Order for All Counsel Meeting

Public Court Documents

January 13, 1975

3 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Order for All Counsel Meeting, 1975. 8d0bbc4a-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3f08c92e-57eb-49f7-9cd0-89e6e71cd3d9/order-for-all-counsel-meeting. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

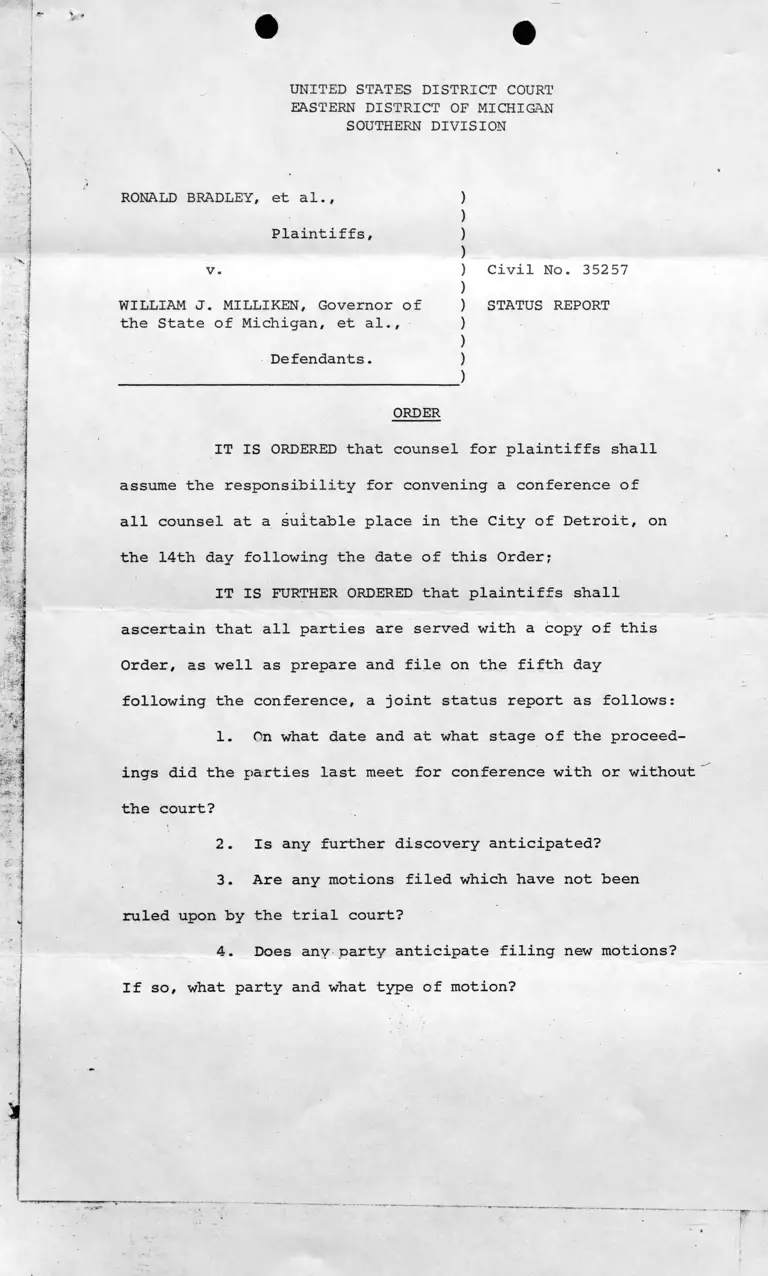

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.f )

)

Plaintiffs, )

)

v. )

)

WILLIAM J. MILLIKEN, Governor of )

the State of Michigan, et al., )

)

Defendants. )

_________________________________________________________ )

ORDER

IT IS ORDERED that counsel for plaintiffs shall

assume the responsibility for convening a conference of

all counsel at a suitable place in the City of Detroit, on

the 14th day following the date of this Order;

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that plaintiffs shall

ascertain that all parties are served with a copy of this

Order, as well as prepare and file on the fifth day

following the conference, a joint status report as follows:

1. On what date and at what stage of the proceed

ings did the parties last meet for conference with or without

the court?

*

2. Is any further discovery anticipated?

3. Are any motions filed which have not been

ruled upon by the trial court?

4. Does any party anticipate filing new motions?

Civil No. 35257

STATUS REPORT

If so, what party and what type of motion?

5. Which parties have intervened in this

action? On what date was intervention granted?

6. Are all of the intervening defendants

still parties to this lawsuit?

7. Which orders of the trial court, if any,

are still viable?

8. Are any proposed desegration plans hereto

fore submitted to the trial court still viable? If so,

summarize the positive and negative aspects of each plan.

9. Does any party intend to submit a new plan(s)

for desegregation? If so, what party and when?

10. Is any party presently developing a current

desegration plan(s) for the court's consideration?

11. If Question 10 is answered affirmatively,

what party? Are there objections to the plan?

12. Have the parties at any time concurred in

a plan for desegration?

13. Would a pre-trial at this time serve a

useful purpose? What date would the parties suggest for

ordering a pre-trial?

*

14. If a pre-trial is ordered by the court

pursuant to Rule XI of the local rules for the U. S.

District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan,

which orders, portions of the transcript, etc., should

be given priority by the trial court in preparing for the

pre-trial?

- 2 -

15. Please attach a bibliography of authorities,

including law review articles, books and other materials

critiquing desegregation plans implements! in sim:nar

*

cases.

Dated: January 13. 1975

*This report when prepared by plaintiffs' counsel shall:

(a) Follow the same numerical sequence contained in this

order.

(b) Represent the response agreed upon by all parties.

If any party is unable to agree to the response, that party

shall be identified and answer separately.

(c) Repeat the question so the court need not refer to

more than one document.

- 3-