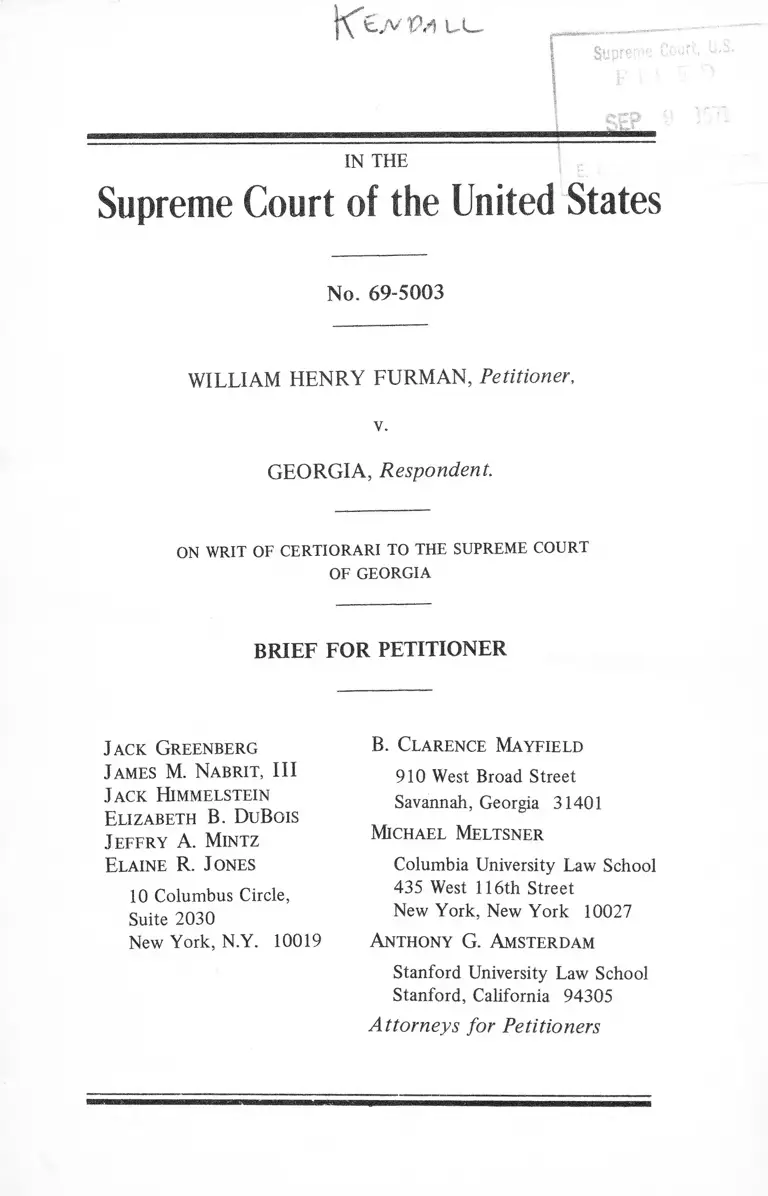

Furman v. Georgia Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

September 9, 1971

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Furman v. Georgia Brief for Petitioner, 1971. 85eaff90-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3e26fec7-22b8-4c4a-a1de-9ce20c4a7182/furman-v-georgia-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed March 09, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 69-5003

WILLIAM HENRY FURMAN, Petitioner,

v.

GEORGIA, Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

J ack G r e e n b e r g

J ames M. N a b r it , III

J ack H im m elstein

E liza b eth B. Du Bois

J e f f r y A. M in tz

E la in e R. J ones

10 Columbus Circle,

Suite 2030

New York, N.Y. 10019

B. C la r en c e Ma y f ie l d

910 West Broad Street

Savannah, Georgia 31401

Mic h a e l Me l t sn e r

Columbia University Law School

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

An t h o n y G. Am sterd a m

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

Attorneys for Petitioners

INDEX

Page

OPINION BELOW ................................................................. .. 1

JURISDICTION................................... 1

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS

INVOLVED................................................................................ 2

QUESTION PRESENTED....................................................... 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE....................................................... 2

HOW THE CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTION WAS

PRESENTED AND DECIDED BELOW ................................. 10

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.................................................. 11

ARGUMENT:

I. The Death Penalty for Murder Violates Contempo

rary Standards of Decency in Punishment.................... 11

II. Petitioner’s Sentence of Death Imposed Without

Adequate Inquiry Concerning His Manifestly Im

paired Mental Condition Violates the Eighth

Amendment .................................................................... 12

CONCLUSION................................................................................ 20

APPENDIX A: STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED------ la

APPENDIX B: PSYCHIATRIC REPORTS................................. lb

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Caritativo v. California, 357 U.S. 549 (1958) ............................ 19

Crampton v. Ohio, reported sub nom. McGautha v. Califor-

Nia, 402 U.S. 183 (1971).................................................. 18

Ex parte Medley, 134 U.S. 160 (1890)........................................ 16

Musselwhite v. State, 215 Miss. 363, 60 So.2d 807 (1952) . . . 15

Nobles v. Georgia, 168 U.S. 398 (1 8 9 7 )...................................... 19

Pate v. Robinson, 383 U.S. 375 (1966) ...................................... 18

Phyle v. Duffy, 334 U.S. 431 (1 9 4 8 )...........................................

(i)

(ii)

Rogers v. State, 128 Ga. 67, 57 S.E. 227 (1 9 0 7 )....................... 16

Solesbee v. Balkcom, 339 U.S. 9 (1950 ).............................. 13, 14, 18

Summerour v. Fortson, 174 Ga. 862, 164 S.E. 809 (1932) . . . 16

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) ............................ 3

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions:

Eighth Amendment, U.S. Constitution ........................................ 2, 10,

11, 12, 18, 19,20

Fourteenth Amendment, U.S. Constitution............................2, 10, 18

28 U.S.C. § 1257(3)....................................................... ................ 1

Ga. Code Ann. § 26-1001 ............................................................. 2, 6

Ga. Code Ann. § 26-1002 ...................................................... 2, 6

Ga. Code Ann. i 26-1005 ............................................................. 2,7

Ga. Code Ann. § 26-1009 .............................................................. 2 ,8

Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2512 ................................................. 2, 7

Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2602 .............................................................. 2,18

Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2604 .............................................................. 2,18

Other Authorities:

4 BLACKSTONE, COMMENTARIES (1803) ............................ 13, 14

Bluestone & McGahee, Reaction to Extreme Stress:

Impending Death by Execution, 119 AM. J.

PSYCHIATRY 393 (1 9 6 2 )....................................................... 17

Brief for Petitioner, Aliens v. California, O.T. 1971, No.

68-5027...................................................................................11, 12, 17

Camus, Reflections on the Guillotine, in CAMUS,

RESISTANCE, REBELLION AND DEATH (1961) ........... 16

CHITTY, CRIMINAL LAW (Earle ed. 1 8 19 ).............................. 13

COKE, THIRD INSTITUTE (1644) ................................... .. 13, 14

Zifferstein, Crime and Punishment, 1 THE CENTER

MAGAZINE (No. 2) 84 (Center for the Study of

Democratic Institutions 1968) ............................................... I7

DUFFY & HIRSHBERG, 88 MEN AND 2 WOMEN (1962) . . . I7

DUFFY & JENNINGS, THE SAN QUENTIN

STORY (1950 ).......................................... 17

Ehrenzweig, A Psychoanalysis o f the Insanity Plea-Clue to

the Problem o f Criminal Responsibility and Insanity in

the Death Cell, 1 CRIM. L. BULL. (No. 9 3 (1965)

[cited as Ehrenzweig] ..........................................................14, 17, 19

ESHELMAN, DEATH ROW CHAPLAIN (1962) ....................... 17

Feltham, The Common Law and the Execution o f Insane

Criminals, 4 MELBOURNE L. REV. 434 (1 9 6 4 ) .................. 19-20

Gottlieb, Capital Punishment, 15 CRIME & DELINQUENCY

1 (1969) ................................................................................... 17

1 HALE, PLEAS OF THE CROWN (1678 )................................. 13

1 HAWKINS, PLEAS OF THE CROWN (1716) ....................... 13

Hawles, Remarks on the Trial of Mr. Charles Bateman, 11

Howell State Trials 474 (1 8 1 6 )..........................................13, 14, 15

Hazard & Louisell, Death, the State, and the Insane:

Stay o f Execution, 9 U.C.L.A. L. REV. 381 (1962)

[cited as Death, the State, and the Insane] ............................ 15, 19

LA WES, LIFE AND DEATH IN SING SING (1928) ............... 16, 17

LA WES, TWENTY THOUSAND YEARS IN SING SING

(1932)........................................................................... .............. 17

ROYAL COMMISSION ON CAPITAL PUNISHMENT,

MINUTES OF EVIDENCE (1949) [cited as ROYAL

COMMISSION M INUTES]..........................................................13, 14

ROYAL COMMISSION ON CAPITAL PUNISHMENT 1949-

1953, REPORT (H.M.S.O. 1953)[Cmd. 8932] [cited as

ROYAL COMMISSION] .....................................................13, 14, 19

WEIHOFEN, MENTAL DISORDER AS A CRIMINAL

DEFENSE (1954) 14, 19

WEIHOFEN, THE URGE TO PUNISH (1956)............................ 14

West, Medicine and Capital Punishment, in Hearings Before

the Subcommittee on Criminal Laws and Procedures o f

the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 90th Cong., 2d

Sess., on S. 1760, To Abolish the Death Penalty (March

20-21 and July 2, 1968) (G.P.O. 1970) 16

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 69-5003

WILLIAM HENRY FURMAN, Petitioner,

v.

GEORGIA, Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

OPINION BELOW

The syllabus opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia

affirming petitioner’s conviction of murder and sentence of

death by electrocution is reported at 225 Ga. 253, 167 S.E.

2d 628, and appears in the Appendix [hereafter cited as

A.____] at A. 66-68.

JURISDICTION

The jurisdiction of this Court rests upon 28 U.S.C.

§ 1257(3), the petitioner having asserted below and assert

ing here a deprivation of rights secured by the Constitution

of the United States.

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia was

entered on April 24, 1969. (A. 68.) A petition for certio

rari was filed on July 23, 1969, and was granted (limited

to one question) on June 28, 1971 (A. 69).

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case involves the Eighth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States, which provides:

“Excessive bail shall not be required, nor exces

sive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punish

ments inflicted.”

It involves the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

It further involves Ga. Code Ann. §§ 26-1001, 26-1002,

26-1005, 26-1009, 27-2512, 27-2602, 27-2604 which are

set forth in Appendix A to this brief [hereafter cited as

App. A, pp.____], at App A, pp. la - 4a, infra.

QUESTION PRESENTED

Does the imposition and carrying out of the death pen

alty in this case constitute cruel and unusual punishment

in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Petitioner William Henry Furman was convicted of mur

der and sentenced to die following a one-day jury trial in

the Superior Court of Chatham County, Georgia, on Sep

tember 20, 1968. (A. 10-65.) The trial was very brief.

Jury selection began at about 10:00 a.m.;1 the taking of

'One venireman was excused for cause over petitioner’s objec

tion (A. 13-14 [Tr. 6-9]) because of his opposition to the death pen

alty. He was asked if he would refuse to impose capital punishment

3

evidence and the court’s charge to the jury were concluded

by approximately 3:30 p.m. (A. 64 [Tr. 119]); the jury

retired at 3:35 p.m. (ibid.) and returned its death verdict

at 5:10 p.m. (ibid.).

The murdered man was William Joseph Micke, Jr. His

widow testified at the trial that Mr. Micke was twenty-nine

years old, and lived with her and five children—ranging in

age from one to fifteen—in a house in the City of Savannah.

(A. 17-18 [Tr. 12-13.]) Mr. Micke was employed by the

Coast Guard; and on August 11, 1967, he began work at a

second job, at the Tiffany Lounge, to supplement his in

come. (A. 18 [Tr. 13].) He returned home from that job

at about midnight; then he and his wife retired for the

night. (Ibid.)

Between 2:00 and 2:30 a.m., Mr. and Mrs. Micke heard

noise coming from the dining room or kitchen area of the

house. They thought that it was their eleven year-old son

sleepwalking, and Mr. Micke went to investigate. Mrs. Micke

heard him call the boy, heard his footsteps quicken, then

heard “a real loud sound and he screamed.” (A. 19 [Tr.

15]; see A. 17-19 [Tr. 13-15].) She ran and locked her

self with her children in her daughters’ bedroom, where they

all began to shout for the neighbors. The neighbors came

in a few minutes, and Mrs. Micke immediately phoned the

police who arrived shortly thereafter. (A. 19-20, 21-22

[Tr. 15-16, 19-20].) From her testimony and that of an

investigating officer, the jury could find that Mr. Micke’s

assailant had entered the rear porch of the house through

in a case regardless of the evidence, and said, “I believe I would” (A.

13 [Tr. 5]); when asked whether his opposition to the death penalty

would affect his decision as to a defendant’s guilt, he said “I think

it would” (Ibid.). Veniremen were not excused for cause who,

although opposed to capital punishment, said that they could impose

it in some circumstances, and that their attitudes toward capital

punishment would not prevent them from making an impartial deter

mination of the defendant’s guilt. (A. 12, 14-15 [Tr. 4, 7-9].) The

Georgia Supreme Court held that this form of death qualification was

proper under Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968). (A. 66.)

4

a screen door (which might or might not have been locked),

had moved a washing machine away from the porch wall

outside the kitchen window, and had reached through the

kitchen window to unlatch the kitchen door from the in

side. (A. 19-21, 25 [Tr. 16-19, 24].)

The investigating officer, responding to a call at the

Mi eke house at about 2:30 a.m., found Mr. Micke lying

dead on the kitchen floor. (A. 24-26 [Tr. 23-26].) The

cause of death was later determined to be a single pistol

wound which entered Mr. Micke’s upper chest near the mid-

line and passed through the lung causing severe hemorrhag

ing. (A. 32 [Tr. 35-36].) The bullet which produced this

wound had been fired through the kitchen door from the

outside while the door was closed. (A. 27, 29-30 [Tr. 28,

31-32].) Only one bullet hole was found in the door (A.

55 [Tr. 92-93]), which was constructed of solid plywood

with no window (A. 20, 22, 29 [Tr. 17, 20-21, 31 ]). The

prosecution adduced no evidence that more than this one

shot was fired at the Micke house that night.2

Petitioner Furman was identified as Mr. Micke’s killer

because his fingerprints, taken following his arrest, matched

several latent prints that were lifted from the surface of the

washing machine on the Mickes’ rear porch. (A. 33-34, 35-

36 [Tr. 40-43, 50-55].) Petitioner was also seen and ap

prehended leaving the area with the murder weapon shortly

after the killing, under the following circumstances.

One of the officers who had been called to the Micke

house went thence to a street bordering a wooded area

south of the house. He saw a man emerge from the woods,

walking from the north. The man saw the officer and

began to run. The officer called several other officers who

2When petitioner was arrested in possession of the murder gun

shortly thereafter (see text, infra), the gun contained three live bul

lets and three expended shells. (A. 42 [Tr. 65].) However, there is

no evidence that more than one of these shells was fired at the Micke

house. (A. 55 [Tr. 92].)

5

took up pursuit. Two followed foot-tracks left by the flee

ing man in the rain. These led to the nearby house of Mr.

James Furman, petitioner’s uncle. (A. 38-39 [Tr. 59-61].)

The officers followed the tracks around the house to an

area which gave entrance to the space under the house.

They shined their flashlights in, saw petitioner under the

house, and called him out. (A. 39-40 [Tr. 61-62].) Peti

tioner “reached as if he was reaching for his back pocket

and [one officer] . . . pulled [his] . . . pistol and . . .

pointed it at him and . . . told him to come out and don’t

make any move.” [A. 40 [Tr. 62].) The officers then

pulled petitioner out from under the house, searched him,

and found a .22 caliber pistol in “his right front pocket.”

(A. 42 [Tr. 64]; see also A. 40 [Tr. 63].) This pistol was

later identified ballistically as the one which fired the bul

let that killed Mr. Micke. (A. 42, 43, 49-50 [Tr. 65, 67-

68, 80-81].)

Petitioner was the only eyewitness to the circumstances

of Mr. Micke’s killing. Two versions of those circumstances

were put before the jury at the trial. A detective who ques

tioned petitioner after his arrest testified that petitioner

said:

“that he was in the kitchen; the man came in the

kitchen, saw him in there and attempted to grab

him as he went out the door; said the man hit the

door-instead of catching him, he hit the door, the

door slammed between them, he turned around and

fired one shot and ran.” (A. 47 [Tr. 77]; see also

A. 44-45; 49 [Tr. 71-73, 79].)

In his unsworn statement at trial,3 petitioner denied mak

ing this declaration (A. 54-55 [Tr. 91-92]); he said:

“I admit going to these folks’ home and they did

caught me in there and I was coming back out,

3Under Georgia practice following Ferguson v. Georgia, 365 U.S.

570 (1961), a criminal defendant may elect to testify under oath,

questioned by his attorney and cross examined by the prosecutor, or

to make an unsworn statement without questioning or cross exami

nation. Petitioner “elected” the latter course. See note 8 infra.

6

backing up and there was a wire down there on the

floor. I was coming out backwards and fell back

and 1 didn’t intend to kill nobody. 1 didn’t know

they was behind the door. The gun went off and

I didn’t know nothing about no murder until they

arrested me, and when the gun went off I was down

on the floor and I got up and ran. That’s all to it.”

(A. 54-55 [Tr. 91].)

It is impossible to know, of course, which of those ver

sions of the facts—if either—the trial jury believed. But, as

the case comes to this Court, it must be taken to be one

in which the Georgia courts have permitted the imposition

of a death sentence for an unintended killing, committed

by the accidental discharge of a pistol during petitioner’s

flight from an abortive burglary attempt. This is so for sev

eral reasons.

First, Georgia law allows the imposition of the death sen

tence upon such a basis. Like the common law, but unlike

the statutory law of most American jurisdictions today,

Georgia does not divide murder into degrees. It maintains

two crimes of homicide: murder and manslaughter. Ga.

Code Ann., § 26-1001, App. A, p. la infra. The hallmark

of murder is, as at common law, “malice aforethought,” see

Ga. Code Ann., § 26-1002, App. A, p. la infra; but a pro

viso to Ga. Code Ann., § 26-1009 creates a form of con

structive malice, or of “felony-murder,” by providing that

even unintended killings are murder if they “happen in the

commission of an unlawful act which, in its consequences,

naturally tends to destroy the life of a human being, or is

committed in the prosecution of . . . a crime punishable by

death or confinement in the penitentiary.” App. A, p. 2a

infra. The punishment for murder by any person seventeen

years of age or older is death by electrocution, except that

(1) the jury may make a binding recommendation, in its

sole discretion, that the punishment shall instead be life

imprisonment; and (2) if the conviction is based solely on

circumstantial testimony, the presiding judge is also given

discretion to impose a sentence of life imprisonment not

7

withstanding the jury’s death verdict. Ga. Code Ann. §§ 26-

1005, 27-2512, App. A, pp. la-3a infra.

Second, the jury charge in this case permitted a murder

conviction, and thereby a death sentence, if petitioner’s

killing of Mr. Micke was found to be either (a) actuated by

“express malice” (i.e., an intentional killing) (A. 61-62 [Tr.

114-115]), or (b) the product of “implied malice,” defined

to include “the killing of a human being by the intentional

use of a weapon that as used is likely to kill and a killing

without justification, mitigation or excuse” (A. 62 [Tr. ■

115 ]), or (c) “an involuntary killing . . . in the commission of

an unlawful act which in its consequences naturally tends to

destroy the life of a human being or . . . in the prosecution

of a crime punishable by . . . confinement in the peniten

tiary” (A. 62-63 [Tr. 115-116])—here, the crime of bur

glary (A. 62-63 [Tr. 116-117)]. The jury was specifically

instructed:

“If you believe beyond a reasonable doubt that

the defendant broke and entered the dwelling of the

deceased with intent to commit a felony or a lar

ceny and that after so breaking and entering with

such intent, the defendant killed the deceased in the

manner set forth in the indictment, and if you find

that such killing was the natural, reasonable and

probable consequence of such breaking and enter

ing then, I instruct you that under such circum

stances, you would be authorized to convict the

defendant ol murder and this you would be author

ized to do whether the defendant intended to kill

the deceased or not.” (A. 63 [Tr. 117].)4 5 4

4Petitioner challenged this instruction as erroneous in paragraph

7 of his Amended Motion for New Trial (R. 34, 42-43), which was

overruled (R. 46). [Here and hereafter, references in the form R.__

designate pages of the Clerk’s Record in the Superior Court of Chat

ham County, which is contained in the original record filed in this

Court.] The same claim was incorporated by reference in paragraph

7, p. 2, of his Enumeration of Errors filed March 28, 1969, in the

8

Third, the Georgia Supreme Court rejected petitioner’s

claim of insufficiency of the evidence upon the express

ground that even an involuntary killing in the course of a

burglary was murder, and in express reliance upon petitio

ner’s trial statement:

“The admission in open court by the accused in

his unsworn statement that during the period in

which he was involved in the commission of a crim

inal act at the home of the deceased, he accidentally

tripped over a wire in leaving the premises causing

the gun to go off, together with other facts and cir

cumstances surrounding the death of the deceased

by violent means, was sufficient to support the ver

dict of guilty of murder. . . (A. 67-68.)

The jury which sentenced petitioner to die knew nothing

about him other than the events of one half-hour of his life

on the morning of August 12, 1967-as just recited-and

the fact that he was black.* 6 However, additional facts ap

Georgia Supreme Court. [This document is contained in, but is not

paginated as a part of, the original record in this Court.]

sThe court further charged the jury that, if it convicted the peti

tioner of murder, it might sentence him to death by electrocution or

to life imprisonment without giving “any reason for its action in fix

ing the punishment at life or death.” “The punishment is an alter

native punishment and may be one or the other as the jury sees fit.”

(A. 64 [Tr. 118].)

6The cursory nature of the trial which determined that petitioner

would die resulted from his indigency. Because petitioner was a pau

per, the court appointed counsel to represent him. Under Georgia

practice, appointed counsel was compensated $150 for defending a

capital murder case. See the affidavit of B. Clarence Mayfield, Esq.,

dated May 5, 1969, filed in the Georgia Supreme Court and included

in the original record in this Court. Counsel sought by written pre

trial motions: (1) funds for a defense investigator, (2) “reasonable

compensation [for counsel] to enable them [sic: him] to devote the

necessary time to prepare a case of this kind,” and (3) relief from

the requirement that counsel “advance the expenses in the prepara

tion of a trial in the lower court without knowing whether or not

such expenses will be reimbursed to him.” (Motions, paragraphs 2,

3, 4, R. 12-13.) Each of these requests was denied. (Order, R. 15.)

9

pear in the record which this Court may properly consider

as bearing on the question whether the State of Georgia will

be carrying out a cruel and unusual punishment if it elec

trocutes William Henry Furman. Those facts indicate, in

summary, that Petitioner Furman is both mentally deficient

and mentally ill.

On October 24, 1967—ten weeks after Mr. Micke’s killing

and almost a year prior to petitioner’s trial—the trial court

ordered petitioner committed to the Georgia Central State

Hospital at Milledgeville for a psychiatric examination upon

his special plea of insanity. (A. 8.) On February 28, 1968,

the Superintendent of the Hospital reported by letter to the

court that a unanimous staff diagnostic conference on the

same date had concluded “that this patient should retain

his present diagnosis of Mental Deficiency, Mild to Mode

rate, with Psychotic Episodes associated with Convulsive

Disorder.” The physicians agreed that “at present the

patient is not psychotic, but he is not capable of cooperat

ing with his counsel in the preparation of his defense;” and

the staff believed “that he is in need of further psychiatric

hospitalization and treatment.” (App. B, p. 2b infra.)1

By a subsequent letter of April 15, 1968, the Superintend

ent reported the same staff diagnosis of “Mental Deficiency,

Mild to Moderate, with Psychotic Episodes associated with

Convulsive Disorder,” but concluded that petitioner should

now be returned to court for trial because “he is not psy

chotic at present, knows right from wrong and is able to

cooperate with his counsel in preparing his defense.” (Id.,

at 3b-4b.) At the time of trial, petitioner was twenty-six

7The reference is to Appendix B to this brief. That Appendix

sets forth the texts of the two letters described in this paragraph, and

explains why they may properly be considered by this Court although

they were not before the Georgia Supreme Court.

10

years old,8 had gotten to the sixth grade in school,9 and

was visibly confused by aspects of the proceedings against

him.10

HOW THE CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTION

WAS PRESENTED AND DECIDED BELOW

Paragraph 3 of petitioner’s Amended Motion for New

Trial, filed by leave of court, contended that the death sen

tence which had been imposed upon him was a cruel and

unusual punishment forbidden by the Eighth and Four

teenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United

States. (R. 34, 38-39.) The motion was overruled. (R. 46.)

Paragraph 4 of petitioner’s Enumeration of Errors in the

Petitioner recited his age in Iris unsworn statement to the jury.

(A. 54 [Tr. 91].)

9Petitioner’s level of schooling was elicited from him, out of the

presence of the jury, while he was being questioned by his counsel

and the court in order to determine whether he wished to take the

stand. (A. 53 [Tr. 89].)

10At the conclusion of the prosecution’s case, the jury was ex

cused, and petitioner’s court-appointed counsel asked leave of the

court to put the defendant on the stand “to ascertain from him

whether or not, for the record, he wishes to make a sworn or unsworn

statement or no statement at all.” (A. 50 [Tr. 84]). See note 3

supra. In yes-and-no responses to counsel’s questioning, petitioner

stated that counsel had previously talked with him and advised him

concerning his making a statement to the jury; and petitioner said

and repeated that he did not want to make such a statement. (A.

51-52 [Tr. 85-86.]) The court and counsel then advised petitioner

again concerning his rights to make a sworn or unsworn statement

or no statement; petitioner was asked if he understood “what we are

trying to ask you” ; and he replied: “Some of it I don’t.” (A. 52-53

[Tr. 86-89].) He then answered “yes” to the court’s question

whether he wanted to tell the jury anything, and repeated this “yes.”

(A. 53 [Tr. 89].) Without further inquiry regarding the reasons for,

or advisedness of, petitioner’s unexplained change of mind, counsel

and the court treated this response as an election to make an un

sworn statement; the jury was recalled; and petitioner took the

stand. (A. 54 [Tr. 90].)

Georgia Supreme Court made the same contention.11 The

Georgia Supreme Court rejected it upon the merits. (A. 67.)

! I

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. Petitioner’s sentence of death is a rare, random and

arbitrary infliction, prohibited by the Eighth Amendment

principles briefed in Aikens v. California.

II. The Eighth Amendment forbids affirmance of a death

sentence upon this record, which casts doubt upon petitio

ner’s mental soundness. To relegate petitioner to the tor

ments and vicissitudes of a death sentence without appro

priate inquiry into his mental condition is to subject him

to cruel and unusual punishment.

I.

THE DEATH PENALTY FOR MURDER VIOLATES

CONTEMPORARY STANDARDS OF

DECENCY IN PUNISHMENT

The Brief for Petitioner in A ik en s v. California 12 fully

develops the reasons why we believe that the death penalty

is a cruel and unusual punishment for the crime of murder,

as that penalty is administered in the United States today.

At the heart of the argument is the principle that the

Eighth Amendment condemns a penalty which is so oppres

sive that it can command public acceptance only by spora

dic, exceedingly rare and arbitrary imposition.

Petitioner’s case epitomizes that characteristic of the

penalty of death for murder. His was a grave offense, but

one noways distinguishable from thousands of others for

n P. 1 of the Enumeration of Errors, filed March 28, 1969. [This

document is contained in, but is not paginated as a part of, the origi

nal record filed in this Court.]

n 0.T. 1971, No. 68-5027.

12

which the death penalty is not inflicted. Following a brief

trial which told the jury nothing more than that petitioner

had killed Mr. Micke by a single handgun shot through a

closed door during an armed burglary attempt upon a dwell

ing—and which permitted his conviction whether or not the

fatal shot was intentionally fired—he was condemned to die.

The jury knew nothing else about the man they sentenced,

except his age and race.

It is inconceivable to imagine contemporary acceptance

of the general application of the death penalty upon such

a basis. Only wholly random and arbitrary selection of a

few, rare murder convicts makes capital punishment for

murder tolerable to our society. For the reasons stated in

the Aikens brief, it is not tolerable to the Eighth Amend

ment.

II.

PETITIONER’S SENTENCE OF DEATH IMPOSED WITHOUT

ADEQUATE INQUIRY CONCERNING HIS MANIFESTLY IM

PAIRED MENTAL CONDITION VIOLATES THE EIGHTH

AMENDMENT

But there is an additional reason why the sentence of

death imposed on this petitioner cannot constitutionally

stand. The record in this case bears plain indications that

petitioner is mentally ill. The imposition of a death sen

tence upon him without adequate inquiry concerning either

his competency to be executed or his capability to with

stand the stress of such a sentence violates the Eighth

Amendment.

(1) This Court need not look to evolving standards of

decency for evidence that the execution of a mentally dis

ordered person offends the most basic human precepts

embodied in our legal history. Coke in 1644 wrote that in

earlier years it had been provided that:

“. . . if a man attainted of treason become mad,

that notwithstanding he should be executed which

13

cruell and inhuman law lived not long, but was re

pealed, for in that point also it was against the com

mon law, because by intendment of law the execu

tion of the offender is for example, ut poena ad

paucos, metus ad omnes perveniat, as before is said:

but so it is not when a mad man is executed, but

should be a miserable spectacle, both against law

and of extreme inhumanity and cruelty, and can be

no example to others.” (COKE, THIRD INSTI

TUTE (1644), 6.)13

The British Royal Commission on Capital Punishment

concluded that:

“It has for centuries been a principle of the com

mon law that no person who is insane should be

executed . . . (ROYAL COMMISSION ON CAP

ITAL PUNISHMENT 1949-1953, REPORT (H.M.S.O.

1953) [Cmd. 8932] [hereafter cited as ROYAL

COMMISSION], 13.14 * * * *

The Commission found that “the Home Secretary is under

a statutory obligation to order a special medical inquiry if

there is reason to believe that a prisoner under sentence of

death is insane, and similar inquiries are often held where

a lesser degree of abnormality is suspected.” ROYAL COM-

13See also, 1 HAWKINS, PLEAS OF THE CROWN (1716), 2; 4

BLACKSTONE, COMMENTARIES (1803), 24; Hawles, Remarks

on the Trial of Mr. Charles Bateman, 11 Howell State Trials 474, 476

(1816); CHITTY, CRIMINAL LAW (Earle Ed. 1819), 525; 1 HALE,

PLEAS OF THE CROWN (1678), 35, 370; and the authorities cited

in the dissenting opinion of Mr. Justice Frankfurter in Solesbee v.

Balkcom, 339 U.S. 9, 16-20, (1950).

14See also ROYAL COMMISSION 123; Testimony of Sir John

Anderson, ROYAL COMMISSION ON CAPITAL PUNISHMENT,

MINUTES OF EVIDENCE (1949) [hereafter cited as ROYAL COM

MISSION MINUTES], 363:

“As was stated in the House of Commons in the case of

Ronald True, ‘the principle that an insane man should not

go to execution has been enshrined in the Common Law

since the days of Coke and Hale.’ ”

See also, e.g., id. at 3, 40, 128.

14

MISSION 13. In the event the doctors who examined the

condemned man found him insane, the Home Secretary was

required to respite the sentence.

“ [I]t is not only right and proper that the Home

Secretary should respite the sentence of death and

direct the prisoner’s removal to Broadmoor or to a

mental hospital, but it is his imperative duty to do

so, both under the statute and because it is contrary

to the common law to execute an insane criminal.”

(ROYAL COMMISSION 127.)15

The reasons advanced for this traditional prohibition have

been varied. They include the notions that an insane per

son can not bring evidence on his own behalf to defeat the

sentence,16 that the execution of an insane person cannot

reasonably be thought to deter others,17 that an insane per

son is not mentally fit to make peace with his maker,18 that

he has already been punished sufficiently by God or by the

" fk devil,19 * and that the execution of an insane person would

------------

k * * 15See also ROYAL COMMISSION MINUTES 3, 47, 372, 380.

C%C-*1' |_ ^ For general discussion of the British procedure, see ROYAL COM-

MISSION 2, 124-130; ROYAL COMMISSION MINUTES 2, 40, 246,

f jV 256, 352, 522; WEIHOFEN, THE URGE TO PUNISH (1956), 52-53.

V See also WEIHOFEN, THE URGE TO PUNISH (1956), 52-53. See

«|Vt, . “\also WEIHOFEN, MENTAL DISORDER AS A CRIMINAL DEFENSE

\ A ^ / ( i 9 5 4 ), 463-470; Solesbee v. Balkcom, 339 U.S. 9, 26-32 (1950) (dis

senting opinion of Mr. Justice Frankfurter).

16See, e.g. 4 BLACKSTONE, COMMENTARIES (1803), 24-25;

Hawles, Remarks on the Trial of Mr. Charles Bateman, 11 Howell

State Trials 474, 476-477 (1868).

17See, e.g., COKE, THIRD INSTITUTE (1644), 6, p. 13 supra.

18See e.g., Hawles, Remarks on the Trial of Mr. Charles Bateman,

11 Howell State Trials 474, 477 (1868): “ [It] is inconsistent with

religion, as being against Charistian charity to send a great offender

quick, as it is stiled, into another world, when he is not of a capacity

to fit himself for it.”

19Ehrenzweig, A Psychoanalysis o f the Insanity Plea-Clues to the

Problems o f Criminal Responsibility and Insanity in the Death Cell,

1 CRIM. L. BULL. (No. 9) 3, 21 (1965) [hereafter cited as Ehrenz-

weig].

O h * ,

1

15

not satisfy the extreme judgment inflicted on him.20 How

ever, “ [wjhatever the reason of the law is, it is plain the

law is so.” Hawles, Remarks on the Trial of Mr. Charles

Bateman, 11 Howell State Trials 474, 477 (1816).

“When we seek the purpose of the rule we are

met with diverse explanations of varying persuasive

ness. The very multiplicity of explanations suggest

that the rule may have been devised to meet an

earlier theoretical or practical need or special con

sensus and has survived the obsolescence of the

original cause.” Hazard & Louise!!, Death, the

State, and the Insane: Stay o f Execution, 9

U.C.L.A. L. REV. 381, 383 (1962) [hereafter cited

as Death, the State, and the Insane].

Its survival, we suggest, manifests a common and unwaver

ing recognition—albeit expressed through quite wavering and

often unsatisfactory rationalizations—of Coke’s basic obser

vation that the execution of the mentally ill constitutes “a

miserable spectacle,” smacking of “extreme inhumanity and

cruelty,” supra 21

(2) The record in this proceeding concerning petitioner’s

mental condition is scant, due in part to the negligible re

sources allowed his appointed trial counsel,22 and in part

to Georgia practice which forbids a capital defendant to put

in evidence of mental impairment relevant to the question

of sentencing.23 However, enough appears, we think to

20Musselwhite v. State, 215 Miss. 363, 367, 60 So. 2d 807, 809

(1952): “it is revealed that if he were taken to the electric chair he

would not quail or take account of its significance.” See also Ehren-

zweig, at 14-15.

21See also, e.g., Hawles, Remarks from the Trial of Mr. Charles

Bateman, 11 Howell State Trials 474, 477 (1816): “ [TJhose on

whom the misfortune of madness fall, it is inconsistent with human

ity to make examples of them. . . .”

22See note 6, supra.

23A defendant may assert incompetency to be tried, and may

present evidence on that question; or he may contest guilt on the

grounds of criminal irresponsibility at the time of the offence. E.g.,

16

establish significant mental abnormality. Petitioner was diag

nosed on February 28, 1968, to be afflicted with “Mental

Deficiency, Mild to Moderate, with Psychotic Episodes asso

ciated with Convulsive Disorder,” and was found incapable

of cooperating with counsel in his defense. (App. B, p. 2b

infra.) Although this latter incapacity was found no longer

to exist on April 15, 1968, the same diagnosis was reported.

(App. B, p. 3b infra.) Petitioner was not found to be psy

chotic; and the character and extent of his condition are

not otherwise disclosed; but the record at the least reveals

grounds for the gravest doubt of his mental stability.

(3) For any man, be he mentally firm or infirm, con

demnation under a sentence of death and the “thousand

days” on death row create conditions of mind-twisting

stress.24

“He hopes by day and despairs of it by night. As

the weeks pass, hope and despair increase and

become equally unbearable. . . . He is no longer a

man but a thing waiting to be handled by the execu

tioners.” (Camus, Reflections on the Guillotine, in

CAMUS, RESISTANCE, REBELLION AND DEATH

(1961), 200-201.)25

Dr. Louis J. West has described death row as a “grisly labo

ratory [which] . . . must constitute the ultimate experimen

tal stress in which he [sic: the] condemned prisoner’s per

sonality is incredibly brutalized.”26 Dr. Isidore Zifferstein

writes that:

Rogers v. State, 128 Ga. 67, 57 S.E. 227 (1907); Summerour v. Fort-

son, 174 Ga. 862, 164 S.E. 809 (1932).

24LAWES, LIFE AND DEATH IN SING SING (1928), 161-162;

West, Medicine and Capital Punishment, in Hearings Before the Sub

committee on Criminal Laws and Procedures o f the Senate Commit

tee on the Judiciary, 90th Cong., 2d Sess., on S. 1760, To Abolish

the Death Penalty (March 20-21 and July 2, 1968) (GP.O. 1970)

[hereafter cited as Hearings], 124, 127.

2sSee also Ex parte Medley, 134 U.S. 160, 172 (1890).

26West, Medicine and Capital Punishment in Hearings, at 127.

17

“Modern techniques of execution have aimed at

minimizing the physical pain of dying (although we

do not really know how much pain is experienced

in electrocution or execution by gas). But these

modern techniques have retained to the fullest the

exquisite psychological suffering of the condemned

man.

27Zifferstein, Crime and Punishment, 1 THE CENTER MAGA

ZINE (No. 2) 84 (Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions

1968). We must admit that the published literature concerning the

psychological impact of the “thousand days” upon condemned men

is limited and unsystematic. This is one of the subjects concerning

which counsel for petitioner have, in other litigations, unsuccessfully

sought to present evidence. See Brief for Petitioner, in Aikens v.

California, supra, n. 120. The literature contains enough, however,

to glimpse the extent of the pressures upon the condemned. As exe

cution approaches, some prisoners exhibit grossly psychotic reactions,

see, e.g., ESHELMAN, DEATH ROW CHAPLAIN (1962), 159-161;

DUFFY & HIRSHBERG, 88 MEN AND 2 WOMEN (1962), 221-223,

229-230; Ehrenzweig 11, while other prisoners respond to the stress

with psychological mechanisms involving major personality distortion.

See Bluestone & McGahee, Reaction to Extreme Stress: Impending

Death by Execution, 119 AM. J. PSYCHIATRY 393 (1962).

Institutional practices on death row recognize the likelihood of

extreme reactions from the condemned, particularly suicide attempts.

“The ‘cheating of the chair’ by escape or suicide is rendered practi

cally impossible by . . . extraordinary precautions against these con

tingencies.” LAWES, LIFE AND DEATH IN SING SING (1928),

161. In Warden Lawes’ experience, these precautions cover the minu

test detail, including paring the fingernails of the condemned once

or twice a week “as long nails could be used to cut the arteries of

the wrist.” Id. at 163-164. In spite of these precautions, attempts

at suicide are not rare phenomena, id. at 163, 177, and occasionally

succeed, id., 165, 180; LAWES, TWENTY THOUSAND YEARS IN

SING SING (1932), 334; DUFFY & JENNINGS, THE SAN QUEN

TIN STORY, (1950) 108-109; ESHELMAN, DEATH ROW CHAP

LAIN (1962), 161-164. Such attempts have sometimes required sur

gical intervention to save the life of the condemned man in order

that he could be properly executed. LAWES, LIFE AND DEATH

IN SING SING (1928), 165, 177; DUFFY & HIRSHBERG, 88 MEN

AND 2 WOMEN (1962), 51-52; ESHELMAN, DEATH ROW CHAP

LAIN (1962), 164-165. See generally Gottlieb, Capital Punishment,

15 CRIME & DELINQUENCY 1, 8-10 (1969).

18

(4) Under these circumstances, we believe that a judg

ment inflicting a sentence of death upon petitioner, in the

absence of further inquiries into his mental state, subjects

him to a cruel and unusual punishment. We recognize that

in the Crumpton case28 this Court declined to hold that the

Due Process Clause required any particular form of proce

dure by which facts relevant to the sentencing decision in a

capital case could be put into the record. But the question

here is not one concerning forms of procedure: it is

whether, once facts are called to the trial court’s attention

which convey notice that its process may be unconstitu

tional, it is required by the Constitution to conduct an ade

quate inquiry into those facts. Cf. Pate v. Robinson, 383

U.S. 375 (1966). We think that it is, where the effect of

its process subjects a man who may be mentally ill not only

to the jeopardy of electrocution, but to the devastating

stresses of death row.

(5) We must also recognize, of course, that the tradi

tional Anglo-American inhibition upon the execution of the

insane has been enforced by post-conviction, non-judicial

process; and that Georgia provides a form of such process

for an inquiry into the insanity of the condemned. See Ga.

Code Ann., § 27-2602 (1970 Cum. pocket part), App. A,

p. 3a infra; Solesbee v. Balkcom, 339 U.S. 9 (1950). Pur

suant to that statute, the Governor may, in his discretion,

cause a condemned man to be mentally examined; and if

the Governor finds that he has become insane subsequent

to his conviction, the Governor may commit him to a state

hospital until his sanity is restored. When his sanity is re

stored he is returned to Court, a new death warrant for his

execution is signed, and he is executed. Ga. Code Ann.

§ 27-2604 (1953), App. A, p. 3a infra.

Solesbee sustained the constitutionality of this procedure

as a corrective against insanity supervening trial and sen-

2% Crampton v. Ohio, reported sub nom. McGautha v. California,

402 U.S. 183 (1971).

19

tence. But we do not think that its existence, or even its

constitutionality in that context, warrants a court imposing

a sentence of death upon a man of manifestly questionable

mentality without first making its own thorough inquiry

and determination whether he is competent to be put to

death and capable of receiving a death sentence.29 This is

so for two basic reasons.

First, the Georgia Governor’s'process can reprieve a con

demned man from death, but not from the torments of a

death sentence. Those torments are agonizing even for

a mind of normal stability, but may be unbearable for an

unstable one. Without adequate judicial inquiry into the

mental state of the defendant, a death sentence may be tan

tamount to a sentence of insanity.

Second, the gubernatorial reprieve merely sets in motion

a procedure by which the condemned man is hospitalized

and healed enough to kill. Georgia’s insistence upon exe

cuting a condemned man following his restoration to sanity

is consistent with prevailing American practice.30 It is, how

ever, a plain barbarity which the Eighth Amendment should

condemn. In England, at least since 1840, “there has been

no case where a prisoner has been executed after being cer

tified insane under the statute in force at the time.”31 In

principle as well as in fact, the Royal Commission found:

“. . . If a prisoner under sentence of death is cer

tified insane and removed to Broadmoor, it is

unthinkable that the sentence should ever be car

ried out in the event of his recovery. . . ,”32

29See also Nobles v. Georgia, 168 IJ.S. 398 (1897); Phyle v. Duffy,

334 U.S. 431 (1948); Caritativo v. California, 357 U.S. 549 (1958).

30w e ih o f e n , m e n t a l d is o r d e r a s a c r im in a l d e

f e n s e (1954) 468-470; Death, the State, and the Insane 382-383;

Ehrenzweig 11.

31 ROYAL COMMISSION 128.

32ROYAL COMMISSION 157-158. See also Feltham, The Com

mon Law and the Execution o f Insane Criminals, 4 MELBOURNE

U.L. REV. 434, 475 (1964): “if such a medical inquiry finds a priso-

20

A judicial sentence of death imposed upon a man in the

same condition—or for want of inquiry upon notice that he

may be in the same condition—seems to us equally unthink

able. It is no less so because thereafter, by executive grace,

he may be permitted to vacillate between insanity and

death’.

CONCLUSION

The death sentence imposed upon petitioner William

Henry Furman should be set aside as a cruel and unusual

punishment.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

JACK HIMMELSTEIN

ELIZABETH B. DuBOIS

JEFFRY A. MINTZ

ELAINE R. JONES

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

B. CLARENCE MAYFIELD

910 West Broad Street

Savannah, Georgia 31401

MICHAEL MELTSNER

Columbia University Law School

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

A tto rn e y s fo r Petitioners

ner insane; there should be a mandatory duty upon the executive to

reprieve. This, although not required by law, has been the invariable

practice in England since 1840 and is no more than common decency

and humanity requires.”

A-i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

APPENDICES

Page

Statutory Provisions:

Ga. Code Ann., § 26-1001 (1953 Rev. vol.)................................. la

Ga. Code Ann., § 26-1002 (1953 Rev. vol. ) .............................. la

Ga. Code Ann., § 26-1005 (1970 Cum. pocket p a rt) .................. la-2a

Ga. Code Ann., § 26-1009 (1953 Rev. vol.)................................. 2a

Ga. Code Ann., § 27-2512 (1953 Rev. vol.)................................. 2a-3a

Ga. Code Ann., § 27-2602 (1970 Cum. pocket p a rt) .................. 2a

Ga. Code Ann., § 27-2604 (1953 Rev. vol.)................................. 3a-4a

Ga. Crim. Code, § 26-1101 (1970 Rev. v o l . ) .............................. 4a

Ga. Crim. Code, § 26-3102 (1970 Rev. v o l . ) .............................. 4a-5a

la

APPENDIX A

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

Ga. Code Ann., § 26-1001

(1953 Rev. vol.)

effective prior to July 1, 1969

26-1001. (59 P.C.) Definition; kinds.—Homicide is the

killing of a human being, and is of three kinds—murder,

manslaughter, and justifiable homicide. (Cobb, 783.)

Ga. Code Ann., § 26-1002

(1953 Rev. vol.)

effective prior to July 1, 1969

26-1002. (60 P.C.) Murder defined.—Murder is the un

lawful killing of a human being, in the peace of the State,

by a person of sound memory and discretion, with malice

aforethought, either express or implied. (Cobb, 783.)

Ga. Code Ann. § 26-1005

(1970 Cum. pocket part)

effective prior to July 1, 1969

26-1005. (63 P.C.) Punishment for murder; recommen

dation by jury.—The punishment for persons convicted of

murder shall be death, but may be confinement in the pen

itentiary for life in the following cases: If the jury trying

the case shall so recommend, or the the conviction is founded

solely on circumstantial testimony, the presiding judge may

sentence to confinement in the penitentiary for life. In the

former case it is not discretionary with the judge; in the

latter it is. When it is shown that a person convicted of

murder had not reached his 17th birthday at the time of

the commission of the offense, the punishment of such per

son shall not be death but shall be imprisonment for life.

Whenever a jury, in a capital case of homicide, shall find

a verdict of guilty, with a recommendation of mercy, instead

of a recommendation of imprisonment for life, in cases

2a

where by law the jury may make such recommendation,

such verdict shall be held to mean imprisonment for life.

If, in any capital case of homicide, the jury' shall make any

recommendation, where not authorized by law to make a

recommendation of imprisonment for life, the verdict shall

be construed as if made without any recommendation.

(Cobb, 783. Acts 1875, p. 106; 1878-9, p. 60; 1963, p. 122.)

Ga. Code Ann., § 26-1009

(1953 Rev. vol.)

effective prior to July 1, 1969

26- 1009. (67 P.C.) Involuntary manslaughter defined.—

Involuntary manslaughter shall consist in the killing of a

human being without any intention to do so, but in the

commission of an unlawful act, or a lawful act, which prob

ably might produce such a consequence, in an unlawful

manner: Provided, that where such involuntary killing shall

happen in the commission of an unlawful act which, in its

consequences, naturally tends to destroy the life of a human

being, or is committed in the prosecution of a riotous

intent, or of a crime punishable by death or confinement

in the penitentiary, the offense shall be deemed and

adjudged to be murder. (Cobb, 784.)

Ga. Code Ann., § 27-2512

(1953 Rev. vol.)

27- 2512. Electrocution substituted for hanging; place of

execution.—All persons who shall be convicted of a capital

crime and who shall have imposed upon them the sentence

of death, shall suffer such punishment by electrocution

instead of by hanging.

In all cases in which the defendant is sentenced to be

electrocuted it shall be the duty of the trial judge, in pass

ing sentence, to direct that the defendant be delivered to

the Director of Corrections for electrocution at such penal

institution as may be designated by said Director, However,

no executions shall be held at the old prison farm in Bald-

3a

win county. (Acts 1924, pp. 195, 197; Acts 1937-38, Extra

Sess., p. 330.)

Ga. Code Ann., § 27-2602

(1970 Cum. Pocket part)

27-2602. (1074 P.C.) Disposition of insane convicts.

Cost of investigations.—Upon satisfactory evidence being

offered to the Governor, showing reasonable grounds to

believe that a person convicted of a capital offense has

become insane subsequent to his conviction, the Governor

may, in his discretion, have said person examined by such

expert physicians as the Governor may choose, the cost of

said examination to be paid by the Governor out of the

contingent fund. It shall be the responsibility of the Gover

nor to cause said physicians to receive written instructions

which plainly set forth the legal definitions of insanity as

recognized by the laws of this State, and said physician shall,

after making the necessary examination of the prisoner,

report in writing to the Governor whether or not reasona

ble grounds exist to raise an issue that the prisoner is insane

by the standards previously specified to them by the Gover

nor. The Governor may, if he shall determine that the per

son convicted has become insane, have the power of com

mitting him to the Milledgeville State Hospital until his san

ity shall have been restored or determined by laws now in

force. (Acts 1903, p. 77; 1960, pp. 988, 989.)

Ga. Code Ann., § 27-2604

(1953 Rev. vol.)

27-2604. (1076 P.C.) Resentence and warrant on recov

ery of convict.—If the convict mentioned in the preceding

section should recover, the fact shall be at once certified by

the superintendent of the Milledgeville State Hospital to the

judge of the court in which the conviction occurred. When

ever it shall appear to the judge by said certificate, or by

inquisition or otherwise, that the convict has recovered and

is of sound mind, he shall have the convict removed to the

4a

jail of the county in which the conviction occurred, or to

some other safe jail, and shall pass sentence, either in term

time or vacation, upon the convict, and he shall issue a new

warrant, directing the sheriff to do execution of the sen

tence at such time and place as may be named in the war

rant, which the sheriff shall be bound to do accordingly.

The judge shall cause the new warrant, and other proceed

ings in the case, to be entered on the minutes of said super

ior court. (Acts 1874, p. 30.)

Ga. Crim. Code, § 26-1101

(1970 Rev. vol.)

(effective July 1, 1969)

26-1101. Murder.—(a) A person commits murder when

he unlawfully and with malice aforethought, either express

or implied, causes the death of another human being.

Express malice is that deliberate intention unlawfully to take

away the life of a fellow creature, which is manifested by

external circumstances capable of proof. Malice shall be

implied where no considerable provocation appears, and

where all the circumstances of the killing show an aban

doned and malignant heart.

(b) A person also commits the crime of murder when in

the commission of a felony he causes the death of another

human being, irrespective of malice.

(c) A person convicted of murder shall be punished by

death or by imprisonment for life.

(Acts 1968, pp. 1249, 1276.)

Ga. Crim. Code § 26-3102

(1970 Rev. vol.)

effective July 1, 1969

26-3102. Capital offenses—jury verdict and sentence.—

Where, upon a trial by jury, a person is convicted of an

offense which may be punishable by death, a sentence of

death shall not be imposed unless the jury verdict includes

a recommendation that such sentence be imposed. Where

5a

a recommendation of death is made, the court shall sen

tence the defendant to death. Where a sentence of death

is not recommended by the jury, the court shall sentence

the defendant to imprisonment as provided by law. Unless

the jury trying the case recommends the death sentence in

its verdict, the court shall not sentence the defendant to

death. The provisions of this section shall not affect a sen

tence when the case is tried without a jury or when the

judge accepts a plea of guilty.

(Acts 1968, pp. 1249, 1335; 1969, p. 809.)

lb

APPENDIX B

PSYCHIATRIC REPORTS

Pursuant to petitioner’s commitment for a pretrial men

tal examination in this case (A. 8), the following two letters

were written by the Superintendent of the Georgia Central

State Hospital to the trial court below. They were subse

quently made a part of the record of the trial court by

express written order;lb and petitioner’s notice of appeal

requested the clerk to transmit the entire record to the

Georgia Supreme Court.2b However, for reasons unknown

to us, the clerk of the trial court neglected to transmit the

letters as a part of the appellate record; and they were not

before the Georgia Supreme Court. Subsequent to this

Court’s order granting certiorari, petitioner’s counsel noticed

their absence and asked the clerk of the Chatham County

Supreme Court to certify the records of the Georgia

Supreme Court. The clerk did so; whereupon the clerk of

the Georgia Supreme Court transmitted them to this Court

under certification reciting that they were not a part of the

record in the Georgia Supreme Court.

Under these circumstances, we think that the letters are

properly a part of the record upon which this Court may

consider the case. Petitioner did all that he was required

to do in order to include them in the appellate record, and

is not responsible for the clerk’s neglect. The authenticity

of the letters cannot be questioned; they are a part of the

trial court record; and their absence from the record before

the Georgia Supreme Court did not affect the course of the

litigation in any way. That court’s decision of the Eighth

Amendment question was perfunctory in any event, since

lbOrder, dated February 20, 1969 (R. 44): “FURTHER

ORDERED that the Psychiatric Report of the Movant WILLIAM

HENRY FURMAN be and is made a part of this record.”

2bNotice of Appeal, dated March 3, 1969 (R.l): “The clerk will

please include the entire record on appeal.”

2b

the question was foreclosed by—and decided summarily on

authority of—several prior Georgia decisions.

* * *

STATE OF GEORGIA

CENTRAL STATE HOSPITAL

MILLEDGEVILLE, GEORGIA 31062

February 28, 1968

Honorable Dunbar Harrison

Judge, Superior Court

Eastern Judicial Circuit

c/o Courthouse

Savannah, Georgia

Re: William Henry Furman

Case No: 157 086

Binion 4

Dear Judge Harrison:

The above named patient was admitted to this hospital

on October 26, 1967, by Order of your Court.

The patient was presented to a staff meeting today, Feb

ruary 28, 1968. It was the unanimous opinion of the mem

bers of the staff, Dr. Elpidio Stincer, Dr. Jose Mendoza, and

Dr. Armando Gutierrez, that this patient should retain his

present diagnosis of Mental Deficiency, Mild to Moderate,

with Psychotic Episodes associated with Convulsive Disor

der.

It was also agreed that at present the patient is not psy

chotic, but he is not capable of cooperating with his coun

sel in the preparation of his defense.

We feel at this time that he is in need of further psychia

tric hospitalization and treatment. He will be reevaluated

at a later date and presented to the staff again for a deci-

3b

sion as to his final disposition. We will notify you of the

results of that meeting.

Yours very truly,

N

James B. Craig, M.D.

Superintendent

By: E. Stincer, M.D.

Senior Staff Physician

ES:jfh

STATE OF GEORGIA

CENTRAL STATE HOSPITAL

MILLEDGEVILLE, GEORGIA 31062

April 15, 1968

Honorable Dunbar Harrison

Judge, Superior Courts [sic]

Eastern Judicial Circuit

c/o Courthouse

Savannah, Georgia

Re: William Henry Furman

Case No. 157 086

Binion 4

Dear Judge Harrison:

The above named patient was admitted to this hospital

on October 26, 1967 by Order of your Court.

An evaluation has been made by our staff and a diagno

sis of Mental Deficiency, Mild to Moderate, with Psychotic

Episodes associated with Convulsive Disorder, was made. It

is felt that he is not psychotic at present, knows right from

wrong and is able to cooperate with his counsel in prepar

ing his defense.

4b

It is recommended that he be returned to the court for

disposition of the charges pending against him. Please have

a duly authorized person to call for him at your earliest

convenience.

Yours very truly,

/s /

James B. Craig, M.D.

Superintendent

By: E. Stincer, M.D.

Senior Staff Physician

ES:jfh

CC: Hon. Andrew Joe Ryan, Jr.

Solicitor General

Hon. Carl A. Griffin

Sheriff, Chatham County