Memorandum in Opposition to Stay Applications

Working File

January 1, 1972

26 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Memorandum in Opposition to Stay Applications, 1972. c9579d87-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3e5e3c35-6252-4478-b7f1-7bd4b4ab3970/memorandum-in-opposition-to-stay-applications. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

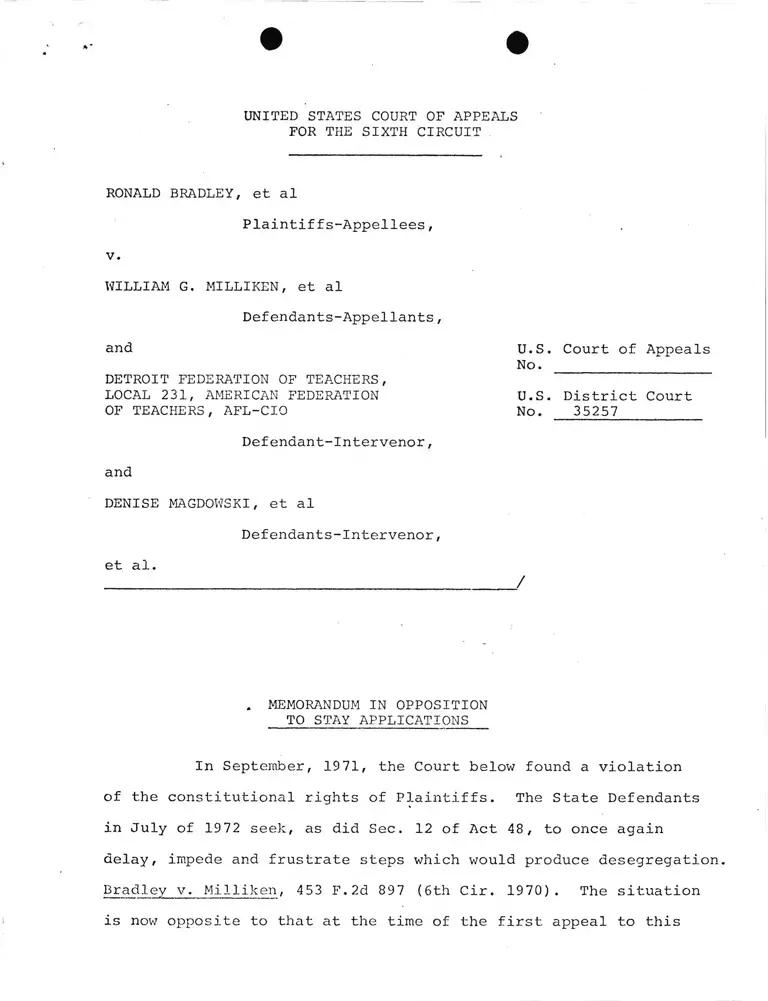

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

RONALD BRADLEY, et al

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al

Defendants-Appellants,

and

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO

Defendant-Intervenor,

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al

Defendants-Intervenor,

et al.

U.S. Court of Appeals

No.

U.S. District Court

No. 35257

/

. MEMORANDUM IN OPPOSITION

TO STAY APPLICATIONS

In September, 1971, the Court below found a violation

of the constitutional rights of Plaintiffs. The State Defendants

in July of 1972 seek, as did Sec. 12 of Act 48, to once again

delay, impede and frustrate steps which would produce desegregation

Bradley v. Milliken, 453 F.2d 897 (6th Cir. 1970). The situation

is now opposite to that at the time of the first appeal to this

Court in 1970: Then, at page 23 of their brief, State Defendants

acknowledged the body of law with respect to delay in desegration

—cases, citing Green and Alexander, distinguishing the case at that

time by reference to the first District Court opinion where the

Court noted that it had made no finding of segregation. However,

the Court, as of September 1971, has found state-imposed segre

gation.

The State Defendants are before this Court seeking a

stay while at the same time opposing the Detroit Board's motion

for an expedited appeal. What they seek in reality is to maintain

segregation. The line of resistance from Sec. 12 of Act 48 to

this date remains unbroken. The granting of a stay now becomes

in effect insofar as Plaintiffs' constitutional rights for

the 1972-73 school year are concerned a determination on the merits

by this Court, without the record, the exhibits, or the two-year,

patient, exploration of the facts and the law by the District Court.

Constitutional rights are present rights and must be given present

effect, Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526, 532-533 (1963);

Carter v. West Feliciano Parish School Board, 396 U.S. 226 (1969),

290 (1970).

The application of State Defendants to this Court

illustrates the difficulty of granting a stay based upon moving

-2-

papers. The issue which is presented is whether the Defendants'

self-serving, and in this case mis-statements, of both the record

and what is likely to happen before an appeal could be heard can

or should outweigh the express findings of the District Judge.

See Swann v. Charlotte v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Bd. of Education,

402 U.S. 1,28(1971); Wright v. Council of City of Emporia,

U.S. ______ (June 22, 1972) slip. op. at 14-15, 19; Brown II, 349

U.S. 294, 299 (1955).

The District Court's order does not contemplate the merger

of any school district in September, 1972. It does not reassign

780,000 pupils. The panel at this time, as the Defendants well know

1. There are several procedural defects which Plaintiffs do

not intend to v/aive but which they do not wish to urge as a

complete bar to this Court's consideration. They include:

(1) The June 14, 1972 order of the District Court is not an

appealable order. However, several defendants, apparently

conceding that a serious question does exist, have pending before

the District Court Rule 54(b) motions seeking to have the

court make a determination under that rule and make otherwise

non-appealable orders, final. Plaintiffs have filed a memorandum

with the court below supporting those motions in the belief

that they are well taken and the pending appeals would be

legitimized and thereby permit expidited consideration by this

Court. (2) The moving State Defendants have deliberately

bypassed the District Court and seek a stay in this Court

on a basis of Sec. 803 of the Higher Education Act. This

act was signed into law before the argument on the motion to

stay the June 14, 1972 order. Despite nationwide publicity

the attorney general filed no supplemental memo and at oral

argument made no mention of that statute. One of the effects

of that choice is to avoid the factual determination which

could have been made by the court familiar with the facts which

might well determine the applicability of Sec. 803 of the

Act to this case.

3

does not expect to recommend to the District Court more than 4

or 5 clusters, grades 1-6 for 1972 implementation. The District

Court's order does not adopt a new school construction standard

but does require the Defendants to follow the standards established

by the State Board of Education and the Michigan Civil Rights

Commission in 1966 pending further orders of the Court. The

faculty reassignments under the order await recommendations by

the panel and the State Superintendent of Schools. In any

event many reassignments would automatically occur as a result

pairings of schools. See Findings of Fact & Conclusions

of Law in Support of Ruling on Desegregation Area and Develop

ment of Plan, Finding 54 at p. 20. The District Court refers

to the "State" and the "State of Michigan" in its rulings, as

does every court when referring to state action whether it be

Brown v. Board of Education or Gideon y, Wainwriqht. Such

reference does not make out an 11th Amendment issue. The

District Court does not hold any statute unconstitutional, but

rather requires the Defendants to act affirmatively to carry

out pupil and faculty reassignment in order to begin the

elimination of state-imposed segregation. See Brown v. Board

of Education 349 u.S. 294, 300-301 (1955). The District Court

in devising relief must shape that relief in accordance with

the factual circumstances existing at this time. See, e.g.,

United States v. Aluminum Co. of America, 91 F.Supp. 333, 339

(S.D.N.Y. 1950); United States v. Union P.R. Co., 226 U.S. 470,

-4-

477(1913); United States v. Dupont deNemours & Co., 366 U.S.

316, 331-32 (1961); Davis v. Board of School Commissioners

- of Mobile, 402 U.S. 33, 37 (1971); cf. United States v. Board of

• 2School Commissioners of Indianapolis, 332 F.Supp. 655 (S.D. Ind. 1971).

2. The Defendants place much reliance on a very weak reed, i.e.

the 4th Circuit's reversal in Bradley v. School Board of the

City of Richmond, ______F.2d ______ (1972). In the first instance,

the principal legal theory relied upon by the 4th Circuit in that

reversal was precisely that relied upon by the same majority in

two cases recently reversed by the Supreme Court. Wright v.

Council of the City of Emporia, ______U.S. ______, 4 04.5. L. W. 48 0 6 ,

June 22, 1972 and, United States v. Scotland Neck Board of

Education, 40 U.S.L.W. 4817, June 22, 1972. Justice Stewart in

Emporia said:

This "dominate purpose" test finds no

precedent in our decisions. It is true that

where an action by school authorities is motivated

by a demonstrated discriminatory purpose, the

existence of that purpose may add to the discri

minatory effect of the action by intensifying the

stigma of implied racial inferiority....The

mandate of Brown II was to desegregate schools,

and we have said that "[t]he measure of any

desegregation plan is its effectiveness."

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners, 402 U.S.

33, 37. Thus, we have focused upon the effect--

not the purpose or motivation--of a school board's

action in determining whether it is permissible

method of dismantling a dual system. The existence

of permissible purpose cannot sustain an action

that has an impermissible effect.

In Richmond the Court of Appeals made "new" findings contrary

to those of the District Court that desegregation was already

complete at the time the District Court issued its ruling re

quiring further desegregation. The Court of Appeals characterized

this as seeking "racial balance" and reversed. Whatever the

merits of the Court of Appeals opinion, it cannot be said that

desegregation has already taken place in Detroit. The Court

below is faced with the task of fashioning a remedy for the

first time where it has found segregation. In that context

its application of the Swann and Davis standards is entirely

appropriate. ■

-5

The District Court has not ordered racial balance. It

has, as Swann permits, established bench marks and goals.

It would be difficult to find an order more faithful

to the Court's rulings in Swann or Davis. In paragraph 11B, the

Court said:

"B. Within the limitations of reasonable travel

time and distance factors, pupil reassignments shall

be effected within the clusters described in Exhibit

P.M.12 so as to achieve the greatest degree of actual

desegregation to the end that, upon implementation,

no school, grade or classroom be substantially dis

proportionate to the overall pupil racial composition.

3. Interestingly, the Emergency School Aid Act contains several

definitions worthy of note in response to the positions taken by

several of the Defendants. Sec. 720 provides in paragraph six:

(6) For the purpose of Section 706 (a) (2) and Section 709 (a) (1) ,

the term "integrated school" means a school with an enrollment in

which a substantial proportion of the children are from educationally

advantaged backgrounds, in which the proportion of minority group

children is at least 50 per centum of the proportion of minority

group children enrolled in all schools of the local educational

agencies within the Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area, and

which has a faculty and administrative staff with substantial

representation of minority group persons, (emphasis added).

Paragraph (7) uses the standard for defining an integrated school ̂

as one which has a racial enrollment " which will achieve stability

and a faculty representative of the minority group and non-minority

group population 'bf the larger community in which it is located...

(emphasis added).

-6-

Order, June 14, 1972). Compare Davis v. Board of School Commis

sioners of Mobile County, 402 U.S. 33 (1971). Several District

Courts and Courts of Appeal have gone further and have explicitly

prohibited the operation of schools above or below a specific

percentage of black— where such enrollments would be substantially

disproportionate to the overall student ratio. See Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education, No. 71-1811 (4th

Cir., Feb. 16, 1972) aff'g, 328 F. Supp. 1346 (W.D.N.C. 1971);

Kelly v. Guinn, No. 71-2332 (9th Cir. Feb. 22, 1972); cf. Yarbrough v .

Hulbert-West Memphis School Dist. No. 71-1524 (8th Cir. March 27,

1972). ;

We would respectfully suggest at this point that the

Court turn to Appendix 2 which is the detailed findings of fact

and conclusions of law issued by the Court below with its June 14,

41972 order. With regret we conclude that the failure of the

State Defendants to include it in their appendix while including

only the relatively brief Order was entirely deliberate. The

record of their willful failure to assist the court below and the

careful exposition of the Court's reasoning and findings would

do much to refute the rhetoric of these Defendants.

4. In particular p.2, (the objective was "to achieve the greatest

possible degree of actual desegregation, taking into account the

practicalities of the situation."); beginning with page 4, para

graphs 6, 7, 9, 11, 13, 17, 22, 27, 32, 41, 44, 50, 55, (faculty)

56, 61, 65, 66 (Swann and housing evidence)/67, 70 (refusing to

decide between competing "governance" proposals)r 72--79, 80 (de

clining to merge districts at this time), 81 (requesting once again

recommendations from state authorities) and 83.

-7

PROPRIETY OF REQUIRING STATE DEFENDANTS TO

PROVIDE FUNDS FOR PURCHASE OF TRANSPORTATION

EQUIPMENT AND RELIEF EXTENDING BEYOND THE

GEOGRAPHIC LIMITS OF THE DETROIT SCHOOL DISTRICT

The Ruling on Issue of Segregation, Ruling on Pro

priety of Considering a Metropolitan Remedy to Accomplish

Desegregation of the Public Schools of the City of Detroit, .

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law on Detroit-only PIans

of Desegregation, and Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

in Support of Ruling on Desegregation Area and Development

of Plan set forth in detail the factual foundation and legal

bases for the District Court's determination to order State

Defendants to pay for the acquisition of any necessary trans

portation equipment and to go beyond the geographic limits

of the City of Detroit to achieve prompt and maximum actual

desegregation, taking into account the practicalities of the

situation. We will here only highlight these rulings.

Under the Constitution of the United States, the

State is ultimately responsible for public education and securing

to Plaintiff school children the equal protection of the laws.

As noted, for example, by Judges Wisdon and Wright in Hall v.

St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F.Supp. 649, 658 (E.D.LA. 1961),

"The equal protection clause speaks to the State.

The United States Constitution recognizes no governing

-8-

unit except the federal government and the State.

A contrary position would allow the State to evade

its constitutional responsibility by carve-outs of

small units."

Accord, Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 16-17 (1958); Haney v.

County Board of Education, 410 F.2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969); Fourteenth

Amendment, United States Constitution. Under the Constitution

and Laws of Michigan, as well, the responsibility for providing

educational opportunity is ultimately that of the State, and

leadership and general supervision over all public education is

vested in the State Board of Education, Art. VIII, 1-3, Michigan

Constitution of 1963. (The extensive duties of the State Board

and State Superintendent of Public Instruction are summarized in

Conclusion 13, pp. 25 and 26, Ruling on Issue of Segregation).

Yet State Defendants, and intervening school districts,

attempt to use this independent state law ground for ultimate

state responsibility somehow magically to insulate themselves, as

subordinate instrumentalities of the state limited by state law,

5from taking steps necessary to remedy the constitutional viola

tions found. Such sophistry has had no foundation in constitutional

adjudication since at least Ex Parte Young, j-k’V 7(S. . ?-~3 .

Defendants have consistently mistaken the application of the

Fourteenth and Eleventh Amendments and the Supremacy Clause to

the responsibility of state administrative and executive officials

at all levels of government; at a minimum, when they are parties

to a litigation, theymust obey the commands of the Constitution,

5. These steps includo£>ayraent for buses and exchange of

pupils, teachers, and equipment incident to the restructuring of

schools to accomplish desegregation.

-9-

as interpreted by judicial decrees enjoining them. Wherqas here,

a pattern and practice of constitutional violation is established,

6

6. Inferentially, this raises the issue whether this Court

should consider the Writs of Prohibition and/or Mandamus ' filed by

three school districts which are within the desegregation area but

are not yet technically parties to this litigation. At the outset,

we note two procedural defects which are dispositive of their petitions.

First, the Writ of Prohibition and/or Mandamus is really a procedure

for seeking appellate review which is available in certain extra

ordinary circumstances,available when no other avenue of appeal is

available. The three petitioners here, however, have a fully

adequate avenue of appeal: under Rule 24, F.R.Civ.P., they may

intervene below for purposes of appeal. See Robinson v. Shelby

County, 339 F.Supp. 837(W.D.Tenn. 1971); U.S. v. Tulsa Bd. of Educ.,

F.2d_____(10th Cir., 1971); Moore's. Federal Practice, S 24:13

/l/ By so doing, petitioners will be able by normal procedures to

secure the review they now seek by an extraordinary procedure. Second,

as a practical matter, they seek review of matters which will not have

any great effect on their material interests in the near term: they

have been asked to provide only planning assistance and the panel

has omitted these districts from its recommendations for inclusion in

an interim plan of pupil desegregation for Fall, 1972.

Eventually, however, the issue may arise whether, and in

what sense, petitioners are now, or may be, bound by present or

future orders of the Court. At a minimum, state defendants can be

ordered to take all actions upon these petitioners necessary to

insure their compliance. U.S. v. T.E.A. F.2d_____(5th Cir. 1972),

stay denied, per J. Black, Edgar v. U.S.,' 404 U.S. 1206(1971), cert

den., 30 L.Ed.2d 663(1971). Thereafter, if the sanctions enforced

by the State Defendants upon the orders of the Court prove insufficient,

the non-party school districts may be immediately joined in the

interests of justice where necessary to accomplish relief. Rule 21,

F.R.Civ.P.

Moreover, it is interesting to note that petitioners raise

no issues not raised by their responsible "parent" state defendants

and by intervening school districts. The reason is obvious: their

legal interests, as argued to this Court, are identical -- they seek

to avoid desegregation. These petitioners are, like all local school

districts, subordinate governmental instrumentalities within the

state-wide system of public education and agents of the state; for

purposes of Rule 65/d) petitioners school districts may already be

bound as "agents /of the parties to the action/ and . . . persons in

in active concert or participation with them who /have/ receive/d/

actual notice of the order. . ." Rule 65(d), F.R.Civ.P. Finally, the

vast majority of school districts in the desegregation area are already

parties to this action. By following the procedural requirements of

Rule 23, the non-party districts may be bound by the proper certification

of a defendant class including all school districts. Cf. Kelly v. Nash

ville Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ., ___F. 2d___(6th Cir, May 30, T5"72)

-ie-

the affirmative obligation under the Fourteenth Amendment is

imposed on all state actors, be they governors, state superintendents

or local officials; and this is so regardless of what particular

person or office first caused the violation. Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U.S. 1(1958); Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County,

337 U.S. 218(1953); Godwin v. Johnston County Board of Education, 301

F.Supp. 1337; Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 267 F.Supp. 458(M.D.Ala)

aff1d sub nom Wallace v. U.S., 389 U.S. 315; Franklin v. Quitmar County

Board, 288 F.Supp. 509; Smith v. North Carolina State Board of Education

7___F.2d___ No. 15,072 (4th Cir. June 14, 1971).

752

See also Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Ed., 231 F. Supp. 743,

"the evidence in the case reflected that the Macon County

School Board and the individual members thereof, and the

Macon County Superintendent of Education, have throughout

this troublesome litigation fully and completely

attempted to discharge their obligations as public

officials and their oaths of office. It is no answer how

ever that these Macon County officials may have been

blameless with respect to the situation that has been

created in the school system in Macon County, Alabama.

The Fourteenth Amendment and the prior orders of this"

Court were directed aqainst actions of the State of

Alabama, The Fourteenth Amendment and the orior orders

of this Court were directed against actions of the State

of Alabama; not only the action of County school officia'ls,

but the actions of all other officials whose conduct bears

on this case is state action. In this connection see

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 78 S.Ct. 1401, 3L.Ed. 2d 5,

1958, where the Supreme Court of the United States, among

other things, discussed the contention advanced by the

Little Rock, Arkansas school officials that they were

to be excused from carrying out the prior orders of the

Court by reason of conditions and tensions and disorder

caused by the actions of the governor and the state

legislature."

-11-

Similarly, this Court has, in an earlier interlocutory

appeal in this cause, reversed the lower court's dismissal of the

Defendants Governor and Attorney General pending a full hearing on

the merits. Bradley v. Milliken, 433 F.2d 897(1971). '

. The Eighth Circuit applied the rule in reversing the

failure of the lower court to devise an appropriate form of 8

consolidation of school districts to accomplish desegregation

without limitations to state law:

Appellees' assertion that the District Court for

the District of Arkansas is bound to adhere to

Arkansas law, unless the state law violates some

provision of the Constitution, is not constitutionally

sound where the operation of the state law in

question fails to provide the constitutional guarantee

of a non-racial unitary school system. The remedial

power of the federal courts under the Fourteenth

amendment is not limited by state law.

Haney v. County Board of Education of Sevier County, 429 F.2d 364,

368(8th Cir. 1970). Accord Griffin v. Prince Edward County, 377

U.S. 218 (1964); North Carolina Board of Education v. Swary, 402 U.S.

43(1971); Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education, No. 29886

(5th Cir. July 1971); J.S. v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

8. As noted, supra, no such consolidation remedy has been yet

ordered in this cause, is not contemplated for the fall and will not

be ordered unless it proves necessary to accomplish desegregation.

As of July 14, 1972 the panel decided "not to recommend consolida

tion or any other change in the present structure of the 53 school

systems in the plan." Detroit Free Press, p. 1, Saturday, July 15,

1972. See Ruling on Propriety of Considering a Metropolitan Remedy

to Accomplish Desegregation of the Public Schools of the City of

Detroit, at 3; and Findings of Facts and Conclusions of Lav; in Support

of Ruling on Desegregation Area at 24-27; Ruling on Desegregation area

and Order for Development of Plan of Desegregation at 8-9.

-12

District 406 F.2d 1086, 1094(5th Cir. 1969) and Adkins v. School

Board of Newport News, 148 F.Supp. 430, 446-7(E.D .Va. 1957), aff'd

246 F.2d 325, cert. den. 355 U.S. 855(1957).

In fact, that very proposition was enunciated by the

Supreme Court in Brown II when it recognized that single judge

district courts in remedying state-imposed school segregation "may

consider problems related to administration, arising from the

physical condition of the school plant, the school transportation- g

systems, personnel, revision of school districts and attendance

areas into compact units to achieve a system of determining ad

mission to the public schools on a non-racial basis, and revision

of local laws and regulations which may be necessary in solving the

foregoing problems." 349 U.S. 294, 300-301(1955). See Ruling on

Propriety of Considering a Metropolitan Remedy to Accomplish

Desegregation of the Public Schools of the City of Detroit at p. 3.

9. Whatever the meaning of a memorandum affirmance of a three

judge court by the Supreme Court, State Defendants' citation of

Spencer v. Kugler is as inapplicable to the factual situation of

this case in this Court as it was below. In Spencer plaintiffs

sought to declare invalid a New Jersey law making school district

lines coterminus with municipality lines upon a showing of mere

racial imbalance, without making any allegations that discrimina

tory "state action" in any form, in any place, at any governmental

level contributed to such segregation. The 3-Judge District Court

dismissed the complaint. 326 F. Supp. 1235(D.N.J. 1971),

aff'd mem., 404 U.S. (1972). .The complaint in this case is

totally oposite that in Spencer. Discriminatory State action was

alleged, proved and found in overwhelming detail; since that

finding the District Court has conducted lengthy hearings, and

ordered that preparatory steps be taken to the end

that an effective remedy for the state-imposed segregation could

be accomplished.

-13-

In Board of Education v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43, 45(1971)

the Court said:

"/S/tate policy must give way when it operates to

hinder vindication of federal constitutional guaran

tees . " '

And in Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 575(1964) the

Supreme Court said:

" Political subdivisions of States--Counties,

Cities, or whatever— never were and never have been

considered as sovereign entities. Rather they have

been traditionally regarded as subordinate governmental

instrumentalities created by the State to assist in

the carrying out of state-governmental functions."

Again in Haney, supra, "Political subdivisions of the State are

mere lines of convenience for exercising divided governmental

responsibilities. They cannot serve to deny federal rights."

See also Jenkins v. Township of Morris School District, 279 F2d

617, 628 (S.Ct.N.J. 1971); Lee v. Macon County Board of Education,

448 F.2d 746, 752 (5th Cir. 1971); United States v. State of Texas,

447 F.2d 441, 443-44(5th Cir. 1971) affirming orders reported at

321 F.Supp. 1043 and 330 F.Supp. 235.

The only "massive" thing in this case is the magnitude and

scope of the constitutional violation found by the Court below and

the substantial evidence introduced in support thereof. In its

Ruling on Segregation (see Appendix Fj ) , the District Court

summarized the causes of segregation in the Detroit public schools,

including the substantial contribution by state and local defendants,

and other state actions contributing to such segregation. (We have

-14-

attached as App. C the Proposed findings submitted by plaintiffs

which,except for faculty findings,were adopted and summarized by

the District Court in his September 29, 1971 Ruling on Issue of

Segregation.) In its Findings of Facts and Conclusions'of Law

on Detroit-Only Plans of Desegregation, the District Court found

that any plan of desegregation limited to the Detroit public

schools would be less effective than other available alternatives.

10

In view of the "practicalities of the situation," the Court was

forced by the record to contend with the historical pattern of

school segregation, containment of blacks in separate schools,

and racial separation throughout Metropolitan Detroit which

resulted from the interaction of school construction, site

selection, plant utilization, and student assignment practices

and housing discrimination and segregation effected by discrimina

tory action at all levels within and without the Detroit School

District. See, e.g. , Ruling on Issue of Segregation at ?\vpO. h

and Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law in Support of Ruling

10. And in reviewing factual determination in this regard,

ppellate ourts must, even upon a full review on the merits, rely

primarily on the decisions of the District Judge. Wright v.

Emporia, slip op at 14; Brown II, 349 U.S. at 299. This can only

be more true on a stay application, where moving parties bear a

particularly heavy burden.

-15-

11

on Desegregation Area and Development of Plan at ^

11. "65. In our Ruling on Issue of Segregation, pp. 8-10, this

court found that the residential segregation throughout the larger

metropolitan area is substantial, pervasive and of long standing and

that governmental actions and inaction at all levels, Federal, State

and local, have combined vzith those of private organizations, such

as loaning institutions and real estate associations and brokerage

firms, to establish and to maintain the pattern of

dential segregation through the Detroit metropolitan area. We also

noted that this deliberate setting of residential patterns had a-n

important effect not only on the racial composition of inner-city

schools but the entire School District of the City of Detroit.

(Ruling on Issue of Segregation at 3-10) Just as evident is the fact

that suburban school districts in the main contain virtually all-white

schools. The white population of the city declined and in the

suburbs grew} the black population in the city grew, and largely, was

contained therein by force of public and private racial discrimina

tion at all levels.

66. We also noted the important interaction of school and

residential segregation: "Just as there is an interaction between

residential patterns and the racial composition of the schools, so

there is a corresponding effect on the residential pattern by the

racial composition of schools." Ruling on Issue of Segregation at 10.

Cf. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg, 402 U.S. 1, 20-21(1971); "People

gravitate toward school facilities, just as schools are located in

response to the needs of people. The location of schools may thus

influence the patterns of residential development of a metropolitan

area and have important impact on composition of inner city

neighborhoods."

67. Within the context of the segregatory housing market, it

is obvious that the white families who left the city schools would

not be as likely to leave in the absence of schools, not to

mention white schools, to attract, or at least serve, their children.

Immigrating families were affected in their school and housing choices

in a similar manner. Between 1950 and 1969 in the tri-county area,

approximately 13,900 "regular classrooms," capable of serving and

attracting over 400,000 pupils, were added in school districts which

were less than 2% black in their pupil racial composition in the

1970-71 school year. (P.M. 14; P.M. 15)

68. The precise effect of this massive school construction on

the racial composition of Detroit- area public schools cannot be

measured. It is clear, however, that the effect has been substantial.

Unfortunately, the State, despite its awareness of the important

impact of school construction and announced policy to control it,

acted "in keeping generally, with the discriminatory practices

which advanced or perpetuated racial segregation in these schools."

Ruling on Issue of Segregation at 15; see also id., at 13."

resi-

-16-

Although defendants argue that such "housing proof" is

inadmissible, the Supreme Court expressly authorized District

Courts to consider this proof - it constitutes the "loaded game

board" which renders the desegregation process more difficult than

it might have been in 1954 ". . . by changes . . . in the structure

and patterns of communities, the growth of student population, move

ment of families, and other changes, some of which had a marked ■

impact on school planning . . ." Swann, 39 U.S.L.W. 4431, 4441 .

The construction of new schools and the closing

of old ones is one of the most important functions of

local school authorities and also one of the most com

plex. They must decide questions of location and capacity

in light of population growth, finances, land values,

11

11. The record below, summarized by the District Court, shows the

deep involvement of both the Detroit and State school authorities

in establishing and reinforcing patterns of housing and school

segregation. See the detailed analysis in App. . Moreover th-

record, without housing evidence, clearly supports the finding

of action and inaction on the part of all defendants which

constituted the causal factors in the school segregation. Indeed,

the vast majority of the trial below concerned matters Ouher than

housing proof. However, as the Courts have noted, the proof of

housing segregation is often introduced by plaintiffs for the

precise prupose of showing the role of school authorities. ^Other

wise housing segregation is the school authorities' first line of

defense to a charge of school segregation. It matters not

whether the city is North or South, East or West.

12. Cf. Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, ___ U.S. ___, slip

op at 11, 13.

-17-

site availability, through an almost endless list of factors to

be considered. The result of this will be a decision which,

when combined with one technique or another of student assign

ment, will determine the racial composition of the student body

in each school in the system. Over the long run, the conse

quences of the choices will be far reaching. People gravitate

toward school facilities, just as schools are located m

response to the needs of people. The location of schools ma_V

thus influence the patterns of residential development of a_

metropolitan area and have important impact on composition of—

inner city neighborhoods.

In the past, choices in this respect have been used as a

potent weapon for creating or maintaining a state segregated

school system. In addition to the classic pattern of building

schools specifically intended for Negro or white students,

school authorities have sometimes, since Brown, closed schoo s

which appeared likely to become racially mixed through changes

in neighborhood residential patterns. This was sometimes

accompanied by building new schools in the areas of white ̂

suburban expansion farthest from Negro population centers m

order to maintain the separation of the races with a minimum ̂

departure from the formal principles of "neighborhood zoning.

Such a policy does more than simply influence the short-run

composition of the student body of a new school. It may^well ̂

promote segregated residential patterns which, when combined with

"neighborhood zoning," further lock the school system into

the mold of separation of the races. Upon a proper showing^

a district court may consider this in fashioning a remedy.

Swann, Supra (emphasis supplied).

Based upon exactly such evidence, the Court below

determined that Detroit-only plans which attempted actual desegrega

tion would clearly make the entire Detroit Public School System

racially identifiable as Black. It would make a segregated school

system more segregated, with a decreasing white enrollment in the

13. "In ascertaining the existence of legally imposed school

segregation, the existence of a pattern of school construction

and abandonment is thus a factor of great weight." Swann, supra.

-18-

face of a pupil population already almost 70% black; the Court

concluded that Detroit-only plans "would not accomplish desegrega

tion." All surrounded by white schools in suburban areas where

400,000 pupil spaces have been built in the period 1950 through

1969. Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law on Detroit-Only

Plans of Desegregation. In light of these findings and concludions,

the Court below determined that it was proper and required to con

sider, develop, and take all steps necessary to effect a plan of

desegregation for the Detroit Public Schools which would not be

simply a black set of schools in the Detroit community surrounded

by a set of white schools — all stemming from the original determin

ation of a pattern of "state action resulting in segregation."

Stay Applications in School Desegregation Cases

The rule in desegregation cases, North and South, has been

to deny or to vacate stays and issue pendente lite injunctions to see

to it that plans go into effect. See, e.g., Lucy v. Adams, 350

U.S. 1(1955); Keyes v. School District Number One, 396 U.S. 1215

(1969)(Denver); Guey Heung Lee v. Johnson, 404 U.S. 1215(1972)

(San Francisco) . See also Swann v. Charlotte Mecklenberg_Bd_.— of.

Educ., 399 U.S. 926(1970)(granting certiorari and fully reinstating

the District Court's order pending the Supreme Court hearing)

-19-

If a stay is granted, even the limited implementation

set for September of the District Court's order will not be

possible. The injury to plaintiffs will be clearly compounded and

irreparable. There are no reasons which would justify a drastic

departure from the "desegregate now, litigate later" rule of

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Educ. , 396 U.S. 19 (1969) and

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396 U.S. 226(1969).

See Edgar v. United States, 404 U.S. 1206(1971).

Defendants allege that there is "a substantial probability

that the District Court's order of June 14, 1972 will be reversed

on appeal." Grounds for this statement are that the order has gone

"beyond Federal appellate precedents." It comes as no surprise to

plaintiffs that the defendants once again insist they are correct

and the District Court is wrong. In addition to the numerous

authorities cited elsewhere in this memorandum the following cases

are applicable to a consideration of this assertion.

Mr. Justice Black denied a stay in the order in U.S. v.

Texas Education Agency, supra, for statewide relief in United

States v. Edgar State Commissioners of Education, 404 U.S. 1206(1971)

saying:

It would be very difficult for me to suspend the order

of the District Court that in my view, does no more than

endeavor to realize the direction of the Fourteenth Amendment

and the decisions of this Court that racial discrimination in

-20-

the public schools must be eliminated root and branch . . . .

For me, as one Member of this Court, to grant a stay now

would mean inordinate delay and would unjustifiably further

postpone the termination of the dual school system that the

order below was intended to accomplish . . . .

When the case was presented to the full Court the

petition for certiorari was denied. Edgar, State Commissioner of

Education, et al., v. United States, 30 L.E. 2d 663(1972).

On April 3, 1972, the Fourth Circuit in Brewer v. School

Bd. of Norfolk, 456 F.2d 943(4th Cir. 1972)(en banc) issued a stay

pending certiorari of an order directing the Norfolk School Board,

which had not previously operated a pupil transportation system, to

provide free transportation at a projected cost of $3,600,000 to

approximately 24,000 students who were assigned to schools beyond

walking distance under a court-ordered desegregation plan. Norfolk

too urged that its situation was novel. It too questioned the

power 0f the federal court to order a governmental agency to " . . .

levy and collect taxes for the purposes of providing free trans

portation to school students. The questions presented affect the

taxpayers and school boards of every school system in the country in

which free transportation for every student is not now provided.

In metropolitan areas, it will have an enormous impact upon general

public mass transit and automobile traffic problems." (Petition for

certiorari in Brewer v. Norfolk, app. >- 0, ! ) On the motion of the

i

plaintiffs, the Supreme Court vacated the stay and denied the Board's

petition for certiorari on May 15, 1972. 40 U.S.L.W. 3544.

-21-

Stays on Planning and Acquisition of Transportation

As to the June 14 order state defendants seek a stay of a

basic planning order. In this Circuit, pursuant to the commands

of Carter v. West Feliciano Parish School Board, 396 U.S. 290(1970),

such stays must be vacated. Kelley v. Metropolitan Bd. of Ed. of

Nashville, 436 F.2d 856, 862(1970). A stay on planning serves no

purpose except to frustrate any chance of desegregation, even

before a plan is in the record. Rather the minimum duty in the

desegregation process is that "some demonstrable progress be made

now and that a schedule be adopted forthwith in order that a

constitutional plan will be implemented . . . " Acree v. County Bd.

of Ed. of Richmond, Ga., ___F.2d___, no. 72-12111(5th Cir. March 31,

1972) .

In footnote 2 of that opinion, the Fifth Circuit also

noted that the acquisition of necessary transportation equipment is

an integral part of the planning and preparation for eventual

implementation of any interim or final desegregation plan, for

without necessary transportation there can be no implementation.

Thus what defendants here seek is a stay on implementation by the

indirect method of halting those preparatory steps necessary to

implementation. Regardless of the merits of a request for stay of

implementation, planning and acquisition of transportation should

therefore continue.

-22-

And in any event — as the District Court noted at both the

July 11, 1972 hearing, where it directed the acquisition of trans

portation capacity and on Thursday, July 13, 1972 at the ex parte

hearing on the state's second motion for a stay — the equipment

ordered would be needed under a Detroit-only as well as a metropoli-

14

tan plan of desegregation. After pointing out that he had found

de jure segregation in September 1971, the Court said: .

" The renewed motion of the State for an

immediate order is hereby denied for the reason that

any stay in the ordering, the acquisition of and pay

ment for transportation equipment would seriously jeopardize

and certainly delay the Court's duty to desegregate the

public schools of the City of Detroit and because even if

the reviewing court were to conclude that the metropolitan

desegregation order were inappropriate the duty to desegregate

the public schools of the City of Detroit within the City

itself would require the transportation equipment directed to

be acquired and that any desegregation effort, whether metro

politan or city could not be implemented for the beginning of

the school year in the fall of 1972 unless the transportation

equipment is ordered now, meaning today, or certainly within

the next few days." (Transcript, July 13, 1972, p. 7,8)

(See App. 1).

14. The State Defendants' argument that any funds expended for

acquisition will be lost in case the court's metropolitan approach

is reversed is patently false. In addition to the fact that the

buses are needed for a city-only plan, they can be used, in any

event, to assist in the historic expansion of transportation which

is occurring in the State wholly apart from desegregation. There

are some 10,000 school buses presently owned and operated by school

districts in the State of Michigan.

-23-

" . . . where the State, and named defendants, are

substantially implicated in the segregation violation

found and are ultimately responsible for public schooling^

throughout the state, the consistent application of-constitu

tional principles requires that this court take all steps

necessary and essential to require them to desegregate the

Detroit public schools effectively and maintain, now and

hereafter, a racially unified, non-discriminatory system in

the absence of a showing that the judicial intervention here

contemplated will frustrate the promotion of a legitimate and

compelling state policy or interest. Reynolds v. Sims, 377

U.S. 533, 575(1964); Hunter v. City of Pittsburg, 207 U.S.

161, 178-179(1907); Phoenix v. Kolodziejski, 399 U.S. 204,

212-213(1970); Kramer v. Union Free School District, 395 U.S.

621, 633(1969); Williams v. Illinois, 399 U.S. 235, 244-45

(1970); Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479, 488(1966); Green v.

County School Bd. 391 U.S. 430, 439, 442; Swann v. Charlotte-

Meckienberg, 402 U.S. 33(1971); Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483(1954); Brown v. Board of Education," 34$ U.S. 292,

300(1955); Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450, 459

(1968) . "

And to accomplish such desegregation, as the district Court below

noted,

As the District Court held^

"Funds must either be raised or reallocated, where

necessary, to remedy the deprivation of plaintiffs' constitu

tional rights and to insure that no such unconstitutional neglect

recurs again. Shapiro v. Thompson, 397 U.S. 254, 265-266(1970);

Boddie v. Connecticut, 91 S.Ct. 780, 788(1971); Griffrn v.

Illinois, 351 U.S. 12(1956); Graham v. Richardson, 403 U.S.

365, 374-375(1971); Mayer v. Chicago, 404 U.S. 189, 197(1971);

Griffin v. Prince Edward Countv, 377 U.S. 218(1964); Hoosier v.

Evans, 314 F.Supp. 316, 320-321(D.St.Croix,.1970); United

States v. School District 151, 301 F.Supp. 201, 232(N.D.111.

1969), aff'd as modified, 432 F.2d 1147(7th Cir. 1970), cert

denied,~402 U.S. 943 (1971); Plaquemines Parish School Board

v. U.S., 415 F.2d 319(5th Cir. 1970); Bradley v. Richmond,

F.Supp. (April 1971); Brewer v. Norfolk, 456 F2d 943

(4th Cir., March 7, 1972)(slip op. at pp. 7-8) cert denied

40 U.S.L.W. 3544. It would be a cruel mockery of constitutional

law if a different rule were to be applied to school desegrega

tion cases. After all schooling is this nation's biggest

industry and the most important task of government left to the

t fhis case, were a differentStates by the Constitution. ̂ ^ Utute a gigantic hypocrisy.

rule to be applied, 1 been spent over the Y relatively

?o” his Court's attention.

to Plaintiffs one overriding consideration

in measuring the harm to Plarntrl

must be given:- _ school children

"It 1h Cling under nondiscJimiLtory and constrtutional Uved

^ n l l S n a g t b e tecaptured - a ^ s c

county Board ox_Educatron,

rrpr the determination of. two vears after rue ^ln that context, tuo y ^ ^ ^ tolerable. There is

constitutional vrolatron, ^ a aesegregated edu-

no harm to defendants for pupa ^ q£ state action in

. There has been m thxs casecation. Ther 12 of Act 48.

1970 “ e f£ S C t “ " ' ^ T f ^ i T o f T l o n g sta n d in g p a t t e r n and

SubSequently there w a ^ segregation the area.

practice of state P without any irreparable

district court's orders wall provrd , begin„i„gn 1 district boundaries or governance, g

changes m sc oo ^ District Judge tool "note

of a remedy for the vio and

• caf White and black students m th of the proportron of white ending white schools

/sought/ as practical a plan .. « ^ schools ^ are

and black schools and substituting -

-25-

representative of the area in which the pupils live." Kelly v.

Metropolitan Board of Ed. of Nashville ,__F.2d.___(6th Cir. May

30, 1972) (Slip op. at 22) .

Defendants have in no measure met the heavy burden on

a moving party necessary to justify a stay. What they should have

done and can still do is accept the District Court's invitation to

take steps under the rules to obtain an appealable order. That

invitation has been accepted by some defendants in the form of

Rule 54(b) motions, which plaintiffs supported below. They could

also join the Detroit Board's request for an expedited appeal and

for leave to appeal on the original papers. Then on the full

record and on briefs of the parties the merits of the case can be

heard.