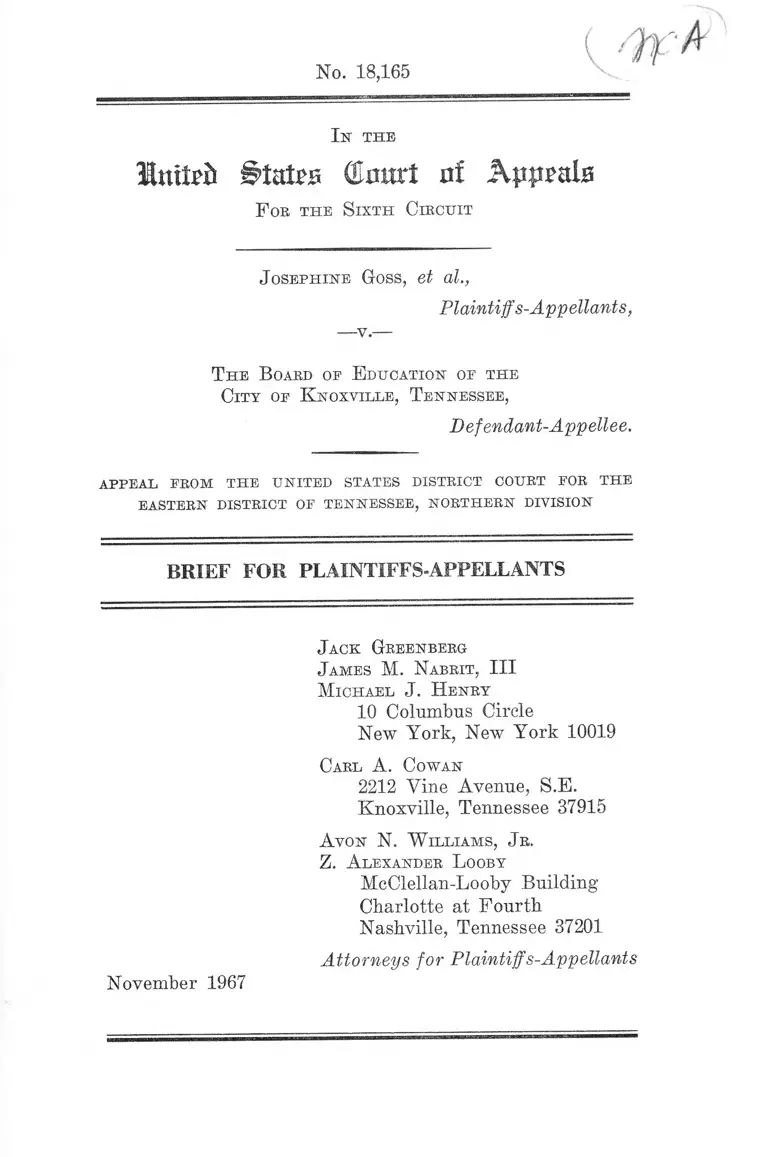

Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

November 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1967. c755b5f6-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3f25dd57-cb6e-4880-b987-a48317cc87e7/goss-v-knoxville-tn-board-of-education-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 18,165

In t h e

Itttoit §tatrs (Umtrt a! Appeals

F ob t h e S ix th C ibchit

J o seph in e G oss, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

— v .—

T h e B oaed of E ducation of t h e

C ity of K noxville, T en n essee ,

Defendant-Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOB THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE, NORTHERN DIVISION

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

M ich a el J . H enry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Carl A. C owan

2212 Vine Avenue, S.E.

Knoxville, Tennessee 37915

A von N. W illiam s , J r.

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

November 1967

1

Statement of Questions Involved

I.

Whether the Knoxville School System is completely

desegregated, in spite of the fact that the Negro schools

under dual operation remain identifiable as Negro schools

and are attended almost exclusively by Negro students?

The district court answered this question “Yes” and

plaintiffs-appellants contend the answer should have been

“No.”

II.

Whether the Knoxville School System should have been

ordered to pair identifiable Negro schools which could be

paired, locate new construction to help eliminate identifiable

Negro schools, and take other affirmative action to dis

establish segregation ?

The district court answered this question “No” and

plaintiffs-appellants contend the answer should have been

“Yes.”

TABLE OF CONTENTS OF BRIEF

PAGE

Statement of Questions Involved ............................ Preface

Statement of Facts ....................................................... 1

A. The General Effects of Segregation in Depriv

ing Minority Group Members of Equal Educa

tional Opportunity ............................................ 5

B. Policies of the Knoxville School System Per

petuating Segregation of the Negro Schools .... 7

C. The Educational Expert’s Proposals for Par

tial Remedies to Disestablish Segregation of

the Negro Schools ............................................ 12

A r g u m e n t ........................................................................................... 16

I. The Knoxville School System Is Not Fully De

segregated Because the Negro Schools Under Dual

Operation Remain Identifiable as Negro Schools

and Are Attended Almost Exclusively by Negro

Students .................................................................. 16

A. The relief in a class action suit against segre

gation must reach all members of the class.

B. Affirmative action must be undertaken by the

school board to eradicate the vestiges of the

dual school system and eliminate the effects of

segregation.

C. The policies of the Knoxville school system

have perpetuated segregation for the over

whelming majority of Negro students.

II. The District Court Should Have Ordered the

Knoxville School System to Pair Identifiable

Negro Schools Which Could Be Paired, Locate

IV

New Construction to Help Eliminate Identifiable

Negro Schools, and Take Other Affirmative Action

to Disestablish Segregation ................................... 28

A. The test of the propriety of equitable relief is

whether the required remedial action reason

ably tends to dissipate the effects of the con

demned actions and to prevent their continu

ance.

B. The courts of appeals have specifically held

that pairing of schools (the “Princeton plan”),

locating new construction to disestablish seg

regation, and the use of independent experts

in educational administration to formulate rem

edies are proper equitable relief for a previous

policy of segregation.

PAGE

R elief 37

TABLE OF CONTENTS OF APPENDIX

PAGE

Docket Entries and Clerk’s Certificate of Record on

Appeal ...................................................................... la

Knoxville Public School System’s Reply to Plaintiffs’

Interrogatory of March 1, 1967 .............................. 22a

Chart I—

Enrollment of Schools by Race, 1966-67 .......... 42a

Chart I l l -

Faculty Personnel by School and Race, 1966-67 48a

Chart IV—

Administrative Personnel, 1966-67 ..................... 56a

Chart V—

Reasons for Granting Student Transfers, 1966-

67 ..... 58a

Chart VII—

Special Transfers, Mountain View School........ 61a

Chart VIII—

Food Service Personnel by Race, 1966-67 ......... 62a

Chart IX—

Maintenance and Operations Personnel by

Race, 1966-67 ..................................................... 63a

Plaintiffs’ Motion for Further Relief (filed May 8,

1967) ......................................................................... 64a

Amendment to Plaintiffs’ Motion for Further Relief

(filed May 25, 1967) .................................................. 72a

Motion of Defendants to Strike or Otherwise Dispose

of Plaintiffs’ Motion for Further Relief (filed May

9, 1967) ..................................................................... 73a

V I

Transcript of Hearing of May 11, 15, 1967 .............. 74a

Dr. Morris Osbnrn, Plaintiffs’ Educational Ex

pert .................................................................... 75a

Dr. Fred Bedelle, Jr., Director of Research, Knox

ville Public School System ............................... 156a

Dr. Olin L. Adams, Jr., Superintendent of Schools,

Knoxville Public School System ...................... 293a

Rev. Frank R. Gordon, N.A.A.C.P. Chairman of

Education ............................................................ 345a

Reporter’s Certificate ........................................... 353a

List of Exhibits filed at Hearing of May 11,15,1967 .... 354a

Memorandum Opinion of Robert L. Taylor, D.J. (filed

June 7, 1967) ................................... 357a

Order of Robert L. Taylor, D.J. (filed June 7,1967) .... 390a

PAGE

V II

PAGE

T able oe Cases

Board of Education of Oklahoma City Public Schools

v. Dowell, 375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir. 1967), cert, den.,

387 U.S. 931 ......................................................... 24, 33, 37

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County, Fla. v.

Braxton, 326 F.2d 616 (5th Cir. 1964) ..................... 34

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, Va., 382 U.S.

103 (1965) .................................................................. 20

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....21,22,

26

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) ....31,33

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 219 F. Supp.

427 (W.D. Okla. 1963) .............................................. 24

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp.

971 (W.D. Okla. 1965) .......................................24, 33, 37

Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, Tenn., 373

U.S. 683 (1963) ......................................................... 20

Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401 (D.C. 1967) ...... 35

Kelley v. Altheimer, Ark. Public School Dist. No. 22,

378 F.2d 483 (8th Cir. 1967) ........................ 23, 24, 34, 37

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ........ 32

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) ........................ 32

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ............................ 20

Schine Chain Theatres v. United States, 334 U.S. 110

(1948) ......................................................................... 32

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education

et al., 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966); reaffirmed en

banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967) ...... 20,24, 33, 34, 36, 37

United States v. Standard Oil Co., 221 U.S. 1 (1910).... 32

YU1

PAGE

Wheeler v. Durham City (N. Car.) Board of Education,

346 F.2d 768 (4th Cir. 1965) ....................................... 34

Wright v. County School Board of Greensville County,

Va., 252 F. Supp. 378 (E.D. Va. 1966) ........... .......... 34

Other Authorities

Report of the United States Commission on Civil

Rights, “Racial Isolation in the Public Schools,”

Vol. I (1967) ............................................................. 31

United States Office of Education Survey, “Equality

of Educational Opportunity” ................................... 5, 6

In t h e

Inttpft §5>M?b (Emuri of Appeals

F oe t h e S ixth C ircuit

No. 18,165

J o seph in e Goss, et al.,

Plaintiff s-Appellants,

T h e B oard op E ducation op th e

C ity op K noxville, T en n essee ,

Defendant-Appellee.

appeal prom th e united states district court for th e

EASTERN DISTRICT OP TENNESSEE, NORTHERN DIVISION

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Statement of Facts

This class action was originally filed December 11, 1959

by Negro students against the Board of Education of the

City of Knoxville. The complaint, asserting rights secured

by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution, sought injunctive relief under 42 U.S.C. §1983

against the continued operation of a compulsory segre

gated school system, and requiring the Board to develop

and implement a plan for complete re-organization of the

dual schools into a unitary non-racial system. The case

has since had a long history involving several plans sub

mitted by the Board, district court hearings, modifications,

approvals, and appeals, all of which are detailed in the

2

district court’s memorandum opinion of June 7, 1967

(357a-390a) which is the subject of this appeal.

The current phase of the case arises out of plaintiffs’

objections to the Board’s purported plan of complete deseg

regation first filed in 1964 and subsequently amended, the

basic provisions of which provided:

“1. Effective with the beginning of the school year

in September, 1964, all racially discriminatory prac

tices in all grades, programs and facilities of the

Knoxville Public School System shall be eliminated

and abolished. Without limiting the generality and

effectiveness of the foregoing, all teachers, principals

and other school personnel shall be employed by defen

dants and assigned or re-assigned to schools on the

basis of educational need and other academic considera

tions, and without regard to race or color of the per

sons to be assigned, and without regard to the race or

color of the children attending the particular school or

class within a school to which the person is to be as

signed. . . .

“2. Each student will be assigned to the school

designated for the district in which he or she legally

resides, subject to variations due to overcrowding and

and other transfers for cause, and the Superintendent

may permit continued enrollment of students in their

present schools until completion of the grade require

ments for said school, provided this is consistent with

sound school administrative policy.

“3. A plan of school districting based upon the loca

tion and capacity (size) of school buildings and the

latest enrollment studies will be followed subject to

modifications from time to time as required.

3

“4. Upon written application, students may be per

mitted to transfer to schools outside their assigned

attendance zones only in exceptional cases for objec

tive administrative reasons and no transfers shall be

granted, denied or required because of race or

color. . . (370a-371a) [amended version as filed

August 6, 1965].

Plaintiffs had filed objections to paragraphs 2, 3, and 4

of the original version of the above amended “final” plan

of desegregation on February 23, 1965 (368a). These were

preserved during subsequent pre-trial conferences while

the parties attempted to negotiate their differences. At the

time of the final pre-trial conference on March 10, 1967,

the district court states: “Plaintiffs stated that a hearing

should be held on the question whether the plan had in its

operation been effective in eliminating discrimination in

the school system in compliance with the constitutional re

quirement” (372a).

In an order of July 30, 1965 following a pre-trial con

ference, the district court stated that the plaintiffs attacked

a Board of Education policy statement of April 19, 1965

“in which the Board of Education set out a Plan for per

missive continued enrollment of pupils in the year 1965-66

and thereafter in the schools attended in the previous year.

This remains as an unresolved issue in this case” (369a).

(emphasis supplied). The district court subsequently stated

in its memorandum opinion of June 7, 1967 dismissing the

case that “thus, as shown by the foregoing order which

was approved by the attorneys for the respective parties,

the unresolved issue in the case was the validity of the

[above “grade requirement” transfer provision]” (370a).

(emphasis supplied).

4

The district court entered a pre-trial order after the

final pre-trial conference of March 10, 1967, in which it

limited the issues to whether (1) the “grade requirement”

transfer provision and (2) the “brother-sister” transfer

provision perpetuated segregation and therefore violated

the Fourteenth Amendment (372a-373a). Plaintiffs sought

to have the pre-trial order amended to include the following

issues:

(3) Whether or not the Knoxville Public School Sys

tem is effectively desegregated in compliance with the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States in relation to 1) Pupil Assignment, 2)

Faculty, 3) Administrative Staff and Clerks, 4) Prin

cipals, 5) Maintenance and Operations Personnel, 6)

School Programming, 7) Organization and Curriculum,

8) Extra-Curricular Activities, 9) Facilities and New

Construction, and 10) School Boundaries or Zone Lines

(373a).

The district court denied plaintiffs’ proposed amendment, in

spite of their compliance with his request to furnish cita

tions of authority pointing out cases in which courts had

dealt with such matters, and plaintiffs excepted to the

denial (373a).

Plaintiffs then filed a motion for further relief (64a-72a)

in which they alleged generally that the zoning, transfer,

curriculum, building location, new construction, faculty as

signment, and other staffing policies of the school system

were perpetuating segregation, and sought to have the

board ordered to undertake an affirmative program to dis

establish segregation through the use of properly designed

student assignment, curriculum, new construction, and

faculty and other staff assignment policies. They also

sought an injunction against the planned new construction

5

of comprehensive junior and senior high schools in outlying

all-white areas of the city pending the adoption of such

an affirmative plan to disestablish segregation (72a).

A full evidentiary hearing was finally held before the

district court on May 11 and 15, 1967, in which the parties

were permitted to introduce proof relating to every phase

of the operation of the school system, as indicated by the

record and the district court’s discussion in its memoran

dum opinion (375a-389a). The district court then denied

all of plaintiffs’ objections to the present operation of the

school system and the injunction against new construction,

refused to order the adoption of any affirmative action

purposed to disestablish the remaining segregation in the

system, and dismissed the case on the basis that the system

was completely desegregated and court supervision was

therefore no longer required (388a-390a).

A. The General Effects of Segregation in Depriving M inority

Group M embers of Equal Educational O pportunity.

Plaintiffs offered the testimony of Dr. Morris Osburn,

Director of the Human Belations Center for Education at

’Western Kentucky University in Bowling Green, Kentucky,

who qualified as an expert in the field of public education

(75a-78a). Dr. Osburn had conducted a study of the Knox

ville public school system relating to the problem of de

segregation (79a-80a), based both on field investigation,

and on extensive data furnished by the Superintendent of

Schools, which was also entered in evidence in this case as

Exhibits 1-36 (see list, 354a-356a).

As a preliminary to his analysis of the Knoxville school

system in particular, Dr. Osburn referred to the report

authorized by the Congress in the Civil Eights Act of 1964

to be made by the United States Commissioner of Educa

tion entitled “Equality of Educational Opportunity” (also

6

known as the Coleman Report). He pointed out that the

fundamental finding of this comprehensive study was “that

children that are attending racially isolated schools are

attaining and achieving lower than children that are at

tending desegregated schools, and that the compensatory

program in these schools seemingly does not increase the

rate of achievement” (85a). Other studies which have come

to his attention also agree with the conclusion of the Cole

man Report (84a).

Dr. Osburn explained that the reason for this effect of

racial isolation of minority group members was that “the

social environment seems to have the greatest effect on

this individual and his rate of achievement” (86a). Thus,

the basic defect of the educational situation of racial isola

tion can be seen by comparison to the situation where there

is interaction with children of other races and social classes

rather than isolation, where “the low socio-economic child,

and particularly the Negro child, as he interacts with the

middle class child . . . becomes responsive, receptive, and

takes on the behavior patterns of these children and the

attitudes and the motivation to learn. . . . It is the inter

action of the peer group more than anything else that pro

motes learning and learning promotes achievement” (86a).

He also explained that although deprivation of equal edu

cational opportunity of children through isolation in a

homogeneous lower socio-economic group was not confined

to Negroes, it was accentuated in the case of Negroes be

cause of independent effects of racial isolation and because

such a large proportion of Negroes were in the lower socio

economic group (83a-88a).

7

B. Policies o f the K noxville School System Perpetuating Segre

gation of the Negro Schools.

Dr. Osburn stated that there is substantial evidence from

general educational administration studies that the loca

tion of schools itself influences the residential character of

surrounding neighborhoods, and that the designation of

particular schools as intended for Negroes or whites in

creases residential segregation since Negroes and whites

tend to locate their residences to be near their respective

schools (105a). Additional factors to be considered with

regard to zoning, Dr. Osburn pointed out, are that a large

proportion of Negroes are in the lower socio-economic group

and are therefore forced to cluster in areas of a city where

inespensive housing is available, and that there remain

considerable restrictions exercised by real estate brokers

against permitting even Negroes who can so afford to move

out of the particular areas of cities traditionally designated

as Negro (105a-108a). Ee-zoning the public schools to dis

establish segregation, he stated, would have to avoid rely

ing upon the patterns of residential segregation contributed

to by these factors (105a).

He concluded, however, that the Knoxville school system

had relied upon these factors in developing its purported

unitary zoning plan (105a-108a, 137a). After examination

of zoning maps for the old dual zones of the Knoxville

school system under segregated operation before 1960 (Ex

hibits 37-38) with the zoning maps adopted in 1960 and

since amended (Exhibits 39-42), he concluded that in most

specific instances involving the schools formerly desig

nated as Negro, the new zone lines under purported uni

tary operation paralleled closely the old zone lines under

segregated operation (93a, 96a, 98a, 102a-104a, 109a-112a,

137a).

Dr. Osburn also analyzed the relationship of the Knox

ville school system’s transfer policies to desegregation. He

8

pointed out that where all the schools in the system had

previously been all-Negro or all-white in enrollment, the

adoption of the “minority to majority” transfer provision

as part of the initial desegregation plan helped perpetuate

segregation, since students zoned to a school which had

previously been identified as intended for members of the

opposite race were thereby encouraged to transfer back to

a school which was previously identified as intended for

members of their own race. The effect of such transfers,

particularly when combined with the continuation of zones

drawn according to patterns of residential segregation, was

to continue and reinforce the identification of the Negro

schools as Negro schools since they continued to have all

or virtually all-Negro student bodies (80a-84a, 98a-101a,

136a-138a).

Even after the abandonment of the “minority to major

ity” transfer provision following its invalidation by the

Supreme Court in 1963, Dr. Osburn pointed out, the adop

tion of the “grade requirement” and “brother-sister” trans

fer provisions perpetuated its effects since these provisions

permitted students who had previously transferred under

the “minority to majority” transfer provision to remain in

the school to which they had transferred, and permitted

other members of the same family to transfer to that school

also (80a-84a, 98a-101a, 136a-138a). During the 1966-67

school year, approximately 3,400 out of a total enrollment

of 37,428 students were granted transfers out of their zone

of residence, 1,762 of which were “grade requirement”

transfers (58a-60a).

The general effects of the Knoxville school system’s zon

ing and transfer policies on the disestablishment of segre

gation appear in the 1966-67 student enrollment figures for

the schools which were designated as Negro under segre

gated operation (42a-47a) :

9

School and grades Negro White

Cansler (1-6) 221 0

Eastport (1-6) 437 1

Green (1-6) 421 21

Maynard (1-6) 452 2

Mountain View (1-6) 325 0

Sam Hill (1-6) 498 0

Beardsley Jr. High (7-10) 471 6

Vine Jr. High (7-9) 619 1

Austin Sr. High (9-12v.) 432 1

The combination of zoning and school curriculum pro

gramming in conjunction with patterns of residential seg

regation and homogeneous lowTer socio-economic class

concentrations particularly amounted to deprivation of

equal educational opportunity in the case of Austin Senior

High School, Dr. Osburn concluded. Austin High School

was the only Negro high school under the old dual system,

and became surrounded by the largest area of Negro resi

dential concentration in Knoxville. After the start of de

segregation, Austin was placed in a combined zone with

East High School, which was on the fringe between Negro

and white residential areas, and Austin was converted to

an all-vocational terminal education program while East

High School continued with a general and academic pro

gram for college preparation. Since Austin was and con

tinues as an all-Negro school in an all-Negro area, few or

no white students in the combined zone can be expected to

transfer to it because it will continue to be identified as a

Negro school, Dr. Osburn pointed out. Furthermore, many

Negro high school students can be expected to continue at

tending Austin simply on the basis of tradition and prox

imity. Since there is a general problem of a low average

level of aspiration among Negro students because of the

previous effects of segregation on themselves and in limit

ing their parents to lower socio-economic class positions,

Dr. Osburn concluded that the fact that this high school has

1 0

an all-vocational terminal education program will simply

re-inforce this low level of aspiration since there will be no

exposure to students or faculty members with different

levels of aspiration (llla-117a).

With regard to faculty integration, Dr. Osburn pointed

out the close relation to student desegregation, since the

teachers in a school are the primary adult models to which

children are exposed. Such models substantially influence

the development of the child’s self-concept of his relation to

members of the other race. For this reason, he concluded

that “it is desirable that every child in any school in our

present society should have some opportunity to be under

the supervision and the directorship, and so forth, of teach

ers of different races” (118a). Furthermore, he continued,

the existence of a faculty at a school composed exclusively

or predominantly of members of one race tends to identify

that school as intended for members of that race only,

particularly where that school was previously racially

designated under the dual system (122a).

The faculty assignments for 1966-67 at the schools which

were designated as Negro under segregated operation and

which remain with virtually all-Negro enrollments were

(48a-55a):

School Negro White

Austin Sr. High 22 4

Beardsley Jr. High 27 2

Cansler 10 4

Eastport 18 1

Green 23 2

Maynard 15 2

Mountain View 15 1

Sam Hill 20 1

Vine Jr. High 31 0

181 17

11

While there were 41 other Negro faculty members as

signed to formerly white schools in the system, 33 of the

56 formerly white schools continued to have no Negro

faculty members during 1966-67 (48a-55a).

Dr. Osburn emphasized that the factor of children taking

the adults with whom they come in contact in the school

system as models and basing their self-concept on them

also occurs with administrative and supervisory personnel,

clerks, and maintainance and operations personnel, and

thus the racial composition of staff other than faculty is

also important in a desegregation plan. He pointed out

that “children naturally look to models, they look to certain

types of behavior of models, and if children consistently

see people of one race in positions of leadership and in

positions of low esteem, children have the tendency, psy

chologists tell us, to accept these as normal things” (126a).

He added: “If white children over a period of years did

not see Negroes in responsible leadership positions they

have a tendency to believe that the Negro is inferior”

(126a).

The Knoxville School System’s Reply to Plaintiffs’ Inter

rogatory showed that principals and clerks were still as

signed on the basis of race in that the race of all principals

and clerks was the same as that of the predominant student

enrollment in the school in 1967 (48a-55a). All of the

regular supervisory and administrative personnel of the

Knoxville schools, without exception, were white (56a-57a).

In the maintenance and operations division, Negroes were

assigned exclusively to the unskilled positions of custodian,

maid, and laborer, while all skilled labor positions without

exception were occupied by whites (63a).

When queried about the relationship of extra-curricular

activities to a desegregation plan, Dr. Osburn stated that

12

“the term extra-curricular is an antiquated term” since

it has come to be realized that learning takes place during

these activities as well as during formal instruction, and

that the development of the social skills and self-concept

to which these activities particularly contribute is an im

portant part of the determination of what positions in,

society a child will have an opportunity to enter after

leaving school. Thus segregation of extra-curricular activi

ties by race and/or socio-economic class is an important

element of deprivation of equal educational opportunity

(127a-128a).

C. The Educational E xpert’s Proposals for Partial Rem edies

to Disestablish Segregation of the Negro Schools.

Dr. Osburn examined the zoning and grade structure of

each of the formerly Negro schools in relation to adjacent

formerly white schools, to determine if the most effective

means to disestablish segregation had been used, even

working within the confines of the existing school plant.

The standard and most easily applied method for effec

tively disestablishing segregation is consolidating the en

rollments of adjacent nearby Negro and white schools and

assigning all students in some grades to one school and

all students in the remaining grades to the other school

(known as “pairing” or the “Princeton plan”). This method

does not require the furnishing of transportation when the

paired schools are nearby, Dr. Osburn noted. He concluded

that the pairing device would naturally apply to several

of the formerly Negro and still virtually all-Negro schools,

hut nevertheless had not been used by the school system

(88a).

In particular, Dr. Osburn noted that still all-Negro Sam>

Hill School (capacity, 567; 1-6) was one and a half blocks

from still virtually all-white Lonsdale School (capacity,

13

675; 1-6), and that these two schools would logically have

been paired to disestablish segregation (89a-96a). Still

all-Negro Cansler School (capacity, 351; 1-6) was three

blocks from still all-white West View School (capacity,

378; 1-6), and these schools would also have been logically

paired to desegregate them (96a-99a). Virtually all-Negro

Maynard School (capacity, 486; 1-6) was approximately

three blocks from predominantly white Moses School

(capacity, 621; 1-6) and approximately four blocks from

virtually all-white Beaumont School (capacity, 1,134; 1-6),

and the grade structures and utilizations of all three schools

could be easily re-arranged to desegregate them, he con

cluded (99a-100a, 102a-104a).

Virtually all-Negro Beardsley Jr. High (capacity, 600;

1966-67 enrollment of 477) was rather close to Eule Junior-

Senior High (capacity 1,200; 7-12; 1966-67 enrollment of

1,216 white and 140 Negro), Dr. Osburn found, as demon

strated by the fact that the entire area of the Beardsley

Jr. High zone was contained within the zone of Buie Senior

High. For this reason he pointed out that an effective

desegregation plan would have re-arranged the grade struc

tures between Beardsley and Eule so that the whole six-

year program was desegregated for all of the students

(109a-llla).

Dr. Osburn also examined the Knoxville school system’s

proposed future building plans with regard to whether they

would contribute to the disestablishment of segregation.

The program for development of senior high schools in

cludes a long-range plan to construct three comprehensive

senior high school centers in outlying areas of the city—one

near the present Central High School (the Fountain city

area), one near the present West and Bearden High Schools,

and one near the present South and Young High Schools

(128a-132a). The 1966-67 enrollments of these present

14

high schools, which indicates the types of areas they serve

and/or how they are zoned, were (42a-47a):

School and grades White Negro

Central (9-12) 1,553 3

West (9-12) 774 40

Bearden (9-12) 1,013 31

South (9-12) 1,127 2

Young (9-12) 1,382 4

The fact that these projected centers will be comprehensive

schools and have vocational as well as academic cnrriculums

means that even those white students from these areas who

now come into the more integrated comprehensive high

schools in the center of the city (Austin-East, Fulton, and

Rule) for vocational curricula will probably no longer do

so, Dr. Osburn concluded (129a-131a).

The three outlying areas of the city in which the new

comprehensive centers are proposed—the North, West, and

South—are not adjacent to any substantial Negro residen

tial areas within the central city and therefore would not

draw any Negro students into them through the use of

standard zoning, Dr. Osburn pointed out, while the one out

lying area of the city in which no new comprehensive center

is planned—the East—is adjacent to the major Negro resi

dential area in the city and a comprehensive center there

would integrate substantial numbers of Negro students

through standard zoning (129a). Dr. Osburn stated:

“Based on my estimation from these reports and what I

have seen in other cities and some of the metropolitan city

areas, I feel like this is going to perpetuate a further segre

gation of [the traditionally all-Negro Austin High School]

under this situation, because, unless this changes in Knox

ville or any other city in this country, white children are

15

most reluctant to go into these former all-Negro schools”

(129a-130a).

Dr. Oshnrn added that the construction of these new com

prehensive centers for student bodies of 1,500 and more

which would be virtually all white, would increase the al

ready existing inequality of educational opportunity caused

by the fact that all-Negro Austin High School (enrollment

of 433) is less than half the average size of the other pres

ently existing high schools in the system. This inequality

results from the fact that particularly at the secondary level

the quality of the educational program increases with

the size of school, because of greater diversity of course

offerings and other factors (132a-134a). Because this

factor of the increasing quality of program as the size

of secondary schools increases, applies even beyond the

2,000 student level, Dr. Osburn suggested that not only

should changes in location of the proposed new compre

hensive high schools be considered in relation to the sub

stantial Negro residential concentrations in the eastern

central part of the city, but also that the schools be made

large enough to absorb the Negro secondary students from

the center of the city and thereby integrate them—rather

than further ghettoizing them as will the present plan

(131a-134a).

With regard to the remedy for the previous assignment

of faculty members to schools based on race, Dr. Osburn

stated that the common professional practice in the field of

education was that teachers were assigned to various

schools based on the needs for variously qualified faculty

members rather than accepting the arbitrary pattern which

would result from simply permitting all teachers to teach

in whatever school they chose, and that therefore faculty

integration should not be attempted by relying on volun

teers (123a).

16

ARGUMENT

I.

Whether the Knoxville School System Is Completely

Desegregated, in Spite of the Fact That the Negro

Schools Under Dual Operation Remain Identifiable as

Negro Schools and Are Attended Almost Exclusively by

Negro Students?

The District Court Answered This Question “Yes”

and PlaintifEs-Appellants Contend the Answer Should

Have Been “No.”

After plaintiffs-appellants had introduced substantial

expert testimony supporting their motion for further re

lief that the student assignment, curriculum programming,

building usage, new construction, and personnel policies

of the Knoxville School System were generally perpetuating

segregation rather than being designed to disestablish it,

the district court ruled that “the Knoxville School System

is desegregated under the plan which has been in operation

since the school year 1963-64” (388a) and since “there isi

no further need for the schools to operate under Court

supervision, it is further Ordered that the case be stricken

from the docket” (389a). Because the district court dis

missed the case after an exhaustive analysis of the entire

operation of the school system, this case clearly raises the

fundamental and ultimate issue in school desegregation

jurisprudence of the standard for what constitutes com

plete desegregation of a formerly de jure segregated

system.

It is important here to focus on the precise factual situa

tion involved. While approximately 32% of the Negro

students in the Knoxville School System attended sub

stantially integregated schools during the 1966-67 school

year, as the district court emphasized, it is equally true

17

that 68% of the Negro students in the system attended

schools virtually exclusively with other Negroes—schools

which had been designated as Negro schools under segre

gated operation, and which continued to have virtually all-

Negro enrollments (42a-47a). See chart, supra, p. 9. (The

school board’s assertion that 82.6% of the Negro children

in the system attended integrated schools indicates a mis

conception of the nature of the problem, since the figure

was determined by including the several schools with 400

or so Negro students each and one or two white students

each as “integrated” schools.)

Although there are Negro students attending formerly

white schools, this is clearly a fortuitous consequence of

the fact that the board was forced to adopt a unitary zoning

system under the compulsion of this litigation in 1960.

The policies of the school system since 1954 have rather

clearly perpetuated segregation for the overwhelming

majority of Negro students, rather than being directed

toward disestablishing the previously imposed segregation

completely. The Knoxville school system was absolutely

segregated by compulsion up until 1960, six years after

the Supreme Court’s desegregation order. Racially desig

nated school buildings were located in the centers of

homogeneous residential concentrations of Negroes and

whites, and naturally increased the homogeneous racial

character of the surrounding neighborhoods (105a). "When

a unitary zoning system was instituted in 1960, the zone

lines adopted nevertheless followed to the maximum ex

tent possible the patterns of residential segregation which

had been established (93a-98a, 102a-104a, 109a-112a). The

relation between the previous location of buildings for

the operation of a dual system and the subsequent adop

tion of unitary zone lines is especially graphic in situations

such as the Sam Hill (Negro) and Lonsdale (white) Ele

mentary Schools, where the two buildings are a block and

18

a half apart. A single school plant in the approximate

location of these schools serving their combined zones

would be completely integrated, but instead of merging

the operations of these two plants into a single school

through grade re-structuring, the school board drew two

separate zones around them in such a way as to preserve

each as a racially identifiable school (89a-96a).

Concurrently with the adoption of a unitary zoning

system in 1960, the school board also instituted the “minor

ity to majority” transfer policy by which a student who

was zoned to a school in which he would be in the racial

minority could obtain a transfer back to a school in which

he would be in the majority. Where all the schools in the

system had previously been designated as Negro or white,

and the new unitary zones tended to preserve those iden

tifications by following the patterns of racial residential

segregation to the maximum extent possible, the avail

ability of this transfer option naturally caused students

who perceived themselves as being in a school identified

as intended for members of the opposite race to transfer

out. The effects of such transfers were to increase the

racial identification of the schools since they made the

student bodies even more racially homogeneous than they

would otherwise have been. After this provision was in

validated by the Supreme Court in 1963, the school system

then adopted the “grade requirement” and “brother-sister”

transfer provisions which perpetuated and increased the

effects of the “minority to majority” transfers by allowing

those who had previously transferred, to remain in the

school to which they had transferred, and allowing other

members of the same family to also transfer to that school

(80a-84a, 98a-101a, 136a-138a).

The racial identification of schools was also continued

by the failure to re-assign faculty members who had orig

inally been assigned on the basis of race in the dual sys

19

tem, so that the Negro schools were still identifiable as

Negro schools by the fact that virtually all of the faculty

members were Negro (122a). It is the cumulative effect

of these zoning, transfer, and faculty assignment policies

which have caused all of the schools which were designated

as Negro under the dual system to remain identifiable

as Negro schools in that they have virtually all-Negro

enrollments (42a-47a). Thus, for example, the “minority

to majority” transfer provision and its successors was a

more potent creator of segregation because the segregated

faculties and racially homogeneous zoning clearly identified

schools as intended for Negroes or whites, and gave addi

tional impetus to minority students to transfer out.

Although granting the premise that visually obvious

racial gerrymandering of zone lines would be a constitu

tional violation, the district court determined that there

was none. As to the other objections raised by plaintiffs-

appellants, the court responded that it “is of the opinion

that there is no constitutional duty on the part of the

school board to bus Negro or white children out of their

neighborhoods or to transfer classes for the sole purpose

of alleviating racial imbalance which it did not cause, nor

is there a duty to select new school sites solely in fur

therance of such purpose” (385a) (emphasis supplied).

The court’s reference to causation suggests that the issue

becomes to what extent a school board which had pre

viously operated a de jure segregated system is responsible

for the continuing pattern of segregation which is based

in that past de jure operation, when no substantial at

tempt has been made to change that pattern, i.e. the rele

vant time-frame for determining causation.

As stated above, because the district court dismissed

the case the fundamental issue is posed as to whether on

these facts the Knoxville school system is completely

20

desegregated. While the Supreme Court has not yet con

sidered the general issue of when a formerly de jure

segregated system is fully desegregated,1 several of the

courts of appeals have come to grips with this question

in recent general decisions governing the desegregation

process (1967). The general concurrence of the Courts of

Appeals for the Fifth, Eighth, and Tenth Circuits is that

a previously de jure segregated system must undertake

substantial affirmative action to disestablish the still exist

ing patterns of segregation in the system if the simple

adoption of racially neutral policies does not do so, and

that this means in particular and ultimately that all of the

formerly Negro schools must cease being identifiable as

Negro schools both by their student enrollments and faculty

compositions. In other words, constitutionally sufficient

desegregation does not mean simply adopting provisions

by which some Negro students are permitted to attend

formerly all-white schools, while the general policies of

the system continue to perpetuate the Negro schools as

Negro schools, and therefore perpetuate segregation for

the overwhelming majority of Negro students.

In United States v. Jefferson County Board of Educa

tion et al., 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), reaffirmed en banc,

380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967), the Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit held:2

1 The Court has so far considered for their adequacy only various

specific elements of purported desegregation plans, such as the faculty

assignment issue in Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, Va., 382 U.S.

103 (1965) and Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965), and the “minority

to majority” transfer provision in an earlier appeal of this case, Goss

v. Board of Education of Knoxville, Tenn., 373 U.S. 683 (1963).

2 The portion of the original Jefferson County opinion dealing with the

substantive problem of the standard for what constitutes complete de

segregation of a formerly de jure segregated system is Section I I I (372

F.2d at 861-878), which is the most exhaustive analysis of this problem

so far undertaken by a court of appeals.

21

The two Brown decisions established equalization

of educational opportunities as a high priority goal

for all of the states and compelled seventeen states,

which by law had segregated public schools, to take

affirmative action to reorganize their schools into a

unitary, nonracial system. 372 F,2d at 847.

The Fifth Circuit recalled the basic constitutional defect

of segregation, and why the relief in a class action suit

against segregation must reach all members of the group:

Denial of access to the dominant culture, lack of

opportunity in any meaningful way to participate in

political and other public activities, the stigma of

apartheid condemned in the Thirteenth Amendment

are concomitants of the dual educational system. . . .

the separate school system was an integral element in

the Southern State’s general program to restrict Ne

groes as a class from participation in the life of the

community, the affairs of the State, and the main

stream of American life: Negroes must keep their

place.

Segregation is a group phenomenon. . . . As a group

wrong the mode of redress must be group-wide to be

adequate. Adequate redress therefore calls for much

more than allowing a few Negro children to attend

formerly white schools; it calls for liquidation of the

state’s system of de jure school segregation and the

organized undoing of the effects of past segregation.

372 F.2d at 866.

The Court therefore held:

The position we take in these consolidated cases is

that the only adequate redress for a previously overt

system-wide policy of segregation directed against Ne

groes as a collective entity is a system-wide policy of

integration. 372 F.2d at 869. (Emphasis in original.)

22

The Fifth Circuit pointed out why it held that affirmative

action must be taken by the school boards to disestablish

segregation in all schools of the system, notwithstanding

that segregation of some of the schools may appear to

resemble the fortuitous homogeneous racial concentrations

which sometimes occur in schools in other areas of the na

tion which did not have state enforced segregation.:

. .. the holding in Brown, unlike the holding in Bell but

like the holdings in this circuit, occurred within the

context of state-coerced segregation. The similarity of

pseudo de facto segregation in the South to actual de

facto segregation in the North is more apparent than

real. Here school boards, utilizing the dual zoning

system, assigned Negro teachers to Negro schools and

selected Negro neighborhoods as suitable areas in

which to locate Negro schools. Of course the concentra

tion of Negroes increased in the neighborhood of the

school. Cause and effect came together. In this circuit,

therefore, the location of Negro schools with Negro

faculties in Negro neighborhoods and white schools

in white neighborhoods cannot be described as an

unfortunate fortuity: It came into existence as state

action and continues to exist as racial gerrymandering,

made possible by the dual system. 372 F.2d at 876.

# # #

The central vice in a formerly de jure segregated

public school system is apartheid by dual zoning: in

the past by law, the use of one set of attendance

zones for white children and another for Negro

children, and the compulsory initial assignment of a

Negro to the Negro school in his zone. Dual zoning

persists in the continuing operation of Negro schools

identified as Negro, historically and because the faculty

and students are Negroes. Acceptance of an indi

23

vidual’s application for transfer, therefore, may satisfy

that particular individual; it will not satisfy the class.

The class is all Negro children in a school district

attending, by definition, inherently unequal schools

and wearing the badge of slavery separation displays.

Relief to the class requires school boards to desegre

gate the school from which a transferee comes as

well as the school to which he goes. 372 F.2d at 867-

868.

The Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit concurred

with the view of the Fifth Circuit on the question of the

standard for what satisfies the constitutional obligation to

desegregate in Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas Public

School District No. 22, 378 F.2d 483 (8th Cir. 1967), which

specifically rejected the interpretation of the Fourteenth

Amendment that “the Constitution, in other words, does

not require integration. It merely forbids discrimination.”

378 F.2d at 488. The Eighth Circuit held that there is an

affirmative obligation to disestablish segregation system-

wide :

We have made it clear that a Board of Education

does not satisfy its constitutional obligation to deseg

regate by simply opening the doors of a formerly

all-white school to Negroes. 378 F.2d at 488.

It added that this meant that the board of education must

take affirmative steps to change the identities of Negro

schools into integrated schools :

The appellee School District will not be fully deseg

regated nor the appellants assured of their rights

under the Constitution so long as the Martin School

clearly remains identifiable as a Negro school. The

requirements of the Fourteenth Amendment are not

24

satisfied by having one segregated and one desegre

gated school in a District. We are aware that it will

be difficult to desegregate the Martin School. How

ever, while the difficulties are perhaps largely tradi

tional in nature, the Board of Education has taken

no steps since Brown to attempt to change its identity

from a racial to a non-racial school. 378 F.2d at 490.

While the district court dismissed the Jefferson County

and Kelley v. Altheimer cases as being factually distin

guishable from the Knoxville case, it did not specify in

what way it thought this to be true. Both of these cases

did involve the transitional use of the so-called “freedom

of choice” type desegregation plan which is not utilized

per se in Knoxville—however, both cases were general

decisions purporting to govern the entire desegregation

process and therefore included holdings of the standard

for what would constitute a fully desegregated system,

and both cases specifically considered the question of

whether the continuation of identifiable Negro schools was

consistent with complete desegregation.

There can be no dispute that the Knoxville case is

factually identical to the case of Board of Education of

Oklahoma City Public Schools v. Dowell et al., 375 F.2d

158 (10th Cir., 1967), cert. den. 387 TT.S. 931, affirming

Dowell et al. v. School Board of Oklahoma City Public

Schools, 219 F. Supp. 427 (W.D. Okla. 1963) and 244

F. Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965), which was not discussed

by the district court.

The Oklahoma City school system had announced a for

mal desegregation plan by unitary zoning in 1955, whereas

the Knoxville schools did not take even this initial step

until 1960. After zoning its sehols in such a way as to pre

serve the maximum possible segregation without explicit

25

dual zones through following the patterns of racial residen

tial segregation, the Oklahoma City school system then in

stituted a “minority to majority” transfer plan by which

students who were unavoidably zoned to schools where they

would be in a racial minority were encouraged to transfer

to schools where they would be in a racial majority. Thus,

virtually all of the schools in Oklahoma City which had

been designated as “white” or “Negro” schools under segre

gation, remained identified as “white” or “Negro” schools

because the student bodies were almost or entirely all-white

or all-Negro. The Knoxville school system did likewise.

The Oklahoma City school system continued to assign all-

Negro faculties to schools which were all or predominantly

Negro in student body, and all-white faculties to schools

which were all or predominantly white in student body,

thereby reinforcing the identifications of various schools

as being intended for Negroes or whites rather than just

for students. The Knoxville school system did likewise.

The Oklahoma City school system located new schools in

the centers of homogeneous racial residential concentra

tions, so as to facilitate the perpetuation of segregation

through the use of zoning, transfer, and faculty assign

ment policies. The Knoxville school system did likewise.

Based on these facts, the Tenth Circuit in the Oklahoma

City case approved a district court finding that “the school

children and personnel have in the main from all of the

evidence been completely segregated as much as possible

under the circumstances rather than integrated as much as

possible.” 375 F.2d at 161, fn. 2. The Tenth Circuit stated

that “inherent in all of the points raised and argued here

by [the school board] is the contention that at the time of

the filing of this case there was no racial discrimination

in the operation of the school system.” 375 F.2d at 164.

It responded that this fact situation did constitute a case

of legal segregation which had not been disestablished, in

26

spite of the facts that zone lines had been redrawn to elimi

nate obvious duality in 1955, and that there were some

Negro students attending previously all-white schools:

As we have pointed out, complete and compelled

segregation and racial discrimination existed in the

Oklahoma City School system at the time the Brown

decision became the law of the land. It then became

the duty of every school board and school official “to

make a prompt and reasonable start toward full com

pliance” with the first Brown case. . . . The attendance

line boundaries [adopted as compliance with Brown],

as pointed out by the trial judge, had the effect in

some instances of locking the Negro pupils into totally

segregated schools. In other attendance districts which

were not totally segregated the operation of the trans

fer plan naturally led to a higher percentage of segre

gation in those schools. 375 F.2d at 165.

The Tenth Circuit then held in Oklahoma City that

“under the factual situation here we have no hesitancy in

sustaining the trial court’s authority to compel the board to

take specific action in compliance with the decree of the

court so long as such compelled action can be said to be

necessary for the elimination of the unconstitutional evils

pointed out in the court’s decree.” 375 F.2d at 166. In

cluded in the action required to eliminate the effects of

previous unconstitutional segregation was an order pairing

six-year secondary schools so that three grades of each

school were consolidated in one school and three grades

in the other school, thereby completely integrating each

school in the pair. This clearly required a school board

to take affirmative action to disestablish the pattern and

practice of segregation preserved through the use of a

zoning and transfer plan.

27

Judge Lewis concurring in the Oklahoma City case ex

plained the Tenth Circuit’s view that since compulsion was

used to maintain the system of segregation, the compulsion

inherent in school assignment policies may properly be used

to disestablish segregation:

I have no quarrel with the statement that forced

integration when viewed as an end in itself is not

a compulsion of the Fourteenth Amendment. But any

claimed right to disassociation in the public schools

must fail and fall. If desegregation of the races is to

be accomplished in the public schools, forced asso

ciation must result, not as the end sought but as the

path to elimination of discrimination. And, to me,

the argument that racial discrimination cannot be elim

inated through factors of judicial consideration that

are based upon race itself is completely self-denying.

The problem arose through consideration of race;

it may now be approached through similar but en

lightened consideration.

28

II.

W hether the K noxville School System Should Have

Been Ordered to Pair Identifiable Negro Schools Which

Could Be Paired, Locate New Construction to Help

Elim inate Identifiable Negro Schools, and Take Other

Affirmative Action to Disestablish Segregation?

The District Court Answered This Question “No” and

Plaintiffs-Appellants Contend the Answer Should Have

Been “Yes.”

Plaintiffs-appellants’ educational expert, Dr. Morris Os-

burn, Director of the Human Relations Center for Educa

tion at Western Kentucky University, had served as a con

sultant on the development of desegregation plans for

school districts in Louisiana, Mississippi, Kentucky, West

Virginia, and Illinois, and thus was well qualified to under

take analysis of the desegregation problems of the Knox

ville school system (77a-78a). After this analysis he con

cluded that three of the six Negro elementary schools

(grades 1-6) and one of the two Negro junior high schools

(grades 7-10) were close enough to nearby white schools

of the same grades that each could easily be paired in a

“Princeton plan” without producing a combined zone which

would be larger than the average elementary or junior

high zone (88a-104a, 109a-llla). See Statement, supra,

pp. 12-13.

By pairing or the “Princeton plan”, the capacities and

zones of the two nearby paired buildings are considered

as one, and all of the students in the combined zone in

some grades are assigned to one of the buildings and all

of the students in the remaining grades are assigned to the

other building based upon the capacities of the respective

buildings. Such a reorganization of the grade structures

of the paired schools does not involve the necessity to

29

provide transportation to any students if the schools are

close enough together. The three sets of elementary schools

which Dr. Osburn recommended to be paired were from

one to four blocks apart, so that even a student at the

most distant end of the old zone of one of the paired

schools would have to walk no more than one to four

blocks further if he were assigned to the other school in

the pair, and thus no transportation would have to be

furnished. Similarly, the zone of one of the junior high

schools recommended to be paired was completely within

the zone of the senior high school at which site the other

junior high school was located, so that no junior high

student in the combined zone would have to travel any

further than students eventually would for senior high

school. The pairing device is peculiarly suitable for for

merly dual school systems which frequently located two

buildings for the same grades very near to each other soi

that one could be used for Negroes and the other for whites

in the same general area. This is especially clear in the

case of the three sets of pairs of elementary schools which

Dr. Osburn recommended in Knoxville.

While the problem of disestablishing segregation of a

formerly dual school system is sometimes made difficult

by the fact that the building plants of the system were

designed and located for segregated operation and that

capital investments of this type must be used for a long

time, this fact is no longer true when it comes time to

renew the capital plant of the system by new construction.

For this reason, plaintiffs’ educational expert gave spe

cial attention to the Knoxville school system’s program for

building several new comprehensive secondary school cen

ters, which was just announced at the time of the May

1967 hearing. See Statement, supra, pp. 13-15. Dr. Os

burn pointed out that the facts that these new secondary

30

centers were planned to be located far out of the eastern

central section of the city (where the largest Negro resi

dential concentration is) in the centers of homogeneous

white suburban areas in the North, West, and South, and

that they were to be comprehensive schools including voca

tional as well as academic curriculums, meant that a num

ber of white students who had been attending the more

integrated comprehensive high school centers in the city

would no longer do so, and that in particular formerly

Negro and still all-Negro Austin Senior High and Vine

Junior High Schools would never be desegregated if this

plan were carried out (129a-134a).

Dr. Osburn therefore suggested that changes in location

of at least one and possibly more of these centers be made

in relation to the fact that the largest Negro residential

concentration is in the eastern central section of the city.

Thus a comprehensive center located on the fringe between

the eastern central section of the city and the eastern

suburban area could be substantially integrated through

the use of normal zoning. He also suggested that the cen

ters be made large enough to accomodate students from

the central section of the city as well as the suburban areas,

so as to avoid ghettoizing the center of the city. This

would also overcome the inequality caused by the fact that

all-Negro Austin High School is so much smaller than

the other present high schools in the system and will be

even smaller still by comparison to the new centers, and

that the quality of an educational program at the secondary

level increases with the size of a school (129a-134a). Al

though as the district court noted the general population

movement in Knoxville is away from the center of town

toward the outlying areas, and the school system therefore

might reasonably decide not to construct a large new

secondary center right in the center of town (378a), Dr.

31

Osburn’s analysis suggested that here are ways of lo

cating and constructing new comprehensive secondary

centers outside the center of town which would never

theless not have the extreme effect of perpetuating segre

gation as does the present plan of the Knoxville school

system.8

The district court held that there is no constitutional

duty on the part of a school board to transfer classes

(i.e. pair schools) or to select new school sites for the

purpose of integration (385a), and therefore refused to

order the school board even to consider such proposals

as those offered by plaintiffs’ expert or to undertake to

prove that they were not feasible. We submit that on

the facts of this case, this reveals an erroneously narrow

conception of the proper role of a federal court of equity

in supervising the desegregation process and assuring

that complete relief is forthcoming for the previous con

stitutional violation of operating a segregated school

system.

The Supreme Court held from the beginning that the

constitutional ban on segregation in public education re

quired far reaching affirmative action to completely re

organize the affected school systems to eliminate the prac

tice. In the second Brown decision, 349 U.S. 294 (1955),

it said that “to effectuate this interest may call for elim

ination of a variety of obstacles,” and directed the district

courts supervising the re-organizations to “consider prob

lems related to administration, arising from the physical

condition of the school plant, the school transportation

system, personnel, revision of school districts and at

8 On this point particularly, as well as various types of remedy for

disestablishing segregation generally, see the Report of the United States

Commission on Civil Rights, “Racial Isolation in the Public Schools,”

(1967), Yol. I, pp. 140-183.

32

tendance areas into compact units to achieve a system of

determining admission to the public schools on a non-

racial basis, and revision of local laws and regulations

which may be necessary in solving the foregoing problems.”

349 U.S. at 300-301.

The Court directed that “in fashioning and effectuating

the decrees, the courts will be guided by equitable prin

ciples.” 349 U.S. at 300. The general equity principle is

that there is no wrong without a remedy, and therefore

equity courts have broad power to provide relief and are

obligated to do so. The test of the propriety of measures

adopted by such courts is whether the req^^ired remedial

action reasonably tends to dissipate the effects of the con

demned actions and to prevent their continuance. Louisiana

v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965). An example of the

application of this equitable principle is in the antitrust

area, where it has been held to require the complete dis

solution of large national business enterprises, when there

is no other way to counteract the previous effects of illegal

monopolization. United States v. Standard Oil Co., 221

U.S. 1 (1910); Schine Chain Theatres v. United States,

334 U.S. 110 (1948). Similarly, it has been held to require

that federal courts conduct the redrawing of state legisla

tive districts when there is no other way to counteract the

effects of population disparities in existing state legisla

tive districts. Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964).

As indicated above, the Courts of Appeals for the Fifth,

Eighth, and Tenth Circuits have held that this equitable

doctrine, as applied to the problem of remedy for the un

constitutional creation and operation of a segregated pub

lic school system, requires a school board to undertake

substantial affirmative action purposed to disestablish seg

regation completely, and that this means specifically that

33

the formerly Negro schools must cease being identifiable

as Negro schools. The creation and operation of separate

schools for Negroes was the condemned action, and the

test of the propriety of remedial action to be required by

a court is thus whether it will disestablish the existence of

the Negro schools, i.e. integrate Negro students. The

courts have specifically held that both types of proposals

offered by plaintiffs’ educational expert—pairing (the

“Princeton plan”) and location of new construction to dis

establish segregation—are proper remedies and should be

required if necessary to disestablish segregation.

With regard to the “Princeton plan” or pairing, the

Fifth Circuit held in Jefferson County, supra:

If school officials in any district should find that

their district still has segregated faculties and schools

or only token integration, their affirmative duty to take

corrective action requires them to try an alternative

to a freedom of choice plan, such as a geographic

attendance plan, a combination of the two, the Prince

ton plan, or some other acceptable substitute, perhaps

aided by an educational park. 372 F.2d at 895-896.

The Oklahoma City case, supra, decided by the Tenth Cir

cuit, specifically upheld an order of the district court,

based upon the recommendation of outside educational ex

perts, requiring the pairing of six-year secondary schools

so that three grades of each school were consolidated in

one school and three grades in the other school, thereby

completely integrating all of the students in the paired

schools. Pairing in particular is not a major innovation,

since it is simply a way of redrawing the attendance areas

to disestablish dual schools, a redrawing which the Supreme

Court specifically ordered in the second Brown decision,

supra.

34

With regard to new construction, the Fifth Circuit’s de

cree in Jefferson County, supra, specifically states:

The defendants, to the extent consistent with the

proper operation of the school system as a whole, shall

locate any new school and substantially expand any

existing schools with the objective of eradicating the

vestiges of the dual school system and of eliminating

the effects of segregation. 372 F.2d at 900.

The Eighth Circuit in Kelley v. Altheimer, supra, a case

which directly involved a suit for injunction against new

school construction alleged to perpetuate segregation,

held:

It is clear that school construction is a proper matter

for judicial consideration. Wheeler v. Durham City

Board of Education, 346 F.2d 768 (4th Cir. 1965);

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County, Fla.,

et al. v. Braxton, et al. [326 F.2d 616 (5th Cir. 1964)].

It is also clear that new school construction cannot

be used to perpetuate segregation. In Wheeler v.

Durham City Board of Education, supra at 774, the

Court stated:

“From remarks of the trial judge appearing in the

record, we think he was fully aware of the pos

sibility that a school construction program might

be so directed as to perpetuate segregation. . . .”

Eelying upon Wheeler, the District Court in Wright

v. County School Board of Greensville County, Va.,

252 F. Supp. 378, 384 (E.D. Va. 1966) said:

“This court is loathe to enjoin the construction of

any schools. Virginia, in common with many other

states, needs school facilities. New construction,

35

however, cannot be used to perpetuate segrega

tion. . .

We conclude that the construction of the new class

rooms by the Board of Education had the effect of

helping to perpetuate a segregated school system and

should not have been permitted by the lower court.

378 F.2d at 496-497.

In the District of Columbia school desegregation case,

Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401 (D.C. 1967), the court

ordered:

In preparing the plan to alleviate pupil segregation

which the court is ordering the defendants to file, how

ever, the court will require that the defendants con

sider the advisability of establishing educational parks,

particularly at the junior and senior high school levels,

school pairing, Princeton and other approaches to

ward maximum effective integration. Where because

of the density of residential segregation or for other

reasons children in certain areas, particularly the

slums, are denied the benefits of an integrated educa

tion, the court will require that the plan include com

pensatory education sufficient at least to overcome the

detriment of segregation and thus provide, as nearly

as possible, equal educational opportunity to all school-

children. Since segregation resulting from pupil as

signment is so intimately related to school location,

the court will require the defendants to include in their

plan provision for the application of the principles

herein announced to their $300,000,000 building pro

gram. 269 F. Supp. at 515.

36

The district court in this case stated that “the point to

be recognized in a case where all other educational factors

are equal, is that the Board’s action is based upon expert

opinion” (387a), and therefore refused to give weight to

the analysis or proposals of plaintiffs’ educational expert.

While plaintiffs-appellants do not dispute that the admin

istrators of the Knoxville school system are educationally

qualified for their positions, we do submit that this state

ment indicates a misconception on the part of the district

court as to what is involved in a constitutional suit of this

type. The very essence of Constitutional Law is the pro

tection of minorities against the impermissible acts of ma

jorities acting through the power of government. Although

the administrators of the school system may qualify as

educational experts, they and the board of education as

elected officials are responsive to the political majority

which originally enacted the segregated system and which

may still wish to see it preserved as much as possible. It

is this fact which made necessary the intervention of fed

eral courts in the affairs of local school systems in the first

place to redress the constitutional violation. The Fifth

Circuit clearly recognized this in Jefferson County, supra,

when it said: “Local loyalties compelled school officials and

elected officials to make a public record of their unwilling

ness to act.” 372 F.2d at 854.

It is precisely for this reason that the detailed supervi

sion of desegregation by the federal courts—utilizing the

advice of outside experts in educational administration

who are free of local pressures, to make such supervision

meaningful as well as equitable—is crucial to the actual

achievement of the constitutionally required relief for the

creation of segregated educational systems. As the Fifth

Circuit said “judges and school officials can ill afford to

37

turn their backs on the proffer of advice . . . from any re