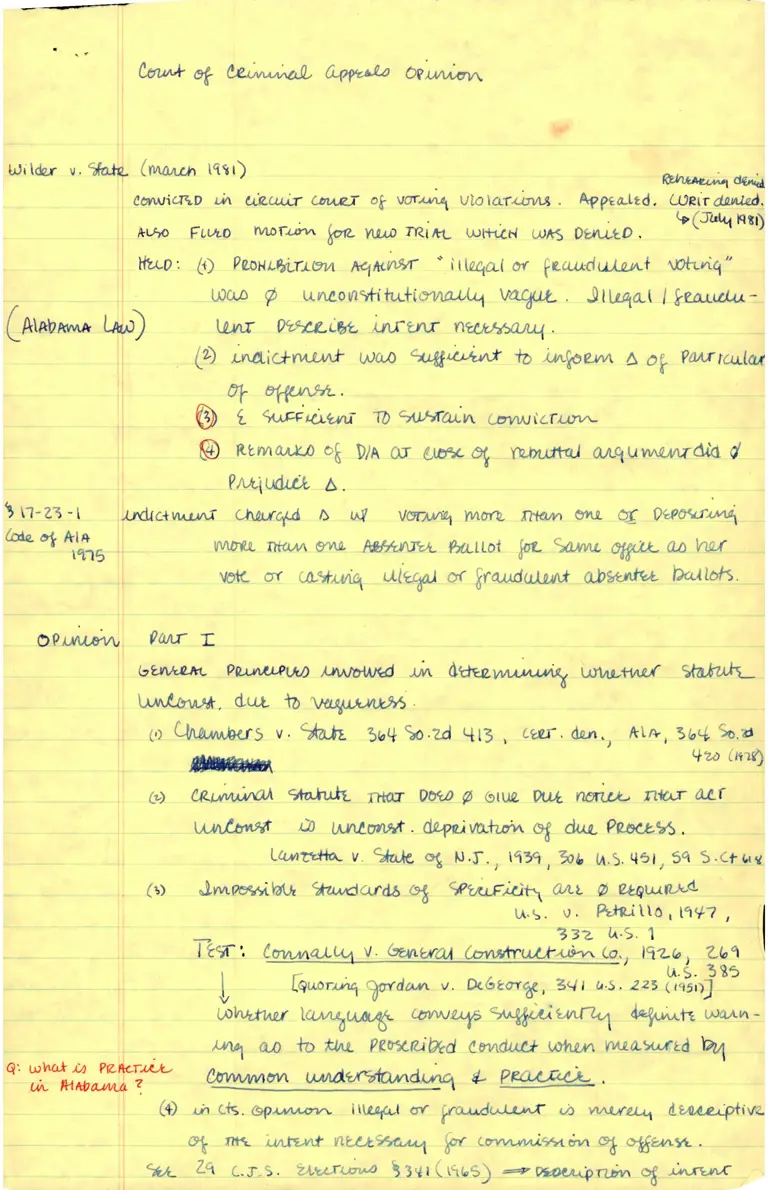

Attorney Notes

Working File

January 1, 1981 - January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Attorney Notes, 1981. 449eb9f4-ef92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3ea285fe-85a9-4fc3-802d-d76a7747078e/attorney-notes. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

Cat* E !fu,^";.'al, A4pzuea Ov'pttq,ow,

trat&, v, Aah- \vrarun tet r)

eav\Nic-T\D u^ c*auir Lw*i ofi voru^\

Ar.io FtwO wwruit, fiot Vvro lRirtl-

(mou*^o r.tr)

t rr- zi -l

(dc- ol kl*

rfl5

vio lcLTtttAA . Ag peuLzd,

tpt+trnt t,ttls OttwtO .

W*1*ailiq db[

Cljerr du^kn.

S(.rr,q ntry

t o, A un4on*i hxlfotM)tq \raC#L, .!ll4al I ts!&,rtu-

\U^f 0?jil-cW tt1tr?J17 n4JurflJq.

e) tvtfuic-rtu-t-p* Wo.o *a,tr+r,* +D ;wc6owy. A of ?arvyu1*

q

L 1u.pe qtqtrtf Ib nJ'rfAxw LEt^Nicf t-ut t-

R,Lrrnad, o& Dln 0r Uru e1 yyhtttd a^q u w'tnrdio d

?,ucy&L*. A.

,t rrdtC+ tl/ur^I U\lLt c,fd A t^I VtrNv\ YnilL nfi/n glt-q. q D*O*t ,r,\

n^r*.e. ntu^ eyv1,.e. M-t+-nlvt huttot w ,t)tw ott^u 0a v1t/,(

v9K cY ,,Ltfu/q UlZcp o{ Vc;udu..llf ObrultL l>r*ttotS.

o? ttttl,vw ?anr T

bLvr*l*r- ?ettlt*t*O M "!i" dAzzrtr*t^rtu, vJluu.;+1^.s{ Z+a,tu}Z

tr,rnbtnrat , dt* Io vuepruuhS

(,) CtMn^bcr5 v, *t"tz 5,o* %.zt ttt3 , c?ar. d.art,) ALrv,

M

Ceutruirgtt <,/r.}uft ftar 0a@ O Orug V,U norit k-, ntur At-f

rrt ttrft*tt A tJu\^C-atwt . dlr?c;rtahA on && ?Qoe.ars ,

Ltuz**o- v. nn^k % N.f. ) t731 ,hb h.S. q5t)5q S.cf r,rr

Jrwreq#,i,latt *a*dcttd^s % <frtru-triil\ a/LL O LtgwLt-bo

tl.t. u. k)t;itlo, 17<1.7,

Z=z {^.S. 1

Ttf ', CW\v.fuwal CotXTu.fmco., lTza) Zb1

t Lruo.* rltrda,n v. D<6tm6, 3q,

^.'

,rr,l.?;r;"t

trchhfl^tr L*ft% @ywu16 -Ar'!dtd 4*p*n Lpa./rr^ -

to tllo- ?(WLiWd Ctudu* tfth-en vve-uv.,,rtd Wl

tuttd+,alandmrt 4- ?eag<!-L

(+> rrn cts . e?^,t^^-or1 it\l4a,t 6t tfc^tuduJJr,q @ v/\!rru-q d.tno*iptivz

% ft1- .u^tax* ttltil.rrcu\ W cvvv-vvrigLcn efi offt^n.

'*rL L\ c.r s . z^"t-Lrurua Bl*r thb5) aweteruil % r*\tu\r

tlt*0, (.0 ?WXrJar-rtou hclttun*r " tttaqcu{ or fru*du]tnl r0ttnq"

@

@

3b+ fu.zr

t*z,o &x)

(r)

(r>

wV(* M ?rzncrut*-

tiL kltfro-uwr 2

ryca

Cwv\/wtov\

q:

Urr^* % A,ppta;Lg O1trt,*rvt-

@ 5z Atq ioz (rtro) L?qB, u iLtv of 9,r q-ru-h nS

Dqr"s,ntun*D bq ,.+Or-tmt c-t: ?ao<tAVL dq?uicak voht\

Witl &lUt Vgp. funr**w\ild void k" vrup*nv*5 ontq pt*

uho* 0r{Q-"tr*e/'^4 '?-xtru*rl- qLuulv8foJvu/U . g1L %.?A 1o( (tqH) @

e)ttuaut+u*tttrt (:t_-.1tttv' 6ortor'" ', ' cu*'l," v' 1ra/ir. , 131 %zd +1 (lloz)

L

"@

canb" w LLw.^rto ) ur,,/t d al y?h%'np*V de{ya*L q

Ct4-+ct^rLh{ hsru 6u* uJho* LW . 'u fu^n*t.

- L^tut r[ nll1p.l^ a^d pr:1tdaJl.llt \awgta,<g ia

r.ohut uuo i5)ewoW.

Ycvntu,nAu % groJnt*t tot c*rfilvtun*

%

A M u$trprutt-utr, pro&ocx*ot to 9 t-r - Z3 - 1 ng TfL}rorusT-

L:'ktt &Erpro-tahiu protti ocd- 4 @ 5z frta.

Lqq ( {glr) , Gcr drln 5z N"L bv ( t<rs)

u\ourww)^f wan O VM,ttur-

, r 5tt Rrqqt*tA v 4 5, Laoa 26 Sc+ tql,

glL r11 U.s.5q-7

6 ?ltr'u*rn % ,ru*ufu\ Ept,LL iN ntr. unrds e1, "lundz wftt-t

[hercfd ^4 ),nd-ic-+tu.onr. 6{u'AtAv.*z,le

-

'tr io.a br (n56)

UUtrr^*ctttO*p,

Wrr{q urolr 0 tutWc+

v w MjevnP^unato ht-l Trlt rctlr' {

Yu\trttvu*A *i,at Accu,Ok-J:a:y| t1, iltzqo-l

Mlswpepnitp hLl fuLr9

6xt ttlc.qcrl Vc+/q/1r-l wVvict', {flifuLd M JrWf *h,t- tlLtctili\

ttyw./att/l. (re. Vsttj/tq vtntre- tJna Onel) tA)lto cnLbLailnf.

(D* U. r,tntuxprets ;fuX*z au.br t14a-t " xll\al ot (ra,uAu-Ut*l " vot-.,-l

lb Re*O wt cwYurslf Lo:rr wl (rnd,gtes) frhf 01( <KarL(L. TWrmmfi

,6+tn\ y\/\ofl- _n*aAL vy\,oL tn j t t tqa,t fl fira,uduletafr .

lvtd*nt t-

dlf'tl TtTl,uvwvt-r,l ok aryr, LM

VA$).L , (A.,w tlJ/4 1yt

Lot/Wil-t ?foqx^Dd,.

b*tau

?*t{-

(D c+. W

\Wrn*

"t}{tq fLtt

tL RoVxttt G"i wtoo p.LWALS uuv,tttV.t%d \lt}Frnl b)C

Itvr,yzo rTfrr4 did A \DtL f<0**** .

ryt.e:ryn1|| @ TuLnltrLdwLh5 of lLv/rvtsl/\ W Tvizr 9t PlJ Ury:_%&'*WCoxitdCL q I

)

fo A"etoL *ito .3r5 'x..zn Z4L ttnlb)

fturr+fucNL% "t wr**rl w/hlb wl.ur x*t*tlttt-qb tDl vrN$D\,w1tktur+vut @3r w?o5.

W rt Uu,r,u^/,^d \qVta,Ls o?)r.yrLbrtuJ

t?tWwtrgw /d\{tn/\tl- ,;rArs (o,rrtr v.tttz Z3s pr1a. 5?3, t6o So laz,

',a^fr*,rn,r*iiiffwrn*ta*v,nr,lt 2. ytuilrr UL *ctoredd fu)tt/u- t^)!*1*rt cA dtrcC-t

(tqrt)L

cL CLtv.. Cv\&. cllfrdr6--' '

tavrvtl;/vsvr. L WtU- V. <*ad1_ 17X 1t,ud 4gt

Patw tV Wnwo racz rltru BE oF t@t. kLvw*pa e ln cloi\ *+clunaa(

fHrlf HL HAO A<l/t(trbl ttt- hgt u)VHL ?^Ol* v1;to,^/\ f i lltd .

A CO,m,rrcf tnntptttti TZIA A W${n RAcifit- LOv v1tlJtvs Ft&.$.

Pnoetr. K?fir+tal kw vondtd +o a Lloxncl a-rclLwnn u'f ,

lwT v , (-ourvto @- rT 4u/1r4 owl?Lttd ro ?4c ,lakd rTtL Cowt.',wfuin^a

' q lriorz urlo lrarliq tntntu*rtb'"rp of a

ry\r,y iy+,r (,ru* ccvt ?xlo; rtur iud{ e4g ?o/"Akd out gWiA fuAdan ot

unnttrtt't*t,,v..-

?Rq . n&-did 'r-t cvwwtrl,N eA nit wn-r of ,ltt t or ,y Ib

l.,ohet had or had O VLtn ?rovd rq44g4a v, Vatt ?g b.?d w1

0az1

M4J^ v, </tufLW) (ma.rr,n- r4$r, L-WLa^/,\ Lvaruizd fr kpqiuqfrt) u:e(r De,vtrLt;61

rtsD v

, Unorl4dt wl *tuvnt 3 tsunf ,+,tnd,i,ctwr-o-ptf oa aritdr.f.

r rr,Wrrorn W v,l^^l ra.'ar- WnILLD glc yto ltlT*rnaua| ot oryu*a,uf 'oaAL.

Lt/l tTtt O.Un+tu COUttl *,Un [L*TtwtyWtt C(^ %nin Gtwwutt ,; . n s.

WoA /Oubg*0r^ri4u4

Aw,vi*, hitl q: , fuaftle Gtnsn v- f]ut Danat Lueit\e l.hrris

Ul&t ITtt- Z)n^o A.o ){t iJJid.ara.o ){t i;Jid.ar .

, ?t(tnet 1tb 0 ?RLh?xfi A ch*,.+ Qo ttwz?ratw rayon m.

,; ,4Wn +4 'UnAk-ut+ otto ,

oPttL^;,,,^ t . 3 n-23-.t tb Gw*itt,*two) ( qqlLd4.r)

9. JW

^,t\d,ic*vu-on*

A vd'tid . ( toi H4r)

rphcrr^r, fv,* Ueettw,6+tuL+ioJ L waD a4gumt to 1a+pott Ytrd)cf.

W WrW. Dorvrh v. %tz ?r Z.?d tlz Lkra rlso)

, \rrr^b v' *zt< 3rre %,d }lt CA'14 C&.APPhIS) Qu.friutD,

1