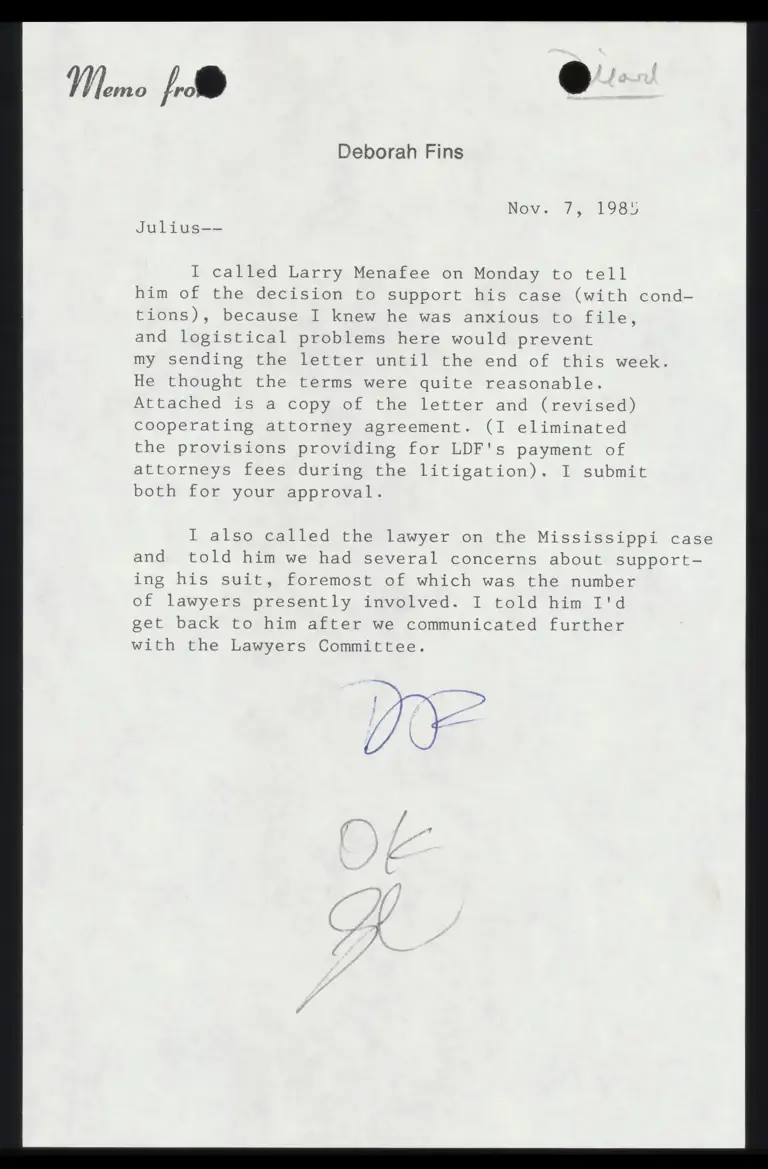

Memo from Fins to Chambers

Correspondence

November 7, 1985

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Memo from Fins to Chambers, 1985. 450af793-b8d8-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3cf4687d-2b11-4b3d-bc4c-59ab3f464a7c/memo-from-fins-to-chambers. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Mm. mo Iz J

Deborah Fins

Zz, 198%

Julius—~

I called Larry Menafee on Monday to tell

him of the decision to support his case (with cond-

tions), because I knew he was anxious to file,

and logistical problems here would prevent

my sending the letter until the end of this week.

He thought the terms were quite reasonable.

Attached is a copy of the letter and (revised)

cooperating attorney agreement. (I eliminated

the provisions providing for LDF's payment of

attorneys fees during the litigation). I submit

both for your approval.

I also called the lawyer on the Mississippi case

and. told him we had several concerns about support-

ing his suit, foremost of which was the number

of lawyers presently involved. I told him I'd

get back to him after we communicated further

with the Lawyers Committee.