United States v. Hayes International Corporation Opinion

Public Court Documents

August 19, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Hayes International Corporation Opinion, 1969. 2e521576-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3f47a5b8-0a3c-478e-89a9-5244975ad150/united-states-v-hayes-international-corporation-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

r. /3

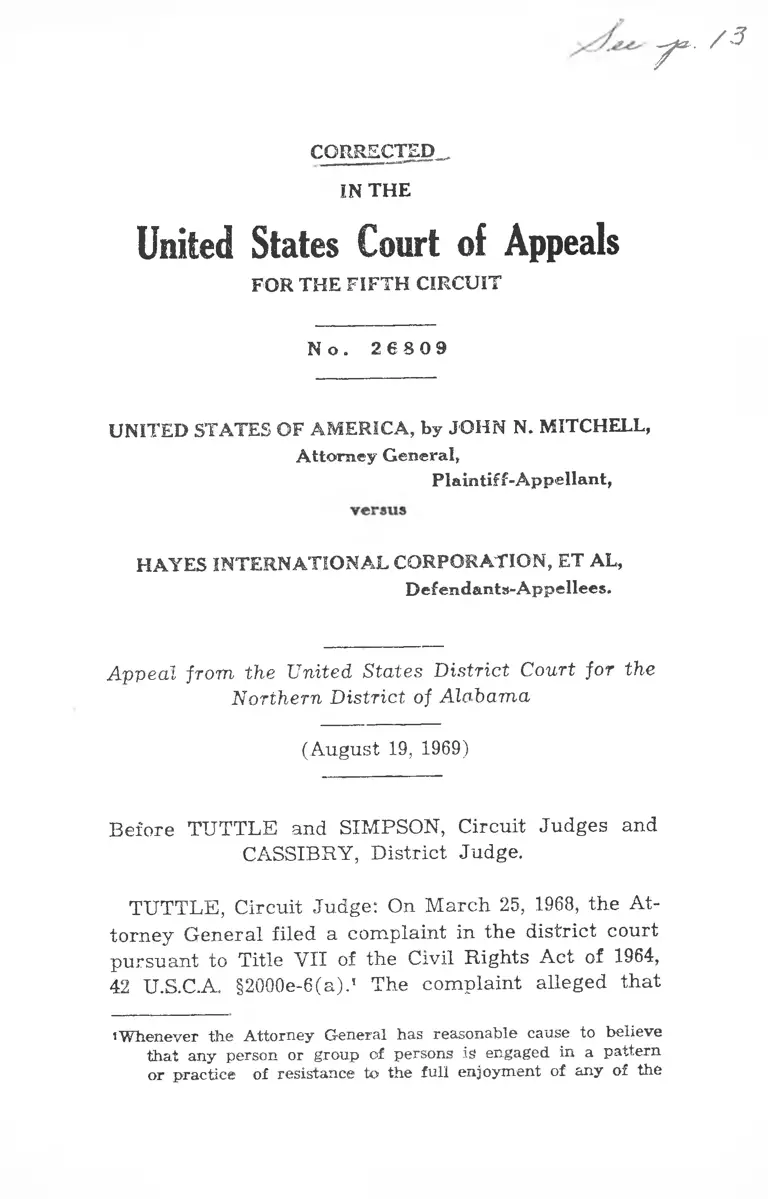

CORRECTED.^

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

N o . 2 6 8 0 9

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, by JOHN N. MITCHELL,

Attorney General,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

HAYES INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States D istrict Court fo r the

Northern D istrict of Aloham a

(A ugust 19, 1969)

B efore TU TTL E and SIM PSON, C ircu it Ju d g es and

CASSIBRY, D is tr ic t Judge,

TU TTL E, C ircu it Judge; On M arch 25, 1968, th e A t

to rn ey G en era l filed a com pla in t in th e d is tr ic t court

p u rsu a n t to T itle V II of the Civil R igh ts A ct of 1964,

42 U.S.C.A. §2000e-6(a).’ The co m p la in t a lleged th a t

iWhenever the Attorney General has reasonable cause to believe

that any person or group of persons is engaged in a pattern

or practice of resistance to the full enjoyment of any of the

2 U.S.A. V. H A Y ES IN T. CORP. E T AL

th e com pany m a in ta in ed ra c ia lly seg reg a ted divisions

and lines of p rogression ; d isc rim in a ted in its h irin g

p ra c tic e s ; and assigned w hites to jobs offering h ig h e r

pay , b e tte r ad v an c em en t and secu rity th a n s im ila rly

q ualified b lack em ployees.^ T he com p la in t req u es te d

th a t th e com pany be p e rm a n en tly en jo ined fro m con

tinu ing such violations and from failing to ta k e reaso n

ab le s teps to c o rre c t th e effects of p a s t d isc rim in a to ry

p rac tices .

The com pany re p a irs and rebu ild s a irp lan es and a ir

p lan e p a r ts la rg e ly p u rsu a n t to g o vernm en t con trac ts .

As of M arch 11, 1968 eight p e rce n t or 145 of th e com

p a n y ’s 1781 p roduction and m a in ten a n ce em ployees

w ere b lack. The jobs in th e un it w ere a r ra n g e d in

te n sen io rity divisions. E a c h division con ta ined fro m

one to seven lines of p rogression . E a c h line con tained

jobs req u irin g s im ila r job sk ills in w hich th e em ployee

could n o rm ally expect to advance as he gained ex

p e rien ce and v acan c ies occu rred . B ecause som e sen

io rity divisions con ta ined a n u m b e r of lines of p ro g res-

rights secured' by this subchapter, and that the pattern or prac

tice is of such a nature and is intended to' deny the full exercise

of the rights herein described, the Attorney General may bring

a civil action . . . requesting such relief, including an applica

tion for a permanent or temporary injunction, restraining

order . . . .

242 U.S.C.A. §2000e-2 reads:

(a) It shall be an unla-wful employment practice for

an employer—(1) to . . . discriminate against any indivi

dual with respects to his compensation terms, condi

tions, or privileges of employment, because of . .. race,

color . ; or (2) to limit, segregate or classify his

employees in any way which would deprive or tend

to deprive any individual of employment opportunities

or otherwise adversely affect his status as an em

ployee, because of such individual’s race, color. . . .

U.S.A. V. H A Y ES INT. CORP. E T A L 3

sion w hich involved s im ila r job skills, in som e cases

it w as possib le to m ove la te ra lly or u p w ard betw een

lines. F u rth e r , in case of layoff som e em ployees could

“bu m p ” less sen io r m en in th e ir p re se n t line as well

as in re la te d lines w ith in th e sen io rity division.

One h und red tw enty-tw o of the 145 b lack s w ere e m

ployed in two sen io rity divisions. M any held “C lean er”

jobs (w ash ing th e outside of a irp lan es) in sen io rity

division 7. T here w as bu t one line of p ro g ress io n in

th is division. The re m a in d e r w ere em ployed in m a in

te n an ce and ja n ito ria l jobs in division 8. F ro m a p ra c

tic a l standpoin t, th e re w as v ir tu a lly no chance to m ove

fro m th e lines of p rog ressio n con ta in ing th e p red o m

in an tly b lack jobs into th e w hite lines in th is division.

The rem a in in g b lacks w ere s c a tte re d in seven of

th e o th e r divisions. W hat th e ir jobs w ere did no t ap

p e a r in the record . H ow ever, th e com pany did con

cede th a t 138 of th e b lack em ployees w ere in “p red o m

in an tly N eg ro ” jobs.

T here w ere 13 p ay g rades. N inety-six p e rc e n t of th e

w hite em ployees w ere in th e seven h ig h est g rad es

w hile 77 p e rce n t of the b lacks w ere in th e th re e low est

g rad es . The co m p an y ’s b o a rd c h a irm a n te stif ied th a t

th e a v e ra g e an n u a l p ay of “se lec ted ” w hite em ployees

w as $7865 and of b lacks $7117.®

The collective b arg a in in g ag ree m en t gave th e com

pany b ro ad r ig h ts to fill h igh level v acan c ies w ith em -

3The sample probably was unrepresentative in that it excluded

supervisors and more whites were supervisors than blacks.

4 U.S.A. V. H A Y ES INT. CORP. E T AL

ployees who h ad less sen io rity th a n o ther em ployees

w ho m ig h t also be qualified to p e rfo rm th e work. F o r

exam ple , A rtic le IV, §17(a) p rov ided th a t th e com

p an y could tra n s fe r em ployees to any position p rov ided

only th a t th e re w ere no em ployees la id off or down

g rad ed fro m the job group of th e v aca n cy and th a t

th e person filling th e v aca n cy w as qualified.

A rtic le IV, §6(c) also p rov ided th a t in te rm s of la y

off, an em ployee holding a trad itio n a lly w hite position

in a division could bum p b lack em ployees w ith m o re

sen io rity who w ere holding low er level jobs in th a t

division.

T he com pany a p p a re n tly h ad no fo rm a l policy of

filling job v aca n c ie s fro m am ong its p re se n t b lack em

ployees even if they v/ere qualified . A t le a s t once in

th e p a s t it p rov ided b lack em ployees w ith lim ited t r a n s

fe r opportun ities bu t a t th e cost cf loss of sen io rity

and a drop in pay. The com pany could and did, how

ever, t ra n s fe r w hite em ployees into v aca n c ie s ahead

of m o re sen io r em ployees.^ T he d is trib u tio n of b lack

and w hite em ployees d em o n stra te s th a t th e com pany

chose no t to tra n s fe r b lack em ployees into w hite jobs

and v ice v e rsa even though qualified b lacks m a y have

b een av a ilab le or could have been tra in ed . W hatever

in -serv ice tra in in g p ro g ra m s w ere offered obviously

did not p rov ide b lack em ployees w ith a chance to gain

th e skills n e c e ssa ry to fill th e jobs held by w hites.

^White employee, Cecil Glenn, for example, held seven jobs in

two years. He was promoted to an “A” level job in the elec

trical field after two months with the company. He received

training in a variety of jobs thereby giving him valuable re

maining and layoffs rights.

U.S.A. V. H A Y ES INT. CORP. E T AL 5

In short, b lack em ployees p e rfo rm e d th e low est paid ,

unsk illed jobs. A lthough th e p lan t v/as opera tiv e since

1951, th e com pany a p p a re n tly \vas u n ab le to re c ru it

or tra in b lack em ployees to p erfo rm sk illed jobs ex

cep t in th e m ost token m an n er. This condition r e

m a in ed su b stan tia lly u n changed even a f te r th e effec

tive d a te of T itle V II of th e Civil R igh ts A ct of 1964.

The b lack em ployees w ere seg reg a ted in th e ir jobs

in a m a n n e r w hich deprived th em of th e opportun ity

fo r ad v an c em en t th a t w hite em ployees enjoyed.

The case in th is p o s tu re n e v e r re a c h e d th e court.

One m onth a f te r th e filing of the o rig inal com plain t,

th e A tto rney G en era l filed a m otion for a p re lim in a ry

in junction. This w as occasioned by th re e s ign ifican t

changes a t th e p lan t. F irs t, on M arch 28 th e govern

m en t aw ard ed the com pany a c o n tra c t for th e re p a ir

of KC-135 je t ta n k e rs . This c o n tra c t w ould c re a te 740

jobs, of w hich 294 would no t be filled by em ployees

w ith tra n s fe r , p rom otion or re c a ll righ ts. Second, on

A pril 8, th e com pany and union signed a new collec

tive b arg a in in g ag ree m en t w hich m ad e som e changes

in th e p rio r sen io rity divisions and in sen io rity p ro

v isions w hich would effect tra n s fe r , p rom otion, re c a ll

and layoff righ ts. Third, on A pril 12, the com pany in

s titu ted a tra n s fe r p ro g ra m w hich gave b lack em

ployees an opportun ity to tr a n s fe r to som e fo rm erly

w nite jobs.

The governm en t c o n tra c t p rov ided a unique oppor

tu n ity to p rov ide b lack em ployees w ith equal em ploy

m en t opportunities. The collective b a rg a in in g a g re e

m en t la rg e ly m erg ed th e b lack lines of p rog ression

w ith w hite lines but the com pany su b stan tia lly re ta in ed

6 U.S.A. V. H A Y ES INT. CORP. E T AL

its pow ers to tra n s fe r and p rom ote em ployees as de

sc rib ed above.

A lte r som e in itia l confusion, th e com pany ad eq u a te ly

exp la ined th e tra n s fe r p ro g ra m to th e b lack em ployees.

E a c h w as to ld to fill out an app lica tion b lan k and desig

n a te w hich five fro m am ong th e 57 av a ilab le job title s

he w as in te re s te d in tra n s fe rr in g to. They w ere g iven

a V\/eek to re tu rn th e form s. A fter the com pany m ad e

an offer, th e em ployee h ad th ree days to accept. F a il

u re to com ply w ith e ith e r ru le w as a w aiv er of rig h ts

u n d e r the p ro g ra m although in p ra c tic e th ese lim ita

tions w ere no t s tr ic tly ad h ered to. A ny em ployee who

accep ted a tra n s fe r h a d no fu r th e r r ig h ts u n d er th e

p ro g ram .

Tne p ro g ra m m a d e availab le 57 la rg e ly en try -level

job title p rev iously closed to b lacks. The re m a in d e r

of th e co m p an y ’s 140 job title s w ere no t affected.®

B ecause of th e unique opportun ites thus p re se n t to

rec tify p a s t d isc rim in a to ry p rac tice , the A tto rney G en

e ra l m oved fo r a p re lim in a ry in junction. The den ial

of th is re q u e s t is th e su b jec t of th is appeal.

The d is tric t c o u rt’s decision la rg e ly tu rn e d on th e

conclusion th a t th e tr a n s fe r p ro g ram did not v io la te

sNinety-three black employees submitted transfer requests and 47

had transferred at the time of the hearing below. Seventeen

refused offers and 23 were awaiting openings. Six were medi

cally disqualified. Of these who transferred, 18 went to General

Mechanic Beginner jobs, 12 to Sheet Metal Beginner, 11 Ma

terial Handler-Stampers and the rest were scattered in various

other entry-level positions.

U.S.A. V. H A Y ES INT. CORP. E T AL

T itle VII.® The co u rt found th a t the tra n s fe r p ro g ra m

did not v io la te th e A ct because ; (1) the b lack em ployees

who tra n s fe r re d to B eg inner positions in th e Sheet M e

ta l and G en era l M echanic lines would be p rom oted to

p e rm a n e n t “B ” level jobs d u rin g th e life of th e KC-135

co n trac t. T hey would th en be p ro tec ted ag a in s t layoff

in acc o rd an ce w ith th e ir p lan t-w ide sen iority ; (2) R e-

m aim ing p rov isions would allow w hite em ployees to

be p rom oted to h ig h e r level positions in the Sheet M etal

and G en era l M echanic lines in p re fe ren c e to m o re se

n ior b lack em ployees th en a t th e “B ” level in those

lines only in rem o te cases;^ (3) those b la ck em ployees

who chose no t to tr a n s fe r did so fo r p e rso n a l reasons,

and (4) th e p ro g ra m w as fa ir ly ad m in iste red .

6The court also noted that the collective bargaing agreement merged

the predominantly black lines of progression into white lines.

It also upgraded the wage rate^ of the Cleaner line of progres

sion and broadened the recall rights of laid-off employees.

The Court also relied in a general manner on Whitfield v.

United Steelworkers Local 2708, 263 F.2d 546 (5th Cir.), cert,

den., 360 U.S. 902 (1959), wherein it was held that a union

which in the past had negotiated discriminatory contracts was

presently only required to cease such practices and had no

obligation to remove the continuing effects of past discrimina

tion. Whitfield was not a Title VII case and therefore is not con

trolling. Furthermore, to the extent that it can be read as limit

ing the power of courts to order “such affirmative action as

may be necessary,” 42 U.S.C.A. §2000e-5(g), to simply barring

any further application of discriminatory practices, Whitfield

is inconsistent with the words of the statute, its purposes and

the thrust of recent cases in this circuit. See, e.g., Local 53,

Asbestos Workers, ------- F.2d ------- , 5 Cir., No. 24,865, Jan.

15, 1969; United States v. Local 189, United Papermakers, 282

F. Supp. 39 (E. D. La. 1968).

5'The court apparently referred to Art. IV, § 10(a) of the collective

agreement which gives first claim to a vacancy to an employee

who, without regard to seniority, had been laid off or down

graded due to a work force reduction if the employees previ

ously performed the job satisfactorily.

8 U.S.A. V. H A Y ES IN T. CORP, E T A L

i-he U nited S ta te s a rg u es th a t th e d is tr ic t c o u rt’s

v iew of th e case w as erroneous. W e ag ree .

ih e question w as not w h e th e r th e t r a n s fe r p ro g ra m

itse lf v io la ted T itle VII. The question, r a th e r , w as:

In view of th e p r im a fac ie ca se estab lish ed by th e

g o v ern m en t th a t th e com pany w as in ten tio n ally en

gag ed in a p a t te rn or p ra c tic e of re s is te n c e to th e

fu ll en joym en t of T itle V II rig h ts , did th e fa c t th a t

th e new collective b a rg a in in g ag ree m en t and th e tr a n s

fe r p ro g ra m p a r tia lly co rrec ted th e v io lations n e g a te

th e need fo r th e p re lim in a ry in junction? T h a t issue

w as no t decided by th e d is tr ic t court.

We a re m e t in itia lly by th e com pany contention th a t

th e U nited S ta tes is now a rg u in g an en tire ly new th e o ry

of the case and it should be lim ited to th e th eo ry th a t

th e tr a n s fe r p ro g ra m v io la ted T itle VII.

H ow ever, we do no view th e m a tte r th a t w ay. Of

course, if th e U nited S ta tes w ere now se ttin g fo rth

new a rg u m e n ts on fac ts n e v e r p re sen te d to th e t r ia l

cou it, th e com pany would be co rrec t. B ut is position

is Dottomed on th e fa c t th a t a fte r all th e ev idence

w as in and th e co u rt req u es te d counsel fo r bo th sides

to su m m a rize th e ir positions, gov ern m en t counsel con

c e n tra te d on th e tra n s fe r p ro g ram . T here is no doubt

abou t th a t. B ut h e also a rg u ed th e re lev an ce to h is

ca se of th e KC-135 co n tra c t and th e co llective b a rg a in

ing ag reem en t. F u rth e rm o re , he w as respond ing to

a req u es t by the tr ia l judge to d iscuss bu t one asp ec t

of the case; th e ir re p ra b le h a rm re q u ire m e n t fo r is

su an ce of a p re lim in a ry in junction.

U.S.A. V. H A Y ES IN T. CO RP. E T AL 9

I t seem s un likely th a t th e co u rt w as m isled by th e

o ra l a rg u m en t. The m otion fo r p re lim in a ry in junc

tion c lea rly s e t fo rth th e g o v ern m en t’s th e o ry as to

w hat e s tab lish ed th e p a t te rn o r p ra c tic e of re s is ta n c e

and th e im p a c t on th a t of th e changed even ts. F u r th e r

m ore , th e U nited S ta tes sought to develop de ta ils of

w hen th e com pany knew abou t th e new c o n tra c t and

w h at its job re q u ire m e n ts w ould be. W hile it is tru e

th a t th e focus of th e U nited S ta te s h e re is b ro ad e r

th a n adopted a t o ra l a rg u m en t, its b a s ic position as

show n by th e p lead ings and th e conduct of th e h e a r

ing is th e sam e, a lbeit b e tte r defined. The d is tric t court

th e whole th e o ry before it.

The com pany also a rg u es th a t in any ca se th e tr a n s

fe r p ro g ra m and new collective b a rg a in in g ag ree m en t

n eg a ted th e n eed fo r p re lim in a ry re lie f b ecau se they

p rov ided th e b lack em ployees w ith a ll th e y w ere en

title d to u n d er T itle VII. T hat, of course, is th e nub

of th e m a tte r .

B ecause th e case is before us in a p re lim in a ry pos

tu re , it is xmwise to d iscuss th e m e rits excep t in a

lim ited fashion. I t w ill be suffic ien t to b rie fly note

som e of th e w ays in w hich th e b lack em ployees still

m a y h av e been denied th e “full en jo y m en t” of th e ir

r ig h ts as p rov ided by th e law .

V7e a re not p e rsu ad ed by th e a rg u m e n t th a t th e Com

pany , fou r y e a rs a f te r th e en ac tm e n t of th e 1964 Civil

R igh ts A ct and th re e y e a rs a f te r th e effec tive da te

of T itle V II of the Act, ac ted on its own in itia tiv e and

in sritu ted th is tra n s fe r p ro g ra m fo r th e sole purpose

of ex tending to its N egro em ployees “specia l oppor-

10 U.S.A. V. H A Y ES INT. CORP. E T AL

tu m tie s” fo r tra n s fe r , tra in in g and advancem en t.

M oreover, th is C ourt w ill no t be m isled by th e “equal

paj' or su b s ta n tia l p a y ” te s t as ind ica ting th e ab

sence of ̂a v io lation of T itle VII, for T itle V II of the

19()4 Civil R igh ts A ct is not an equal p ay provision

bu t an equal opportun ity to th e full en jo y m en t of em

p loym ent righ ts.

F irst, th e tr a n s fe r p ro g ra m w as lim ited in a n u m

b er of w ays. I t covered bu t 57 of th e 140 job c lassifi

cations in th e p roduction and m a in te n a n c e unit. Y et

am ong th e b lack em ployees som e m a y h av e possessed

th e q ualifica tions to p e rfo rm jobs no t on th e p ro g ram .

Also the em ployees w ere g iven bu t one chance to tra n s -

th ey did no t acc ep t th ey w ere b a rre d from

fu r th e r r ig h ts u n d e r th e p ro g ram . The com p an y does

not a rg u e th a t it w as a d m in is tra tiv e ly im possib le to

ex tend its duration . T here m a y be n o n tra n s fe rr in g em -

p loyees who now see th a t th e com pany w as co rre c t

w hen i t a s su re d th em th a t no d ire consequences would

follow a tr a n s fe r and who now w ould like to be con

sidered .

Second, th e em p loym en t s ta tis tic s d iscussed , sup ra ,

pp 1-2, am p ly d em o n stra ted a p re lim in a ry show ing

th a t th e com pany h irin g p ra c tic e s v io la ted T itle VII.

Y e t the h irin g p ra c tic e s w ere no t affected by th e tr a n s

fe r p ro g ra m or th e co llective b a rg a in in g ag reem en t.

T hird , th e co llective b a rg a in in g a g re e m e n t s till g ives

th e com pany un lim ited pow er to tra n s fe r em ployees

from one p e rm a n e n t position to an o th e r su b je c t only

to the lim ita tio n th a t th e re a re no em ployees la id off

o r dow ngraded from th e job in w hich th e v aca n cy ex

ists.

U.S.A. V. H AY ES INT. CORP. E T AL 11

I t is m ost d ifficult to u n d e rs tan d w hy a com pany

sucn as H ayes w hose collective b a rg a in in g ag ree m en t

g ives th e un lim ited rig h t to th e em ployer to t r a n s

fe r its employees® would find a n eed fo r a “ specia l

t ra n s fe r p ro g ra m ” for its N egro em ployees w here th e

p re req u is ite s , v aca n cy and qualifica tion , u n d er both

p rov isions a re th e sam e. A bsen t any ju stifiab le reason ,

w hich does not ap p e a r in e ith e r the appellees’ b rie f

o r in th e R ecord , the log ical rea so n in ligh t of all

th e fac ts p re sen te d w ould be race .

F ou rth , a lthough the d is tr ic t co u rt found th a t r e

m an n in g provisions would p rov ide only th e rem o te pos

sib ility of filling a job w ith a le ss sen io r w hite em

ployee in p re fe ren c e to an equally qualified b lack , the

find ing w as lim ited to th e s itu a tio n c re a te d by the

tr a n s fe r p ro g ram . H ow ever, in o ther c irc u m stan c es

th e possib ility still ex ists th a t a qualified b lack em

ployee would be denied a chance to fill a job b ecause

a less sen ior w hite em ployee h ad su p erio r (rem an n in g )

rig h ts denied the b lack b ecause of race . F o r exam ple,

if a w hite em ployee h ad held a position a t or n e a r

th e top of a line of p rog ressio n and b ecau se of ra c e

b lacks h ad been excluded from th a t position (such m ay

be the case even un d er the tra n s fe r p ro g ram ) and

th ro u g h rem a n n in g th e w hite em ployee is in a low er

ra te d job w ithin the sen io rity division, he w ill fill a

v aca n cy in the h ig h e r ra te d job in p re fe ren c e to b lack

en ip loyees equally qualified and w ith m o re sen io rity

sThe Company may transfer an employee permanently or temporari

ly from one job group seniority division to another, provided

only that if the transfer is permanent, there are no employees

laid off or downgraded from the job group to which he is being

transferred. (Art. IV § 17(a) ).

12 U.S.A. V. H A Y ES IN T. CORP. E T AL

even though both em ployees a re p re sen tly p e rfo rm

ing th e sam e job. The p re se n t p re fe ren c e fo r th e w hite

c a n only be explained on th e b asis of H ay es’s long

es tab lish ed p ra c tic e s of ra c ia l d isc rim in a tio n in em

p loym en t and hence would v io la te T itle VII.

F ina lly , th e p re sen t app lica tion of layoff r ig h ts

gained by w hites bu t denied to b lacks in the p a s t could

also re su lt in a T itle V II v io lation in a m a n n e r s im ila r

to chat d iscussed above re la tiv e to the rem a n n in g p ro b

lem .

U nder th e tr a n s fe r p ro g ram , a N egro em ployee

would only be allow ed to tra n s fe r if he qualified and

th e re ex isted a v acan cy . A v aca n cy would ex ist only

a f te r all em ployees w ith rem a n n in g rig h ts or re c a ll

r ig h ts u n d er th e layoff pool a r ra n g e m e n t h ad ex erc ised

th e rig h t or w aived th e right.®

As a p ra c tic a l m a tte r , in m ost cases th is w ould m e a n

th a t a w hite em ployee w ith less sen io rity th a n a N egro

em ployee p a rtic ip a tin g in the tra n s fe r p ro g ra m would

get f irs t p re fe ren c e to jobs w hich n e ith e r h ad fo rm erly

held and fo r w hich bo th w ere equally qualified.

9A11 employees who were on March 29, 1968 in Seniority Division

VII or held jobs of Janitor, Boiler Tender, Facility Mainte

nance Man, Automotive Maintenance Man or Cement Finisher

and Plasterer in Seniority Division VIII, as defined in the

Hayes— UAW Agreement dated April 1, 1965, shall be given,

before new employees are hired, a single opportunity to trans

fer in accordance with their seniority to any beginning or entry

level job in any Seniority Division for which tfiey are qualified

to fill vacancies in such job existing after all employees have

exercised their seniority and other rights under the collective

bargaining agreement. (A.98).

U.S.A. V. H A Y ES INT. CORP. E T AL 13

Thus it is c lea r th a t the tra n s fe r p ro g ra m and col

lec tiv e b a rg a in in g a g ree m en t did not p rov ide th e fu ll

v ind ica tion of the T itle V II r ig h ts to w hich th e em

ployees w ere entitled .

'th is am p ly d em o n stra te s th e req u is ite show ing th a t

th e U nited S ta tes v/ould p rev a il on th e m e rits . A pre-

vasiv e p a tte rn of d isc rim in a to ry em p loym en t p ra c

tices w as dem o n stra ted . A g ainst th is background , the

tra n s fe r p ro g ra m and collective b arg a in in g ag ree m en t

p rov ided only a p a r tia l co rrec tio n of p a s t illeg a l a c

tions. The re m a in in g p a tte rn and p ra c tic e s rem ained .

The appellee chooses to believe th a t th e “sing le u lti

m a te issu e” on th is ap p ea l is w hether th e d is tr ic t court

abused its d iscre tion in no t g ran tin g th e ap p e llan t’s

m otion for p re lim in a ry in junction . This contention

should also be p laced to re s t. The t r ia l ju d g e should

h av e g ran te d th e ap p e llan t’s m otion fo r p re lim in a ry

in ju n c tio n .,jt is tru e th a t th is cou rt has follow ed th e

v iew th a t an in junction does no t follow as a m a tte r of

course upon e ith e r a finding or s tipu la tion of v io lation

of som e A ct of C ongress. M itchell v. Ballenger Paving

Company, Inc., 229 F.2d 297, 300 (5th Cir., 1962). How

ever, it is equally tru e th a t th is co u rt h a s consisten tly

held th a t th e decision of th e low er co u rt is su b jec t to r e

view and w here it is c le a r th a t its d iscre tion h as not

been ex erc ised w ith an eye to th e pu rpose of th e Act,

W irtz V. B. B. Saxon Company, 365 F.2d 467, 462 (5th

Cir., 1966); Shultz v. P a rk e ,------ F.2d-------(5th Cir., 1969),

or exerc ised in ligh t of th e objective of th e act, M itchell

V. Ballenger Paving Company, Inc., su p ra , w e h ave

n ev erth e less no t h es ita ted to re v e rse an o rd e r of the

t r ia l cou rt denying an in junction w ithout th e need of

a d iscussion of abuse and d iscretion.

14 U.S.A. V. H A Y ES INT. CORP. E T AL

W here, as here , th e s ta tu to ry rig h ts of em ployees

a re involved and an in junction is au tho rized by s ta

tu te ’® an d th e s ta tu to ry conditions a re sa tisfied as in

th e fac ts p re sen te d here , th e u su a l p re req u is ite of ir

re p a ra b le in ju ry need not be e s tab lish ed and th e a-

gency to w hom the en fo rcem en t of th e rig h t h as been

e n tru s te d is no t req u ired to show ir re p a ra b le in ju ry

before ob ta in ing an in junction. Flem ing v. Salem Box

Co., 38 F. Supp. 997, 998-99 (D. Ore., 1940); W estern

Electric Co., Inc. v. C inema Supplies, Inc., 80 F . 2d

106, 56 S. Ct. 595, 297 U.S. 717 (c e r t D en.). We tak «

th e position th a t in such a case, ir re p a ra b le in ju ry

should be p re su m ed from the v e ry fa c t th a t th e s ta tu te

h as been v iolated . W henever a qualified N egro em

ployee is d isc rim in a to rily den ied a chance to fill a

position fo r w hich he is qualified and h as th e sen io rity

to obtain, he su ffers ir re p a ra b le in ju ry and so does

th e la b o r fo rce of th e coun try as a whole.

M oreover, we hold as did th e co u rt in Vogler v. M c

Carty, Inc., 294 F . Supp. 368, 372 (E.D . La. 1967) af

f irm ed ____ F.2d___ (5th Cir., 1969) th a t w here an e m

p loyer h a s engaged in a p a tte rn and p ra c tic e of dis

c rim in a tio n on account of race , etc., in o rd e r to in

su re th e full en joym ent of th e r ig h ts p ro tec ted by T itle

V lf of th e 1964 Civil R igh ts Act, a ffirm a tiv e and m a n

d a to ry p re lim in a ry re lie f is requ ired .

Io§707(b) Civil Eights Act of 1964 2000e-6(b) — The Attorney

General is authorized .. . requesting such relief including an

application for a permanent or temporary injunction or re

straining order or other against the person or persons responsi

ble for such pattern or practice as he deems necessary to in

sure the full enjoyment of the rights described herein.

U.S.A. V. H A Y ES INT. CORE. E T AL 15

As th e cou rt in Quarles v. Philip M orris, Inc., 279

F.Supp. 505, 516 (E.D . Va. 1968) concluded, “C ongress

did not in tend to freeze an en tire g en era tio n of N egro

em ployees in to d isc rim in a to ry p a tte rn s th a t ex isted

before th e A ct; we add th a t n e ith e r did C ongress in tend

fo r an en tire g en era tio n of N egro em ployees to be given

a one chance lim ited opportim ity u n d e r th e guise of

“specia l oppo rtun ities” to b re a k th e d isc rim in a to ry

p a t te rn w hich m ig h t ex ist a t a com pany .”

It w as e r ro r to re fu se to issue th e p re lim in a ry in

junction. The case is R E V E R S E D and REM A N D ED

fo r fu r th e r p roceed ings not in co n sisten t w ith th is opin

ion.

Adm. Office, U.S. Courts—Scofields’ Quality Printers, Inc., N. O., La.