Order for Joint Stipulation

Public Court Documents

May 11, 1995

3 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Order for Joint Stipulation, 1995. 66302f5b-a346-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3d3e986f-5710-4c34-ad37-427623cad443/order-for-joint-stipulation. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

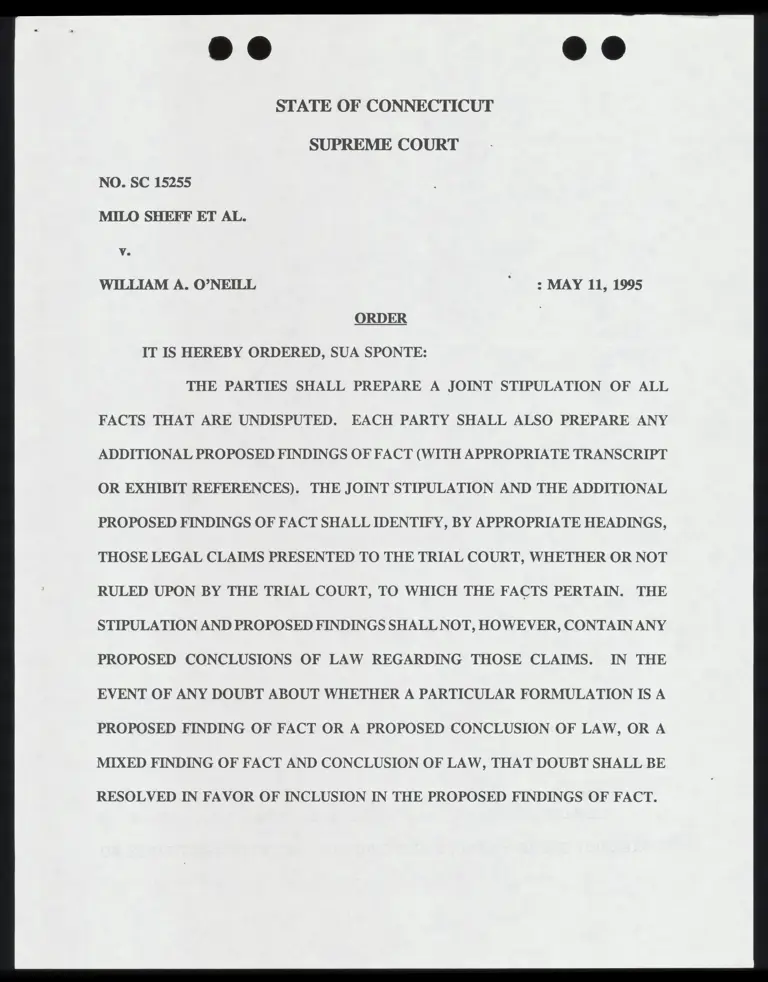

STATE OF CONNECTICUT

SUPREME COURT

NO. SC 15255

MILO SHEFF ET AL.

Ve.

WILLIAM A. O’NEILL ©: MAY 11, 1995

ORDER

IT IS HEREBY ORDERED, SUA SPONTE:

THE PARTIES SHALL PREPARE A JOINT STIPULATION OF ALL

FACTS THAT ARE UNDISPUTED. EACH PARTY SHALL ALSO PREPARE ANY

ADDITIONAL PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT (WITH APPROPRIATE TRANSCRIPT

OR EXHIBIT REFERENCES). THE JOINT STIPULATION AND THE ADDITIONAL

PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT SHALL IDENTIFY, BY APPROPRIATE HEADINGS,

THOSE LEGAL CLAIMS PRESENTED TO THE TRIAL COURT, WHETHER OR NOT

RULED UPON BY THE TRIAL COURT, TO WHICH THE FACTS PERTAIN. THE

STIPULATION AND PROPOSED FINDINGS SHALLNOT, HOWEVER, CONTAIN ANY

PROPOSED CONCLUSIONS OF LAW REGARDING THOSE CLAIMS. IN THE

EVENT OF ANY DOUBT ABOUT WHETHER A PARTICULAR FORMULATION IS A

PROPOSED FINDING OF FACT OR A PROPOSED CONCLUSION OF LAW, OR A

MIXED FINDING OF FACT AND CONCLUSION OF LAW, THAT DOUBT SHALL BE

RESOLVED IN FAVOR OF INCLUSION IN THE PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT.

AN ORIGINAL AND THREE COPIES OF THE JOINT STIPULATION

AND ANY PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT SHALL BE FILED WITH THE

APPELLATE CLERK ON OR BEFORE MAY 25, 1995, AND SHALL BE PROMPTLY

DELIVERED BY THE APPELLATE CLERK TO THE TRIAL COURT, THE

HONORABLE HARRY HAMMER.

THE TRIAL COURT SHALL PROMPTLY REVIEW THE STIPULATION

OF FACTS AND PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT AND ANY OTHER FILINGS

RELATING TO FACTUAL ISSUES THAT THE TRIAL COURT MAY FIND HELPFUL.

THE TRIAL COURT SHALL FILE WITH THE APPELLATE CLERK, ON OR BEFORE

JUNE 15, 1995, ITS DECISION ON EACH OF THE DISPUTED FACTS DISCLOSED IN

THE PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT SUBMITTED BY THE PARTIES, WHETHER

OR NOT THOSE FACTS PERTAIN TO LEGAL CLAIMS RESOLVED BY THE TRIAL

COURT IN ITS MEMORANDUM OF DECISION DATED APRIL 12, 1995. FOR THESE

PURPOSES, A "DECISION" ON A DISPUTED FACT SHALL INCLUDE, WITHOUT

LIMITATION, A DECISION IN RESPONSE TO A CLAIM THAT THE PARTY

PROPOSING THE FACT DID NOT CARRY THE PARTY’S BURDEN OF PERSUASION

WITH RESPECT THERETO. THE TRIAL COURT SHALL NOT BE REQUIRED TO

FILE ANY CONCLUSIONS OF LAW REGARDING THE CLAIMS PRESENTED TO IT

BEYOND THOSE CONCLUSIONS ALREADY REACHED BY THE TRIAL COURT IN

ITS MEMORANDUM OF DECISION DATED APRIL 12, 1995. IN THE EVENT OF

ANY DOUBT ABOUT WHETHER A PARTICULAR PROPOSED FORMULATION IS

A FINDING OF FACT OR A CONCLUSION OF LAW, OR A MIXED FINDING OF

FACT AND CONCLUSION OF LAW, THE TRIAL COURT SHALL RESOLVE THE

DOUBT IN FAVOR OF INCLUSION IN ITS FINDINGS.

ANY MOTION FOR REVIEW OF THE TRIAL COURT'S FINDINGS SHALL BE

FILED WITH THIS COURT ON OR BEFORE JUNE 22, 1995.

THE PLAINTIFF-APPELLANTS’ BRIEF SHALL BE FILED ON OR BEFORE

JULY 27, 1995.

THE DEFENDANT-APPELLEES’ BRIEF SHALL BE EILED ON OR BEFORE

AUGUST 24, 1995.

THE PLAINTIFF-APPELLANTS’ REPLY BRIEF SHALL BE FILED ON OR

BEFORE SEPTEMBER 7, 1995.

BY THE COURT,

{ A er’ /

Xk bo 7 0 ar

MICHELE T. ancers 7

DEPUTY CHIEF CLERI

NOTICE SENT: 5/11/95

HON. HARRY HAMMER

MOLLER, HORTON & SHIELDS, P.C.

MARTHA STONE

PHILIP D. TEGELER

JOHN BRITTAIN

WILFRED RODRIGUEZ

RICHARD BLUMENTHAL, ATTORNEY GENERAL

BERNARD F. MCGOVERN, ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

MARTHA WATTS PRESTLEY, ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

MARIANNE ENGELMAN LADO

THEODORE SHAW

DENNIS D. PARKER

SANDRA DEL VALLE

CHRISTOPHER A. HANSEN