Complaint.

4. Par. 6 of the Complaint

2a Opinion (November 9, 1956)

refusal of the Board of Trustees of the Clayton School Dis

trict to reorganize the public school of the school district

on a racially nondiscriminatory basis was called to the at

tention of the defendant members of the State Board of

Education, who were requested to immediately desegregate

the public school.5 6 On March 15, 1956 the defendant mem

bers of the State Board of Education, by official action,

unanimously refused to comply with, the plaintiffs ’ request

to desegregate said public school.6

Some of the defendants, namely, the members of the

Board of Trustees of Clayton School District No. 119, have

moved to dismiss the complaint as to them on the grounds,

(1) the complaint fails to state a claim against the defend

ants upon which relief can be granted, and (2) this court

lacks jurisdiction over the subject matter.

[1-3] The defendants urge the complaint fails to state

a claim upon which relief can be granted because there is

absent any allegation of the non-existence of administrative

impediments to full faith compliance with the constitutional

principles set forth by the Supreme Court in the two Brown

decisions.7 Omission of this allegation is fatal, according

to defendants, because they read the second Brown de

cision as conditioning the right of a Negro to attend a public

school without regard to racial considerations.

Defendants misapprehend the meaning of the two

Brown decisions. The first Brown decision supplied an

unqualified affirmative answer to the question of whether

“ segregation of children in public schools solely on the

basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other

‘ tangible’ factors may be equal, deprive the children of a

minority group of equal educational opportunities” .8 The

5. Par. 7 of the Complaint.

6. Par. 8 of the Complaint.

7. Brown v. Board qf Education of Topeka, 1954, 347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct.

686, 98 L. Ed. 873, hereinafter referred to as the first Brown case; Brown v.

Board of Education of Topeka, 1955, 349 U. S. 294, 75 S, Ct. 753, 99 L. Ed.

1083, hereinafter referred to as the second Brown decision.

8. 1954, 347 U. S. 483, at page 493, 74 S. Ct. at page 691.

Opinion (November 9, 1956) 3a

Supreme Court expressed its holding in the following

manner:

“ * * * we hold that the plaintiffs and others simi

larly situated for whom the actions have been brought

are, by reason of the segregation complained of, de

prived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed

by the Fourteenth Amendment.” 9

In the second Brown decision, the Supreme Court referred

to the first Brown case as a declaration of “ the funda

mental principle that racial discrimination in public educa

tion is unconstitutional” .10 After incorporating the opinion

in the first Brown decision by reference into the opinion of

the second Brown decision, the Supreme Court indicated

the subject matter of the second opinion was to determine

“ the manner in which the relief is to be accorded.” 11

Therefore, the second Brown decision cannot be construed

as conditioning the constitutional right set forth in the first

Brown case. Rather, the second Brown decision must be

read as establishing a standard as to what constitutes a

good faith implementation of the governing constitutional

principles set forth in the first Brown decision. Not only

do the constitutional principles set forth in the first Brown

decision remain unqualified, but, the defendants also have

the burden of advancing reasons justifying delay in carry

ing out the Supreme Court ruling.12 It would be illogical

9. Id., 347 U. S. at page 49S, 74 S. Ct. at page 692.

10. 1955, 349 U. S. 294, at page 298, 75 S. Ct. at page 755.

11. Ibid.

12. “* * * the [inferior] courts will require that the defendants make a

prompt and reasonable start toward full compliance with our May 17, 1954,

ruling. Once such a start has been made, the courts may find that additional

time is necessary to carry out the ruling in an effective manner. The burden

rests upon the defendants to establish that such time is necessary in the public

interest and is consistent with good faith compliance at the earliest practicable

date. T o that end, the courts may consider problems related to administration,

arising from the physical condition of the school plant, the school transportation

system, personnel, revision of school districts and attendance areas into compact

units to achieve a system of determining admission to the public schools on a

nonracial basis, and revision of local laws and regulations which may be neces

sary in solving the foregoing problems.” (Emphasis added.) Brown v. Board

of Education of Topeka, 1955, 349 U. S. 294, at pages 300-301, 75 S. Ct. 753,

at page 756, 99 L. Ed. 1083.

4a Opinion (November 9, 1956)

to hold plaintiffs ’ complaint must set forth facts which de

fendants will have the burden of proving,

[4, 5] The second objection of defendants goes to the

jurisdiction of this court over the subject matter of the com

plaint. Jurisdiction is founded upon 28 IT. S. C. §§1331

and 1343. 28 U. S. C. § 1331 provides:

‘ ‘ § 1331. Federal question; amount in controversy

“ The district courts shall have original jurisdic

tion of all civil actions wherein the matter in contro

versy exceeds the sum or value of $3,000, exclusive of

interest and costs, and arises under the Constitution,

laws or treaties of the United States. June 25, 1948,

c. 646, 62 Stat. 930.”

The pertinent portion of 28 U. S. 0. § 1343 provides:

‘ ‘ § 1343. Civil rights

“ The district courts shall have original jurisdic

tion of any civil action authorized by law to be com

menced by any person:

* # *

‘ '(3 ) To redress the deprivation, under color of

any State law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom

or usage, of any right, privilege or immunity secured

by the Constitution of the United States or by any Act

of Congress providing for equal rights of citizens or

of all persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States. June 25, 1948, c. 646, 62 Stat. 932.”

The jurisdiction of this court, invoked under the civil

rights jurisdictional statute, 28 U. S. C. § 1343, is questioned

by the defendants on the theory that when the Board of

Trustees of Clayton School District No. 119 officially stated

they had no plan for desegregation they were not acting

“ under color of any State law” . This conclusion is un

sound and can only be reached by traveling a tortuous path

of conceptualistie reasoning.

Opinion (November 9, 1956) 5a

The local school boards are a legislative creation of

the State of Delaware.13 The State Board of Education

has determined as a matter of general policy (1) “ that any

steps toward integration must be embodied in a plan to be

devised by the local board” , and (2), “ that any such plan

must be submitted to the State Board for consideration and

approval” .14 15 Regulations of the State Board of Education

have the force and effect of law.16 A plan of integration

cannot be formulated by the defendants as individuals.

Any action taken by the individual defendants relative to

the integration problems of Clayton School District No. 119

is possible only because by virtue of State law they are

the duly and legally constituted Board of Trustees of the

Clayton School District. Thus the defendants ’ alleged fail

ure to formulate a plan for integration must be considered

to be done under color of State law.1*

Since the court has jurisdiction under 28 U. S. C. § 1343,

it is unnecessary to determine whether the court would have

jurisdiction under 28 U. S. C. § 1331. Accordingly, that

question is left undecided. The defendants’ motion to dis

miss is denied.

An order in accordance herewith may be submitted.

13. 14 Del. C.

14. Steiner v. Simmons, Del. 19SS, 111 A. 2d 574, at page 582.

15. Id., I l l A. 2d at page 583.

16. Cf. E x parte Commonwealth of Virginia, 1879, 100 U. S. 339, at page

347, 25 L. Ed. 676: “Whoever, by virtue of public position under a State gov

ernment, deprives another of property, life, or liberty, without due process of

law, or denies or takes away the equal protection of the laws, violates the

constitutional inhibition; and as he acts in the name and for the State, and is

clothed with the State’s power, his act is that of the State.”

In lowa-Des Moines National Bank v. Bennett, 1931, 284 U. S. 239, at

page 246, 52 S. Ct. 133, at page 136, 76 L. Ed. 265, it was said: “ When a state

official, acting under color of state authority, invades, in the course of his duties,

a private right secured by the Federal Constitution, that right is violated, even

if the state officer not only exceeded his authority but disregarded special

commands of the state law.”

Finally, it has been stated, “ Misuse of power, possessed by virtue of state

law and made possible only because the wrongdoer is clothed with the authority

of state law, is action taken ‘under color of’ state law.” United States v.

Classic, 1941, 313 U. S. 299, at page 326, 61 S. Ct. 1031, at page 1043, 85

L. Ed. 1368.

6a Opinion (March 6, 1957)

OPINION OF JUDGE LEAHY IN BRENDA EVANS ET

AL., PLAINTIFFS, v. MEMBERS OF THE STATE

BOARD OF EDUCATION, STATE SUPERINTEND

ENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION, MEMBERS OF

THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF CLAYTON

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 119, DEFENDANTS.

Civ. A. No. 1816.

March 6, 1957.

L e a h y , Chief Judge.

This cause arises on plaintiffs’ motion for summary

judgment. A motion to dismiss was denied in D. C. Del.,

145 F. Supp. 873. The material facts essential to this mo

tion present no genuine issue. Plaintiffs are of Negro

ancestry, citizens of the United States and of the State of

Delaware, residing in the community known as Clayton, in

Kent County.1 Plaintiffs have not been accepted in the

public school under the jurisdiction of Clayton School Dis

trict No. 119,2 3 nor has the school district heretofore taken

as students persons of Negro ancestry.8 After the first

Brown decision by the Supreme Court on May 17, 1954,4 * the

State Board of Education adopted on June 11, 1954, certain

regulations calling on the local districts for proposed plans

for desegregation to be submitted for review. On August

19, 1954, and again on August 26, the State Board requested

all schools should present a tentative plan for desegregation

on or before October 1, 1954. On May 31, 1955, the Supreme

1. Complaint, par. 3 and Affidavits; Answer, Members of State Board of

Education hereinafter referred to as State Board and State Superintendent of

Public Instruction hereinafter referred to as State Superintendent, par. 3.

2. Complaint, par. 3 ; Answer, State Board and State Superintendent,

par. 3.

3. Complaint, par. 6 ; Answer, State Board and State Superintendent,

par. 6.

4. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686,

98 L. Ed. 873.

Opinion (March 6, 1957) 7a

Court came down with its second Brotmv decision.5 On

August 10, 1955, members of the Board of Trustees of

Clayton School District No. 119 were petitioned to take

immediate steps to eliminate racial segregation in its pub

lic school.6 By letter of February 10, 1956, the State Board

was apprised of the failure of the Clayton School to de

segregate and was requested to do so.7 The State Board,

by letter of March 16, 1956, made known it could not comply

with immediate desegregation absent joint action initiated

by the Local Board.8 9 The members of the Local Board

“ admit that they have as yet arrived at no plan for de

segregation of the Clayton School and that there is pro

posed no reorganization thereof.” 3

Plaintiffs ’ prayer for relief is in the alternative: 1. That

this Court issue interlocutory and permanent injunctions

ordering defendants to admit infant plaintiffs and all others

similarly situated to the public school in Clayton School

District No. 119 on a racially nondiscriminatory basis, or

2. That the Local Board be required to submit to the State

Board of Education a plan for integration of that sehool

providing for admittance not later than the school term be-

gining in September, 1957.

[1] The Local Board answers on several grounds.

They contend they are improper parties to this action since

they are not vested with the power to make or determine

educational policy, but function only in advisory capacity,

and this power can not be delegated by the State Board or

altered by orders originating therein. However, the mere

fact the Local Board is required only to recommend educa

tional policy does not make the Local Board an improper

5. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U, S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753,

99 L. Ed. 1083.

6. Complaint, par. 5 ; Answer, Board of Trustees of Clayton School District

No. 119 hereinafter referred to as Local Board, par. 5.

7. Complaint, par. 7 ; Answer, State Board and State Superintendent,

par. 7.

8. Complaint, par. 8 ; Answer, State Board and State Superintendent,

par. 8.

9. Complaint, par. 6 ; Answer, Local Board, par. 6.

8a Opinion (March 6, 1957)

party to this action. The State Board having charged the

Local Board with the duty to submit a plan for desegrega

tion, both boards are now properly before the Court.

[2] Defendant Local Board alleges “ that at no time

has a person of negro blood or ancestry been denied admis

sion to the Clayton School.” After the refusal of the Local

Board to grant the petition of plaintiffs requesting desegre

gation, it would be hollow formality to require them literally

to knock on the schoolhouse door.10

[3] The remainder of defendant Local Board’s con

tentions relate to the propriety of granting relief at this

time. The Local Board alleges if the relief requested by

plaintiffs is granted now, “ it will constitute a violation of

the mandate of the Supreme Court of the United States,

requiring the elapse of a reasonable time for the transition

of segregated schools to non-segregated schools.” It is fur

ther alleged the load of administrative work involved, the

lack of facilities or transportation, and the inadequacy of

personnel and school space prevents the Clayton School

from being presently operated on a non-segregated basis.

Finally, it is alleged the sudden change which would occur

in the present social make-up of the Clayton School Dis

trict would do great damage to eventual integration. But

matters of defense dealing with administrative problems

are, at this time, prematurely raised by the Local Board.11

The issue here is whether or not “ a prompt and reasonable

start toward full compliance” has been made. Despite the

fact that on May 17, on August 19, and on August 26, 1954,

10. See the opinion of Chief Judge Parker in Charlottesville School Board

v. Allen, 4 Cir., 240 F. 2d 59.

11. In the second Brozvn decision laying the blueprint for integration, the

Supreme Court indicated the procedure to be followed: “ * * * the [inferior]

courts will require that the defendants make a prompt and reasonable start

toward full compliance with our May 17, 1954, ruling. Once such a start has

been made, the courts may find that additional time is necessary to carry out

the ruling in an effective manner. The burden rests upon the defendants to

establish that such time, is necessary in the public interest and is consistent with

good faith compliance at the earliest practicable date.” (Emphasis mine.)

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, 300-301, 75 S. Ct. 753, 756.

Opinion (March 6, 1957) 9a

the State Board requested local boards to present plans

on or before October 1 of that year for the integration

of the public schools, no plan of any kind has been forth

coming by the Clayton School Board. And, although ex

pressions of community dissent may stay racial desegre

gation for a reasonable time in order to meet local problems

through good faith implementation, they can never become

an instrument to color interminably the governing con

stitutional principles as declared by the Supreme Court.

Here, there has been no prompt and reasonable start.

[4] The State Board of Education argues that if the

Clayton Board of Trustees is required to present a plan

for integration, it should be filed with this Court directly

and not with the State Board. It argues the prime re

sponsibility for formulating a plan belongs to the Local

Board, that since the rules of the State Board contemplate

voluntary submission of these plans, the effect of the pres

ent litigation is to hold the Local Board answerable to this

Court; and that otherwise the State Board would be placed

in a difficult and unsatisfactory position resulting in harm

both to it and the entire school system. The State Board

would thus be content to submit its views to this Court

when requested to do so. However, while the Board may

require the local boards to cope with local problems in the

first instance, it should not remove itself directly from the

scene because a litigant has sought the judicial arm to se

cure his rights. At this point in time, I see no reason for

not following the usual practice set out by the State Board

itself in its published rules and regulations.

Summary judgment is granted and an order should be

submitted directing the Board of Trustees of the Clayton

School District No. 119 to submit a plan for the integration

of the public school to the State Board of Education, in

accordance with their existing rules and regulations. Such

plan by the Local Board shall be submitted to the State

Board within a period of 30 days. Within 60 days, the

State Board of Education shall submit its plan to the Court

for further instructions.

10a Memorandum and Order

MEMORANDUM AND ORDER.

(Entered July 15, 1957.)

(In All Appeals.)

1. Among the several motions before the Court are

plaintiffs’ motion for consolidation of C. A. Nos. 1816

through 1822, inclusive under FR 42(a), and plaintiffs’

motion for summary judgment against the Members of

the State Board of Education and the State Superintendent

of Public Instruction under FR 56(a).

2. This Court disposed of a previous motion of plain

tiffs for summary judgment with respect to C. A. No. 1816/

as to which an appeal was taken to the Court of Appeals

for this Circuit but not legally prosecuted by the Local

Board, in accordance with law and the Rules of said Court

of Appeals. The time for filing a plan as to this particular

school district, as provided for in the order entered by

the Delaware District Court was continued, pending the

appeal, until further order of this Court. The present

order will be operative as to this Local Board for its failure

to perfect its appeal.

3. Answers of defendant State Board and State Super

intendent in all the Civil Actions pending are, in substance,

similar. I find as to plaintiffs and other Negro children

similarly situated, these answers acknowledge the existence

of racial segregation in the public schools of Delaware; 1 2

and this is a deprivation of rights guaranteed under the

1. See Evans, et al. v. Members of the State Board of Education, et at,

D. C. Del., 149 F. Supp. 376.

2. C. A. No. 1816: Complaint, pars. 3, 6, 7, 8 ; Answer, pars. 3, 6, 7, 8.

C. A. No. 1817: Complaint, pars. 8, 9, 10 ; Answer, pars. 8, 9, 10.

C. A. No. 1818: Complaint, pars. 3, 7, 8 ; Answer, pars. 3, 7, 8.

C. A. No. 1819: Complaint, pars. 3, 6, 7, 8 ; Answer, pars. 3, 6, 7, 8.

C. A. No. 1820: Complaint, pars. 3, 7, 8 ; Answer, pars. 3, 7, 8,

C. A. No. 1821: Complaint, pars. 3, 7, 8 ; Answer, pars. 3, 7, 8.

C. A. No. 1822: Complaint, pars. 3, 7, 8 ; Answer, pars. 3, 7, 8.

Memorandum and Order 11a

Federal Constitution and so declared inviolate by the

Supreme Court.8

4. The State Board of Education adopted in the sum

mer of 1954 regulations requiring the local school Boards

to submit to the State Board plans for racial desegregation

in the public schools. These regulations, especially as

they affected the local Boards, had binding force through

out the State of Delaware.3 4 This initiated a policy then

regarded feasible. But, it is also manifest the local Boards,

in Kent and Sussex Counties, in general, have not begun

to comply with these regulations. The regulations of the

State Board cannot be permitted to be wielded as an ad

ministrative weapon to produce interminable delay. In

the interplay of forces resulting in continuing violation of

plaintiffs’ constitutional rights, these rights of Negro chil

dren must retain their vitality. They are, indeed, para

mount.5 The State Board, though not solely responsible

for a solution of administrative procedures in this socio

logical-legal problem, must, in the final analysis, be held

answerable.

5. The State Board of Education, from its past per

formance, blandly asserts it must await initial local action

3. Brown, et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, et al., 347 U. S. 483,

349 U. S. 294.

4. 14 Del. Cde § 122; Steiner, et al. v. Simmons, et at, Del., I l l A . 2d 274,

580, 583 (per C. J. Southerland).

5. See Belton, et al. v. Gebhart, et al. and Bulah, et al. v. Gebhart, et al„

32 Del. Ch. 343, 87 A. 2d 862, aff’d in Del. Ch. 144, 91 A. 2d 137, cert, granted

in 344 U. S. 891, Misc. Order in 345 U. S. 972, aff’d in 347 U. S. 483, Misc.

Order in 348 U. S. 886, and aff’d and remanded in 349 U. S. 294.

A t 87 A . 2d 864-865:

“ Defendants say that the evidence shows that the State may not be

‘ready’ for non-segregated education, and that a social problem cannot be

solved with legal force. Assuming the validity of the contention without

for a minute conceding the sweeping factual assumption, nevertheless, the

contention does not answer the fact that the Negro’s mental health and

therefore, his educational opportunities are adversely affected by State-

imposed segregation in education. The application of Constitutional prin

ciples is often distasteful to some citizens, but this is one reason for Con

stitutional guarantees. The principles override transitory passions.”

12a Memorandum and Order

because the State Board “ is not and can not be as con

versant with local school problems as the local school

Boards.” The factual data contained in its Reports to

the Governor of the State of Delaware refutes this. This

Court readily understands the State Board, as to the prob

lem of integration, is not as conversant with local problems

as the local Boards, but the Court is in disagreement

whether the State Board cannot be, or, when measured

by its record of inaction in failing to negotiate a prompt

and reasonable start toward full compliance, it has tried

to be.

6. Clearly, it is best, in the abstract, to permit local

conditions to be handled in the first instance by Local

Boards for integration, as commanded by the Supreme

Court of the United States. But, it is also recognized

joint and not independent action is called for by all parties

concerned. The first mandate of the Supreme Court fixed

the law on this problem over three years ago, the second

mandate, over two years ago. Since that time no appre

ciable steps have been taken® in the State of Delaware to

effect full compliance with the law.

In conclusion, it is recognized, under the law as fixed

by the Supreme Court of the United States, the right of

plaintiffs to public education unmarred by racial segrega

tion is immutable; that each state faces problems indig

enous to its own circumstances; that circumstances in

Delaware require racial desegregation to become a reality

simultaneously throughout all communities; that the State

Board exercises general control and supervision over all

public schools in Delaware, including the Local Boards, and 6

6. The Delaware State Legislature has, by statute, provided the State

Board of Education with broad powers of general control and supervision,

including consultation with local Boards, Superintendents, and other officers,

teachers and interested citizens, determination of educational policies, appoint

ment of administrative assistants to administer its policies, requiring reports

from Local Boards, the decision of all controversies involving administration

of the school system, and the conducting of investigations relating to educational

needs and conditions. 14 Del. Code § 121,

Memorandum and Order 13a

has knowledge of the status of racial desegregation in those

schools; that the State Board’s admissions of continued

racial segregation in the public schools washes away all

dispute as to this issue, as raised by the Local Boards; and,

that any order by this Court directed to the State Board

is, a fortiori, directed to any Local Board over which it, in

turn, has authority.

It is hereby

Ordered and D ecreed by T his C ourt :

1. The motion of plaintiffs to consolidate the following

causes, C. A. 1816 through C. A. 1822, inclusive, be and the

same is hereby granted and all pending causes in this Court

are hereby consolidated for judicial decision.

2. The plaintiffs’ motions for summary judgment in

C. A. 1816 through C. A. 1822, inclusive, as against the

Members of the State Board of Education and the State

Superintendent of Public Instruction be and the same are

hereby granted.

3. The minor plaintiffs in the respective cases and all

other Negro children similarly situated are entitled to ad

mittance, enrollment and education, on a racially non-

discriminatory basis, in the public schools of Clayton

School District No. 119, Milford Special School District,

Greenwood School District No. 91, Milton School District

No. 8, Laurel Special School District, Seaford Special

School District and John M. Clayton School District No. 97,

respectively, no later than the beginning of or sometime

early in the Fall Term of 1957.

4. In accordance therewith defendants are permanently

enjoined and restrained from refusing admission, on ac

count of race, color or ancestry, of respective minor Negro

plaintiffs and all other children similarly situated to the

public schools maintained in the respective above-men

tioned school districts.

14a Memorandum and Order

5. To further obtain and effectuate admittance, enroll

ment and education of said minor plaintiffs and all other

children similarly situated to the public schools maintained

in the respective above-mentioned school districts, on a

racially nondiscriminatory basis, defendant Members of

the State Board of Education, having general control and

supervision of the public schools of the State of Delaware

and having the duty to maintain a uniform, equal and

effective system of public schools throughout the State of

Delaware, and defendant George R. Miller, Jr., State

Superintendent of Public Instruction, shall submit to this

Court within 60 days from the date of this order a plan

of desegregation providing for the admittance, enrollment

and education on a racially nondiscriminatory basis, for

the Fall Term of 1957, of pupils in all public school dis

tricts of the State of Delaware which heretofore have not

admitted pupils under a plan of desegregation approved by

the State Board of Education.

6. 15 days prior to the submission of said plan to this

Court, defendant Members of the State Board of Educa

tion, etc., shall send in writing by registered mail a copy of

the plan of desegregation herein ordered to be submitted to

this Court, together with a copy of this Order, to each

member of the school board in all public school districts

of the State of Delaware which heretofore have not ad

mitted pupils under a plan of desegregation.

(s ) P aul L eah y ,

Chief Judge.

At Wilmington,

July 15, 1957.

15a

OPINION OF CHIEF JUDGE BIGGS IN THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD

CIRCUIT IN BRENDA EVANS, ET AL. V. MEM

BERS OF THE STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION,

STATE SUPERINTENDENT, THE LOCAL BOARD

OF CLAYTON SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET AL.

Civ. Actions Nos. 12,375— 12,381

(Filed May 28, 1958)

By Biggs , Chief Judge.

The appeals at bar arise out of seven cases in the court

below relating to the same subject matter and may be dis

posed of appropriately in one opinion. The jurisdiction of

16a

the court below was invoked under Section 1331, federal

question and jurisdictional amount, under Section 1343,

Civil Rights, Title 28, U.S.C. and under Section 1983, Title

42, U.S.C., and under the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States. No issue as to jurisdic

tion is presented.

The histories of these litigations are set out in some

detail in the opinions of the court below, referred to from

time to time hereinafter, and need not be repeated here.1

It is sufficient to state that following the decisions of the

Supreme Court of the United States in Brown v. Board

of Education and Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) and 349 U.S.

294 (1955), the Delaware State Board of Education re

quested the local school district boards to submit plans for

the admission and education of Negro children into the pub

lic schools of the respective school districts on a racially

non-discriminatory basis. There was prompt compliance by

many school districts in Delaware but the local school dis

trict boards in Kent and Sussex Counties in general did not

comply with the directions of the State Board of Education.

Thereafter the minor plaintiffs, children residing within

seven school districts, by guardians ad litem, brought the

seven suits in the court below to compel compliance with the

rulings of the Supreme Court of the United States in the

Brown case.

All of the complaints allege that the minor plaintiffs

are children resident within their respective school board

districts and are entitled immediately to admission to the

schools of their districts and would be accepted as students

therein except for their race, color and ancestry. The seven

suits are class actions brought on behalf of all children

similarly situated to the minor plaintiffs, pursuant to Rule

23(a)(3) Fed. R. Civ. Proc., 28 U.S.C.2

1 See also the opinion of the Supreme Court of Delaware in Steiner v.

Simmons, — Del. —, i l l A . 2d 574 (1955).

2 “ Rule 2 3 . . . (a ) Representation. If persons constituting a class are

so numerous as to make it impracticable to bring them all before the court,

such of )hem, one or more, as will fairly insure the adequate representation of

17a

The defendants are members of the State Board of

Education, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction

and members of local school boards. The relief sought

by the complaints was that the court below grant inter

locutory and permanent injunctions declaring that the

administrative orders, regulations and rules, practices or

usages, pursuant to which the minor plaintiffs are segre

gated with respect to their schooling because of race, color

or ancestry, violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States, and that the court below

issue interlocutory and permanent injunctions requiring the

defendants to admit the minor plaintiffs and all other

children similarly situated to the public schools of their

respective school districts on a racially non-discriminatory

basis.

The appellants, who are members of the State Board

of Education and the State Superintendent of Public In

struction, tiled joint answers in all seven cases asserting

that the power to effect desegregation lies not in them

but in the local school boards. The members of the boards of

education of the school districts also filed joint answers.

These answers are substantially the same and, briefly put,

assert that the local boards do not possess the power or

jurisdiction under the school laws of Delaware, or the avail

able facilities, to effect the admission of the minor plaintiffs

or other children similarly situated to the respective schools

on a racially non-discriminatory basis.

The members of the Board of Trustees of Clayton

School District No. 119, at C.A. No. 1816 in the court below,

No. 12,375 in this court, answered also that they were

“ improper parties” to the action. The court below cor

rectly held this contention invalid. 149 F. Supp. 376

(D.C.Del. 1957). ____________________________________

all may, on behalf of all, sue or be sued, when the character of the right sought

to be enforced for or against the class is

“ (3 ) several, and there is a common question of law or fact affecting the

several rights and a common relief is sought.”

In respect to the right of the plaintiffs to maintain a class action, see I4S

F. Supp. 873 (D.C.Del. 1956).

18a

On January 21, 1957 the plaintiffs in the case involving

the Clayton School District mentioned immediately above

filed a motion for summary judgment pursuant to Rule

56(a), Fed. R. Civ. Proc., 28 U.S.C.3 After argument, the

court below on March 6, 1957, filed an opinion, 149 F. Supp.

376, holding that the members of the Board of Trustees of

Clayton School District No. 119 were making no reasonable

start toward the admissions of the minor plaintiffs and those

similarly situated on a racially non-discriminatory basis.

Following this opinion, on April 1, 1957, the court entered a

decree enjoining members of the Board of Trustees of the

Clayton School District ‘ ‘ in accordance with further order ’ ’

from refusing admission to children on account of race,

color or ancestry and requiring the members of the Board

of Trustees of the Clayton School District to submit to the

State Board of Education, within 30 days, a plan for the

admittance to, and the enrollment and education in the

public school maintained by the Board of the minor plain

tiffs and all other children on a racially non-discriminatory

basis, and also requiring the members of the State Board of

Education within 60 days to file a plan so providing with

the court below.

An appeal from this decree was taken to this court but

was not prosecuted and accordingly the record was returned

to the court below. The decree of April 1, 1957 is presently

outstanding. No other similar decree addressed to members

of the local school boards was entered in the other six cases

but it is in this respect only that the case involving Clayton

School District No. 119 differs in substance from the other

six cases involving the other local school boards. However,

in view of the fact that the operation of the decree in the

Clayton case was made contingent on a further order of the

3 Rule 56(a) is as follow s: “ For Claimant. A party seeking to recover

upon a claim, counterclaim, or cross-claim or to obtain a declaratory judgment

may, at any time after the expiration of 20 days from the commencement of

the action or after service of a motion for summary judgment by the adverse

party, move with or without supporting affidavits for a summary judgment in

his favor upon all or any part thereof.”

19a

court below we are justified in treating and will treat this

case as in pari passu with the other six cases.

On June 21, 1957, the plaintiffs in six of the seven

cases, the case at No. 1816 in the court below involving

Clayton School District No. 119 being excluded, moved for

summary judgment against the members of the State Board

of Education and the State Superintendent of Public In

struction. It should be noted that the defendants who are

members of the local school boards were not included in

these motions. On June 25, 1957, the plaintiffs in the six

cases last referred to, the case at No. 1816 in the court below

being excluded, moved to consolidate the six eases.

On July 25, 1957, the court below handed down an

opinion, 152 F. Supp. 886, granting the motion to consoli

date the six cases and the motions for summary judgment

against the members of the State Board of Education and

the State Superintendent of Public Instruction. The court

below went further, however, and, apparently sua sponte,

since no applicable like motions had been filed for summary

judgment and for consolidation in respect to the suit at No.

1816 in the court below involving the Clayton School Dis

trict No. 119, also granted summary judgment in that case

against the members of the State Board of Education and

the State Superintendent of Public Instruction and con

solidated that case with the other six actions. The decree

of the court below was an appropriate and proper one, and

furnishes us with an additional reason for treating the

appeal involving the Clayton School District No. 119 on a

parity with the other six cases. The decree entered in all

seven cases by the court below requires that the minor

plaintiffs in all seven cases and children similarly situated

should be admitted to their respective school districts on a

racially non-discriminatory basis by the Autumn term 1957

and enjoins the designated defendants from refusing admis

sion to these children. It also directs the State Board of

Education and the Superintendent of Public Instruction to

submit a plan to the court for the admittance, enrollment

20a

and education of the children on a racially non-discrimina-

tory basis within 60 days and to serve copies of the plan

upon the members of the local school boards involved within

45 days.4 The appeals at bar, taken by the members of the

State Board of Education and the Superintendent of Public

Instruction, followed.

The State Superintendent of Public Instruction and

the members of the State Board of Education assert that

the exercise of two powers are essential for planning and

4 The order of the court is as follow s:

“ 1. The motion of plaintiffs to consolidate the following causes, C. A.

1816 through C. A. 1822, inclusive, be and the same is hereby granted and

all pending causes in this Court are hereby consolidated for judicial decision.

“2. The plaintiffs’ motions for summary judgment in C. A. 1816 through

C. A. 1822, inclusive, as against the Members of the State Board of Educa

tion and the State Superintendent of Public Instruction be and the same

are hereby granted.

“3. The minor plaintiffs in the respective cases and all other Negro

children similarly situated are entitled to admittance, enrollment and educa

tion, on a racially nondiscriminatory basis, in the public schools of Clayton

School District No. 119, Milford Special School District, Greenwood

School District No. 91, Milton School District No. 8, Laurel Special

School District, Seaford Special School District and John M. Clayton

School District No. 97, respectively, no later than the beginning of or

sometime early in the Fall Term of 1957.

“4. In accordance therewith defendants are permanently enjoined and

restrained from refusing admission, on account of race, color or ancestry,

o f respective minor Negro plaintiffs and all other children similarly

situated to the public schools maintained in the respective above-mentioned

school districts.

_ “ 5. T o further obtain and effectuate admittance, enrollment and edu

cation of said minor plaintiffs and all other children similarly situated to

tlie public schools maintained in the respective above-mentioned school

districts, on a racially nondiscriminatory basis, defendant Members of the

State Board of Education, having general control and supervision of the

public schools of the State of Delaware and having the duty to maintain a

uniform, equal and effective system of public schools throughout the State

of Delaware, and defendant George R. Miller, Jr., State Superintendent

of Public Instruction, shall submit to this Court within 60 days from the

date of this order a plan of desegregation providing for the admittance,

enrollment and education on a racially nondiscriminatory basis, for the

Fall Term of 1957, of pupils in all public school districts of the State of

Delaware which heretofore have not admitted pupils under a plan of

desegregation approved by the State Board of Education.

“6. 15 days prior to the submission of said plan to this Court, defendant

Members of the State Board of Education, etc., shall send in writing by

registered mail a copy of the plan of desegregation herein ordered to be

submitted to this Court, together with a copy of this Order, to each member

of the school board in all public school districts of the State of Delaware

which heretofore have not admitted pupils under a plan of desegregation.”

21a

effecting desegregation. They argue that to admit the

children involved to the respective public schools involved,

authority must be exercised to admit individual students to

one school rather than to another and that to educate stu

dents it is necessary to possess the authority to employ and

assign teachers and principals to the various schools. They

assert also that the powers necessary to effect these results

are vested by the pertinent Delaware statutes solely in the

local district school boards. They point to the provisions

of 14 Del. C., Sections 741, 944, 976, 1401 and 1410, which

variously provide for the employment of teachers and prin

cipals of schools, for the fixing of their salaries and for the

termination of their employment.

The appellants point also to 14 Del. C., Sections 902

and 941, providing for the establishment of Boards of

Education in the local school districts 8 and specifying the

duties of these boards, included among which is the deter

mining of policies in relation to the maintaining of separate

schools for white and colored children, and the settling of

disputes and for properly administering the public schools

of the districts. The appellants also assert that they are

without the authority to impose a plan for desegregation on

the boards of education of the respective school districts

because the members of these boards in Kent and Sussex

Counties are elected by the voters of the school districts, 14

Del. C., Section 305, and that therefore they are without

authority to appoint or remove these elected representatives

or to control their actions in any way. In short, the appel

lants contend that they are without power effectively to

carry out the court’s decree.

Some of the local or district school boards, employing

those of Milford, Seaford, Laurel and Greenwood as ex

amples, contend primarily that the State Board of Educa

tion possesses the power to determine the operation of the

public schools and that the State Board has the authority to

5 It should be noted that Section 301, 14 Del. C., defines a “district” as

meaning a “ School District or a Special School District or both.”

22a

adopt rules and regulations for the administration of the

public school system of Delaware and that these shall be

binding throughout the State. 14 Del. C., Section 122.

They assert also that the school laws of Delaware put the

burden on the Board of Education and the State Superin

tendent of Public Instruction to maintain a “ uniform, equal

and effective” educational system in Delaware. 14 Del. C,,

Section 141. The plaintiffs make similar contentions but

they also assert that the Supreme Court of Delaware in

Steiner v. Simmons, — Del. —, 111 A. 2d 547 (1955), held

that the State Board of Education has the power to regulate

the public schools of Delaware, relying inter alia on 14

Del. C., Sections 101(a), 121 and 122. These statutory

provisions place certain supervisory powers over the whole

of the Delaware School system in the State Board of Educa

tion. While the parties to these suits make other and

further contentions these need not be discussed in this

opinion. It should be noted, however, that we have con

sidered them.

In determining the issues presented it is necessary to

start with the guiding principles enunciated by the Supreme

Court in its opinions in United States v. Board of Educa

tion of Topeka, supra. First, the Supreme Court has ruled

that the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States prohibits the segregation of children in

public schools solely on the basis of race. Second, the

Court has prohibited admission to the public schools on a

basis of racial discrimination. Third, the Court has re

quired United States District Courts to enter such decrees

as are necessary and proper to admit children to public

schools on a racially non-discriminatory basis “ with all

deliberate speed.”

Among the statutory duties entrusted to the State

Board of Education by the General Assembly of Delaware

is that of maintaining a “ uniform, equal and effective sys

tem of public schools throughout the State . . . ” , 14

Del. C., Section 141. "While this section of the Delaware

23a