Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Brief Amicus Curiae Dekalb County Board of Education

Public Court Documents

June 1, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Brief Amicus Curiae Dekalb County Board of Education, 1990. 7041e74b-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3dbd87e7-be08-49df-916f-7fdf0aa0e199/oklahoma-city-public-schools-board-of-education-v-dowell-brief-amicus-curiae-dekalb-county-board-of-education. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

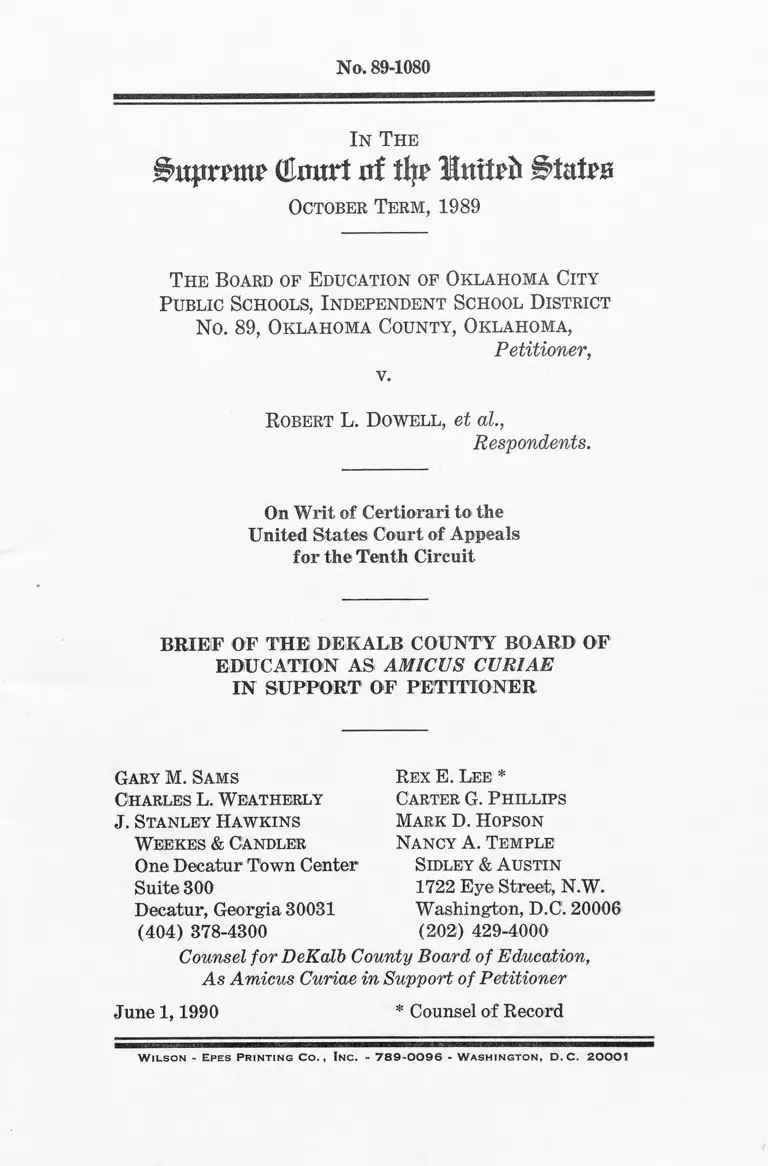

No. 89-1080

In T he

j^ujirpmp Qlmtrt ot tl|? IlntlTit §>taiP0

October Term, 1989

T he Board of Education of Oklahoma City

Public Schools, Independent School District

No. 89, Oklahoma County, Oklahoma,

Petitioner,

v.

Robert L. Dowell, et al,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the'

United States Court of Appeals

for the Tenth Circuit

BRIEF OF THE DEKALB COUNTY BOARD OF

EDUCATION AS: AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

Gary M. Sams

Charles L. Weatherly

J. Stanley Hawkins

Weekes & Candler

One Decatur Town Center

Suite 300

Decatur, Georgia 30031

(404) 378-4300

Rex E. Lee *

Carter G. Phillips

Mark D. Hopson

Nancy A. Temple

Sidley & Austin

1722 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 429-4000

Counsel for DeKalb County Board of Education,

As Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioner

June 1,1990 * Counsel of Record

W i l s o n - Ep e s P r i n t i n g C o . , In c . - 789-0096 - W a s h i n g t o n , D .C . 20001

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

Amicus curiae will address the following questions:

1. Whether the legal standards for modification of

antitrust decrees imposed upon private parties as enunci

ated in United States v. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106

(1932), that a decree may be modified only upon a show

ing of “ grievous harm” and that the dangers warranting

an injunction have become “ attenuated to a shadow” is

the proper rule for modification of a school desegregation

decree.

2. Whether under the Fourteenth Amendment a federal

court may refuse to dissolve a school desegregation decree

once local school authorities have established that the

school system has become unitary and that there is no

causal relationship between the prior constitutional viola

tion and any current conditions in the school system.

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ...... ...... ....................... -.... i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................... iv

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE __.................. .......... 1

STATEMENT .......... ....... ............. -............ -................. - 4

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ....................................... 10

ARGUMENT ........... 12

I. THE COURT1 BELOW ERRED IN INCORPO

RATING STANDARDS FROM ANTITRUST

LAW TO DETERMINE WHETHER TO

MODIFY OR VACATE AN INJUNCTION IN

A SCHOOL DESEGREGATION CASE.......... 12

II. THE DEMANDS OF THE EQUAL PROTEC

TION CLAUSE PROVIDE THE PROPER

RULE FOR DETERMINING WHETHER AN

INJUNCTIVE DECREE AGAINST LOCAL

SCHOOL AUTHORITIES SHOULD BE CON

TINUED ............ 20

A. A Federal Court’s Equitable Discretion To

Impose, Modify Or Vacate An Injunction

Structuring The Operations Of Local School

Districts Must Be Informed By The Respect

For Local Autonomy Embodied In Our Fed

eralism .................. .............. ....................... — 21

B. A Federal Court’s Authority To Continue A

School Desegregation Decree Terminates

When It Is Established That Intentional Seg

regation Has Ceased And Current Conditions

Are Not Attributable To Prior Segregative

Acts ............................................................. 24

CONCLUSION ................... ............ ............. ............... . 28

(iii)

Cases

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

25

Page

Allen V. Wright, 468 U.S. 737 (1984) .....................

Arlington Heights V. Metropolitan Housing Dev.

Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977)............... ................. . 24

Badgley V. Santacroce, 853 F.2d 50 (2d Cir. 1988).. 23

Brown V. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954)___ 19

Chrysler Corp. v. United States, 316 U.S. 556

(1942) ................................................................. . 14

Columbus Bd. of Educ. V. Penick, 443 U.S. 449

(1979) ..................... ....................... ............... ....... 18,19

Dayton Bd. of Educ. V. Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406

(1977) ............ 20,22

Dayton Bd. of Educ. V. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526

(1979) ............ 19

Doran V. Salem Inn, Inc., 422 U.S. 922 (1975)..... 23

Duran V. Elrod, 760 F.2d 756 (7th Cir. 1985)........ 23

Estes V. Metropolitan Branches of the Dallas

NAACP, 444 U.S. 437 (1980) .............. 28

Firefighters Local Union No. 178U V. Stotts, 467

U.S. 561 (1984) ........... ......... ......... ........... 14,15,18, 22

Ford Motor Co. V. EEOC, 458 U.S. 219 (1982).... . 14

General Bldg. Contractors Ass’n, Inc. V. Pennsyl

vania, 458 U.S. 375 (1982) ......................... .......... 20

Green V. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968).... 13, 18,

19

Hills V. Gatreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1976) .........13, 20, 21, 22

Keyes V. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, Colo., 413 U.S.

189 (1973) ................................................. 19,24,26

Kozlowski V. Coughlin, 871 F.2d 241 (2d Cir.

1989) ..........,............................................................ 23

Local No. 93, Int’l Ass’n of Firefighters V. City of

Cleveland, 478 U.S. 501 (1986) .......................... 14

Milliken V. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) ..............passim

Milliken V. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977)......19, 20, 23, 24

Missouri v. Jenkins, 58 U.S.L.W. 4480 (1990)...... 23

Money Store, Inc. V. Harriscorp Finance, Inc., 885

F.2d 369 (7th Cir. 1989)................................

Nelson V. Collins, 659 F.2d 420 (4th Cir. 1981)

23

23

V

New York State Ass’n for Retarded Children, Inc.

V. Carey, 706 F.2d 956 (2d Cir.), cert, denied,

464 U.S. 915 (1983) ..................................... ........ 23

Newman V. Graddick, 740 F.2d 1513 (11th Cir.

1984) .................... ............ ..................................... 23

Pasadena City Bd. of Educ. V. Spangler, 427 U.S.

424 (1976) .......... ............. ................... ................. passim

Pennsylvania V. Wheeling & Belmont Bridge Co.,

59 U.S. (18 How.) 421* (1856) ........................... . 14,15

Plyler v. Evatt, 846 F.2d 208 (4th Cir.), cert, de

nied, 109 S.Ct. 241 (1988) __________ ________ 23

Rizzo V. Goode, 423 U.S. 362 (1976) ....... .... .......... 21, 23

Ruiz V. Lynaugh, 811 F.2d 856 (5th Cir. 1987)___ 23

Simon V. Eastern Ky. Welfare Rights Org., 426

U.S. 26 (1976) .......... ................... .. ............... ...... 25

Spallone V. United States, 110 S.Ct. 625 (1990).... 23

Spangler V. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ., 611 F.2d

1239 (9th Cir. 1979) .......... ................... ......... ..... 23, 25

Stefanelli V. Minard, 342 U.S. 117 (1951)_______ 23

Swann V. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402

U.S. 1 (1971) _________ ___- ___ _____________ passim

Swift & Co. V. United States, 276 U.S. 311 (1928).. 16

System Fed’n No. 91 V. Wright, 364 U.S. 642

(1961) _______________________________ ______ 13, 14

Town of Hallie V. City of Eau Claire, 471 U.S. 34

(1985) ................... 18

Twelve John Does V. District of Columbia, 861 F.2d

295 (D.C. Cir. 1988) ..... ......... .... ...................... . 23

United States v. California Coop. Canneries, 279

U.S. 553 (1929) ................. ......... ....... ................ 16

United States V. Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U.S.

173 (1944)........................ - .......... ............ ........... 15,16

United States V. Glaxo Group, Ltd., 410 U.S. 52

(1973) .................. 15

United States V. Grinnell Corp., 384 U.S. 563

(1966) ............................ 15

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

United States V. Overton, 834 F.2d 1171 (5th Cir.

1987) ........ 26,27

United States V. Parke, Davis & Co., 362 U.S. 29

(I960) ..................................................................... 16

United States V. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106 (1932)..passim

United States V. United Shoe Machinery Cory., 391

U.S. 244 (1968) ......................................................passim

United States V. United States Gypsum Co., 340

U.S. 76 (1950) ................................... 16

Washington V. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ............. 24

Constitutional Provisions

U.S. Const, amend. X IV .........................................11, 20, 27

U.S. Const, amend. XIV, § 5 ..................................... 22

Statutes

20 U.S.C. § 1701 (a) ( 2 ) ................................. ........... 22

Fed. R. Civ. P. 60, Notes of Advisory Comm, on

1946 Amendment...................................... 18

Fed. R. Civ. P. 60 (b ) .................................................. 7,18

Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b) (5 ) ......................................... 13,17

In T he

Bnprmv ( t a r t of % It tt tr ft U t a t e

October Term, 1989

No. 89-1080

The Board of Education of Oklahoma City

Public Schools, Independent School District

No. 89, Oklahoma County, Oklahoma,

Petitioner,v.

Robert L. Dowell, et al.,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Tenth Circuit

BRIEF OF THE DEKALB COUNTY BOARD OF

EDUCATION AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT1 OF PETITIONER.

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The Board of Education of DeKalb County, Georgia,

which has been operating the DeKalb County School Sys

tem (“ DCSS” ) under federal court supervision for over

20 years, was recently ordered by a panel of the Eleventh

Circuit to “ consider pairing and clustering of schools,

drastic gerrymandering of school zones and . . . busing”

in order to alleviate racial imbalances in student assign

ment that had been caused solely by shifting demographic

(housing) patterns in the County occurring after an ad

mittedly effective remedy had been instituted. See Ap

pendix to Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, Freeman,

2

et al. v. Pitts, et al. (“DeKalb Pet. App.” ) , No. 89-1290,

at 23a. That order was issued despite the undisturbed

finding of the district court that, with respect to student

assignment:

The DCSS has become a system in which the char

acteristics of the [former] dual system have been

eradicated, or if they do exist, are not the result of

past or present intentional segregative conduct by

the defendants or their predecessors.

DeKalb Pet. App. 47a. Although the district court’s find

ing as to the effectiveness of the remedy was not reversed,

the Eleventh Circuit nevertheless overturned the district

court’s order ending federal court supervision of student

assignment policies on the ground that the district court

had applied too lenient a legal standard. See DeKalb

Pet. App. 24a. Thus, the Eleventh Circuit’s approach is

congruent with the Tenth Circuit’s decision under review

in at least one crucial respect: both courts have held that

a finding that the original constitutional violation has

been remedied is not dispositive in determining whether

to terminate federal intervention into the operations of

local school systems.1 Once the existence of a “ dual”

1 The Eleventh Circuit held that enforcement of the federal court

desegregation order would continue until the school system simul

taneously “ maintains at least three years of racial equality in six

categories: student assignment, faculty, staff, transportation, ex

tracurricular activities and facilities.” DeKalb Pet. App. 24a. Re

gardless o f the “ cause” of current racial imbalance or the effective

ness of the earlier remedial order in eradicating the original consti

tutional violation, the Eleventh Circuit made it clear that the DCSS

“ must take affirmative steps to gain and maintain a desegregated

student population.” Id. at 19a.

The Tenth Circuit in this case held that enforcement of the re

medial decree would continue until the school system demonstrates

“ ‘dramatic changes in conditions unforeseen at the time o f the decree

that both render the protections o f the decree unnecessary . . . and

impose extreme and unexpectedly oppressive hardships on the

obligor.’ ” Dowell II, Pet. App. 12a. (citation omitted). The Tenth

Circuit, like the Eleventh, finds an affirmative obligation to maintain

3

school system has been established, both courts reject the

need for a continuing causal link between the constitu

tional violation and the scope of an ongoing federally

supervised remedy, in favor of a rule that focuses solely

on the present condition (i.e., racial balance) of the

school system and requires amelioration of de facto con

ditions. See DeKalb Pet. App. 19a; Dowell v. Board of

Educ. of the Okla. City Pub. Schools (Dowell II), 890

F.2d 1483, 1490-91 (10th Cir. 1989), Pet. App. 13a-15a.

Although DeKalb County’s pending petition for certi

orari, which is being held pending disposition of this

case, presents somewhat different questions than those

presented here, DeKalb County has a significant interest

in the outcome of this case. See Petition for a W rit of

Certiorari, Freeman, et al. v. Pitts, et al. (“.DeKalb

Pet.” ), No. 89-1290, at i. Both this case and Freeman

V. Pitts focus on the fundamental questions of how to

measure both “ compliance” with desegregation orders and

at what point formerly de jure segregated school systems

have fulfilled their remedial obligations and should be

relieved of federal court supervision. The Tenth and

Eleventh Circuits both focus on achieving and main

taining the singleminded goal of complete racial balance

in the public schools. Yet, in doing so, both courts lose

sight of the fact that, in our federalist system, their

remedial authority is bounded by the requirements of

the Constitution and Our Federalism. Amicus DCSS sub

mits that once a constitutional violation is remedied and

the vestiges of the intentionally segregative dual sys

tem have been eliminated in any aspect of the school

system (e.g., student assignment), the proper federal

rule returns that aspect of the school system to local

control. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ. v. Spangler, 427

U.S. 424 (1976).

desegregated conditions (id. ait 18a) that justifies an ongoing federal

remedy even after the “ condition” or violation on which the re

medial order is based has been eliminated. Id. at 13a.

4

Racial integration is an important goal, and one that

the DCSS has been committed voluntarily to pursuing.

DeKalb Pet. 3-4. Nevertheless, day-to-day decisions on

the allocation of scarce local resources are impaired when

federal courts denigrate all other legitimate goals in

favor of maintaining arbitrary standards of “ racial bal

ance.” Both the Eleventh and Tenth Circuits have sub

stituted the “ goals” of a federal court decree for con

stitutional standards, thereby vastly expanding federal

authority over petitioner, over the DCSS and over hun

dreds of similarly situated local school authorities. Be

cause of the importance of the overlapping issues in this

case and in the pending DeKalb County petition (No.

89-1290) and because the Court’s decision in this case

will affect the existing status of federal court supervision

of the DCSS— either directly or indirectly— the DeKalb

County School Board is filing this brief as amicus curiae

in support of petitioner in this case.2

STATEMENT

Amicus DeKalb County School Board agrees with peti

tioner Board of Education of Oklahoma City’s (the

“ Board’s” ) statement of the case, but wishes to empha

size the following facts:

1. The case against petitioner was filed in 1961.

Doivell v. Board of Educ. of the Okla. City Pub. Schools

( “Dowell I” ), 795 F.2d 1516 (10th Cir.), cert, denied,

479 U.S. 938 (1986). In 1972, the “ district court ordered

the implementation” of the remedial scheme at issue,

which became known as the “ Finger Plan.” Id. at 1518.

That order utilized “ techniques of pairing, clustering, and

compulsory busing” to achieve racial balance in student

assignment. Dowell v. Board of Educ. of the Okla. City

Pub. Schools (“Dowell II” ), 890 F.2d 1483, 1486 (10th

Cir. 1989), Pet. App. 4a.

2 Pursuant to Rule 37 o f the Rules of this Court, the parties have

consented to the filing of this brief. Copies of the letters of consent

from the parties have been filed with the Clerk of the Court.

5

Several years later, the district court held an evi

dentiary hearing on the Board’s motion to close the case.

Pet. App. 2b. Based on the evidence presented at that

hearing, the district court in 1977 “ relinquished juris

diction over [the] case” because it was convinced that

the desegregation plan had been fully carried out “ and

that the School District had reached the goal of being a

desegregated non-racially operated and unitary school

system.” Dowell v. Board of Educ. of the Okla. City

Pub. Schools, 606 F. Supp. 1548, 1554 (W.D. Okla.

1985) ; see Dowell I, 795 F.2d at 1518.

During the next eight years the Board continued vol

untarily to operate the school system pursuant to the

requirements of the Finger Plan, with minor alterations,

even though the district court had declared the District

unitary and terminated the case. In the 1984-1985 school

year, however, the Board adopted a new student assign

ment plan (the “ reassignment plan” or “ plan” ), which

eliminated compulsory busing in grades 1 to 4 in favor of

neighborhood schools. Dowell II, Pet. App. 4a.3 In re

sponse, the plaintiffs moved the district court to “ reopen

the case,” arguing that the Board had wrongfully devi

ated from the Finger Plan.

After a hearing, the district court found that the

principles of res judicata precluded the plaintiffs from

challenging the 1977 finding that the school system had

“ reached the goal of being a desegregated non-racially

operated and unitary school system.” Dowell v. Board

3 The reassignment plan continued to maintain racial balance in

all other grades through mandatory busing. In addition, the plan

included a “ majority to minority” transfer option that permitted

elementary students (grades 1-4) in a school in which they were

in the majority race to transfer to a school in which they were

in the minority. See Dowell II, Pet. App. 4a-5a,. The district court

found that the change in the assignment plan was a response to

shifting housing patterns and the resultant increased busing burden

(in time and distance) on young black children. Dowell v. Board of

Educ. of the Okla. City Pub. Schools, 606 F. Supp. 1548, 1552 (W.D.

Okla. 1985).

6

of Educ. of the OMa. City Pub. Schools, 606 F. Supp.

at 1554, In addition, the district court found that the

school system in 1985 continued to operate and function

as a non-discriminatory unitary system (id. at 1555) and

that the reassignment plan was “ constitutional” — i.e.,

that the plan was adopted without any discriminatory

intent. Id. at 1556. Thus, the district court concluded

that there were no “ special circumstances” that war

ranted reopening the case. See Dowell I, 795 F.2d at

1518.

2. The court of appeals reversed, holding that the dis

trict court had erred in refusing to reopen the case for

the purpose of permitting the plaintiffs to “ enforce” the

provisions of the original remedial order. Dowell II, Pet.

App. 5a-6a. The key to the court of appeals’ decision

was its holding that the 1977 finding of unitariness did

not affect the continuing vitality of the “ mandatory in

junction” (i.e., the remedial order), and thus, “ the plain

tiffs . . . only have the burden of showing that the

court’s mandatory injunction has been violated.” Id. at

6a; see Dowell I, 795 F.2d at 1519. In so holding, the

court of appeals specifically rejected the United States’

argument that “ once a finding of unitariness is entered,

all authority over the affairs of a school district is re

turned to its governing board, and all prior court orders,

including any remedial busing order are terminated.”

Dowell I, 795 F.2d at 1520. In the Tenth Circuit’s view,

a finding of “ unitariness” relates only to the “ ministerial

function of ‘closing’ a case” and terminating active (i.e.,

day-to-day) supervision of school operations. Id. The

achievement of unitary status in no way affects a school

board’s continuing obligation strictly to comply with the

“prospective operation” of the federal court’s remedial

order. IdS 4

4 The court explained that this “ standard” for modifying or

terminating local school board obligations under federal desegre

gation decrees is the same legal standard “ applicable in all instances

where . . . the relief sought is escape from the impact of an injunc

tion.” Id. (citations omitted).

7

In sum, the Tenth Circuit found that proof that a

desegregation decree had successfully achieved its goal of

eliminating discrimination root and branch was not a

sufficient basis to dissolve an injunction. Instead, a school

board must show that retaining the injunction imposes

“ ‘hardship so extreme and unexpected’ as to make the

decree oppressive.” Dowell I, 795 F.2d at 1521. The

plaintiffs’ only “burden” was to demonstrate that the

School Board had deviated from the requirements of the

Finger Plan (Dowell I, 795 F.2d at 1523) ; according to

the court of appeals, such a showing “ constitutes the

‘special circumstances’ ” that justify “ reopening” the case

under Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b ). Dowell I, 795 F.2d at 1522.

The court of appeals thus remanded the case to the dis

trict court to test the School Board’s evidence against the

appropriate standard.

3. The district court noted initially that there had

been substantial changes in housing patterns that had

created the need to modify the Finger Plan. See Pet.

App. 19b. However, because residential segregation in

certain neighborhoods was the cause for “ the predomi

nately black elementary schools” under the new plan, the

court addressed whether those patterns of residential seg

regation could be linked to any unconstitutional action

on the part of the Board. Id. After reviewing all of the

evidence, the district court concluded that the Board had

“ taken absolutely no action which has caused or con

tributed to” segregated housing patterns (and, thus seg

regated neighborhood schools) in certain neighborhoods;

in fact, the Board’s actions over the past decade had

“ fostered the neighborhood integration which has occurred

in Oklahoma City.” Pet. App. 17b-18b.

On remand, the district court addressed the “ funda

mental issue” whether the “ School Board has shown a

substantial change in conditions warranting dissolution

or modification of the 1972 Order.” Pet. App. 5b. The

district court determined that the “ demographic changes”

at issue had created hardship and rendered aspects of

8

the Finger Plan “ oppressive” in a way that would justify

modification or dissolution of the injunction. Pet. App.

23b. The district court also held that the reassignment

plan, adopted in response to the changes in question, was

approved for legitimate, non-discriminatory reasons and

that the plan would not disturb the unitary status of the

school system— a status that had been maintained “ from

1977 to the present.” Pet. App. 24b-33b.

Finally, the district court addressed the issue whether

the 1972 desegregation decree, which adopted the Finger

Plan, should be modified or dissolved. Pet. App. 33b.

In considering whether changed conditions warranted

modification or dissolution of the decree, the court fo

cused on the issue of whether the purposes of the de

cree have been “ fully achieved.” Pet. App. 35b. The

district court stated that “ [t]he purpose of a desegrega

tion remedy is to ‘correct’ the condition that offends the

Constitution” (Pet. App. 36b), in particular, to “ dis

mantled] the dual school system.” Id. In this case, the

dual system had been dismantled and “ all vestiges of

prior state-imposed segregation had been, completely re

moved” from the school system by 1977. Pet. App. 38b,

36b. The plaintiffs’ focus on curing racial imbalance in

student assignment due to residential segregation—-for

which the Board was not responsible (Pet. App. 36b) —

was an attempt to achieve a remedy “ aimed at eliminat

ing a condition that does not violate the Constitution.”

Id. (citation omitted). Thus, the achievement of uni

tary status, together with the demographic shifts that

rendered continued conformity with the Finger Plan “ op

pressive,” was held to be sufficient to support dissolution

of the 1972 decree. Pet. App. 39b.

4. A divided panel of the court of appeals again re

versed. The court reiterated that modification or dissolu

tion of the decree requires a showing under the stan

dard in United States v. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106

(1932), that there has been a change in “ conditions”

that “ both render the protections of the decree: unneces-

9

sary to effectuate the rights of the beneficiary and im

pose extreme and unexpectedly oppressive hardships on

the obligor.” Dowell II, Pet. App. 12a. However, the

court held that the “ condition” that occurs as a result of

the injunction the achievement of unitary status)

“ cannot alone become the basis for altering the decree

. . . .” Id. at 13a.5 In addition to “ a finding of unitari

ness” , the Board would have to produce “ proof of a sub

stantial change in the circumstances which led to the is

suance of that decree.” Id. at 16a. On review of the

evidence, the court conceded that “ changed circumstances”

had been established {id. at 19a-20a) that supported

modification of the Finger Plan. Id. at 30a.

The court then turned to the issue of whether the

court below had erred in vacating the decree (rather

than modifying it). According to the court of appeals,

it appeared that the Board’s reassignment plan “has

the effect of making the District ‘un-unitary’ by reviving

the effects of past discrimination.” Dowell II, Pet. App.

31a. The court made clear that in judging the “ effective

ness [of the Board’s modification of the decree] in main

taining unitary status” {id. at 40a), it was measuring

the “plan” solely in terms of its effects on racial balance

in the school system and not in terms of its. relationship

to any unconstitutional conduct on the part of the Board:

we must focus not on whether the Plan is. nondis-

criminatory but on whether it solves the problems

created by the changed conditions in the District.

Id. at 41a. Here, the panel was “ troubled because the

evidence indicates the Board’s implementation of a ‘rac

ially neutral’ neighborhood assignment plan has had the

« According to the Tenth Circuit, unitariness.— defined as a “ state

of successful desegregation” .—simply does not “ mandate the later

dissolution of the decree without proof of a substantial change in

the circumstances which led to the issuance of that decree.” Pet.

App. 16a.

10

effect of reviving those conditions that necessitated a

remedy in the first instance.” Id. at 32a. Thus, the court

vacated the district court’s judgment dissolving the 1972

decree and remanded for consideration of modifications

to the Finger Plan that would “ maintain racially balanced

elementary schools within the framework of changed cir

cumstances that have occurred in the District.” Id. at

44a-45a.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

The Tenth Circuit assumes without justification that

the law applicable to prohibitory antitrust injunctions

governs the decision whether to terminate a federal

court’s remedial decree in a school desegregation case.

There can be no doubt that traditional equitable princi

ples inform a federal court’s approach in fashioning a

remedy for a constitutional violation by state authorities.

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S.

1, 15-16 (1971). But it does not follow from this that the

injunction standards applied to private antitrust defen

dants should be applied uncritically to a public school

board. See Pasadena City Bd. of Educ. v. Spangler, 427

U.S. 424 (1976); United States v. United Shoe Machinery

Corp., 391 U.S. 244, 248 (1968). Because the question

whether a specific injunction may be modified is anchored

to the substantive law justifying the imposition of the

original remedy, the proper federal rule for modifying

injunctive relief must refer to that substantive law.

The law governing the allocation of private economic

rights in antitrust decrees is inapposite to the determi

nation of the appropriate remedy imposed upon state

and local authorities for the purpose of curing the ef

fects of past equal protection violations. Antitrust de

crees rarely are subject to modification because they op

erate to prevent ongoing threatened violations. By con

trast, school desegregation decrees focus primarily on

11

the purpose of providing interim remedial relief. The

decrees remedying Fourteenth Amendment violations that

govern local educational policy are entered in contempla

tion of their termination once the school authorities have

cured the effects of the prior constitutional violation. At

that point, the federal court must relinquish control over

the school system by dissolving the injunction.

II.

A. A federal court has authority to order injunctive

relief in a school desegregation case only to the extent

of a proven violation of the Equal Protection Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment. In the development of this

substantive rule, this Court has long applied the tradi

tional equitable principle that “ the nature of the viola

tion determines the scope of the remedy.” Swann, 402

U.S. at 16; Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974)

(“Milliken I” ). The rationale for the limits upon the

federal judiciary’s powers to remedy effects from con

duct of state authorities is bounded by the Constitution

and Our Federalism. By requiring petitioners to per

petuate a judicially imposed racial balance in the school

system after a finding of unitariness, the court of ap

peals ignored the principle that the federal judiciary may

not regulate the activities of state and local authorities

absent a constitutional violation. Spangler, 427 U.S. at

434.

B. The substantive law-—the Equal Protection Clause

in this context— provides both the source and the limits

of a federal court’s power to impose remedial injunctive

relief upon state and local school authorities. According

to the traditional equitable principles, “ a decree may be

changed upon an appropriate showing.” United Shoe

Machinery Corp., 391 U.S. at 248. The district court

properly found that petitioner had made the appropriate

showing in this school desegregation case.

Under the substantive law that has evolved in school

desegregation jurisprudence, such decrees may be imple-

12

merited only to remedy segregative effects that are causally

linked to racially discriminatory actions of state or local

authorities. Spangler, 427 U.S. at 434. This Court’s, deci

sion in Spangler makes clear that a federal court must

dissolve an injunctive decree in a school desegregation

context once the purposes, of the decree have been achieved

and there has been a finding that there is no causal nexus

between any segregated condition in the school system and

the prior constitutional violation. By defining the goal of

the injunction to remedy conditions beyond the scope of

the violation and thus beyond a federal court’s power, the

court of appeals erred in refusing to dissolve the decree.

ARGUMENT

The Tenth Circuit’s holding is premised on its belief,

expressed in Dowell /, that a desegregation order, once

implemented, remains binding on a school system until

such time as the school system satisfies the “ difficult” and

“ severe” burden of demonstrating that because of a “ sub

stantial change in law or facts” the order has produced

“ ‘hardship so extreme and unexpected’ as to make the

decree oppressive.” Dowell /, 795 F.2d at 1521. In other

words, public school boards are to be treated no different

than meat packing companies. Such a rule will severely

impair current desegregation efforts, of many school

boards by removing the major incentive to achieve unitary

status. Moreover, if that is indeed the rule for school

desegregation cases, then the Tenth Circuit’s doctrine

signals a watershed change1— and a severe deterioration—

in federal-state relations,

I. THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN INCORPORATING

STANDARDS FROM ANTITRUST LAW TO DETER

MINE WHETHER TO MODIFY OR VACATE AN

INJUNCTION IN A SCHOOL DESEGREGATION

CASE.

As in any other case involving the modification or dis

solution of injunctive decrees, this ease requires, “ the

proper application of the federal law on injunctive rente-

13

dies.” Dowell 11, Pet. App. 3a. This Court has held that

a “ school desegregation case does not differ fundamentally

from other cases involving the framing of equitable reme

dies to repair the denial of a constitutional right.”

Swann, 402 U.S. at 15-16 (emphasis added); see also

Hills v. Gatreaux, 425 U.S. 284, 294 n .l l (1976); Milli-

ken I, 418 U.S. at 744.® For that reason, some of the

basic principles that cabin a federal court’s authority to

modify injunctive relief apply equally to any request to

modify a desegregation decree. But it does not follow that

the defendant’s status as a public entity is irrelevant to

the basic question of how long a decree must remain in

effect. As applied in the context of school desegregation

cases, the rules on federal injunctions do not require

decrees against local school authorities to exist in virtual

perpetuity. Since Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S.

430 (1968), it has been clear that such decrees were in

tended to be terminated at the appropriate time: when

the school system has achieved unitary status. Cf. Sivann,

402 U.S. at 28 (discussing the nature of the remedy to be

imposed in the “ interim period” until the effects of a dual

system are eliminated).

It is well established that “ an injunction often requires

continuing supervision by the issuing court,” System

Fed’n No. 91 v. Wright, 364 U.S. 642, 647 (1961), and

thus the issuing court may modify or dissolve an injunc

tive decree when “ it is no longer equitable that the judg

ment shall have prospective application.” Fed. B. Civ. P.

60(b) (5) ; see United Shoe Machinery Cory., 391 U.S. at

248; Wright, 364 U.S. at 646-48; United States v. Swift 6

6 See Pasadena City Bd. of Educ. v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424 (1976)

(district court exceeded authority by requiring- annual readjust

ment of attendance zones); cf. Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717

(1974) (district court exceeded its authority by ordering inter-

district remedy) ; Swann v. Charlotte-Mechlenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) (district court had remedial authority to decree

system of bus transportation and use mathematical ratios as starting

point).

14

& Co., 286 U.S. 106, 114 (1932) ; Pennsylvania v. Wheel

ing & Belmont Bridge Co., 59 U.S. (18 How.) 421 (1856).

“ ‘ [Sjound judicial discretion may call for the modifica

tion of the terms of an injunctive decree if the circum

stances, whether of law or fact, obtaining at the time of

its issuance have changed, or new ones have since

arisen.’ ” Pasadena City Bd. of Educ. v. Spangler, 427

U.S. 424, 437 (1976) (quoting System Fed’n No. 91 v.

Wright, 364 U.S. at 647). Because prospective injunc

tions are issued in a variety of differing contexts,7 the

determination whether an injunction should be modified or

dissolved “ must be based upon the specific facts and cir

cumstances” of the particular case. United Shoe Ma

chinery Corp., 391 U.S. at 249.

Most important, the determination whether to vacate or

modify a decree must be made in light of the substantive

law upon which the decree was based. A court’s authority

to enter an injunctive decree is necessarily derived from

the substantive law “which the decree is intended to

enforce.” System Fed’n No. 91 v. Wright, 364 U.S. at

651; see Ford Motor Co. v. EEOC, 458 U.S. 219, 241

(1982). In Wright, for example, the Court held that the

district court erred in refusing to modify a consent decree

under the Railway Labor Act in response to a change in

the underlying substantive law.8 When Congress had

7 See, e.g., United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp., 391

U.S. 244 (1968) (unlawful monopoly in shoe machinery market);

Chrysler Corp. v. United States, 316 U.S. 556 (1942) (unlawful

affiliation of automobile manufacturer and finance com pany); Fire

fighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts, 467 U.S. 561 (1984) (dis

crimination in city employment).

8 A consent decree, like a litigated decree, may be modified upon

the proper showing of changed circumstances. See System Fed’n

No. 91 V. Wright, 364 U.S. 642, 650-51 (1961). While the particular

substantive law may allow additional relief under a consent decree,

“ the court’s exercise of the power to modify the decree over the

objection of a party to the decree does implicate” the limits imposed

by the substantive law. Local No. 93, Int’l Ass’n of Firefighters V.

15

amended the Act to legalize one of the practices prohibited

by the decree, the Court made clear that the decree should

have been modified so that its terms would not “conflict

with statutory objectives.” Id.; see also Wheeling & Bel

mont Bridge Co., 59 U.S. (18 How.) at 429-32 (subse

quent congressional action legalizing bridge position re

quired modification of injunction to remove the bridge);

cf. Firefighters Local Union No. 1781 v. Stotts, 467 U.S.

561, 576 n.9 (1984) (modification of consent decree per

mitted only to extent it would be consistent with Title

V II). Only by referring to the substantive law that

formed the basis of the original decree may a court en

sure that its order remains consistent with its original

purpose. See United Shoe Machinery Cory., 391 U.S. at

251-252 (cases interpreting the Sherman Act define the

purposes of the antitrust injunction).

Because the underlying substantive law is an essential

check on a federal court’s power to issue and modify in

junctions, the heavy reliance of the court below on the

substantive standards for modification of antitrust de

crees was in error. The purposes of antitrust decrees are

to enjoin continuing and threatened violations by private

entities, to cure past violations and to deprive the defend

ants of any economic benefits from their past unlawful

acts. See United. States v. Crescent Amusement Co., 323

U.S. 173, 187-89 (1944) ; United, States v. Grinnell Cory.,

384 U.S. 563, 577-78 (1966). A prohibitory antitrust

decree such as that in Swift is particularly likely to be

impervious to modification because it is properly assumed

that the defendants will continue to act in their economic

self-interest and thus will not resist the temptation to

reap anti-competitive benefits, as long as market condi

tions permit such conduct. See United States v. Glaxo

City of Cleveland, 478 U.S. 501, 523 n.12 (1986) (original em

phasis) ; see also id. at 526-28 (consent decree must be consistent

with underlying substantive-law basis for decree).

16

Group, Ltd., 410 U.S. 52, 63 (1973); Crescent Amuse

ment Co., 323 U.S. at 190; see also United States V. Parke,

Davis & Co., 362 U.S. 29, 48 (1960) ; United States v.

United States Gypsum Co., 340 U.S. 76, 88-89 (1950).

Given the threat that, absent the injunction, the defendant

will resume the anti-competitive conduct, a scheme of

permanent mandatory relief is likely to be necessary to

achieve the purposes of the antitrust laws.

The standard for modifying the antitrust decree in

United States v. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106 (1932) —

which is the cornerstone of the decision below— incorpo

rates this concern for the ongoing threat of violation. In

Swift, the defendants sought a significant modification of

a 1920 consent decree which had imposed restraints on

the meat packers who had created “ an unlawful monopoly

of a large part of the food supply of the nation.” 286

U.S. at 111.9 In considering the requested modification,

the Court noted a distinction “ between restraints that

give protection to rights fully accrued upon facts so nearly

permanent as to be substantially impervious to change,

and those that involve the supervision of changing con

duct or conditions and are thus provisional and tentative.”

Id. at 114. The Swift injunction fell within the former

category because of the continuing threat of defendants’

monopolistic power that was “ one of the chief reasons”

for the original injunction. Id. at 115. The Court con

cluded that any changes in the meat market that may

have occurred were insignificant to affect “ the old-time

abuses in the sale of other foods,” and that the market

power wielded by the meat packers was a “ substantially

unchanged” fact. Id. at 117. Therefore, because the pur

9 Before the request for modification, two prior “vigorous as

sault [s ]” upon the decree were heard by this Court in Swift &

Co. v. United States, 276 U.S. 311 (1928) and United States v. Cali

fornia Coop. Canneries, 279 U.S. 553 (1929). Swift, 286 U.S. at 113.

The third suit attacking the decree was styled as a petition “ to

modify the consent decree and to adapt its restraints to the needs

o f a new day.” Id.

17

poses of the original decree had not been fully achieved

and the conduct which led to the decree was still threat

ened, the defendants had failed to demonstrate that the

decree should be modified. Id. at 116-120.10 11

Contrary to the opinion of the court of appeals in this

case (Dowell II, Pet. App. 12a (quoting Swift, 286 U.S.

at 119)), the burden of proof applied in Swift— the re

quirement to show unforeseen conditions giving rise to

grievous harm and the disappearance of the dangers ad

dressed by the decree— cannot be applied across the board

to all requests to modify or dissolve an injunctive decree.11

10 The Court made clear that the meat packers had sought to

modify the injunction while there was strong reason to believe

that the defendants would violate the antitrust laws if the restraints

were alleviated. See 286 U.S. at 117-119. Because defendants had

failed to make a showing that the threats of anticompetitive conduct

“ have become attenuated to a shadow” (id. at 119), the Court held

that “ [njothing less than a clear showing of grievous wrong evoked

by new and unforeseen conditions should lead us to change what

was decreed after years of litigation with the consent of all con

cerned.” Id. The decision makes clear that in order to achieve

the purposes of the antitrust laws, otherwise lawful business prac

tices may be enjoined as long as the defendants are in a position

to abuse their market power, absent the injunction. See id. at 116-

17. When this Court’s refusal to modify the antitrust decree in

Swift is therefore “ read in light of th[e] context” of the continuing

threat of unlawful restraints of trade that existed in that case

( United Shoe Machinery Corp., 391 U.S. at 248), it is clear that the

strict requirement of “ a clear showing of grievous wrong evoked by

new and unforeseen conditions” (Swift, 286 U.S. at 119), should

not apply to modification of injunctions governing education policy

— at least where the original violation has been cured.

11 The court of appeals incorrectly stated that Rule 60(b )(5 )

“ codifies” this statement in Swift. Dowell II, Pet. App. 13a. For

two reasons, it is clear that Rule 60 (b )(5 ) does not codify the

strict standard applied in Swift. First, Rule 60(b) simply codifies

the procedure for moving to modify an injunction; for example, it

“ does not assume to define substantive law as to the grounds for va

cating judgments, but merely prescribes the practice in proceedings

18

Instead of announcing an absolute standard for modify

ing all federal injunctions, Swift simply “ holds that [a

decree] may not be changed in the interests of the defend

ants if the purposes of the litigation as incorporated in

the decree (the elimination of monopoly and restrictive

practices) have not been fully achieved.” United Shoe

Machinery Corp., 391 U.S. at 248.12 * * * * *

Such a standard is particularly inappropriate in the

school desegregation context, where the purpose of the

injunction has been met and intentional (de jure) segre

gation and the effects of past intentional segregation have

been eliminated.18 See infra pages 24-28; Columbus Bd.

to obtain relief.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 60, Notes of Advisory Comm, on

1946 Amendment. Second, Rule 60(b) could not impose upon all

types of injunctions the rule applied to an antitrust decree, such as

in Swift, because such a rule would ignore the: substantive law

underlying the decree. See supra pages 13-17; cf. Stotts, 467

U.S. at 576 n.9 (disputed modification “cannot ibe resolved solely

by reference to the terms of the decree and notions o f equity” ).

12 According to the court of appeals, under the Swift standard a

school board must show that the changed conditions were unfore

seen and have created oppression. Dowell II, Pet. App. 12a. But the

nature of the school desegregation decree itself renders these prongs

an inappropriate basis for decision. First, changed conditions are

inherently foreseeable in every desegregation case because from, the

outset the decree envisions a day when it will end: each decree antici

pates that federal-court intervention will cease and local autonomy

will return when the vestiges of unlawful discrimination are elimi

nated root and branch. See Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S.

430 (1968). Second, oppression in its most basic sense occurs when

a federal court continues to control the day-to-day operation of

a public school system that has already achieved full unitary status.

18 Reliance upon the standard for modification or dissolution of

injunctive relief applied in antitrust cases against a private defen

dant is particularly inappropriate in a school desegregation case.

Even under the antitrust laws, a state actor, such as a school board,

has its conduct judged with regard to “principles of federalism and

state sovereignty.” Town of Hallie v. City of Eau Claire, 471 U.S.

34, 38 (1985). Thus, even if this were an antitrust case against a

19

of Educ. v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 458-59 (1979) ; Milliken

V. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267, 290 (1977); ( “Milliken II” ) ;

Spangler, 427 U.S. at 435; Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1,

Denver, Colo., 413 U.S. 189, 200-201 (1973) ; Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1, 31

(1971). That determination of whether a school system

has become unitary is extremely fact-specific and a matter

committed in large measure to the fact-finding of the dis

trict courts supervising the decree that are “ uniquely

situated . . . to appraise the societal forces at work in

the communities where they sit.” Penick, supra, 443

U.S. at 469-71 (Stewart, J,, concurring in Penick and

dissenting in Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S.

526 (1979) (“Dayton II” ) ) ; see also Broivn v. Board of

Educ., 347 U.S. 483, 495 (1954). But, at least, where

such a finding of unitariness has been entered (Dowell,

677 P. Supp. 1508, 1506 (W.D. Okla, 1987), Pet. App.

56), it is clearly impermissible to enjoin a school system

to continue operating under the same federal court injunc

tion that was entered in response to a finding of unlawful

de jure segregation, which, by definition, has been fully

remedied. See infra pages 25-27.

The purpose of the decree in Swift was to prohibit

threatened conduct.* 14 The purpose of all desegregation

decrees is to reach the point where they are no longer

needed— the elimination of the old dual system and its ef

fects “ root and branch.” Green v. County School Bd., 391

U.S. 430, 438 (1968). That point— unitary status— means

that the decrees have fully served their purpose. To con

public school system, it seems quite unlikely that the extreme stand

ards embodied in Swift would control. Accordingly, it makes no

sense to employ those requirements rigidly in such a completely

different legal setting.

14 There is no suggestion in the decisions of the court of appeals

and the district court that absent a federal injunctive restraint,

local authorities would return to a de jure segregated school system.

See Dowell, 677 F. Supp. 1503, 1515-16, 1519 (W.D. Okla. 1987)

(Pet. App. 24b-25b, 31b-33b); Dowell II, Pet. App. 41a.

20

tinue these decrees after this point in time is a groundless

incursion of federal power in local affairs.

II. THE DEMANDS OF THE EQUAL PROTECTION

CLAUSE PROVIDE THE PROPER RULE FOR DE

TERMINING WHETHER AN INJUNCTIVE DE

CREE AGAINST LOCAL SCHOOL AUTHORITIES

SHOULD BE CONTINUED.

The scope of a federal court’s equitable power does not

expand or change depending upon the stage in the life

of a case in which that power is exercised. Thus, the

determination whether an injunctive remedy should be

modified or vacated is bounded by the same substantive

law that defines the scope of the initial remedy: “ [a]s

with any equity case, the nature of the violation deter

mines the scope of the remedy.” Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1, 16 (1971).

Where the plaintiffs have established that state or local

authorities have violated the Fourteenth Amendment

through intentional discrimination on the basis of race, a

federal court’s “ equitable powers to remedy past wrongs

is broad, for breadth and flexibility are inherent in equi

table remedies,” id. at 15, but the court may exercise this

remedial power “ only on the basis of a constitutional vio

lation.” Id. at 16.15 Thus— regardless of the prior status

of the school district or the “ goals” of any existing order

— federal court “ decrees exceed appropriate limits if

they are aimed at eliminating a condition that does not

violate the Constitution or does not flow from such a

violation.” Milliken II, 433 U.S. at 282; see also Day-

ton Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406, 419-20

(1977) ( “Dayton I” ) ; Milliken I, 418 U.S. at 738; cf.

General Bldg. Contractors Ass’n, Inc. v. Pennsylvania,

458 U.S. 375, 399 (1982) (judicial remedial powers “ ex

tend no farther than required by the nature and the

extent of th[e] violation” ) ; Hills v. Gatreaux, 425 U.S.

15 See also Spangler, 427 U.S. at 443 (Marshall, J., dissenting)

(federal court has broad discretion to fashion remedial relief “until

such a unitary system is established” ) (quoting Swann, 402 U.S. at

31-32) (emphasis added).

21

284, 293-94 (1976); Rizzo v. Goode, 423 U.S. 362, 378

(1976).

In Milliken I, for example, this Court held that the

district court exceeded its remedial equitable powers by

ordering a desegregation remedy that extended beyond

the City of Detroit into the neighboring school districts.

This interdistrict remedy “was held to be an impermissi

ble remedy . . . because it contemplated a judicial decree

restructuring the operation of local governmental enti

ties that were not implicated in any constitutional viola

tion.” Hills v. Gatreaux, 425 U.S. at 296; Milliken I,

418 U.S. at 744-45; Swann, 402 U.S. at 16. Thus, at the

very least, it is well established that “ a federal court is

required to tailor ‘the scope of the remedy’ to fit ‘the

nature and extent of the constitutional violation.’ ”

Gatreaux, 425 U.S. at 293-94 (quoting Milliken I, 418

U.S. at 744). The decision below is contrary to this

fundamental axiom.

A. A Federal Court’s Equitable Discretion To Impose,

Modify Or Vacate An Injunction Structuring The

Operations Of Local School Districts Must Be In

formed By The Respect For Local Autonomy Em

bodied In Our Federalism.

The decision of the court of appeals is admittedly

aimed at maintaining racially balanced student popula

tions, even though the imbalance which exists if a race-

neutral neighborhood assignment method is instituted

cannot be traced to any unconstitutional conduct. The

court of appeals simply disagrees with the decision of

the local authorities who desire, for otherwise legitimate

reasons, to make the change. The racial balance that

the court of appeals has ordered maintained perpetually

is not necessary as “ an interim corrective measure”

(Swann, 402 U.S. at 27) ; rather, it simply reflects the

court’s preference for racially balanced schools. Yet, un

less used in a “ corrective” way, such a judgment invades

a province heretofore exclusively belonging to the states.

22

It is certainly arguable that Congress, exercising its

power to legislate under section 5 of the Fourteenth

Amendment (U.S. Const, amend. XIV, § 5), could make

this judgment over state objections, but Congress has al

ready spoken to the issue and agrees with the Oklahoma

City Board of Education.

The Congress declares it to be the policy of the

United States that-------. . . (2) the neighborhood is

the appropriate basis for determining public school

assignments.

20 U.S.C. § 1701(a) (2).

In both Milliken I and Gatreaux, this Court acknowl

edged concern that a federal court’s injunction restruc

turing local government operations in response to a

finding of a constitutional violation should be sensitive

to the constitutionally mandated federal-state relation

ship. See, e.g., Gatreaux, 425 U.S. at 294. Because a

federal court’s decision to enter or sustain a desegrega

tion order displaces the “ vital national tradition” of

“ local autonomy of school districts,” the exercise of these

powers is bounded by constitutional principles of fed

eralism. Dayton I, 433 U.S. at 410; Milliken I, 418

U.S. at 744-45; see also Spangler, 427 U.S. at 434-35;

Sivann, 402 U.S. at 15-16; cf. Firefighters Local Union

No. 1 7 8 v. Stotts, 467 U.S. 561, 576-77 n.9 (1984). The

court of appeals in this case, by importing standards for

modification of wholly private remedies, simply ignored

such considerations.

While this Court has never directly set forth the

framework for modifying injunctions issued to reform

state institutions, lower courts that must “grapple with

the flinty, intractable realities of day-to-day implemen

tation of th[e] constitutional commands” [Swann, 402

U.S. at 6), have long noted the need for flexibility in

modifying injunctions that structurally reform state

programs. In contrast, injunctions that allocate economic

rights among private parties (including, for example,

23

the antitrust injunction in Swift) do not implicate such

federalism concerns. Indeed, this Court recognized this

very distinction in United States v. Swift & Co., 286

U.S. at 114.16

A federal court in determining whether a decree

should be dissolved “ must be constantly mindful of the

‘special delicacy of the adjustment to be preserved be

tween federal equitable power and State administration

of its own law.’ ” Rizzo v. Goode, 423 U.S. 362, 378

(1976) (quoting Stefanelli v. Minard, 342 U.S.. 117, 120

(1951 )); see also Milliken II, 433 U.S. at 280-81. When

equity jurisdiction to fashion injunctive remedies is

vested in “ a system of federal courts representing the

Nation, subsisting side by side with 50 state judicial,

legislative, and executive branches, appropriate consider

ation must be given to principles of federalism in de

termining the availability and scope of equitable relief.”

Rizzo v. Goode, 423 U.S. at 379 (citing Doran v. Salem

Inn, Inc., 422 U.S. 922, 928 (1975) ) .17 Appropriate reeog-

16 The courts o f appeals also have noted this distinction in their

review of modification o f injunctions. See, e.g., Money Store, Inc.

V. Harriscorp Finance, Inc., 885 F.2d 369, 374-377 (7th Cir. 1989)

(Posner, J., concurring-); Kozlowski v. Coughlin, 871 F.2d 241, 247

(2d Cir. 1989); Twelve John Does v. District of Columbia, 861

F.2d 295, 298 (D.C. Cir. 1988); Badgley v. Scmtacroce, 853 F.2d

50, 52-53 (2d Cir. 1988) ; Plyler v. Evatt, 846 F.2d 208, 212 (4th

Cir.), cert, denied, 109 S.Ct. 241 (1988); Ruiz v. Lynaugh, 811

F.2d 856, 861 (5th Cir. 1987); Duran v. Elrod, 760 F.2d 756, 758

(7th Cir. 1985); Neivman v. Graddick, 740 F.2d 1513, 1520 (11th

Cir. 1984); Nelson v. Collins, 659 F.2d 420, 424 (4th Cir. 1981);

New York State Ass’n for Retarded Children, Inc. v. Carey, 706

F.2d 956, 967-71 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 464 U.S. 915 (1983); see

also Spangler V. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ., 611 F.2d 1239, 1245

n.5 (9th Cir. 1979) (Kennedy, Circuit Judge, concurring).

17 The Court recently reaffirmed that “ one of the most important

considerations governing the exercise of equitable power is proper

respect for the integrity and function of local government insti

tutions.” Missouri v. Jenkins, 58 U.S.L.W. 4480, 4484 (1990) ; see

also Spallone v. United States, 110 S.Ct. 625, 632 (1990) ( ‘“ [t]he

24

nition of such federalism concerns precludes considera

tion of requests to modify a desegregation decree under

a legal standard that presumes that the original injunc

tion will be permanent. See supra pages 16-20 and note

12.

B. A Federal Court’s Authority To Continue A School

Desegregation Decree Terminates When It Is Estab

lished That Intentional Segregation Has Ceased

And Current Conditions Are Not Attributable To

Prior Segregative Acts.

To justify the decree of injunctive relief, “ it must be

shown that racially discriminatory acts of the state or

local school districts . . . have been a substantial cause

of [the] segregation.” Miltiken I, 418 U.S. at 745 (em

phasis added); see also Spangler, 427 U.S. at 434 (plain

tiff must establish that “ school authorities have in some

manner caused unconstitutional segregation” ). Moreover,

when a violation of equal protection is alleged, a plaintiff

must establish that the state action which is being chal

lenged was adopted with a discriminatory purpose.

Keyes v. School Disk No. 1, Denver, Colo., 413 U.S. 189,

203 (1973); Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 239-41

(1976); Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Dev.

Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 264-66 (1977).

These principles are essentially embodied and applied

in Spangler. In Spangler, the Court reversed the refusal

of the district court to vacate a portion of an injunctive

decree after that decree had succeeded in remedying

completely the student assignment portion of the viola

tion previously found. Even though the Pasadena Unified

School District had not yet achieved complete unitary

federal courts in devising- a remedy must take into account the

interests of state and local authorities in managing their own

affairs, consistent with the Constitution’ ” ) (quoting Milliken II,

433 U.S. at 280-81).

25

status,18 19 the Court held that absent a finding that the

racial imbalance to which the decree was addressed

“ [w]as in any manner caused by segregative actions

chargeable to the defendants,” 427 U.S. at 435, there

could be no basis for “ judicially ordering assignment of

students on a racial basis.” Id. at 434; see also Swann,

402 U.S. at 28 ( “ [ajbsent a constitutional violation

there would be no basis for judicially ordering assign

ment of students on a racial basis” ) ,13

There is no principled way to reconcile the holding in

Spangler with the refusal of the court of appeals in this

case to vacate an injunction which requires assignment

of students on a racial basis in a school district which

the district court had found to have completed fully the

remedial process. Spangler stands squarely for the prop

osition that parts of a remedial decree in school desegrega

tion cases not aimed at remedying conditions causally

18 Spangler, 427 U.S. at 436. The Pasadena Unified School Dis

trict was not declared to have attained complete unitary status

until 1979. Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ., 611 F.2d 1239

(9th Cir. 1979).

19 In addition to the rule set forth in Swann and Spangler, this

Court’s standing doctrines provide a useful guide to the necessary

causal nexus between the constitutional violation and the scope of

a federal court’s equitable power. Both the standing inquiry and

the “ scope o f remedy” analysis Involve questions about causation

and its relationship to the question of a federal court’s power. See

Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737, 760 (1984) (whether a party is en

titled to injunctive relief is closely related to “ [c]ase-or-controversy

considerations” ). In order to invoke a federal court’s jurisdiction

to seek relief for an alleged injury, a plaintiff must demonstrate

(1) that the alleged injury “ fairly can be traced to the challenged

action” and (2) that the alleged injury is “ likely to be redressed”

by the requested relief. Simon v. Eastern Ky. Welfare Rights Org.,

426 U.S. 26, 38, 41 (1976). A similar inquiry should guide requests

for modification of injunctive relief; once the injunctive relief can

no longer be “ fairly traced” to an injury attributable to a consti

tutional violation, then the injunction should be lifted.

26

connected to unconstitutional conduct exceed the power

of federal courts and must be vacated. The decision be

low violates the holding in Spangler because it orders in

definite compliance with just such a decree.

In this case, the causal relationship between the school

authorities’ unconstitutional conduct and the segregative

effects were established in 1972. As the party moving for

modification, the school authorities have a “ burden . . .

to satisfy the court that their [current] racial composi

tion is not the result of present or past discriminatory

action on their part.” See Swann, 402 U.S. at 26; Keyes

v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, Colo., 413 U.S. at 211

n.17 (school authorities’ burden “ to show that current

segregation is in no way the result of these past segrega

tive actions” ). When this burden is met, however,

school authorities have no further “ duty” to remedy

a lack of racial balance due to demographic or other

factors and the injunction should be lifted. See Spangler,

427 U.S. at 436 (once the goal of the remedy is met,

federal court may not require annual adjustments “ to

ensure that the racial mix desired by the court was

maintained in perpetuity” ) ; Swann, 402 U.S. at 28

“ [albsent a constitutional violation there would be no

basis for judicially ordering assignment of students on

a racial basis” ). Applying this standard, the district

court found that the constitutional violation had been

cured over ten years ago and that the break in the causal

link between the violation and current conditions was

well established.

In light of such findings, the district court quite prop

erly held that further equitable relief could be imposed

only upon proof of a further constitutional violation. By

reversing that holding in favor of a more expansive view

of the Board’s “ duty,” the Tenth Circuit erroneously ex

panded the desegregation remedy beyond the scope of the

violation. As the Fifth Circuit correctly noted in United

States v. Overton,

27

continuing limits imposed as a remedy after the

wrong is righted effectively changes the constitu

tional measure of the wrong itself; it transposes the

dictates of the remedy for the dictates of the Con

stitution and, of course, they are not interchange

able.

834 F.2d 1171, 1176 (5th Cir. 1987).20 In ordering the

school board to remedy the lack of racial balance caused

by demographic changes, the Tenth Circuit has done ex

actly what the Fifth Circuit warned against: it has sub

stituted racial balance rather than the “undoing” of un

lawful segregation as the baseline of the remedial order.21

In sum, the fundamental error of the court of appeals

in this case— and of the Eleventh Circuit in Freeman V.

Pitts— was to measure current conditions in the schools

against a standard or “goal” that was not closely tied

to the scope of the substantive violation, as defined by the

Constitution. The court of appeals’ rejection of any re

quirement of a causal link between the condition being

remedied and a violation of the Constitution (as was

advocated by the United States, see Dowell / , 795 F.2d

2° xhe Fifth Circuit stated that the desire to press for remedies

beyond the segregation caused by the constitutional violation “ rests

upon a fear that the Fourteenth Amendment, proscribing as it does

only purposeful discrimination, inadequately protects desegrega

tion gains . . . .” Overton, 834 F.2d at 1176.

21 Despite the understandable desire o f the court below to “ pro

tect” the goal of a racially balanced student body,

accommodation of federal superintendence and federalism will

not tolerate the idea that although the wrong is righted, the

magnitude o f the past wrong nonetheless justifies perpetuation

of a federal order limiting the ambit of a school district’s self-

governance.

Overton, 834 F.2d at 1177. The standard adopted by the court

below simply fails to recognize that “ [i]t is state government that

[the court was] asked to enjoin” and that, “ having righted the

wrong, the limits [the court should] impose on the state can be

drawn no more tightly than the limits of the Constitution.” Id,

28

at 1520) opens the door to virtually limitless remedial

litigation in which local governments will be ordered to

undertake extraordinary remedies in pursuit of a “ per

fect” racially-balanced school system— a “ solution that

may be unattainable in the context of the demographic,

geographic, and sociological complexities of modern

urban communities.” Estes v. Metropolitan Branches of

the Dallas NAACP, 444 U.S. 437, 448 (1980) (Powell,

J., dissenting). Because such a result is contrary to the

requirements of the Constitution and contrary to funda

mental equitable principles, the decision below must be

reversed.

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the court of appeals should be re

versed.

Respectfully submitted,

Gary M. Sam s

Charles L. Weatherly

J. Stanley Hawkins

Weekes & Candler

One Decatur Town Center

Suite 300

Decatur, Georgia 30031

(404) 378-4300

Rex E. Lee *

Carter G. Phillips

Mark D. Hopson

Nancy A. Temple

Sidley & Austin

1722 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 429-4000

Counsel for DeKalb County Board of Education,

As Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioner

June 1,1990 * Counsel of Record