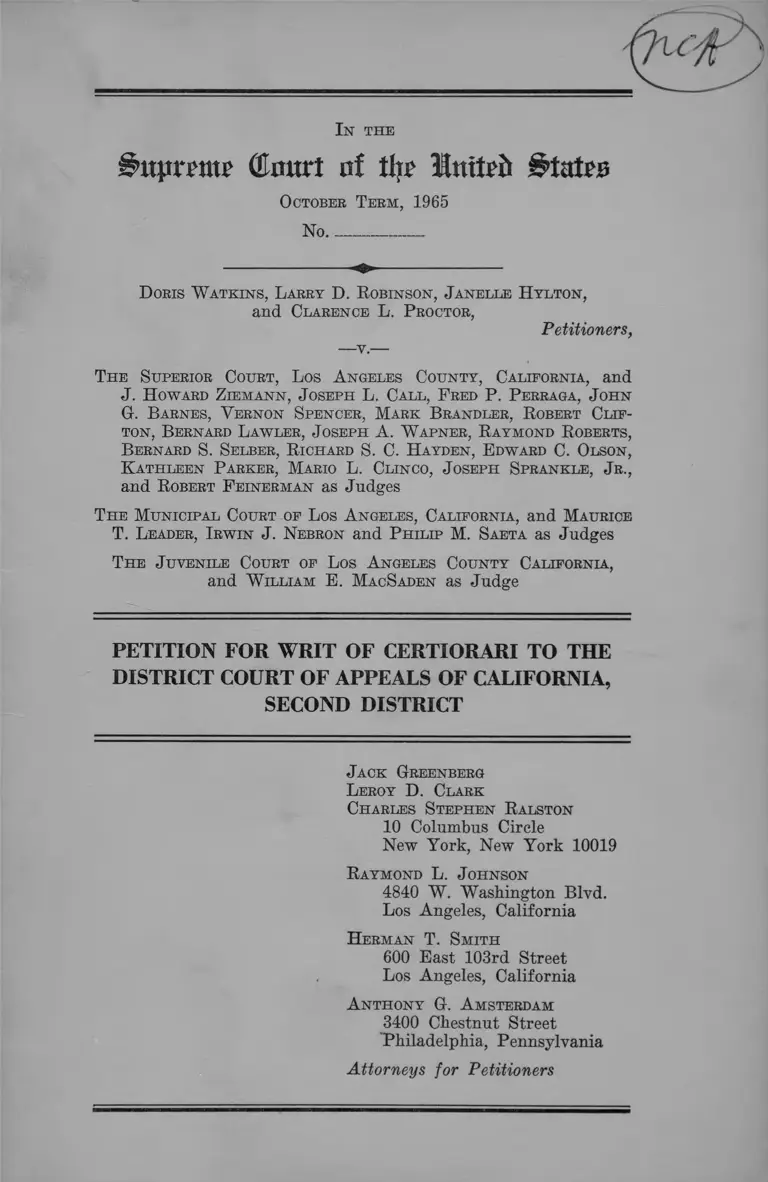

Watkins v. California Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Watkins v. California Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1965. e55765a9-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3c871111-faec-4dd7-b741-56e65214cb0e/watkins-v-california-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

In the

(Emtrt df % Unttrii States

October Term, 1965

No____________

D oris W atkins, Larry D. Robinson, Janelle H ylton,

and Clarence L. Proctor,

Petitioners,

— v .—

The Superior Court, Los A ngeles County, California, and

J. H oward Ziemann, Joseph L. Call, Fred P. Perraga, John

0 . Barnes, V ernon Spencer, Mark Brandler, Robert Clif

ton, Bernard Lawler, Joseph A. W apner, Raymond Roberts,

Bernard S. Selber, Richard S. C. Hayden, Edward C. Olson,

K athleen Parker, Mario L. Clinco, Joseph Sprankle, Jr.,

and Robert F einerman as Judges

The Municipal Court of Los A ngeles, California, and Maurice

T. Leader, Irwin J. Nebron and Philip M. Saeta as Judges

The Juvenile Court of Los A ngeles County California,

and W illiam E. MacSaden as Judge

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

DISTRICT COURT OF APPEALS OF CALIFORNIA,

SECOND DISTRICT

Jack Greenberg

Leroy D. Clark

Charles Stephen Ralston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Raymond L. Johnson

4840 W. Washington Blvd.

Los Angeles, California

H erman T. Smith

600 East 103rd Street

Los Angeles, California

A nthony G-. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Citations to Decisions Below ....................................... 1

Jurisdiction ......................................................................... 2

Question Presented ............................................................ 3

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved .... 4

Statement ............................................................................. 4

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

B elow ................................................................................. 10

Reasons for Granting the Writ ...................................... 11

Petitioners Adequately Alleged in Their Petition

for Writ of Prohibition and Mandamus Facts That

Establish That Their Continued Prosecutions Vio

late Their Right to Adequate Representation by

Counsel in Violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States....... 14

A. Under California Law, Petition for Writ

of Mandamus and Prohibition Is the

Proper Remedy ............................................ 14

B. The Allegations of the Petition for Pro

hibition and Mandamus Establish a Denial

of Due Process in Violation of the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States in That Petitioners

Have Been Denied Adequate Representa

tion by Counsel....................... ...................... 15

11

C. Petitioners Were Denied Due Process of

Law by the Failure of Respondents to Pro

vide for Counsel Immediately After Arrest 19

Conclusion .................................................................................... ....... 21

A ppendices :

A ppendix A —

Proceedings Below ............................................ la

A ppendix B—

California Statutes Involved...............................21a

T able of Cases

Badillo v. Superior Court, 46 Cal. 2d 269, 294 P. 2d 23

(1956) 14

Bogart v. Superior Court of Los Angeles County, 60

Cal. 2d 436, 34 Cal. Rptr. 850, 386 P. 2d 474 (1963) .... 14

Brubaker v. Dickson, 310 F. 2d 30 (9th Cir. 1962) ....... 18

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U. S. 129, 133 ....................... 15

Cornell v. Superior Court, 52 Cal. 2d 99, 102-03, 338

P. 2d 447, 449 (1959) .................................................... 18

De Rocke v. United States, 337 F. 2d 606 (9th Cir.

1964) ................................................................................. 18

Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U. S. 478 .................................. 19

Funk v. Superior Court, 52 Cal. 2d 423, 340 P. 2d 593

(1959)

PAGE

15

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U. S. 335 .......................16,18,19

Goforth v. United States, 314 F. 2d 868 (10th Cir.

1963) ................................................................................. 18

Hamilton v. Alabama, 368 U. S. 52 .............................. 19

Hammerstein v. Superior Court of California, 341 U. S.

491 ..................................................................................... 2

Harvey v. Mississippi, 340 F. 2d 263 (5th Cir. 1965) .... 16

Hawk v. Olson, 326 U. S. 271, 278 (1945) ....................... 17

Johnson v. United States, 328 F. 2d 605 (5th Cir. 1964) 17

Jones v. Cunningham, 313 F. 2d 347 (4th Cir. 1963) 17

Konisberg v. State Bar, 353 U. S. 252, 253-258 ........... 11

Lambert v. Municipal Court, 53 Cal. 2d 690, 3 Cal.

Rptr. 168, 349 P. 2d 984 (1960) .................................... 14

Pennsylvania ex rel. Herman v. Claudy, 350 U. S. 116 15

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45 (1932) ....................... 16

Powell v. Superior Court, 48 Cal. 2d 704, 312 P. 2d 698

(1957) ............................................................................... 15

Rescue Army v. Municipal Court, 28 Cal. 2d 460, 171

P. 2d 8 (1946) ................................................................. 14

Rescue Army v. Municipal Court of the City of Los

Angeles, 331 U. S. 549 .................................................. 2

Townsend v. Bomar, 331 F. 2d 19 (6th Cir. 1964) ....... 18

Turner v. Maryland, 318 F. 2d 852 (4th Cir. 1963) .... 18

Vance v. Superior Court, 51 Cal. 2d 92, 330 P. 2d 773

(1958) ............................................................................... 15

I l l

PAGE

Whitney v. Municipal Court, 58 Cal. 2d 907, 27 Cal.

Rptr. 16, 337 P. 2d 80 (1962) ...................................... 14

IV

S tatutes

California Code of Civil Procedure:

PAGE

§§1084, 1085 ..........................................................4,6,24a

§1086 ........................................................................... 4,25a

§1102 ........................................................................4,6,25a

§1103 ........................................................................... 4,25a

California Penal Code:

§858 ..........................................................................4,9,21a

§859 ..........................................................................4,9,21a

§859a ............................................................................4,22a

§987 ............................................................................. 4,23a

§987a ........................................................................4,9,23a

Other A uthorities

Boone, Prohibition: Use of The Writ of Restraint in

California, 15 Hastings L. J. 161, 162 (1963) ........... 6

Los Angeles: And Now What?, America, Vol. 113, No.

9, Aug. 28, 1965, p. 199 .................................................. 21

Mozer, There’s No Easy Place to Pin the Blame, Life,

Vol. 59, No. 9, Aug. 27, 1965, pp. 31-33....................... 21

No Panacea, The Christian Century, Vol. LXXXII,

No. 34, Aug. 25, 1965, pp. 1027, 1028 .......................... 21

Report of the Joint Committee on Legal Aid of the

Province of Ontario, pp. 101-109 (March, 1965) ..... 17

Silverstein, Defense of the Poor in Criminal Cases in

American State Courts, Vol. II, pp. 60, 75 (The

American Bar Foundation, 1965) .............................. 9,17

I n the

i ’lij.in'uu' (Emtrt of tin' Httiteii Stall's

O ctober T eem , 1965

No......................

D oris W a t k in s , et al.,

Petitioners,

T h e S uperior Court, L os A ngeles Co u n ty ,

California, et al.

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

DISTRICT COURT OF APPEALS OF CALIFORNIA,

SECOND DISTRICT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the California District Court of Appeals,

Second District, entered in the above-entitled case on Octo

ber 18,1965.

Citation to Decisions Below

The decisions of the California District Court of Appeals,

Second District, and of the Supreme Court of California

are not reported and are set forth in Appendix A infra,

pp. 15a and 20a.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the California District Court of Ap

peals, Second District, denying petitioners’ petition for

mandamus and prohibition without opinion was entered

on October 18, 1965. Petition for hearing to review the

decision of the Court of Appeals was filed in the Supreme

Court of California and was denied without opinion on No

vember 3,1965.

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to Title

28 U. S. C. Section 1257(3), petitioners having asserted

below, and asserting here, deprivation of rights, privileges,

and immunities secured by the Constitution of the United

States.

The denial of writs of mandamus and prohibition to re

strain a lower court proceeding was a final judgment of

the state court that can be reviewed by writ of certiorari.

See, Rescue Army v. Municipal Court of The City of Los

Angeles, 331 U. S. 549.

Since the granting of a petition for hearing to review

the lower court’s determination is a matter of discretion

with the Supreme Court of California, certiorari in this

Court lies to review the decision of the District Court of

Appeals. See, Hammer stein v. Superior Court of Califor

nia, 341U. S. 491.

3

Question Presented

Some 4,000 persons, including petitioners, were arrested

over a nine-day period in Los Angeles County in August,

1965; the great majority are unable to pay for counsel. Be-

spondent judges have in almost all instances appointed the

county public defender whose office consists of 108 attor

neys, one-half of whom regularly handle criminal cases.

The 4,000 new cases have in a short time been superimposed

on a yearly load of 10,000 cases. Different public defenders

have represented defendants at different stages of the pro

ceedings ; counsel have been able to consult with clients for

periods of only five to ten minutes before important pro

ceedings. Petitioners petitioned the Supreme Court of Cali

fornia and the District Court of Appeals of California for

writs of prohibition and mandamus on the grounds that

they were being denied the right to adequate representa

tion in violation of the due process and equal protection

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States; no responsive pleading has ever been

filed. The petitions were denied without hearing and with

out opinion.

On this record, did the California courts err in denying

writs of mandamus and prohibition that would:

(a) require the trial judges to appoint counsel, who stood

ready to accept appointment, other than the public de

fender, or otherwise assure adequate representation of the

members of petitioners’ class;

(b) require the appointment of counsel as soon after ar

rest as practicable and before initial arraignment?

4

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

This case involves also the following statutes of the

State of California: California Penal Code §§858, 859,

859a, 987, and 987a; California Code of Civil Procedure

§§1084-1086, 1102-1103. (The text of these sections is set

out in full in Appendix B infra.)

Statement

Between August 11 and August 20, 1965, rioting occurred

in the Watts area of Los Angeles County, California. Ap

proximately 4,000 persons, including named petitioners,

were arrested and charged with various felonies, misde

meanors, and juvenile offenses. Substantially all the per

sons arrested have had bail set in initial arraignments,

have had preliminary examinations completed, and have

been given a date for trial.

The named petitioners are:

(1) Doris Watkins, who was charged with burglary.

At arraignment she was unrepresented by counsel, and

bail was set at $4,900, which she was unable to meet. At

the preliminary hearing the court appointed a member of

the Los Angeles County Public Defender’s office; he talked

with her for only a brief period to get information relative

to a reduction in bail. The court found probable cause for

holding her for trial, and Mrs. Watkins was released un

der $250 bail. Later, the petitioner plead not guilty at a

hearing where she was represented by a different member

5

of the public defender’s office. Subsequently, petitioner had

a 25-minute interview with another attorney from the pub

lic defender’s office (R. pp. 13-14; Appendix A, pp. lla-12a).

(2) Larry D. Robinson was charged with disturbing the

peace. At arraignment, where petitioner was not repre

sented, he plead not guilty and bail was set at $1,000. Al

though petitioner informed the court he wished representa

tion by private counsel, the court urged him to accept the

public defender. Petitioner is not able to pay private

counsel (R. p. 16; Appendix A, p. 14a).

(3) Clarence Proctor was charged with burglary. He

could not meet bail of $4,750 and remained in jail from

August 14, 1965, until his trial on November 17, 1965. Peti

tioner was unrepresented at the hearing when bail was set.

At the preliminary hearing on August 20, 1965, the court

appointed the public defender. The attorney consulted with

petitioner for approximately two minutes concerning the

circumstances of his arrest. Bail was reduced to $2,500,

which petitioner was also unable to meet. Despite peti

tioner’s letters to the public defender’s office requesting

consultation, no one from the office interviewed him until

October 3, 1965. At that time a member of the office told

petitioner that he had been very busy; they consulted for

about five or six minutes (R. pp. 14-16; Appendix A, pp.

12a-14a).

(4) Janelle Hylton was arrested and charged with

burglary. At arraignment on August 19, 1965, she was un

represented by counsel and bail was set at $4,500, which

petitioner was unable to meet. At the preliminary hearing

on August 24, the public defender was appointed and he

interviewed petitioner for approximately five minutes. The

6

court bound her over for trial and she was released on her

own recognizance. Up to the time of the filing of this suit,

petitioner had had two other brief interviews with different

members of the public defender’s office at her two appear

ances to enter a plea (R. pp. 12-13; App. A, pp. lOa-lla).1

On October 8, 1965, pursuant to Sections 1085ff. and

1102ff. of the California Code of Civil Procedure, petition

ers filed on behalf of themselves, and all others arrested

and charged with crimes arising out of the riots, a petition

1 While the following information was not before the California

courts and, therefore, not in the record, petitioners bring to the

Court’s attention the following proceedings, which are a matter

o f public record, hut occurred subsequent to filing the petition:

Petitioners Watkins and Proctor were tried and convicted of

trespass after the denial of relief in the California courts, on No

vember 9 and 17, respectively. Proctor was sentenced to five days’

imprisonment; a hearing for probation and sentencing of peti

tioner Watkins is set for December 3, 1965. Both petitioners were

represented by the public defender. These proceedings do not, of

course, moot the individual or representative claims of the peti

tioners. As to petitioner Watkins, since the trial court has not

finally disposed of her case under California law a court, by writ

o f prohibition, may void her conviction in order to afford complete

relief. See, Boone, Prohibition: Use of The Writ of Restraint in

California, 15 Hastings L. J. 161, 162 and cases cited therein. At

the time of filing, the petitioners proceeded as representatives of

o f a class of untried defendants, many of whom have not yet been

tried. Unavailability of adequate representation for all 4,000 de

fendants was the occasion for the filing of this proceeding for

prerogative w rits: the same unavailability of counsel required pro

ceeding in representative form ; if the State of California, by its

unilateral decision to try the individual petitioners can defeat this

class action, there is no way in which the fundamental constitu

tional claims of this large class of persons can be protected.

Petitioners Hylton and Robinson were represented by private

counsel secured by the Los Angeles NAACP chapter subsequent to

the filing of this action. They were tried on November 10th and

22nd, 1965, respectively, and both were acquitted.

7

for a writ of prohibition and mandamus in the Supreme

Court of California (R. pp. 1-19; App. A, pp. la-14a). No

responsive pleading was filed. The Supreme Court, on its

own motion, referred the petition to the California District

Court of Appeals, Second District, for determination. The

petition claimed that petitioners’ right to adequate repre

sentation by counsel, guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States, was being

abridged, and asked the Court to require respondent judges

to:

(1) Appoint counsel with adequate preparation, in

vestigation and counseling before conducting any

further proceedings;

(2) Nullify any prior proceedings in which Petitioners

or members of their class, after securing adequate

counsel, can demonstrate they were prejudiced by the

lack of counsel;

(3) Furnish the members of Petitioners’ class with

lists of private counsel, if the Public Defender’s Office

is found to have an inordinate case load, and to pro

vide compensation for such counsel as are chosen by

the indigent defendants (R. p. 9; App. A, p. 7a).

Although no responsive pleadings was filed, the district

court denied the petition without a hearing and without

opinion on October 18, 1965 (R. p. 20; App. A, p. 15a).

Subsequently, on October 25, 1965, petitioners filed in

the Supreme Court of California their petition for hearing,

pursuant to Rule 28 of that court. The petition sought to

transfer the cause to that court to review the denial of the

petition for prohibition and mandamus and raised the same

8

federal constitutional claims urged below (App. A, pp. 16a-

19a). In addition, petitioners moved for a temporary re

straining order restraining the respondents from conduct

ing any further criminal trials or juvenile proceedings

affecting members of petitioners’ class pending disposition

of the petition for hearing. Again, no responsive pleading

was filed.

On November 3, 1965, the Supreme Court of California

denied the petition for hearing summarily, without opinion

(App. A, p. 20a). Again, petitioners were not given the

opportunity to present proof of their allegations. Since

there were neither responsive pleadings filed nor evidence

taken, the allegations concerning the individual petitioners

must be taken as true. The following allegations relating

to the class of 4,000 defendants which the individual peti

tioners represent are also undenied and similarly must be

taken as true.

Petitioners are unable to pay for the services of private

counsel. Of the 4,000 persons arrested and charged with

various felonies and misdemeanors, virtually all are simi

larly indigent and unable to pay for counsel of their choice

(R. pp. 7-8; App. A, pp. 5a-6a). Moreover, at the time of

the bringing of this action, there were more than 700 de

fendants still in jail because they could not make bail.

Pursuant to California procedure, the individual respon

dents are the twenty-three judges conducting the pre-trial

and trial phases of the prosecutions of petitioners and other

members of their class, i.e., persons arrested during the

riots. They are charged under California law to satisfy

the requirement imposed by the Fourteenth Amendment

to the United States Constitution that all persons charged

9

with criminal violations, regardless of financial ability, be

afforded adequate representation by counsel.2 They have

purported to discharge their duty by appointing the Los

Angeles County Public Defender’s Office to represent all

but a few of the indigent defendants who appear without

counsel (R. pp. 5-6; App. A, p. 4a).

The Los Angeles County Public Defender’s Office con

sists of approximately 108 lawyers,3 of whom about one-

half are assigned to handle criminal cases at the pre-trial

and trial stages. On the average, the case load of the Of

fice has been 10,000 cases per year. Thus, the Office has

been charged with defending 4,000 additional cases within

a brief period of time without the expansion of its legal

and investigative staff that would be required to deal with

such an unprecedented load (R. pp. 5-6; App. A, pp. 4a,

18a).

The prosecutions of the persons arrested have been pro

ceeding rapidly (R. pp. 7-8; App. A, p. 6a). Since the end

of August, 1965, virtually all the defendants have been

arraigned, have had pre-trial hearings, and have had trial

dates set. Largely because of the lack of adequate legal

advice immediately after arrest, bail at two or three times

2 Calif. Penal Code, §§858, 859, 987a. See Appendix B, infra.

3 According to the official report of the Public Defender’s Office

for 1964, there were 66 lawyers in the office. (See Silverstein, De

fense of the Poor in Criminal Cases in American State Courts,

Vol. II, p. 60 (American Bar Foundation, 1965).) The figure of

108 includes, according to information obtained by petitioners’

counsel, those hired since the beginning of 1965. Of course, a hear

ing at which evidence could be developed would present a factually

correct record.

1 0

the normal amount was set by some of the respondent

judges in many instances (R. p. 4; App. A, p. 3a).4

As a result of the large additional number of defendants,

the Public Defender’s Office has been unable to provide

adequate counsel to those it represents. For many defen

dants, a different public defender has appeared at each

stage of the pre-trial proceedings (R. p. 5; App. A, p. 4a).

In many instances, the various public defenders assigned

indigents have consulted with defendants only five to ten

minutes before they were to appear at a preliminary hear

ing (R. pp. 5, 12, 15; App. A, pp. 4a, 10a, 13a). Although

many defendants have asked that private counsel be as

signed and compensated by the court, and such private

counsel were available for court-appointment through lists

furnished by bar associations and the Los Angeles Chapter

of the NAACP, the respondent judges have refused to ap

point private counsel in sufficient numbers to relieve the

public defender’s office (R. pp. 6, 16; App. A, pp. 4a-5a,

14a).

How the Federal Questions Were

Raised and Decided Below

In their petition for writs of mandamus and prohibition,

petitioners alleged that unless the relief sought was granted

they would continue to suffer the denial of their rights

under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States and the Constitution of California. It

4 In addition, members of the class are being tried daily, with

the four original petitioners herein having been tried already. On

the basis of information they have received, counsel for petitioners

estimates that about two-thirds of those arrested and who have not

plead guilty have been tried, and all will be tried in the next one

to two months.

1 1

was claimed that their continued prosecutions under the

circumstances alleged in their petition would result in the

effective denial of their right to adequate representation

by counsel guaranteed by the due process and equal pro

tection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. Also, it was

alleged that the respondents had no other adequate remedy,

since a lack of proper legal counsel would render it im

possible for the petitioners and the members of their class

to preserve their constitutional claims and to perfect ap

peals to raise these issues. These same claims were made

in the petition for hearing filed in the Supreme Court of

California.

Since, as will be shown below, there exists no adequate

state ground for the decision of the court below, it must be

deemed that it rested on a decision on petitioners’ federal

claims. See, Konigsberg v. State Bar, 353 U. S. 252, 253-

258.

Reasons for Granting the Writ

This petition, the allegations of which have never been

denied, presents important questions concerning the obli

gation of a state to provide adequate counsel for indigent

defendants. The prosecutions involved herein arose out of

rioting which broke out in the Watts area of Los Angeles

and which continued for a number of days last summer.

The riots—which this petition certainly does not attempt

to justify—occurred because of the continued injustices that

the poor believe are inflicted on them by an indifferent,

affluent society.

In the way it is conducting these prosecutions, the State

of California is merely perpetuating the same injustices

which gave rise to the disturbances. It is trying thousands

1 2

of indigents in a rapid, routinized manner which fails to

ensure that every individual will have at least the protec

tion of counsel who is able to devote the time required to

consult with his client fully and to prepare adequately his

defense. To these defendants justice can appear only as

an impersonal machine, a mere tool of the same powers in

society that have put them and kept them in their position

of poverty.

In this case petitioners are attempting, by a procedure

clearly appropriate under California law (see infra), to

correct this situation and gain for all those arrested in

Watts proper representation by counsel. The present pro

ceeding is the only way that the rights of the Watts de

fendants can be adequately vindicated. Day by day, de

fendants are being held in default of exorbitant bail, are

being tried without adequate preparation of their cases

and, perhaps most important, are being forced by all of

the pressures of their situation, including lack of needed

legal advice, to plead guilty to the charges against them.

If relief is not given here, there exists no procedure by

which the constitutional claims of so large a number of

defendants can, with any fair assurance, be presented to

any court for hearing. They must have adequate counsel

now to advise them concerning their pleas, to ensure that

all constitutional defenses will be raised and preserved and

to enable them to perfect appeals.

However, the State of California has conspicuously

ignored the serious issues raised by this action. Neither

the respondent judges nor the State have tiled responsive

papers. Petitioners have been denied in both the District

Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court of California all

opportunity for hearing, at which they may offer proof

13

and argue the validity of their constitutional claims. Their

petitions have been denied summarily without opinion with

the result that petitioners have not been given a hint of the

basis for denial.

The very manner in which the State of California has

thus callously disposed of the present case reinforces the

denials of federal constitutional rights of the petitioners

in their criminal prosecutions and makes it imperative that

this Court accept jurisdiction to affirm the obligation of

the State for fundamental fairness and civilized procedure

in all criminal proceedings, regardless of the indigency of

the defendants or the abhorrence to the community of the

offenses with which they are charged. Justice consistent

with due process and equal protection of the law cannot

be done, nor the confidence in law essential to its mainte

nance be preserved, by the careless and mechanical proc

essing, indifferent to fundamental constitutional guaran

tees, which California has given and is giving these serious

criminal prosecutions.

14

I.

Petitioners Adequately Alleged in Their Petition for

Writ of Prohibition and Mandamus Facts That Establish

That Their Continued Prosecutions Violate Their Right

to Adequate Representation by Counsel in Violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

A. Under California Law, Petition for Writ of Mandamus

and Prohibition Is the Proper Remedy.

California law makes clear that the writ of prohibition

and mandamns was the proper remedy if petitioners’ fed

eral constitutional claims are sustainable.

In a case closely analogous to this, the Supreme Court

of California was petitioned for a writ of mandamus, and

the court issued its writ of prohibition to halt a criminal

trial until the petitioner had been properly informed of

his right to counsel. Bogart v. Superior Court of Los An

geles County, 60 Cal. 2d 436, 34 Cal. Rptr. 850, 386 P. 2d

474 (1963).

Prohibition has issued to stop a criminal proceeding

where the defendant was held to answer solely on illegally

obtained evidence (Badillo v. Superior Court, 46 Cal. 2d

269, 294 P. 2d 23 (1956)); and where the prosecution was

being carried out under a statute or ordinance claimed to

be unconstitutional or otherwise invalid or inoperative

('Whitney v. Municipal Court, 58 Cal. 2d 907, 27 Cal. Rptr.

16, 377 P. 2d 80 (1962); Lambert v. Municipal Court, 53

Cal. 2d 690, 3 Cal. Rptr. 168, 349 P. 2d 984 (1960); Rescue

Army v. Municipal Court, 28 Cal. 2d 460, 171 P. 2d 8

(1946).) And similarly pre-trial mandamus has been used

to review discovery orders of trial courts in criminal cases.

15

Powell v. Superior Court, 48 Cal. 2d 704, 312 P. 2d 698

(1957); Vance v. Superior Court, 51 Cal. 2d 92, 330 P. 2d

773 (1958); Funk v. Superior Court, 52 Cal. 2d 423, 340

P. 2d 593 (1959).

B. The Allegations of the Petitioner for Prohibition and

Mandamus Establish a Denial of Due Process in Vio

lation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States in That Petitioners Have

Been Denied Adequate Representation by Counsel.

Since there were no responsive pleadings filed, no hear

ing afforded, no opportunity offered to develop facts by

use of compulsory process, and no findings of fact made

by either of the state courts below, the facts alleged in the

petitions filed in the lower courts must be taken as true.

Therefore, the only issue presented here is whether the

allegations of petitioners are sufficient to establish a denial

of petitioners’ right to adequate representation by counsel.

See, Pennsylvania ex rel. Herman v. Claudy, 350 U. S. 116 ;

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U. S. 129,133.

Briefly summarized, the petition in the California courts

alleged that petitioners and members of their class were,

because of their indigency, being forced through the mills

of justice in rapid order while being denied adequate coun

sel by the actions of the respondent courts and judges.

Four thousand indigent persons were arrested in a period

of nine to ten days (R. pp. 2, 5; App. A, pp. 2a, 4a). They

were assigned the public defender as counsel, despite the

fact that this resulted in a 40% increase in that office’s an

nual case load over a span of two weeks. Numerous defen

dants requested that private counsel be appointed and com

pensated by the court (R. pp. 5-6; App. A, pp. 4a-5a). In

spite of the enormous burden on the public defender, and

16

in spite of there being many private attorneys willing to

accept appointments if compensated, the judges have re

fused these requests (Ibid.). The result has been that, typi

cally, defendants have had only hurried consultations with

public defenders prior to their proceedings (E. p. 5; App.

A, p. 4a).

The right to counsel is a requirement of due process of

law under the Fourteenth Amendment. The right does not

depend on the defendant’s ability to pay for counsel, and

where the defendant is indigent the court must furnish an

attorney in all cases, felonies as well as misdemeanors.

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U. S. 335; Harvey v. Mississippi,

340 F. 2d 263 (5th Cir. 1965).

In the present case, of course, counsel has been furnished

in the form of the public defender. However, the right to

counsel established by the Fourteenth Amendment is the

right to adequate representation. Powell v. Alabama, 287

U. S. 45 (1932). The analogy between Powell and the pres

ent case is extremely close in that there the trial court

appointed “ all the members of the bar” (287 U. S. at 53)

to represent the defendants. It was not until the day of

trial that a particular lawyer was assigned the respon

sibility of conducting the defense. Thus, there was not

enough time for counsel to give the attention and prepara

tion necessary for an adequate defense. In the present case

as well, it is petitioners’ contention that the counsel could

not possibly be deemed adequate.

Here, the issue presented by the facts is clear; whether

50 to 60 attorneys can adequately represent 4,000 defen

dants in a period of five months through the whole criminal

pre-trial and trial process, including arraignments, prelimi

nary hearings, preparation for trials and the trials them

17

selves while those lawyers have obligations which other

wise fully occupy them. In a report issued by the American

Bar Foundation in July, 1965, the Los Angeles public

defender, “ indicated that though in general he had adequate

funds to run his office, he could use several additional

deputies and more administrative personnel.” Silverstein,

Defense of the Poor in Criminal Cases in American State

Courts, Vol. II, p. 75 (American Bar Foundation, 1965).

This statement was made, of course, prior to the riots and

arrests which led to a 40% increase in the office’s case

load. The uncontradicted allegations of the petitions are

that the lawyers in the public defender’s office have not

been able to spend the time with petitioners and the other

members of their class that would be necessary to ade

quately prepare defenses against the serious charges in

volved.5 6

As this Court has said, “ The defendant needs counsel

and counsel needs time.” Hawk v. Olson, 326 U. S. 271, 278

(1945). Many courts have recognized that adequate rep

resentation is possible only when counsel is able to and

does, in fact, spend sufficient time consulting with his client,

investigating the circumstances of the case, and preparing

for trial. See, e.g., Jones v. Cunningham, 313 F. 2d 347

(4th Cir. 1963); Johnson v. United States, 328 F. 2d 605

5 Petitioners do not intend any criticism of the Los Angeles Pub

lic Defender’s Office or of the public defender system in general.

In the normal situation it may be adequate. Under circumstances

such as obtained here, however, the office is simply not capable,

because of a shortage in manpower, to handle the situation. For

a comprehensive report and recommendations on various means of

providing representation for the poor, including an analysis of

the relative merits of public defender systems, see Report of the

Joint Committee on Legal Aid of the Province of Ontario (March,

1965), generally, and particularly at pp. 101-109.

18

(5th Cir. 1964); Townsend v. Bomar, 331 F. 2d 19 (6th

Cir. 1964); Brubaker v. Dickson, 310 F. 2d 30 (9th Cir.

1962); De Rocke v. United States, 337 F. 2d 606 (9th Cir.

1964); Turner v. Maryland, 318 F. 2d 852 (4th Cir. 1963);

Goforth v. United States, 314 F. 2d 868 (10th Cir. 1963).

And in Cornell v. Superior Court, 52 Cal. 2d 99, 102-03, 338

P. 2d 447, 449 (1959), the California Supreme Court said:

If the attorney is not given a reasonable opportunity

to ascertain the facts surrounding the charged crime

so that he can prepare the proper defense, the ac

cused’s basic right to effective representation would

be denied.

Thus, this case presents the important issue of not merely

the right of an indigent defendant to counsel, but the obli

gation of state courts to ensure that the appointed counsel

is able to do an adequate job of representation. That is,

when the circumstances are such that a public defender’s

office, or other source of free legal aid, cannot provide

adequate counsel, must the court appoint private attorneys

with compensation or employ some other means to ensure

adequate representation? Surely, Gideon requires that the

substance and not merely the form of representation of

indigents be assured. Therefore, that case means that

state court judges must consider the actual circumstances

surrounding the prosecution of indigents and to consider

and utilize alternative methods of providing counsel where

such action is necessary.

19

C. Petitioners Were Denied Due Process of Law by

the Failure of Respondents to Provide for Counsel

Immediately After Arrest.

In addition, this case raises the question of the obliga

tion of state courts to provide indigents with counsel im

mediately or as soon after arrest as practicable and before

any proceeding at which their rights might be affected.

The right to counsel is the right to be represented at

every stage of the proceeding at which the rights of a de

fendant may be affected. Hamilton v. Alabama, 368 U. S.

52. Moreover, Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U. S. 478, estab

lishes the importance of the right in the period between ar

rest and arraignment.

Since Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U. S. 335, establishes

that the right to counsel cannot depend upon the ability

of an accused to pay, it follows that an indigent must be

afforded the same protection as one who has retained his

own lawyer at all stages of the criminal process. There

fore, the state had an obligation to provide counsel after

arrest and prior to the initial arraignment.

The experience of petitioner Proctor provides vivid

proof of the necessity of such a rule. Proctor was arrested

on August 14, 1965. He was arraigned four days later on

August 18th. During the period between arrest and ar

raignment he saw no attorney and the arresting authori

ties made no effort to secure him legal aid. At arraignment

he was unrepresented by counsel; no inquiry was made by

the judge as to any prior convictions or present employ

ment. Thus, bail was set at $4,950, which Proctor was un

able to make. On August 20, 1965, a preliminary hearing

was held. The public defender was appointed as counsel

and had only a two-minute consultation with Proctor. Prob

2 0

able cause to bold bim for trial was found and bail was set

at $2,500; again, he was unable to make this amount (R.

pp. 14-16; App. A, pp. 12a-14a).

Proctor remained in jail for three months awaiting trial;

he wrote many letters to the public defender asking for

interviews, but was unsuccessful until October 3rd, when

he had a six-minute interview with a lawyer from that

office (R. p. 4; App. A, p. 13a). Finally, he was tried on

November 17, 1965, found guilty of trespass and sentenced

to five days in the county jail.

The case of this petitioner is not unique; he represents

the class of more than 700 other persons in jail when this

action was tiled because they could not make bail. If coun

sel had been provided for them prior to arraignment, a

proper amount of bail might have been set. These de

fendants require adequate counsel now to secure reductions

in bail and to ensure that their pre-trial constitutional

rights will not be lost.6

6 The more than 500 juvenile offenders arrested also suffered

from not having adequate counsel. According to a report issued

by the Los Angeles County Probation Department in November,

1965, the Los Angeles County Juvenile Court considered 534 ju

venile detention matters in two days. A t least 382 were ordered

detained with most being released before or at the disposition hear

ings held during the week of September 13, 1965. As of October

25, 1965, there were some juveniles still being held. The report

does not indicate whether any juveniles were released on hail or

were provided legal counsel. Biot Participant Study: Juvenile

Offenders, Research Report No. 26, Los Angeles County Probation

Department, November 1965, p. 31.

2 1

CONCLUSION

This action presents more than the question of the rights

of the individual petitioners, important as those rights may

be. It presents a crucial element of the relation between

the state and those who because of poverty and neglect

have been excluded from society, who have despaired of

proceeding through lawful process, but who have now be

come caught up in the machinery of the law, the enforcer

of the standards of that society. One commentator said,

after the riots in Watts had ended:

Politicians, psychologists, educators, civil rights lead

ers and hosts of others joined the sociologists in

pondering the causes. They nearly all came up with

the same answer: the frustration and utter hopeless

ness of the ghetto-locked Negro. Mozer, “ There’s No

Easy Place to Pin the Blame,” Life, vol. 59, No. 9, Aug.

27,1965, pp. 31-33.7

The question here is whether a clearly established legal

right will be applied in the only way it can be meaningful,

or whether California and its courts will continue to sweep

this issue under the rug.

7 For other comments on the causes of the Watts riots, see, e.g.,

“No Panacea,” The Christian Century, Vol. L X X X II , No. 34, Aug.

25,1965, pp. 1027, 1028; “Los Angeles: And Now W hat?” , America,

Vol. 113, No. 9, Aug. 28,1965, p. 199.

2 2

W herefore, for the foregoing reasons, petitioners pray

that the writ of certiorari be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

L eroy D. Clark

Charles S tephen R alston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

R aymond C. Johnson

4840 W. Washington Blvd.

Los Angeles, California

H erman R. S m ith

600 East 103rd Street

Los Angeles, California

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Attorneys for Petitioner

A P P E N D I C E S

APPENDIX A

I n the

SUPREME COURT OF CALIFORNIA

No..............

D oris W atkins, L arry D. R obinson, Janelle H ylton , and

Clarence L. P roctor,

Petitioners,

—vs.—

T he Superior Court, L os A ngeles County, California,

and J. Howard Ziemann, Joseph L. Call, Fred P. Per-

raga, John G-. Barnes, Vernon Spencer, Mark Brandler,

Robert Clifton, Bernard Lawler, Joseph A. Wapner,

Raymond Roberts, Bernard S. Selber, Richard S. C.

Hayden, Edward C. Olson, Kathleen Parker, Mario L.

Clinco, Joseph Sprankle, Jr., and Robert Feinerman as

Judges,

T he M unicipal Court of L os A ngeles, California, and

Maurice T. Leader, Irwin J. Nebron and Philip M. Saeta

as Judges

T he Juvenile Court of L os A ngeles County, California,

and William E. MacSaden as Judge.

Petition for Writ of Prohibition and Mandamus

To: The above-named Respondents as Judges of the

Superior Court of Los Angeles County, California, and

the Municipal Court of the City of Los Angeles, California

and Juvenile Court, Los Angeles County, California. Now

2a

come the Petitioners named herein and petition this Hon

orable Court for the issuance of a Writ of Prohibition and

Mandamus directed to the Respondents for the causes and

on the grounds named herein as follows:

1. Petitioners Doris Watkins, Larry D. Robinson, Jan-

elle Hylton, and Clarence L. Proctor, are all Negro cit

izens of Los Angeles County, California, who were arrested

and charged with crimes for participation in rioting oc

curring in Los Angeles County, California, between August

11 and August 20, 1965. Petitioners have had bail set in

their initial arraignment, have completed their preliminary

hearings, and have been given a date for trial. Petitioner

Clarence L. Proctor is presently in custody in the Hall of

Justice in Los Angeles, California. All other Petitioners

are released on bail or on their own recognizance. Peti

tioners are indigent and unable to pay for the services of

private counsel.

2. The Respondents are J. Howard Ziemann, Joseph

L. Call, Fred P. Perraga, John Gr. Barnes, Vernon Spencer,

Mark Brandler, Robert Clifton, Bernard Lawler, Joseph

A. Wapner, Raymond Roberts, Bernard S. Selber, Richard

S. Hayden, Edward C. Olson, Kathleen Parker, Mario L.

Clinco, Joseph Spankle, Jr. and Robert Feinerman, Judges

of the Superior Court, Los Angeles County, California;

Maurice T. Leader, Irwin J. Nebron and Philip M. Saeta,

Judges of the Municipal Court of the City of Los Angeles,

California and William E. MacSaden, Judge of the Ju

venile Court, Los Angeles County, California. Respon

dents Ziemann, Call, Perraga, Barnes, Spencer, Brandler,

Clifton, Lawler, Wapner, Roberts, Selber, Hayden, Olson,

Parker, Clinco, Spankle, and Feinerman are vested with

3a

jurisdiction to conduct preliminary hearings, arraignment

for pleas and trials of petitioners and other defendants

charged with felony violations. Respondents Leader,

Nebron, and Saeta have the authority to inform Petitioners

and other defendants appearing in the Municipal Court of

the charges placed against them, to set bail pending a

preliminary hearing and to preside at the trials of de

fendants charged with misdemeanors. Respondent Mac-

Saden conducts proceedings in the Juvenile Court for mi

nors charged with misdemeanors and felonies. All of the

said Respondents have the authority and duty to inform

defendants of their right to counsel and to secure imme

diate appointment of counsel to indigent defendants who

are financially unable to secure representation.

3. Respondents have failed to secure adequate legal rep

resentation for the indigent Petitioners in the following

particulars:

(a) Respondent Judges of the Municipal Court

failed to appoint private counsel or a public defender

to represent Petitioners at the initial arraignment,

and made no inquiry as to Petitioners’ financial ability

to retain counsel for this proceeding. Petitioners were

given no time to secure counsel for said arraignments

and were prejudiced thereby when Respondents set

bail in the Municipal Court at two to three times the

amount ordinarily set for defendants with like charges.

Bail was set at excessive and discriminatory levels to

insure Petitioners continued incarceration, thereby

assuming the guilt of all Petitioners, prior to proof

of the charges against them. The Petitioners, being

without Counsel in said arraignments, were unable to

4a

challenge the violations of their constitutional and

statutory rights.

The facts of this allegation are supported by affida

vits of Petitioners Watkins, Hylton, and Proctor, at

tached hereto.

(b) All of the said Respondents have failed and

refused to appoint private counsel not associated with

the Public Defender’s office although the legal and in

vestigative staff of the Public Defender’s office has not

been expanded sufficiently to give adequate time for

preparation and investigation to defend Petitioners.

Petitioners have had necessarily brief and cursory

consultation with the public defenders in the pre-trial

proceedings. (See affidavits of Petitioners Watkins,

Hylton, and Proctor.) Neither of the Petitioners have

been continuously represented by one public defender

through the successive proceedings, resulting in each

public defender having to freshly acquaint himself with

the case when he receives it. (See affidavit of Peti

tioners Watkins, Hylton, and Proctor.) The Public

Defender has never been required to handle the cases

of over 4,000 defendants with multiple charges during

a six-week period, such as occurred after the riots

began. In September, 1965 the County Public Defen

der’s Office disbanded and the authority of the County

office was expanded to include misdemeanors as well

as felonies. The County office absorbed the bulk of the

City Staff, but the consolidation has not affected the

total legal staff available to service the caseload. Pri

vate Counsel, associated with groups such as the Na

tional Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the

5a

United Civil Rights Committee have represented indi

gent persons without compensation. They have re

ceived more requests for representation from persons

presently by the Public Defender’s Office. (See affida

vit of Petitioner Proctor.)

The above-named groups and the Los Angeles County

Bar Association have furnished the Respondents with lists

of attorneys who are willing to accept court appointment

to represent indigent persons arrested in the riots. The

Respondents have failed to make appointments of private

counsel from these lists in sufficient numbers to relieve the

overextended caseload of the Public Defender’s Office, and

have limited the appointment of private counsel to in

stances where there would be a conflict of interest for the

Public Defender to represent the defendant. (See affidavit

of Petitioner Robinson.)

4. Petitioners bring this suit as a class action on their

behalf and on behalf of all other Negro persons in Los

Angeles County arrested since August 11, 1965 for par

ticipation in rioting, who are similarly affected by the

denial of adequate legal counsel. Petitioners allege on in

formation and belief that over 4,000 persons have been

charged with misdemeanors and felonies in circumstances

similar to their own. The members of the class are so

numerous as to make it impracticable to bring them all

individually before this Court; there being common ques

tions of law and fact involved, and common grievances

arising out of common wrongs, and common relief is sought.

The Petitioners fairly and adequately represent the inter

est of their class.

6a

5. The Respondents lack jurisdiction to continue crimi

nal or juvenile proceedings where indigent persons are

denied legal counsel.

6. The members of Petitioners’ class have no plain, ade

quate, and speedy remedy by appeal or in any other man

ner to secure adequate representation by counsel prior to

trial. Public defenders representing indigent persons in

Petitioners’ class have not raised the objection that these

parties are being denied counsel, and therefore criminal

trials and juvenile proceedings are being conducted in which

the deprivation of constitutional and statutory rights will

not be raised. The members of the Petitioners’ class are

threatened with irreparable injury in that they face prose

cution with the defense of private counsel who are uncom

pensated and without funds to make investigation, or are

represented by the Public Defender’s Office which is over

extended. Unless this Court restrains the Respondents and

orders the protection prayed for herein, Petitioners and

members of the class will be tried in proceedings totally

in violation of their constitutional and statutory rights,

and deprived of equal protection of the laws in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

7. Petitioners file their application for Writ of Prohibi

tion and Mandamus in this Court in the first instance be

cause three of the Petitioners are to be tried in October,

1965, with Petitioner Robinson’s trial to begin October 15,

1965. Petitioners allege on information and belief that the

trials of other members of the class are in progress or

will be conducted during the second week of October, 1965.

Petitioners’ application for Writ of Prohibition and Man

damus is of grave public importance, as it raises funda

7a

mental questions of the constitutionality and authority of

the Respondents to proceed with criminal prosecutions of

over 4,000 defendants.

W herefore, your Petitioners pray that an alternative

Writ of Prohibition and Mandamus issue out of and under

the seal of this Honorable Court directed to the Respon

dents above named commanding them to :

1) Appoint counsel with adequate preparation, in

vestigation and counseling before conducting any fur

ther proceedings;

2) Nullify any prior proceedings in which Peti

tioners or members of their class, after securing ade

quate counsel, can demonstrate they were prejudiced

by the lack of counsel;

3) Furnish the members of Petitioners’ class with

lists of private counsel, if the Public Defender’s Office

is found to have an inordinate caseload, and to provide

compensation for such counsel as are chosen by the

indigent defendants.

In the alternative Petitioners pray that the Respondents

be made to show cause before this Court, at a time and place

to be fixed, why they should not be restrained and enjoined

from taking any further proceedings in the causes men

tioned herein, and for such other, further and additional

relief as to the Court may seem just and proper in the

premises.

8a

State of California,

County of L os A ngeles, s s . :

Doris Watkins, Janelle Hylton, Larry D. Robinson, and

Clarence L. Proctor, being duly sworn, say: that they are

the Petitioners in the above-entitled action; that they have

read the foregoing petition for Writ of Prohibition and

Mandamus, and know the contents thereof; that the facts

alleged in the writs are true of their own knowledge, and all

other matters stated in the writs are alleged on information

or belief, and as to those matters they believe them to be

true.

L arky D ike R obinson

Petitioner

M bs. Janelle H ylton

Petitioner

M bs. D orris W atkins

Petitioner

Subscribed and sworn to before me this

6th day of October, 1965.

S id E. Campbell

Notary Public

My Commission Expires May 26,1967

9a

Clarence P roctor

Petitioner

Subscribed and sworn to before me this

7th day of October, 1965.

R obert A. W ard, Jr.

Notary Public

My Commission Expires July 11,1967

R aymond L. J ohnson

4840 W. Washington Blvd.

Los Angeles, California

H erman T. Sm ith

600 E. 103rd Street

Los Angeles, California

Jack Greenberg

L eroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Petitioners

10a

Affidavits

S tate of California,

County of L os A ngeles, s s . :

I, Janelle Hylton, being duly sworn, deposes and says:

1. I am a Petitioner in the attached application for Writ

of Prohibition and Mandamus and make these statements

in support thereof.

2. I was arrested on Saturday, August 14, 1965 and was

arraigned on Thursday, August 19, 1965. I was not repre

sented by counsel at this arraignment and I was informed

that I was charged with burglary, and my bail set at

$4500. I was unable to meet the bail of $4500 and remained

in jail until my preliminary hearing.

3. I appeared in court on Tuesday, August 24, 1965 for

a preliminary hearing. Between my arraignment on Thurs

day, August 19, 1965, and until I arrived in court on Tues

day, August 24, 1965,1 had not been interviewed by anyone

from the Public Defender’s office. At the preliminary hear

ing on Tuesday, August 24,1965 the court appointed a pub

lic defender, and he interviewed me concerning my case

for approximately five minutes. The court found probable

cause for binding me over for trial, and I was released on

my own recognizance.

4. On Wednesday, September 8, 1965, I reappeared in

court to give my plea. The court assigned a public defender

to me who talked with me about ten minutes concerning my

financial status and the circumstances of my arrest. This

11a

public defender was not the public defender who appeared

with me at the preliminary hearing.

5. On Thursday, September 16, 1965 I reappeared in

court and entered a plea of not guilty. The public defender

who represented me on this date had not appeared with me

at the preliminary hearing, nor was this the public de

fender whom I had talked with on Wednesday, September

8,1965.

6. I received a letter from the Public Defender’s office

stating that Mrs. Florence Mills was assigned to defend

me, and I called and have secheduled an appointment for

Friday, October 8, 1965. During the entire period after

my arrest and release on my own recognizance, no investi

gator from the Public Defender’s office has called me or

visited my home to make an investigation of the facts.

7. My trial is secheduled for November 10, 1965.

I, D oris W atkins, being duly sworn, deposes and says:

1. I am a Petitioner in the attached application for Writ

of Prohibition and Mandamus and make these statements

in support thereof.

2. I was arrested on Saturday, August 14,1965 and taken

for arraignment on Tuesday, August 17, 1965. I was in

formed I was charged with burglary and my bail was set

at $4900. I was unable to meet bail. No attorney repre

sented me at this proceeding.

3. I appeared in court on Friday, August 21,1965 for the

preliminary hearing. The court appointed a public de

12a

fender. He informed me that he didn’t know anything

about my case and didn’t have time to talk to me about it.

He said that he only wanted information in order to secure

a reduction in my bail. He inquired only as to my name, my

address, number of my children, and if I had any prior

convictions. The court found probable cause for holding

me for trial and bail was reduced to $250. I secured my

release under this bail.

4. I reappeared in court on Monday, September 13, 1965,

and entered a plea of not guilty. The public defender who

appeared on my behalf had not represented me in any

prior hearing.

5. A trial date was set for Monday, October 25,1965.

6. I received a letter from the Public Defender’s office

and arranged an interview with a public defender on

Wednesday, September 29, 1965. We talked for approxi

mately 25 minutes concerning the circumstances of my

arrest.

7. At no time after my arrest or to date has an investi

gator for the Public Defender’s office interviewed me or

inquired of me as to the facts of the charges against me.

I, Clarence L. P roctor, being duly sworn, deposes and

sa y s:

1. I am a Petitioner in the attached application for Writ

of Prohibition and Mandamus and make these statements

in support thereof.

2. I was arrested on Saturday, August 14, 1965 and ar

raigned on August 18, 1965. At the arraignment I was

13a

informed that I was charged with burglary and bail was

set at $4950. I was unrepresented by counsel at this pro

ceeding and no inquiry was made as to my length of resi

dence in the county, prior convictions, or present employ

ment. I was unable to pay the bail for release.

3. I reappeared in court on Friday, August 20, 1965

for a preliminary hearing. The court, at the start of this

proceeding, appointed a public defender to represent me.

I had had no interview with the public defender or with

any investigator from the Public Defender’s office prior to

the start of this proceeding. The public defender consulted

with me approximately two minutes concerning the cir

cumstances of my arrest. The court found probable cause

to hold me for trial. Bail was reduced to $2500. I was un

able to meet the reduced bail and presently continue in

custody.

4. On Friday, September 3, 1965 a man from the Public

Defender’s office who was not a public defender, gave me

forms to fill out to secure my release on my own recogni

zance.

6. My trial is set for October 29, 1965. After the pre

liminary hearing on Friday, August 20, 1965 until Sunday,

October 3, 1965, no one from the Public Defender’s office

interviewed me, although I wrote letters to the Public De

fender’s office requesting consultation to prepare my de

fense. When the public defender did visit me on October

3, 1965 he informed me that he had been very busy and

was therefore unable to consult with me earlier. We talked

for approximately five or six minutes. During the period

14a

prior to October 3, 1965, when I saw no one from the Pub

lic Defender’s office, I wrote to the N.A.A.C.P. requesting

legal assistance.

7. No investigator from the Public Defender’s office has

visited me to secure facts concerning the charges against

me.

I, L arky D. R obinson, being duly sworn, deposes and

says:

1. I am a Petitioner in the attached application for Writ

of Prohibition and Mandamus and make these statements

in support thereof.

2. I was arrested on Thursday, August 12, 1965 and was

bailed out Friday, August 13,1965, bail being set at $250.

3. I was arraigned on Wednesday, August 18, 1965 and

was informed that I was charged with the misdemeanor of

disturbing the peace. I pleaded not guilty and bail was

set at $1000. I was unrepresented in this proceeding.

4. On Saturday, August 21, 1965 I was bailed out again.

I reappeared in court on September 7, 1965 for a prelimi

nary hearing. I informed the court I wanted to seek coun

sel at the N.A.A.C.P. The Judge urged me, even after

I made known my desire to seek representation by the

N.A.A.C.P., to accept the representation of the Public

Defender’s office. I refused the appointment of the public

defender.

5. I have made contact with private counsel of the

N.A.A.C.P. and desire their representation. I am not able

to pay private counsel.

6. My trial is scheduled for October 15, 1965.

15a

I n the

DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL OF

THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

Second A ppellate D istrict D ivision T wo

Minutes of Division Two

October 18, 1965

Civil No. 29877

.. ■— ..................................................... - - — — ------------------ —

W atkins, et al.

— vs.—

S uperior Court of L os A ngeles County

The Court: Petition for writ of prohibition and mandate

denied.

16a

I n the

SUPREME COURT OF CALIFORNIA

[Names of parties omitted]

Petition for Hearing

Comes now the petitioners named herein and petition

this Honorable Court to grant a hearing for review of the

denial by the District Court of Appeals, Second District,

of petitioners’ writ of prohibition and mandamus. As

grounds for such relief, petitioners state the following:

1. Petitioners’ writ of prohibition and mandamus, filed

in this court on October 8, 1965, was transferred to the

District Court of Appeals, Second District, on October 11,

1965.

2. The District Court of Appeals on October 18, 1965

denied the petition for writ of prohibition and mandamus,

without opinion. A copy of the order of the court is at

tached hereto.

3. The petitioners are four indigent Negro persons

charged with crimes for participating in riots occurring

in Los Angeles County, California between August 11 and

20, 1965. The writ of prohibition and mandamus was di

rected to the Municipal Court of the City of Los Angeles,

California, the Superior Court and the Juvenile Court of

Los Angeles County, which courts have the responsibility

17a

of conducting adult and juvenile proceedings on charges

against all persons arrested in the riots.

4. Petitioners tiled the Writ of Prohibition and Man

damus as a class action on behalf of themselves and all

other Negro persons arrested in the riots who are being

tried before the respondents. The Petition alleged the fol

lowing facts, which facts are more particularized in a copy

of the Writ of Prohibition attached hereto:

a. Petitioners and other indigent defendants were

subjected to excessive and discriminatory bail at their

initial arraignment and were unrepresented during or

prior to this proceeding.

b. Respondents have sought to have the Public De

fender’s Office carry the burden of representing the

bulk of over 4,000 defendants with multiple charges

in pre-trial and trial proceedings in which the Public

Defender’s Office had not had sufficient time or per

sonnel to prepare, consult with the defendant or in

vestigate the charges to conduct an adequate defense.

Private associations such as the N.A.A.C.P. have un

dertaken a portion of the representation of indigent

defendants without compensation and have received

no funds to conduct adequate investigations. These

private associations and the Los Angeles County Bar

Association have furnished the respondents with lists

of attorneys willing to accept court appointments to

represent the members of petitioners’ class, but

respondents failed to make use of this source of rep

resentation in sufficient numbers to relieve the over

extended case load of the Public Defender’s Office.

18a

c. Minors have been tried in Juvenile Court without

adequate counsel from the Public Defender’s Office,

or without representation by any attorney.

5. The Petition for Writ of Prohibition and Mandamus

asserts that the respondents have failed to secure adequate

legal representation for petitioners and other indigent de

fendants in violation of the equal protection and due process

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution, Article I, Section 2 of the California Consti

tution and state statutes governing appointment of counsel.

In particular, respondents have violated petitioners’ rights

in the following manner:

a. The Juvenile Court has failed to appoint counsel

for every indigent juvenile who is charged with the

commission of a misdemeanor or felony.

b. The Municipal Court, and judges from the Su

perior Court sitting as Municipal judges, failed to

secure indigent persons counsel prior to the arraign

ment held immediately after their arrest.

c. Petitioners and members of their class have not

been accorded a right to counsel equal to that ac

corded to indigent defendants arrested and tried prior

to the riots of August 11, 1965.

d. Appointment of the public defender was inade

quate as there was insufficient time for consultation

and investigation to conduct a proper defense.

e. Respondents failed to appoint private counsel

although the Public Defender’s Office was not staffed

to service the inordinate number of criminal cases

arising over a two to three-week period.

19a

f. Respondents failed to accord indigent defendants

court-appointed counsel of their own choosing where

such defendants did not wish to be represented by the

public defender.

6. Writ of Mandamus will lie since respondents have

failed to perform the duty enjoined upon them by law to

appoint adequate counsel to petitioners and other indigent

defendants. Writ of prohibition will lie since respondents

lack jurisdiction to conduct juvenile or criminal proceed

ings without acquiring adequate legal representation for

persons unable to afford private counsel.

7. Petitioners request a hearing to settle serious ques

tions of law concerning the nature and scope of the rights

of over 4,000 indigent defendants to adequate legal rep

resentation.

Respectfully submitted,

R aymond L. J ohnson

4840 West Washington Blvd.

Los Angeles, California

H erman T. S m ith

600 East 103rd Street

Los Angeles, California

Jack Greenberg

L eroy D. Clark

Charles S tephen R alston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Petitioners

20a

Order Due

November 17, 1965

Order Denying Hearing

A fter Judgment by D istrict Court op A ppeal

2nd District, Division 2, Civil No. 29877

In the

SUPREME COURT

OP THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

IN BANK

W atkins

Superior Court of the County of L os A ngeles

for hearing D enied.

F iled N ov 3—1965

petition

T raynor, Chief Justice

21a

APPENDIX B

California Statutes Involved

Calif. Penal Code §858:

Informing Accused of Nature of Charge and Right to

Counsel.—When the defendant is brought before the

magistrate upon an arrest, either with or without war

rant, on a charge of having committed a public offense,

the magistrate must immediately inform him of the

charge against him, and of his right to the aid of

counsel in every stage of the proceedings. If it ap

pears that the defendant may be a minor, the magis

trate shall ascertain whether such is the case, and if

the magistrate concludes that it is probable that the

defendant is a minor, . . . he shall immediately either

notify the parent or guardian of the minor, by telephone

or messenger, of the arrest, or appoint counsel to rep

resent the minor.

Calif. Penal Code §859:

Time to Procure Counsel.—When the defendant is

charged with the commission of a public offense, over

which the superior court has original jurisdiction, by

a written complaint subscribed under oath and on file

in a court within the county in which the public offense

is triable, he shall, without unnecessary delay, be taken

before a magistrate of the court in which such com

plaint is on file. The magistrate shall immediately

deliver to him a copy of the complaint, inform him of

his right to the aid of counsel, ask him if he desires the

22a

aid of counsel, and allow him a reasonable time to send

for counsel; and the magistrate must, upon the request

of the defendant, require a peace officer to take a mes

sage to any counsel whom the defendant may name, in

the judicial district in which the court is situated. The

officer must, without delay and without fee, perform

that duty. If the defendant desires and is unable to

employ counsel, the court must assign counsel to defend

him. If it appears that the defendant may be a minor,

the magistrate shall ascertain whether such is the case,

and if the magistrate concludes that it is probable that

the defendant is a minor, he shall immediately either

notify the parent or guardian of the minor, by tele

phone or messenger, of the arrest, or appoint counsel

to represent the minor.

Calif. Penal Code §859a:

Felony Plea Before Magistrate. If the public offense

charged is a felony not punishable with death, the

magistrate shall immediately upon the appearance of

counsel for the defendant read the complaint to the

defendant and ask him whether he pleads guilty or

not guilty to the offense charged therein and to a pre

vious conviction or convictions of crime if charged;

thereupon, or at any time thereafter, while the charge

remains pending before the magistrate and when his

counsel is present, the defendant may, with the consent

of the magistrate, and the district attorney or other

counsel for the people, plead guilty to the offense

charged or to any other offense the commission of

which is necessarily included in that with which he is

charged, or to an attempt to commit the offense charged

23a

and to the previous conviction or convictions of crime

if charged; and upon such plea of guilty, the magistrate

may then fix a reasonable bail as provided by this code,

and upon failure to deposit such bail or surety, shall

immediately commit the defendant to the sheriff and

certify the case, including a copy of all proceedings

therein and such testimony as in his discretion he may

require to be taken, to the superior court, and there

upon such proceedings shall be had as if such defendant

had pleaded guilty in such court. The foregoing pro

visions of this section shall not be construed to au

thorize the receiving of a plea of guilty from any

defendant not represented by counsel. . . .

Calif. Penal Code §987:

Defendant, on Arraignment to Be Informed of His

Right to Counsel, When Court to Assign Counsel. If

the defendant appears for arraignment without counsel,

he must be informed by the court that it is his right

to have counsel before being arraigned, and must be

asked if he desires the aid of counsel. If he desires

and is unable to employ counsel, the court must assign

counsel to defend him.

Calif. Penal Code §987a:

Compensation of Counsel by County. In any case in

which counsel is assigned in the superior court to

defend a person, including a person who is a minor,

who is charged therein with the commission of a crime,

or is assigned in a municipal or justice’s court, or

justice court as established pursuant to the Municipal

and Justice Court Act of 1949, to represent such a

24a

person on a preliminary examination in snch a court

and who desires but who is unable to employ counsel,

such counsel, in a county, or city and county, in which

there is no public defender, or in a case in which the

court finds that because of conflict of interest or other

reasons the public defender has properly refused to

represent the person accused, shall receive a reason

able sum for compensation and for necessary expenses,