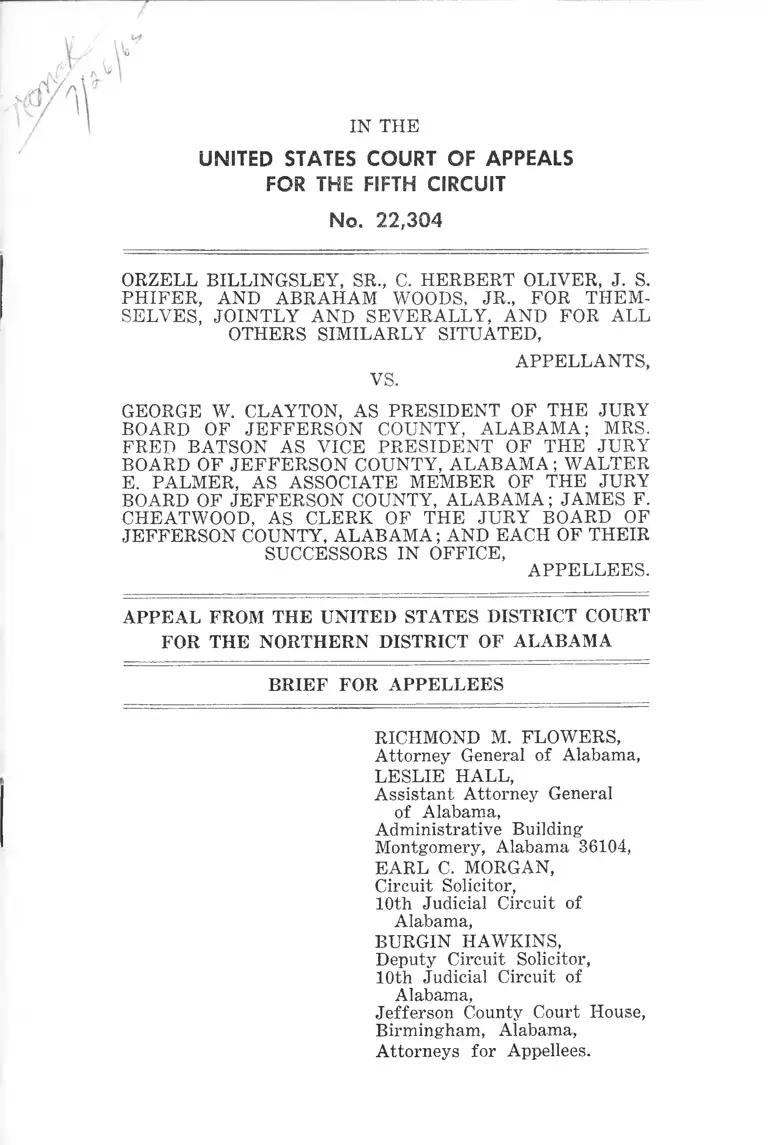

Billingsley v. Clayton Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

July 23, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Billingsley v. Clayton Brief for Appellees, 1965. 07efbfde-c69a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3e3edf7f-c027-4d2a-91ed-b8b2210479f8/billingsley-v-clayton-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALSFOR THE FIFTH CIRCUITNo. 22,304

ORZELL B ILLIN G SLE Y , SR., C. HERBERT OLIVER, J . S. P H IFE R , AND ABRAH AM WOODS, JR ., FOR TH EM SE L V E S, JO IN T L Y AND SE V E R A L L Y , AND FOR A L L OTHERS SIM ILAR LY SITUATED,A PPELLAN TS,VS.GEORGE W. CLAYTON, AS PRESIDENT OF THE JU R Y BOARD OF JE F F E R S O N COUNTY, A L A B A M A ; MRS. FRED BATSON AS V IC E PR ESID EN T OF THE JU R Y BOARD OF JE F F E R S O N COUNTY, A L A B A M A ; W ALTER E. PALM ER, A S ASSOCIATE MEMBER OF THE JU R Y BOARD OF JE F F E R SO N COUNTY, A L A B A M A ; JA M E S F. CHEATW OOD, AS C L E R K OF TH E JU R Y BOARD OF JE F F E R SO N COUNTY, ALAB A M A ; AND EACH OF THEIR SUCCESSORS IN OFFICE, A P P E L L E E S.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEESRICHMOND M. FLOW ERS, Attorney General of Alabama, L E SLIE H A LL,Assistant Attorney General of Alabama,Administrative Building' Montgomery, Alabama 36104, E A R L C. MORGAN,Circuit Solicitor,10th Judicial Circuit of Alabama,BURGIN HAW KINS,Deputy Circuit Solicitor,10th Judicial Circuit of Alabama,Jefferson County Court House, Birmingham, Alabama, Attorneys for Appellees.

IN D EX

Page

STATEM ENT. ..:...................... ........................................................................ 2

A RG U M EN T..................1................................................................................. 17

A P P E N D IX A .............................................................. .................................. 21

l

TABLE OF CASES

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282, 94 L. Ed. 839,70 S. Ct. 629 ...................................................................................... 18

Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565, 40 L. Ed. 1075,16 S. Ct. 904 ...................................................................................... 18

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U. S. 202, 13 L. Ed. 2d 759,85 S. Ct. 824, 33 L. W. 4231 ..............................................18, 20

Thomas v. Texas, 212 U. S. 278, 282, 53 L. Ed. 512,513, 29 S. Ct. 393 .............................................................................18

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313, 322-323,25 L. Ed. 667, 670-671 ...................................................................18

STATU TES:Title 28, U. S. C. A ., Section 2281 .............................................. 2Title 28, U. S. C. A ., Section 1343(3) ........................................... 3Title 42, U. S. C. A ., Sections 1981 and 1983 ................................ 3Title 28, U. S. C. A ., Section 2201 .............. ................................... 3Title 30, Sections 1-100, Code of Alabama 1940(Recompiled 1958) ....................................... 3Title 62, Sections 196-228, Code of Alabama 1940(Recompiled 1958) ........................................................................... 4Title 62, Section 199, Code of Alabama 1940(Recompiled 1958) ........................................................................... 4Title 30, Section 21, Code of Alabama 1940(Recompiled 1958) .......................................................................4, 6Title 62, Section 200, Code of Alabama 1940(Recompiled 1958) .......................................................................... 4ii

Title 30, Section 20, Code of Alabama 1940(Recompiled 1958) .................. .................................................. 4Title 30, Section 3, Code of Alabama 1940(Recompiled 1958) ...................................................................5, 21Title 35, Section 11, Code of Alabama 1940(Recompiled 1958) ...................................................................5, 21Title 62, Section 201, Code of Alabama 1940(Recompiled 1958) ........................................................................... 5

CON STITU TION AL P R O V ISIO N S:Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the UnitedStates Constitution .......................................................................... 3

R U L E S :Rule 23(a) (3), F . R. C. P .................................................................... 3

OTHER A U T H O R IT IE S:1960 United States Census, Alabama, Table 7,pages 2-13 ............................................................................................... 5H. L. Mencken, The American Language, page 129.................20

iii

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 22,304

ORZELL B IL L IN G SL E Y , SR., C. H ERB ERT O LIVER, J . S. PH IFE R , AND ABRAH AM WOODS, JR ., FOR TH EM SE L V E S, JO IN T L Y AND S E V E R A L L Y , AND FOR A L L OTHERS SIM ILA R Y SITU ATED ,A PPE LLA N T S,V S.GEORGE W. CLAYTO N , AS PR ESID EN T OF TH E JU R Y BOARD OF JE F F E R S O N COUN TY, A LA B A M A ; MRS. FR ED BATSON, AS V IC E PR ESID EN T OF TH E JU R Y BOARD OF JE F F E R S O N COUNTY, A L A B A M A ; W ALTERE. PALM ER, AS A SSO CIAT E M EM BER OF TH E JU R Y BOARD OF JE F F E R S O N COUNTY, A L A B A M A ; JA M E SF. CHEATW OOD, AS CLE R K OF TH E JU R Y BOARD OF JE F F E R S O N COUNTY, A L A B A M A ; AND E A C H OFTH EIR SUCCESSORS IN O FFICE ,A P P E L L E E S.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

STATEMENT

Four Negro Plaintiffs filed a complaint in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama, “ for themselves, jointly and severally, and for all others similarly situated,” against the three Members and the Clerk of the Jury Board of Jefferson County, Alabama, “and each of their successors in office,” seeking a temporary restraining order, or, in the alternative, a preliminary injunction to be later made permanent, or, in the alternative, a special three-judge court to hear the cause and declare the rights of the Plaintiffs and others similarly situated pursuant to Title 28, U. S. C. A ., Section 2281. The Plaintiff, C. Herbert Oliver, is a resident of that part of the county known as the “ Bessemer Cut-Off” (R. 22). The other Plaintiffs reside in the Birmingham Division of the county (R. 22). The Plaintiff, Billingsley, had a civil action pending in the Circuit Court of Jefferson County, which was to be tried when reached in proper order (R. 23).The Plaintiffs prayed that the Court enter a Judgment or Decree declaring that “the policy, custom, or usage of the Defendant Board in refusing to place all qualified Negroes on the jury rolls and in the jury boxes, solely on account of race or color, is unconstitutional and in violation of the Fourteenth and Fifth Amendments to the United States Constitution” (R. 11) ; and enjoining and restraining the Defendant Board Members, their agents, employees, successors, “ and persons in active concert and participation with them” from “ failing or refusing to place the names of all qualified persons on the jury rolls and in the jury boxes solely on account of their race or color” (R. 11), and from “ utilizing any names presently contained in the jury boxes or on the jury rolls in Jefferson County, Alabama, for jury duty in any court in such county until such time as the names of all Negroes qualified for jury duty therein shall

2

have been placed in such jury boxes or on such jury rolls”(R. 11-12).The Plaintiffs based their claims to the relief prayed for on allegations that the method of selection of the names of Negroes to be placed on the jury rolls and in the jury boxes of Jefferson County, Alabama, by the Defendant Board Members “ is highly illegal and arbitrary and contrary to the method prescribed by the Constitution and laws of the State of Alabama and of the United States of America” (R. 8), thereby depriving them, and others similarly situated, of rights guaranteed them by the Constitution and laws of the State of Alabama and by the Constitution of the United States; that there exists a system or practice in the drawing or organization of juries to serve in the county deliberately designed to discriminate against Negroes [This is not at

tributed to the Members of the Ju ry Board or to its Clerk3; and that one of the Plaintiffs (Billingsley) then had a Civil Jury Case pending on the Docket in the Circuit Court of the county (R 8-9).The Plaintiffs sought to invoke the jurisdiction of the Court under the provisions of Title 28, U. S. C. A ., Section 1343(3), Title 42, U. S. C. A ., Sections 1981 and 1983, the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, Title 28, U. S. C. A ., Section 2201, and Rule 23(a) (3), F . R. C. P. (R. 3).The Defendants filed a Motion to Dismiss the Complaint and the Motion for Preliminary Injunction in which they questioned the statement of a cause of action and the jurisdiction of the Court, as well as the power of the Court to award the relief sought (R. 17-21).The general provisions, with respect to juries and the jury commissions of the several counties of the State of Alabama, are found in Title 30, Sections 1-100, Code of3

Alabama 1940 (Recompiled 1958). Except for certain general provisions, the matter is largely regulated in Jefferson County by Title 62, Sections 196-228, Code of Alabama 1940 (Recompiled 1958). In Jefferson County, the body charged with the selection of jurors is called a “ Jury Board” whereas, in other counties it is called a “ Jury Commission.” In Je fferson County the law requires (Section 199) the Board to obtain the names of male citizens between the ages of 21 and 65.1 In other areas of the State, a person over 65 is not required to serve on a jury (Title 30, Section 21), but is not mandatorily excluded.2 Under Section 200 of Title 62, the Jury Board is deemed to have performed the duties required of it by law when it shall have prepared a jury roll otherwise in compliance with law consisting of at least six percent of the population of the county in accordance with the last Federal Census.3 The Complaint and Motion for Preliminary Injunction do not allege that this has not been done.The Complaint merely alleges that the jury rolls of the county contain “ less than five percent of the names of the total number of Negro males eligible for jury duty in said county.”When the roll is made up and the box is filled, the box is then delivered into the custody of the Presiding Judge of the Circuit Court. Under the general provisions of the law, the box is kept in the office of the Probate Judge and the President of the Jury Commission keeps one of the keys to the same (Title 30, Section 20) (R. 28). In Jefferson County the jury box is filled every two years, and the obtaining of information and the selection of jurors for the rolls is a continuous process, with a continuous purging of

1 See Appellants’ Brief, page 80.2 See Appellants’ Brief, page 72.3 See Appellants’ Brief, page 80:. 4

the same. Approximately thirty-five categories of individuals are exempt from jury duty, based upon the nature of the employment of the individuals involved (Title 30, Section 3, and Title 35, Section 11).1 The qualifications of jurors are prescribed by Title 30, Section 21 (R. 28).None of the Plaintiffs alleged that he, himself, possessed the qualifications of a juror or that his name had not been placed on the jury roll or in the jury box. In fact, the evidence showed that all four are ministers, who, in practice, would normally be excused, and one is a teacher, subject to exemption from jury duty under Title 30, Section 3! Only one, Billingsley, alleged that he had any direct interest in the composition of the jury roll and jury box, and that was in connection with a suit pending in the State Circuit Court.By virtue of Title 62, Section 201, the Jury Board is charged with requiring the Clerk of the Board “to scan the registration lists, the lists returned to the tax assessor, any city directory, telephone directory, and any and every other source of information from which he may obtain information, and to visit every precinct at least once a year . . . .” (R. 80-81).The 1960 Census reveals that there were 634,864 people in the county.3 The jury rolls contained the names of 52,729 males, 43,837 being in the Birmingham Division, and 8,892 in the Bessemer Cut-Off (Appellants’ Brief, Appendix A, Page 64). Six percent of the total population of the County is 38,092. Thus, the jury roll contains 14,637 in excess of six percent of the total population.There was no testimony or evidence as to the percentage

1 Appendix A hereto.3 1960 United States Census, Alabama, Table 7, pages 2-13.5

of each race between the ages of 21 and 65 eligible for jury service. Furthermore, there was no testimony or evidence as to the percentage of each race claiming exemptions (Appellants’ Brief, Appendix A , Page 68).Since the Appellants have deliberately slanted their Brief to indicate that the testimony and evidence are in their favor, the Appellees deem it advisable to call to the attention of the Court certain facts as demonstrated by the Record.

On Pages 3, 15, 16 and 32 of their Brief the Appellants seem to assume that as a prerequisite to being a juror in Alabama, one must be a registered voter. This is not a fact. Title 30, Section 21, Code of Alabama 1940 (Recompiled 1958) makes eligible for jury service “male citizens of the county who are generally reputed to be honest and intelligent men and are esteemed in the community for their integrity,good character and sound judgm ent;.............” There is norequirement that a juror must be a registered voter in Alabama. (See R. 91.)The Plaintiffs called as their own witness one H . P.

Lipscomb, J r ., an attorney, of Bessemer, Alabama, whose testimony at best indicated that in his some 42 years of law practice he had obsverved very few Negroes on jury panels in Bessemer. He gave no testimony as to jury panels in the Birmingham Division. Likewise, he gave no testimony as to the operations of the Jury Board or its Clerk, the Appellees herein (R. 66-73).

M r. Jerry 0 . Lor ant, an attorney, whose practice was chiefly confined to Birmingham proper was called as a witness by the Plaintiffs, and testified that he had tried many jury cases and had observed many jury cases in which Negroes actually served on the petit juries, and knew of no agreement among attorneys to strike Negroes from the

6

panel or venire (R. 74-81). He further testified that in his observation there was “ not any absence of colored folks on the jury” (R. 76). The attention of the Court is respectfully invited to the fact that this witness completely refuted the allegations of the Complaint (R. 78). This was Appellants’ own witness, and not treated as an adverse witness.

Next, the Appellants called one of the Defendants, namely, Mr. James F . Cheatwood, Clerk of the Jury Board. It should be noted that Mr. Cheatwood was not treated as an adverse witness, as was Mr. George W. Clayton (R. 42, 81-94). Mr. Cheatwood had worked for the Jury Board 14 years, the last four of which were as Clerk (R. 82). He testified that his duties required him to visit every Precinct in the County, which he did (R. 82) ; that he was able to get more information from those persons residing in the higher economic sections (R. 84), and that they were not as evasive as others (R. 84) ; that he had no idea of the racial percentage of the areas surveyed (R. 85) ; that the same procedures were followed in Negro neighborhoods as in White neighborhoods in making surveys for the Jury Board (R. 89) ; that the City Directory was used only as a check on spellings and other possible questions (R. 92) ; that the principal method of survey was house-to-house (R. 92), supplemented by visiting store owners and postmasters in outlying areas (R. 92-93) and writing letters; that it was sometimes impossible to tell by an address on a list whether a person was Negro or White (R. 93-94) ; and that his surveys were always on an impartial basis (R. 81-94).

Mr. David H . Hood, Jr ., an Attorney at Law of Bessemer, Alabama, was called as a witness by the Plaintiffs, and testified that he had been engaged in the general practice of law since 1948; that he had not observed Negroes on the jury panel in the Bessemer Cut-Off “ to any extent” since that time; that within the last two years he had observed7

“ some” Negroes on the panel in Birmingham and that he had not examined the jury roll (R. 95-108),

Mr. William C. Smithson, an Attorney, called as a witness for the Plaintiffs, testified that he was 74 years of age and had been practicing law for approximately 45 years; that his practice had been limited mostly to equity and probate work in the Bessemer area; that he was fairly active up until 1950, but that due to an arthritic condition, he had only been to the Court House in Bessemer on very few occasions (R. 108-109).

Mr. James G. Adams, J r ., called as a witness for the Plaintiffs, testified that he had been a practicing attorney in Birmingham since 1921; that he was familiar with the jury system in Jefferson County; and that there was no way of telling from the names of persons called on a panel for a particular week the racial identification of such persons (R. 109-120) ; and that he only goes to court when he has business there.

Mr. Hugh Lemon, called as a witness for the Plaintiffs, testified that he was an automobile mechanic; that he was a Negro; that about five years before, he had been summoned to serve as a juror; that there were other Negroes on the panel at the time; that he did not serve on the Grand Jury or Petit Jury at that time; that when the venires were called to appear in a certain courtroom, there was no distinction as to race; and that this was the only time that he had ever been summoned for jury service (R. 120-127).

Mr. Arthur D. Shores, called as a witness for the Plaintiffs, testified that he had been practicing law in Birmingham, Alabama, for 25 years; that he had tried cases before juries during that time; that from time to time he had noticed small numbers of Negroes in the jury room; that on one or two occasions he had noticed Negroes on partial

8

panels; that he had been in court and sat at the counsel table at times when the bailiff would bring in the jury box and had observed the procedures; that he had made no effort to furnish the Jury Board with the names of qualified persons to serve as jurors (R. 131-133) ; that he was a Negro ; and that he could not recall ever receiving a request from the Jury Board for a list of names of qualified persons to be suggested as possible jurors (R. 127-136).

Mr. Louis J . Willie, a witness for the Plaintiffs, testified that he was Secretary-Comptroller of the Booker T. Washington Insurance Company; that he was a citizen of Jefferson County, Alabama, and had been such since 1952; that in 1961 he was subpoenaed to serve as a juror for the Circuit Court of Jefferson County, Alabama; that at the time he appeared, there were ten Negroes present; that he was not called to serve on any jury; and that was his sole and only experience as a potential juror (R. 136-143).

Mr. Matt Murphy, an Attorney at Law, who had been practicing in Jefferson County, Alabama, for fifteen years, called as a witness for the Plaintiffs, testified that he had observed as many as eight or ten Negroes on partial panels of jurors out of a total of 24 to 28 or more; and that he did not know of any arrangement or agreement, written rule or custom, or usage, by which any official connected with the courts might agree to furnish or not to furnish Negro jurors (R. 143-147).

M r. A . G. Gaston, a Negro insurance executive in Je fferson County, called as a witness by the Plaintiffs, testified that he was called as a juror in the State Court one time about six or eight years before; that he reported to the jury room on the fifth floor of the Court House; that he attended on two or three days; that he was never called to serve on a jury; and that he was finally told that he was no longer9

needed. He further testified that he is now 68 years of age (R. 171-177).

Mr. Hugh McEniry, a witness for the Plaintiffs, testified that he was an attorney who had been practicing law in Bessemer since 1910; that prior to three years before his testifying, he had observed as many as three Negroes actually serving on petit juries in the Bessemer Cut-Off section of Jefferson County (R. 177-182).

Mr. Edward H. Saunders, a witness for the Plaintiffs, testified that he had been engaged in the practice of law in Bessemer since 1930, except for a period of a little over four years when he was in the United States Air Force; that his practice had been confined almost exclusively to Bessemer; and that in the last five years he had seen Negroes on jury panels (R. 183-185).

Mr. Emmett Perry, Circuit Solicitor of the Tenth Judicial Circuit of Alabama since 1947, called as a witness for the Plaintiffs, testified that he conducted the proceedings before nearly all of the Grand Juries during that period of time, and that nearly every Grand Jury had one or more Negroes serving thereon (R. 210-218).

Mr. John Lair, an attorney, called as a witness by the Plaintiffs, testified that he had been in the general practice of law in Birmingham since 1952; that he had seen as many as seven Negroes on a jury panel; and that he knew of no custom, arrangement, or agreement for preventing Negro jurors from coming from the jury room to the courtroom (R. 218-221).

Judge Wallace Gibson, a Judge of the Circuit Court for the Tenth Judicial Circuit of Alabama, who presided over one of the two criminal divisions of the circuit, testified that he had been a Circuit Judge since 1957 and prior to10

that had been in the general practice of law in Birmingham; that as Judge, he frequently had occasion to draw and organize juries for the trial of cases in the Circuit Court; that within the past 90 days he had one panel of 24, on which there were 6 Negroes; that although approximately five years before there had been some arrangement for Negroes to be left in the jury room and not brought down on a partial panel, there had been no such arrangement during the past five years (R. 221-226).

Mr. C. J . Green, a Negro, who was called as a witness for the Plaintiffs, testified that he had been called as a juror about three times, and on two occasions requested that he be excused; that on the other occasion, which was more than four or five years before, he stayed for one day and was told he was not needed (R. 226-229).

Judge J . Edgar Bowron, Presiding Judge of the Tenth Judicial Circuit of Alabama, testified that he had been a Circuit Judge since 1935, with the exception of two and one- half years during World War II ; that as such Presiding Judge, he drew the cards containing the names of prospective jurors from the jury box; that when the names are drawn, they are given to the Clerk, who makes up the list and gives it to the Sheriff for service; that a jury room Bailiff is in charge of the jury room where all jurors originally assemble; that there is no way of telling, except by reference to name, address, or occupation, and then only by guesswork, as to whether a prospective juror is white or colored until he shows up on Monday morning of the week for which he is summoned; that the venire is kept secret until that Monday morning; that the list is not made public until Monday morning ; that although there frequently have been occasions when attorneys trying cases would agree among themselves that certain prospective jurors would not be brought down from the jury room, such agreement had no reference to race;11

that Negroes had served infrequently on petit juries in his Court; that many jurors of both races asked to be excused (R. 229-244).

Mr. Frederick L . Ellis, a Negro insurance executive in Birmingham, testified that he had been called as a juror twice, the first time about four years before, when there were 10 other Negroes present in a group of some 35 to 40, and again about two years before, when there were about 15 Negroes present; and that he was not sent down on a trial venire on either occasion (R. 244-254).

Rev. J . S . Phifer, a resident of Jefferson County for eight years, testified that he had been summoned for jury duty once approximately four or five years before; that when he arrived at the jury room., a man told him that if he had anything else to do, he could be excused, that he then left; that he did not know any of the members of his congregation or any of his neighbors or friends who had been called for jury duty (R. 254-261).

Rev. Abraham L . Woods, aged 33, testified that he had never been called for jury duty; that he did not know any of the members of his congregation who had been called for jury duty; that he had never made any inquiry to find out whether his name was on the jury roll (R. 261-267).Similar testimony was given by Rev. Allen Thomas (R. 267-269).

Mr. Henry N . Guinn, 73 years of age, testified that he had been called for jury duty three times, the last time being five or six years before; that he never served on a jury; that there were three or four other Negroes present in the jury room with him; that the last time that he was summoned, he was past 65 years of age (R. 270-274).12

Rev. Claude G. Oliver, who is also a teacher at Miles College, testified that he had never been called as a juror (R. 274-276).

Mr. James F . Cheativood, Clerk of the Jefferson County Jury Board since 1958, was called as a witness by the Plaintiffs, and testified that he was charged with the duty of seeing that a survey is made every two years all over the county in order to fill the jury box properly without regard to race, creed, or color; that the Jury Board is the policy making and reviewing group; that since he had been Clerk of the Board, they had always used a house-to-house survey system to make up the jury list; that the policy has not been changed; that they did not use a voters list, City Directory, or Tax Register, because such lists would not show age, or physical disability, nor would such list show present residence addresses ; that in making the survey, if no one is at home, the person making the survey leaves a card at the house; that the staff places information gathered in the survey on daily work sheets; that such information is then checked to determine whether a person has been convicted of a crime or is otherwise disqualified; that the work sheet does not show who is white or who is colored; that the cards placed in the jury box contain no racial identification; that it takes approximately 13 to 14 months to make a survey; that when the survey is being conducted, he hires nine extra workers to work full time for nine months; that they tried to get a cross-section of the county according to the economic standing of the people; that in some small communities, he would go to the postmaster and request him to furnish the names of qualified male citizens over twenty-one, regardless of race, color, or creed; that he had sent out more than eighty letters to Negro professional people requesting them to furnish names of qualified persons; that he only got nine answers to these letters; that he had more difficulty in making surveys in Negro neighborhoods than in White neighborhoods; that13

frequently the Negroes would either not give information or would not come to the door; that many of them were very evasive and vague; that this was especially true in the low economic class (R. 305-306) ; that he had tried calling on some of the addressees of the letters he had written; that he had no idea of the percentage on the jury roll who might be Negroes; that he could not tell by looking at the jury roll whether a person was a Negro or White except in very isolated areas; that he had caused articles to be published in the newspapers regarding the compilation of the jury roll; that letters had been sent to the attorneys for the Plaintiffs (R. 320-322) (See Defendants’ Exhibits 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 9A, 10, and 10A) ; that in making the survey of homes, if the staff could not interview the person residing there, they would leave a postcard (Defendants’ Exhibit 3) ; that the response in the colored sections was less than 5 %, whereas, the response from white sections was approximately 50 % ; that sometimes he would have to walk as many as five or six blocks in alleys in colored sections to get the names of two or three men; that one of the persons to whom letters had been addressed was the witness, Arthur G. Gaston (R. 335-336, Defendant’s Exhibit 12) ; that a similar letter was sent to the witness, Hood (R. 342) ; that he has had thousands of White men come in the office and inquire about their names being in the box, but only two Negro men (R. 349) ; and that no distinction was made as to race in obtaining the names of prospective jurors to be placed on the jury roll and in the jury box (R. 276-353),The 1960 Census reveals that there are 120,205 white males over twenty-one years of age and 51,961 nonwhite males over twenty-one years of age residing in Jefferson County; that between the ages of twenty-one and sixty-five, there were 106,409 white males and 44,864 nonwhite males. Roughly, the percentage is 71 white and 29 nonwhite. The jury rolls consist of 8,892 names from the Bessemer Cut-Off14

and 43,837 names in the Birmingham Division, or a total of 52,729 names on both rolls.

Following the presentation of the above summarized evidence, the District Court entered an Opinion and Order on June 7, 1962, denying the petition for temporary injunction and continuing the motion to dismiss pending a further hearing on the merits (R. 22-32).

On November 2, 1964, the cause came on for final hearing, at which time it was stipulated that the evidence taken on the hearing for temporary injunction would be considered by the Court without any retaking of the same (R. 354 and 33), and additional evidence was heard.

Mr. H . P . Lipscomb, Jr ., who testified previously, was again called as a witness for the Plaintiffs and testified that he had been engaged in the practice of law in Bessemer since 1920; that although he had never seen a Negro actually serve on a petit jury trying a case, during the last two years there had always been several Negroes on the venire in the Bessemer Cut-Off (R. 355-364).

Mr. Billy Ray Whitley, present Clerk of the Jury Board, was called as a witness by the Plaintiffs and testified that he had been such Clerk since July 17, 1964; that prior to that time he had been employed as a Clerk II in the Jury Board office since 1960; that he helped survey the Negro community and five temporary field agents surveyed integrated communities where colored and white persons were living in the same block; that in sparsely settled communities the Clerk of the Board usually contacted store operators and postmasters to obtain names; that the Board still sent out letters seeking names; that the policy had not changed (R. 367-385).15

Judge Edward L . Ball, one of the two Circuit Judges assigned to the Bessemer Division, was called as a witness for the Plaintiffs, and testified that he had been such Judge for seven years; that prior to that he had been engaged in the practice of law since 1939; that up until 1962 he and Judge Goodwin handled both the Criminal and Civil Dockets, but since that time he had been handling all the Civil Dockets and Judge Goodwin had been handling all the Criminal Dockets; that usually the venires contained from four to eight Negroes, although he had never seen a Negro actually serve on a trial jury; that the Court exercises no control over the strikes taken by counsel; that the Jury Board had nothing to do with the box after it was turned over to the Judges; that he had never excused all the Negroes on a venire but had excused some at their request (R. 388-413).

Mr. Elmore McAdory, Deputy Clerk for the Bessemer Division since 1953, testified that since he had been such Deputy Clerk, Negroes had been summoned for jury duty, but that he could not tell from looking at the names on the cards or on the venire list the race of the persons involved (R. 413-434).

Mr. J . T. Cheatwood, former Clerk of the Board, was again called as a witness for the Plaintiffs and reiterated that the house-to-house survey was the principal method used in obtaining the names of qualified prospective jurors; he testified that he and Mr. Whitley made the surveys in what might be considered “rough neighborhoods” ; that the employees of the Jury Board were taken from the list certified by the County Civil Service Board, and that no names of Negroes had ever been so certified to him for the positions to be filled (R. 435-445).There was no evidence presented with regard to the crime, literacy, or disease ratios between the races, either in the Birmingham Division or the Bessemer Division.16

On December 2, 1964, the District Court made additional Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law and entered a Final Judgment and Decree denying the relief sought (R. 34- 37). It is from this Final Judgment and Decree that the present appeal was taken (R. 37).

ARGUMENTThe Appellants concede that the Jury Board of Jefferson County, Alabama, employs the proper technique of jury selection (See Appellants’ Brief, Pages 22-23), but then proceed with a long and tenuous dissertation on such subjects as the war on poverty, the problems of poverty and race, the weak and oppressed, the wealthy and powerful, “ White Southern justice,” “ the middle class,” lynchings, the “Negro Revolution,” so-called “ nonviolent movements,” demonstrations, marches, class struggles, the laws of probability and other ephemeral theories, attempting to bolster their argument by citations from a defunct magazine (Literary Digest), and a discredited pollster (George Gallup) as well as the citation of a book and articles written by one of the attorneys for Appellants, i. e., Charles Morgan, Jr .Under the laws governing the Jury Board of Jefferson County, Alabama, the Jury Board is deemed to have performed its duties when it shall have prepared a jury roll otherwise in compliance with law consisting of at least 6% of the population of the county in accordance with the last Federal Census. The complaint and the motion for preliminary injunction and permanent injunction do not allege that this has not been done.The complaint merely alleges that the jury rolls of the county contain “less than 5% of the names of the total number of Negro males eligible.. . for jury duty in said county.”17

The statute does not even require the jury roll to contain at least 6% of the eligible male population, regardless of race or color, but only 6% of the total population. Naturally, therefore, the jury roll conceivably contains less than 6% of the eligible White males as well as less than 6% of the eligible Negro males, since the percentage is calculated on the total population, which includes women and children as well as those over 65, those who have been convicted of crimes, and others ineligible to serve.There is nothing in the Constitution and Laws of the State of Alabama or in the Constitution and Laws of the United States which requires that a jury roll and a jury box be compiled in the exact ratio of the eligible White males to the eligible Negro males. Swain v. Alabama, 380 U . S. 202, 13 L. Ed. 2d 759, 85 S. Ct. 824, 33 L. W. 4231; Virginia v.

Rives, 100 U. S. 313, 322-323, 25 L. Ed. 667, 670-671; Gibson

v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565, 40 L. Ed. 1075, 16 S. Ct. 904;

Thomas v. Texas, 212 U. S. 278, 282, 53 L. Ed. 512, 513, 29 S. Ct. 393; Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282, 94 L. Ed. 839, 70 S. Ct. 629.As Mr. Justice White said in Swain v. Alabama, supra, “ Neither the jury roll nor the venire need be a perfect mirror of the community or accurately reflect the proportionate strength of every identifiable group.”The members of the Jury Board denied that racial considerations entered into their selections of either their contacts in the community or the names of prospective jurors. There is no evidence that the members of the Jury Board applied different standards or qualifications to the Negro community than they did to the White community, nor was there any meaningful attempt to demonstrate that the same proportion of Negroes qualified under the standards administered by the Jury Board. It is not clear from the record18

that the members of the Jury Board or their Clerk knew how many Negroes were in the respective areas or on the jury roll. An imperfect system is not equivalent to purposeful discrimination based on race. The burden of proof was not carried by the Appellants in this case. Swain v. Alabama, supra.The Appellants ignore entirely the almost total failure of the Negro leaders in the county to assist the Jury Board in any way in securing the names of qualified Negroes to be placed on the jury roll, yet they attempt to blame the disparity, if any, of racial representation on the White people. They refuse to lay the blame where it rightly belongs—that is, on their own people.As pointed out by Judge Grooms in his Additional Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law on December 2, 1964:“ Once the jury box has been filled, possession is surrendered to the Probate Judge of the County. These Defendants have nothing whatever to do with the summoning of jurors for duty, drawing their names from the box, excusing them from service after they have been summoned, assigning them to numbered juries or selecting those who shall serve on the Grand Jury or on a Trial Jury. The number of peremptory challenges in both civil and criminal cases is fixed by statute. The exercise of such peremptory challenges rests exclusively with the parties.“ Any disparity between Negro and White jurors resulting from the summoning, drawing, excusing, assigning or selecting of jurors cannot be attributed to these Defendants.”In addition to advancing certain socialistic theories in their brief, the Appellants (at Pages 7 and 32) take to task the usage by one of the witnesses of the term “nair.” Al-19

though this term may seem somewhat of a vulgarity to our sophisticated, educated colleagues at the Bar, and it even may seem so to others, it is respectfully pointed out to the Court that this word and variations thereof, such as “ary” and “nary” still survive in this country in certain portions thereof as represented by what is known as the “ Essex dialect.” 1 We can no more stamp it out than we can sin, motherhood, or sex.The Plaintiffs have made certain allegations as to discrimination in compiling the jury rolls and jury boxes in Jefferson County, Alabama. The burden was on the Appellants to prove such allegations. This they have wholly failed to do. Swain v. Alabama, supra.

CONCLUSIONFor the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted that the Orders, Judgments and Decrees of the District Court should be affirmed. Respectfully submitted,RICHMOND M. FLOW ERS, Attorney General of Alabama,L E S L IE H ALL,Assistant Attorney General of Alabama,Administrative Building, Montgomery, Alabama 36104,

1 H . L . Mencken, The American Language, Page 129.

20

E A R L C. MORGAN,Circuit Solicitor,10th Judicial Circuit of Alabama,BU R G IN H AW KINS,Deputy Circuit Solicitor,10th Judicial Circuit of Alabama,Jefferson County Court House, Birmingham, Alabama,Attorneys for Appellees.

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE//'I hereby certify that on the .......... ......... day of July, 1965,I mailed the requisite number of copies of the foregoing brief, United States mail, postage prepaid, to Orzell Billingsley, Jr ., Peter A . Hall, J . Mason Davis, Oscar W. Adams, Jr ., Melvin L. Wulf, Jack Greenberg, Norman Amaker, and Charles Morgan, Jr ., Attorneys for Appellants, at their respective addresses. L E S L IE H ALL,Assistant Attorney General of Alabama,Of Counsel for Appellees

A PPEN D IX “ A ”Title 30, Section 3, Code of Alabama 1940 (Recompiled 1958) : 21

“ The following persons are exempt from jury duty, unless by their own consent: Judges of the several courts; attorneys at law during the time they practice their profession; officers of the United States; officers of the executive department of the state government; sheriffs and their deputies; clerks of the courts and county commissioners; regularly licensed and practicing physicians; dentists; pharmacists; optometrists; teachers while actually engaged in teaching; actuaries while actually engaged in their profession; officers and regularly licensed engineers of any boat plying the waters of this state; passenger bus driver-operators, and driver- operators of motor vehicles hauling freight for hire under the supervision of the Alabama public service commission; railroad engineers, locomotive firemen, conductors, train dispatchers, bus dispatchers, railroad station agents, and telegraph operators, when actually in sole charge of an office; newspaper reporters while engaged in the discharge of their duties as such; regularly licensed embalmers while actually engaged in their profession; radio broadcasting engineers and announcers when engaged in the regular performance of their duties; the superintendents, physicians, and all regular employees of the Bryce hospital in Tuscaloosa county and the Searcy hospital in Mobile county; officers and enlisted men of the national guard and naval militia of Alabama, during their terms of service and convict and prison guards while engaged in the discharge of their duties as such.”Title 35, Section 11, Code of Alabama 1940 (Recompiled 1958) :“ Owing to liability to call for military duty during their term of service, every officer and enlisted man of the national guard and naval militia of Alabama shall be exempt from poll tax, road duty, street tax and jury duty during his active membership, any local or special laws to the contrary notwithstanding; provided that every person who shall have

22

served an aggregate of twenty-one years in the active national guard or naval militia of Alabama shall be thereafter forever exempt from poll tax, road duty, street tax and jury duty by reason of such service, any other laws to the contrary notwithstanding. The commanding officer of any company, troop, battery, or any similar organization, shall furnish each member of his command applying for same such certificate of membership as may be prescribed by the adjutant general, signed by such commanding officer, which certificate shall be accepted by any court as proof of exemption as provided by this law. Such certificates shall be issued to every officer and enlisted man, as aforesaid, under such regulations and upon such forms as may be prescribed and provided by the adjutant general. The said certificates shall be effective, as to poll tax, for the poll tax year for which same is issued without regard to dates prescribed for payment of poll tax, and as to the other exemptions provided herein, the same shall be effective for the calendar year in which it is issued. The commanding officer of a division, brigade, regiment or separate battallion shall issue similar certificates to each of his field officers, commissioned and enlisted staff, and the adjutant general with the approval of the governor shall issue similar certificates to each general officer of the Alabama national guard, and to each regimental commander not in the brigade or division of a general officer of the line of the Alabama national guard, and to each commissioned officer, warrant officer and enlisted man of the national guard whose immediate tactical commanding officer is not a member of the Alabama national guard.”

23