Jackson v. Georgia Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

August 25, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jackson v. Georgia Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amici Curiae, 1971. efcba204-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3e355e1a-c514-4128-904a-235bbec46431/jackson-v-georgia-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

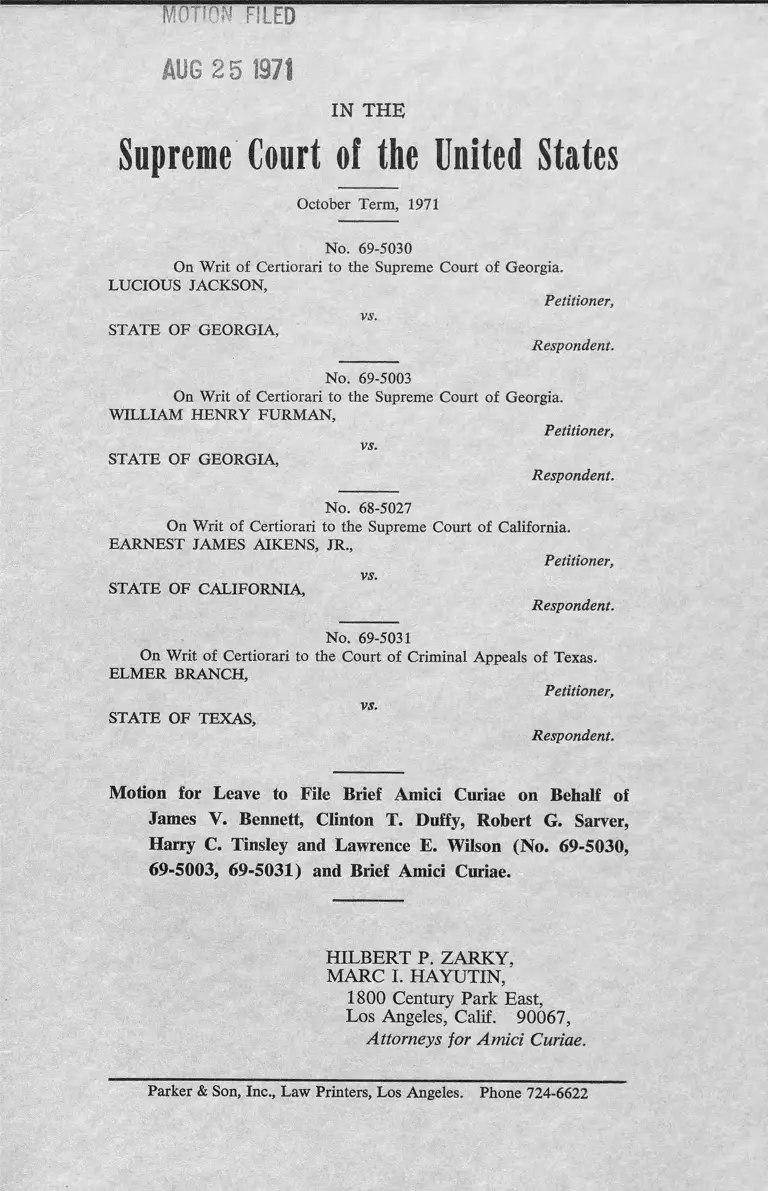

MOTION FILED

AUG 25 1971

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1971

No. 69-5030

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia.

LUCIOUS JACKSON,

Petitioner,

vs.

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Respondent.

No. 69-5003

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia.

WILLIAM HENRY FURMAN,

Petitioner,

vs.

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Respondent.

No. 68-5027

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of California.

EARNEST JAMES AIKENS, JR.,

Petitioner,

vs.

STATE OF CALIFORNIA,

Respondent.

No. 69-5031

On Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Criminal Appeals of Texas.

ELMER BRANCH,

Petitioner,

vs.

STATE OF TEXAS,

Respondent.

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae on Behalf of

James V. Bennett, Clinton T. Duffy, Robert G. Sarver,

Harry C. Tinsley and Lawrence E. Wilson (No. 69-5030,

69-5003, 69-5031) and Brief Amici Curiae.

HILBERT P. ZARKY,

MARC I. HAYUTIN,

1800 Century Park East,

Los Angeles, Calif. 90067,

Attorneys for Amici Curiae.

Parker & Son, Inc., Law Printers, Los Angeles. Phone 724-6622

SUBJECT INDEX

Page

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae on

Behalf of James V. Bennett, Clinton T. Duffy,

Robert G. Sarver, Harry C. Tinsley and Law

rence E. Wilson (No. 69-5030, 69-5003, 69-

5031 ....... .................... ......... ................................ i

Brief Amici Curiae on Behalf of James V. Bennett,

Clinton T. Duffy, Robert G. Sarver, Harry C.

Tinsley and Lawrence E. Wilson ..... .............. 5

Opinions Below ........... ........................ ............ ....... 5

Jurisdiction ...... ................................. .......... .......... 6

Interest of Amici Curiae ......................................... 6

Argument .............................. ................. ................... 7

The Infliction of the Death Penalty in Each of

the Pending Cases Would Constitute Cruel

and Unusual Punishment in Violation of the

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments ............ 7

A. The Death Penalty Is Arbitrarily and Ca

priciously Imposed ............................. . 7

B. The Death Penalty Does Not Deter ..... 8

C. The Death Penalty Is a Tremendous

Human Waste ..... ................ ......... ....... . 10

D. The Imposition of the Death Penalty Ad

mits of No Errors ..... .......... .................. 11

E. The Death Penalty Hampers Effective Ad

ministration of Our Prison System ___ 11

F. The Death Penalty Is Barbaric ............ 12

Conclusion ..................................... ........ .......... ...... 14

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases Page

Aikens v. California, No. 68-5027, 70 Cal. 2d

369 ................. .....................................................1, 6

Branch v. Texas, No. 69-5031, 447 S.W.2d 932..2, 6

Furman v. Georgia, No. 69-5003, 225 Ga. 253 .2 , 6

Jackson v. Georgia, No. 69-5030 225 Ga. 790 .. 6

Statute

United States Code, Title 28, Sec. 1257(3) .......... 6

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1971

No. 69-5030

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia.

LUCIOUS JACKSON,

vs.

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

No. 69-5003

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia.

WILLIAM HENRY FURMAN,

Petitioner,

vs.

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Respondent.

No. 69-5031

On Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Criminal Appeals of Texas.

ELMER BRANCH,

Petitioner,

vs.

STATE OF TEXAS,

Respondent.

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae on Behalf of

James V. Bennett, Clinton T. Duffy, Robert G. Sarver,

Harry C. Tinsley and Lawrence E. Wilson (No. 69-5030,

69-5003, 69-5031).

James V. Bennett, Clinton T. Duffy, Robert G.

Sarver, Harry C. Tinsley and Lawrence E. Wilson re

spectfully move for leave to file a brief amici curiae in

these cases. The attorneys for each of the petitioners in

these cases have consented to the filing of this brief. The

Attorney General of the State of California has con

sented to the filing of this brief in Aikens v. California,

No. 68-5027. The Assistant Attorney General of Texas

has stated that it is not the policy of the Attorney

•2—

General’s Office of Texas to consent to the filing of

amicus briefs and has, consequently, failed to give the

requested for consent in Branch v. Texas, No. 69-5031.

The Assistant Attorney General of the State of Georgia,

while stating that that office has no objection to our fil

ing of an amicus brief, has not granted any express

consent in the cases of Jackson v. Georgia, No. 69-

5030, and Furman v. Georgia, No. 69-5003.

In view of the overwhelming importance of the ques

tion which this Court will be required to pass on,

amici curiae believe that this Court should have be

fore it the expression of their views since each has had

intensive personal experience, in an official capacity,

with respect to operation of our penal system and the

infliction of the death penalty.

James V. Bennett is an attorney. He was formerly

Director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons, and pres

ently serves as a consultant to the Bureau. He is a

past Chairman of the Criminal Law Section of the

American Bar Association.

Clinton T. Duffy is a former Warden of San Quen

tin Prison, and also a former member of the California

Adult Authority, and is a member of the Wardens As

sociation of America.

Robert G. Sarver is an attorney. He has served as

Commissioner of Corrections for the States of West

Virginia and Arkansas.

Harry C. Tinsley served as Commissioner of Cor

rections for the State of Colorado until May, 1971. He

is a former Warden of Colorado State Prison, and is a

member of the Wardens Association of America and of

the American Correctional Association. He has served

as president of both organizations.

— 3—

Lawrence E. Wilson is a former Warden of San

Quentin Prison.

Amici have written numerous books and articles on

criminal law and corrections, and on capital punish

ment in particular, have testified before legislative com

mittees concerned with the death penalty, and have

spoken extensively on the subject. Amici have wit

nessed hundreds of executions in the United States.

Through years of first hand experience with the death

penalty, its applications, its victims and its impact on

the administration of justice and the correctional sys

tems in our society, they have become confirmed op

ponents of capital punishment. (In this regard it should

be noted that amici differ in the extent of their oppo

sition to the death penalty in that Mr. Bennett might

permit retention of capital punishment for the most

heinous crimes, which he has suggested might include

assassination of the President, treason and mass murder,

such as by bombing an airplane.) Amici Duffy, Sarver,

Tinsley and Wilson would abolish the death penalty

entirely. Amici are nevertheless of one mind as to the

abolition of the death penalty in almost all cases, in

cluding those now before the Court.

We believe that the proposed accompanying brief

will be of assistance to the Court, and for the reasons

stated above, we respectfully request leave to file the

annexed brief amici curiae.

Respectfully submitted,

Hilbert P. Zarky,

Marc I. Hayutin,

A ttorneys for Movants.

—5—

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1971

No. 69-5030

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia.

LUCIOUS JACKSON,

Petitioner,

vs.

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Respondent.

No. 69-5003

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia.

WILLIAM HENRY FURMAN,

Petitioner,

vs.

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Respondent.

No. 68-5027

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of California.

EARNEST JAMES AIKENS, JR.,

Petitioner,

vs.

STATE OF CALIFORNIA,

Respondent.

No. 69-5031

On Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Criminal Appeals of Texas.

ELMER BRANCH,

Petitioner,

vs.

STATE OF TEXAS,

Respondent.

Brief Amid Curiae on Behalf of James V. Bennett, Clinton T.

Duffy, Robert G. Sarver, Harry C. Tinsley and Lawrence E.

Wilson.

Opinions Below.

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia (Jack-

son v. Georgia, No. 69-5030) holding that the imposi

tion of the death penalty was not in violation of the

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments of the Constitu-

— 6—

tion of the United States prohibiting cruel and unusual

punishment is reported at 225 Ga. 790.

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia (Fur

man v. Georgia, No. 69-5003) holding that the im

position of the death penalty was not in violation of

the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments of the Constitu

tion of the United States prohibiting cruel and un

usual punishment is reported at 225 Ga. 253.

The opinion of the Supreme Court of California

(Aikens v. California, No. 68-5027) holding that the

imposition of the death penalty was not in violation of

the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments of the Consti

tution of the United States prohibiting cruel and un

usual punishment is reported at 70 Cal. 2d 369.

The opinion of the Court of Criminal Appeals of

Texas (Branch v. Texas, No. 69-5031) holding that

the imposition of the death penalty was not in viola

tion of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments of the

Constitution of the United States prohibiting cruel and

unusual punishment is not yet officially reported. Its

opinion is reported in 447 S.W.2d 932.

Jurisdiction.

Petitions for writs of certiorari in each of the cases

were granted on June 28, 1971, limited in each case

to the following question, “Does the imposition and

carrying out of the death penalty in these cases con

stitute cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments?” Jurisdiction of

this Court in all cases is founded on 28 U.S.C. 1257(3).

Interest of Amici Curiae.

The interest of amici curiae has been set forth in

the accompanying motion to file this brief and need

not be reiterated here.

ARGUMENT.

The Infliction of the Death Penalty in Each of the

Pending Cases Would Constitute Cruel and Un

usual Punishment in Violation of the Eighth and

Fourteenth Amendments.

From their personal experiences in the prison sys

tem, amici have concluded that the infliction of the

death penalty does not serve any proven, legitimate

purpose which society may have in imposing punish

ment for the commission of most capital offenses. While

amicus James V. Bennett, as noted in the accompany

ing motion, believes that capital punishment may be

appropriate in certain unusual situations, all amici

are firmly convinced that in cases involving rape or

murder, such as are involved here, the death penalty

cannot be justified as legitimate punishment.

A. The Death Penalty Is Arbitrarily and Capriciously Imposed.

Amici have dealth with thousands of men and some

women condemned to death and with thousands of

other men and women convicted of similar crimes (in

many instances convicted of more heinous crimes than

those who have been condemned to die for their acts)

but who have received jail sentences. Of course, the

facts in each case are different. Nevertheless, any ward

en of a large prison, and certainly amici collectively,

have vastly more experience with persons convicted

of capital offenses than any jury, prosecutor or trial

judge. Amici respectfully submit that they are there

fore capable of generalizing about the crimes commit

ted by these thousands of persons. What is it that dis-

tinguishes those who have been condemned to die from

those who are permitted to live? What is it that dis-

aw I -IIIin n "" mMi— —— f r —ffffi te m s s a s s ® 331

tinguishes a man who, after having exhausted all ap-

— '7—

— 8—

peals must die at the_hands of the State, from the

man who is given a chance to demonstrate his re

habilitation after serving what is generally a 13 to

16 year term of imprisonment, and who may there

after become a constructive member of society ( though

many lifers die in prison after serving 20, 30, or even

40 years)?

Bluntly, the distinguishing characteristics are pover

ty, ignorance" and~ouToTail statisficabWop^idn" "race.

Tins overwhelming fact is recognized not just by prison

and probation officials and clerics who administer last

rites to the condemned men, but by the prisoners them

selves, whether condemned or not. Whatever may have

gone into a judge’s or jury’s decision to visit death rather

than life upon a convicted man, insofar as the prison

community is concerned, the arbitrariness with which

the death penalty is i ro posed^inak^

supposedly rehabilitative system, and makes incalcula-

bly more difficult the arduous task of rehabilitating

those who have by their crimes demonstrated a lack of

understanding of our concepts of justice and law.

B. The Death Penalty Does Not Deter.

Amici, and Mr. Duffy in particular, have made ex

tensive personal efforts during the tenures of their of

fices as wardens to determine what impact, if any,

the death penalty has had on convicted criminals.

Warden Duffy has interviewed hundreds of convicted

men and women, both those who have been condemned

to die and those who have been allowed to live. He

has discussed the issue with prisoners who might have

been condemned to death by the nature of their crimes,

and prisoners whose crimes did not admit of the death

penalty. As Warden Duffy testified in 1968 in an ap-

— 9

pearance before the sub-committee of the State Judi

ciary Committee, the invariable answer to his questions,

given when the prisoner has already been convicted

and need not curry favor with jailer or prosecutor, is

that the existence of the ̂ de^ r ’̂ m yfTW t^ 11te.lv

no impact on the perpetrators of the various crimes,

whether the crime involved was burglary, robbery, rape,

kidnapping or premeditated murder. Rather, invariably,

the criminal has acted either out of passion or with tKe

unalterable belief that he will not be caught.

Amici wish to go on record as emphatically disavow

ing any argument that the existence of the death penal

ty protects the administration of our prison system.

In their opinion, any such argument is wholly falla

cious, and the only impact of the death penalty in the

prison community, except for those who are executed, is

a terribly deleterious impact on prison morale—on

both sides of the cell. On the contrary, amici are per

sonally aware of instances of homicides within prison

walls and even homicides by persons who have been

involved in an official capacity with the administra- f

tion of the death penalty, including in the case of

Warden Duffy, a deputy sheriff who used to bring pris-

oners to San Quentin regularly and another man who j

helped install a lethal gas chamber at San Quentin and

later killed three people. He was sentenced to death l

and died in San Quentin’s gas chamber. Interviews

with such persons again produced the invariable re

sponse that the death penalty was the farthest thing

from their minds when they committed their crimes.

Amici think it ironic indeed that the only argument

in favor of the death penalty which has some claim to

legitimacy, that of deterrence, is mocked by the very

method of death. If it be thought that the spectacle de-

10—

scribed below would have a deterrent impact at least

on those who must witness the awful sight, then why

are executions conducted with only a very few wit

nesses present and the procedures kept as secret as

possible? This is a far cry from public executions in

17th and 18th century England. The reasons for

secrecy, amici submit, are clear. As is well known,

homicides- and.other serious crimes increased after,.pub

lic executions in England, and amici believe that even

secreT executions in the United States promote more

serious crimes in the community, rather than deter

them. In addition, those who have imposed this secre

cy ha’ve done so not out of regard for the man who

must die, but in recognition that an execution is a de

moralizing spectacle that degrades any person who par

ticipates in it. Amici believe that if executions were held

in public in America today, the public would insist ̂

onabolition of the death penalty.

C. The Death Penalty Is a Tremendous Human Waste.

On the basis of their long years of professional ex

perience, amici believe that most prisoners can be

changed for the better, whatever the faults of our ex

isting prison system. It is also statistically verifiable

and comports with the personal experience of amici

that persons convicted of capital offenses who are not

executed, generally make very good prisoners. Not all

of them are on parole. Warden Duffy alone saw 80

men die of natural death in prison, some of whom had

served sentences of 30 to 40 years in the ten year pe

riod which he surveyed with complete statistics. How

ever, those who are paroled are, in the opinion of al

most all persons in any way involved in the adminis

tration of our parole system, by far the best parolees.

l i

lt is an extreme rarity that a man who has been con

victed of a capital offense and paroled is- ever con

victed of another serious offense and returned to pris

on. To deny a chance at parole, especially in the ar

bitrary and capricious manner in which the denial is

now made is to sacrifice society’s legitimate interest in

rehabilitation in favor of the base desires of some for

retribution and vengeance.

D. Tjlie Imposition of the Death P̂enalty Admits of No Error!s.

There have been errors. Whatever the procedural

safeguards which may be imposed by this Court and

by various legislatures, no system can be wholly free

from error and an innocent person once put to death

cannot be returned to life. More frequently there are

the last minute commutation or pardons. Amicus Ben

nett has written graphically of his own experience in

volving emergency telephone calls that cannot be com

pleted and break-neck automobile rides in an attempt

to convey a message of presidential pardon before the

executioner administered the final penalty.

E. The Death Penalty Hampers Effective Administration of

Our Prison System.

Amici respectfully submit that the existence of capi

tal punishment dehumanizes our system of prison ad

ministration to such a degree that it is increasingly dif

ficult to obtain humane and enlightened administra

tors. Amici have personally known of numerous in

stances of persons who are unwilling to become involved

in administering the death penalty who are very com

petent administrators and who are very concerned with

the administration of our prison system. Amici have

also known of instances of competent administrators

resigning after the occurrence of a particularly grue

— 12—

some experience, ana amicus Sarver stated publicly dur

ing his tenure in office that he would not permit an

execution to take place so long as he was in charge of

the correctional system.

F. The Death Penalty Is Barbaric.

Since very few persons have witnessed an execution,

very few can realize the details, which we can only de

scribe as barbaric, which are involved in the prepara

tion fbr,..antt''‘'1hti....,c;arrying out of the death penalty.

A bi^ef description pf the methods of legalizing killing

now empTOyw! ■ny*■?MiULiy juiisdictions in the United

States seems appropriate.

1

The day before being executed, the prisoner con

demned to death by hanging goes through the harrow

ing experience of being weighed and measured for neck

size and length of drop, to assure that his neck will

break when he is hanged. The hanging itself, whether

the prisoner is dropped through a trap, after climbing

the traditional 13 steps, or whether he is jerked from

the floor after having been strapped, blackcapped and

noosed, is a very gruesome spectacle. Generally, three

men in a small enclosure on the gallows cut taut strings;

one of these springs the trap, while the other two are

attached to dummy ropes. This somewhat bizarre pro

cedure is designed to give the three officers some feel

ing of non-responsibility for the death of their vic

tim. The prison guard stands at the feet of the hanged

person and holds his body steady, because during the

first few minutes there is usually considerable strug

gling by the condemned man as he tries to breathe.

Sometimes his neck does not break and he strangles

to death. His eyes pop almost out of his head, his

tongue swells and protrudes from his mouth, his neck

— 13—

may be broken and theTTOpelnay rip large portions of

his skin and flesh from the side of his face on which

the noose is set. He urinates, he defecates, and his

droppings fall to the floor while witnesses look on.

In almost all executions at least one witness faints or

has to be helped out of the witness room. The prisoner

remains dangling from the end of the rope from 8 to

14 minutes before the attending doctor climbs up a

small ladder and listens to his heartbeat with a stetho

scope and pronounces him dead.

In States which practice electrocution, the body of

the condemned man is prepared beforehand with a fas

tening, and one of his pants legs is split in order that

an electric plate can be placed against his leg. When

the executioner throws the switch that propels the elec

tric current through the body of the prisoner, the vic

tim cringes from torture, his flesh swells and his skin

stretches to a point of breaking. He defecates, he urin

ates, his tongue swells and his eyes pop out. In some

cases his eyeballs rest on his cheeks; his flesh is burned

and smells of cooked meat; sometimes a spiral of smoke

rises from his head.

When a firing squad is the method of death, several

rifle shots are fired, all but one of which is effective.

As in the case of hanging and electrocution, shooting

disfigures the body of the prisoner.

In administering death by lethal gas, the State keeps

the prisoner in a holding cell in a separate room for

his last few days, usually not more than 20 feet from

the lethal gas chamber. He is dressed in blue jeans

and a white shirt as other garments might hold a pocket

of gas. He is accompanied 10 or 12 steps to the gas

chamber by two officers, quickly strapped in a metal

14-

chair, a stethoscope applied and the door sealed. Out

of sight of the witnesses the executioner, on a signal

from the warden, presses the lever which allows the

cyanide gas eggs to mix with the distilled water and

sulphuric acid. At first there is extreme evidence of

horror, pain and strangling. The prisoner’s eyes pop,

they turn purple, they drool. Soon the prisoner is un

conscious. It is a horrible sight, at which witnesses fre

quently faint.

Whatever the means of death, the execution of a hu

man being is a degrading spectacle which few can

stomach. It is carried out in secret. The victim has

paid his “debt to ..society”.-, by.-.suffering the ultimate ^

punishment; but the State is not the richer.

Conclusion.

The death penalty itself is cruel and barbarous, im

posed on the uneducated, the poor and the black and

brown. Its existence distorts our whole system of crim

inal justice, brings distrust upon our courts, creates

suspicion of the adversary system and makes the ad

ministration of our correctional system shunned by

constructive and humane individuals who will not be in

volved in executing a death sentence. Almost all of

western society save the United States has abolished

the death penalty and the trend has become world

wide, except for such politically torn countries as Iraq

and some of the African nations. Amici respectfully

submit that the death penalty has no place in the ad

ministration of justice in the United States.

15—

For each of the reasons discussed above, the death

sentence imposed upon petitioners in the cases before

the Court should be invalidated.

Respectfully submitted,

H ilbert P. Zarky,

Marc I. Hayutin,

Attorneys for Amici Curiae.

Service of the within and receipt of

thereof is hereby admitted this...............

of August, A.D. 1971.

a copy

......day