Northcross v. Memphis City Schools Board of Education Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

September 26, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Northcross v. Memphis City Schools Board of Education Reply Brief for Appellants, 1973. 269c9ad2-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3eac859d-c49e-4949-a019-b4b2b25fd2b3/northcross-v-memphis-city-schools-board-of-education-reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

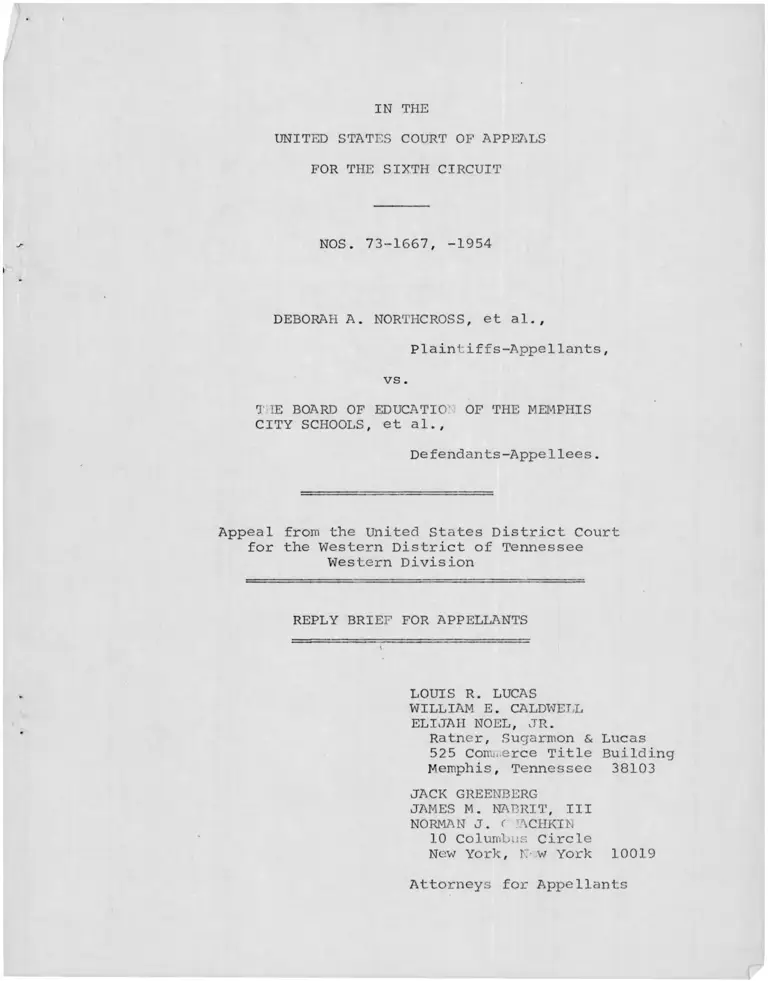

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NOS. 73-1667, -1954

DEBORAH A. NORTHCROSS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

T IE BOARD OF EDUCATIO OF THE MEMPHIS

CITY SCHOOLS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the united States District Court

for the Western District of Tennessee

Western Division

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

LOUIS R. LUCAS

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

ELIJAH NOEL, JR.Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Coirui.erce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. ( ACHKIN 10 Columbus Circle

New York, H- w York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

1/NOS. 73-1667, -1954

DEBORAH A. NORTI1CROSS, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE MEMPHIS

CITY SCHOOLS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Tennessee

Western Division

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

We address, in this Reply Brief, what we read to he

the major thrust of the Memphis school board's written

presentation to the Court: a calculated yet subtle effort to

The appeal in No. 73-1667 is taken from the district

court's May 17, 1973 order approving "Plan II" in principle

subject to the submission and acceptance of detailed satellite

zone descriptions. See Brief for Appellants, p. 7, n. 7.

When the main briefs were prepared, the district court's July

26, 1973 order approving the board-drawn satellite zones had

been entered, and the briefs of both parties make reference to

that order and to the material submitted to the district court

between May 17 and July 26. Plaintiffs noticed an appeal from

the July 26 order to protect the record, and that appeal has

portray this matter as an unimportant dispute, tangential to

the main business of desegregating the Memphis school system

(which the board would congratulate itself for having accom

plished under court order), and which is easily to be resolved

by an unquestioning reliance upon the district court's judgment

2/

\J cont'd

now been docketed as No. 73-1954; by stipulation of the

parties and the order of this Court entered August 20, 1973,

the appeals in Nos. 73-1667 and 73-1954 have been consolidated,

and no independent briefs on the merits in No. 73-1954 are required.

2/ For example, unlike plaintiffs' detailed and specific

statement of the case (Brief for Appellants, pp. 3-18), or

the even more detailed history of the proceedings (id. at

la-14a) since the last remand from this Court, the school

board's brief treats the facts in a cursory and superficial

fashion. This approach distorts the case in several ways:

first, the board can then omit critical facts on a selective

basis. Nowhere in the board's brief do the defendants face

up to the fact of 21,000 black students remaining in all-black

schools, for example.

Second, the board's approach makes it seem logical and

just to generalize about long stretches of district court

litigation, masking any inconsistencies or differences in

position adopted by the parties. Thus, the board commences

its Statement of the Case as follows:

Since the August 29, 1972, decision of this Court

upholding the implementation of Plan A and

directing a plan of further desegregation, the

events of this case have followed two parallel

lines. The first of these has involved the con

clusion of appellate proceedings and the implemen

tation of the first busing in the Memphis School

System under Plan A. The second has been compliance

with the "additional instructions" contained in this

Court's Decision of August 29th directing the con

struction of a Final Plan of Desegregation.

(Brief for Defen. ants-Appellees, p. 2). The implications of

this summary are that the two processes occurred simultaneously

without interference one with the other; and that the board

without difficulty or resistance has proceeded to carry out

the judicial direction to eliminate "root and branch" the dual

school system in Memphis. This latter point is repeated in

self-congratulatory terms throughout the board's Statement of the Case. (cont'd)

-2-

But this is no minor concern, or side issue, for the

21,000 black pupils whom the Memphis school board and the

3/district court propose shall remain in all-black schools.

It has been the very heart of this lawsuit since its inception

in 1960. The "extreme western portion of Memphis" which the

school board willingly consigns to perpetual segregation is

t ______ _____________ ______________

2/ cont'd

A closer study of the proceedings in the district court

reveals, however, the inaccuracy of the board's general

description. There was no parallel development. At the urging

of the board, the district court postponed consideration of

developing a final plan until after the basis upon which Plan

A was to be implemented had been settled. The school board

not only wanted stays of any desegregation while it vainly

sought certiorari [despite the consistent Supreme Court

practice of denying such stays in all cases after Alexander

v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19 (1969) except

Corpus Christi Independent School Dist. v. Cisneros, 404 U.S.

1211 (1971), cert, denied, ___ U.S. ____ (1973)], but it also

succeeded in delaying Plan A implementation until the second

semester of the 1972-73 school year for elementary and junior

high schools, and until this school year for high schools.

And the fact that the school system thereafter planned for

the smooth implementation of an order which it at long last

admitted it could not overturn, amounts to no more than the

level of conduct we all have a right to expect from public

officials.

Finally, the board's style of factual presentation, when

combined with its major legal argument (see infra), puts it

on both sides of the legal street at the same time. If this

Court's reviewing function is to inquire only if the lower

court overstepped the bounds of equitable discretion, then it

must make that judgment based on the entire record and back

ground before the district court; it cannot simply approve or

disapprove the result below with reference only to selected

facts or circumstances.

3/ It is no answer to this concern that individual black

children and their parents may exercise rights under majority-

to-minority transfer provisions with free transportation. In

the first pi; ce, this is no measure of compliance with the

board ' s constitutional obligation. Majority-to-minority trans

fers have never in the past desegregated the school system.

See Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430

(1968). Furthermore, the transfer provisions provide only a

limited opportunity for these 21,000 black children. The

-3-

The blackthe historic, downtown, original area of the city,

schools which remain under the plan approved below are the

very racially segregated black schools whose elimination was

the goal when this action was filed. It is surely a pyrrhic

victory for the cause of the United States Constitution if

they must remain segregated after 13 years of litigation.

4/

The school board's proffer of excuses is but cold

comfort to these black children. Talk of "maintaining Plan

A desegregation," for example, translates to these children

to mean that they must be penalized now and hereafter because

the district court erred in approving an inadequate plan of

integration last year. The concern for an additional 1% of

3/ cont'd

entire "Plan II" was drafted in order to, among other goals,

balance facility utilization at an optimum level throughout

the system; thus, applicants for transfer must overcrowd schools in order to desegregate them. Finally, since it is totally

beyond the realm of expectation to imagine that any white

students will transfer to historically black schools, the

transfer provisions will "work" only at the cost of the dignity

of black students and their parents, who will watch a new

badge of racism become operative as white students are not

sent to black schools even if this results in closing down the facilities.

4/ In effect, through its intensive resistance to the imple

mentation of the Fourteenth Amendment throughout this case,

its annexation policies and the school construction practices

described in detail in our brief last year (No. 72-1630,

Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees, at pp. 16-21), Memphis had

established a new dual school system to replace the old by

opening a new set of schools for white Memphians to the east

of the original city system. Compare Clark v. Board of

Educ. of Little Rock, 401 U.S. 971 (1971), see Petition for

Rehearing En Banc, 6th Cir. , No. 71-1174; Swann v. Chariott.e-

Mccklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1, 20-21 (1971).

-4_

the school system's budget recalls to these pupils and their

parents this school board's decade-long school construction

program of unparalleled extravagance and segregative effect.

They can read the message between the lines— and it is one

which bespeaks of no moral determination in this Nation:

"Millions for segregated schools, but pennies for integration."

Blacks know whose interests are being cared for when the same

school board which sent black high school students to another

system, expresses its "deep and sincere" concern about an1/additional ten minutes on the bus.

The school board's legal argument deserves similar

6/

short shrift. Of course the district judge, ostensibly more

familiar with local conditions, is vested with considerable

discretion in fashioning a remedy for the unconstitutional

school segregation which has persisted in Memphis. But the

whole history of school desegregation in America reinforces

the importance of the reviewing courts in preventing district

judges from vitiating the constitutional guarantees in the

name of "local conditions." E.g., Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F.2d

33 (8th Cir.), aff'd 358 U.S. 1 (1958); Stell v. Savannah-

-̂ 7 The board suggests that Plan II routes, on an average

ten or fifteen minutes shorter than Plan I-III routes, will

allow more students to participate in extracurricular activities.

The logic escapes us. What extracurricular activities take

only fifteen minutes? Or is the board willing to provide an

extra bus to take students home from after-school activities

at 3:45 but not at 4:00?

V For example, the board's brief advances contentions in a

footnote (n.20) which were made to, and rejected by, the

district court and this Court in 1972.

-5-

Chatham Bd. of Educ., 333 F.2d 55 (5th Cir. 1964); Northcross

v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 466 F.2d 890 (6th Cir. 1972),

cert, denie , 410 U.S. 926 (1973).

Neither Goss v. Board of Educ., 6th Cir., No. 72-1766

(July 18, 1973), nor Lemon v. Kurtzman, 411 U.S. 192 (1973),

cited therein, requires affirmance of the ruling in this case.

This is neither the time nor the place for the parties to

debate their views of Goss ? its holding is simply that the

district court's action there was, under all of the facts

and circumstances, not clearly erroneous.

That holding is not mechanically applicable to the

instant case. And any use of Lemon v. Kurtzman in support of

affirmance would be unwarranted. The normal hesitance of

an appellate court to interfere with the affirmative remedial

aspects of a decree in equity is one thing, but the considera

tions are of a different sort when an equity court denies

relief, in whole or in part, since substantive legal notions

as well as remedial doctrines are thereby affected. Compare

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburq Bd. of Educ., supra, with Keyes

v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, ___ U.S. ____ (1973).

Even less are the theories suggested by the school

board useful in this case, for the district court's opinion

makes it clear that he was not holding Plan I-III busing

infeasible in the same technological sense as did the district

court in Goss. Rather, we believe the lower court's opinion

advances certain legal considerations accepted by that court

-6-

and based upon which it chose to leave 21,000 black students

in segregated institutions.

We close by noting that we are once again accused of

extremism by the school board (Brief for Defendants-Appellees,

at pp. 16-17). Our response is twofold: first, if counsel

for the class of plaintiffs are to be considered extreme for

attempting to enforce the personal Fourteenth Amendment rights

of 21,000 members of that class, then we accept that label.

Second, we direct the attention of the Court to our description

in last year's brief (No. 72-1631, Brief for Cross-Appellants,

at pp. 14-15) of the "compromise" process engaged in by the

district court.

The position which has been advanced by plaintiffs is

hardly extreme. We seek an additional expenditure equal to

1% of the school board's budget, for bus rides up to seven

minutes longer than were projected under Plan II (the school

system is using the expressway routes) in order to make the

Constitution meaningful for .over 21,000 black students in

what was, until implementation of the plan affirmed by this

Court in 1972, the nation's most segregated school system.

There can be no better incentive to extremism than the failure

of our legal institutions to bring to fruition the great

constitutional struggle against segregation in education.

-7-

The role of this Court is vital. The judgment below should

be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

LOUIS R. LUCAS,

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

ELIJAH NOEL, JR.Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Bldg.

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 26th day of September,

1973, I served two copies of the foregoing Reply Brief for

Appellants in the above-captioned matter upon counsel of

record for Appellees, by United States mail, air mail special

delivery postage prepaid, addressed to him as follows:

Ernest Kelly, Jr., Esq.

Suite 900

Memphis Bank Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

-8-