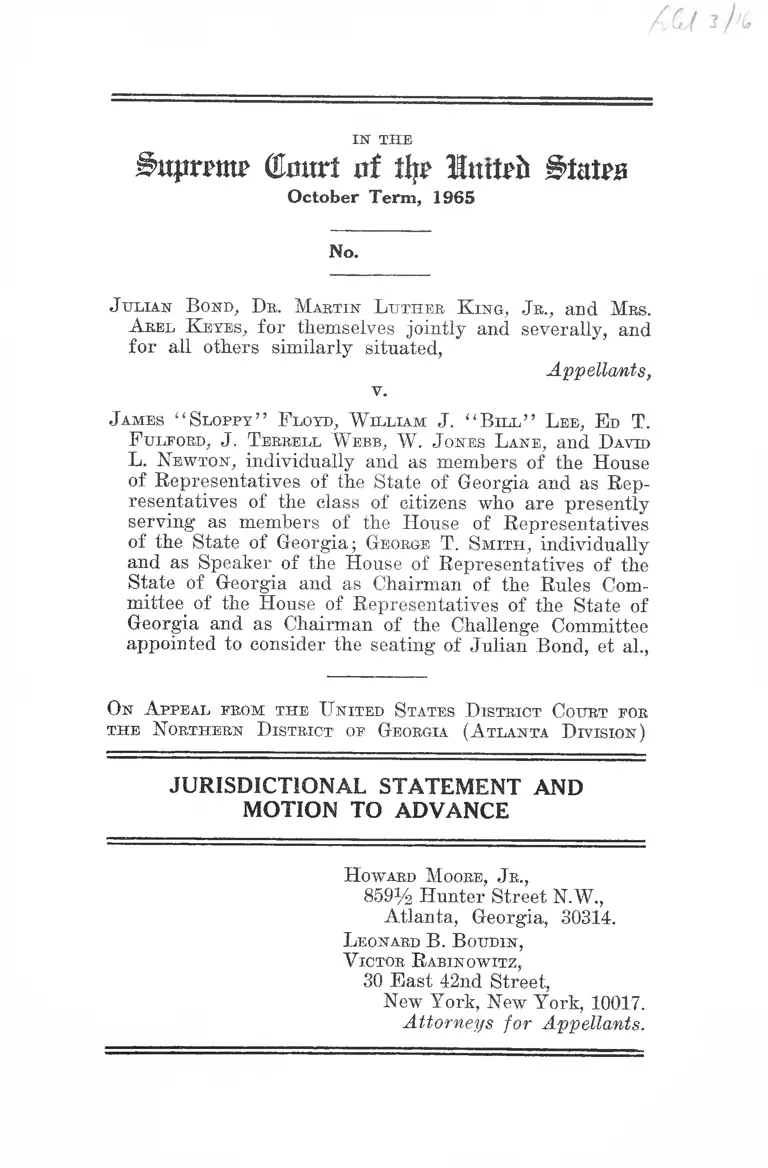

Bond v. Floyd Jurisdictional Statement and Motion to Advance

Public Court Documents

March 16, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bond v. Floyd Jurisdictional Statement and Motion to Advance, 1966. 3ed3b916-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3e4bb072-c1fe-4197-9904-6c9586b92661/bond-v-floyd-jurisdictional-statement-and-motion-to-advance. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

1ST THE

Bupttm ( to r t irt % Inttrb Btntm

O cto b e r T erm , 1965

No.

J ulian B ond, D r . M artin L u t h e r K in g , J r ., and M rs.

A rel K eyes, for themselves jointly and severally, and

for all others similarly situated,

Appellants,

v.

J ames “ S l o ppy ” F loyd, W illiam J . “ B il l ” L ee , E d T .

F uleord, J . T errell W ebb, W . J ones L a ne , and D avid

L . N ew ton , individually and as members of the House

of Representatives of the State of Georgia and as Rep

resentatives of the class of citizens who are presently

serving as members of the House of Representatives

of the State of Georgia; George T . S m it h , individually

and as Speaker of the House of Representatives of the

State of Georgia and as Chairman of the Rules Com

mittee of the House of Representatives of the State of

Georgia and as Chairman of the Challenge Committee

appointed to consider the seating of Julian Bond, et al.,

On A ppeal prom t h e U nited S tates D istrict C ourt for

t h e N orthern D istrict of Georgia (A tlanta D ivisio n )

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT AND

MOTION TO ADVANCE

H oward M oore, J r.,

8591/2 Hunter Street N.W.,

Atlanta, Georgia, 30314.

L eonard B . B oudin ,

V ictor R abinow itz,

30 East 42nd Street,

New York, New York, 10017.

Attorneys for Appellants,

I N D E X

PAGE

Jurisdictional Statement .............................. 1

Opinions Below . . .............................................. 2

Jurisdiction ..................................... 2

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved... 3

Questions Presented ....................... 4

Statement of the C ase ................ ............................. 4

The Questions Are Substantial ....................... 7

Conclusion .......... 11

Motion To Advance ................................................. 12

Appendix A—Constitutional Provisions and Stat

utes Involved...................................... 14

Appendix B—Opinions Below ................................. 18

Appendix C—Judgment Below ............................... 67

Citations

Cases :

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 ......................... 11

Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186 ............................... 3, 9

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U. S.

278 ................ 11

Cummings v. Missouri, 4 Wall. (71 U. S.) 277....... 10

Florida Lime and Avocado Growers v. Jacobsen,

362 U. S. 73 ................................................. 3

Ex parte Garland, 4 Wall. (71 U. S.) 333 ....... .. 10

Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 64 . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U. S. 233.... 8

Idlewild Bon Voyage Liquor Corp. v. Epstein,

370 TL S. 715............................................... 3

11

PAGE

Kingsley In t’l Pictures Corp. v. Regents, 360 U. 8.

684 ...................................................................... 8

Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 353 U. S.

252 .......... 8

Lindsey v. Washington, 301 IJ. S. 397 .................. 10

Pennsylvania v. Nelson, 350 U. S. 497 .................. 8

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254.... 8

In re Sawyer, 360 U. S. 622 .................................. 8

Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners of New Mex

ico, 353 U. S. 232 ............................................... 8

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516..................... 8

Toombs v. Portson, 241 F. Supp. 65 .................... 4,13

United States v. Brown, 381 U. S. 437 .......... 10

United States v. Johnson, No. 25 Oct. Term 1965.. 9

United States v. Lovett, 328 U. S. 303 .................... 10

United States v. Rumely, 345 U. S. 4 1 .................... 10

United States v. Seeger, 380 U. S. 163 ................ 9

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357 .................... 8

U nited S tates C o n stitu tio n :

Article 1, Section 10 ............................................2, 4,10

Article IV, Section 4 ........................................... 2, 9

Article VI ............................................................. 8

First Amendment .................................................. 2, 4, 7

Fifth Amendment ................................................ 2

Sixth Amendment ................................................ 2

Thirteenth Amendment ......................................... 2

Fourteenth Amendment ....................................... 2, 4

Fifteenth Amendment ........................................... 2

Ill

PAGE

S ta tu tes :

28 U.S.C. § 1253 .................................................... 3

28 U.S.C. § 1331 ................ ................................... 2

28 U.S.C. §1343(3) and (4) ................................ 2

28 U.S.C. §2201 . .................................................. 2

28 U.S.C. § 2281 .................................................... 2, 6

42 U.S.C. § 1971 ............................... 2

42 U.S.C. § 1983 .................................................... 2

42 U.S.C. § 1988 ........................... 2

50 U.S.C. § 456(j) ........................ 9

50 App. U.S.C.A. § 462 (a) and (b) .................... 6

Voting Eights Act of 1965, Pub. L. No. 110, 89th

Cong., 1st Sess.................................................... 12

R ules of t h e S uprem e Court of t h e U nited S tates :

Rule 16(1) ............................................................. 12

Rule 48 .................................................................. 12

Georgia Constitution :

Article III, Section VII, Paragraph I

(§2-1901, Ga. Code Ann.) .......................... 3,11

Article III, Section VI, Paragraph I

('§ 2-1801, Ga. Code Ann.) ............................... 3

Article III, Section IV, Paragraph V

(§2-1605, Ga. Code Ann.) ................................ 3,11

Article II, Section II, Paragraph I

(§2-801, Ga. Code Ann.) .................................. 3,9

Article III, Section IV, Paragraph VI

(§2-1606, Ga. Code Ann.) ............................... 3

Article VII, Section III, Paragraph VI

(§ 2-5606, Ga. Code Ann.) .................................. 3

IV

PAGE

R ules and R esolutions of th e Georgia H ouse of

R epresentatives :

House Rule 61 ............................. .......................... 4,11

House Resolution 19 ............................................. 4, 10

Oth er A u t h o r it ie s :

Brief of Special Committee Appointed by Associa

tion of the Bar of the City of New York, In the

Matter of Louis Waldman, et al........................ 7,10

Chafee, Free Speech in the United S ta tes ............. 7

111 Cong. Rec.:

25420-22 (daily ed. Oct. 19, 1965) ..................... 9

The New Republic, May 22, 1965 ....................... 9

The New York Times:

Nov. 14, 1962, p. 38 ......................................... 9

Aug. 9, 1964, Sec. IV, p. 8 .............................. 9

IN THE

Bupnm Cmtrt of % Imtefr

O cto b er T erm , 1965

No.

■o

J ulian B ond, D r . M artin L u t h e r K ing , J r ., a n d M rs.

A rel K eyes, fo r them selves jo in tly an d sev e ra lly , an d

fo r a ll o th e rs s im ila r ly s itu a ted ,

Appellants,

v.

J ames “ S l o ppy ” F loyd, W illiam J. “ B il l ” L ee , E d T .

F ulpord, J . T errell W ebb, W . J ones L ane, and D avid

L. N ew ton , individually and as members of the House

of Representatives of the State of Georgia and as Rep

resentatives of the class of citizens who are presently

serving as members of the House of Representatives

of the State of Georgia; George T . S m it h , individually

and as Speaker of the House of Representatives of the

State of Georgia and as Chairman of the Rules Com

mittee of the House of Representatives of the State of

Georgia and as Chairman of the Challenge Committee

appointed to consider the seating of Julian Bond;

G l en n W. E llard, individually and as Clerk of the

House of Representatives of the State of Georgia;

M addox J. H ale, individually and as Speaker Pro-Tern

of the House of Representatives of the State of Georgia;

E lmore C. T h ra sh , individually and as Messenger _of

the House of Representatives of the State of Georgia;

D avid P eeples , individually and as Doorkeeper^ of the

House of Representatives of the State of Georgia; and

B en W. F ortson, individually and as Secretary of State

of the State of Georgia; and J ack T yson, individually

and as Sheriff of the House of Representatives of the

State of Georgia.

On A ppe a l prom t h e U n it e d S tates D istr ic t C o urt por

t h e N o r th er n D istr ic t op G eorgia (A tla n ta D iv is io n )

—-------------o---- —-—-----

Jurisdictional Statement

Julian Bond, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Arel Keyes,

the appellants, having appealed from the order and judg-

2

ment, dated February 14, 1966, of the three-judge court

of the United States District Court for the Northern

District of Georgia, Atlanta Division, which (i) denied

their application for a permanent injunction, (ii) dis

missed appellants King and Keyes as parties for lack

of standing, and (iii) dismissed the complaint of appellant

Bond, submit this statement to show that the Supreme

Court of the United States has jurisdiction of the appeal

and that a substantial question is presented.

Appellants have also moved to advance the argument in

this case, infra, p. 12.

Opinions Below

The opinions below (R. 234-279) have not as yet been

reported, and are set forth in the Appendix, infra, pp. 18

to 66.

Jurisdiction

Appellants brought this action in the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Georgia for a

judgment (i) enjoining the defendants from excluding the

appellant Bond from membership in the House of Repre

sentatives of the General Assembly of Georgia, to which he

was elected on June 16, 1965, (ii) enjoining the enforce

ment of certain provisions of the Georgia Constitution and

a Rule and Resolution of the Georgia House of Representa

tives, and (iii) declaring that the said constitutional provi

sions, legislative action and exclusion from office are

uncontitutional.

The action was brought under Article I, Section 10' and

under Article IV, Section 4 of the United States Constitu

tion, and the First, Fifth, Sixth, Thirteenth, Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution; 28 U. S. C.

§§ 1331, 1343(3) and (4), 2201 and 2281; and 42 U. S'. C.

§§ 1971, 1983 and 1988.

3

The judgment below was made on February 14, 1966 and

entered on February 16, 1966 (infra, p. 68). The notice

of appeal was filed in the district court on February 16,

1966 (R. 283-88).

Jurisdiction of this appeal is conferred by 28 U. S. C.

§ 1253. The following cases sustain the Court’s juris

diction : Baker v. Carr, 369 TJ. S. 186; Idlewild Bon Voyage

Liquor Corp. v. Epstein, 370 U. S. 715; Florida Lime and

Avocado Growers v. Jacobsen, 362 U. S. 73.

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved

The provisions of the Georgia Constitution involved

in this case are as follows:

Article III, Section VII, Paragraph I (§ 2-1901,

Ga. Code Ann.), making the House “ the judge of

the election, returns and qualifications of its mem

bers” , infra, p. 14.

Article III, Section VI, Paragraph I (§ 2-1801,

Ga. Code Ann.), setting forth the members’ qualifi

cations, infra, p. 14.

Article III, Section IV, Paragraph V (§ 2-1605,

Ga. Code Ann.), specifying the oath of office of rep

resentatives, infra, p. 14.

The following provisions of the Georgia Constitution

setting forth the disqualifications for office are also involved

in this case.

Article II, Section II, Paragraph I ('§ 2-801, Ga.

Code Ann.), infra, p. 15.

Article III, Section IV, Paragraph VI (§2-1606,

Ga. Code Ann.), infra, p. 15.

Article VII, Section III, Paragraph VI (§ 2-

5606, Ga. Code Ann.), infra, p. 16.

Q

4

The legislative actions involved in this case are as

follows:

House Rule 61 of the Georgia House of Repre

sentatives adopting the provisions of Article III,

Section VII of the Georgia Constitution, infra, p. 16.

House Resolution 19 of January 10, 1966, exclud

ing Mr. Bond from office, infra, pp. 16-17.

Questions Presented

1. Did the exclusion from elected legislative office of

the appellant Julian Bond solely because of his public

statements on issues of national concern impair his free

dom of speech under the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments.

2. Did that exclusion from office disenfranchise Mr.

Bond’s constituents in violation of the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

3. Does House Resolution 19 disqualifying Mr. Bond

from his elected office constitute an ex post facto law or a

bill of attainder in violation of Article I, Section 10 of the

United States Constitution.

4. Are the provisions of the Georgia Constitution and

statutes, as interpreted by the court below, unconstitution

ally vague under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Statement of the Case

Appellant Julian Bond was elected on June 16, 1965 to

the Georgia House of Representatives as the Representative

from the 136th House District, Fulton County, Georgia, for

the term expiring January 1, 1967 (R. 293). This district

was created pursuant to legislation enacted following the

reapportionment decision of the court below in Toombs v.

5

Fortson, 241 F. Supp. 65 (N. D. Ga. 1965). Mr. Bond re

ceived 82 per cent of the votes cast in an overwhelmingly

Negro district.1

Mr. Bond, a pacifist and Negro, is also the Communica

tions Director of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating

Committee (herein called SNCC), an association dedicated

to racial equality through non-violence.

The other appellants are constituents of Mr. Bond and

sued as representatives of that class in the district. Mrs.

Arel Keyes voted in the election for Mr. Bond; Dr. Martin

Luther King, Jr., a former resident of the district, trans

ferred his voting residence to it on January 24, 1966.

The defendant members, employees and officers of

the state government, excluded Mr. Bond from his

elected office and rejected his offer to take the oath of

office because of statements he made when interviewed

by the press, viz. that he supported a SNCC statement

critical of American involvement in the war in Vietnam;

that when asked for his views on the burning of draft cards,

he “ stated he would not burn his own but admired the

courage of those who did” and that as a pacifist he sup

ported the opposition of others to the war (infra, pp. 23-24).

By reason of these statements, exclusion proceedings

against Mr. Bond were conducted by the Georgia House

of Representatives upon petitions charging, inter alia, that

“ Mr. Bond’s actions and statements gave aid and comfort

to the enemies of the United States, and also violated the

1 In a subsequent election conducted on February 23, 1966

Mr. Bond was reelected without opposition. A few minutes before

adjournment on February 18, 1966 the House amended its rules and

authorized its speaker to appoint a committee during the House recess

to determine election contests.

2 The SNCC statement is set forth in full in the majority opinion

below (infra, pp. 21-23).

6

Selective Service Laws, 50 App. U. S. C. A. § 462(a) and

(b), and tended to bring discredit and disrespect on the

House of Representatives” (infra, p. 24). It was also

charged “ that the statements and views of Mr. Bond dis

qualified him to take the oath to support the Constitution

of the United States and the Constitution of Georgia, as

is required of a member of the House of Representatives”

(infra, p. 25).

Hearings were conducted before a special committee of

the House which, by majority report, recommended that

Mr. Bond be excluded (infra, p. 19). The House, adopting

that report, excluded him by passing House Resolution 19

by majority vote on January 10, 1966 (infra, p. 19).

Mr. Bond and his constituents thereupon instituted this

action for injunctive relief and a declaratory judgment that

the legislature’s action was unauthorized by the state Con

stitution and violated their rights under the federal Con

stitution. A three-judge court was convened under 28

U. 8. C. 2281.

On February 14, 1966, the court rendered final judg

ment against the appellants. It unanimously held that it

had jurisdiction because the plaintiffs had asserted substan

tial First Amendment rights (infra, p. 37). The court,

Chief Judge Tuttle dissenting, struck from the complaint

the names of the appellants other than Mr. Bond on the

ground that they lacked “ such a direct interest in the liti

gation as would give them standing to bring the complaint”

(infra, p. 27).8

On the merits, the court was also divided. The majority

agreed that “ [t]he substantial issue in the case rests on

the guaranty of freedom of speech or to dissent under the

3 It held, too, that Dr. King, although a resident, was not a

registered voter (ibid.).

First Amendment as that amendment has long been applic

able to the state under the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment” (infra, p. 28). Nevertheless, it held

that “ his [Bond’s] statements and affirmation of the

8NCC statement as they bore on the functioning of the

Selective Service System could reasonably be said to be

inconsistent with and repugnant to the oath which he was

required to take” (infra, p. 40).

Chief Judge Tuttle, dissenting, was of the view that

since substantial federal constitutional issues of freedom

of speech were involved, the court was under a duty to con

strue the Georgia constitutional provisions “ with an eye

to the avoiding of the constitutional question if possible”

(infra, p. 54). He concluded that the Constitution ex

plicitly stated the qualifications for legislative office, which

were met by Mr. Bond, and could not be construed to au

thorize rejection from elected office for a reason not speci

fied, vis., for making a lawful public statement upon foreign

affairs (infra, p. 65).

The Questions Are Substantial

1. This is the first case before the Court in which a

legislative body has refused to seat an elected representa

tive because of his public expression of opinion. Significant

precedents, never subjected to judicial review, are authori

tatively recognized as raising important questions of free

dom of speech and of franchise.4

The belief of the majority below that the “ SNCC state

ment is at war with the national policy of this country”

4 John Wilkes in 1768 (See Chafee, Free Speech in the United

States [1941], 242-247.) ; Victor L, Berger in 1919 (See Chafee,

247-269.) ; In the Matter of Louis Waldman, August Claessens,

Samuel A. De Witt, Samuel Orr and Charles Solomon (before the

Assembly Judiciary Committee, New York State Legislature),

Brief of Special Committee Appointed by the Association of the

Bar of the City of New York, headed by former Justice (later Chief

Justice) Hughes. (See also Chafee, 269-282.)

8

(infra, p. 38) conflicts with our conception of a demo

cratic society; see Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297

U. S. 233, 247, 250. Its view that the legislature’s inter

ference could be justified as having ‘ ‘ a rational evidentiary

basis” (infra, p. 37) incorrectly assumes that the freedom

of speech of an elected legislator depends not upon the

First Amendment but upon the judgment of his colleagues.

There is no suggestion in this case of any danger which

could justify a direct impairment of First Amendment

rights. See, e.g., Whitney v. California, 274 IT. S. 357, 372

(Mr. Justice Brandeis, concurring opinion); Thomas v.

Collins, 323 U. S. 516, 530.

The reference of the majority below to a “ rational evi

dentiary basis ’ ’ may have been based upon the unarticulated

assumption that the interference with speech was only

indirect. But the application of even this test could not

support the exclusion of Mr. Bond from elected office and

the resulting interference with his constituents’ exercise

of their right to vote. There was no rational basis for the

legislature’s action under the critical factual analysis

employed by this Court in analogous situations; Konigsberg

v. State Bar of California, 353 IT. S. 252; Schware v. Board

of Bar Examiners of New Mexico, 353 U. S. 232; In re

Sawyer, 360 U. S. 622. The impairment of free speech

cannot be veiled by a reference to the doctrines of “ separa

tion of powers” and “ our system of federalism” infra,

p. 35. First, the supremacy clause is an equally controlling

doctrine, see Pennsylvania v. Nelson, 350 U. S. 497; second,

there is “ a profound national commitment to the principle

that debate on jjublic issues should be uninhibited, robust

and wide open.” New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U. 8.

254, 270; see also Kingsley In t’l Pictures Corp. v. Regent,

360 U. S. 684, 688-689. If the legislature’s conduct impairs

constitutional rights, the doctrines enunciated by the court

below are no defense. To hold otherwise is to reject federal

judicial review of state unconstitutional action.

9

The SNCC statement pales before expressions on the

same subject by some of the most distinguished public

figures,5 Its suggestion of exemption for conscientious ob

jectors and of alternative civilian work is already law; see

50 U. S. 0. 456( j ) ; United States v. Seeger, 380 U. S. 163.

The SNCC statement was lawful; so was Mr. Bond’s

approval of it. In any event, he could not be disqualified

for office, absent a criminal conviction in court, Georgia

Constitution, Article II, Section II, Paragraph I (infra,

p. 15).6

2. Mr. Bond as an elected legislator had an enhanced

right and a duty to his constituents to speak out on public

issues even if his views had not been solicited by the

press; see Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 64.7 An elected

representative must communicate freely with his constitu

ents as well as engage in legislative debate. He does not

enjoy the ordinary citizen’s prerogative of silence. To

circumscribe the legislator’s rights, as did the Georgia

legislature, is to interfere with representative democracy

and equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth

Amendment in no less degree than by the malapportionment

which has been the subject of this Court’s recent decisions;

see, e.g., Baker v. Carr, supra.8

5 See, e.g., Senator Wayne Morse in 111 Cong. Rec. 25420-22

(daily ed. Oct. 19, 1965) ; Circuit (formerly Chief) Judge Henry

W. Edgerton in The New Republic, May 22, 1965; The New York

Times, November 14, 1962, p, 38; August 9, 1964, Sec. IV, p. 8.

6 Mr. Bond’s statement to the legislative committee that he

never advocated “that people should break laws” (infra, p. 53) is

not questioned by the court below.

7 See also United States v. Johnson, No. 25, Oct. Term, 1965,

emphasizing the need to protect legislators’ freedom in matters

affecting their special responsibilities.

8 While this is a sufficient federal question under Baker v. Carr,

supra, appellants would also urge, at least in the present context,

reconsideration of the Court’s view that the impairment of the

constitutional guaranty of a republican form of government, under

Article IV, § 4, does not raise a justiciable question.

10

The conception that the majority of a legislature pos

sesses a veto power over the choice of the electorate is to

reject “ the essence of constitutional representative govern

ment.” 9 Nor can the majority secure this veto obliquely

by denying the member-elect the privilege of taking the

oath “ because of any alleged opinion, state of mind or

intent, claimed to be inconsistent with the oath” (ibid.).

The majority was also in error in ruling that Mr.

Bond’s constituents lacked standing to sue (infra, pp. 26-

27). They were proper parties under this Court’s decisions

because Mr. Bond’s expulsion deprived his co-appellants

and their class in violation of the equal protection clause

of representation in the Georgia House of Representatives.

3. House Resolution 19, excluding Mr. Bond from office,

is an ex post facto law and a bill of attainder prohibited by

Article I, Section 10 of the Constitution. It is a legislative

act in the classic sense, although promulgated by a single

house of the legislature.10 It singles out an individual

because of imputed past misdeeds of a political nature,

stigmatizes him as disloyal, and punishes him by expulsion

from office and his constituents by loss of suffrage. The

resolution is plainly unconstitutional under the Court’s

decisions on bills of attainder and ex post facto laws;

United States v. Brown, 381 U. S. 437; Ex parte Garland,

4 Wall. (71 U. S.) 333; Cummings v. Missouri, 4 Wall. (71

U. S.) 277; United States v. Lovett, 328 U. S. 303; Lindsey

v. Washington, 301 G. S. 397.

4. There was sound basis for Chief Judge Tuttle’s dis

senting view that the exclusion of Mr. Bond was not author

ized by the state Constitution and statute (infra, p. 65).

This construction of state law was impelled by the need to

avoid “ deciding the grave federal question” (infra, p. 66).

Cf. United States v. Rumely, 345 U. S. 41. Its adoption

below would have required judgment in appellants’ favor

9 See the Brief of Special Committee, pp. 4, 9, referred to in foot

note 4.

10 See United States v. Lovett, infra, at p. 315.

11

since the district court correctly held that it had juris

diction.

The majority’s contrary interpretation of Georgia law

raises a serious question of vagueness under the Fourteenth

Amendment. It would turn precise qualifications for

office 11 into an unlimited discretion by a legislative major

ity to determine qualifications on an ad hoc basis. It would

turn a constitutionally prescribed promissory oath 12 into a

license to investigate the member’s associations and beliefs.

The pemiciousness of vagueness in the First Amendment

area, particularly where the oath restricts political expres

sion, is obvious, Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368

U. S. 278; Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360. The injury is

magnified when one considers the historically dangerous

effect of the test oath for public office. As applied here, it

negates the electoral decision of the people and usurps their

inherent censorial power over their elected representatives.

CONCLUSION

The questions are substantial and the Court should

note probable jurisdiction.

Respectfully submitted,

H oward M oore, J r .,

859% Hunter Street N.W.,

Atlanta, Georgia, 30314.

L eonard B . B o u d in ,

V ictor R a bin o w itz ,

30 East 42nd Street,

New York, New York, 10017.

Attorneys for Appellants.

March, 1966.

11 Article III, Section VII, Paragraph I of the Georgia Con

stitution, infra, p. 14, and House Rule 61, infra, p. 16.

12 Article III, Section IV, Paragraph V of the Georgia Constitu

tion, infra, p. 14.

12

IN THE

( t e r t itf t ip In t t f f r

O cto b e r T erm , 1965

No.

----------------------- 1).------ — -------------

J ulian B ond, D r. M artin L u th er K ing , J r., a n d M rs.

A rel K eyes, f o r them selves jo in tly an d severally , and

fo r all o th e rs s im ila r ly s itu a ted ,

Appellants,

v.

J ames “ S l o ppy ” F loyd, et al.

O n A p p e a l erom t h e U n it e d S tates D istr ic t C ourt eor

t h e N o r th er n D istrict1 of G eorgia (A tlanta D iv is io n )

————■—-—■—o—-----------------

M otion to A dvance

Pursuant to Rule 48 of the Rules of this Court, appel

lants respectfully move this Court (i) to reduce the ap

pellees’ time to move under Rule 16(1), (ii) to advance

the case for argument to the week of May 2, 1966, if the

Court notes probable jurisdiction or postpones considera

tion of jurisdiction, and (iii) to dispense with the printing

of the record.

The reason for this application is the extraordinary

public importance of this case. Both state and federal

elections will be held this Fall in which candidates should

not be threatened with disqualification either for express

ing their views or as a device for evading federal court de

cisions and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Pub. L. No. 110,

13

Motion to Advance

89th Cong., 1st Sess. There is also a continuing and

irreparable injury to appellants by reason of Mr. Bond’s

continued exclusion from office. While the general session

of the legislature ended on February 18, 1966, its standing

committees continue to function and there is a strong-

probability that a special legislative session will be called

by the Governor by reason of motions now pending in

Toombs v. Fortson, 241 F. Supp. 65 (N. D. Ga. 1965).

Unless this case is advanced it is not likely to be decided

on the merits before the expiration of Mr. Bond’s term

of office on December 31, 1966 and hence may he mooted.

An early decision by the Court will prevent protracted

litigation which may otherwise result from repeated elec

tions of Mr. Bond and rejections by the legislature.

Since the only issues, those of law, are adequately pre

sented by the opinions below, the printing of the record

is unnecessary.

W herefore, appellants respectfully pray that the Court

grant this motion to advance.

Respectfully submitted,

H oward M oore, J r .,

8591/2 Hunter Street N.W.,

Atlanta, Georgia, 30314.

L eonard B . B oudin ,

V ictor R abinow itz,

30 East 42nd Street,

New York, New York, 10017.

Attorneys for Appellants.

March, 1966.

14

APPENDIX A

Constitution and Legislative Acts

Article III, Section VII, Paragraph I, of the Georgia

Constitution provides in pertinent part as follows:

“ Election, returns, etc.; disorderly conduct.—

Each House shall he the judge of the election, re

turns, and qualifications of its members and shall

have power to punish them for disorderly behavior,

or misconduct, by censure, fine, imprisonment, or

expulsion, hut no member shall he expelled, except

by a vote of two-thirds of the House to which he

belongs.” (2-1901, Ga. Code Ann.)

Article III, Section VI, Paragraph I, of the Georgia

Constitution provides in pertinent part as follows:

“ Qualifications of representatives.—The Repre

sentatives shall be citizens of the United States who

have attained the age of twenty-one years, and who

shall have been citizens of this State for two years,

and for one year residents of the counties from

which elected. (2-1801, Ga. Code Ann.)

Article III, Section IV, Paragraph V, of the Georgia

Constitution provides in pertinent part as follows:

“ Oath of members.—Each senator and repre

sentative, before taking his seat, shall take the fol

lowing oath, or affirmation, to wit: ‘I will support

the Constitution of this State and of the United

States, and on all questions and measures which

may come before me, I will so conduct myself, as

will, in my judgment, be most conducive to the in

terests and prosperity of this State.” (2-1605, Ga.

Code Ann.)

15

Appendix A—Constitution and Legislative Acts

Article II, Section II, Paragraph I, of the Georgia Con

stitution provides in pertinent part as follows:

“ Registration of electors; who disfranchised.—

The General Assembly may provide, from time to

time, for the registration of all electors, hut the fol

lowing classes of persons shall not be permitted to

register, vote, or hold any office, or appointment of

honor, or trust in this State, to wit: 1st. Those

who shall have been convicted in any court of com

petent jurisdiction of treason against the State, of

embezzlement of public funds, malfeasance in office,

bribery or larceny, or of any crime involving moral

turpitude, punishable by the laws of this State with

imprisonment in the penitentiary, unless such per

sons shall have been pardoned. 2nd. Idiots and

insance persons.” (2-1801, Ga. Code Ann.)

Article III, Section IV, Paragraph VI, of the Georgia

Constitution provides in pertinent part as follows:

“ Eligibility; appointments forbidden.—No per

son holding a military commission, or other appoint

ment, or office, having an emolument, or compensa

tion annexed thereto, under this State, or the United

States, or either of them except Justices of the

Peace and officers of the militia, nor any defaulter

for public money, or for any legal taxes required

of him shall have a seat in either house; nor shall any

Senator, or Representative, after his qualification

as such, be elected by the General Assembly, or ap

pointed by the Governor, either with or without the

advice and consent of the Senate, to any office or

appointment having any emolument annexed thereto,

during the time for which he shall have been elected,

unless he shall first resign his seat, provided, how

ever, that during the term for which he was elected

16

Appendix A—Constitution and Legislative Acts

no Senator or Representative shall be appointed to

any civil office which has been created during such

term.” (2-1601, da. Code Ann.)

Article VII, Section III, Paragraph YI, of the deorgia

Constitution provides in pertinent part as follows:

‘ ‘ Profit on public money.—The receiving, directly

or indirectly, by any officer of State or county, or

member or officer of the deneral Assembly of any

interest, profits or perquisites, arising from the use

or loan of public funds in his hands or moneys to

be raised through his agency for State or county

purposes, shall be deemed a felony, and punishable

as may be prescribed by law, a part of which punish

ment shall be a disqualification from holding office.”

(2-5606, da. Code Ann.)

House Rule 61 of the deorgia House of Representatives

provides in pertinent part as follows:

“ Each house shall be the judge of the election,

returns, and qualifications of its members and shall

have power to punish them for disorderly behavior,

or misconduct, by censure, fine, imprisonment, or ex

pulsion ; but no member shall be expelled, except by

a vote of two-thirds of the House to which he be

longs.”

House Resolution 19 of January 10, 1966 of the deorgia

House of Representatives provides in pertinent part as

follows:

“ Relative to the matter of the seating of Repre

sentative-Elect Julian Bond; and for other purposes.

“ W hereas, a special committee created pursuant

to H.R. No. 7 which was appointed for the purpose

17

Appendix A—Constitution and Legislative Acts

of holding a hearing on petitions challenging and

contesting the seating of Representative-Elect Julian

Bond of the 136th District has conducted a hearing

in said matter; and

“ W hereas, said committee has submitted a re

port in which it is recommended that Representa

tive-Elect Julian Bond not be allowed to take the

oath of office as a Representative of the House of

Representatives and that he not be seated as a mem

ber of the House of Representatives.

“ Now, THEREFORE', BE IT RESOLVED BY THE HOUSE

of R epresentatives th a t th e re p o r t o f the a fo re sa id

com m ittee is h e re b y a d o p ted a n d th e reco m m en d a

tio n s co n ta in ed th e re in sh a ll be follow ed.

“ B e it f u r t h e r resolved that Representative-

Elect Julian Bond shall not be allowed to take the

oath of office as a member of the House of Repre

sentatives and that Representative-Elect Julian

Bond shall not be seated as a member of the House

of Representatives.

“ B e it f u r t h e r resolved that the Clerk of the

House is hereby instructed to immediately transmit

a copy of the aforesaid report and a copy of this

resolution to the Governor, to the Secretary of

State and to Representative-Elect Julian Bond.”

18

APPENDIX B

Opinions Below

IN THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or t h e N orthern D istrict op Georgia

A tlanta D ivision

Civil Action No. 9895

—--------------- o--------------------

J ulian B ond, Dr. M artin L u th er K ing , J r ., and M rs. A rel

K eyes, for themselves jointly and severally, and for all

others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs,

v.

J ames “ S l o ppy” F loyd, et al.,

Defendants.

—---------- ------- o—-----------------

Before T uttle and B ell , Circuit Judges, and

M organ, District Judge.

B ell , Circuit Judge an d M organ, District Judge-.

Opin io n and Order

Mr. Bond, one of the plaintiffs in this matter and a

Negro, was refused his seat as a member of the House of

Representatives of the General Assembly of Georgia. He

was a Representative-elect, having been duly elected by

the voters of House District No. 136 for the session of the

General Assembly commencing January 10, 1966. This

19

Appendix B—Opinions Below

was a special election for a one year term made necessary

by the reapportionment decision of this court. Toombs v.

Fortson, N. D., Ga., 1965, 241 F. Supp. 65.

On the first day of the session, at which time Mr. Bond

and other members of the House were to take the oath of

office, Mr. Bond was asked to step aside because of chal

lenges to his qualifications having been filed by seventy-five

of the two-hundred-five members of the House. Alter the

other members were sworn, including seven Negro repre

sentatives, petitions protesting the seating of Representa

tive-Elect Bond were referred by the Speaker of the House

to a special committee designated to hear the contest. This

committee, after a hearing, recommended that he not be

seated. This recommendation was accepted by the House

and he was denied his seat by a vote of one hundred eighty-

four to twelve.

Dr. King and Mrs. Keyes, the other plaintiffs, seek

along with Mr. Bond to represent the citizens and voters of

House District No. 1.36 as a class, and it is affirmatively

alleged that they are Negro citizens of House District

No. 136 and that they are registered voters. They allege

that there are common questions of law and fact affecting

the civil rights of Negroes to vote and to have members

of their race represent them in the House of Representa

tives of the State of Georgia. It is undisputed that Dr.

King and Mrs. Keyes are residents of the district, but it is

also undisputed that Dr. King is not registered to vote in

the district but in the House District No. 132.

The defendants are the Speaker of the House, the

Speaker Pro-Tern, several members of the House repre

senting the membership, certain officers of the House, and

the Secretary of State of the State of Georgia. Jurisdiction

for declaratory and injunctive relief is asserted under 28

USCA, §§ 1331, 1343(3), 1343(4), and 2201; and 42 HSCA,

§§ 1971(d), 1983, and 1988. Three-Judge District Court

jurisdiction was premised on 28 HSCA, § 2281 by a claim

20

Appendix B—Opinions Below

that the provision of the Georgia Constitution which per

mits the members of the House to judge the qualifications

of its members, and House Rule 61 which embodies the same

provision are unconstitutionally vague, or were unconstitu

tionally administered with respect to Mr. Bond.

The additional causes of action set forth in the com

plaint were refined by briefs into claims that Mr. Bond

was barred from membership because he was a Negro;

that the action of the House denied him his First Amend

ment right to free speech; that he was denied procedural

due process as guaranteed by the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment; that he was denied substantive due

process in that there was no rational basis for the action

of the House; that the House resolution barring Mr. Bond

constituted an ex post facto law and a hill of attainder;

and that the House action deprived the residents of the

House District No. 136 of a republican form of government,

equal protection of the law under the Fourteenth Amend

ment, and the right as Negroes under the Fifteenth Amend

ment to vote. The prayer is that defendants he enjoined

from excluding Mr. Bond from membership in the House.

The defendants, by motion, have denied the jurisdiction

of the court. Additionally, in the alternative, they have

moved to dismiss Dr. King and Mrs. Keyes as plaintiffs.

They have also answered the complaint. It was stipulated

that a final judgment might be rendered on the pleadings,

the stipulated facts and such other evidence as was intro

duced on the hearing of this matter. We thus proceed to

final disposition.

The facts which gave rise to the challenge to Mr. Bond

stem from a statement issued on January 6, 1966 by the

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, an organiza

tion active in the civil rights field. Mr. Bond is and was

Communications Director of this organization. After the

statement was issued, Mr. Bond, upon inquiry, advised the

news media that he supported the statement in its entirety.

21

Appendix B—Opinions Below

He added that he admired the courage of persons who

burned their draft cards; that he was a pacifist who was

eager and anxious to encourage people not to participate

in the war in Viet Nam for any reason that they might

choose; and said that as a second class citizen he did not

feel that he should be required to support the war in Viet

Nam.

The SNNC statement follows in full:

“ The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Commit

tee has a right and a responsibility to dissent with

United States foreign policy on an issue when it sees

fit. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Commit

tee now states its opposition to United States’ in

volvement in Viet Nam on these grounds:

“ We believe the United States government has

been deceptive in its claims of concern for freedom

of the Vietnamese people, just as the government has

been deceptive in claiming concern for the freedom

of colored people in such other countries as the Do

minican Eepublic, the Congo, South Africa, Rhodesia

and in the United States itself.

“ We, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Com

mittee, have been involved in the black people’s strug

gle for liberation and self-determination in this

country for the past five years. Our work, particu

larly in the South, has taught us that the United

States government has never guaranteed the freedom

of oppressed citizens, and is not yet truly determined

to end the rule of terror and oppression within its

own borders.

“ We ourselves have often been victims of vio

lence and confinement executed by United States

government officials. We recall the numerous per

sons who have been murdered in the South because

of their efforts to secure their civil and human rights,

22

Appendix B—Opinions Below

and whose murderers have been allowed to escape

penalty for their crimes.

“ The murder of Samuel Young in Tuskegee, Ala.,

is no different than the murder of peasants in Viet

Nam, for both Young and the Vietnamese sought,

and are seeking, to secure the rights guaranteed

them by law. In each case the United States govern

ment bears a great part of the responsibility for

these deaths.

“ Samuel Young was murdered because United

States law is not being enforced. Vietnamese are

murdered because the United States is pursuing an

aggressive policy in violation of international law.

The United States is no respecter of persons or law

when such persons or laws run counter to its needs

and desires.

“ We recall the indifference, suspicion and out

right hostility with which our reports of violence have

been met in the past by government officials.

“ We know that for the most part, elections in

this country, in the North as well as the South, are

not free. We have seen that the 1965 Voting Eights

Act and the 1964 Civil Rights Act have not yet been

implemented with full federal power and sincerity.

“ We question, then, the ability and even the desire

of the United States government to guarantee free

elections abroad. We maintain that our country’s

cry of ‘preserve freedom in the world’ is a hypo

critical mask behind which it squashes liberation

movements which are not bound, and refuse to be

bound, by the expediencies of United States cold war

policies.

“ We are in sympathy with, and support, the men

in this country who are unwilling to respond to a

military draft which would compel them to contribute

their lives to United States aggression in Viet Nam

23

Appendix B—Opinions Below

in the name of the ‘freedom’ we find so false in this

country.

“ We recoil with horror at the inconsistency of a

supposedly ‘free’ society where responsibility to

freedom is equated with the responsibility to lend

oneself to military aggression. We take note of the

fact that 16 percent of the draftees from this country

are Negroes called on to stifle the liberation of Viet

Nam, to preserve a ‘democracy’ which does not exist

for them at home.

“ We ask, where is the draft for the freedom fight

in the United States?

“ We therefore encourage those Americans who

prefer to use their energy in building democratic

forms within this country. We believe that work

in the civil rights movement and with other human

relations organizations is a valid alternative to the

draft. We urge all Americans to seek this alterna

tive, knowing full well that it may cost them lives—

as painfully as in Viet Nam.”

On the same day a newspaper reporter asked Mr. Bond

for his views on the subject of the burning of draft cards.

He stated that he would not burn his own but admired the

courage of those who did.

During a taped interview with a representative of the

media, Mr. Bond, after endorsing the 8NCC statement was

asked why he endorsed it, and his answer was as follows:

“ Why, I endorse it, first, because I like to think

of myself as a pacifist and one who opposes that war

and any other war and eager and anxious to encour

age people not to participate in it for any reason

that they choose; and secondly, I agree with this

statement because of the reason set forth in it—

because I think it is sorta hypocritical for us to main-

24

Appendix B—Opinions Below

tain that we are fighting for liberty in other places

and we are not guaranteeing liberty to citizens inside

the continental United States.”

When asked if he thought his views were at variance

with the duties that might be required of him as a Repre

sentative in the House of Representatives of the State of

Georgia, Mr. Bond replied:

“ Well, I think that the fact that the United States

Government fights a war in Viet Nam, I don’t think

that I as a second class citizen of the United States

have a requirement to support that war. I think

my responsibility is to oppose things that I think

are wrong if they are in Viet Nam or New York,

or Chicago, or Atlanta, or wherever.”

These facts were introduced before the House commit

tee hearing the challenge. Mr. Bond was represented by

counsel at the hearing and testified. He reaffirmed his

adherence to all of these statements at the hearing and

stated that they were still his views. There was no evi

dence then nor at the hearing before this court that Mr.

Bond had receded in any way from his views. However,

by way of explanation, he did state to the House committee

that he had never suggested or advocated that anyone

burn his draft card. He stated his willingness and desire

to take the prescribed oath to support the Constitution

of the United States and the State of Georgia.

The petitions challenging Mr. Bond which were before

the special committee of the House contain several grounds,

including the contention that Mr. Bond’s actions and state

ments gave aid and comfort to the enemies of the United

States, and also violated the Selective Service laws, 50'

App., USCA, § 462(a) and (b), and tended to bring dis

credit and disrespect on the House of Representatives.

25

Appendix B—Opinions Below

The challenge was also on the basis that the statements

and views of Mr. Bond disqualified him to take the oath

to support the Constitution of the United States and the

Constitution of Georgia as is required of a member of

the House of Representatives. The theory was that Mr.

Bond’s statements were so repugnant to and inconsistent

with his oath as to make it apparent that he could not

honestly take the oath. This theory presents the central

issue in the case.

P ending M otions

Defendants moved to dismiss the complaint on the

ground that the court lacks jurisdiction over the subject

matter. Their view is that the determination of the qualifi

cations of a member of the State House of Representatives

is a matter which state law vests in the sole and exclusive

jurisdiction of the House of Representatives, and that

the federal questions asserted are insubstantial. They

urge that the absence of any substantial question concern

ing deprivation of federally protected rights indicates that

the action of the House is not subject to federal judicial

review.

The extent of review under the circumstances will be

discussed hereinafter under the merits of the controversy.

However, we do hold that the court has jurisdiction over

the subject matter of the complaint. It could hardly be

argued that the House could refuse to seat a member be

cause of his race or for any other reason amounting to

an invidious discrimination under the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Cf. Baker v. Carr,

1962, 369 U. S, 186, 82 S. Ct. 691, 7 L. Ed. 2d 663. The

denial of a seat to a Negro representative-elect would also

violate the Fifteenth Amendment. Cf. Gomillion v. Light-

foot, 1960, 364 U. S. 339, 81 S. Ct. 125, 5 L. Ed. 2d 110. We

think it follows that the court has jurisdiction over a

26

Appendix B—Opinions Below

denial of First Amendment rights by the state, and that

the federal rights asserted here are not so insubstantial

as to warrant our refusing jurisdiction. The motion of

the state to dismiss will be overruled and an order may

be presented accordingly.

The defendants also have motions pending to strike

the plaintiffs King and Keyes on the ground that they

do not have such a direct interest in the litigation as would

give them standing. They base their standing on an ab

sence of representation in the House because Mr. Bond

was deprived of his seat. The Governor has called an

election for February 23, 1966 to fill the vacant seat,1

It is settled that one seeking to challenge the constitu

tionality of the statute must show that he has sustained

or is in danger of sustaining some immediate direct in

jury. Liverpool, N. Y. and P. Steamship Company v.

Comm, of Emigration, 1885, 113 TJ. S. 33, 5 S. Ct. 352, 28

L. Ed. 899; Commonwealth of Massachusetts v. Mellon,

1923, 262 U. S. 447, 43 S. Ct. 597, 67 L. Ed. 1078. Dr. King

and Mrs. Keyes have not “ . . . alleged such a personal

stake in the outcome of the controversy as to assure that

concrete adverseness which sharpens the presentation of

issues . . . ” necessary in determining constitutional ques

tions. Baker v. Carr, supra.

In a case involving the temporary lack of representa

tion because a United States Senator had been denied

his seat pending inquiry into his election and, qualifica

tions, Barry v. United States, 1929, 279 U. S. 597, 49 S. Ct.

452, 73 L. Ed. 867, the court said:

“ The temporary deprivation of equal repre

sentation which results from the refusal of the

1 Mr. Bond is a candidate for the vacant seat and is the only

candidate. The qualifications closed on February 7, 1966. The

General Assembly will adjourn its present session on Friday, Feb

ruary 18, 1966. There will be no other regular session of the

General Assembly during the year 1966.

27

Appendix B—Opinions Below

Senate to seat a member pending inquiry as to his

election or qualifications is the necessary conse

quence of the exercise of a constitutional power,

and no more deprives the State of its ‘equal suf

frage’ in the constitutional sense than would a vote

of the Senate vacating the seat of a sitting member

or a vote of expulsion.”

We are of the opinion that plaintiffs King and Keyes do

not have such a direct interest in the litigation as would give

them standing to bring the complaint. This is particularly

so in view of the fact that the complaint of Mr. Bond alone

will resolve every conceivable issue. Moreover, I)r. King is

not a registered voter in the House District in question.

The motion of the state to dismiss as to these two plaintiffs

will be granted and an order may be presented accordingly.

T h e M erits

The contention that Mr. Bond was denied his seat be

cause of his race was resolved adversely to him from the

bench during the hearing of this matter. To support this

contention it was urged that Mr. Bond was a Negro; that

SNCC was a militant civil rights organization; and that

the question of race was inextricably related to each and

every statement forming the basis of the challenge. This

logic would create license in the name of race. Furthermore,

seven Negroes, as stated, were seated on the same day as

representatives. Two served on the special challenge com

mittee at the request of Mr. Bond; two Negro senators ap

peared before the committee as character witnesses for him;

and two of the Negro representatives spoke on the floor of

the House for him before the final vote. The charge of

racial discrimination and thus of denial of equal protection

of the law is without foundation in fact.

28

Appendix B—Opinions Below

This ruling also disposes of any claim that Mr. Bond or

the citizens and voters of House District No. 136 have been

deprived of any right as Negroes under the equal protec

tion clause of the Fourteenth Amendment or under the

Fifteenth Amendment. For the reasons stated on the stand

ing question we reject also the contention that the action

of the House denied them a republican form of government.

This is not even a justiciable issue Baker v. Carr, supra.

The substantial issue in the case rests on the guaranty

of freedom of speech or to dissent under the First Amend

ment as that amendment has long been applicable to the

states under the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Gitlow v. New York, 1925, 268 IT. S. 652, 45

8. Ct. 625, 69 L. Ed. 1138; De Jonge v. Oregon, 1937, 299

U. 8. 353, 57 S. Ct. 255, 81 L. Ed. 278. But the inquiry does

not end simply on the question of deprivation of First

Amendment rights per se. Rather the inquiry must be in

the context of two fundamental principles of government:

separation of powers and state government under our

system of federalism. The right of free speech would not

long exist absent a government founded on these principles.

James Madison writing in Federalist No. 47 said with

respect to the separation of powers doctrine:

“ The accumulation of all powers, legislative, ex

ecutive, and judiciary in the same hands, whether of

one, a few or many, and whether heredity, self-ap

pointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the

very definition of tyranny.

And from the beginning states have claimed and enjoyed

the protection of the separation of powers principle as be

tween their respective branches of government. This, to

date, has been a part of our federalism.

Georgia adopted the separation of powers principle in

its first Constitution. Art. I, Const, of 1777. McElreath,

29

Appendix B—Opinions Below

Constitution of Ga., § 239, p. 229. The Constitution of 1789,

Art. I, § XIII, McElreath, supra, § 314, p. 243, provided that

each House of the state legislature would be the judge of

the elections, returns and qualifications of its own mem

bers and have the power to expel or punish for disorderly

behavior. Similar provisions have been included in every

other Georgia Constitution. Ga. Const, of 1798, Art. I,

§ VIII, McElreath, $ 364, p. 253; Const, of 1861, Art. II,

§ IY, Par. I, McElreath, § 484, p. 286, Const, of 1865, Art.

II, $IV, Par. I, McElreath, $ 585, p. 304; Const, of 1868,

Art. Ill, § IV, Par. I, McElreath, $ 709, p. 328; Const, of

1877, Art. Ill, $ VII, Par. I, McElreath, $ 882, p. 361.

“ Each House shall be the judge of the election,

returns, and qualifications of its members and shall

have power to punish them for disorderly behavior,

or misconduct, by censure, fine, imprisonment, or ex

pulsion ; but no member shall be expelled, except by a

vote of two-thirds of the House to which he belongs.”

This language is to be compared with Art. I, $ 5, Clauses

I and 2 of the Constitution of the United States:

“ Each House shall be the Judge of the Elections,

Returns and Qualifications of its own Members, . . . ”

(Clause 1)

“ Each House may determine the Rules of its Pro

ceedings, punish its Members for disorderly Be

havior, and, with the Concurrence of two thirds, ex

pel a Member.” (Clause 2)

The Georgia courts have consistently refused to take

jurisdiction over controversies having to do with the quali

fications of legislators. The Senate or House, as happened

to be the case, was deemed to have exclusive jurisdiction un

der the Georgia Constitution. Rainey v. Taylor, 1928, 166

Ga. 476, 143 S. E. 383; Fowler v. Bostick, 1959, 99 Ga. App.

30

Appendix S —Opinions Below.

428, 108 S. E. 2d 720; and Beatty v. Myrich, 1963, 218 Ga.

629, 129 S. E. 2d 764. This is the general law in this coun

try. Indeed we believe that there is no case to the contrary,

federal or state.

Plaintiff recognizes the separation of powers principle

as such on both the federal and state levels. He argues

however that it exists on the state level only insofar as it

does not conflict with the Federal Constitution and must

therefore give way to First Amendment rights in view of

the vertical application of those rights to the states through

the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. This

is a correct statement of the law subject to whatever rights

were left by the Fourteenth Amendment to the state legis

lative branches for control of their internal affairs under

our system of federalism. We thus must measure Mr.

Bond’s freedom to speak in this frame of reference.

Before attempting to resolve this new and substantial

constitutional question we must concern ourselves with the

threshold question, not asserted by plaintiffs, of whether the

legislature had the power under the state Constitution or

laws to bar Mr. Bond. Our distinguished and able Chief

Judge is of the firm view that no such power existed. He

seems to find the power of expulsion, but limits the power

of judging qualifications to those expressed in the Georgia

Constitution. We believe this to be a restrictive view, un

founded in recognized authority and not in keeping with

our history or the principle of separation of powers.

Judge Story gave the reasons for vesting exclusive juris

diction in the legislative branch in such cases (Story, Comm,

on the Const., Vol. II, §831, p. 294) :

“ It is obvious, that a power must be lodged

somewhere to judge of the elections, returns, and

qualifications of the members of each house com

posing the legislature; for otherwise there could be

no certainty, as to who were legitimately chosen

31

Appendix B—Opinions Below

members, and any intruder, or usurper, might claim

a seat, and thus trample upon the rights, and privi

leges, and liberties of the people. Indeed, elections

would become, under such circumstances, a mere

mockery; and legislation the exercise of sovereignty

by any self-constituted body. The only possible

question on such a subject is, as to the body, in

which such a power shall be lodged. If lodged in

any other, than the legislative body itself, its in

dependence, its purity, and even its existence and

action may be destroyed, or put into imminent

danger. No other body, but itself, can have the

same motives to preserve and perpetuate these

attributes; no other body can be so perpetually

watchful to guard its own rights and privileges from

infringement, to purify and vindicate its own char

acter, and to preserve the rights, and sustain the

free choice of its constituents. Accordingly, the

power has always been lodged in the legislative

body by the uniform practice of England and Amer

ica. ’ ’

The Supreme Court in Be Chapman, 1897, 166 U. S.

661, 17 S. Ct. 677, 41 L. Ed. 1154, a case involving a senate

investigation of the conduct of some of its members, said:

“ Under the Constitution the Senate of the United

States has the power to try impeachments; to judge

of the elections, returns, and qualifications of its

own members; to determine the rules of its pro

ceedings, punish its members for disorderly be

havior, and, with the concurrence of two thirds,

expel a member; and it necessarily possesses the

inherent power of self-protection. ”

32

Appendix B—Opinions Below

We believe a state legislative body necessarily possesses

this same inherent power of self-protection if the separa

tion of powers doctrine is to have any real meaning on

the state level. And self-protection goes to the process

of qualifications as well as expulsion.

In Hiss v. Bartett, 1855, 3 Gray 468, 63 Am. Dec. 768,

the question concerned the legislative power to expel a

member. The Massachusetts Constitution contained no

such power but did contain the power to judge returns,

elections and qualifications. The court said:

“ The authority to be ‘judge of the returns, elec

tions, and qualifications of its own members’, does

not limit their power; they are judges in other re

spects, in all respects.”

Art. I, § 5, of the United States Constitution, as noted,

provides that each House shall be the judge of the elec

tions, returns and qualifications of its own members. Art.

I, § 3 provides that no person shall be a representative

unless he meets certain age, citizenship and residential

requirements. In the Constitutional Convention there was

an attempt to set up affirmative qualifications. During

the debate on that draft which was later rejected, Mr.

Dickinson of Delaware, opposed the formulation because

it would be held to be exclusive. He stated that he was

“ against any recitals of qualifications in the Constitu

tion. It was impossible to make a complete one, and a

partial one would, by implication, tie up the hands of the

Legislature from supplying omissions.” Mr. Wilson of

Pennsylvania took the same view, saying: “ Besides a

partial enumeration of cases will disable the Legislature

from disqualifying odious and dangerous characters.”

(Proceedings in Congressional Record, 80th Congress, First

Session, January 3, 1947, Vol. 93, p. 12, Senate debate on

whether Senator Bilbo of Mississippi was disqualified.)

33

Appendix B—Opinions Below

By way of a historical precedent, Mr. Bilbo was denied

his seat in the United States Senate because, among other

reasons, his views regarding the right of Negroes to vote

were repugnant to the oath he would be required to take.

The Senate did not believe that it was limited to the qual

ifications expressed in the Constitution.

See Willoughby, The Constitutional Law of the United

States, 2nd ed., Yol. I, p. 610, where after discussing in

§340 the subject of qualifications for membership being-

determined by Congress, the author states:

“ The instances that have been cited make it

sufficiently clear that the Senate and House have

repeatedly held it to be proper that they should

consider whether or not persons should be admitted

as Senators or Representatives even though pos

sessing all of the qualifications prescribed by the

Constitution for membership and bringing creden

tials in due form of their election.”

In the case of Senator Reed Smoot of Utah who had

been seated but whose qualifications to continue as a Sen

ator were questioned, the investigation committee recom

mended that he be expelled either for reason of his member

ship in a church that countenanced and encouraged

polygamy and united church and state contrary to the

spirit of the Constitution, or because he had taken an oath

of such a nature and character that he is disqualified from

taking the oath of office required of a United States Sen

ator. The question was raised concerning the ability of

the Senate to add qualifications other than those enumer

ated in the Constitution and was answered in the report

as follows:

“ If his conduct has been such as to be prejudicial

to the welfare of society, of the nation, or its Gov

ernment, he is regarded as being unfit to perform

34

Appendix B—Opinions Below

the important and confidential duties of a Senator,

and may he deprived of a seat in the Senate, al

though he may have done no act of which a court

could take cognizance.” 1 Hind’s Precedents,

§§ 481-483.

This situation is analogous to the Georgia Constitution.

There is nothing in it which limits qualifications of a legis

lator to those expressed therein. In point of fact there

is at least one disqualification in the Georgia law which

is not contained in the Constitution. Ga. Code, § 89-101,

<§, 5, provides:

“ The following persons are held and deemed

ineligible to hold any civil office, and the existence

of any of the following states of facts shall be a suf

ficient reason for vacating any office held by such

person, but the acts of such person, while holding a

commission, shall be valid as the acts of an officer

de facto, vis.:

# * #

“ Persons of unsound mind, and those who, from

advanced age or bodily infirmity, are unfit to dis

charge the duties of the office to which they are chosen

or appointed.”

The qualifications and disqualifications of legislators in

the Georgia Constitution are not all inclusive. In sum, we

find nothing that would compel the House to seat a member

if a reasonable basis, within the context of due process of

law as we shall next discuss, exists for the denial.

Having assumed jurisdiction, we come then to the main

question of whether Mr. Bond was improperly denied his

seat, but this question is prefaced by the test to be applied.

With respect to the test, we hold that the free speech issue

should be resolved in the context of giving effect to the

35

Appendix B—Opinions Below

separation of powers principle, and also our system of

federalism to the extent that it permits self-government to

the states under the supremacy of the Federal Constitution.

There is some authority for such an approach. On the

federal level we have some guidance in the case of Barry

v. United States, 1929, 279 U. S. 597, 49 S. Ct. 452, 73 L.

Ed. 867. That case arose out of the refusal to seat Senator

Vare because of alleged corruption in his election. The

issue was over whether the District Court could grant

relief to a witness who had been arrested by the Senate

because he refused to testify at the subsequent inquiry. The

Supreme Court pointed out that the Senate was acting

within its constitutional powers which were judicial in

character and refused relief. It was said:

“ Here the question under consideration concerns

the exercise by the Senate of an indubitable power;

and if judicial interference can be successfully in

voked it can only be upon a clear showing of such

arbitrary and improvident use of the power as will

constitute a denial of due process of law. That con

dition we are unable to find in the present case.”

On the State level, with respect to state elections and

thus giving effect to federalism but in no wray involving

the separation of powers principle, we begin with Wilson

v. North Carolina, 1898, 169 TJ. S 586, 18 S. Ct. 435, 42

L. Ed. 865. There the governor suspended a railroad com

missioner and refused him a hearing. The Supreme Court

refused relief. In Snowden v. Hughes, 1944, 321 IT. S. 1,

64 S. Ct. 397, 88 L. Ed. 497, a candidate for the state senate

alleged that the State Primary Canvassing Board denied

him his rights under the equal protection clause by a will

ful, malicious and arbitrary refusal through a conspiracy

to correctly certify the results of a primary election thereby

eliminating him as a candidate. He brought his suit in the

District Court under the Civil Bights Act of 1871. The

36

Appendix B—Opinions Below

Supreme Court refused relief on the ground that Ms case

did not rise to the level of invidious, purposeful discrimina

tion cognizable under the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment. The applicable rule of the case is

to be found in the dissenting opinion of Mr. Justice Douglas,

as follows:

“ My disagreement with the majority of the Court

is on a narrow ground. I agree that the equal protec

tion clause of the Fourteenth Amendment should not

be distorted to make the federal courts the supervisor

of the state elections. That would place the federal

judiciary in a position ‘to supervise and review the

political administration of a state government by

its own officials and through its own courts’ (Wilson

v. North Carolina, 169 U. S. 586, 596, 42 L. ed. 865,

871, 18 S. Ct. 435) — matters on which each State

has the final say. I also agree that a candidate for

public office is not denied the equal protection of the

law in the constitutional sense merely because he is

the victim of unlawful administration of a state elec

tion law. I believe, as the opinion of the Court in

dicates, that a denial of equal protection of the laws

requires an invidious, purposeful discrimination. But

I depart from the majority when it denies Snowden

the opportunity of showing that he was in fact the

victim of such discriminatory action. His complaint

seems to me to be adequate to raise the issue. He

chagers a conspiracy to willfully, maliciously and

arbitrarily refuse to designate him as one of the

nominees of the Republican party, that such action

was an ‘unequal’ administration of the Illinois law

and a denial to him of the equal protection of the

laws, and that the conspiracy had that purpose . . . ”

Snowden v. Hughes, as well as Baker v. Carr, supra,

at least teach that there must be a showing of invidious,

37

Appendix B—Opinions Below

purposeful discrimination to give rise to relief under the

equal protection clause. Here we have the due process

clause and First Amendment rights. We think these cases

show that some restraint is to he practiced by the courts in

considering state political questions concerning particular

offices as distinguished from whole systems such as are

prevalent in malapportionment, or racial discrimination. If

this premise be correct, then there is room for a balance

between the separation of powers principle, a system of

federalism and individual rights afforded under the federal

Constitution.

Being of this view, we conclude that a reasonable test

under circumstances such as are presented in this case

would be to assume jurisdiction for the purpose of deter

mining whether Mr. Bond was denied due process of law,

either procedural or substantive. Notice, an opportunity to

be heard, to be represented by counsel, to testify and to offer

evidence and to cross-examine adverse witnesses are en

visioned in procedural due process. The transcript of the

hearing which was held on the challenge to Mr. Bond de

monstrates no absence of due process. It is true that there

was no subpoena power but no request for an absent wit

ness was made. We reject the contention that procedural or

substantive due process was violated by allowing the chal

lengers to vote. A holding to the contrary would do violence

to the power to judge qualifications.

As to substantive due process, we conclude that there

must be a rational evidentiary basis for the ruling of the

House to deny Mr. Bond his seat. The act must not have

been arbitrary.

Does the action rest on any evidence which would sup

port the denial? Thompson v. Louisville, 1960, 362 U. S.

199, 80 S. Ct. 624, 4 L. Ed. 2d 654; Garner v. Louisiana,

1961, 368 U. S. 157, 82 8. Ct, 248, 7 L. Ed. 2d 207.

Mr. Bond’s right to speak and to dissent as a private

citizen is subject to the limitation that he sought to as-

38