Wright v. The City of Brighton Alabama Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

May 18, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wright v. The City of Brighton Alabama Brief for Appellants, 1970. 9f9f0b97-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3eb9993a-7873-462d-99a2-c538f7b445e6/wright-v-the-city-of-brighton-alabama-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

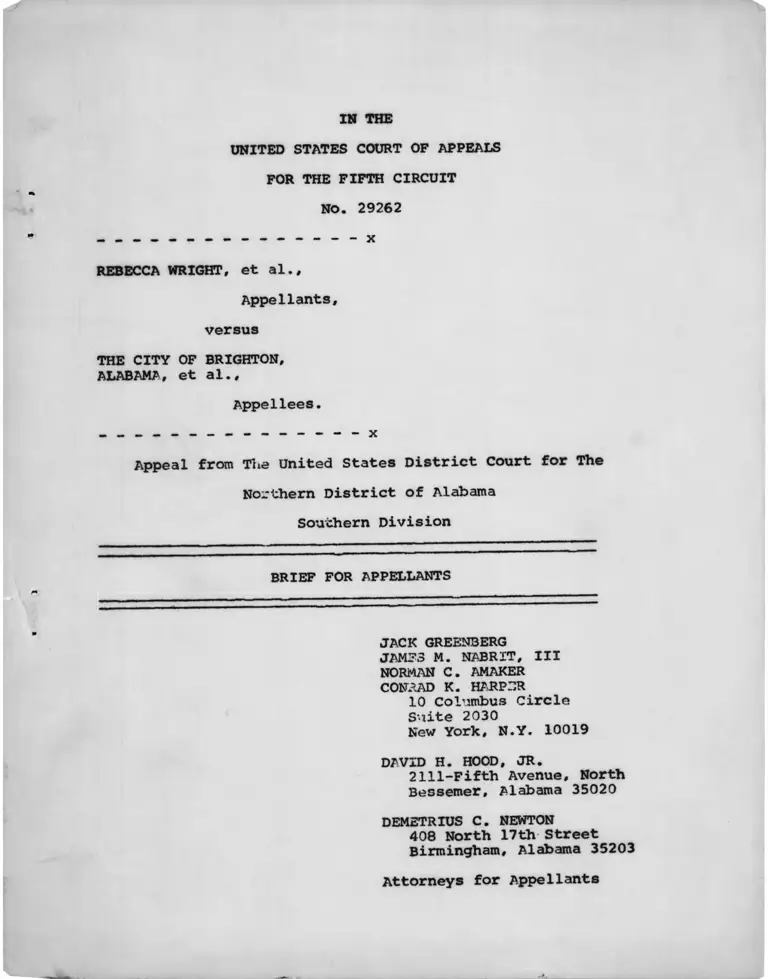

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 29262

- - - - - - - x

REBECCA WRIGHT, et al..

Appellants,

versus

THE CITY OF BRIGHTON,

ALABAMA, et al..

Appellees.

Appeal from The United States District Court for The

Northern District of Alabama

Southern Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN C. AMAKER

CONAAD K. HARPER10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030New York, N.Y. 10019

DAVID H. HOOD, JR.2111-Fifth Avenue, North

Bessemer, Alabama 35020

DEMETRIUS C. NEWTON408 North 17th Street Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Appe11ants

I N D E X

Statement of Issues Presented for Review ............

Statement of the Case ......................

Statement of Facts ..........................

Introduction ............................

Hoover Academy ................................

Argument

The Sale of Municipal Property to An Institution

With Knowledge by The Municipality of The Intended Discriminatory Use of The Property by The Buyer

Constitutes State Action in Violation of The

Fourteenth Amendment Where The Municipality

Maintains An Interest in The Property in The Form of A Purchase Money Mortgage ....................

A. The Purchase Money Mortgage Securedby The City of Brighton Provides

Continuing State Involvement in The Transaction ..........................

B. Municipal Ordinance 3-69 Authorizing

Sale of City Property for Racially

Discriminatory Purposes Violated 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983 ..................

Conclusion ....................

Certificate of Service ..............................

Appendix: Constitutional and Statutory ProvisionsInvolved

Page

iv

1

3

3

8

9

12

14

20

21

l

Table of Authorities:

Page

Cases:

V’ wilmingt°n Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715 viy61) • . ............................................... 6, 11, 12

Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F.2d 922 (5th Cir.1956). . 9, 10, 14

Evans v. Newton, 382 U.S. 296 (1966)................ 14 15

Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 (1880)................ 16, 17

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960).............. 17

H?5th°cir* C1962°f Jacksonville' Florida, 304 F.2d 320

’' ...................................... 6,13

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 285 (1969).................. 19

Jones v. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968).................. 16

Palmer v. Thompson, 419 F.2d 1222 (5th Cir., en banc 1970),

cert, granted, 38 U.S.L.W. 3405 (U.S. April 20, 1970) 15,16,18

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229 (1969) . . . . 16

Wimbish v. Penallas County Florida, 342 F.2d 804 (5th Cir., 1965)...................................... ..

Constitutional Provision:

Fourteenth Amendment........ 0 Q n _............................. ^ ^ / 1U

Statutory Provisions:

Ala. Code Tit. 37, § 404

Ala. Code Tit. 37, § 462

28 U.S.C. § 1343(3) . .

28 U.S.C. § 1343(4) . .

l i

42 U.S.C. § 1981

42 U.S.C. § 1983

Page

. 2, 14, 17, 18

........ 2, 14

iii

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 29262

REBECCA WRIGHT, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

THE CITY OF BRIGHTON, ALABAMA,

a Municipal Corporation, et al.,

Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court For The Northern

District of Alabama, Southern Division

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

The issues presented for review are:

A. The district court erred in dismissing the complaint

because enactment of an ordinance for the purpose of selling munici

pal real property to a racially segregated all-white school denied

black persons (a) equal benefit of all laws and proceedings, (b)

equal protection of the laws, (c) due process of law guaranteed by

42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983 and the Fourteenth Amendment.

B. The district court erred in dismissing the complaint

because knowingly selling municipal real property to a racially

segregated all-white school and continued municipality involvement

in the school violates the Fourteenth Amendment.

C. The district court erred in dismissing the complaint

because the school's racially segregated all-white enrollment

violates 42 U.S.C. § 1981 and the Fourteenth Amendment.

IV

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 29262

REBECCA WRIGHT, et al..

Appellants,

vs.

THE CITY OF BRIGHTON, et al..

Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District

Court for The Northern District of Alabama

Southern Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is an appeal from a judgment of the District

Court for the Northern District of Alabama, Southern Divi

sion, dismissing Black plaintif fs-appellants "-^complaint.

1/ Rebecca Wright, Ben Walker, Gus Dickerson, PearlieDavis and persons similarly situated pursuant to Rule 23

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

This action was filed August 27, 1969 against the

City of Brighton, Alabama; W.M. Perry, Fred West, Walter W.

Jenkins, Leonard Lewis, and Richard Lewis as members of

the City Council; E.B. Parsons individually and as Mayor,

and Hoover Academy of Hoover, Alabama. (2) The action was

brought pursuant to Title 28 U.S.C. Sections 1343(3) and

1343(4) as well as 42 U.S.C. Sections 1981 and 1983 and the

Fourteenth Amendment. (1) The complaint asserted that

defendants' action in seeking to lease facilities known as

the Old Brighton High School, to Hoover Academy, a private

school for whites only, violated the Fourteenth Amendment,

denying appellants and their class equal protection and due

process of law. (2) Appellant also moved the district court

for a preliminary injunction restraining defendants from

leasing, selling or contracting with Hoover Academy or other

persons except for the benefit of all persons without re

gard to race. (5)

The Motion for Preliminary Injunction came on for

hearing on September 5, 1969 and on September 15, 1969 the

court denied the motion. (66) Trial was had December 16,

1969 and by opinion and judgment filed December 29, 1969

the district court dismissed the complaint. On January 8,

1970 appellant filed notice of appeal.

...A" ■ v

2

STATEMENT OF FACTS

INTRODUCTION

The City of Brighton is a municipality of the State

of Alabama located in Jefferson County, Alabama with a

population of less than 6,000. (63) The City Council is

composed of six members: three blacks, two whites, and the

mayor who is white. (84) Pursuant to Alabama law the Mayor

may vote as a council member and must vote where there is

- 2/a tie. The building in question was purchased by the

City of Brighton, by bid, from the Jefferson County Board

of Education in 1966 following the Board's decision to

close the school. (173, 174) The school was within two

blocks of the Brighton City Hall, and remained vacant and

unused during the City's ownership. (174) On July 16, 1969

black Councilmen Walter E. Jenkins and Leonard Lewis offered

a resolution that the City of Brighton rent, lease or pur

chase the old Brighton Junior High School for the purpose

of housing all anti-poverty, community action, and food

stamp programs. (100) The City clerk, Mrs. Ellen Hindman,

testifying from the minutes stated the resolution was in

2/ Ala. Code, Title 37, Sec. 404

3

effect, tabled, because as worded was of a permanent nature

and could not be passed at the same meeting in which it was

introduced. (100) Mayor Parsons made the ruling on the

motion. (180)

The Council next met in regular session on August

6, 1969. (103) During discussion of the Jenkins-Lewis re

solution of July 16, a Mr. C.L. Smith sought recognition

from the audience. Mr. Smith was recognized and disclosed

that the Hoover Academy desired to submit a proposal to

lease the Brighton Junior High School building and re

quested an opportunity to submit a concrete proposal to

lease the property. (102) At this point, the council

3/ The complete text, from the minutes of the action

taken on the motion reads: Alderman and Jenkins moved

immediate adoption of the resolution. The motion was

seconded by Leonard Lewis. A discussion followed, and

it was disclosed that the resolution as it was worded

was of a permanent nature and could not be adopted at the

same meeting at which it was introduced unless unanimous consent of all members present was first obtained.

4/ One special meeting was held July 28, 1969 forthe purpose of discussing a sewage proposal. No matters material to this case were discussed. (234)

4

Blackrejected the Lewis-Jenkins resolution of July 16, ^

alderman West then moved that the Mayor be authorized to

negotiate with representatives of the Hoover Academy, the

motion was seconded and passed with 5 ayes, no nays and 1

pass. (103, 104) On August 12, 1969 at a special meeting1̂

of the Council an ordinance was introduced and passed

5/ Voting as read from minutes into record:Alderman Leonard Lewis, aye

" Richard Lewis, aye

" Jenkins, aye

" Wm. Perry, nayWest, nay

Mayor Parsons, nay

Whereupon the Mayor ruled the vote tied 3-3, passage had failed.

_6/ Mrs. Ellen Hindman, clerk treasurer, testified that

the August 12 meeting was a special meeting and that she notified Alderman Leonard Lewis, Walter Jenkins and Richard Lewis by

telephone the morning of the meeting. (108) Councilman Jenkins

testified later that Mrs. Hindman did not speak to him personally,

but that the message was left with his wife who informed of the

meeting upon his return from work approximately 5:15 p.m. (228)

Mrs. Hindman admitted that she did not inform any of the black councilmen of the purpose of the meeting (109)

Mayor Parsons testified and it is not disputed that he called the meeting and authorized the clerk to give notice. (142)

Ordinance No. 668, Section 3 adopted August 6, 1968 by the Brighton

City Council provided two methods of calling special meetings; the

first by the Mayor requiring 24 hour notice to members; the second

by any two members upon the Mayor's refusal to adhere to written

request to call a meeting. There is no time limit for notice specified on employing the second method. (129, 130)

5

purporting to authorize the Mayor to lease the building for two

years, with option to buy or renew the lease at the end of the

first two-year period. The vote on the ordinance was taken and

7 /passed 4-3 with Mayor Parsons voting twice and the three black

adlermen voting against the ordinance.

On August 27, 1969 the complaint and motion for

preliminary injunction were filed in the District Court. At

the hearing on the motion Friday, September 5, 1969 the court

indicated that the lease might fall within the proscription of

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715 (1961);

Hampton v. City of Jacksonville, Florida. 304 F.2d 320 (5th Cir.,

1962).(84) Whereupon the Mayor promptly called a special meeting^

of the council Monday, September 8, 1969 to consider "a proposal

submitted by Hoover Academy to accelerate its option to purchase

the Brighton Junior High School building." (117, 118)

7/ Following a general discussion on the proposed ordinanceNo. 2-69, read into the record at 15, 16, specifying terms and

conditions of the sale as voted on and the vote tied 3-3 whereon

Mayor Parsons stated that he did exercise his prerogative and duty

to cast a second affirmative vote, since the ordinance was not of a permanent nature. (107)

8/ Mrs. Hindman testified that there was no motion or

resolution to consider the sale of the property prior to September 8 meeting. (122)

6

Following passage of Ordinance No. 3-69 authorizing

the sale the Mayor signed the deed and received from the

9/Academy the purchase money mortgage. (176, 177) Although

the city clerk testified that the Ordinances 2-69 and 3-69

had been published, Mrs. Hindman at trial could produce no

certificate of publication^^ in what purported to be a copy

of Ordinance 2-69 authorizing lease (112) or Ordinance 3-69,

purportedly authorizing sale. (124) The original ordinances

were subpoenaed by appellants' attorneys. (124)

Mayor E. B. Parsons testified that at the July 16

meeting, wherein the original Lewis-Jenkins resolution was

introduced, he made the ruling that the resolution was of a

permanent nature and could not be acted on without

unanimous consent of council members present. (185, 186)

He further testified that following the August 16, 1969

meeting he met with Mrs. Jane Stanton, President of Hoover

9/ According to the terms of the mortgage the cityreceived $12,500; $500 cash payment on delivery of the deed;

$500 thirty days thereafter and the balance of $100 per month

on the purchase price of $12,500 until payment in full;

unpaid principal bearing interest at 6%; first payment due 60 days from date of delivery of deed.

10/ See Ala. Code Title 37, Sec. 462.

7

Academy stating that he initiated the negotiations with

Mrs. Stantoru (146) Mayor Parsons identified the original

ordinances 2-69 and 3-69 and stated that neither contained

certificate of publication by the clerk. (155, 156) The

Mayor further testified that at time of trial the all-

white Hoover Academy was the only school building within

the city limits. (181, 182)

Hoover Academy

Mrs. Jane Stanton as president of Hoover Academy

testified that no employees, board members or students at

the Academy were black, (188) nor had there been any blacks

connected with the school since its incorporation in 1963.

(193) The District Court found as fact from the evidence

that it was the policy of the school to accept only white

students. (85) Mrs. Stanton testified that she first be

came aware of the availability of the property in July of

1969. (194) Prior to bringing a written offer to purchase

11/ The record indicates that the court recessed for a brief period during which the subpoenaed ordinances were obtained. (136, 155)

8

the property to Mr. Norman Brown, City Attorney, September 3,

1969.(195) Mrs. Stanton testified she made overtures to the

City of Brighton to lease or purchase in July of 1969. (196

Argument

I.

THE SALE OF MUNICIPAL PROPERTY TO AN INSTI

TUTION WITH KNOWLEDGE BY THE MUNICIPALITY

OF THE INTENDED DISCRIMINATORY USE OF THE PROPERTY BY THE BUYER CONSTITUTES STATE

ACTION IN VIOLATION OF THE FOURTEENTH AMEND

MENT WHERE THE MUNICIPALITY MAINTAINS AN

INTEREST IN THE PROPERTY IN THE FORM OF A PURCHASE MONEY MORTGAGE

The district court in finding no discrimination in

the sale of the building to Hoover Academy relied on Derrincrton

v. Plummer. 240 F.2d 922 (5th Cir., 1956). (89) Judge Rives,

speaking for the Court stated, 240 F.2d at 925, "no doubt the

county may in good faith lawfully sell and dispose of its

surplus property, and its subsequent use by the grantee would

not be state action. Likewise, we think that, when there is

JL2/ The record shows however that defendants' counsel in

open court acknowledged that negotiations to purchase or sell

were caused in part by the court's questions on the legality of the lease at the motion hearing. (241)

9

no purpose of discrimination, no noinder in the enterprise, or

reservation_of control by the county, it may lease for private

purposes property not used nor needed for county purposes, and

the lessee's conduct in operating the leasehold would be merely

that of a private person." (Emphasis supplied) The court went

on to hold that these principles did not apply to that case

because: (1) The courthouse could not be deemed surplus

property not used nor needed for County purposes, and (2) the

service rendered by the lessee would clearly be violative of

the Fourteenth Amendment if rendered by the lessor. "The same

result invitably follows when the service is rendered through

the instrumentality of a lessee; and in rendering such service

the lessee stands in the place of the County. His conduct is

as much state action as would be the conduct of the County

itself." 240 F.2d at 926. It is not sufficient to state that

the instant case deals with a sale and not a lease, where the

state seller knew the nature of the Academy's existing

operation and its planned use of the property in question.

(195, 196) The specific test noted in Derrington v. Plummer,

supra, was "when there is no purpose of discrimination, no

joinder in the enterprise." The question then becomes one of

whether the sale, made to render an unconstitutional

transaction constitutional-^^is sufficient joinder in the

13/ It is clear from the record that the agreement to

sell came only upon disclosure by the district court at the

motion hearing that the proposed lease would probably fall

within the proscription of Derrinqton v. Plummer, supra. (84)

10

purpose of the enterprise and reservation of control to

constitute state action. In Burton v. Wilmington Parking

Authority, 365 U.S. 715, 722 (1961) the Court noted that to

fashion and apply a precise formula for recognition of state

responsibility is an "impossible task" which the Supreme

Court has never attempted. "Only by sifting facts and

weighing circumstances can the non—obvious involvement of

the State in private conduct be attributed its true

significance." 365 U.S. at 722.

In Wimbish v. Penellas County Florida. 342 F.2d 804

(5 th Cir., 1965), this Court held that tenant's denial of use

of golf course by blacks was "state action." Racial discrimina

tion was prohibited by the Fourteenth Amendment where the county

leased land to a tenant who was obligated to use premises only

for a golf course, the county had to approve the tenant's plans

and specifications for improvements, title to improvements vested

in county, prices charged for golf fees were subject to approval

by county and tenant was required to establish daily membership

or green fees, notwithstanding that county had no purpose of

discrimination in execution of the lease.

In the instant case the City of Brighton's sale must be

viewed as joinder in purpose as construed in Wimbish. supra.

The city did not begin negotiations for the lease until the

11

black councilmen moved to use the building to house anti-

proverty programs in the city. (98, 99) The city did not

begin negotiations for sale until the district court

suggested a lease with a racially discriminatory lessee

might be unconstitutional. The sale was thus tainted at

its inception.

A* THE PURCHASE MONEY MORTGAGE SECURED BY THE

CITY OF BRIGHTON PROVIDES CONTINUING STATE INVOLVEMENT IN THE TRANSACTION

The City of Brigton received from the Hoover

Academy a purchase money mortgage September 9, 1969. (176,

177) (Def. Exhibit 5) The City required the Academy to

purchase insurance on the building (178) and is named

mortgagee in the policy. (179) At the time of the execution

of the mortgage and sale agreements, the City had knowledge of

Hoover's intended use of the building as a school. in the

Wimbish case, supra, the court held that the degree of

involvement by the county was in no way diminished because its

reasons for securing the lease were good faith ones. The court,

citing Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, supra, states:

(342 F.2d at 806 )

"It is of no consolation to an individual

denied the equal protection of laws that it

12

any

was done in good faith. Certainly the cases

by the various Courts of Appeals do not depend

upon such a distinction."

The facts of the instant case do not indicate

showing of good faith in the execution of the sale, or

tangentially, the purchase money mortgage agreement (see

footnote 1, supra). Appellants submit that coupled with

the knowledge of the intended use of the building by Hoover

Academy, intent to establish a segregated Academy may be

imputed to Appellees. In Hampton v. City of Jacksonville.

Florida, 304 F.2d 320 (5th Cir., 1962 ) this Court held:

( 304 F . 2d at 322 )

"Conceptually, it is extremely difficult,

if not impossible to find any rational basis

of distinguishing the power or degree of con

trol, so far as related to the state's involve

ment, between a long-term lease for a particular

purpose with a right of cancellation of the lease

if that purpose is not carried out on the one

hand, and an absolute conveyance of property,

subject, however to the right of reversion if

the property does not continue to be used for

the purpose prescribed by the state in its deed

of sale . . . . "

13

The original intent of the appellees was to

establish a long term lease. (101, 102) The freehold

conveyance to the Academy was born of appellees' discovery

of a legal proscription against such leases. The degree of

control retained by the city may be considered marginal

when considered singly but must be viewed in conjunction

with (a) the joinder of purpose in the enterprise described

in Derrington, supra; (b) the dubious "surplus" nature of

the property when considered in light of attempts by the

black councilmen to convert it to a purpose from which the

entire community could benefit; and (c) the traditionally

governmental services provided by Hoover Academy. See Evans

v. Newton. 382 U.S. 296.

B. MUNICIPAL ORDINANCE 3-69 AUTHORIZING SALE

OF CITY PROPERTY FOR RACIALLY DISCRIMINA

TORY PURPOSES VIOLATED 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983.

The District Court in holding that the city had a

right to sell its surplus property found there was no dis

crimination in so doing. (86) The Court added:

11 • • . it would be a strange perversion of a

constitutional right to sell and dispose of property if

there was a legal interdiction running with the land that

the property would not be used for the purpose of establish

ing a private school, even though the school admitted only

14

white students." Appellants submit that this finding is

error. The right of Black citizens to equal benefit of

all laws is the substantive right to be considered in the

context of the City's right to dispose of its property. (86)

In the instant case, the city sold a public

facility for the purpose of curing an illegal lease of the

same property with knowledge that the necessary effect of

such sale would be to establish a segregated educational

institution in the city.

In the Evans case, supra, the city government

attempted to escape desegregating a facility by terminating

the city’s connection with the facility. in the instant

case the objective of the city was institution of a

segregated facility, and the method employed was outright

sale to terminate the city's connection with the facility.

In ?almer v. Thompson. 419 F.2d 1222 (5th Cir., 1969) this

Court stated the issue involved was "whether the Constitution

forbids the City of Jackson from withdrawing a badge of

equality . . . it cannot be disputed that were the badge

of equality, here the ability to swim in an unsegregated

swimming pool, to be replaced by a badge implying inequality -

segregated pools, the municipality's action could not be

allowed . . . " 419 F.2d at 1227 in the instant case a

"badge of inequality" is unquestionably attached to the black

citizens of Brighton as a result of the placement of a Hoover

Academy in their midst by the act of their city council. The

15

majority in Palmer, supra, held that where facilities are removed

from the use and enjoyment of the entire community, there was no

withdrawal of any badge of equality as to any racial group. The

equal right in the instant case was in the vacant building.

Although vacant, as city property black citizens held the same

interest in the building as white citizens but after the sale

blacks lost this equality. Nor is it an answer that black

citizens shared equally in the consideration received by the city

for the sale. In any sale by a municipality of facilities to

private individuals to perform a service or function public

in nature or general in character, part of the consideration

is the undertaking of the function and its usefulness and

benefit to the community. Since Hoover Academy refuses blacks,

they cannot be said to have shared equally with white citizens

in the ordinance permitting sale. This being so, the require

ment of § 1981 that blacks share equally in all "laws and

proceedings" has been violated. Cf. Jones v. Mayer Co.. 392

U.S. 409 (1968); Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park. 396 U.S. 229

(1969).

In Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 the Court stated:

"The controlling legal principles are plain. The command of

the Fourteenth Amendment is that no "State shall deny to any

person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the

laws. 'A State acts by its legislative, its executive, or

16

its judicial authorities. It can act in no other way. The

constitutional provision, therefore, must mean that no

agency of the State, or of the officers or agents by whom

its powers are exerted shall deny to any person within its

jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. Whoever, by

virtue of public position under a state government, . . .

denies or takes away the equal protection of the laws,

violates the constitutional inhibition', and as he acts in

the name and for the State, and is clothed with the State's

power, his act is that of the State. This must be so, or

the constitutional prohibition has no meaning.' Ex Parte

Virginia. 100 U.S. 339, 347.

State authority is not insulated from judicial

control "when state power is used as an instrument for cir

cumventing a federally protected right. Gomillion v.

Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339, 347 (1960). In many cases said

Justice Frankfurter the court has "prohibited a State from

exploiting a power acknowledged to be absolute in an

isolated context." 364 U.S. at 347

Section 1981 provides that "All persons within

the jurisdiction of the United States shall have the same

right in every State and Territory to make and enforce

contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the

full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the

security of persons and property as is enjoyed by white

17

citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains,

penalties, taxes, licenses and exactions of every kind and

to no other."

In Palmer v. Thompson, supra, this Court, in

denying plaintiffs1 claim that closure of all municipal

swimming pools by the City of Jackson, Mississippi to avoid

desegregation violated their right to equal protection of

the laws held that "Motive behind a municipal or a legislative

action may be examined where the action potentially interferes

with or embodies a denial of constitutionally protected rights."

Palmer v. Thompson, supra,at 1228. In the Palmer case the Court

stated: "The equal protection clause is negative in form, but

there is no denying that positive action is often required to

provide 'equal protection.' That is frequently true as to

essential public functions. Other functions permit more latitude

of action . . . " 419 F.2d at 1226. There can be no doubt that

the functional purpose of the sale was to house an educational

institution on a racially segregated basis, a purpose denying

the § 1981 guarantee of "equal benefit of all laws."

While we doubt Palmer was rightly decided and we note

the Supreme Court has granted certiorari, 38 U.S.L.W. 3405

(U.S. April 20, 1970), we do not believe it is controlling

here because the Palmer majority clearly was concerned about

possible violence at Jackson, Mississippi's desegregated

18

swimming pools as a reason sustaining the closing of the

pools. Here there is no hint of violence in the record;

indeed the selling of public land and a building for

discriminatory purposes may increase rather than decrease

the chance of violence.

In Hunter v. Erickson. 393 U.S. 285 (1969) where

the City of Akron, Ohio amended its charter to prevent the

city council enacting an open housing ordinance without

the approval of a majority of voters, the Court found a

denial of equal protection in that "only laws to end

housing discrimination based on 'race, color, religion

national origin or ancestry must run §137's gauntlet." 393

U.S. at 390 . In the instant case the ordinance effects a

discrimination as clear and an inequality as blatant as the

ordinance in Hunter, supra. The Brighton ordinance was

conceived to aid Hoover Academy in its purpose of providing

racially segregated education. Appellants submit that this

is the requisite participation to constitute state action

in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and the substantive

ii^snt and effect of the sale and the ordinance authorizing

it denied appellants "full benefit of all laws and proceedings"

as is enjoyed by white citizens.

19

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the district court

should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted.

u r \ \ ~ xx VJXXUX^L>li3XjX\Vor

NORMAN C. AMAKER

CONRAD K. HARPER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

DEMETRIUS C. NEWTON

408 North 17th Street

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Dated: May 18, 1970.

20-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that on the 18th day of May, 1970

the undersigned, one of counsel for appellants, served two

copies each of the foregoing Brief for Appellants upon appellee.

City of Brighton, represented by Mr. Brown and upon appellee,

Hoover Academy, represented by Mr. Locke, by mailing same via

United States mail postage prepaid, addressed as indicated below:

Norman K. Brown, Esq.

Realty Building

Bessemer, Alabama

Hugh Locke, Esq.

923 Frank Nelson Building Birmingham, Alabama

21

A P P E N D I X

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case involves the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution.

This case also involves 42 U.S.C. § 1981:

All persons within the jurisdiction of

the United States shall have the same right in every State and Territory to make and

enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give

evidence, and to the full and equal benefit

of all laws and proceedings for the security

of persons and property as is enjoyed by

white citizens, and shall be subject to like

punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses,

and exactions of every kind, and to no other.

This case also involves 42 U.S.C. § 1983:

Every person who, under color of any

statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or

usage, of any State or Territory, subjects,

or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the

United States or other person within the

jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any

rights, privileges, or immunities secured by

the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to

the party injured in an action at law, suit in

equity, or other proper proceeding for redress.

I •