Duckworth v. Moore Appellant's Brief

Public Court Documents

May 4, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Duckworth v. Moore Appellant's Brief, 1977. 4c5a7a43-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3eeee6f8-51d7-428f-bad5-65e70ed0c746/duckworth-v-moore-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

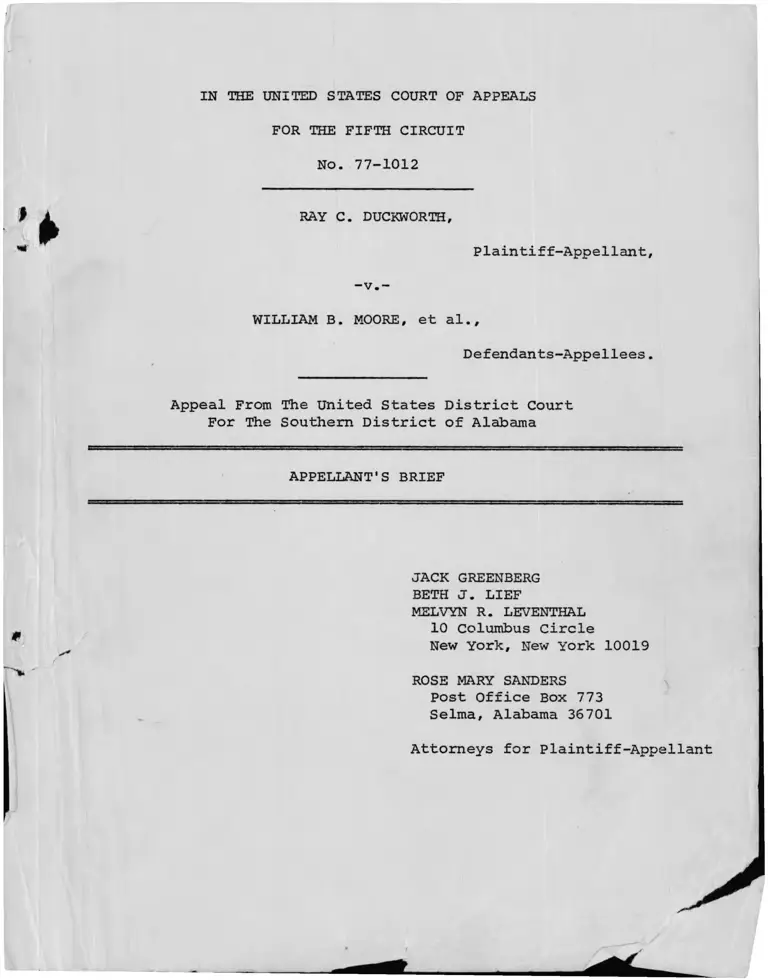

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 77-1012

RAY C. DUCKWORTH,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

-v.-

WILLIAM B. MOORE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District of Alabama

APPELLANT'S BRIEF

JACK GREENBERG

BETH J. LIEF

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ROSE MARY SANDERS

Post Office Box 773

Selma, Alabama 36701

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

INDEX

Statement of the Issues Presented ...................... 1

Statement of the Case ................................... 2

Statement of Facts ...................................... 8

A. The undisputed Facts ........................... 8

B. Other Evidence Adduced at Trial ............... 18

Argument

I. On The Basis Of The Uncontradicted

Evidence, Plaintiff Duckworth Was

Denied Housing And Victimized By

Racially Discriminatory Practices ......... 21

II. On The Uncontested Facts, Plaintiff

Established Class Violations Of The

Fair Housing Laws By Defendants And

The District Court Erred In Its Denial

Of Injunctive Relief For Plaintiff And

The Plaintiff Class ........................ 30

III. Defendants Moore, Jr., And Welch, As

Owners And Principals Of Les Chateaux

And River Oaks, Are Legally Liable For

The Discriminatory Conduct Of Their

Agent ....................................... 34

A. The District Court Erred In Granting

A Directed Verdict And Dismissing The

Complaint As To Defendants Moore, Jr.,

And W e l c h .............................. 34

B. The Erroneous Dismissal Of The

Principals So Prejudiced The

Plaintiff's Case As To Necessitate

A Redetermination Of Liability For

All Defendants......................... 39

IV. The Jury Instruction On Burden Of Proof

Misstated The Law And Requires Reversal

Of The Case ................................ 41

CONCLUSION ............................................... 4 3

Page

Table of Cases

Adickes v. Kress & Co., 398 U.S. 144 (1970) ........... 33

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975)..... 43

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972) 27

Banks v. Perks, 341 F. Supp. 1175 (N.D. Ohio

1972) .................................................. 26

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Mach. Co., 457 F.2d

1377 (4th Cir. 1972), cert, den. 409 U.S. 982

(1972) ................................................ 30,32

Bullock v. Tamiami Trail Tours, Inc., 266 F.2d

326 (5th Cir. 1959) .................................. 22

Burris v. Wilkins, 544 F.2d 891 (5th Cir. 1977)....... 42

Contract Buyers' League v. F&F Invest. Co., 300

F. Supp. 210 (N.D. 111. 1969), aff1d 420 F.2d

1191 (7th Cir. 1970) ................................. 29

Franks v. Bowman, __ U.S. __, 47 L.Ed.2d at 456,

n. 7 (1976) ........................................... 30

Glazer v. Glazer, 374 F.2d 390 (5th Cir. 1967) ........ 21

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1970).......... 29

Haythe v. Decker Realty Co., 468 F.2d 336 (7th

Cir. 1972) ........................................... 29

Huff v. N.D. Cass Co. of Alabama, 485 F.2d 710

(5th Cir. 1973) ........................................ 30

Hughes v. Dyer, 378 F. Supp. 1305 (W.D. Mo. 1974)..... 39

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28 (5th

Cir. 1968) ........................................... 30

Johnson v. Jerry Pals Real Estate, 485 F.2d 528

(7th Cir. 1973) ....................................... 25, 29

Jones v. Mayer, 303 U.S. 409 (1968) ............... Passim

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp., 429 F.2d

290 (5th Cir. 1970) .................................... 38

Page

11

Table of Cases (Continued)

Lyles v. Hampton, Prentice-Hall Equal Opportunity

in Housing Reporter, 5 13,738 (S.D. Ohio 1975).... 35

Marr v. Rife, 503 F.2d 735 (6th Cir. 1974) .......... 34,36

McPherson v. Tamiami Trail Tours, Inc., 383

F . 2d 527 (5th Cir. 1967) ........................... 21

Moore v. Townsend, 525 F.2d 482 (7th Cir. 1975)..... 34, 42

Nesbith v. Alford, 318 F.2d 110 (5th Cir. 1963)..... 22,

Newbem v. Lake Lorelei, Inc., 308 F. Supp. 407

(S.D. Ohio 1963) ................................ 23, 24,43

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 433

F.2d 28 (8th Cir. 1970); cf. Jenkins v. United

Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28 (5th Cir. 1968)............. 3 0

Rowe v. General Motors, 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir.

1972) 31

Seaton v. Sky Realty Co., 491 F.2d 634 (7th Cir.

1974) 26

Sims v. Georgia, 389 U.S. 404 (1967) ................ 27

Singleton v. Jackson Mun. Sep. School Dist.,

419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1970), cert. den. 396

U.S. 1032 (1971) .................................... 31

Smith v. Concordia Parrish School Bd., 445 F.2d

285 (5th Cir. 1971) 31

Smith v. Sol Adler Realty Co., 436 F.2d 344 (7th

Cir. 1971) .......................................... 29,31

Spurlin v. General Motors Corp., 528 F.2d 612

(5th Cir. 1976) ..................................... 21, 22

State of Alabama v. United States, 371 U.S. 583

(5th Cir. 1962), aff*d 371 U.S. 37 (1962)............ 22

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S.

229 (1969) .......................................... 37

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970) .................. 27

Page

x n

Table of Cases (Continued)

Page

United States Broadcasting Co. v. Armes, 506 F.2d 766

(5th Cir. 1975) ...................................... 22

. United States v. Berg Enterprises, Prentice-Hall

Equal Opportunity in Housing Reporter, f 13,773

(S.D. Fla. 1976)...................................... 35

United States v. Bob Lawrence Realty, 474 F.2d

115 (5th Cir. 1973) ................................. 37

United States v. Bucon Construction Co., 430 F.2d

420 (5th Cir. 1970); accord, Massey v. Gulf

Oil Corp., 508 F.2d 92 (5th Cir. 1975) ............. 22

United States v. Hinds County Board of Education,

. 417 F. 2d 852 (5th Cir. 1969) ........................ 23

■ United States v. L & H Land Corp., Inc., 407

F. Supp. 576 (S.D. Fla. 1976) ....................... 35

United States v. Mintzes, 304 F. Supp. 1305

(D. Md. 1969) ........................................ 26

j

. United States v. Mitchell, 335 F. Supp. 1004

(N.D. Ga. 1971) .................................... 35,37

United States v. Northside Realty Associates,

Inc., 518 F . 2d 844 (5th Cir. 1975) ......... 22,34,3 5,37

-United States v. Pelzer Realty Co., 494 F.2d 438

(5th Cir. 1973), cert, den., 416 U.S. 936

j ' (1974) ........................................ 27,42

— United States v. Real Estate Development Corp.,

347 F. Supp0 776 (N.D. Miss. 1972)...... Passim':

— 1 United States v. Reddoch, 467 F.2d 897 (5th

Cir. 1972) ................................. Passim

United States v. West Peachtree- Tenth Corp.,

437 F . 2d 221 (5th Cir. 1971) ................... 2 7, 33

United States v. Youritan Construction Co., 370

F. Supp. at 642 (N.D. Cal. 1973) , aff1d, 509

F.2d 623 (9th Cir. 1975) ................ Passim

iv

Table of Cases (Continued)

Urti v. Transport Commercial Corp., 479 F.2d

766 (5th Cir. 1973) ............................. 21

Williams v. Matthews, 499 F.2d 819 (8th Cir.

1974) ........................... 22,23,27, 32

Williamson v. Hampton Management Co., 339

F. Supp. 1146 (N.D. 111. 1972) ................. 25, 26,35

Wright v. Kaine Realty, 352 F. Supp. 222

(N.D. 111. 1972) ................................ 38

Zuch v. Hussey, 394 F. Supp. 1028 (E.D. Mich.

1975) , aff'd 547 F.2d 1168 (6th Cir. 1977)..... 25

Page

v

Statutes

Page

Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States .................................... 2

42 U.S.C. §3613 ..................................... 36

42 U.S.C. §3601, e_t seq.. Fair Housing Act

of 1968 .......................................... 2, 39

42 U.S.C. § 1982 ................................... 2, 38,

42 U.S.C. § 1983 .................................... 38

28 U.S.C. § 1343(3) and (4) ........................ 2

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (Rule 23(b) (2) ... 3

6A Moore's Federal Practice 5 59.08 [5] at

pp. 59-152 ....................................... 21

IN HIE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 77-1012

RAY C. DUCKWORTH,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

-v. -

WILLIAM B. MOORE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District of Alabama

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY LOCAL RULE 13(a)

The undersigned counsel for Plaintiff-Appellant Ray C.

Duckworth certifies, in conformance with Local Rule 13(a), that

the following listed parties have an interest in the outcome of

this case. These representations are made in order that Judges

of this Court may evaluate possible disqualifications or recusal:

1. Ray C. Duckworth, plaintiff.

2. William B. Moore, Harry Welch, William B. Moore, Jr.,

Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellant

defendants.

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 77-1012

RAY C. DUCKWORTH,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

-v. -

WILLIAM B. MOORE, et al.,

Defendant-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District of Alabama

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY LOCAL RULE 13(j) (2)

Plaintiff-Appellant believes that oral argument would be

helpful to a resolution of the issues in this case, as they

entail consideration of the entire evidence presented. Accord

ingly, plaintiff-appellant urges this Court to permit him an

opportunity to answer at oral argument questions which may be

raised by the briefs on appeal.

Statement of the Issues Presented

1. Whether the defendants, as a matter of law,

unlawfully discriminated in refusing to rent an apartment to

plaintiff, or whether the "clear weight of the evidence"

permitted only that conclusion and consequently, whether

the district court erred in denying the motions for a directed

verdict, for judgment notwithstanding the verdict, or, in the

alternative, for a new trial.

2. Whether in light of uncontroverted policies and

practices of racial discrimination the district court erred

in denying injunctive relief to plaintiff and the plaintiff class.

3. Whether the district court erred in holding that as a

matter of law, the owners and principals, defendants Moore, Jr.,

and Welch were not liable for the unlawful discrimination of

their agent, Moore, Sr., and whether the dismissal of these

defendants so prejudiced and tainted the jury's verdict as to

mandate reversal of the case.

4. Whether the jury instructions on the elements of

proof in a fair housing case charging racial discrimination

misstated the law and failed to provide guidance and standards

necessary to reach a lawful verdict.

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 77-1012

RAY C. DUCKWORTH,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

-v.-

WILLIAM B. MOORE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District of Alabama

APPELLANT'S BRIEF

Statement of the Case

The appellant in this case, a black man employed by the

United States Department of the Air Force, charges defendants

with racial discrimination in the rental of units in two apart

ment complexes in Selma, Dallas County, Alabama. Jurisdiction

in the Court below was predicated on 28 U.S.C. § 1343(3) and (4);

plaintiff alleged violations 'of his right under 42 U.S.C. § 1982

1/and the Thirteenth Amendment to secure a dwelling without discrim

ination on the basis of race or color (A. 4, 267 ). This appeal

challenges the district court's refusal to grant a directed

1/ The complaint also alleged violations of the 1968 Fair Housing

Act, 42 U.S.C. § 3601 et seq.; the district court dismissed this

cause of action for failure to file within 180 days.

- 2 -

verdict for plaintiffs in light of the undisputed proof of

racial discrimination. Plaintiffs also appeal the district

court's exculpation of the owners and principals of the apart

ment complexes from any liability for the racially motivated

conduct of their agent, the denial of any class and individual

injunctive relief, and the giving of improper jury instructions.

The action began on January 12, 1976 when the complaint was

filed in the United States District Court for the Southern District

of Alabama. Plaintiff Ray C. Duckworth alleged that he visited

Les Chateaux Apartments on two occasions in July, 1975; that the

manager of the complexes, defendant william B. Moore, Sr., stated

that there were no vacancies; but that a Caucasion couple had been

offered and had declined to take an apartment during the period

between plaintiff's two visits to Les Chateaux. In essence, plain

tiff alleged that defendants discriminatorily refused to rent him

an apartment because of his race. The complaint further alleged

that an investigation by the Department of the Air Force conclud

ed that defendants had unlawfully discriminated against plaintiff

Duckworth and, because of that discrimination, imposed a one hund

red and eighty (180) day sanction prohibiting Department of

Defense personnel from leasing or renting from defendants at Les

Chateaux and River Oaks Apartments (A. 6-8).

Plaintiff brought the action pursuant to Rule 23(b)2 of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure on behalf of all blacks who are

or may be in the future barred from renting apartments at Les

-3-

Chateaux and River Oaks by defendants' racially discriminatory

practices. Injunctive and declaratory relief was sought for

the class; plaintiff sought, in addition, compensatory and pun

itive damages and attorneys' fees.

2/

On January 27, 1976 defendants William B. Moore, Harry

Welch and William B. Moore, Jr., answered, and admitted that the

Les Chateaux and River Oaks apartment complexes are owned by

William B. Moore, Jr., and Harry W. Welch;and that William B.

Moore, Sr., is employed to manage both apartment complexes. By

their answer, defendants denied that they engaged in unlawful

discrimination and denied "each and every material allegation"

concerning plaintiff Duckworth's attempts to rent apartments (A.

12-13) .

On April 21, 1976, after having heard oral argument, the Court

certified the action as a class action for purposes of injunctive

relief (A. 15) .

The case was tried before a jury on November 1 and November

3, 1976. At the close of the testimony, both the plaintiff and

defendants moved for directed verdicts (A. 331, 335). The

2/ On January 22, 1976 the defendants' motion to dismiss was

denied for failure to file a brief as required by local court

rules (A. 11) .

-4-

district court found that the fact that the population of Dallas

County is approximately fifty per cent (50%) black, that the

apartments have not a single black tenant,and that plaintiff

Duckworth applied for apartments but failed to obtain one made

out a "prima facie case under the law that would require that the

defendants come forward with sufficient proof to demonstrate

that it was guilty of no discrimination" (A. 335-336). On the

basis of these facts the district court denied the motion for a

directed verdict as to the manager of the complexes, William B.

Moore, Sr. While the district judge also stated, "By the pre

trial documents [defendants] Mr. Moore, Jr., and Mr. Welch assume

the responsibility of liability for the actions of their agent,

Mr. Moore, Sr.," the judge nevertheless granted a directed verdict

and dismissed the action as to the owners and principals of the

apartments for the following reasons:

(1) The principals and owners can only assume

liability for actions taken by Moore, Sr., within

the scope of his employment as agent of defendants

(A. 336) .

(2) There was no "willful participation" by the

principals in the discriminatory conduct (A. 336).

(3) Moore, Jr., and Welch learned of the discrim

inatory behavior when they received word from Craig Air

Force Base and there was no evidence that "they ratified

his actions" (A. 336-337).

(4) Moore, Jr., testified that he instructed his

agent about the Fair Housing Laws (A. 337).

The case against the sole remaining defendant, the eighty

year old agent of the apartments, went to the jury which found

for the defendant (A. 361) .

On November 11, 1976 the district judge denied equitable

relief for the plaintiff and the plaintiff class (A. 34).

Plaintiff Duckworth moved on November 9, 1976 for judgment

in accordance with his motion for a directed verdict or, alterna

tive, for a new trial (A. 35-36). By order dated November 19,

1976 the district court denied the motion (A. 37-41). In so

ruling, the district court agreed with plaintiffs' statement

of the law that:

"the discriminatory conduct of an apartment

manager, rental agent, or other individual

acting in a representative capacity is at

tributable to the owner, manager, or other

principal, both under the doctrine of re

spondent superior and because the duty to

obey the law is non-delegable" (A. 37-38) .

Despite its acknowledgement that the duty to obey Fair Housing Laws

is non-delegable, the court nevertheless adhered to its original rul

ing on the grounds that "the scope of the agency included compliance

with requirements of the Fair Housing Act. Any act which was

-6-

allegedly racially motivated was outside the scope of the

agency involved in this case" (A. 40-41).

On December 6 , 1976 plaintiff Duckworth timely filed

his notices of appeal from the denial of his motions for a

judgment in accordance with the motion for a directed verdict

or for a new trial, and from the denial of equitable relief to

plaintiff and the plaintiff class (A. 42-43).

-7-

Statement of Facts

A. The Undisputed Facts

Defendant William Moore, Jr., and Harry Welch, who are

white, own two apartment complexes in Selma, Dallas County,

Alabama (A. 104, 273). Les Chateaux was opened in 1969 and

contains 48 units; River Oaks, which opened in 1966, contains

30 units (A. 48). Since the complexes were opened, not a single

one of defendants' 78 units has ever been rented to blacks,

despite the fact that the population of Dallas County is 52%

black (A. 45, 335-336).

Defendant William Moore, Sr., who is white, is the agent

of defendants William Moore, Jr. and Harry welch, and was hired

to manage both Les Chateaux and River Oaks. He has been manager

of each complex since they opened and, as such, has been delegated

authority over the day-to-day supervision of the apartments,

including maintaining them in good order and renting them

(A. 50-51, 54, 253, 274). Although defendants Moore, Jr. and

Welch have not given him specific written or oral instructions

on how to perform his duties (A. 52-53, 282, 284), Moore, Sr.,

meets with Welch to discuss policies concerning the apartments

whenever it is necessary and talks to Moore, Jr., frequently

(A. 116, 283, 324).

8

Defendants' methods and criteria for accepting tenants are

’ 2/

informal and, except for rules not relevant here, totally sub

jective. Vacancies at either complex are never advertised; one

can only learn about the availability of apartments by asking

Moore, Sr. (A. 55). Prospective tenants need not fill out any

applications. Although credit checks are not made regularly or

according to any objective criteria, references are verified

"sometimes," if an applicant "looks doubtful" (A. 61).

There are two procedures, however, that defendants regularly

follow. First, defendants insist that prospective tenants have a

face-to-face interview. The defendant Moore, Sr., will only ac

cept those applicants who "look decent" (A. 57-58, 60). Second,

defendants "very seldom" reserve an apartment for any person who

will not rent immediately. As Moore, Sr., testified "[i]f we

do it, it is just for two or three days," and normally seven

days is "too long" (A. 62-63). Defendants have never waived the

requirement of a face-to-face interview. During the almost ten

years that they have owned and operated apartment complexes, the

only time,defendants testified, that they deviated from their

rule of holding apartments for not more than a week was during the

2/ Pets are forbidden at both complexes and children are not

allowed at River Oaks (A. 60).

- 9 -

There were at least three vacancies at Les Chateaux

during July, 1975, when plaintiff Duckworth twice sought and

was refused an apartment: according to defendants' testimony

and business records, apartment 8 was vacant from June 15 to

August 15; apartment 34 was vacant during July and August; and

apartment 41 was vacant from June 15 through August 15 (A. 111-113).

Plaintiff Ray Duckworth is a single black man who holds

a bachelor's degree. For two and a half years prior to moving

to Selma, he was employed by the Department of Defense, Air

Training Command, at Chanoot Air Force Base, Champagne, Illinois.

In July, 1975, he was transferred to Craig Air Force Base in

Selma to assume the position of Personnel Management Specialist,

the same position he held at Chanoot Air Force Base. Pursuant

to his reassignment orders, Duckworth arrived in Selma on

Sunday, July 6 , 1975 and rented a room at a motel (A. 156-158).

In order to ease plaintiff Duckworth's transfer to a new

city, Craig Air Force Base assigned him a sponsor, Randy Houston,

who was a Personnel Management Specialist. Houston's responsi

bility was to help the plaintiff get settled and to assist him in

finding housing (A. 136). On July 7, 1975, the first full day

that Duckworth was in Selma, Houston drove Duckworth around

various apartment complexes in Selma to see which he liked. Late

period that plaintiff Duckworth applied for and was refused

an apartment at Les Chateaux (A. 60, 87).

10

in the evening they arrived at Les Chateaux and Houston, who

is white, got out of the automobile, approached Moore Sr., and

inquired whether he had any apartments (A. 140-141). An

appointment was made with Moore, Sr., to look at an apartment

the next day, since it was late and Duckworth was exhausted

(A. 141, 166). Houston advised the plaintiff he had made the

appointment and that he should go view the apartments. He did

not accompany Duckworth the following day as he considered his

duty as sponsor fulfilled when he located the apartment (A. 142).

Immediately after work the next day, July 8 , 1975, Duckworth

met Moore, Sr., who told him there were vacant apartments but

none was available to rent. Duckworth did not question the truth

of what Moore, Sr., told him and continued his search for housing

(A. 173).

After Duckworth had unsuccessfully searched for housing on

his own for approximately one week, he contacted the Housing

Referral Office at Craig Air Force Base in order to seek help

in obtaining an apartment, and spoke to Mrs. Shirley Crear, a

Housing Referral Officer (A. 160, 207).

The Housing Referral Office of Craig Air Force Base has the

responsibility to find housing for military and civilian personnel

(A. 119, 199-200). To fulfill that responsibility, officers,

including two women, Mrs. Crear and Mrs. Gamble, provide

information to new personnel concerning the community and housing,

11

confirm vacancies at particular apartment complexes, and attempt

to make appointments for unsettled personnel, like plaintiff

Duckworth (A. 119, 199-200). In the course of her duties, Mrs.

Gamble makes telephone calls to owners and managers of apartment

buildings in order to compile a current listing of vacant

apartments in Selma (A. 119). Records are regularly maintained

of such vacancies and kept up-to-date by all persons working

in the office (A. 125, 205-206). The vacancies or listings are

recorded in a flipex card file and are removed when they are no

longer available (A. 205).

When Duckworth asked on July 14, 1975 for further aid in

finding an apartment, Mrs. Crear reviewed the office's records

(A. 207). Those records indicated that as of July 11, 1975

3/

there were two vacancies at Les Chateaux (A. 206). Plaintiff

Duckworth told her that he had been to Les Chateaux several days

before and Moore, Sr. had told him there were no vacancies (A. 207)

Mrs. Crear assumed that the apartments at Les Chateaux

had become vacant after Duckworth's first attempt to secure

housing in that complex and she proceeded to call the defendant,

Moore, Sr., to verify the vacancies and to make an appointment

3/ It is undisputed that the records which were maintained by

the Housing Referral Office reflected the fact that as of July 11,

1975 there were two vacancies at Les Chateaux. Mrs. Gamble

testified that in the course of her responsibilities she telephoned

Moore, Sr., on July 11 to ask about available apartments; that Moore

Sr., had told her that he had tvo vacancies in the complex and that

she consequently wrote that information in the files (A. 123-125)

Moore, Sr. denied having this conversation (A. 82).

12

her inability to recall the conversation accurately, Mrs. Crear

read directly from her business records which she made at the

time she had the conversation with the defendant:

"8:45 on the 14th of July I called Mr. Moore

to see if he still had the two vacancies that

the Housing Referral Office had listed. He

was rather vague at first, stating that he had

several people looking at them. I stated that

I had an individual very much interested in

looking at one if he had one available. Mr.

Moore mentioned he would have it ready in a day

or two. He then asked if the individual had

pets. I stated, 'no.' He wanted to know if

the individual had children or a wife. I stated,

'no.' Mr. Moore then said if the individual wanted

to come down he would be glad to show the apartment

to him. An appointment was made for the following

afternoon at fifteen hundred. Mr. Moore said to

meet him at Apartment 8 , Les Chateaux. And this

was the apartment he was working on. I then told

Mr. Moore that Mr. Duckworth was the name of the

individual he would be expecting. Mr. Moore made

the comment, 'Mr. Duckworth? Hey, well tell Mr.

Duckworth I will take care of him. There are a

lot of pretty girls for him out here.' I confirmed

the time and place of the meeting again and told

Mr. Moore that Mr. Duckworth would be there" (A. 209-

210) .

Mrs. Crear testified that she told the defendant the plaintiff's

name but did not reveal his race as she was prohibited from doing

so by Federal regulations (A. 210).

Plaintiff Duckworth kept the appointment which Mrs. Crear

had made for him, but when he arrived at Apartment 8 at Les

4/

Chateaux, Moore, Sr., told him it was not for rent (A. 89, 175).

for Duckworth to visit the apartments (A. 208). Because of

4/ It is undisputed that defendant Moore, Sr. spoke to Mrs.

Crear, that he made the appointment, that he showed Apartment 8

to Duckworth, and that he told him it was not for rent (A. 89-90).

13

Plaintiff Duckworth returned to the Housing Referral Office

on July 16, 1975 and told Mrs. Crear he had again been denied

an apartment by defendant Moore, Sr. who insisted it was rented

(A. 215) .

While there were no vacancies at Les Chateaux for plaintiff

Duckworth, defendants had vacant and available apartments to rent

to white persons who inquired during the same period. in

addition to the fact that the Air Force Records of July 11 and

July 14 memorialized the statements by Moore, Sr., that there were

vacancies at Les Chateaux, the Air Force Base's records further

reflected that on July 12, four days after plaintiff's first

visit when he was told nothing was available and two days before

his second visit, Moore, Sr., showed and offered an apartment at

the complex to a white man from Craig Air Force Base, Lieutenant

Wells, who decided not to rent it (A. 213-215).

Defendants' purported explanation as to why they refused to

rent plaintiff Duckworth any of the three apartments, numbers 8,

34 and 41, vacant during the month of July when plaintiff Duckworth

sought housing, was that they were being "held" for other people

(A. 64, 79). Moore, Sr., testified, however, that he did not

collect deposits to hold the apartments in any of the three

instances (A. 72, 79). Moore, Sr. stated that he did not secure

or ever receive telephone numbers or addresses of any of these

other people (A. 75, 79). He even admitted that he had never met

and did not know the name of one of the people to whom he had "promised1

14

an apartment (A. 79). Not surprisingly, none of these people

contacted the defendants to obtain the apartments they had been

"promised," and none of them ultimately rented one (A. 80, 83, 296).

Moore, Sr., testified that he had held one of the apartments,

number 34, for Susan Ward Black (A. 72). Ms. Black requested

the defendant in the latter part of June, 1975 to hold an apart-

5/

ment (A. 293). As noted above, however, she left no deposit

and no address, and never contacted the defendant to tell him she

did not want the apartment (A. 296). Moore, Sr., testified that he

had volunteered to hold Apartment 41 for his niece, Becky Cooper

(A. 77). Ms. Cooper had earlier occupied Apartment 41, but had

vacated it and left Selma by the end of June, 1975 (A. 308).

Although Moore, Sr„ knew she was "quite uncertain" about returning,

he testified that he held it for her until August 1, 1975 when

he finally contacted her (A. 77). Ms. Cooper resumed residence in

Selma, but did not return to an apartment at Les Chateaux (A. 308-

309) .

Apartment number 8 at Les Chateaux was also vacant when

plaintiff Duckworth was refused housing. Moore, Sr., claimed that

defendant Welch asked him to hold the apartment for a "friend,"

and that he held it vacant for a month and a half even though he had

no idea as to the identity of the "friend" (A. 79). Although Welch

testified at trial, he did not corroborate Moore's testimony,

identify the mysterious person, or in any way support the contention

that he was responsible for keeping the apartment vacant.

5/ Moore, Sr., stated that he volunteered to hold it (A. 73).

15

Two of the three apartments, numbers 8 and 41, had been

vacant three weeks at the time plaintiff Duckworth first inquired

about housing at Les Chateaux and were vacant a full month at

the time of his second visit on July 14 (A. Ill, 112). The third

unit, apartment 34 had been vacant since the beginning of July

(A. 109). when Duckworth asked for an apartment on July 8 and 14,

1975, however, Moore testified he did not offer to call any of the

people for whom he was allegedly reserving the vacant apartments

to see if they still wanted them because Duckworth wanted the

apartment immediately and "there wasn't time enough to aggravate

those girls then" (A. 84, 85). Nevertheless, when a white

sergeant from Craig Air Force Base inquired at Les Chateaux about

an apartment and said he needed an apartment "at once," Moore, Sr.,

did offer to check with his niece to see if she was going to rent

a vacant apartment (A. 213-214).

Defendant Moore, Sr., could not recall, during the entire ten

years that he managed the complexes at issue, that he had ever held

apartments before for as long as he did during July, 1975 (A. 87).

When asked to explain why this sharp deviation from practice

occurred during the very same period that plaintiff Duckworth, a

black man, was seeking housing, the defendant's sole justification

was that "it is purely coincidental" (A. 87). it was also "purely

coincidental" that none of the three people rented the apartments

that were refused to Duckworth (A. 87).

16

Neither the Department of Defense nor plaintiff agreed that

the refusal of the defendants to rent Duckworth an apartment was

pure coincidence. On July 16, 1975, Duckworth returned to the

Housing Referral Office to inform Mrs. Crear that he had again

been denied an apartment, and filed a complaint. Pursuant to

Regulation, the Air Force Base conducted an investigation,

during which time Mrs. Crear, as an officer of the Housing Referral

Office, attempted to resolve the issue by speaking directly with

Moore, Sr. (A. 215). As part of the investigation, a white

sergeant volunteered to test the availability of apartments at

Les Chateaux in order to see if defendants were in fact reserving

apartments that they could not release or whether they were only

holding the apartments so that a black man could not have one.

As stated above, when this white sergeant inquired about an

apartment on July 17, 1975, Moore, Sr., readily volunteered to

attempt to make an apartment available (A. 242). The Department

of Defense found that defendants had refused to rent to Ray

Duckworth for racially discriminatory reasons and the Base Commander

of Craig Air Force Base imposed a restrictive sanction against

defendants for one hundred and eighty (180) days during which time

the Housing Referral Office and Air Force personnel were prohibited

from dealing with defendants (A. 230). At the request of the

United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, the

Base Commander extended the sanction for an additional ninety (90)

days (A. 236-237).

Plaintiff Duckworth eventually rented an apartment at another

complex, Candlewood, on approximately July 18 or 19, 1975

17

(A. 178) . As a result of defendants' refusal to rent him

any one of the at least three vacant apartments on July 8 and 14, 1975,

plaintiff Duckworth was forced to live in a motel for an addi

tional ten days. In addition, as a young stranger to Selma,

Duckworth suffered embarrassment and humilation by being the

subject of discrimination and by knowing that his co-workers at

the Air Force Base knew he had been victimized (A. 192).

B . Other Evidence Adduced At Trial

According to the undisputed facts and defendants' own testi

mony, plaintiff Duckworth was refused an apartment when three were

vacant and unleased for substantial periods of time on the basis

of a policy that for an entire decade was instituted only once,

during the time that Duckworth applied for housing in an all-white

apartment complex. This unique institution of a policy which

prevented a black from obtaining housing in itself unlawfully dis

criminated against plaintiff Duckworth. The overwhelming weight

of evidence at trial demonstrated further that those apartments,

while always vacant, immediately became unavailable only when

plaintiff Duckworth appeared at Les Chateaux.

As noted earlier, Randy Houston, Duckworth's sponsor at Craig

Air Force Base, initiated the first contact with Moore, Sr. on

the plaintiff's behalf. Houston testified that when he asked the

18

defendant' on July 7, 1975 if there were any available apartments,

Moore, Sr., said, "Yes, he had a couple of apartments for rent"

(A. 141). Duckworth was told there were no apartments the

next day. Moore said that he told Houston that "he had two

vacant furnished apartments, 34 and 31 [sic] [but] neither one

was available" (A. 64) .

An officer at the Air Force Housing Referral Office, Mrs.

Gamble, testified that Moore also told her on July 11, 1975 he

had two vacancies at Les Chateaux (A. 124) . On cross-examination,

counsel for defendants made the incredible semantic argument that

§/Moore meant he had two vacancies but none were available (A. 125).

Mrs. Crear, another Housing Referral Officer, was also told

there were available apartments. When Mrs. Crear telephoned

Moore, Sr., on July 14, she testified that the defendant said "he

was in the process of cleaning one up and would have it ready in

a day or two,"and that it was available for rent (A. 209-210).

When plaintiff Duckworth visited the complex the same day, defend

ant told him there was nothing available (A. 175). Moore,

Sr., admitted saying he had vacant apartments, but again denied

saying they were available (A. 81). Three white disinterested

6/ Moore denied talking to Mrs. Gamble at all, but, of course,

could not explain why the Air Force records of July 11 reflected

the fact that the conversation had occurred (A. 82).

19

witnesses stated that Moore offered apartments as available for

rent shortly before and after Duckworth's first visit to Les

Chateaux, and, indeed, on the same day the plaintiff made his

second inquiry at the apartment complex. The only witness at

trial who testified of being told by defendant Moore, Sr., that

there were no available apartments was plaintiff Duckworth.

20

ARGUMENT

I.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE TO PLAINTIFF'S

PRIMA FACIE CASE OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION

WAS INADEQUATE, AS A MATTER OF LAW, AND

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN NOT GRANTING

PLAINTIFF'S MOTIONS FOR A DIRECTED VER

DICT AND JUDGMENT NOTWITHSTANDING THE

VERDICT. IN THE ALTERNATIVE, THE VERDICT

WAS CLEARLY AGAINST THE WEIGHT OF THE

EVIDENCE AND, AT THE VERY LEAST,' THE DISTRICT

COURT ERRED IN NOT GRANTING PLAINTIFF’S

MOTION FOR A NEW TRIAL.

The standard applied to both a motion for a directed

verdict and a motion for judgment notwithstanding the

verdict is the same. In each instance, a court is required

'to decide, whether, as a matter of law, the

evidence, when considered in the light most

favorable to the non-moving party, is legally

sufficient to submit the case to the jury, or

whether it is legally sufficient to support

the jury's verdict.' Urti v. Transport Com

mercial Corporation, 479 F.2d 766 (5th cir.

1973).

Spurlin v. General Motors Corp., 528 F.2d 612, 616 (5th Cir

1976); Glazer v, Glazer. 374 F.2d 390, 400; 6A Moore's

Federal Practice 559.08 [5] at pp. 59-152 (1972). These

motions are analogous to a motion for summary judgment; if

persons might differ as to the reasonable legitimate con

clusions of fact to be drawn from the evidence the motions

must be denied. Urti v. Transport Commercial corp.,

supra; McPherson v. Tamiami Trail Tours, Inc., 383 F.2d 527

21

528 (5th Cir. 1967); see Nesbith v. Alford, 318 F.2d 110,

123 (5th Cir. 1963); Bullock v. Tamiami Trial Tours, Inc..

266 F.2d 326, 330 (5th Cir. 1959). In ruling on a motion

for a new trial, however, the issue is whether "the verdict

is against the clear weight of the evidence . . . or will

result in a miscarriage of justice." united States v. Bucon

Construction Co.. 430 F.2d 420, 423 (5th Cir. 1970); accord,

Massey v. Gulf Oil Corp.. 508 F.2d 92, 94 (5th Cir. 1975);

United Broadcasting Co. v. Armes, 506 F.2d 766 (5th Cir. 1975).

A district court's grant or denial of such a motion is within

its discretion, and is reviewable only for an abuse of that

discretion. Spurling v. General Motors corp., supra. A

review of the evidence reveals an unrebutted case of racial

discrimination requiring a judgment for plaintiff as a

matter of law. At the very least, the judgment was against

the "clear weight of the evidence" and, if not vacated by

this Court, will result in a great "miscarriage of justice."

In cases involving racial discrimination in housing,

courts have heeded the well-recognized principle that "sta

tistics often tell much and courts listen." State of Alabama

v. United States. 304 F.2d 583 (5th Cir. 1962), aff'd, 371

U.S. 37 (1962). See United States v. Youritan Construction

Company. 370 F. Supp. 643 (N.D. Cal. 1973), aff'd. 509 F.2d

623 (9th Cir. 1975); United States v. Northside Realty

Associates, Inc., 518 F.2d 884, 888 (5th Cir. 1975); Williams

v. Matthews, 499 F.2d 819, 827 (8th Cir. 1974); United States

22

v. Reddoch, 467 F.2d 897 (5th Cir. 1972); United States

v. Real Estate Development corp.. 347 F. Supp. 776, 782

(N.D. Miss. 1972); Newbern v. Lake Lorelei, Inc., 308 F.

Supp. 407, 411 (S.D. Ohio 1963).

Defendants here operated two apartment complexes which

together contained 78 units. The apartments were located in

a county with a population 52% black, yet not a single

unit in either complex had ever housed a black tenant (A. 45,

91). Racial underrepresentation in housing is always telling,

but "[njothing is as emphatic as zero." United States v.

Hinds County Board of Education, 417 F.2d 852, 858 (5th Cir.

1969). In United States v. Reddoch, supra, this court

emphasized that there had "never been any black tenants in

the complex during the three years of its operations." in

this case, River Oaks and Les chateaux had been operating

seven and ten years, respectively (A. 48).

As the district court recognized, such statistics,

coupled with the rejection of a black applicant for a vacant

dwelling, have been held to constitute a prima facie case of

discrimination, casting the burden upon defendants to come

forward with evidence to the contrary. United States v .

Youritan Construction Co., supra, 370 F. Supp. at 649;

Williams v. Matthews, supra, 499 F.2d at 827; United States

v. Reddoch, supra; United States v. Real Estate Development

23

Corp., supra? Newbern v. Lake Lorelei, Inc., supra.

Not only did defendants fail to come forward with

sufficient evidence to explain their refusal to rent

plaintiff Duckworth any one of three vacant apartments at

Les Chateaux? they presented not a single legitimate

justification for their actions.

It was undisputed that Les chateaux had three vacant

apartments at the time Duckworth first sought housing there on

July 8, 1975, and when he returned on July 14, 1975

(A. 48). Moore, Sr.'s sole explanation for the refusal to

rent these apartments was that they had been promised to

three separate groups of persons (A. 64, 79). Assuming ,

for the purposes of the subject motions, that those promises

were in fact made, the consistent practice employed by Moore,

Sr., during the ten years he had managed Les Chateaux and

River Oaks, was to seldom make such promises, and if made

at all, to honor them for 3-4 days or a week at the most

(A. 62-63). When Duckworth first applied, two of the vacant

apartments, numbers 8 and 41, had been vacant three weeks?

number 34 had been vacant 8 days. By plaintiff's second

attempt to secure housing, numbers 8 and 41 had been unoccupied

for an entire month (A. 70, 111, 112).

Defendants’ unprecedented departure from a ten-year policy to

prevent Duckworth from obtaining housing cannot as a matter

of law be justified by Moore, Sr.'s protestations of mere

24

"coincidence" (A. 87). Moore, Sr.'s alleged desire to

keep his word to hold an apartment yielded to the business necessity

of renting vacant apartments after a week in all instances

except when faced with a black applicant. The promise

dissipated when two white persons made applications vir

tually simultaneously with Duckworth. On July 8, 1975,

Moore, Sr., told Duckworth there were no vacancies (A. 173).

However, when a white Lieutenant applied on July 12, 1975,

Moore, Sr., offered him and his wife an apartment (A. 213-

215). The Lieutenant declined to take the apartment on

July 14, but when Duckworth returned that same day to Les

Chateaux, Moore, Sr., again insisted there were no apart

ments available for him (A. 89, 175). Moore, Sr., alleged

desire to keep his promises also evaporated when a white

sergeant, who volunteered to test the complex, inquired

about an apartment at Les Chateaux on July 16, just two days

Uafter Duckworth's second visit. Moore, Sr., volunteered

2/ It is established law in housing discrimination cases

that the experience of testers is competent evidence to

prove that a defendant has engaged in unlawful conduct.

jE.c[., Zuch v. Hussey, 394 F. Supp. 1028, 1051 (E.D. Mich.

1975), aff*d 547 F.2d 1168 (6th Cir. 1977); United States

v. Youritan Construction Co., supra; Johnson v. Jerry Pals

Real Estate, 485 F.2d 528 (7th Cir. 1973); Williamson v.

Hampton Management Co., 339 F. Supp. 1146 (N.D. 111. 1972).

25

to try to make one of the "promised" apartments available

as soon as possible although, of course, no such offer

had been extended to Duckworth (A. 242) . As one court

observed, "defendants' conduct was inconsistent with any

intent to enforce the policy in a nondiscriminatory way

or, indeed, to enforce the policy at all except against

plaintiff." Williamson v. Hampton Management Co., supra,

339 F. Supp. at 1148.

Not only did defendants offer to whites the same

apartments they refused to Duckworth, a black man, their

excuse — that they had "promised" the apartments — was

the type of sharp, indeed unique, departure from the usual

course of business that courts have held to be violative

of the fair housing laws, for the imposition of conditions

on blacks which are not made on whites deprive persons

like Duckworth of "the equal right" to housing guaranteed

by law. Seaton v. Sky Realty Co.. 491 F.2d 634, 636 (7th

Cir. 1976); United States v. Mintzes, 304 F. Supp. 1305

(D. Md. 1969); Banks v. Perks, 341 F. Supp. 1175 (N.D.

Ohio 197 2) .

Moreover, the total lack of procedures to reserve

vacant apartments was hardly, as this Court observed in an

analogous context, "consistent with common sense or ordinary

26

business practices." United States v. Pelzer, supra, 494

F.2d at 446. Defendant's refusal to rent apartments they

were allegedly holding for persons who left no forwarding

address, telephone number or deposit is so informal as to

8/be inherently "fraught with racial overtones."- Williams

v. Matthews, supra, 499 F.2d at 828; see Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1970). Indeed, Moore, Sr.

never even knew the name of the person who had "reserved"

Apartment 8. At one point, the defendant explained his

failure to request and obtain deposits for the three

apartments by stating deposits were not required to hold

apartments at the time Duckworth applied (A. 320-321), but

he quickly changed his testimony to admit that deposits were

necessary, and the documentary evidence confirmed this was

the case. Defendant read from a deposit slip for Apartment

48 that established it was leased July 15, 1975, but a

deposit made by the same tenant was dated July 7, 1975

(A. 327). Because the fair housing laws prohibit "sophis

ticated as well as simple-minded" forms of discrimination,

8_/ Nor can defendant's affirmation of good faith or mere

denial of discrimination serve to rebut the evidence of

racial discrimination. Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S.

625, 632 (1972); Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346, 361 (1970);

Sims v. Georgia, 389 U.S. 404, 407 (1967); Williams v.

Matthews, supra, 499 F.2d at 827. As this Court has held,

the assertion that a procedure "was not conceived out of

racial discrimination is of no avail, since [it] was

administered in a discriminatory manner." United States v.

West Peachtree Tenth Corp., 437 F.2d 221, 228 (5th Cir. 1971).

27

disparity of treatment, tactics of hindrance, isolated

departures from policy, and special treatment "must receive

short shrift from the courts." Williams v. Matthews, supra,

499 F.2d at 826, see United States v. Youritan Construction

Co., supra. Defendants' unique treatment concerning the

vacant apartments Duckworth sought deserves no more than

the "short shrift" accorded other forms of discrimination.

In sum, a careful view of the entire record establishes

uncontradicted proof of discrimination on not one, but several

grounds. The absolute absence of any black tenants at Les

Chateaux, the unique and drastic departure from the usual

policy of reserving apartments during the moment of

plaintiff's two applications, the informal, subjective rental

process and the disparate treatment accorded plaintiff

Duckworth and white applicants during the same week decis

ively and inescapably establish proof of racial discrimina-

9/tion.~ Mere verbal denials by defendants cannot alter the

conclusion that they in fact unlawfully discriminated on

the basis of race. Even in light of the applicable

_9/ Indeed, the Department of Defense after a thorough

investigation concluded that defendants had racially

discriminated against Duckworth and imposed a 180 day

sanction oa the defendants (A. 230). The United States

Department of Housing and Urban Development agreed with the

conclusion that Duckworth had been discriminated against

and requested that the 180 day sanction be extended an

additional 90 days. The Department of Defense complied with

that request (A. 236-237).

28

standards of review,

"When the facts — clear and uncontradicted

as they are here — show without doubt

whatsoever that there was not a single basis

for [the outcome], neither those facts nor

the inferences to be drawn from them are

changed in any degree by [the] jury verdict

. . . which ought never to have been dis

missed . . . as the law so positively required."

Nesbith v. Alford, supra, 318 F.2d at 123.

To permit the jurv verdict to stand "would be to encourage

real estate agents to avoid selling [or renting] white

properties to blacks, despite the clear Congressional mandate

to the contrary." Johnson v. Jerry Pals Real Estate, 485

F.2d 528, 531 (7th Cir. 1973); see Smith v. Adler, 436 F.2d

344 (7th Cir. 1971); Haythe v. Decker Realty Co., 468 F.2d

336 (7th Cir. 1972); United States v. Real Estate Development

Corp., supra, 347 F. Supp. at 781-783. Contract Buyers1

Leauqe v. F & F Invest. Co., 300 F.Supp. 210 (N.D. 111. 1969),

aff'd, 420 F .2d 1191 (7th Cir.1970).

Argument

II.

DEFENDANTS 1 LEASING PRACTICES

CLEARLY ARE INTENDED AND HAVE

THE EFFECT OF DISCRIMINATING

AGAINST BLACKS GENERALLY AND

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN

NOT AFFORDING THE PLAINTIFF

CLASS PROSPECTIVE COMPREHEN

SIVE INJUNCTIVE RELIEF.

Prior to trial, the district court ordered the case to

proceed as a class action for the purposes of injunctive

relief. (A.15) In light of the clear pattern of discrimina

tory leasing practices resulting in the total exclusion of

blacks from defendants' complexes, the district court erred

10/

in denying prospective injunctive relief.

As noted above, in the ten years that Les Chateaux and

in the seven years that River Oaks operated, not one of

defendants 1 78 units had ever been leased to a black person,

despite an area population that was 52% black. (A.45,91)

Several of defendants1 practices contribute to this result.

First,defendants considered an applicant on the basis

of whether he would be compatible with then current tenants.

When all of the tenants are white "to consider the prospective

acceptance of an applicant by current tenants as a significant

factor in passing on his application tends to operate against

10/ The right of the plaintiff class to relief is not

dependent upon the outcome of Duckworth's claim. Huff

y* N.P. Cass Co, of Alabama. 485 F.2d 710 (5th Cir. 1973)

kgjjjg )» Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co.. 457 F.2d 1377, 1380, cited with approval in Franks v. Bowman.

---.U.S.--- , 47 L.Ed. 2d at 456, n.7 (1976); Parham v.

Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 433 F.2d 421, 478 (8th Cir.

1970); Cf. Jenkins v. Union Gas Corp.. 400 F.2d 28 (5th Cir.1968).

30

a black applicant and to promote the continued all white

character of the complex." United States v. Reddoch,

supra, Prentice-Hall Equal Opportunity in Housing Reporter,

•113,569. (See A.217)

Secondly, defendants had virtually no objective standards

for selecting tenants. In the absence of objective standards,

subjective determinations albeit neutral on their face are

indicative of racial discrimination. Smith v. Sol Adler

Realty Co., 436 F.2d 344 (7th Cir. 1971); Williamson v.

Hampton Management Co., supra, 339 F.Supp at 1148. See,

ii_/

Rowe v. General Motors, 457 F.2d 348, 354 (5th Cir. 1972).

An applicant's only requirement was that he meet Moore, Sr.,

in a face-to-face interview so that the defendant could see

if the applicant "looks decent" (A. 57-58, 60). The

defendant approved applicants who would "fit in" with other

tenants (A.217). Such a compatibility standard should be

carefully scrutinized in apartment rental cases. United

States v. Youritan Construction Co., supra, 370 F.Supp. at

650. The subjective selection process in this case produced

two apartment complexes which were consistently all-white for

ten years (A.45, 91). Just as vague employment standards

which result in whites, but not blacks, being hired are un

lawfully discriminatory "so too are arbitrary apartment rental

11_/ The use of subjective criteria in race matters has been

uniformly rejected or limited in other areas of civil rights.

E.g., McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1972)

(employment); Singleton v. Jackson Mun. Sep. School District,

419 F .2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1970), cert, den., 396 U.S. 1032 (1971)

(hiring) and firing of teachers in systems undergoing desegrega

tion process); Smith v. Concordia Parish Sch. Bd., 445 F.2d

285 (5th Cir. 1971)(reduction of staff in school desegregation

process).

31

procedures which produce otherwise unexplained racially

discriminatory results." United States v. Youritan Construction

Co., supra, 370 F.Supp. at 640-650; Williams v. Matthews, supra;

370 F.Supp. at 640-650; Williams v. Matthews, supra; see, £.£.

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Mach. Co., 457 F.2d 1377, 1383

(4th Cir. 1972), cert, den., 409 U.S. 982 (1972) (employment).

The testimony of Mrs. Crear, an officer at the Housing

Referral Base at Craig Air Force Base shed light on the actual

reason and effect of defendants' subjective procedures.

Duckworth had been twice refused an apartment at Les Chateaux

and, in disgust, had filed a complaint of racial discrimination.

Mrs. Crear then telephoned Moore, Sr., to determine if he in

fact had vacancies. Mrs. Crear testified that during the

conversation:

"Mr. Moore went on to say that he prefers

couples and tries to pick tenants that

would fit in . . . Mr. Moore then mentioned

a Wop family that inquired about an apart

ment and he felt they would not be suitable

tenants. After inquiring as to what it

meant and being told it meant a Puerto Rican

. . . Mr. Moore stated that it was the way

that they were dressed and that they were

not clean and he felt they would not keep

a clean apartment" (A.217).

Moore, Sr., could not recall having had this conversation

(A.87).

The statistical evidence and subjective application

procedures, as well as Duckworth's experience, overwhelmingly

testify to class-wide discrimination that can be remedied only

through injunctive relief. On remand, the district court must

32

fashion such relief guided by the decree appended to

U .S. v. West Peachtree Tenth Corp., 437 F.2d at 229.

(See, in particular, requirement that "written objective

non-racial criteria" be developed, 437 F.2d at 230.)

33

Ill

DEFENDANTS MOORE, JR., AND WELCH, AS

OWNERS AND PRINCIPALS OF LES CHATEAUX

AND RIVER OAKS, ARE LEGALLY LIABLE FOR

THE DISCRIMINATORY CONDUCT OF THEIR

AGENT.

A. The District Court Erred in Granting A

Directed Verdict and Dismissing the

Complaint Against The Apartment Complex

Owners.__________________________________

Defendant William B. Moore, Jr., and Harry Welch are

the principals and owners of both Les Chageaux and River

Oaks apartment complexes (A. 104, 273). In the Pre-Trial

Order, as well as during trial, defendants stipulated that

William B. Moore, Sr., is the rental agent for Les Chateaux

apartment complex and, at all times material, acted within

the line and scope of his authority as such rental agent

(A. 16, 253). For performing services as managing and

rental agent of Les Chateaux and River Oaks, Moore, Sr.,

receives a salary (A.13).

It is plainly established under the Fair Housing Laws

that principals are liable for the discriminatory actions of

their agents under the doctrine of respondeat superior and

because the legal duty to obey the law is non-delegable.

United States v. Youritan Construction Co., supra, 509 F.2d

at 647; Moore v. Townsend, 525 F.2d 482 (7th Cir. 1975) Marr v.

Rife, 503 F.2d 735, 741-2 (6th Cir. 1974); United States v.

34

Northside Realty, supra, 474 F.2d at 1168; United States

v. Reddoch, supra; United States v. L & H Land Corp., Inc.,

407 F. Supp. 576, 580 (S.D. Fla. 1976); United States v.

Berg Enterprises, Prentice-Hall Equal Opportunity in

Housing Reporter, 5 13,773 (S.D. Fla. 1976); Lyles v.

Hampton, Prentice-Hall Equal Opportunity in Housing

Reporter, f 13, 738 (S.D. Ohio 1975); United States v.

Real Estate Development Corp., 347 F. Supp. 776, 785 (N.D.

Miss. 1972); Williamson v. Hampton Management Co., supra;

United States v. Mitchell, 335 F.Supp. 1004, 1006 (N.D. Ga.

1971) Indeed, the district judge agreed with the state

ment of the law that:

the discriminatory conduct by an

apartment manager, rental agent,

or other individual acting in a

representative capacity is attrib

utable to the owner, manager, or

other principal, both under the

doctrine of respondeat superior

and because the duty to obey the

law is non-delegable. (A. 38).

However, at the close of the testimony and before the

case was submitted to the jury, the district court relieved

the principals Moore, Jr., and Welch from any liability on

the grounds that there was no "willful participation" by

the principals in the discriminatory conduct; there was no

evidence that they "ratified his actions;" and because Moore, Jr.

testified he had instructed his agent about the Fair Housing

35 -

Laws (A. 336-337). This decision was error.

Numerous courts have specifically held principals

liable for their agents1 discriminatory conduct regard

less of the principals' personal behavior. The Court

of Appeals in Marr v. Rife, supra, 503 F.2d at 742 held:

"While the evidence does not indicate

that Arntz acted with the approval or

at the direction of appellee Rife, we

do not believe that such a finding is

necessary to hold Rife liable. As owner

. . . Rife had at least the power to

control the acts of salesmen. Rife would,

therefore, be liable for compensatory

damages. . . ."

12/

12/ In the order by which the district court denied the

motions of plaintiff for judgment notwithstanding the verdict

or for a new trial, the court adhered to its decision to

grant a directed verdict for the principals, relying on

United States v. Reddoch, supra, and United States v. Real

Estate Development Corp., supra, to support his view that

unless there was evidence that the owners had given racially

discriminatory instructions to their agents or had them

selves personally engaged in racial discrimination prior to

1968 and had failed to advise their agents of a change in

policy, no liability attached (A. 40). However, in United

States v. Reddoch, the issue of the principal's liability

for the actions of his agent, as distinct from his own

actions, was not specifically addressed; and in United

States v. Real Estate Development Corp., the court held:

"The resident managers and managers of the defendants, as

agents of the defendants, are authorized to represent the

defendants and can rent in no other capacity. Their acts

and statements made within the scope of their agency, are

attributable to the defendants whose duty to comply with the

law is non-delegable." 347 F.Supp. at 785. The failure

of the defendant affirmatively to advise the agent of any change in rental practices after passage of the 1968 Fair

Housing Act was not relied on by the court to justify a

finding of liability, but merely to satisfy the pattern

and practice requirement of 42 U.S.C. §3613. id. at 784.

36

This Court in United States v. Northside Realty, supra,

474 F.2d at 1168, also held the corporate defendant principal

liable because the manager's action inured to the benefit

of the principal, although the principal there did not

directly supervise the agent. This is obviously the

situation in the instant case. In addition, in

United States v. Bob Lawrence Realty, 474 F.2d 115 (5th Cir.

1973) this Court held the principal liable for the conduct

of its sales agents despite evidence to the effect that it

took affirmative action to ensure compliance with the Fair

Housing Act. Accord, United States v. Mitchell, supra;

United States v. Youritan Construction Co., supra.

The law could not be otherwise. The Nation's fair

housing laws are to be liberally construed to achieve our commit

ment to open housing. United States v. Bob-Lawrence Realty,

474 F.2d 115 (5th Cir. 1973). Sullivan v. Little Hunting

Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229, 239 (1969)(all "necessary and

appropriate remedies" are to be afforded in §1982 action).

If principals and owners of apartment houses were allowed

to insulate themselves from liability by ignoring the rental

practices over which they have ultimate control, innumerable

instances and practices of blatant discrimination against

blacks would persist and remain unremedied. Indeed, in

this very case, Moore, Sr. was allowed to perpetuate two

13/

apartment complexes as exclusively white for ten years.

13/ As noted above in Pt.l, supra, defendants' rental

procedures were totally informal and subjective. Owners are

liable for failing to set forth objective and reviewable pro

cedures for apartment application and rejection. United States

v. Youritan Construction Co., supra.

_ 37 _

It follows that to suggest that Moore, Jr., and Welch

should not be held accountable for the blatant discrima-

tion suffered by plaintiff Duckworth and members of

plaintiff class would be to ignore settled agency

principles and the policy objectives of the fair housing

laws.

The district court also erred in refusing to allow

the jury to consider the issue of liability for punitive

damages as to defendants Moore, Jr., and Welch.

Punitive damages are properly awardable in § 1982

actions. See, Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp., 429 F.2d

290 (5th Cir. 1970); Wright v. Kaine Realty, 352 F.Supp.

222 (N.D. 111. 1972). In Adickes v. Kress & Co., 398 U.S.

144, 188, the Supreme Court articulated the standard for

determining whether punitive damages should be awarded in

a civil rights action, and held that plaintiff "need not

show that the defendant specifically intended to deprive

14/

him of a federally recognized right." The Supreme Court

expressed the view that one who discriminated on the basis of

race after authoritative enactment of recent civil rights acts

must be said to do so "with reckless disregard as a matter of

law" and therefore may be found liable for punitive damages.

That Moore, Jr. and Welch allowed the total exclusion of

blacks from their apartment complexes for ten years and for

14/ This standard, expressed in an action brought under 42

U.S.C. §1983, is equally applicable to cases arising under

42 U.S.C. § 1982. See Lee v. Southern Homes Sites Corp., supra.

- 38

seven years after the passage of the Fair Housing Title

of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, could lawfully result in a jury

award of punitive damages regardless of whether defendant-principals

'specifically instructed their rental agent to discriminate.

In Hughes v. Dyer, 378 F.Supp. 1305, 1311 (w.D.

Mo. 1974), the Court reminds us that the critical function

of punitive damages is to "carry a message to all persons

subject to the command of §1982" that racial discrimination

in housing will not be tolerated. The Fair Housing Act

of 1968 and §1982 (Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, supra),

recognize the need for a deterrent through awards of punitive

damages. And the district court erred in not awarding them

here or, at the very least, in precluding such an award by

the trier of fact.

B. The Erroneous Dismissal of the

Principals So Prejudiced the

Plaintiff's Case As to Necessi

tate A Redetermination of Lia-

bility For All Defendants._____

The uncontradicted evidence establishes as a matter

of law that Duckworth was refused an apartment as a result

of defendant's unlawful discrimination. See Point 1,

supra. Reversal of the determination below is mandated

not only as to the manager Moore, Sr., but as to the other

defendants, Moore, Jr., and Welch, who are liable for the

- 39

discriminatory conduct of their agent. Supra, pp. 3 4-3 8.

In the alternative, denial of plaintiff's motion for a

new trial must be reversed because the erroneous

dismissal of the case as to Moore, Jr., and Welch preju

diced and tainted the jury's verdict as to Moore, Sr.

Moore, Sr., the sole defendant against whom the case

proceeded, is an 80 year old white man who has lived in Dallas

County since 1928 (A. 47). He is hard of hearing,

and a diabetic (A. 47, 68), and the agent's fragile

constitution was specifically pointed out to the jury: in

response to one question put forth by counsel for plaintiff,

Moore, Sr., responded, "I am a diabetic, and by George, when

I run out of steam I got to go to get something to eat"

(A. 68).

The jury had no opportunity to determine the liability of

the owners. In light of the evidence that Moore, Sr., frequently

spoke with his son and with Welch on occasion (A.116, 283, 324),

the jury might well have determined that the principals should

have exercised greater control over the elderly manager and that the

owners, or that all three defendants, not the agent alone, were

1S_/ Indeed, the law so mandates. See United States v. Youritan Construction Co., supra. ' --------

40 -

liable for the racial discrimination against plaintiff Duckworth.

At the very least, a new trial as to all defendants is necessary

to resolve that ambiguity.

IV.

THE JURY INSTRUCTION ON BURDEN OF

PROOF MISSTATED THE LAW AND REQUIRES

REVERSAL OF THE CASE

At the close of the trial, the district court proceeded to

instruct the jury as to the legal standards by which they were

to determine liability. Judge Hand stated:

"Now, there are three essential elements

of this cause of action. The first of these

is that the plaintiff offered or attempted

to lease the apartment described in the

evidence from the defendant, and was ready,

willing and able to pay to the defendant his

asking price.

Second, that the defendant refused to lease

the apartment at that price to the plaintiff.

And, third, that the effective reason for

the defendant's refusal was the race of the

plaintiff.

The plaintiff has the burden, as I have

indicated, of proving each of these essential

elements by a preponderence of the evidence.

And, if you find that each of these elements

is established, then you will find for the

plaintiff. if, however, you find that any one

of these elements has not been so established,

then you will find for the defendant." (A. 351).

At the close of the instructions, counsel for plaintiff objected

to this portion of the charge (A. 359-360). The jury instruction

misstated the law and necessitates reversal of the case.

41

It is clear that in order to establish a violation of

the Fair Housing Laws, the plaintiff need prove only that race

was any, or a significant, factor in the defendant's refusal to

rent. Moore v. Townsend, supra, 525 F.2d at 485; United States

v. Pelzer Realty, supra. There is a distinct and crucial

difference between the meaning of "effective" and "significant*"

16/

"effective" means "producing a decision" while a "significant"

factor means one among possibly many. Thus, the jury was

instructed, contrary to the law of this Circuit, that the race

of the plaintiff had to be the decisive factor. The giving of

this erroneous instruction mandates reversal. Burris v. Wilkins,

544 F.2d 891 (5th Cir. 1977).

The district judge also refused to give an instruction as

to the plaintiff's proof of a prima facie case and the consequent

burden of the defendant to overcome the presumption of discrimi

nation by a legitimate justification of their conduct. As the

district court recognized, the statistical proof coupled with

the refusal to rent a vacant apartment to a black person constituted

a prima facie case of discrimination which shifted the burden

to the defendant to prove to the contrary. United States v.

Youritan Construction Co., supra. 370 F. Supp. at 649; Williams

v. Matthews, supra, 499 F.2d at 827; United States v. Reddoch,

supra; United States v. Real Estate Development Corp., supra;

16/ Webster's New International Dictionary, 819 (2d ed.).

- 42

Newbern v. Lake Lorelei, Inc., supra (A. 335-336). The lack

of instructions on the established law left the jury without

"sound legal principles" to guide their determination. Albermarle

Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 416 (1975).

CONCLUSION

As this Court, other circuit courts and the Supreme Court

have recognized, the fair housing laws are the critical vehicle

for removing the scourge of slavery and for securing the equal

right to rent housing for all persons, whatever the color of

their skin. In light of overwhelming, uncontradicted, and un

rebutted evidence of racial discrimination in this case, exculpation

of defendants would flaunt the constitutional and public policy

goals of these laws. Owners and principals of housing cannot

be allowed to escape liability for systematic, blatant racial

discrimination in the rental of their apartments. Moreover,

instructions to jurors must make clear that the law prohibits

.asthe consideration of race/of any significance in apartmental

rental decisions.

For the foregoing reasons the district court's denial of the

plaintiff's motions for a directed verdict, for judgment notwith

standing the verdict, or, in the alternative, for a new trial

must be reversed.

- 43 -

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

BETH J. LIEF

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ROSE MARY SANDERS

Post Office Box 773

Selma, Alabama 36701

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned certifies that copies of the foregoing

brief of Plaintiff-Appellant Ray C. Duckworth was served by

United States mail, postage prepaid, this of May, 1977- 4 •

as follows:

James W. Garrett, Jr., Esq.

Post Office Box 270

Montgomery, Alabama 36101

Counsel for Defendants-Appellees

William B. Moore, Harry Welch,

and William B. Moore, Jr.

BETH J. 'LIEF

Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellant

44