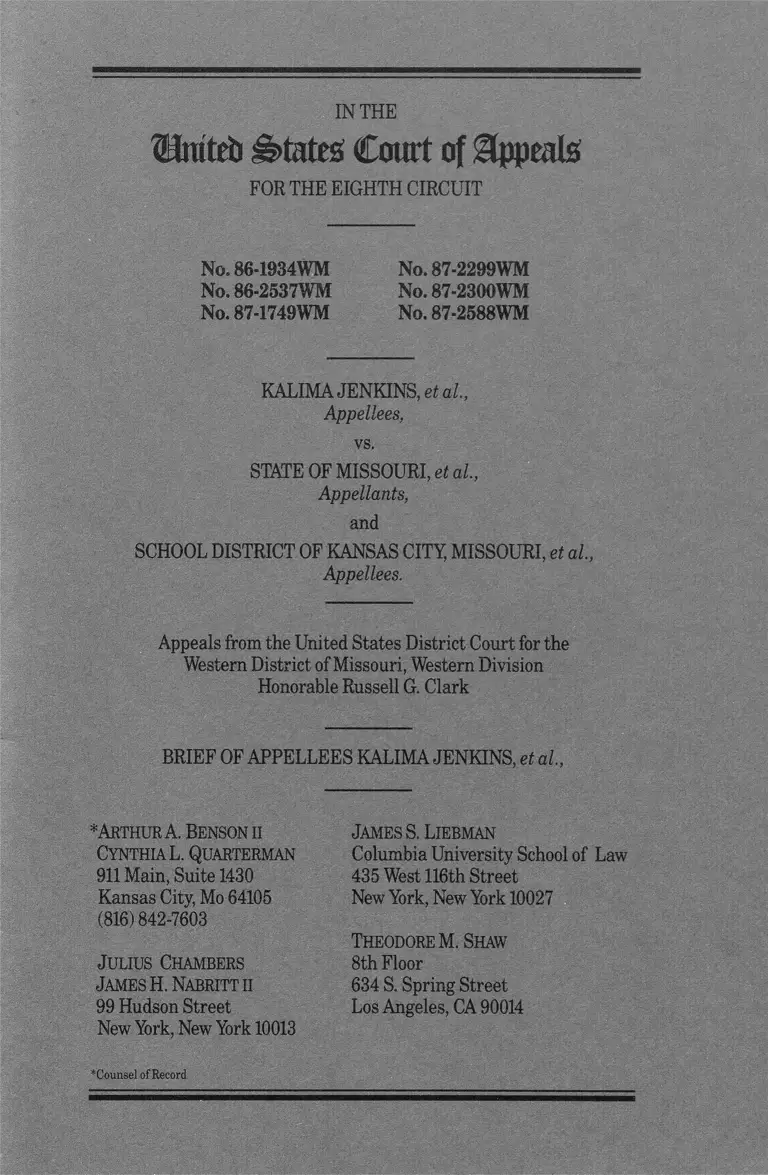

Jenkins v. Missouri Brief of Appellees Kalima Jenkins

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jenkins v. Missouri Brief of Appellees Kalima Jenkins, 1986. d4dbefe3-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3f2b6b97-f00f-427e-ad12-7dd81c27969d/jenkins-v-missouri-brief-of-appellees-kalima-jenkins. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

®rateti States Court of appeals

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

No. 86-1934WM No.87-2299WM

No. 86-2537WM No. 87-2300WM

No. 87-1749WM No. 87-2588WM

KALIMA JENKINS, et al,

Appellees,

vs.

STATE OF MISSOURI, et al.,

Appellants,

and

SCHOOL DISTRICT OF KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI, et al,

Appellees.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Missouri, Western Division

Honorable Russell G. Clark

BRIEF OF APPELLEES KALIMA JENKINS, et al,

*ArthurA.Bensonii

Cynthia L. Quarterman

911 Main, Suite 1430

Kansas City, Mo 64105

(816)842-7603

J ulius Chambers

James H .N abritt ii

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

James S .L iebman

Columbia University School of Law

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

Theodore M. Shaw

8th Floor

634 S. Spring Street

Los Angeles, CA 90014

* Counsel of Record

SUMMARY AND REQUEST FOR ORAL ARGUMENT

The United States District Court for the Western District

of Missouri (Clark, J.) has found that the School District of

Kansas City, Missouri (KCMSD) and the Missouri Appel

lants committed constitutional violations which caused

KCMSD to be racially segregated. Pre-1954 violations

caused KCMSD to operate dual schools, some for whites and

some, separate and inferior, for blacks. After 1954 KCMSD

and the State caused the conversion of KCMSD into a sys

tem of predominately black and inferior schools.

The district court found that these violations had four

primary effects in KCMSD: inferior education, segregated

schools, deteriorated buildings and an underfunded school

system.

To eliminate the vestiges of these effects the district court

ordered a remedy closely tailored to the nature and scope of

the violation. (1) To remedy inferior education, it ordered an

array of educational improvements. (2) To remedy racial iso

lation and to improve education, magnet schools were

ordered. (3) To restore the deteriorated physical plant, and

to enable the educational improvements and the desegrega-

tive magnet schools to work, the court ordered essential

capital improvements. (4) To cure the underfunding effects

and to enable the district to finance its educational

improvements, magnet schools, and capital improvements,

the court adopted a series of funding measures.

The State does not appeal the district court’s findings and

conclusions in regard to the constitutional violations and

the effects of those violations. The State here appeals the

orders providing magnet schools, capital improvements and

funding measures. Because the State has not challenged as

clearly erroneous any of the findings of the district court

and because the district court properly applied applicable

law, the orders appealed from should be affirmed. The rec

ord below is extensive and the Jenkins Class Appellees

request not less than one hour for oral argument.

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SUMMARY AND REQUEST FOR

ORAL ARGUMENT ............................................................ i

TABLE OF CONTENTS....................................................... ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................................ iv

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES .......................................x

STATEMENT OF FACTS

I. INTRODUCTION ................................................... 1

A. Violations .............................................................. 2

B. Effects .....................................................................3

C. R e m e d y ................... 3

II. NATURE AND SCOPE OF THE

VIOLATIONS.............................................................. 6

A. Introduction and Summary ............................ 6

B. Pre-1954 Requirement That Blacks Attend

Segregated and Inferior Schools in

KCMSD ...................................................................7

C. The State’s and KCMSD’s Continued

Commitment after Brown to Segregated

and Inferior Schools for Blacks ................. 11

D. The Creation and M aintenance of

an Areawide Racially Segregated

Housing M ark et............................................... 15

III. THE FOUR BASIC EFFECTS OF

THE VIOLATIONS................................................. 17

A. Relegation of an Expanding Black

Population to an Expanding Plurality

of Schools Identified by the State as

Black and In ferior ........................................... 17

B. Abandonment of KCMSD by Whites Causing

Conversion of the D istrict to a System

Identified as Black and Inferior ................. 18

C. Taxpayer Abandonment o f and Refusal

to Fund Inferior Schools ................................ 19

ii

D, D eterio ra tio n o f th e Physical P l a n t ......... 20

IV. THE REM EDIES FOUND NECESSARY

TO ELIMINATE THE FOUR EFFECTS OF

THE VIOLATIONS ............................................... 21

A. E d u ca tio n a l Im provem ents to R em edy

In fe rio r E d u ca tio n .................................... 22

B. M agnet Schools to E nd R acia l Iso la tion . . 23

C. C ap ita l Im provem ents .................................. 31

D. F u n d in g for th e R e m e d ie s .............................. 34

SUMMARY OF THE A RG U M EN T................................ 41

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT’S FINDINGS

DEMONSTRATE THAT THE REM EDIES

ORDERED FIT THE NATURE AND SCOPE

OF THE VIOLATIONS AND TH EIR EFFECTS

AND ARE NECESSARY TO DESEGREGATE

THE K C M S D ........................................ 43

A. Legal S ta n d a rd s G overning School

D esegregation R e m e d ie s ................................ 43

B. The D is tric t C ourt Followed P rec ise ly The

P ro ce d u ra l A nd S ubstan tive G uidelines For

D evising A D esegregation P l a n ................. 51

II. THE DISTRICT COURT

PROPERLY ADOPTED PLANS TO ERADICATE

THE FOUR MAJOR EFFECTS OF THE

CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLATION............. .. 55

A. To Rem edy In ferio r E d u ca tion ...................... 55

B. To R em edy S e g re g a tio n ...................................56

C. To R em edy Physical D e te r io ra t io n ...........59

D. To R em edy U n d e rfu n d in g .............................. 63

CONCLUSION....................................................................... 78

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Abelman v. Booth,

62 U.S. (21 How.) 506 (1859)............................................. 69

Action v. Gannon,

450 F.2d 1227 (8th Cir. 1971) ........................................... 75

Adams v. Rankin County Board of Education,

485 F.2d 324 (5th Cir. 1973).............................. .............. 51

Adams v. United States,

620 F.2d 1277 (8th Cir.), cert, denied,

449 U.S. 826 (1980) ...................................... 7, 8,10,11, 57

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

396 U.S. 19 (1969).............................................................. 49

Anderson v. City of Bessemer,

470 U.S. 564 (1985)..................................................... 47, 48

Arthur v. Nyquist, 712 F.2d 809 (2d Cir. 1983),

cert, denied, 466 U.S. 936 (1984).................................... 57

Banks v. Clairborne Parish School Board,

425 F.2d 1040 (5th Cir. 1970) ........................................... 51

Barrow v. Jackson,

346 U.S. 249 (1953) ......................................................... 16

Bell v. Wolfish,

441 U.S. 520 (1979)....................................................... 49,50

Berry v. School Dist. of Benton Harbor, 698 F.2d 813

(6th Cir.), cert, denied, 464 U.S. 892 (1983) ................. 57

Brewer v. Hoxie School District No. 46,

238 F.2d 91 (8th Cir. 1956)............................................... 75

Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954) (Brown I) ................................ passim

Brown v. Board of Education,

349 U.S. 753 (1955) (Brown II) .............................. passim

Carter v. West Feliciana School Board,

396 U.S. 290 (1970)..................................................... 49, 51

Cato v. Parham,

403 F.2d 12 (8th Cir. 1968)............................................... 50

iv

60

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School Dist.,

459 F.2d 13 (5th Cir. 1972).................................... ..

Clark v. Board ofEduc., 449 F.2d 493 (8th Cir. 1971),

cert, denied, 405 U.S. 936 (1972).................................... 60

Clark v. Board ofEduc. of Little Rock,

705 F.2d 265 (8th Cir. 1983)................. ............ .............. 57

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick,

443 U.S. 449 (1979).................................. 45, 48, 49, 50, 52

Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U.S. 1 (1958)...................................... ................... 69, 75

Davis v. Board of School Comm’rs,

402 U.S. 33 (1971)....................................................... 44, 49

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Bd.,

721 F.2d 1425 (5th Cir. 1983) .......................................... 56

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman,

433 U.S. 406 (1977) (.Dayton I ) ............... ...................45, 52

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman,

443 U.S. 526 (1979) (Dayton I I ) ................... 45 ,63,67,73

Edelman v. Jordan,

415 U.S. 651 (1974) ....................... ....................... 60,61,62

Evans v. Buchanan, 555 F.2d 373 (3d Cir.) cert, denied,

434 U.S. 944 (1977) (Evans V ) ................... .....................47

Evans v. Buchanan, 582 F.2d 750 (3rd Cir. 1978), cert.

denied, 446 U.S. 923 (1980) (Evans V I I I ) ............... 47, 71

Faubus v. United States, 254 F.2d 804 (8th Cir. 1958), a ff’d

sub nom. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958)........... 75, 77

Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976) ............................................................ 47

Friedman v. Fordyce Concrete, Inc.,

362 F.2d 386 (8th Cir. 1966) ............................................. 48

Gilmore v. City of Montgomery,

417 U.S. 556 (1974).............‘.......................................45,47

Green v. County School Bd.,

391 U.S. 430 (1968)..................... 44, 46, 48, 49, 51, 60, 66

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince

Edward County, 337 U.S. 218 (1964)................. 69, 70, 71

v

Gustafson v. Benda, 661 S.W.2d 11 (Mo. 1983)................. 68

Hall v. West,

335 F.2d 481 (5th Cir. 1964) ............................................. 50

Haney v. County Board of Education,

429 F.2d 364 (8th Cir. 1970)............................................. 75

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

639 F.2d 972 (3rd Cir.) cert, denied,

152 U.S. 963 (1981) (Hoots V ) .................................... 47, 50

Jenkins v. State of Missouri,

593 F.Supp. 1485 (W.D. Mo. 1984) ................... .. passim

Jenkins v. State of Missouri,

639 F.Supp. 19 (W.D. Mo. 1985) .............................. passim

Jenkins v. State of Missouri, 807 F.2d 657 (8th Cir. 1986),

cert, denied, 108 S. Ct. 70 (1987) (Jenkins I) -----passim

Jenkins v. State of Missouri,

672 F.Supp. 400 (W.D. Mo. 1987)..................... .. passim

Keyes v. School District No. 1,

413 U.S. 189 (1973).................................... .. 45, 46, 52

Lehew v. Brummell, 15 S.W. 765 (Mo. 1891)........................9

Liddell v. State of Missouri, 731 F.2d 1294 (8th Cir.),

cert, denied, 469 U.S. 816 (1984) (Liddell VII) . . . passim

Liddell v. State of Missouri,

758 F.2d 290 (8th Cir. 1985) (Liddell V I I I) ................... 73

Liddell v. Missouri,

801 F.2d 278 (8th Cir. 1986) (Liddell I X ) ................. 25, 73

Little Rock School Dist. v. Pulaski County Special

School Dist. Nos. 87-1404 et al., slip op. at 12

(8th Cir. Feb. 9 ,1988)....................................................... 70

Marhury v. Madison,

5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803)............................................. 69

Meiner v. Missouri, 673 F.2d 969 (8th Cir.), cert, denied,

459 U.S. 909, 916 (1982)............................................. 62

Milliken v. Bradley,

418 U.S. 717 (1974) (Milliken I) .............................. passim

Milliken v. Bradley,

433 U.S. 267 (1977) (Milliken I I ) ............................ passim

vi

Missouri Pacific Railroad Co. v. Whitehead & Kales Co.,

566 S.W.2d 466 (Mo. 1978)............................................... 68

Monroe v. Bd. ofComrs.,

427 F.2d 1005 (6th Cir. 1970) ........................................... 60

Morgan v. Kerrigan, 530 F.2d 401 (1st Cir.), cert, denied,

426 U.S. 935 (1976) ................................................... 45,50

Morrilton School District No. 32 v. U.S.,

606 F.2d 222 (8th Cir. 1979) cert, denied,

444 U.S. 1071 (1980).......................................................... 22

Nelson v. Grooms,

307 F.2d 76 (5th Cir. 1962) ................................................ 50

North Carolina Bd. ofEduc. v. Swann,

402 U.S. 43 (1971).............................................................. 75

Papasan v. Allain,

478 U.S. - , 106 S.Ct. 2932 (1986) ............................ 60, 63

Pitts v. Freeman,

755 F.2d 1423 (11th Cir. 1985)........................................... 60

Plaquemines Parish School Board v. United States,

415 F.2d 817 (5th Cir. 1969) ............................................. 70

Reed v. Rhodes,

500 F.Supp. 404 (N.D. Ohio 1 9 8 0 ).................................. 68

Riddick v. School Board of City of Norfolk,

784 F.2d 521 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 107 S.Ct.

420 (1986)........................................................................... 48

Shelly v. Kraemer,

334 U.S. 1 (1948)................................................................ 16

State of Missouri ex rel. Fort Osage School District

v. Conley, 485 S.W.2d 469 (Mo. App. 1972) ................... 71

Summers v. Tice,

199 P.2d 1 (Ca. 1943).......................................................... 68

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc.,

402 U.S. 1 (1979)....................................................... passim

Tasby v. Wright,

713 F.2d 90 (5th Cir. 1983)............................................... 57

Taylor v. Board ofEduc.,

294 F.2d 36 (2d Cir. 1961)................................................. 60

vii

United States v. Dist. of Cook County, 404 F.2d 1125

(7th Cir. 1968), cert, denied, 402 U.S. 943 (1971) ......... 60

United States v. Missouri, 515 F.2d 1365 (8th Cir.),

cert, denied, 423 U.S. 951 (1975)................. 70,71,72,77

United States v. Pittman,

808 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1987)...................................... .. 56

United States v. United States Gypsum Co.,

333 U.S. 364 (1948) ................................................... 47,48

West Virginia State Bd. of Education v. Barnette,

319 U.S. 624 (1943)............................................................ 70

Wheeler v. Durham City Bd. ofEduc.,

346 F.2d 768 (4th Cir. 1965)............................................. 60

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia,

407 U.S. 451 (1972)............................................................ 49

Other Authorities

Mo. Const, art. IX, § 1(a) (1945) ...........................................8

1847 Mo.Laws 103 .................................................................. 7

1865 Mo.Laws 170 .................................................................. 8

1889 Mo.Laws 226 .....................................................................8

1909 Mo.Laws 770, 790, 820 ............................. 9

Mo. Rev. Stat. § 10632 (1939) ............................................. 10

Mo. Rev. Stat. § 175.050 (1949) ........................................... 10

Mo. Rev. Stat. § 165.327 (1959)........................................... 10

Mo. Rev. Stat. § 452.1 (1959)....................................................8

Mo. Rev. Stat. § 563.240 (1959)............................... 10

Mo. Rev. Stat. § 163.087 (1986) ........................................... 64

Mo. Rev. Stat. § 164.013 (1986) ........................................... 64

Levine and Eubanks, Attracting Non-Minority Students

to Magnet Schools in Minority Neighborhoods,

19 Integrateducation 52 (1981) ...................................... 57

Restatement (Second) of Torts § 8 8 6 A .............................. 68

viii

IX

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

I. WHETHER THE DISTRICT COURT FINDINGS

DEMONSTRATE THAT THE REMEDIES ORDERED

FIT THE NATURE AND SCOPE OF THE VIOLATIONS

AND THEIR EFFECTS AND ARE NECESSARY TO

DESEGREGATE KCMSD.

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955)

(Brown II)

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) (Milliken I)

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) (.Milliken II)

II. WHETHER THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY

ADOPTED PLANS TO ERADICATE THE EFFECTS

OF THE CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLATIONS.

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 337 U.S. 218 (1964)

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) (Milliken II)

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971)

x

IN THE

Hm trb States Court of Appeals

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

No. 86-1934WM

No. 86-2537WM

No. 87-1749WM

No. 87-2299WM

No. 87-2300WM

No. 87-2588WM

KALIMA JENKINS, et al.,

Appellees,

vs.

STATE OF MISSOURI, etal.,

Appellants,

and

SCHOOL DISTRICT OF KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI, et al,

Appellees.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Missouri, Western Division

Honorable Russell G. Clark

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

I. INTRODUCTION.

The district court’s factfindings in this case1 unfolded in

three acts — violations, effects and remedies.

1 The history of this case is set out in the 1986 en banc decision of this

Court, Jenkins v. Missouri, 807 F.2d 657 (8th Cir. 1986) (en banc), cert,

denied, 108 S.Ct. 70 (1987) (Jenkins I). In summary, this Court affirmed

the dismissal of interdistrict claims, the finding of unconstitutional

segregation of the KCMSD and the initial phase of the plan to desegre

1

A. Violations.

In 1984 the district court made extensive findings of fact

establishing that the State and the KCMSD committed

three broad constitutional violations: (1) Before 1954, the

State required black children to attend racially segregated

schools. The State operated and publicly identified those

schools not simply as “for blacks only” but also as educa

tionally inferior institutions. (2) For more than two decades

after Brown v. Bd. of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (Brown I),

the State authorized and permitted local school districts to

maintain racially segregated schools, and the KCMSD did

so, adhering to a conscious policy of segregated neighbor

hood schools. With the State’s acquiesence, the KCMSD

continued to identify the schools to which blacks were

assigned as educationally inferior, and it adopted a series of

policies successfully designed to encourage white parents to

withdraw their children from those substandard schools. (3)

Simultaneously with the other two violations, the State

created and maintained a dual housing market in the Kan

sas City metropolitan area that tunneled thousands of

black families moving to the multi-district area into the

KCMSD alone.2 As a result, the district court found, the

number and percentage of black children the district was

committed to educating in separate and inferior schools

swelled — as, therefore, did the number and percentage of

the district’s schools identified as black and inferior.

gate the district. Thereafter, the district court entered orders compelling

KCMSD to implement, and the State and KCMSD to fund, plans for

magnet schools and capital improvements in the school district. Jenkins,

639 F.Supp. at 19, 46-56 (W.D. Mo. 1985), and Order, November 12,1986.

Those orders, and the orders by which they are funded, Order, July 6,

1987 and Jenkins, 672 F.Supp. 400 (W.D. Mo. 1987), are the subjects of

these appeals by the State.

2 The five-county Kansas City metropolitan area is served by thirty-

two school districts (twenty-two in Missouri, ten in Kansas), of which

thirteen lie wholly or partly within the City of Kansas City, Missouri.

2

B. Effects.

In a series of opinions in 1984-1987, the district court

identified the effects of the violations previously found. The

district court found effects falling into four major

categories.

1. Inferior education. The district court first found that

the State and the KCMSD subjected generation after gener

ation of black children to an inferior education in schools

that were publicly identified as substandard.

2. Segregation o f individual schools, then the system

as a whole. The district court next found that the State

and the KCMSD tunneled black children into and propelled

white children away from an increasing number and per

centage of KCMSD schools that were intentionally main

tained and identified as “for blacks” and inferior. As a

majority of the district’s schools fell into that category, the

district itself became identified as black and inferior, and

whites deserted the system as a whole.

3. Underfunding. Having deserted the racially iden

tified and educationally substandard school system, the dis

trict court found, the white majority of taxpayers in Kansas

City simultaneously withdrew their financial support from

the schools, refusing without exception, in 14 levy and bond

elections between 1969 and 1987, to provide needed funding

to the district.

4. Physical deterioration. As a consequence of the viola

tion’s other effects, the district court determined, the physi

cal plant of the underfunded district “literally rotted.”3

C. Remedy.

Finally, in the same series of 1984-1987 orders, the dis

trict court devised a four-part remedy that tracked the four

categories of unconstitutional effects of the violations it had

found.

3 Jenkins, 672 F.Supp. at 411.

3

1. Educational improvements. The court began by

ordering a series of educational enhancements designed to

relieve black children of a century of inferior education. The

State challenged that portion of the remedy in an earlier

appeal, and this Court en banc unanimously affirmed,

insisting that the remedy be “fully funded.” Jenkins I, 807

F.2d at 686.

2. Desegregation o f the district. Next, the district court

addressed the violations’ segregative effects, ordering a

comprehensive program of magnet schools designed volun

tarily to attract non-minority children back to the district

they previously had abandoned. Recognizing that the

State’s prior identification of the district as black and

inferior had directly led to its abandonment by whites, the

district court concluded that only by insisting upon consis

tently high quality schools could the segregative effects of

the State’s racial discrimination be reversed.

3. Capital improvements. The district court turned next

to the KCMSD’s “depressing” school facilities. Jenkins, 672

F.Supp. at 403. Finding that the educational enhancement

and desegregative components of the remedy could not suc

ceed unless the starkly visible vestiges of decades of segre

gation were eradicated from the district’s physical plant, the

district court identified and ordered a series of essential

repairs and reconstruction projects.

4. Essential funding. The district court turned finally

to the underfunding effect of the constitutional violations.

In the wake of four more unsuccessful levy and bond elec

tions, the court began by requesting the State legislature to

remove the statutory obstacles to the KCMSD’s ability to

raise the revenues needed to “fully fund”4 5 the other three

components of the remedy.6 When the State legislature

4 Jenkins I, 807 F.2d at 686.

5 The State, by its constitution and laws, prevents KCMSD from

obtaining revenue from any tax source other than the property tax and

allows revenue from the property tax to be increased only by a two-

4

refused, the district court concluded that the en banc man

date of this Court left it with “no choice”* 6 but to order what

the State could — but had refused to —■ accomplish volun

tarily. The district court accordingly ordered an increase of

the property tax levy for the KCMSD and the collection of

additional funds through a tax on income in the community

served by the district’s schools.

In its brief, the State ignores the first two acts in which

this case has unfolded — the acts revealing the State’s will

ful role in fostering racial discrimination, racial hostility,

and stubborn racial separation. Instead the State focuses in

isolation on the final, remedial, act.7

As this Court is well aware, however, school desegrega

tion remedies may neither be drawn nor reviewed in isola

tion from the violations and consequences that compel the

remedy. Rather, the nature and scope of the violation and

its effects determine the nature and scope of the remedy.

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1,

16 (1971). Because appellants’ brief leaves out the critical

first two-thirds of the story, the appellee class of KCMSD

school children has no choice but to begin at the beginning

thirds vote of its electorate, both to issue bonds and, absent

reassessment measures, to raise its levy.

6 Jenkins, 672 F.Supp. at 411.

7 One result of the State’s excision of two-thirds of the history of the

case is an attempt to make the District Judge, not itself, the villain of

the story. As evidenced by the prior en banc appeal, the district court

has by no means afforded plaintiffs the full measure of relief they have

sought. Nonetheless, the plaintiffs consistently have recognized the

extensive, careful and conscientious efforts the District Judge has

devoted to a difficult case for so long and register a protest at the outset

about the State’s caustic remarks about Judge Clark. See, e.g., State’s

Brief at 47 (lacking expertise the district court “seeks to remake the

KCMSD according to a dubious and untried theory”), at 19 (“the district

court has simply lost sight of the proper role of a federal judge”), or at 45

(alleging the district court failed “to distinguish between a judicial pref

erence and a constitutional necessity”).

5

and to lay out carefully the facts and consequences of the

State’s intentional racial discrimination tha t the district

court found and that the Constitution says must be

remedied.8

Notwithstanding the State’s assertions, the district court

no more constructed its remedy determinations out of whole

cloth than it did its detailed violation and effect findings.

Rather, the district court heard evidence during 93 days of

trial on the constitutional violation and its effects and 29

days of hearings on the remedy, supported by tens of thou

sands of pages of documents on remedies alone. What fol

lows, then, is a summary of the district court’s violation,

effects and remedy findings and the extensive evidence on

which those findings are based.

II. NATURE AND SCOPE OF THE VIOLATIONS.

A. Introduction and Summary.

In its opinion detailing the constitutional violations, Jen

kins, 593 F.Supp. 1485 (W.D. Mo. 1984), and in its sub

sequent orders, the district court found pre- and post-1954

violations by KCMSD and the State. The pre-1954 violations

consisted of the concentration of blacks in KCMSD and

establishment and operation of a dual system of schools

within KCMSD.9 Some schools were reserved exclusively for

whites, others for blacks.10 Those schools reserved for blacks

were inferior and as a result, the district court found, the

State induced, and placed its “imprimatur” on, the assump

tion that black schools are by nature inferior.11 The post-

1954 violations by KCMSD and the State were the conver

8 Because in neither this appeal nor the last has the State challenged

either the district court’s violation or effects findings, those findings,

summarized below, are law of the case.

9 Jenkins, 593 F.Supp. at 1490-91 (all school districts in Missouri par

ticipated in a system of segregated schools).

10 Id. at 1492.

11 Id. at 1492,1503.

6

sion of the school district from a system of dual schools, a

minority of which were operated for blacks and were

inferior, into an entire system of predominantly black and

inferior schools. This transformation was caused by inten

tionally segregative school and housing actions that tun

neled black families into the district and propelled white

families out of the district12 and by acts and failures to act

of the State and KCMSD in violation of their affirmative

duties to dismantle the effects of their pre-1954 discrimina

tion.13

The following discussion delineates the district court’s

violations findings and identifies the portions of the record

that support the findings.

B. Pre-1954 Requirem ent That Blacks Attend

Segregated and Inferior Schools in KCMSD.

In its violation decision, Jenkins, 593 F.Supp. 1485, the

district court made the following findings:

The State admitted, and the Court judicially

noticed tha t Missouri mandated segregated

schools for black and white children before 1954 ..

. . This historical background is recounted in more

detail by the court in Adams v. United States, 620

F.2d 1277,1280-81 (8th Cir.), cert, denied, 449 U.S.

826,101 S.Ct. 88, 66 L.Ed.2d 29 (1 9 8 0 ) .. . .14

Each school district in Missouri participated in

this dual school system before it was declared

12 Id. at 1494.

13 Id. at 1504-05.

14 In the referenced passage from Adams, this Court found that:

[plrior to the Civil War, a Missouri statute provided: No per

son shall keep or teach any school for the instruction of

negroes or mulattoes, in reading or writing, in this State. Act

of February 16, 1847, § 1, 1847 Mo.Laws 103. Beginning in

1865, the Missouri General Assembly enacted a series of

statutes requiring separate public schools for blacks. See,

7

unconstitutional in Brown I. Districts with an

insufficient number of blacks to maintain the

state-required separate school made interdistrict

arrangements to educate those children. Undeni

ably, some blacks moved to districts, including the

KCMSD, that provided black schools.

Jenkins, 593 F.Supp. at 1490.

The KCMSD did not mandate separate schools for

blacks and whites. The people of the State of Mis

souri through constitutional provision and the

General Assembly through legislative enactment

mandated that all schools for blacks and whites in

the State were to be separate. There is no room for

doubt but that the State of Missouri intentionally

created the dual school system.

Id. at 1503-04.

The record below includes extensive evidence supporting

these findings. As the evidence reveals, Missouri’s history of

segregating blacks into separate schools by law began as

the Civil War ended. Id. Missouri’s 1865 constitution per

mitted separate schools based on race, and its 1875 constitu

tion required racial separation in provisions tha t remained

e.g., Act of February 17,1865, § 13,1865 Mo.Laws 170; Act of

June 11, 1889, § 7051a, 1889 Mo.Laws 226. This segregated

system was incorporated into the Missouri Constitution of

1945, which specifically provided that separate schools were

to be maintained for “white and colored children.” See

Mo.Const, art. IX, § 1(a) (1945). Although a 1954 Attorney

General opinion declared this provision unenforceable fol

lowing Brown I, it remained a part of the state constitution

until repealed in 1976. Statutes implementing the constitu

tionally mandated segregation provided for separate fund

ing, separate enumerations, separate consolidated “colored”

school districts, and the interdistrict transfer of black stu

dents. Most of these statutes were not repealed until 1957.

See Act of July 6,1957, § 1,1957 Mo.Laws 452.

Adams v. United States, 620 F.2d 1277,1280 (8th Cir. 1980).

8

in the document until their repeal in 1976. In 1889, the

State legislature made it a criminal offense for “any colored

child to attend a white [public] school,” 1889 Mo. Laws 226,

and in 1909 broadened the offense to include private

schools. 1909 Mo. Laws 770, 790, 820. Before 1954, Missouri

strictly enforced its laws mandating school segregation. See

Lehew v. Brummell, 103 Mo. 546,15 S.W. 765 (1891). In 1910,

the Attorney General threatened to prosecute school offi

cials operating integrated schools. P.Ex. 178; Tr. 4,225,

14,813. In 1948 the State Board of Education invoked its “in

herent authority” to withdraw funding from a school dis

trict violating Missouri’s segregation provisions. P.Exs.

2222-25.15

Local officials followed the lead of the State. In 1914, the

Kansas City Council made it illegal to establish any “school

. . . for . . . persons of African descent” within one-half mile

of a school for “persons not of African descent” in order to

avoid attracting black residents to white neighborhoods.

P.Ex. 124-A. The Kansas City planning department for 35

years before 1955 divided the city into “white” and “colored

districts” defined by their proximity to racially identified

schools. P.Exs. 282-B, 288-89, 306-07.

Whereas the Kansas City School District maintained a

comprehensive system of white schools (70 in 1954) and

black schools (16 in 1954),16 the districts surrounding the

KCMSD operated a haphazard system for blacks of “no

schools, poor schools, a system where [tuition and] trans

portation was not provided quite often.” Tr. 4,328. The

uneven availability of segregated schools in the area before

1954, the district court explicitly found, was among the rea

15 Undated transcript and exhibit citations are to the record of the vio

lation trial and were before this Court in the 1985 appeals, Nos. 85-

1765WM, 1949WM and 1974WM. Citations to the record of the remedy

proceedings include the date of the hearing to distinguish overlapping

page and exhibit numbers.

16 KCMSD Ex. K-2.

9

sons “some blacks chose to move into the KCMSD.” Jenkins,

593 F.Supp. at 1490. In particular, the district court found

that, as tens of thousands of blacks migrated to the Greater

Kansas City area from the Deep South in the decades

before Brown I, the “availability of schools would influence,

more specifically, what housing choice would be made

within the city.” Id.

The district court noted, as has this Court on previous

occasions,17 that the State combined school segregation with

numerous other discriminatory actions against blacks.18

The district court explicitly found that such actions by the

State not only separated the races, but in addition iden

tified the institutions and neighborhoods to which blacks

were relegated — indeed, they identified blacks themselves

— as “inferior.” The district court specifically found that the

“inferior education indigenous of the state-compelled dual

system has lingering effects in the Kansas City, Missouri

School District,” including a “general attitude of inferiority

among blacks [which] produces low achievement [and]

which ultimately limits employment opportunities and

causes poverty.” Id. at 1492.

Not only blacks were affected by their enforced separation

from the rest of society and by the substandard nature of

the schools and neighborhoods to which they were confined.

In addition, the court found, the State’s segregative actions

“had the effect of placing the State’s imprimatur on racial

17 See Adams v. United States, 620 F.2d 1277,1280 (8th Cir. 1980).

18 The State “mandated separate schools for blacks and whites; it

established separate institutions for teaching black school teachers,

§ 10632 R.S.Mo. (1939); it established and maintained a separate institu

tion for higher education for blacks at Lincoln University, § 175.050

R.S.Mo. (1949); it provided that school boards in any town, city or con

solidated school district could establish separate libraries, public parks

and playgrounds for blacks and whites, § 165.327, R.S.Mo. (1959); it

made it a crime for a person of Vs Negro blood to marry a white person,

§ 563.240 R.S.Mo. (1959); and its courts enforced racially restrictive

covenants.” Jenkins, 593 F.Supp. at 1503.

10

discrimination,” and “created an atmosphere in which the

private white individuals could justify their bias and

prejudice against blacks” and their institutions. Id. at 1503.

As a result, “[a] large percentage of whites do not want

blacks to reside in their neighborhood” or to attend their

schools, and “a large percentage of blacks do not want to

reside . . . [where] they are not wanted.” Id.

C. The State’s and KCMSD’s Continued Commitment

after Brown to Segregated and Inferior

Schools for Blacks.

In its various decisions, the district court found, inter

alia, that:

[Missouri’s segregation] provisions were not

immediately and formally abrogated after the

Brown decision was announced . . . . This histori

cal background is recounted in more detail by the

courts in Adams v. United States, 620 F.2d 1277,

1280-81 (8th Cir.), cert denied, 449 U.S. 826, 101

S.Ct. 88, 66 L.Ed.2d 29 (1 9 8 0 ) .. . .19

Jenkins, 593 F.Supp. at 1490.

[After Brown], the District [KCMSD] chose to

operate some completely segregated schools . . . .

The Court finds the District did not and has not

entirely dismantled the dual school system. Ves

tiges of that dual system still remain.

Id. at 1492-93.

19 In the referenced passage from Adams, this Court found that prac

tices in St. Louis almost identical to those adopted by KCMSD, and obvi

ously without objection from the State, caused “pre-Brown white schools

located in the black neighborhoods [to] turn[] virtually all black

immediately after the [neighborhood school] plan was implemented.”

Adams v. United States, 620 F.2d 1277, 1281 (8th Cir. 1980). See also id.

at 1288 (“The Board’s steadfast adherence to a student assignment pol

icy which did not desegregate the schools and its use of intact busing,

school site selection, block busing, permissive transfers, and faculty

assignments have preserved segregation in the school system.”)

11

[T]he Court finds the use of [KCMSD’s post-

Brown policies] did not aid to integrate the Dis

trict; to the contrary [they] allowed attendance

patterns to continue on a segregated basis . ..

The Court finds the District’s [post-1954] use of

intact busing had a segregative intent and effect.

Id. at 1494.

[T]he State as a collective entity cannot defend its

failure to affirmatively act to eliminate the struc

ture and effects of its past dual system on the

basis of restrictive state law. The State executive

and its agencies as well as the State’s General

Assembly had and continue to have the constitu

tional obligation to affirmatively dismantle any

system of de jure segregation, root and branch.

This obligation is parallel with the obligation of

the KCMSD. This case is before this Court simply

because the KCMSD and the State have defaulted

in their obligation . ..

Id. at 1505.

These parallel findings are supported by extensive sub

sidiary findings and record evidence. At the time of Brown

I, KCMSD operated a fully segregated system of schools

with a small minority of substandard schools reserved for

blacks and the rest reserved for whites. Notwithstanding

the mandate of Brown I and Brown II, the district court

found, the State did not set about eliminating segregation

and its effects. Instead the State invited local school dis

tricts to maintain racial segregation, and the KCMSD did

just that, committing itself until the mid-1970’s to a policy

under which some schools were predominantly black, the

rest were nearly all white, and white students in predomi

nantly black zones were invited to transfer out to white

schools.

Until 1954, Missouri had assiduously enforced segrega

12

tion through its civil, criminal and administrative laws,

even invoking its “inherent authority” to cut off state funds

for education to assure continued segregation. P.Exs. 2222-

25. Immediately after Brown I, however, Missouri washed

its hands of the entire m atter of segregation and its effects.

On June 30, 1954 the Attorney General of Missouri issued

an opinion stating that local school districts “may . . . per

mit ‘white and colored’ children to attend the same schools,”

but leaving districts free to decide “whether [they] must

integrate.” P.Ex. 2322 (emphasis added). Thereafter, Mis

souri consistently has insisted tha t school desegregation is

a m atter exclusively for local control. P.Ex. 465.20 As the dis

trict court stated, it has “not been informed of one affirma

tive act voluntarily taken by the Executive Department of

the State of Missouri or the Missouri General Assembly to

aid a school district tha t is involved in a desegregation pro

gram.” Order, November 12, 1986 at 7. Missouri left to

KCMSD the entire responsibility for eliminating the effects

of segregation Missouri had compelled KCMSD to imple

ment.21

After Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 753 (1955)

(Brown II), KCMSD intentionally operated its schools on a

neighborhood school basis with attendance boundaries

drawn to conform to racially segregated neighborhoods.

Jenkins, 593 F.Supp. at 1493.22 The district court found that

20 Compare P.Ex. 2463 (December 12,1973 letter from State Education

Commissioner Mallory to State Board of Education contrasting public

position that the State “really cannot do anything about” segregation in

the Kinloch case with his “true” opinion that “the General Assembly

could do something about this entire matter of having segregated

schools in Missouri. . . ”).

21 “The KCMSD did not mandate separate schools for blacks and

whites . . . . [T]he State of Missouri intentionally created the dual school

system.” Jenkins, 593 F.Supp. at 1503-04.

22 In 1956, after fully implementing its neighborhood plan, the

KCMSD enumerated 9,193 black and only 150 white students in schools

more than 90% black and only 343 black and 40,779 white students in

schools less than 10% black. KCMSD Ex. 2.

13

“adoption of the neighborhood school concept did not sub

stantially change the segregated school system.” Id. at 1493.

Rather, the effect of the district’s attendance zone policies

was to maintain two separate school systems within

KCMSD, segregated by race. Most particularly, until 1976,

school attendance boundaries in KCMSD did not cross

Troost Street for its entire 80 block pathway through the

district. Tr. 3,311-12, 9,362-66, 10,385-86. Two sets of high

schools were located on either side of Troost, each segre

gated by race — blacks to the east, whites to the west —

and each with its own feeder junior high and elementary

schools. KCMSD Ex. 1.

Likewise, for nearly 15 years after Brown I, KCMSD

adopted hundreds of small attendance boundary changes

which, in almost all cases, kept whites and blacks separate

as the black population grew. Stipulation of Fact, February

21, 1984. The district court found that these “attendance

zone changes did not achieve system-wide integration.” Jen

kins, 593 F.Supp. at 1494.

Segregation and the identification of blacks and the

schools they attended as inferior were explicitly continued

until 1965 through the district policy of intact busing —

busing “entire classrooms of black students to predomi

nantly white schools but” keeping “them as an insular

group, not allowing them to be mixed with the receiving

population.” Id. The district court found that this intact

busing had “segregative intent and effect.” Id.

The district court found that “inferior education” lingered

in the predominantly black schools in KCMSD after 1954.

Id. at 1492. See also Tr. 3,013-16. The record demonstrates

precisely how the district’s educational policies fostered the

continuing reality and perception of black schools as

inferior. For example, when HEW forced KCMSD to inte

grate its teaching staff, the district transferred its best and

most experienced black teachers to white schools, leaving

less capable teachers in black and racially changing

14

schools. Tr. 3,298-99, 3,304-06. Likewise, as schools became

identified as black, college preparatory classes, especially

in the sciences, were discontinued and replaced by voca

tional courses such as “janitorial services.” Tr. 7,018-21,

7,306-20, 7,344, 7,338-41, 8,624-25, 8,969-70, 9,419-20,15,147,

15,149-50; Stipulation, February 21, 1984 at 75. Once again,

governmental actions “had the effect of placing the State’s

imprimatur on racial discrimination” against blacks and

the schools in which they predominated and “created an

atmosphere in which private white individuals could justify

their bias and prejudice against blacks” and their institu

tions. Jenkins, 593 F.Supp. at 1503.

As the black population within previously white atten

dance zones grew,23 and as the education provided by the

schools there deteriorated, KCMSD adopted the use of

optional attendance zones which permitted white students

and their parents to choose between two schools — invari

ably the one in their neighborhood which was predomin

antly black and another somewhere else that was predo

minantly white. Stipulation, February 21, 1984; KCMSD

Ex. 2. Together with a liberal transfer policy, used most fre

quently by whites, the district’s assignment policies invited

and encouraged white children living in racially transi

tional neighborhoods to “transfer within the district to whi

ter schools.” Jenkins, 593 F.Supp. at 1493. The district court

found that “the use of these optional zones, coupled with the

liberal transfer policy, did not aid to integrate the district;

to the contrary, it allowed attendance patterns to continue

on a segregated basis.” Id. at 1494.

D. The Creation and M aintenance of an Areawide

Racially Segregated H ousing Market.

The State’s and KCMSD’s pre- and post-1954 school

segregation violations coincided with a third, housing, vio

23 The State’s school and housing violations, as detailed in the follow

ing section, caused the black population to expand in this segregated

manner.

15

lation which “caused the [KCMSD’s] public schools to swell

in black enrollment,” at the same time as it made “whites

move[] out” of the increasingly minority district to the sub

urbs. Id. at 1491,1494.

The district court found and the record demonstrates that

the State’s segregated dual housing market and its

statewide system of segregated schools, id. at 1491, meant

that blacks would “move into the KCMSD,” id. at 1490,

choose housing based on the “then availability of schools,”

id., and reside in neighborhoods characterized by an “inten

sity of segregation,” id. at 1491, which had long-lasting and

virulent demographic effects. Among the “positive actions”

of the State “which were discriminatory against blacks,” the

state enforced racially restrictive covenants and “created an

atmosphere in which . . . private white individuals could

justify their bias and prejudice against blacks

. . . . [with a continuing] significant effect. . . in the Kansas

City area.” Id. at 1503.

“Racially restrictive covenants were intended to cause

housing segregation” and “were enforced by the courts of

Missouri until after the case of Shelly v. Kraemer, 334 U.S.

1, 68 S.Ct. 836, 92 L.Ed. 1161 (1948),” i.e., until the Missouri

case of Barrow v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953). Jenkins, 593

F.Supp. at 1497. Recorded on “a large proportion of the resi

dential land uses in 1947,” Tr. 13,024, these covenants, like

segregated schools, tunneled in-migrating blacks into the

black-concentrated areas near KCMSD’s segregated

schools. Tr. 14,878-79. Their widespread adoption of racially

restrictive covenants “limited black housing supply, . . . con

fined [blacks] to older areas .. . [and] resulted in overcrowd

ing, high density, [and] deteriorated conditions” in the area

around KCMSD’s all-black schools, contributing to white

flight from and avoidance of those areas, and, ultimately,

out of the KCMSD itself. Tr. 13,033-35, cited in Jenkins, 593

F.Supp. at 1491.

The district court found that the State “encouraged racial

16

discrimination by private individuals in the real estate,

banking and insurance industries.” Id. at 1503. This dis

crimination consisted in large part of blockbusting, steering

and red-lining, by which blacks “were steered or channeled”

into areas surrounding or immediately to the south and

east of KCMSD’s all-black schools. Tr. 12,339, cited in Jen

kins, 593 F.Supp. at 1491. Together with the liberal transfer

and optional school zone policies, the attendance boundary

and curriculum changes and the teacher assignment prac

tices, supra at Section II.C., these state housing violations

caused a “large number” of whites to flee changing neigh

borhoods in the KCMSD for the surrounding school dis

tricts and private schools. Order, August 25,1986 at 1.

III. THE FOUR BASIC EFFECTS OF THE

VIOLATIONS.

The district court found tha t the State’s and KCMSD’s

violations had four systemwide effects, discussed below.

A. Relegation of an Expanding Black Population to

an Expanding Plurality of Schools Identified by

the State as Black and Inferior.

The district court found that “the state-compelled dual

school system” in KCMSD caused “inferior education” with

“lingering effects.” Jenkins, 593 F.Supp. at 1492. Prior to

1954, the State’s provision of inferior schools for blacks in

the Kansas City area consisted of denying blacks outside

KCMSD a high school education and providing, intermit

tently, only a few elementary schools, all of which were

inadequate. P.Exs. 114, 210. While the schools KCMSD pro

vided for its black students were better than those in sur

rounding areas, e.g., Tr. 1,792-93, 1,905-06, 3,534-38, they

nonetheless were generally “quite inferior” to white schools.

Tr. 16,835, 818-24,1,743-46.

KCMSD’s identification of black schools as inferior con

tinued after 1954. Downgraded curriculum, assignment of

inexperienced teachers, the district’s failure to take positive

17

steps to desegregate previously black schools, and stig

matizing attendance policies that designated increasing

numbers of schools with blacks as places from which white

children should escape, denigrated the quality of the

schools to which blacks were assigned and perpetuated

their labeling as inferior. See supra at Section II.C. As the

district court found, education in KCMSD was “bogged

down” by segregation. Jenkins, 639 F.Supp. at 28 (quoting

the State’s publication, Reaching for Excellence, KCMSD

Ex. K-75.

Simultaneously, the court found, the State’s enforcement

of restrictive covenants before 1954 and its encouragement

of redlining, blockbusting and steering after 1954 caused

KCMSD’s schools to swell in black population. As the black

“community expanded in a southeast direction so did the

black schools.” Jenkins, 593 F.Supp. at 1492. For example,

Central High School, all-white in 1954, became 97% black in

1961; Southeast, all-white in 1954 and 92% white in 1963,

became 98% black in 1973. KCMSD Ex. 2. During the same

period, KCMSD schools not designated for blacks remained

all-white. As late as 1974, 80% of all blacks in the districts

attended schools that were 90% or more black. Id. at 1493.

As a result, the number and percentage of KCMSD schools

identified as black and inferior burgeoned in the decades

after Brown. Thus, while in 1956, only 16 (18%) of KCMSD’s

schools were majority black, by trial that number had risen

to 45, and the proportion of such schools was 63%. KCMSD

Ex. K-2.

B. Abandonment of KCMSD by Whites Causing

Conversion of the District to a System Identified

as Black and Inferior.

The district court found that “inferior education” was a

direct result of segregating students in KCMSD, Jenkins,

593 F.Supp. at 1492, quoting Brown I, and affected the

“hearts and minds [of school children] in a way unlikely

ever to be undone.” Brown /, 347 U.S. at 494. The district

18

court found segregated schools to cause an “attitude of

inferiority among blacks [which] produced low achievement

[and] which ultimately limits employment opportunities

and causes poverty.” Jenkins, 593 F.Supp. at 1492.

The district court also found tha t the combined effects of

operating KCMSD’s black schools for a century as educa

tionally inferior and of causing the number and percentage

of such schools to expand after 1954 were demographically

devastating to the district. In the first place, the State’s and

KCMSD’s violations “created an atmosphere in which the

private white individuals could justify their bias and

prejudice against blacks” and inferior black schools. Id. at

1503. “A large percentage of whites do not want blacks to

reside in their neighborhood” or to attend their schools. Id.

As a direct result, the district court repeatedly found, the

invidiously motivated operation of an increasingly large

number and percentage of KCMSD’s schools as black and

inferior “led to white flight from the KCMSD to suburban

districts, a large number of students leaving the schools of

Kansas City and attending private schools.”24

C. Taxpayer Abandonment o f and Refusal to Fund

Inferior Schools.

The district court next pointed to “the detrimental effects

that segregation has had on this school district’s ability to

24 Order, August 25, 1986 at 1. See also Jenkins, 672 F.Supp. at 412

(“abundance of evidence” of white flight to the suburbs); 593 F.Supp. at

1494 (as schools in an area became black “whites moved out” to the sub

urbs). The extent to which the KCMSD had become a system of schools

for blacks is indicated by comparing the district to those surrounding it.

At the time of trial, 87% of the black students in the Kansas City met

ropolitan area attended KCMSD schools, while 89% of the white stu

dents were in the SSDs. KCMSD was 68% black and the SSDs were

about 5% black at the time of trial. P.Ex. 53-G. The racial concentration

within KCMSD is further exemplified by teacher data. At the time of

trial, 96% of the area’s minority teachers worked in KCMSD as did 100%

of the minority counselors and 99.5% of the minority school adminis

trators. See also P.Ex. 721-G.

19

raise adequate resources.” Jenkins, 639 F.Supp. at 41.

Uncontroverted evidence before the district court estab

lished that, as a result of the constitutional violations,

KCMSD since 1970 has been a majority white school district

measured by its resident or voting population, but a two-

thirds to three-fourths black school district measured by its

student body. White parents with children (in most areas, a

mainstay of tax support for the public schools) were driven

from the district to the suburbs and to private schools to

avoid what the State and KCMSD had transformed into

segregated schools publicly identified as inferior. The result

was a systematic refusal by taxpayers — dating from pre

cisely the moment when the school district became majority

black — to give their approval, as required by state law, to

any levy increases or bond issues.25 This and other evidence

convinced the district court that the constitutional viola

tions “contributed to an atmosphere which prevented the

KCMSD from raising the necessary funds to maintain its

schools.” Jenkins, 672 F.Supp. at 403.26

D. D e terio ra tio n of th e Physical P lan t.

Chief among the “detrimental effects tha t segregation

has had on this school district’s ability to raise adequate

resources,” the district court determined, was the deteriora

tion on a massive scale of KCMSD’s physical plant. Jenkins,

25 See, e.g., Tr. 22,983 (black wards tended to give highest voter per

centages in favor of revenue measures); Tr. August 6,1987 at 567-91, 599

(segregation polarized voting on racial lines; school board unable to pass

revenue measures because of segregation and its aftermath; district in

desperate financial condition, furloughed 450 teachers, stopped repair

ing buildings; quality of education declined; white enrollment declined);

Hamann Affidavit, Exhibits B and C of Attachment 2, KCMSD Motion

for Court Order Enjoining Proposition C Levy Rollback (ten of twenty-

four wards in KCMSD are predominantly black and in February, 1986

levy election accounted for 23% of the votes cast, predominantly white

wards accounted for 62% and four wards with substantial populations of

both blacks and whites accounted for 15%).

26 See also Order, November 12,1986 at 4.

20

639 F.Supp. at 39-41. Those deteriorated conditions, the

court found, consist of safety and health hazards, impair

ments of the educational environment and functional

impairments which cause problems including “extremes of

heat and cold due to faulty heating systems, peeling paint,

broken windows, odors resulting from inadequate and

deteriorating ventilation systems, improper lighting,” as

well as inadequate space for classrooms, libraries, resource

rooms, and storage rooms. Id. at 39-40.

As the district court also found, the four effects of the vio

lations replicate themselves: the physical deterioration of

the schools further diminishes educational quality, which,

in turn, causes additional white flight, additional erosion in

taxpayer support, and additional deterioration of the

schools.27

IV. THE REMEDIES FOUND NECESSARY TO

ELIMINATE THE EFFECTS OF THE VIOLATIONS.

As it began the process of issuing orders to remedy the

violations it had found, the district court carefully laid out

the legal standards it would follow in devising a remedy.

The district court noted that in school desegregation cases

“the scope of the remedy is determined by the nature and

extent of the constitutional violation.”28 The district court

further held tha t the goal of a remedy is to prohibit new

violations and eliminate the continuing effects of prior vio

lations and tha t in fashioning remedies the court must be

guided by equitable principles.29 The district court set as its

goal the “elimination of all vestiges of state imposed segre-

27 Underfunding and the resulting deteriorated school facilities “ad

versely affect[] the learning environment and . . . discourage parents

who might otherwise enroll their children”. See Jenkins, 639 F.Supp. at

39.

28 Id. at 23 (citing Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 744 (1974) (.Milli-

ken I)).

29 Id

21

gation” using its broad equitable powers limited by:

the nature and scope of the constitutional viola

tion, the interests of state and local authorities in

managing their own affairs consistent with the

constitution, and ensuring that the remedy is

designed to restore the victims of discriminatory

conduct to the position they would have occupied

in the absence of such conduct.

Id. (citing Morrilton School District No. 32 v. United

States, 606 F.2d 222, 229 (8th Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 444

U.S. 1071 (1980)).

Guided by these principles, the district court ordered a

remedy for the pervasive effects of intentional segregation

in four stages: To remedy inferior education, a program of

educational improvements was ordered. To end racial isola

tion and attract white students back to KCMSD’s schools,

the court ordered the district to convert to a system of mag

net schools supplemented by a voluntary interdistrict trans

fer program for students in any surrounding district that

will cooperate. To repair the deteriorated physical plant, the

district court ordered a capital improvement program. And

to reverse twenty years of financial neglect and assure the

viability of the rest of the remedy, the court ordered funding

measures to enable KCMSD to finance its share of the

remedial obligations.

A. Educational Improvements to Remedy Inferior

Education

The district court designed its first remedial order to

eliminate the first of the major effects of the constitutional

violations — inferior schools — and to help eliminate the

second — racial isolation and white abandonment of the

KCMSD. That order, which this Court affirmed and ordered

fully funded, Jenkins I, 807 F.2d at 686, encompassed a

comprehensive program of educational improvements that

the district court concluded were necessary to eliminate the

22

“inferior education indigenous of the state-compelled dual

school system” in KCMSD, Jenkins, 593 F.Supp. at 1492; to

remedy the “system wide reduction in student achievement

in the schools of the KCMSD,” Jenkins, 639 F.Supp. at 24;

and to “restore the victims of discriminatory conduct to the

position they would have occupied in the absence of such

conduct [violating the constitution].” Id. at 23 (citation

omitted). The district court also found tha t regaining and

maintaining a “quality education program . . . could serve to

assist in attracting and maintaining non-minority student

enrollment.” Id. at 27.30

B. Magnet Schools to End Racial Isolation.

The district court next turned to the segregation and

white abandonment effects of the violations. Finding that

magnet schools could assist in “expanding desegregative

educational experiences” for KCMSD students, id. at 34,

the court ordered the preparation of a magnet school plan

and budget. Plaintiffs, of course, had long advocated a man

datory interdistrict remedy, in part because such a remedy

easily and inexpensively could have achieved a system of

desegregated, 25% minority schools throughout the met

ropolitan community. Because interdistrict relief was ruled

out by the district court and this Court, plaintiffs assisted

the KCMSD in the preparation of a long range magnet

30 For instance, with respect to the reduced class sizes, the district

court found that “achieving reduced class size is an essential part of any

plan to remedy the vestiges of segregation in the KCMSD” by assisting

“the KCMSD in implementing the quality education components” in the

desegregation plan and by increasing “the likelihood that the KCMSD

could maintain and attract nonminority enrollment in the future.” Jen

kins, 639 F.Supp. at 29. Similarly, the district court found that the full

day kindergarten program would both:

provide remediation to those who are victims of past segre

gation, [and] will also assist the school district in maintain

ing and attracting desegregated enrollment and providing

integrative experiences at an early age.

Id. at 31.

23

school plan believing it to be the best remaining alternative

for integrating KCMSD. Tr. September 15,1986 at 19-26, 43.

The State failed either to contribute to the KCMSD’s plan

ning process or to submit a magnet plan of its own.

Based on an extensive record the district court ordered

the “implementation of the [KCMSD’s] proposed magnet

school plan as a fundamental component of its overall

desegregation remedy,” Order, November 12, 1986 at 4, and

later found the “magnet school plan is crucial to the success

of the Court’s total desegregation plan.” Jenkins, 672

F.Supp. at 406. In two 1986 orders,31 the district court

required conversion of KCMSD by 1992 to a district in

which all students in grades 6 through 12, and about half

the students in grades K through 5, attend magnet schools.

The district court found that this systemwide conversion to

magnet schools would “serve the objectives of its overall

desegregation program,” Order, November 12,1986 at 2, and

that it was necessary to “expand[] desegregative educa

tional experiences for . . . students.” Jenkins, 639 F.Supp. at

34. In particular, the district court found tha t the plan is

desegregative,32 equitable to minorities,33 educationally

sound,34 administratively feasible,35 and economically pru

dent.36

1. Evidence Supporting F inding That The Magnet

School P lan Is Desegregative. The district court found

31 Orders, June 16,1986, and November 12,1986.

32 Order, November 12, 1986 at 3 (plan is “so attractive” it will draw

non-minority students from suburban and private schools).

33 Id. (inequity to minorities “avoided by KCMSD magnet school

plan”).

34 Id. at 4 (long-term benefit of “greater educational opportunity”

from the plan).

35 Id. at 3 (“comprehensive” plan over six years will be successful in

achieving greater desegregation).

36 Id. at 4 (costs are reasonable, benefits “worthy of such an invest

ment”).

24

that: (1) magnet schools expand desegregative educational

experiences, Jenkins, 639 F.Supp. at 34; (2) KCMSD’s plan

is “so attractive tha t it [will] draw non-minority students

from . . . private schools . . . and . . . the suburbs;” Order,

November 12, 1986 at 3; and (3) the “plan is crucial to the

success of the . . . desegregation plan” for KCMSD, Jenkins,

672 F.Supp. at 406. The court also found that the long range

magnet school plan included themes which “rated high in

the Court ordered surveys and themes that have been suc

cessful in other cities.” Order, November 12,1986 at 3. These

findings were amply supported by the evidence. Numerous

experts testified that the plan adopted by the court is

designed to desegregate the district as a whole and to elimi

nate racial segregation throughout the district. Tr. Sep

tember 15, 1986 at 95-96 (Phale D. Hale); September 16,

1986 at 222, 246-249 (Dr. Daniel M. Levine); September 17,

1986 at 598-99 (Dr. Robert A. Dentler).

As the evidence here established and this Court has

expressly recognized,37 magnet schools often do not succeed

in attracting non-minority students to inner city schools. To

maximize desegregative attractiveness, themes were chosen

carefully, then designed to assure desegregative success in

the long term through the use of sensitively crafted feeder

patterns. Tr. September 15, 1986 at 49-50; September 16,

1986 at 250-57. For instance, Southeast High School is

located in the heart of the black corridor of the district east

of Troost Street and is virtually all black. Under the long

range plan, Southeast is the last high school to be converted

fully to a magnet. The theme in this case is international

studies and foreign languages. KCMSD Ex. 2, September

15,1986, at 15. Instead of an early conversion to its theme, a

series of elementary foreign language magnets are estab

lished to attract students to foreign languages at an early

37 Liddell v. Bd. ofEduc., 801 F.2d 278, 283 (8th Cir. 1986) (.Liddell IX)

(“The plain fact is that recruitment of suburban students [to magnet

schools] will be difficult. . . ”).

25

age in schools situated in areas where they likely will draw

significant numbers of non-minority students. The plan

presumes that as those students progress through the

grades a significant proportion of them will thrive in the

foreign language theme and follow it: first to a middle

school located in the black corridor east of Troost and then,

ultimately, to Southeast High School. Tr. September 15,

1986 at 70-71.

Recent reports to the court-appointed Desegregation

Monitoring Committee38 confirm the expectations of the district

court that the magnet schools will cause substantial integration of

the classrooms of KCMSD.39

38 In its initial remedy order the district court created a Desegregation

Monitoring Committee (DMC) “to oversee the implementation of [the

desegregation] plan.” Jenkins, 639 F.Supp. at 42. The ten (later

expanded to thirteen) members consisted of three members selected

from among nine nominees each by the State, KCMSD, and the AFT

intervenor. The tenth member and chairman was appointed by the dis

trict court from among three nominees of the plaintiffs. The DMC is

charged with the “responsibility for conducting evaluations and collect

ing information and making recommendations for any modifications

concerning the implementation” of the desegregation plan. Id. Since its

establishment in 1985 the DMC has reviewed and evaluated all propos

als for magnet schools, capital improvements and modifications of the

educational improvement components of the KCMSD desegregation

plan. The DMC unanimously approved the magnet school plan and

KCMSD’s capital improvement plan, Jenkins, 672 F.Supp. at 403,

approval that, of course, included the State’s representatives on the

DMC.

39 The district court found that the “magnet plan is working as evi

denced by the large number of applications for the magnet programs

from students new to the KCMSD.” Id. at 404. See also id. at 405 (“very

likely that enrollment in the KCMSD will increase” due to the magnet

schools and other desegregation programs) and Tr, August 4,1987 at 267

(testimony that only 300 of 700 applicants from outside KCMSD could

be placed in the magnet schools to which they applied for the 1987-88

school year). Based on placements through 1987-88, all but one magnet

school met their desegregation goals, some dramatically, e.g., Central

Middle Magnet School went from 99.8% black to 86% black. A By-School

Comparison of Student Enrollment By Race and Grade for the Years

26

2. Evidence Supporting F inding That The M agnet

School P lan Is Equitable to Minorities. After prelimi

nary hearings, the district court settled upon an approach

to magnets advocated by an expert for the State who tes

tified at the preliminary remedial hearings — Dr. Dennis

Doyle. Adopting Dr. Doyle’s analysis, the district court

noted that, in some instances, magnet schools desegregate a

portion of a single district which, to integrate its classes,

seek voluntarily to move students into a few desegregated

schools. To accomplish this goal, extra resources are pro

vided to the few schools chosen to be magnets to enable the

implementation of attractive educational themes at those

schools. Half or more of the usually all black student enroll

ment is displaced to provide room for non-minority students

and, more often than not, the displaced blacks are enrolled

in segregated schools, schools tha t likely will become segre

gated, or in schools perceived to be inadequate because they

have less resources than magnets and therefore become

segregated schools. The result of such limited magnet

schools is the creation of a two-tiered system of “have” and

“have not” schools. These substantial difficulties can be

avoided only in districts with a relatively small minority

enrollment.

The district court specifically found that any such limited

approach to magnet schools in the KCMSD would be unre

sponsive to the constitutional violations found and their

particular effects:

The philosophy of a magnet school is to attract

non-minority students into a school which is pre

1986-87 and 1987-88, A Report to the Desegregation Monitoring Com

mittee, October, 1987. The 1988-89 applications to date assure additional

progress, e.g., Faxon Elementary was 100% black in 1987-88 but will be

60% black and 40% non-minority when it opens as a Montessori

Elementary Magnet School this Fall and the one elementary school

which failed to meet its goal last year, Longan French Elementary Mag

net School, will exceed both its 1987-88 and 1988-89 goals when it opens

in the Fall.

27

dominantly minority. It does so by offering a

higher quality of education than the schools which

are being attended by the non-minority students.

In each school there is a limitation as to the num

ber of students who may be enrolled. Thus, for

each nonminority student who enrolls in the mag

net school a minority student, who has been the

victim of past discrimination, is denied admit

tance. While these plans may achieve a better

racial mix in those few schools, the victims of

racial segregation are denied the educational

opportunity available to only those students en

rolled in the few magnet schools. This results in a

school system of two-tiers as it relates to the qual

ity of education. This inequity is avoided by the

KCMSD magnet school plan.

Order, November 12, 1986 at 3. In order to avoid any two-

tiered inequity, the plan ordered by the district court con

verts all nine high schools, all middle schools, and half of

the elementary schools to magnets. As a result, minority

students are given the same range of choices as are whites,

since virtually every student in the district will be allowed

to choose where to attend school. Racial equity is thus

woven into the desegregative purpose of the plan.

3. Evidence Supporting Finding That The Magnet