Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, VA Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 4, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, VA Brief for Appellees, 1968. 03e24792-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3e2b0de1-01c0-4f07-b703-7bd296a7766b/allen-v-county-school-board-of-prince-edward-county-va-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

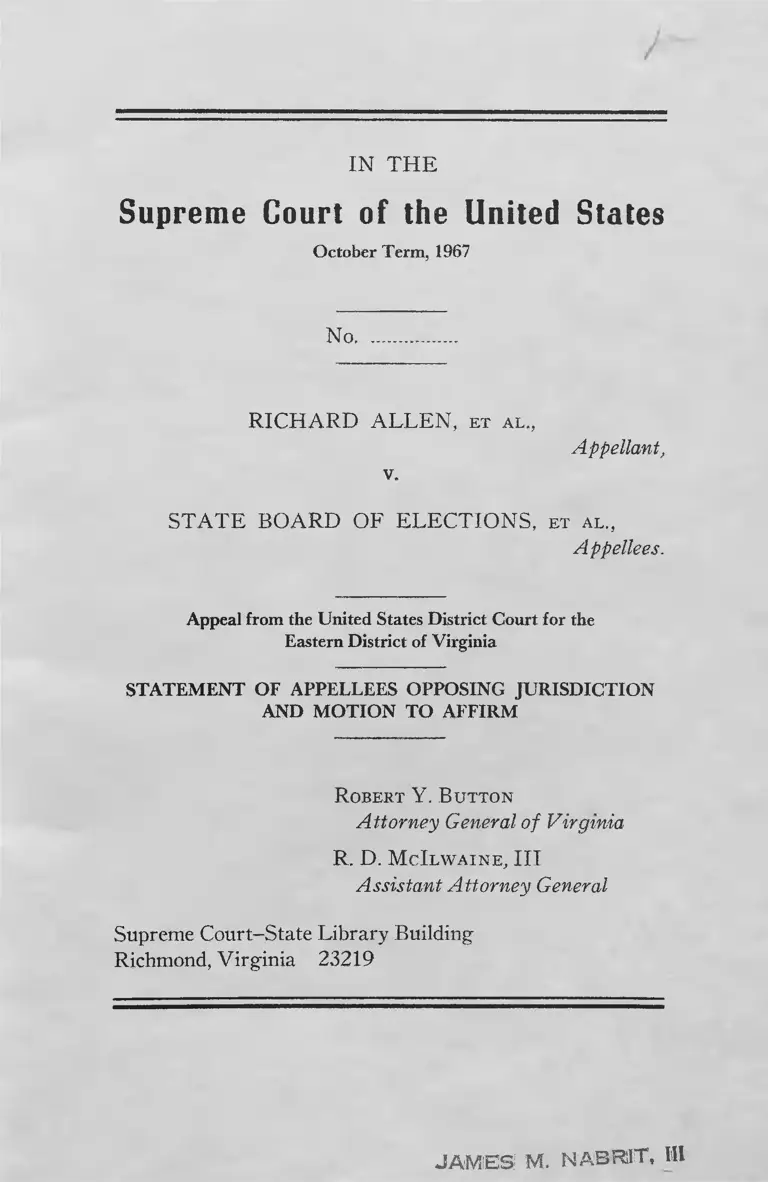

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1967

No.

RICHARD ALLEN, et a l .,

Appellant,

v.

STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS, et a l .,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia

STATEMENT OF APPELLEES OPPOSING JURISDICTION

AND MOTION TO AFFIRM

R obert Y. B utton

Attorney General of Virginia

R. D. M cI l w a in e , I I I

Assistant Attorney General

Supreme Court-State Library Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

JAMES M. NABRlT, HI

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

P r e l im in a r y S t a t e m e n t ............................................................................. 1

P rior P r o c e e d in g s ........................................................................................... 2

S t a t e m e n t Of F acts ............................................................................. 3

S ta tu tes I nvolved ................. 6

Q u estio n P r e s e n t e d ...................................................................................... 7

A r g u m en t .......................................................... 7

Section 24-252 Of The Virginia Code Is Not Violative Of The

Fourteenth Amendment To The Constitution Of The United

States Or The Voting Rights Act Of 1965 ................................. 7

Co n c lu sio n ........................................................................................ 13

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Allen v. State Board of Elections, 268 F. Supp. 218....................... 3

Blackman v. Stone, 7 Cir., 101 F. (2d) 500 ............. ..... -.............. 10

Fletcher v. Wall, 172 111. 426, 50 N.E. 230 .... ..... ................ ....... 10

McSorley v. Schroeder, 196 111. 99, 63 N.W. 697 .......................... 10

Roberts v. Quest, 173 111. 427, 50 N.E. 1073 ................................. 10

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 ...............................~ 7

Other Authorities

Code of Virginia (1950) :

Section 24-251 ........................................................................ 5, 6, 8

Page

Section 24-252.................................................................... 2, 6, 7, 9

Constitution of the United States:

Fourteenth Amendment............................................................ 2, 12

28 U.S.C.A., Sections 1331 and 1343(3), (4) ................................. 2

28 U.S.C.A., Sections 2281 and 2284 .............................................. 2

42 U.S.C.A., Section 1973 et se q ....................................-..... ....... 2, 11

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1967

No.

RICHARD ALLEN, et a l .,

v.

Appellant,

STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS, e t a l .,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia

STATEMENT OF APPELLEES OPPOSING JURISDICTION

AND MOTION TO AFFIRM

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

By letter of the Honorable John F. Davis, Clerk of the

Supreme Court of the United States, dated December 5,

1967, the Attorney General of Virginia was requested to

file a response to the appeal taken from an order of the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Virginia denying appellants’ request for injunctions and

dismissing their complaint. In accordance with the request

2

contained in the above-mentioned communication,* written

by the Clerk at the direction of this Court, the within re

sponse is filed. The appellees, believing the matters set forth

herein will demonstrate the lack of substance in the ques

tions sought to be presented by this appeal, file this state

ment in opposition to appellees’ jurisdictional statement and

include their motion to affirm the judgment of the court

below upon the ground that the question on which the deci

sion of this cause depends is so unsubstantial as to obviate

further argument.

PRIOR PROCEEDINGS

On November 26, 1966, appellants instituted in the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Virginia this suit for preliminary and permanent injunc

tions allegedly to restrain the enforcement, operation and

execution of Section 24-252 of the Code of Virginia (1950)

by restraining the defendant election officials and their suc

cessors in office from failing or refusing to count, and from

requiring or permitting any other election officials to fail

or refuse to count, any vote hereafter given for any person

solely because the name of such person was inserted on the

official ballot otherwise than in the handwriting of the

voter.

Jurisdiction was invoked under 28 U.S.C.A. 1331 and

1343(3), (4) ; the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C.A.

1973 et seq.; the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States and 28 U.S.C.A. 2281 and 2284—

the latter two statutes providing for the convening of a

District Court of three judges to hear and determine suits

in which restraint of the enforcement of a State statute,

* Post, Appendix A.

3

upon the ground of such statute’s constitutionality, is

sought.

A District Court of three judges having been designated

by the Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit, the matter was heard on the merits

on April 11, 1967. Subsequently, the District Court rendered

its opinion denying the prayer of appellants’ complaint and

dismissing the suit. See, Allen v. State Board of Elections,

268 F. Supp. 218. On May 2, 1967, a final order effectuating

this opinion was entered. Jurisdictional Statement, Ap

pendix, p. 9 a.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Plaintiffs are citizens of the Commonwealth of Virginia

registered to vote in one of the precincts or wards of one of

the several counties and cities comprising the Fourth Con

gressional District of Virginia. Defendants are the State

Board of Elections of the Commonwealth of Virginia and

various individuals who were, on November 8, 1966, either

judges or clerks of election in certain precincts located in

Greenville County, Cumberland County and Powhatan

County, Virginia.

Plaintiffs allege that, at the general election held on

November 8, 1966, they were furnished official ballots on

which were printed the names of two candidates for election

to the House of Representatives of the United States from

the Fourth Congressional District of Virginia. They further

allege (1) that they inserted the name “S. W. Tucker” on

the official ballot, immediately under the names of the two

candidates printed thereon, by pasting on the official ballot

a sticker or paster upon which the name “S. W. Tucker”

had been printed and (2) that they made a check, cross mark

or line on the ballot immediately preceding the name thus

inserted and thereafter deposited such ballots in the ballot

4

boxes. The ballots thus altered or marked were not officially

counted or included in the official returns as votes validly

cast for the said S. W. Tucker.

On August 6, 1965, the Voting Rights Act of 1965

(Public Law 89-110, 79 Stat. 437) enacted by the Congress

of the United States became effective in Virginia. This Act

had the effect of suspending literacy tests and similar voting

qualifications throughout the Commonwealth for a specified

period by prescribing that no person might be denied the

right to vote in any election because of his failure to comply

with a “test or device” as defined by the statute. As used

throughout the Act, the phrase “test or device” means any

requirement that a registrant or voter must (1) demon

strate the ability to read, write, understand, or interpret any

matter, (2) demonstrate any educational achievement or his

knowledge of any particular subject, (3) possess good moral

character, or (4) prove his qualifications by the voucher

of registered voters or members of any class.

On August 12, 1965—within a week of the effective date

(August 6, 1965) of the Voting Rights Act of 1965—

the Honorable Levin Nock Davis, Secretary of the de

fendant State Board of Elections, sent to all registrars of

the Commonwealth of Virginia a bulletin advising them

that the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was in force in Virginia

and that use of the Virginia registration form in the manner

formerly required by Virginia law was prohibited. The

above-mentioned bulletin contained the following instruc

tions :

“The Registrar shall review the forms in the pres

ence of the applicant to insure that all questions are

answered clearly and completely. If all questions are

not answered clearly and completely, or if the applicant

is not able personally to complete the forms in whole or

in part because of lack of literacy or otherwise, or has

5

difficulty in doing so, the Registrar shall orally examine

the applicant and record the pertinent information on

the forms or otherwise assist the applicant in com

pleting the forms. After the forms are completed, the

Registrar shall require the applicant to take an oath or

affirmation as to the truth of the answers and to sign

his name or make his mark thereon.”

Subsequently, on October 15, 1965 Mr. Davis also sent

to the general registrars and the secretaries of the various

electoral boards throughout the Commonwealth—to be de

livered by the latter to all judges of election—a further

bulletin which informed and instructed all judges of election

that:

“On August 6, 1965, the ‘Voting Rights Act of

1965’ enacted by the Congress of the United States

became effective and is now in force in Virginia. Under

the provisions of this Act, any person qualified to vote

in the General Election to be held November 2, 1965,

who is unable to mark or cast his ballot, in whole or

in part, because of a lack of literacy ( in addition to any

of the reasons set forth in Section 24-251 of the Vir

ginia Code) shall, if he so requests, be aided in the

preparation of his ballot by one of the judges of elec

tion selected by the voter. The judge of election shall

assist the voter, upon his request, in the preparation of

his ballot in accordance with the voter’s instructions,

and shall not in any manner divulge or indicate, by

signs or otherwise, the name or names of the person or

persons for whom any voter shall vote.

“These instructions also apply to precincts in which

voting machines are used.”

The instructions contained in the above-mentioned bulle

tins continue in full force in the Commonwealth so long as

the Voting Rights Act of 1965 remains effective in Virginia.

6

THE STATUTES INVOLVED

Under consideration in the instant proceedings are Sec

tions 24-251 and 24-252 of the Code of Virginia (1950)

as amended which provide:

“§ 24-251.—Any person registered prior to the

first of January, nineteen hundred and four, and any

person registered thereafter who is physically unable

to prepare his ballot without aid, may, if he so requests,

be aided in the preparation of his ballot by one of the

judges of election designated by himself, and any per

son registered, who is blind, may if he so requests, be

aided in the preparation of his ballot by a person of

his choice. The judge of election, or other person, so

designated shall assist the elector in the preparation of

his ballot in accordance with his instructions, but the

judge or other person shall not enter the booth with

the voter unless requested by him, and shall not in any

manner divulge or indicate, by signs or otherwise, the

name or names of the person or persons for whom any

elector shall vote. For a corrupt violation of any of the

provisions of this section, the person so violating shall

be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor and be confined in

jail not less than one nor more than twelve months.”

“§ 24-252.—At all elections except primary elections

it shall be lawful for any voter to place on the official

ballot the name of any person in his own handwriting

thereon and to vote for such other person for any office

for which he may desire to vote and mark the same by

a check (V) or cross (X or -j-) mark or a line (—)

immediately preceding the name inserted. Provided,

however, that nothing contained in this section shall

affect the operation of § 24-251 of the Code of Virginia.

No ballot, with a name or names placed thereon in vio

lation of this section, shall be counted for such person.”

7

QUESTION PRESENTED

Is Section 24-252 of the Virginia Code violative of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States or the Voting Rights Act of 1965 ?

ARGUMENT

Section 24-252 Of The Virginia Code Is Not Violative Of The

Fourteenth Amendment To The Constitution Of The United

States Or The Voting Rights Act Of 1965.

In the instant case, it is important to realize at the outset

that the Virginia statute under attack by appellants—Sec

tion 24-252 of the Virginia Code—has been superseded by

the Voting Rights Act of 1965. With the advent of the

Voting Rights Act, which suspended in Virginia any re

quirement that a voter be able to read, write or understand

any matter in registering to vote or in voting, the require

ment of Section 24-252 that the inserted name of a “write-

in” candidate be in the handwriting of the voter was super

seded and was no longer enforceable or enforced in Virginia.

Equally important is it to realize that the above-stated

propositions were conceded by appellees in this case from

the beginning, and no attempt whatever was made to assert

the efficacy of the challenged enactment in this regard. On

the contrary, appellees established in evidence and empha

sized in argument that within a week of the effective date of

the Voting Rights Act of 1965—and before the case of

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U. S. 301, was even

instituted in this Court—the defendant State Board of

Elections issued a bulletin instructing all registrars to

register all persons who were unable themselves to register

because of a lack of literacy. Ante, p. 4. The language in

which this bulletin was couched was transposed almost ver

batim from the Federal regulations implementing the Vot-

8

ing Rights Act, and the substantial identity of language

clearly indicates that every effort was made to conform the

applicable Virginia law precisely to the requirements of the

Federal statute. See, Appendix B, post. In addition, on

October 15, 1965—some three weeks before the first general

election held in Virginia after the effective date of the Vot

ing Rights Act—the defendant State Board of Elections

sent to all general registrars and to all secretaries of the

various local electoral boards for transmittal to all judges

of elections, a further bulletin instructing all judges of

elections to render assistance to any voter who was unable

to mark or cast his ballot, in whole or in part, because of a

lack of literacy. Ante, p. 5. As the District Court noted,

the instructions contained in these bulletins continue in full

force in the Commonwealth so long as the Voting Rights

Act of 1965 remains effective in Virginia. Jurisdictional

Statement, Appendix, p. 7a.

Despite the requirement of the challenged statute that

the inserted name of a “write-in” candidate be placed on the

ballot in the handwriting of the voter, provision is made,

by the reference to Section 24-251 of the Virginia Code—

for the assistance of physically handicapped voters by the

judges of election, who are (1) authorized by the latter

provision to assist a physically handicapped voter “in the

preparation of his ballot in accordance with” the instruc

tions of the voter and (2) forbidden, under penal sanction,

from divulging or indicating in any manner, by sign or

otherwise, the name or names of the persons for whom any

physically handicapped voter cast his ballot. When the

Voting Rights Act of 1965 became effective in Virginia,

the provisions of Section 24-251 of the Virginia Code were

broadened by the instructions of the State Board of Elec

tions to include the educationally handicapped as well as

9

the physically handicapped within the provisions permitting

assistance, and thus render Virginia law consistent with the

commands of the Federal statute. These instructions of the

State Board of Elections removed from the operative Vir

ginia law any requirement that a person be able to comply

with any “test or device” as defined in the Voting Rights

Act.

In light of the foregoing, appellants cannot assert, and

did not assert, that they are now required to be able to

read or write in order to vote in Virginia, or that they

are denied the right to vote for failure to comply with any

test or device. With particular reference to the questions

presented in the case at bar, Virginia law does not permit

stickers or pasters to be utilized by voters in casting or

marking their ballots under any circumstances, regardless

of the physical or educational condition of the individual

voter. In this connection, appellants assert that Section 24-

252 of the Virginia Code—to the extent that it forbids them

to utilize stickers or pasters in casting their ballots—in

fringes rights secured to them by the Fourteenth Amend

ment and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Initially in this connection, it is significant that no case

supportive of appellants’ contention can be found. As the

District Court pointed out (Jurisdictional Statement, Ap

pendix, p. 3a) :

“The plaintiffs’ contention that Section 24-252 vio

lates the Fourteenth Amendment because it discrimi

nates against illiterates is not supported by authority.”

However, as the District Court also noted, there is no want

of authority upon this point, and decisions sustaining and

justifying a legislative determination to forbid the use of

stickers or pasters are legion. In this connection, the District

10

Court observed (Jurisdictional Statement, Appendix, p.

3a) :

“The propriety of stickers is a matter for legisla

tive, not judicial determination. Arguments for and

against their use abound. Stickers heme been lauded for

facilitating voting and denounced as conducive to

fraud and confusion. Their use has been approved

under statutes permitting write-ins. Pace v. Hickey,

236 Ark. 792, 370 S.W. 2d 66 (1963); O’Brien v.

Board of Elections Comm’rs, 257 Mass. 332, 153 N.E.

553 (1926) ; Dewalt v. Bartley, 146 Pa. 529, 24 A. 185,

15 L.R.A. 771 (1892) ; State on Complaint of Tank v.

Anderson, 191 Wis. 538, 211 N.W. 938 (1927). Illi

nois forbade their use, Fletcher v. Wall, 172 111. 426,

50 N.E. 230, 40 L.R.A. 617 (1898), and the constitu

tionality of this ban has been upheld. Blackman v.

Stone, 101 F. 2d 500, 504 (7th Cir. 1939). (Italics

supplied.)

Squarely in point is the decision of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in Blackman v.

Stone, 7 Cir., 101 F. (2d) 500. That case was a class action

by certain residents of Illinois challenging various provi

sions of the election laws of that State. In a series of de

cisions, the Supreme Court of Illinois had held that the use

of stickers or pasters by voters was forbidden. See, Mc-

Sorley v. Schroeder, 196 111. 99, 63 N.W. 697; Roberts v.

Quest, 173 111. 427, 50 N. E. 1073; Fletcher v. Wall, 172

111. 426, 50 N.E. 230. In the Blackman case, plaintiffs con

tended, inter alia, that this provision of the Illinois law was

violative of the Fourteenth Amendment. Rejecting this con

tention the Court declared (101 F. (2d) at 504) :

“It is further contended by appellants that section

288 of the law is invalid because it requires all voters

11

to vote by printed ballots furnished by the State and

forbids the use of other ballots or pasters. There is no

merit in this contention. The section is a reasonable ex

pression of the will of the Illinois Legislature, and is

not in any manner inconsistent with any provision of

the Federal Constitution. (Italics supplied.)

Equally manifest is it that the statute in question in

fringes no right secured to the appellants by the Voting

Rights Act of 1965. In light of the present status of the

election laws of the Commonwealth, previously emphasized

in this brief, it cannot be denied that Virginia law now

makes ample provision for the educationally handicapped

voter to register and cast his ballot. Precisely in this con

nection, the District Court declared (Jurisdictional State

ment, Appendix, pp. 5a, 7a) :

“No evidence has been presented that Virginia’s

prohibition of stickers has been administered in a dis

criminatory manner. It has not been used to disfran

chise any class of citizens.

* * *

“The requirement that a write-in candidate’s name

be inserted in the voter’s handwriting is not a test

or device defined in 42 U.S.C. § 1973b(c). The re

quirement did not preclude the plaintiffs from register

ing or from voting. Under present Virginia statutes

and regulations of the Board of Elections, an illiterate

can cast a valid write-in ballot by enlisting the assist

ance of a judge of election. No evidence was offered

that any judge of election denied any illiterate voter the

confidential assistance to which he is entitled.” (Italics

supplied.)

It is thus unarguably apparent that no citizen of Virginia,

otherwise qualified to vote, is denied the right to vote in any

election held in the Commonwealth because of his failure

12

to comply with any “test or device” as defined in the Voting

Rights Act of 1965. Indeed, it is clear that the election laws

of Virginia as interpreted and applied by the defendant

State Board of Elections since the Voting Rights Act of

1965 became operative in the Commonwealth are fully con

sistent with all requirements of Federal law.

Essentially in this litigation, appellants assert that they

have the right to select the means which they will employ to

vote for a “write-in” candidate (i.e., by use of pasters or

stickers) regardless of whether or not Virginia law au

thorizes this method of voting. Apparently, the right exists

only in Virginia, for it is clear from the decisional author

ities cited by the District Court that the propriety of utilizing

stickers or pasters in this fashion is a matter for legislative

determination by each State, and statutes of other States

barring use of stickers or pasters are not subject to consti

tutional objection. Thus, as a constitutional proposition at

least, appellants’ assertion necessarily entails a determina

tion that the Fourteenth Amendment guarantees education

ally handicapped voters in Virginia a right which it does

not equally secure to educationally handicapped voters in

other States.

Implicit in appellants’ position is the contention that the

right to vote by means of stickers or pasters is a right

guaranteed them by the Fourteenth Amendment and the

Voting Rights Act of 1965. It is perfectly clear from the

decisions of this Court, however—as the District Court

pointed out—that the Fourteenth Amendment, per se, does

not even guarantee an illiterate person the right to vote at

all, much less to vote by a method of his own choosing.

Moreover, there is obviously nothing in the Voting Rights

Act of 1965 or any of its implementing regulations which

even remotely suggests that this method of voting is even

permissible, much less required, by the Federal statute.

13

Counsel for appellees submit that the provisions of Vir

ginia law under attack in the instant case abridge no federal

ly protected right of the appellants. Quite to the contrary,

Virginia law treats with perfect equality all citizens of the

Commonwealth, otherwise qualified to vote, who are unable

to cast their ballots in their own handwriting, whether such

inability is occasioned by a physical or an educational disabil

ity. Surely, a statute which makes such even-handed provi

sion for remedying the deficiencies confronting physically

or educationally disabled voters cannot be violative of either

the Fourteenth Amendment or the Voting Rights Act of

1965.

CONCLUSION

In light of the foregoing, counsel for appellees submit

that the question upon which the decision in this case

depends is so unsubstantial as to obviate further argument

and that the judgment of the District Court should be

affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

R obert Y. B u tton

Attorney General of Virginia

R. D. M cI l w a in e , III

Assistant Attorney General

Supreme Court-State Library Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, R. D. McIlwaine, III, an Assistant Attorney General

of Virginia, a member of the Bar of the Supreme Court of

the United States and one of the counsel for appellees in

14

the above-captioned matter, hereby certify that copies of this

Statement of Appellees Opposing Jurisdiction and Motion

to Affirm have been served upon each of counsel of record

for the parties herein by depositing the same in the United

States Post office, with first-class postage prepaid, this

4th day of January, 1968, pursuant to the provisions of Rule

33(1) of the Rules of the Supreme Court of the United

States, as follows: Jack Greenberg, Esq. and James M.

Nabrit, III, Esq., 10 Columbus Circle, New York, New

York 10019, and Oliver W. Hill, Esq., S. W. Tucker, Esq.,

Henry L. Marsh, III, Esq., and Harold M. Marsh, Esq.,

214 East Clay Street, Richmond, Virginia 23219, counsel

for appellants

Assistant Attorney General

15

APPENDIX “A”

OFFICE OF THE CLERK

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

WASHINGTON, D. C. 20543

December 5, 1967

The Honorable Robert Y. Button

Attorney General of Virginia

Supreme Court Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

R E : A l le n e t a l ., v. S ta te B oard of

E l ec tio n s et a l .

No. 661, October Term, 1967

Dear Sir :

An appeal was filed in this Court on September 28, 1967,

in the above-entitled case, and my records indicate that you

were served with a copy of the jurisdictional statement.

I have been directed by the Court to request that you

file a response in this case. Such a response usually takes the

form of a motion to dismiss or affirm. Forty printed copies

of such a motion, together with proof of service thereof,

should reach this office on or before January 4, 1968.

On December 4 the Court entered an order inviting the

Solicitor General to file a brief expressing the views of the

United States in this case.

Very truly yours,

J o h n F. D avis, Clerk

By / s / E. P. Cu l l in a n

E. P. Cullinan

Chief Deputy.

EPC:jmh

cc: Jack Greenberg, Esq.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

APPENDIX “B”

F ederal R egister

V o l u m e 30—N u m b er 152

August 7, 1965

Title 45—Chapter 8

C iv il S erv ice Co m m issio n

P art 801—V o tin g R ig h t s P rogram

§ 801.203. Procedures for filing application.

(a) An applicant may obtain an application at the place

and during the times set out in Appendix A for the appro

priate political subdivision. An application may be completed

only at the place where it was obtained and shall be sub

mitted by the applicant in person to an examiner at that

place.

(b) An examiner shall review the application in the

presence of the applicant to insure that all questions are

answered clearly and completely. If all questions are not

answered clearly and completely or if an applicant is not

able personally to complete the application in whole or in

part because of lack of literacy or otherwise, or has dif

ficulty in doing so, an examiner shall orally examine the ap

plicant and record the pertinent information on the applica

tion or otherwise assist the applicant in completing the

application.

(c) After an application is completed, an examiner shall

require the applicant to take the oath or affirmation pre

scribed on the application and to sign his name or make his

mark thereon.