Estes v. Dallas NAACP Appendix

Public Court Documents

May 1, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Estes v. Dallas NAACP Appendix, 1979. 9bdde323-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3c9e7f71-c699-4c2d-bb4a-fd93a29fae3f/estes-v-dallas-naacp-appendix. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

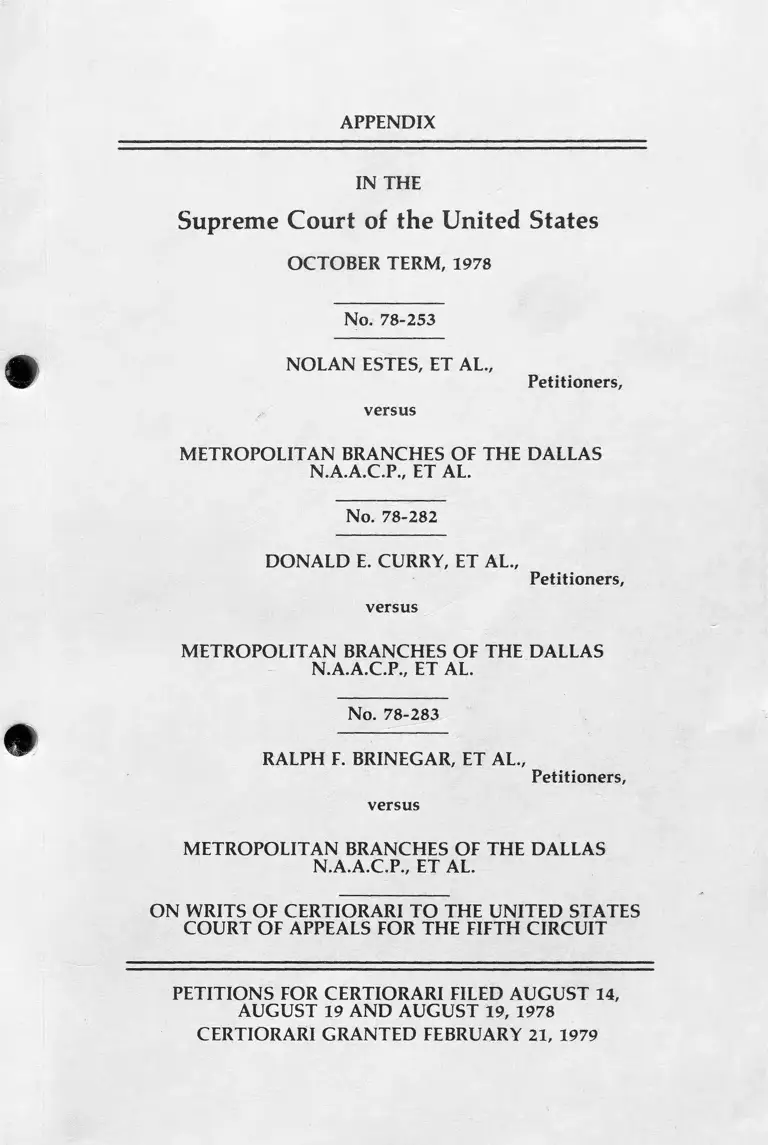

APPENDIX

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

No. 78-253

NOLAN ESTES, ET AL.,

Petitioners,

versus

METROPOLITAN BRANCHES OF THE DALLAS

N.A.A.C.P., ET AL.

No. 78-282

DONALD E. CURRY, ET AL.,

Petitioners,

versus

METROPOLITAN BRANCHES OF THE DALLAS

N.A.A.C.P., ET AL.

No. 78-283

RALPH F. BRINEGAR, ET AL.,

Petitioners,

versus

METROPOLITAN BRANCHES OF THE DALLAS

N.A.A.C.P., ET AL.

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

PETITIONS FOR CERTIORARI FILED AUGUST 14,

AUGUST 19 AND AUGUST 19, 1978

CERTIORARI GRANTED FEBRUARY 21, 1979

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

No. 78-253

NOLAN ESTES, ET AL„

Petitioners,

versus

METROPOLITAN BRANCHES OF THE

DALLAS N.A.A.C.P., ET AL„

Respondents.

No. 78-282

DONALD E. CURRY, ET AL„

Petitioners,

versus

METROPOLITAN BRANCHES OF THE

DALLAS N.A.A.C.P., ET AL„

Respondents.

11

No. 78-283

RALPH F. BRINEGAR, ET AL.,

Petitioners,

versus

METROPOLITAN BRANCHES OF THE

DALLAS N.A.A.C.P., ET AL.,

Respondents.

«

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

INDEX

Chronological List of Relevant Docket

Entries .............................................

Page

___1

Memorandum Opinion, Filed July 16,

1971 ................ ................. .................. Brinegar

Pet.App.A-1

Order permitting NAACP to intervene,

Filed August 25, 1975 ........................

Opinion and Order, Filed March 10,

1976 .............................. .......................

13

Estes

Pet.App.4a

Supplemental Order, Filed March 15,

1976 ............................................ ....... Estes

Pet.App.45a

i

Supplemental Opinion and Order, Filed

April 7, 1976 .......................................... Estes

Pet.App.46a

Final Order, Filed April 7, 1976 .......... Estes

Pet.App.53a

Supplemental Order, Filed April 15,

1976 ............................... ............... . . Estes

Pet.App.121a

Supplemental Order, Filed April 20,

1976 ................................................... Estes

Pet.App.126a

Page 4 of Plaintiffs' Brief in Support of

Motion for Attorneys' Fees and Costs,

Filed April 30, 1976 ......................... ...................... 14

Page 3 of Memorandum Opinion (Re at

torneys' fees and costs), Filed July 20,

1976 .................................... ................................... 15

Supplemental Order Changing Atten

dance Zones of James Madison High

School and Lincoln High School, Filed

August 18, 1976 ........................... . Estes

Pet.App.127a

Opinion of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, Filed

April 21, 1978 ................................... . . Estes

Pet.App.130a

INDEX (Continued)

Page

INDEX (Continued)

Page

Judgment of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, Dated

April 21, 1976 .......................................................... 16

Letter from Clerk of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

advising the Court had denied Petition

for Rehearing, Dated May 22, 1978 . . Estes

Pet.App.146a

Motion for Stay of Mandate in the Unit

ed States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit, Filed May 26, 1978 .. . Estes

Pet.App.148a

Order of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit denying

Motion for Stay of Mandate, Filed

August 14, 1978 ...................................... .............. 16

Quotation of language prepared by

Petitioners Brinegar, et al., referring

to one or more of the opinions, orders,

decisions or judgments of the lower

Courts and where it may be found;

said language designated by that party

to be included in the Appendix ........................ .. 1'

Quotation of language prepared by

Petitioners Curry, et al., referring to

one or more of the opinions, orders,

decisions or judgments of the lower

V

Courts and where it may be found;

said language designated by that party

to be included in the Appendix .......................... 19

Quotation of language prepared by

Respondents Tasby, et al., referring to

one or more of the opinions, orders,

decisions or judgments of the lower

Courts and where it may be found;

said language designated by that party

to be included in the Appendix ..................... 20

Quotation of language prepared by

Respondents Tasby, et al., referring to

the fact that a Petition for Certiorari

was filed by Petitioners Estes, et al., to

review the decision of the Court of

Appeals reported at 517 F.2d 92 (5th

Cir. 1975); said language designated

by that party to be included in the

Appendix ........ ................... . .................. 20

Quotation of language prepared by

Respondents Tasby, et al., referring to

the fact that the above-mentioned

Petition for Certiorari was denied and

where denial is reported; said lan

guage designated by that party to be

included in the Appendix

INDEX (Continued)

Page

20

Trans. App.

Pages Pages

Excerpts from Transcript of Proceedings:

INDEX (Continued)

Testimony of Dr. Nolan Estes,

Witness on Behalf of Defen

dants

Direct Examination . . . . . . . 62 21

Cross Examination ............ 278 36

Re-Direct Examination . . . . 404 37

Testimony of Kathlyn Gilliam,

Witness on Behalf of Plaintiffs

Cross Examination ........ ... 54 40

T e s t i mo ny of Dr. Jose

Cardenas, Witness on Behalf of

Plaintiffs

Cross Examination . . . . . . . 333 44

Testimony of Dr. Charles V.

Willie, Witness on Behalf of

Plaintiffs

Cross Examination ............ 134 50

Testimony of Yvonne Ewell,

Witness on Behalf of Plaintiffs

Direct Examination ............ 192 59

Cross Examination . .......... 213 65

Testimony of Edward B. Clout-

man, III, Witness on Behalf of

Plaintiffs

Direct Examination ............ 231 70

Cross Examination . . . . . . . 329 75

V ll

INDEX (Continued)

Trans. App.

Pages Pages

Testimony of Dr. Charles

Hunter, Witness on Behalf of

NAACP-Intervenors

Direct Examination . . . . . . . 6 92

Cross Examination . 106 96

Testimony of Dr. Josiah C.

Hall, Jr., Witness on Behalf of

the Court

Direct Examination . 123 100

P r e - T r i a l H e a r i n g re

Educational Task Force of the

Dallas Alliance and Court

permitting Educational Task

Force to intervene as Amicus

Curiae . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 295 103

Testimony of Dr. Paul Geisel,

Witness on Behalf of the Court

Direct Examination . . .. 2 122

Cross Examination . . . . 50 132

Examination .......... ....... . . . 369 155

Testimony of Susan Murphy,

Witness on Behalf of Brinegar-

Intervenors

Direct Examination . . . . . . . 332 163

T estimony of Ram Singh,

Witness on Behalf of Brinegar-

Intervenors

Direct Examination . . . . . . . 357 168

viii

INDEX (Continued)

Trans. App.

Pages Pages

Testimony of William Darnell,

Witness on Behalf of Brinegar-

Intervenors

Direct Examination ........... 377 174

Testimony of Robert Lee

Burns, Witness on Behalf of

Brinegar-Intervenors

Direct Examination . . . . . . . 400 190

Testimony of Evelyn Dun-

savage, Witness on Behalf of

Brinegar-Intervenors

Direct Examination ........... 15 191

Testimony of Rene Martinez,

Witness on Behalf of the Court

Direct Examination . . . . . . . 361 196

Excerpts from Transcript of

Hearing on Plaintiffs' Motion

for Further Relief .................. 82 198

Excerpts from Transcript of

Called Hearing of judge Taylor . 2 205

Excerpts from Transcript of

Proceedings of February 24,

1977

Testimony of Dr. Nolan Estes,

Witness on Behalf of Defen

dants

Direct Examination ............ 5 216

INDEX (Continued)

Defendants' Exhibit No. 1 — Map

(Reduced in size) .................... 219

Defendants' Exhibit No. 2 — Map

(Reduced in size) ........... 220

Defendants' Exhibit No. 3 — Map

(Reduced in size) .................... 221

Defendants' Exhibit No. 11,

Page

pages 1 and 2 — Dallas In

dependent School District Stu

dent Assignment Plan for

Elementary and Secondary

Schools ................. 222

Defendants' Exhibit No. 13 —

Historical Enrollment of Dallas

Independent School District . 224

Defendants' Exhibit No. 17 —

Minutes of Called Board

Meeting of Dallas Alliance . . 226

NAACP's Exhibit No. 2, pages 6

through 8 — Proposed Plan for

D esegregation . 230

Plaintiffs' Exhibit No. 16, pages 2,

9, 34, 36, 38, 39 and 41 — Plain

tiffs' Desegregation Plans A

and B .................................. .. 234

X

Court's Exhibit No. 9 — Letter

from Dallas Alliance Education

Task Force dated March 3,

1976 ...................... . ............... 250

Hall's Exhibit No. 5, pages 14

through 19 — A Potential Plan

for Compliance with Rulings

for Operating Schools in

Dallas, Texas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 251

Curry's Exhibits 6 through 9 —

INDEX (Continued)

Page

The Effect of Court-Ordered

Busing on White Flight (Reduc

ed in s iz e ) ..................... 260

Brinegar's Exhibit No. 6, pages vi

and 27 — Report No. 2 of East

Dallas Demonstration . . . . . . . 265

Certificate of Service . .............. 268

I

In the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Texas, Dallas Division

EDDIE MITCHELL TASBY, et al

versus CA NO. 3-4211-C

DR. NOLAN ESTES, et al

Chronological List of Relevant Docket Entries:

DATE PROCEEDINGS

10- 6-70 — Plaintiffs' Complaint

10-15-70 — Plaintiffs' First Amended Complaint

10-26-70 — Defendants' Answer

7- 2-71 — James T. Maxwell's Motion to Intervene

(Proposed Intervener's Complaint at

tached)

7- 9-71 — Donald E. Curry, Gerald A. Van Winkle,

Joe M. Gresham, Edmund S. Rouget and

Robert A. Overton, individually and as

next friends for their children, Motion to

Intervene as Defendants with Affirmative

Pleas (Defenses and Claims in Interven

tion attached)

7-12-71 — Opposition and Objections of the Defen

dants to Interventions

7-16-71 — Memorandum Opinion

7-22-71 — Order Allowing Intervention as Defen

dants: that Donald E. Curry, Gerald A.

2

Van Winkle, Joe M. Gresham, Edmund S.

Rouget and Robert A. Overton have leave

to intervene in this cause and hereby made

a party Defendant to this cause.

8- 6-71 — Notice of Cross-Appeal on behalf of

Defendant-Intervenors Donald G. Curry,

et al.

8- 9-71 — Supplemental Order for Partial Stay of

judgment: (1) Par. 10-B of 8-2-71 judg

ment, pertaining to pairing/grouping of

Kimball, Carter and South Oak Cliff High

Schools; (2) Par. 10-C providing for the

satelliting of students from Hassell,

Browne, Wheatley, Ray, Frazier, Carr,

Anderson, Dunbar, Arlington Park, Ty

ler and Carver elementary school zones —

into high schools, as shown on Appendix

A of the Judgment; (3) Par. 11-B of said

Order pertaining to junior High Schools

and pairing Atwell, Browne, Hulcey,

Storey and Zumwalt; (4) Par. 11-C also

pertaining to junior High Schools and

pairing Stockard, Edison and Sequoyah;

and (5) Par. 11-D pertaining to satelliting

students from Hassell, Harris, Arlington

Park, Tyler, and part of Carver into junior

High Schools, as shown on Appendix B of

said Order, be and the same are hereby

stayed unto 1-10-72, and students assign

ed in the satellite zones by the August 2nd

Order are to be reassigned by the Board of

Education to appropriate High and Junior

High Schools, taking into consideration

capacity and establishment of a unitary

school system. In all other respects the

August 2nd Judgment shall remain in full

force and effect.

8-12-71 — Motion to Intervene as Defendant by the

City of Dallas

8-16-71 — Defendant-Intervenors Donald G. Curry,

et al Designation of Contents of Record

on Appeal

8-17-71 — Supplemental Opinion Regarding Partial

Stay of Desegregation Order

8-17-71 — Transcript of Proceedings (Vols. I, II, III,

IV and V) with exhibits:

PX-1 thru 5, . . .

8-31-71 — Order granting permission that the City

of Dallas to intervene herein as defendant,

adopting the Answer of the Defendant

Dallas Independent School District as its

own with like effect as if fully repeated

8- 5-75 — The Metropolitan Branches of the Dallas

N.A.A.C.P/s Motion to Intervene

8-14-75 — Opposition and Objections of the Defen

dants to Intervention of the Metropoli

tan Branches of the Dallas NAACP

8-14-75 — Motion to Intervene by Strom, et al.

8-14-75 — Memorandum Brief in Support of Motion

to Intervene (by Strom, et al)

8-21-75 — Opposition and Objections of the Defen

dants to the Intervention of Dr. E.

Thomas Strom, et al.

3

8-21-75 — Plea in Intervention of Dr. E. Thomas

Strom, Charlotte Strom, et al

8-21-75 — Letter from attorney John W. Bryant re

questing addition of certain persons to

motion to intervene as parties to this

cause

8- 25-75 — Order that Dr. E. Thomas Strom, et al,

and the Metropolitan Branches of the

NAACP be permitted to file their respec

tive Pleas of Intervention and become par

ties in this cause

9- 3-75 — Complaint of Intervenors The Metro

politan Branches of the National Associa

tion for the Advancement of Colored Peo

ple

9- 9-75 — Motion to Intervene of Ralph F. Brinegar,

Wallace H. Savage, Evelyn T. Green,

Craig Patton, Dr. John A. Ehrhardt and

Harryette B. Ehrhardt, Richard L. Rod

riguez and Alicia V. Rodriguez, Mr. and

Mrs. Salomon Aguilar, Marjorie M.

Oliver, Mr. and Mrs. Ruben L. Hubbard,

Robert L. Burns, Dr. Percey E. Luecke, Jr.,

Dale L. Ireland and Barbara J. Ireland, and

Evelyn C. Dunsavage.

9-10-75 — Brief of East Dallas Residents in Support

of Motion to Intervene

9-10-75 — N.A.A.C.P/s Proposed Plan for Desegre

gation

9-10-75 — Dallas Independent School District Stu

dent Assignment Plan for Elementary and

Secondary Schools.

9-15-75 — Opposition and Objections of the Defen

dants to the Intervention of Ralph F.

Brinegar, et al.

9-17-75 — Order granting motion for leave to inter

vene filed by Ralph F. Brinegar, Wallace H.

Savage, Evelyn T. Green, Craig Patton,

Dr. John A. Ehrhardt and Harryette B.

Ehrhardt, Richard L. Rodriguez and Alicia

V. Rodriguez, Mr. and Mrs. Salomon

Aguilar, Marjorie M. Oliver, Mr. and Mrs.

Ruben L. Hubbard, Robert L. Burns, Dr.

Percey E. Luecke, Jr., Dale L. Ireland and

Barbara J. Ireland, and Evelyn C. Dun-

savage, on behalf of themselves and all

other persons similarly situated

9-18-75 — Intervenors' (Curry, et al) Motion in Op

position to Findings Not Based on

Evidence and Request for Production of

Data and Documents

9-24-75 — Plea of Intervention by East Dallas Resi

dents (Ralph F. Brinegar, et al)

9-26-75 — Order that Dr. Josiah C. Hall be and is

hereby appointed as expert advisor to the

court in the techniques of school desegre

gation

9-26-75 — DISD's Student Assignment Plan for

Elementary and Secondary Schools with 7

maps as exhibits.

9-26-75 — DISD's Corrections on student assign

ment plan

5

10- 7-75 — Interveners Dr. E. Thomas Strom's

Standards for Consideration in Formu

lating Plans for Additional School Deseg

regation

11- 14-75 — Letter dated November 12 ,1975 from the

Court of Appeals Stating: We have re

ceived a certified copy of an order of the

Supreme Court denying certiorari in the

above cause. This court's judgment as

mandate having already been issued to

your office, no further order will be forth

coming.

12- 29-75 — Court Appointed Advisor Hall's Deseg

regation Plan, with map

1- 12-76 — Plaintiffs' Proposal to Desegregate the

Dallas Independent School District, with

Maps

2- 17-76 — Desegregation Plan of Dallas Alliance, and

received comments of James W. Rutledge

(attached to Plan). Also received com

ments of black representatives (attached

to Plan)

2- 20-76 — Order that the Education Task Force of

the Dallas Alliance be granted the status

of Amicus Curiae for purpose of present

ing their ideas and/or Plan for desegrega

tion of the Dallas Independent School Dis

trict. Copies distributed in courtroom.

3- 3-76 — Letter from Jack Lowe, Sr. to Hon. W. M.

Taylor, Jr. transmitting revised plan of the

Dallas Alliance Education Task Force

6

3-10-76 — Memorandum Opinion and Order (. . .

that the modified plan of the Educational

Task Force of the Dallas Alliance filed

with the Court on March 3, 1976 is here

by adopted as the Court's plan for re

moval of all vestiges of a dual system re

maining in the Dallas Independent School

District and the school district is directed

to prepare and file with the Court a stu

dent assignment plan carrying into effect

the concept of said Task Force plan no

later than March 24, 1976)

Copies distributed to counsel in court

room

3-15-76 — Supplemental Order (. . . some questions

have arisen regarding the Court's adop

tion of the Dallas Alliance's plan. So that

there is no misunderstanding . . . the

Court intended by the order of March 10,

1976 to adopt the concepts suggested by

the plan of the Educational Task Force of

the Dallas Alliance. The staff of the school

district shall take these concepts and adapt

them to fit the characteristics of DISD.

The Court recognizes that during this

process, a certain amount of flexibility is

necessary. The Court expects the school

district to put into effect the concepts of

the Dallas Alliance plan. The specifics of

the desegregation plan for the DISD will

be embodied in the Court's final order

7

which will be entered in approximately

two weeks)

3-24-76 — Dallas Independent School District, A

Student Assignment Plan Carrying Into

Effect The Concept Of The Educational

Task Force Of The Dallas Alliance

3-26-76 — Dallas Independent School District's Mo

tion to Alter or Amend March 10, 1976,

Opinion and Order

3- 29-76 — Defendant DISD's Resolutions and Pro

posal On Non-Student Assignment Con

cepts

4- 1-76 — Addendum To Student Assignment Plan

by DISD.

4- 2-76 — (Mullinax, Wells, Mauzy & Babb) Plain

tiffs' Motion for Attorneys' Fees and

Costs

4- 5-76 — (Dallas Legal Services Foundation) Plain

tiffs' Motion for Attorney Fees and Costs

4- 7-76 — Final Order . . . in order to carry out the

concepts embodied in the desegregation

plan of the Educational Task Force of the

Dallas Alliance, the School Board of the

Dallas Independent School District is or

dered and directed to implement the fol

lowing items: Major Sub-Districts . . .

Student Assignment Criteria Within Sub-

Districts . . . the K-3 Early Childhood Ed

ucation Centers . . . the 4-8 Intermediate

and Middle School Centers . . . 9-12

Magnets and High Schools . . . Special

8

Programs . . . Majority to Minority

Transfer. . . Minority to Majority Trans

fers . . . Curriculum Transfers . . . Trans

portation . . . Changes in Attendance

Zones . . . Discipline and Due Process . . .

Facilities . . . Personnel . . . Accounting

System and Auditor . . . Tri-Ethnic Com

mittee . . . Retention of jurisdiction: To

the end that a unitary school shall be

achieved by the DISD, the U.S. District

Court for the Northern District of Texas

retains jurisdiction of this case)

4- 7-76 — Supplemental Opinion and Order

4-15-76 — Supplemental Order correcting clerical

errors in the student assignments made in

the Final Order per the attached Appen

dix . . . incorporated in and made a part of

the Final Order of April 7, 1976

4-20-76 — Notice of Appeal by Oak Cliff Branch and

the South Dallas Branch of the Dallas

N. A.A.C.P. from judgment entered April

7, 1976

4-20-76 — Supplemental Order sustaining Motion

of Plaintiffs to Alter or Amend (the judg

ment entered April 7, 1976 . . . ordered

that the . . . judgment, Sec. VI, subsec

tion 2 on page 11, be and hereby is amend

ed to read as follows: "2. English-as-a-

Second Language (ESL) programming

shall be expanded as rapidly as possible to

serve all students who are unable to ef-

9

fectively participate in traditional school

programming due to inability to speak and

understand the English language.

Emphasis shall be given to expanding ESL

programming in grades 7-8 and 9-12")

4-22-76 — Defendant DISD's Notice of Cross-

Appeal from April 7, 1976 Judgment

4-22-76 — Notice of Appeal by the John F. Kennedy

Branch of the Metropolitan Branch of

NAACP from the Student Assignment

Portion of the final judgment entered on

April 7, 1976

4-22-76 — Plaintiffs' Thelma Crouch, Ruth Jeffer

son, Bobbie Cobbins, Ludie Cobbin and

Richard Medrano Notice of Appeal from

Judgment entered April 7, 1976

4-23-76 — Interveners, Donald E. Curry, etal Notice

of Cross-Appeal from the Final Judgment-

Order entered April 7, 1976

4-26-76 — Notice of Cross Appeal by Plaintiffs Tasby

and Medrano from Student Assignment

Portions of Judgment entered April 7,

1976; in filing this notice of Cross Appeal

Ricardo Medrano withdraws his prior

Notice of Appeal filed on April 22, 1976.

(in forma pauperis)

4-30-76 — Plaintiffs' Brief in Support of Motion for

Attorneys' Fees and Costs

7-20-76 — Order that the DISD pay the following

named claimants the amounts set oppo

site their names: Sylvia M. Demarest (to

10

be paid to Dallas Legal Services $66,792;

Edward B. Cloutman III $32,514 . , . that

the motion of the DISD to set aside order

taxing costs against defendants and in

favor of plaintiffs is hereby denied

7- 20-76 — Memorandum Opinion

8- 9-76 — Transcript of Proceedings (6) (six vols)

held February 2, 1976. No exhibits

8- 9-76 — Transcript on Hearing on Motions held

September 16, 1975

8- 9-76 — Transcript on Hearing held December 18,

1975. No exhibits.

8-18-76 — Supplemental Order Changing Attend

ance Zones of James Madison High School

and Lincoln High School (. . . that the

Court's Final Order of April 7/ 1976, in

cluding Appendix A thereto, be and the

same is hereby changed, altered and

amended as follows: (a) Students in grades

9, 10, 11 and 12 residing in the Charles

Rice Elementary School attendance zone

are assigned to Lincoln High School and

(b) Students in grades 9,10, 11 and 12 re

siding in the Paul L. Dunbar Elementary

School attendance zone are assigned to

James Madison High School)

11- 1-76 — Transcript of Proceedings (3 vols) of Vol.

VII

11-15-76 — Transcript of Proceedings (3 vols) Vol.

VIII. No exhibits. (Held February 27,

1976)

11-19-76 — Transcript of Proceedings (3 vols of Vol.

IX). (No exhibits) Held March 3, 1976.

11

12

1- 5-77 — Transcript of Proceedings (Vol. X) held

March 5, 1976. No exhibits.

4-25-77 — Transcript of Proceedings of Hearing of

Defendants' Motion for Approval of Site

Acquisition, School Construction and

Facility Abandonment held February 24,

1977.

10-26-77 — Argument and Submission, United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

10-29-77 — Motion (of Curry, et al) to File Post Sub

mission Memorandum on the Issue of the

Law of the Case

4-21-78 — Opinion of the United States Court of Ap

peals for the Fifth Circuit in Nos. 76-1849,

77-1752 and 77-2335

4- 21-78 — judgments of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in each case

5- 5-78 — Petition for Rehearing (The Dallas Inde

pendent School District), United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

5- 5-78 — Petition for Rehearing En Banc of

Appellees-Cross Appellants Donald E.

Curry, Et Al, United States Court of Ap

peals for the Fifth Circuit

5-22-78 — United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit's Letter Advice to Counsel in

No. 76-1849 Denying Petition for Re

hearing and Rehearing En Banc

5-26-78 — Motion for Stay of Mandate (The Dallas

Independent School District), United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir

cuit

8-14-78 — Order of the United States Court of Ap

peals for the Fifth Circuit denying motion

of appellees, Dallas Independent School

District, et al., for stay of mandate.

13

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

DALLAS DIVISION

EDDIE MITCHELL TASBY, et al.,

Plaintiffs

versus No. CA 3-4211-C

DR. NOLAN ESTES, et al.,

Defendants

Filed: Aug. 25, 1975

ORDER

On this the 25 day of August, 1975, came on to be

heard the motions of Dr. E. Thomas Strom, et al., and

of the Metropolitan Branches of the Dallas NAACP

that they be permitted to intervene in the above styled

matter and this Court having heard evidence and argu

ment of counsel is of the opinion that they should be

granted;

14

It is therefore ORDERED that Dr. E. Thomas Strom,

et al., and the Metropolitan Branches of the NAACP be

permitted to file their respective Pleas of Intervention

and become parties in this cause.

Isl W. M. TAYLOR, ]R.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT

JUDGE

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

DALLAS DIVISION

(Number and Title Omitted)

Filed: April 30, 1976

PLAINTIFFS' BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR

ATTORNEYS' FEES AND CO STS

* *

[4] Finally, the plan adopted by the Court in its order

of March 10, 1976, together with Supplemental Opin

ion and Orders dated April 7, 1976 and April 15, 1976

adopt and/or incorporate almost every precept propos

ed by plaintiffs for student assignment and non

student assignment features of the remedy. The

DISD's contention that plaintiffs have not prevailed in

this litigation is simply constructed out of whole cloth.

* *

15

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

DALLAS DIVISION

(Number and Title Omitted)

Filed: Jul. 20, 1976

MEMORANDUM OPINION

* *

[3] The DISD suggests next that plaintiffs are not the

prevailing party in this litigation. The Court finds this

assertion untenable. Plaintiffs prevailed on the liability

issue when the Court held on July 16, 1971, that the

DISD was not operating a unitary school system. On

appeal to the Fifth Circuit from the Court's Order of

August 2, 1971, the United States Court of Appeals

sustained the plaintiffs' claims and rejected every con

tention of the DISD other than faculty assignment

ratios. Finally, the plan adopted by the Court on March

10, 1976, and Ordered to be implemented on April 7,

1976, and April 15, 1976, incorporated almost every

precept proposed by plaintiffs for both student assign

ment and non-student assignment remedies.

* *

16

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 76-1849

D. C. Docket No. CA3-4211-C

EDDIE MITCHELL TASBY and

PHILLIP WAYNE TASBY,

by their parent and next friend,

SAM TASBY, ET AL„

Plaintiff s-Appellants

Cross-Appellees,

METROPOLITAN BRANCHES OF THE DALLAS

N.A.A.C.P.,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors

Appellants-Cross Appellees,

versus

DR. NOLAN ESTES, ET AL„

Defendants-Appellees

Cross Appellants.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Texas

17

Before COLEMAN, TjOFLAT and FAY, Circuit

Judges.

Filed: Aug. 16, 1978

JUDGMENT

This cause came on to be heard on the transcript of

the record from the United States District Court for

the Northern District of Texas, and was argued by

counsel;

ON CONSIDERATION WHEREOF, It is now here

ordered and adjudged by this Court that the judgment

of the said District Court in this cause be, and the same

is hereby, affirmed in part and reversed in part; and

that this cause be, and the same is hereby remanded to

the said District Court in accordance with the opinion

of this Court;

It is further ordered that defendants-appellees pay

the appellants' costs and appellants pay the costs of

appellee, Highland Park; all other parties are to bear

their own costs.

April 21, 1978

ISSUED AS MANDATE: AUG 15, 1978

18

A true copy

Test: EDWARD W. WADSWORTH

Clerk, U.S. Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit

Isl KIM B. DAVIS

Deputy

Aug. 15, 1978

New Orleans, Louisiana

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

(Number and Title Omitted)

Filed: Aug. 14, 1978

ORDER:

The motion of APPELLEES, DALLAS INDEPEN

DENT SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET AL. for stay of the

issuance of the mandate pending petition for writ of

certiorari is DENIED.

Isl GERALD B. TJOFLAT

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT

JUDGE

19

Quotation of language prepared by Petitioners Brinegar, et al.

"Memorandum Order filed July 16, 1971, is

printed as Appendix A to Petitioners

Brinegar's Petition for Writ of Certiorari to

the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit.

"Opinion of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit dated April 21,

1978, is printed as Appendix C to the Petition

of Nolan Estes, et al's Petition for Writ of Cer

tiorari (pages 130a-146a)."

Quotation of language prepared by Petitioners Curry, et al.

"The opinions, orders and judgment of the

District Court are set forth in Appendix "B" to

the Petition for Certiorari of Nolan Estes, et

al. (pages 4a-129a) and are reported in part at

412 F.Supp. 1192. The opinion of the Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit is set forth in

Appendix "C " to the Petition of Nolan Estes,

et al. (pages 130a-146a) and is reported at 572

F.2d 1010.

"The prior opinions, orders and judgment of

the District Court which are relevant to the

issues now presented are found at 342 F.Supp.

943 and consist of the following:

20

(a) Memorandum Opinion (July 16,

1971);

(b) Memorandum Opinion on Final

Desegregation Order (August 17,

1971);

(c) Supplemental Opinion Regarding

Partial Stay of Desegregation Order

(August 17, 1971)."

Quotation of language prepared by Respondents Tasby, et al.

"The opinion of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in Tasby v. Estes, on

appeal from the July 16, 1971 orders of the

trial court, is found at 517 F.2d 92 (5th Cir.

1975)."

Quotation of language prepared by Respondents Tasby, et al.

"That a Petition for Writ of Certiorari was

filed by Petitioners Estes, et al., from the opin

ion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit cited immediately above."

Quotation of language prepared by Respondents Tasby, et al.

That Certiorari was denied by the Supreme

Court of the United States in Estes, et al. v.

Tasby, et al., and such denial is found at 423 U.S.

939 (1975)."

21

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

DALLAS DIVISION

EDDIE MITCHELL TASBY, ET AL

versus No. CA-3-4211-C

DR. NOLAN ESTES, ET AL

TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS

VOLUME I

Filed: August 9, 1976

[60] DR. NOLAN ESTES,

one of the Defendants, being duly sworn, testified as

follows:

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. WH1THAM:

[62] Q Now, with respect to those figures then in

the intervening months between the August figures

and the [63] December figures you lost what percent of

your Anglo students?

A There was a loss of one percent in Anglo

students between the August enrollment figure date

and the December 1st date.

Q And with respect to the difference in student

percentages between the August and December dates

with respect to the black student population, what

change occurred?

A There was more than a one and a half of one per

cent increase in black population between August and

December.

Q And with respect to the Mexican-American pop

ulation, did it change?

A There was four-tenths increase between the

August and the December dates for Mexican-

Americans.

Q Now, Dr. Estes, is Defendant's Exhibit Number

10 a copy of the Board of Education's Plan submitted

pursuant to the Court's request?

A Yes, sir, it is.

Q And is Defendant's Exhibit Number 11 a copy of

the Board's Plan submitted to the Court pursuant to

the Court's request only reflecting the calculations bas

ed on the new student population figures we have dis

cussed?

A Yes, sir, it is.

[64] MR. WHITHAM:

Judge, for the record we will introduce in evidence or

offer in evidence Defendant's Exhibits 10 and 11.

THE COURT:

They are admitted.

2 2

Q Dr. Estes, again, directing your attention to

paragraph 1.2 of the Board's Plan.

A Yes.

MR. WHITHAM:

For the record, Judge, I would like to have it so I don't

search for the exhibit each time, can it be understood if

we now refer to the Board's Plan we are making ref

erence to Defendant's Exhibit Number 11 for point of

reference in the record?

THE COURT:

Yes.

Q Directing your attention again to the Board's

Plan, Dr. Estes, would you please look for the illustra

tion of the percentages for the first grade? Do you

remember where the first grade is located?

A Yes, sir.

Q And you have what percent of Anglo first

graders in the District?

A At the first grade level we have 36.7 percent

Anglos in the School District.

Q What percent of kindergarten students do you

have in the District that are Anglo?

[65] A 34.8 percent kindergarteners are Anglos.

* *

[66] Q By the time they reach the eleventh and

twelfth grades many times they have passed the com

pulsory [67] attendance age of going to school anyway?

A The largest dropout rate between the ninth and

eleventh grades is when students reach the compulsory

attendance age.

Q Now, in your mind, as an expert and adminis

trator of the Dallas Independent School District and

elsewhere have you been able to arrive in your staff at a

projection as to what the total enrollment by race

would be in the Dallas Independent School District in

the year 1980 based on your experience as a school ad

ministrator in Dallas?

A Yes, sir, we make annual projections.

Q What is the projection of the ethnic composition

of the Dallas Independent School District in 1980?

A Based on our projections which uses, of course,

enrollment for the past five years, as well as other fac

tors, we estimate that the percentage of Anglo enroll

ment in 1980 will be 26 percent of the total school pop

ulation as opposed, of course, to the 41 percent at the

present time.

Q All right. What will be your projected black

enrollment in 1980?

A Our black enrollment in 1980 will be 57 percent

as opposed to 44.5 percent at the present time.

Q What would be your projected Mexican-

American [68] enrollment in 1980?

A Based on our projection the Mexican-American

would represent 18 percent of our total enrollment in

1980 as opposed to 13.4 percent at the present time.

Q Dr. Estes, let us, before we go further with the

Plan, in order that the parties might know and the

Court, could you give me your experience as a school

24

man and school administrator since you became

employed in the school business and please begin with

your first employment in the school business and bring

me up-to-date.

A My first employment was in 1950, '49 and '50

when I joined the staff of the Bruni Independent School

District as a high school science and math teacher. I

moved from there into the Service, and after receiving

a master's degree at the University of Texas joined the

staff at Waco.

Q You have a master's degree in what, Dr. Estes?

A In school administration.

I was in the Waco Independent School District as an

elementary teacher and then later as a principal.

In 1959 I went to Chatanooga, Tennessee as the

assistant superintendent for instruction.

In 1962 I went to St. Louis County, Riverview Gar

dens, as superintendent of the schools.

* * * *

[7 1 ] Q Dr. Estes, I will hand you what has been

marked for identification as Defendant's Exhibit

Number 13 and I will ask you if you can identify that as

an exhibit representing historical enrollment in the

Dallas Independent School District for the years given?

Can you identify that exhibit?

A Yes, sir.

MR. WHITHAM:

Your Honor, we will offer in evidence Defendant's

Exhibit Number 13.

25

26

THE COURT:

It's admitted.

Q Dr. Estes, please look at Defendant's Exhibit 13,

in order to help the Court and the parties perhaps

follow the calculations shown thereon, you have begun

with the school year '69-'70, have you not, and ended

with the school year 1975 as of October?

A Yes, sir.

Q That represents how many school years?

A That represents five school years.

Q Now, in making the calculations shown on the

exhibit I noticed that there has been a subtraction of

kindergarten students from each total figure shown,

do you see that?

A Yes, sir.

[76] Q And does Defendant's Exhibit Number 1 en

titled Racial Composition reflect the racial composition

on a map of the student population in the Dallas In

dependent School District as believed between black

and white students?

A Yes, sir.

Q With respect to the color code, the orange color

represents the location of black students in the year

1960?

A That's correct.

Q The yellow colored area on Defendant's Exhibit

Number 1 represents the location of white students in

1960?

27

A That is correct.

Q Now, that far back separate figures were not

kept with respect to Anglos as distinguished from

Mexican-American students, were they not?

A That's right.

Q Do you know of your own knowledge the ap

proximate composition of the Mexican-American stu

dent body in that year?

A The only difference in that map would be what

[77] we call Little Mexico or Short North Dallas around

the Travis Elementary School and one section around

Juarez and Douglass in West Dallas.

Q To that extent, the Mexican-American popula

tion would be shown in the yellow area on the map?

A That's correct.

MR. WHITHAM:

Am I free to move up here, Your Honor?

THE COURT:

Oh yes, sure.

Q Did I also ask you, Dr. Estes, to cause to be

prepared that would reflect the current residential

patterns of the students within the Dallas Independent

School District?

A Yes, sir.

Q And is that shown on Defendant's Exhibit

Number 2?

A It is.

Q And by students, we're talking about those

enrolled in the school, not those of school age who

might reside within the Dallas Independent School Dis

trict?

A That's right.

Q Now, with respect to the color codes shown on

Defendant's Exhibit Number 2, what student body

population is reflected by the area in yellow?

A The only remaining predominantly white [78]

population.

Q What student body population is reflected in the

area colored pink?

A That is a naturally integrated area representing

minority and Anglo.

Q And what is the student body population

reflected in the dark orange color shown on Defen

dant's Exhibit 2?

A The dark orange represents predominantly

Mexican-American or black enrollment.

Q Now, when we get to parts of further explana

tion of the School District's Plan and we happen to

refer to those parts of the Plan and I believe it's part

three on the integrated map, if I follow my index cor

rectly. We have referenced generally to the area shown

in pink on Defendant's Exhibit 2, is that correct?

A That is correct. I believe it's area four, the

naturally integrated areas.

Q The naturally integrated areas, I'm sorry.

In further testimony you give with respect to the

School District's Plan, when we talk about the pairing

and clustering of the remaining Anglo students or the

predominantly Anglo areas with certain minority

areas, what area or color code on the map has ref

erence to the location of those Anglo students?

28

29

[79] A Two areas, the remaining white population

is reflected by the yellow colored area —

Q Let me stop you right there. Then in that part of

the School District's Plan pairing the predominantly

Anglo area, this map and its yellow area shows the loca

tion of those Anglo students?

A Yes, that's right.

Q When there is a pairing of the Anglo students

under the Board's Plan with certain minority areas of

the School District, those minority areas paired with

the yellow area are found in various locations within

the dark orange area, is that correct?

A Yes. You skip over the naturally integrated areas

to the orange areas.

Q All right. So that when you pair the remaining

Anglos with certain minorities you have in effect pair

ed students who are Anglo in the yellow area with cer

tain minority students in the —

A Predominantly minority area.

Q — predominantly minority areas shown in dark

orange and you've skipped over the naturally in

tegrated area shown in pink that lies between them —

A That's correct.

Q — is that correct?

Now, when we get to that part of the [80] School Dis

trict's Plan dealing with those minority schools that

will remain one race schools, those remaining one race

schools will be found in varying parts of the color code

orange on Defendant's Exhibit Number 2, is that cor

rect?

30

A That's correct.

Q Did I ask you to cause to be prepared a map —

THE COURT:

Let me ask a question with reference to — Dr. Estes,

to Exhibit Number 1, Map Number 1: Do you have the

census figures for that year nineteen —

THE WITNESS:

Yes, sir, we have the scholastic census for that year.

THE COURT:

Do you know approximately what it is?

THE WITNESS:

No. Offhand I don't have that information. We can

get that, however.

THE COURT:

All right, go ahead.

Q Did I ask you to cause to be prepared a map that

would reflect the growth for a three-year period

broken down by 1960, 1965 and 1970 of the growing

black scholastic population within the Dallas Indepen

dent School District?

A Yes, sir.

Q Then did I ask you also to cause to be made on

[81] that same map a showing, graphically, of areas to

day that in 1965 were composed of at least twenty-five

percent black students?

31

A Yes, sir.

Q And did I also ask you to show on that map the

areas in 1975 that are at least twenty-five percent

Mexican-American in the Dallas Independent School

District's scholastic population?

A Yes, sir.

Q And did I also ask you to show on that map the

area that the School District finds to be at least twenty-

five percent minority combined, that is twenty-five

percent of either black or Mexican-American or both?

A Yes, sir.

Q Now, with respect — is all of that reflected on

Defendant's Exhibit Number 3?

A Yes, sir, it is.

Q Now, in using the figures we there talk about —

again, we are talking about students attending the

Dallas Independent School District, not total eligible

scholastics by reason of age or the right to attend

school.

A That's correct.

Q Now, with respect to the black population on

Defendant's Exhibit Number 3, those areas shown as

green [82] on Defendant's Exhibit Number 3 represent

the location of the black population in 1960, is that cor

rect?

A Yes, sir, that's right.

* *

[85] MR. WHITHAM:

This is known as the John Field attendance area,

should you need to know that.

And which particular schools are served —

THE WITNESS:

That would be the John Ireland-Hawthorne area.

Q (Continuing by Mr. Whitham) So by looking at

this map you can show growth patterns of minority

areas as shown on Defendant's Exhibit 3 as they now

might be reflected in total color schemes on Defen

dant's Exhibit Number 2?

A That's correct.

MR. WHITHAM:

We offer in evidence Defendant's Exhibits 1, 2 and 3,

Your Honor.

THE COURT:

They're admitted.

MR. WHITHAM:

Your Honor, if I failed to do so, I offer in evidence

Defendant's Exhibit 13, the historical enrollment

pattern. Mr. Cloutman was kind enough to tell me I had

not offered that.

THE COURT:

All right. I thought it was admitted, but it is admitted

again if —

32

Q Now, Dr. Estes, with your testimony today

together with the historical enrollment patterns of the

School District, Exhibit 13 together with the maps,

Plaintiff's Exhibits 1, 2 and 3 (sic) that will contain the

evidence of the change in ethnic patterns within the

[86] Dallas Independent School District showing the

matter with which we are concerned?

A Yes, sir, over the past fifteen years.

33

* * * *

[103] Q And all that anyone would need to do is take

[104] the material compiled in the Board's Plan and

compare the numbers on Defendant's Exhibit 5 and

they would be able to tell what students from what

schools are to go to school together under the Board s

Plan?

A That's correct.

MR. WHITHAM:

Does the Court have any question about the num

bering system or the assignments?

THE COURT:

No.

Q Now, with respect to fourth and fifth graders in

the naturally integrated area, the yellow hatched area,

those students continue to attend their neighborhood

schools, do they not —

A Yes, sir.

Q — under the Board's Plan?

A Under the Board's Plan they would continue to

go to their neighborhood school as they do now.

Q So the Board s Plan does not contemplate

transporting children or reassigning them if they are

within the yellow hatched or naturally integrated area?

A Yes, the Board's Plan doesn't disturb any of the

naturally integrated areas in the city.

Q Therefore, if a child attends school in what is a

pink area on Defendant's Exhibit 2, that child is not in

volved in further transportation and the concept of the

neighborhood school is preserved in those parts [105]

of the School District colored in pink?

A Yes, sir, because they're already integrated.

Q All right —

THE COURT:

Then the neighborhood school concept is preserved

in grades K through 5?

THE WITNESS:

Through six.

THE COURT:

Six.

THE WITNESS:

Or seventh in some instances.

THE COURT:

I see.

MR. WHITE!AM:

If the Court will look in the School Board's Plan of

the integrated neighborhoods of part four, Your

3 4

Honor, you will see that some of those buildings

currently serve even K-7.

THE COURT:

I see.

MR. WHITHAM:

In that grade configuration, whatever it is, con

tinuous.

THE COURT:

I see.

MR. WHITHAM:

If that answers that question.

THE COURT:

I see.

Q Now, with respect to fourth and fifth graders in

the part of the Board's Plan known as part seven

described as a certain part of the predominantly

minority parts of the School District, you have ref

erence to an area shown on Defendant's Exhibit 5 and 6

that is green hatched and brown hatched, is that cor

rect?

[106] A Yes, sir, that's correct.

35

[218] CROSS EXAMINATION

BY MR. CLOUTMAN:

36

★ * *

[278] Q So you have thirty-two hundred and fifty

minority students you anticipate will be integrated on

what basically is a voluntary basis next year?

[279] A In the initial implementation of the Plan.

Q And you expect that to increase to ten thousand?

A We would expect that to increase considerably

over the next three years; as much as ten thousand,

yes.

Q So by my rough subtraction that leaves you with

roughly forty thousand minority students not involved

in any integrated atmosphere?

A That would be close to correct.

MR. CLOUTMAN:

Excuse me, Your Honor, one second.

THE COURT:

Okay.

Q (By Mr. Cloutman) Doctor, just for my own pur

poses and for comparison, can you or do you know the

Dallas Independent School District's ethnicity by pop

ulation as opposed to student enrollment?

A I don't. I'm assuming it's about twenty-five or

thirty percent black, ten to fifteen percent Chicano and

the remainder Anglo.

Q Would you estimate it would approximate the

population breakdown by ethnicity of the City of

Dallas?

A That's right.

MR. CLOUTMAN:

Thank you. I don't think we have any further

questions at this time, Your Honor.

37

* *

[399] RE-DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. WHITHAM:

* *

[404] Q Now, the Dallas Independent School Dis

trict from the maps in evidence appears to be some

thing less than a rectangle. Do you have any idea of its

dimensions from its furtherest northernmost point to

its furtherest [405] southernmost point?

A It goes to the County line in the north and all the

way to the County line in the southeast or ap

proximately there and this distance is approximately

thirty-five miles from the northwest to the south

eastern part of the district.

Q And do you know approximately how far it is

from what's called the southwest quadrant in Oak Cliff

just below Hulcy junior High School to the northern

most point near the Dallas County line?

A Yes, that's about twenty-five miles.

Q Do you know the approximately total square

miles in the Dallas Independent School District?

A Yes, sir. We occupy three hundred fifty-one

square miles within the nine hundred square mile

County.

Q Now, you do not have an actual population cen

sus of just the Dallas Independent School District, do

you?

A No, we do not.

Q Do you know the approximate population of the

City of Dallas as a total?

A As I remember, eight to nine hundred thousand

is the population of the City of Dallas.

Q And of that total do you know what percent you

serve as to that part of the Dallas Independent [406]

School District lying within the City of Dallas?

A I would estimate we serve eighty percent of the

students living in the City of Dallas and in our school

district.

Q The boundaries of the City of Dallas and the

Dallas Independent School District are not conter

minous are they?

A Unfortunately they are not conterminous.

Q Please turn to Defendants' Exhibit Number 12, if

you would, to page 1 and let's be sure we are together as

to certain confusion about the number of so-called one

race schools that will remain under the board's plan.

A All right.

Q As I look at page 2 of Defendants' Exhibit

Number 12 under the third column predominantly

38

minority schools, I see that there are forty-two atten

dance zones that will remain predominantly one race.

A That's correct.

Q Do you see that figure?

A Yes, sir.

Q We are agreed there will be forty-two atten

dance zones that remain one race under the board's

plan, is that correct?

A Correct.

39

* *

TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS

VOLUME II

(Number and Title Omitted)

Filed: August 9, 1976

■ k it

[2] KATHLYN GILLIAM,

called as a witness in behalf of the Plaintiffs, being duly

sworn, testified as follows:

[49] CROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. WHITHAM:

40

* * ★ ★

[54] Q You were just trying to give the Judge your

experiences, not the experiences of the Tri-ethnic

Committee?

A Correct.

Q Now, how many times have you run for the

board of education of the Dallas Independent School

District?

A I ran twice, once unsuccessfully.

Q And then following the establishment of single

member trustee districts you were elected, were you

not?

A Exactly.

Q And you have had for some time an interest and

concern for education in Dallas for its children, is that

correct?

A That's been my life's work as an adult.

Q And you have sought to carry out that work as a

member of the board of trustees, have you not?

A Correct.

Q And when you would seek the office of trustee in

elections, would you make it known to voters your con

cerns about education in the Dallas Independent School

District?

A Correct.

4 1

[57] Q Would like any of your rights to be a policy

[58] maker for the Dallas Independent School District

taken away from you?

A I would not, not only my rights as a board

member but any of my rights, my rights as a citizen.

Q Your rights as a board member?

A Yes.

Q You don't want anyone to take those away from

you, do you?

A Correct.

Q No one, is that correct?

A That's correct, I do not want my rights as a board

member or any other rights taken away from me.

Q You want to exercise fully your rights as a

trustee of the Dallas Independent School District?

A Right.

Q And are you satisfied that you will continue to

exercise your policy making obligations on the Dallas

Independent School District as your good conscience

dictates?

A Yes.

Q How is the board now composed racially? Could

you describe the racial composition of the board?

A Two blacks, one Mexican-American and six

Anglos.

Q Now, do you actively speak up when board [59]

policy is under consideration on behalf of black citizens

within the Dallas Independent School District?

A Not only do I speak up on behalf of black citizens

in the DISD, I speak up in terms of what I think is just

and fair and right.

Q All right. Who is the other black member of the

board?

A Dr. Emmett Conrad.

Q Does Dr. Emmett Conrad also speak up for the

black patrons of the DISD?

A Yes, and others, too.

Q Others, too?

A Yes.

Q Who is the Mexican-American member?

A Roberto Medrano.

Q Does he speak for the Mexican-American

patrons of the Dallas Independent School District?

A And others.

Q And others?

A Yes.

Q Do the white members of the board of education

speak up for their constituents and patrons of the

Dallas Independent School District?

A And others.

Q And others?

[60] A Yes.

Q On the board of education at this time there is a

good bit of give and take to resolve the issues of the day,

is there not?

A Quite a bit of conversation.

Q That s right. Now, not all views that any one

trustee ever advances at any given point always carries

the day, does it?

A 1 hat's the idea of democracy.

Q You win some and you lose some?

A Yes.

4 2

4 3

Q Right.

A Yes.

Q Now, to the extent that you win some and you

lose some that's how public bodies' policy making

decisions ultimately get carried out, is it not?

A That's correct.

Q In your judgment do you feel that you are as ac

tive and ardent a spokesman for the black position in

Dallas as anyone you can conceive at this time?

A Well, I would not like to compare myself to

anybody else.

Q Do you feel that you're an effective spokesman

for the black patrons of the Dallas Independent School

District?

[61] A I feel that I do my best.

* * k *

[257] JOSE A. CARDENAS,

the witness having been duly sworn by the Court,

testified on his oath as follows:

* * k

[326] CROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. MARTIN:

44

[333] THE WITNESS:

Counselor asked the question in deposition, would

fifty percent constitute a significant proportion? He is

interpreting my answer, which was " y e s ” , to mean that

fifty percent of the people in Dallas are satisfied, or the

minority people or the Mexican American people in

Dallas, or the ones l talked to are dissatisfied with the

School and fifty percent were not. No question was

asked that I can remember, and certainly not the one

that he has read on three occasions, what was the num

ber of people or the proportion of the people that were

satisfied and dissatisfied? The question was, would fif

ty percent of the people be statistically [334]

significant? And my answer was, yes. Now, he is inter

preting this to mean that I said fifty percent of the peo

ple were satisfied and fifty percent of the people were

dissatisfied and I will not admit to this, sir. Because in

what he has read, anyway, I did not make any state

ment as to the percentage of people dissatisfied and

satisfied. It was a question as to whether fifty percent

would be statistically significant.

MR. MARTIN:

We'll offer in evidence, Your Honor, pages 31, 32,

and 33. And to save time, I won't read them at this time,

but may they be considered to be a part of the record?

THE COURT:

Yes, they will.

Q (By Mr. Martin) Doctor, do you have any dif

ficulty in separating your own ethnicity from your

professional judgments and opinions?

A I would imagine so, sir. I think that any person is

completely schizophrenic who can separate one aspect

of his personality —

Q It would be a hard thing to do; is that right, sir?

A Yes sir.

Q Now, as I understand you here in your testimony

here this morning, based on your interviews of the

patrons, [335] based on your interviews of the School

District personnel, based on your visit to two schools —

two or three, and based on your examination of these

documents that have been discussed here you found

that the Bilingual Program here is relatively in

novative, with many desirable traits and accomplishing

desirable results; is that correct?

A Yes sir.

Q Were you a little surprised to find that?

A No sir.

Q When you consider what you have thought of

such programs and the dealing with the uniqueness of

minority students by school people, what you have

thought of that in the past, does what you found here

seem a little inconsistent with your previous

judgments about that matter in general?

A No sir.

Q Dr. Cardenas, I will refer you to — you are the

same Dr. Cardenas that submitted an education plan

for the Denver Public Schools that was filed in the Keys

case?

46

A Yes sir.

Q May I refer you to some statements in that

report prepared by you? On page 6 of it — I'll show you

any of these if you can't recall what you said — you said:

The dismal failure of our schools in the education of

minority children can be attributed to the inadequacy

of the [336] instructional programs.

Do you still believe that?

A Yes sir.

Q And at another place in your proposal, you had

this to say: That the incompatability between minority

children and most school systems can be summarized in

three generalizations: One, most school personnel

know nothing about the cultural characteristics of the

minority school population.

Right, so far?

A Yes sir.

Q Two, that few school personnel who are aware

of these cultural characteristics seldom do anything

about it.

Do you recall that and that was your opinion?

A Yes sir.

Q Number three, on those rare occasions when the

school does attempt to do something concerning the

culture of minority groups, it always does the wrong

thing.

Do you still believe that?

A Yes sir.

Q Do you think we're doing the wrong thing here

in Dallas?

A I think you're doing some things right in Dallas. I

don't think it's universal and applicable to all of the

minority population in Dallas.

[337] Q And you came to Dallas to make this in

vestigation with these things in mind: You thought

that school personnel — the few school personnel who

are aware of these cultural characteristics seldom do

anything about it and that on those rare occasions

when they do attempt to do something, they always do

the wrong thing; you thought that when you came to

Dallas?

A Yes sir.

Q And you weren't surprised when you found a

pretty good program here?

A I wasn't surprised when I found some elements

of a good program here, no sir.

Q Your main criticism, as I understand you, is there

is just not enough of it? What you saw is good, but

there's not enough of it; is that right?

A It's not involving enough kids, there's not

enough of it.

THE COURT:

I didn't get your answer.

THE WITNESS:

It is not involving enough children and it is not exten

sive enough.

Q (By Mr. Martin) What there is of it is good?

A Yes sir.

Q Now, you spoke of the underachievement or

under-performance —

47

48

MR. MARTIN:

Just a few more minutes, Judge.

[338] Q (By Mr. Martin) — the underachievement

or underperformance of minority children in Dallas.

A Yes sir.

Q Now, in making that judgment about under

achievement and underperformance, I would like to

ask, compared to what?

A To the white Anglo population of the Dallas In

dependent School District.

Q Now, can you tell me this —

A And to national norms.

Q And to national norms, that's what I wanted to

ask you about.

Do you believe that the minority children in the

Dallas School District, that the performance of minori

ty children in the Dallas School District is on a par with

the performance of minority children on a national

basis?

A Yes sir.

Q Yes sir.

You spoke a few minutes ago about dropouts and the

reason for dropouts. Certainly the kind of programs in

the schools doesn't serve as the only reason for drop

outs, does it?

A Sir?

Q The kinds of programs that schools offer, that is

not the sole reason for dropouts?

A No sir.

* *

4 9

[340] Q Yes sir.

A But school has a lot to do with it.

Q Does home have something to do with it?

A Both home and school have something to do with

it.

Q The problems attendant to arriving at school,

the sheer getting there, does that have something to do

with whether a child drops out of school?

A Yes sir.

Q Does the fact that a child feels uncomfortable in

a given student body have anything to do with whether

he might drop out or not?

A Yes sir.

Q Does his problems with law enforcement have

anything to do with whether he might drop out of

school?

A It may.

Q Does his desire to go to work at a particular job

he has in view have anything to do with whether a child

drops out of school?

A It may.

Q Yes sir.

To sum up, Dr. Cardenas, then we're agreed that

what's being done here is good but you're saying

there's just not enough of it; is that the substance of it ?

A Yes sir.

MR. MARTIN:

Thank you, sir.

* ★

50

TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS

VOLUME III

(Number and Title Omitted)

Filed: August 9, 1976

[2] CHARLES V. WILLIE,

called as a witness in behalf of the Plaintiffs, being duly

sworn, testified as follows:

•k

[126] CROSS EXAMINATION

BY MR. MOW:

* * * *

[134] Q What transportation patterns did you con

sider?

A I did not consider transportation particularly. I

considered them in general and the general considera

tion is that transportation is an essential component of

urbanization. People drive long distances to work, they

drive long distances to worship. They drive long dis

tances for recreation. Therefore, I could not see any

reason why traveling would be contraindicative for

getting a quality education.

5 1

Q Did you consider how the roads are laid out

within Dallas and how much time it takes to get from

one part of town to another?

A In my driving around the city I did make obser

vations on the road systems in Dallas in which I found

to be exceedingly good compared with the road system

in Boston.

Q Did you make any time studies as to how long it

would take to get from certain areas of the city to cer

tain other areas?

A Yes, I made time studies of how long it would

take to go from the tip end of North Dallas to Oak Cliff

and I found that to be an exceedingly long distance. But,

I don't think that the School Districts have to be laid out

that way.

* *

[148] CROSS EXAMINATION

BY MR. DONOHOE:

* *

[151] Q That's all I was trying to get at.

A Yes.

Q All right. Now, Dr. Willie, also in the course of

your testimony you talked about a learning experience

or learning experiences and life experiences. I take it

that you would agree that it is a useful learning ex

perience for middle-class, or if I can use it, I think it's a

sociologist term, the higher socioeconomic people

would have the experience of going to school and living

with people in the lower socioeconomic groups, is that a

correct statement?

A The correct statement would be that people in

any class level ought to experience all sorts and con

ditions of people which characterize the metropolitan

area in which they reside.

Q So that works both ways is what you're saying?

A That's right, it works both ways.

Q You also in the course — well, let me finish it.

You would agree then it is — assuming a substantial

middle-class, if you will, disregard whether they are

black or white or Mexican-American, it would be useful

for these people, all people to experience each other's

experiences in the course of their educational career

and that would mean that middle-class people, middle-

class experience would be useful to lower socio

economic [152] class people, is that correct, regardless

of race?

A That's correct and vice versa.

Q All right. Let me ask another question on it. I

wasn't clear on this. In your testimony were you

proposing that assuming whites were to leave the sys

tem, I gather it was your testimony that that should not

be or that no attention should be paid to that in terms of

the desegregation plan, the concept or phenomenon of

white flight or out migration of whites should be dis

regarded?

A My position was that where people live is within

the realm of private behavior and is not a matter before

the Court.

52

Q Ail right. And I believe you distinguished, if 1 un

derstood you correctly, two forms of private decisions,

one would be out migration that would be physically

moving and another would be just a decision to go to a

private institution?

A That would be in the realm of private decisions.

Q All right. Now, if that phenomenon were to oc

cur after a Court-ordered plan based on certain percen

tages of blacks, whites and Mexican-Americans and

there should be a severe reduction of the white popula

tion, just assume with me for a moment, would it be

your view that at a subsequent time the plan should be

[153] redrawn so as to create this mix of populations?

A That's a conjecture I cannot respond to because

other possibilities are also there, that whites will move

back to the city.

Q Well, assume they didn't.

A I can't answer that question on the basis of that

assumption.

Q But you're not in a position to testify that you

would continually revise the plan at some later date

based on the out migration of blacks, Mexican-

Americans and whites?

A That's a conjecture that I can't answer. I have no

idea what the actual facts might be.

Q So a change in percentage in the proportionate

mix of a school population would not be something that

would be looked at in that monitoring system that you

were talking about in terms of revising the plan?

A It could be a responsibility that the Court would

ask the monitoring system to take into consideration.

5 3

Q In an effort to make sure that all children ex

perience this we could conceivably find a redrawing of

districts at some future time on some reasonable basis?

A Well, the reason why I have difficulty answering

[154] is a basic philosophical answer but I think it's

helpful because eventually the categories which are

now the subject of the suit may become irrelevant, that

is race and ethnicity could eventually become an irrele

vant category.

Q Because the school becomes a unitary school

system?

A Because the school becomes a unitary school

system, the population becomes unitary and these

categories would no longer be significant categories.

That is a possibility.

Q For example, the white population might be

reduced to fifteen percent and it would no longer be

significant?

A No. The point I am making is being white, being

Anglo may essentially become a nonsignificant char

acteristic of a human being.

Q Now, changing the line of thought, I think I un

derstand, Dr. Willie, in the drafting of a desegregation

plan do you believe that the Court should take into con

sideration such elements as the concept of the city and

its planners in dealing with given areas of the city,

should that be in any way relevant to the preparation of

a desegregation plan?

A Partially.

[155] Q All right. Now, 1 think you anticipate me, in

the area of the city that I am concerned with there is a

54

serious effort, and this is not in evidence, but assume

with me for the moment that there is a serious effort

being made by the city with the support of the City

Council and with the support, l believe, of most leaders

of communities of all races to reverse or somehow han

dle the problem of what sometimes is called "urban

blight", aging of neighborhoods and so forth. Would

that in any way affect your thinking about how to set

up a desegregation plan? Would that activity in any

way affect your thinking?

A It would depend upon whether or not that activi

ty interfered with the constitutional requirement for

operating a unitary school system.

Q You would, of course, put a limitation on the law

is what you're saying, but let's suppose for a second

that the people — well, do you agree with me that the

school system is a community? I believe the sociologists

say that it is the system that reflects the attitude of the

people, where they decide to live in given areas such as

the police department and road systems and similar

type of systems, would you agree with me?

A Yes, the school system is an institution which

[156] is sanctioned by the community to fulfil! com

munity goals.

Q Now, suppose that the decision is made by the

city planners that the retainage of middle-class people

in a given area with the skills they have in government

and all kinds of skills is a benefit to making a multi

racial multiclass socioeconomic status area, would you

disagree with that as a city planning concept?

A I would not disagree with that so long as that

55

5 6

decision did not encroach upon the rights and

prerogatives of people who are not middle-class.

Q I understand. You would also agree that the

retainage of some middle-class participation because of

their skills they could lend in turn to other groups and

of course the other groups contribute to the middle-

class, we understand that would be a valid planning

goal for the City Planning Department trying to

reverse deterioration of a neighborhood.

A My basic belief is that a valid city planning goal is

to have diversified communities consisting of a range

of social classes and range of races and range of age

categories.

Q Now, if an expert in this area were to say that he

needed to provide — he needed to assure that the

middle-class people do not leave the area if he could you

would not, in order to keep their skills in [157] the area,

this would not be something that you would object to,

leaving aside the constitutional question, is that cor

rect?

A To the extent the middle-class people would con

tribute to the diversity which is the overriding goal I

would not object to it.

Q Maybe I could put it in simple terms. Desegrega