Craven v. Carmical Petitioner's Reply to Respondent's Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Craven v. Carmical Petitioner's Reply to Respondent's Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1972. 66282197-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3fa41ab1-fd88-4bf9-af81-7cc6bc1f1a12/craven-v-carmical-petitioners-reply-to-respondents-brief-in-opposition-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

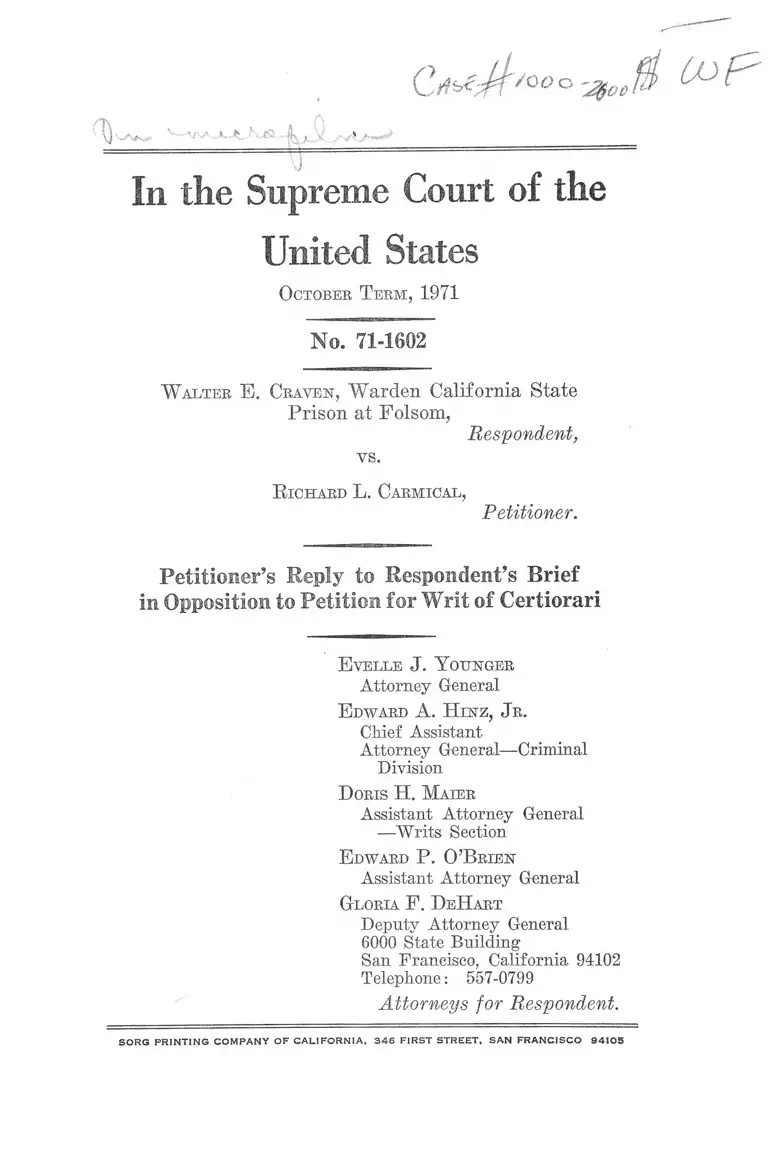

In the Supreme Court of the

United States

October T erm, 1971

No. 71-1602

V ....^ ....^ >-* 5 ■ /■ - /» J h ~ « >

W alter E. Craven, Warden California State

Prison at Folsom,

Respondent,

vs.

R ichard L. Cabmical,

Petitioner.

Petitioner’s Reply to Respondent’s Brief

in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari

E velle J. Y ounger

Attorney General

E dward A. H inz, J r.

Chief Assistant

Attorney General— Criminal

Division

D oris H. Maier

Assistant Attorney General

— Writs Section

E dward P. O’Brien

Assistant Attorney General

Gloria F. D eHart

Deputy Attorney General

6000 State Building

San Francisco, California 91102

Telephone: 557-0799

Attorneys for Respondent.

S O R G P R IN T IN G C O M P A N Y O F C A L IF O R N IA , 3 4 6 F IR S T S T R E E T , S A N F R A N C IS C O 9 4 I O S

SUBJECT INDEX

Page

Preliminary Statement...................................................... 1

I. Review of Certiorari Is Appropriate at This Time 1

II. The Question of When Deliberate By-Pass of a

Valid State Procedural Rule Precludes Habeas

Corpus Relief Is an Important One Which Should

Be Considered and Decided by This Court.........- 3

III. The Decision Below Incorrectly Applied the

Standards Established by This Court............... — 6

Conclusion.....................................................-.................... H

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases

Pages

Carter v. Jury Commission, 396 U.S. 320 (1970) ....... 9

Donaldson v. California, 404 U.S. 968 (1971) .............. 8

Fay v. New York, 332 U.S. 261 (1947) ..................... 7

Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1963) ............................... 4

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969) 7, 8, 9

Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 401 U.S. 424 (1971)..7, 8,10

Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400 (1942) ................................. 5

Humphrey v. Cady, 405 U.S. 504 (1972) ........... ........ 4

Jefferson v. Hackney, 32 L.Ed. 285 (1972) ................ 8,10

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938) .................... . 4

Lattimore v. Craven, 453 F.2d 1249 (9th Cir. 1972)..... 2

McMann v. Richardson, 397 U.S. 759 (1970) ........... . 4

People v. Jones, 25 Cal.App.3d 776, 102 Cal.Rptr. 277

(1972)............................................................................ 3

Peters v. Kiff, 33 L.Ed.2d 83 (1972) ......................... . 4, 5

People v. Newton, 8 Cal.App.3d 359, 87 Cal.Rptr. 394

(1970).... 6

People v. Sylvester, 3 Crim. 6488 (Sacramento) ............ 3

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970) ........... 9

Statutes

Title VII, Civil Rights Act of 1964:

Section 703(a) ............................................................. 8

Section 703(h) ............................................................. 8,9

In the Supreme Court of the

United States

October T erm, 1971

No. 71-1602

W alter E. Craven, Warden California State

Prison at Folsom,

Respondent,

vs.

R ichard L. Carmical,

Petitioner.

Petitioner’s Reply to Respondent’s Brief

in Opposition to Petition for W rit of Certiorari

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

Respondent’s Brief in Opposition to the Petition for

Writ of Certiorari, in addition to presenting argument on

the issues raised in the petition sets forth in an “ Introduc

tion” arguments which he asserts militate against granting

the petition. We respond first to the contentions raised in

this introduction, and then to the arguments made.

I

REVIEW BY CERTIORARI IS APPROPRIATE AT THIS TIME

Respondent advances three points alleged to militate

against the granting of the petition: 1) that the ease was

remanded for a hearing to prove or disprove the facts

alleged; 2) that the “clear thinking” test at issue is no

longer in use in Alameda County and accordingly does not

present an important problem in the administration of

2 :

justice; and 3) that the state’s claim as to the impact of the

decision is wholly speculative. We disagree with respond

ent’s characterization of the case and submit that review at

this time will prevent the development of significant prob

lems in the administration of justice and the needless waste

of time in the increasingly crowded state and federal

courts.

It is of course true that the facts as developed at a hear

ing in the District Court on remand may prove to be dif

ferent than those alleged in the petition. However, if, as

the District Court found and as petitioner has urged in

this Court, the facts alleged in the petition do not demon

strate that the jury panel was unconstitutionally selected,

return of this case for an evidentiary hearing would result

in a totally unwarranted waste of limited judicial resources.

Moreover, if the facts developed at a hearing do in fact dis

prove the allegations of the petition, the states comprising

the Ninth Circuit are left with a decision which establishes

what is in our view a totally erroneous statement of the

law and its application to the jury selection process, or at

least, with conflicting statements of the applicable standard.

Compare Lattimore v. Craven, 453 F.2d 1249,1251 (9th Cir.

1972).

Respondent has claimed that the case has no significance

because the test at issue was discontinued in 1968, and the

state’s claim of retrials in the hundreds is speculative. We

submit that the potential impact of this interpretation of

the criteria for jury selection is enormous because it may

require not only retrials in Alameda County, but is totally

retroactive and applicable throughout the Ninth Circuit.

We do not know how many counties in California or states

in the Ninth Circuit utilize “ intelligence” tests. However,

challenges to such tests on the basis of disproportionate

representation have been made in Los Angeles County, the

most populous in California, and in Sacramento County.1

Finally, the case in its present posture raises a signi

ficant issue of deliberate by-pass—the extent to which

federal courts should inquire into the motives and knowl

edge of counsel years after the event where there is no

question of the fairness of the trial or the justice of the

result.

We submit that this case raises issues of significance

which should be determined by this Court at this time, and

that further proceedings in this case, and in the others

which will inevitably be filed should certiorari be denied,

will unnecessarily burden both state and federal judicial

systems.

3

II

THE QUESTION OF WHEN DELIBERATE BY-PASS OF A VALID

STATE PROCEDURAL RULE PRECLUDES HABEAS CORPUS

RELIEF IS AN IMPORTANT ONE WHICH SHOULD BE CON

SIDERED AND DECIDED BY THIS COURT

In his state court trial, respondent Carmical raised no

question concerning the racial composition of the jury

panel from which the jury which tried him was selected.

For the reasons stated in our petition, we take the position

that Carmical’s failure to challenge the panel before trial

in accordance with state procedure precludes granting

relief on federal habeas corpus, without further inquiry

into counsel’s or respondent’s reasons, at least in cases

where there is no credible claim of incompetence of counsel.

Respondent in opposing the petition for writ of certiorari

on this question asserts that the decision below Avas correct

because the state did not “ fulfill its burden of demonstrat

1. See, Donaldson v. California, 404 U.S. 968 (1971) ; People

v. Jones, 25 Cal.App.3d 776, 102 Cal.Rptr. 277 (1972); People v.

Sylvester, 3 Crim. 6488 (Sacramento).

4

ing an affirmative, intelligent waiver of known constitu

tional rights . . . citing Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458

(1938), and Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1963), and two

recent cases decided by this Court: Humphrey v. Cady, 405

U.S. 504 (1972); Peters v. Kiff, 33 L.Ed.2d 83 (1972).

(Brief at 7-8.)

In Humphrey v. Cady, the defendant had raised constitu

tional questions concerning the Sex Crimes Act in the state

court proceedings, but the defendant’s counsel failed to

file a brief on the questions as requested by the trial judge.

When counsel failed to act, the court concluded that the

state petition was sufficient to support the order continuing

confinement. No appeal was taken from the order. The

District Court concluded that the failure of counsel to file

a brief amounted to a deliberate strategic decision to

abandon the constitutional claims and barred federal

relief. On these facts, this Court held that a hearing was

necessary to determine the reason for counsel’s failure to

file a brief and the extent of the defendant’s participation.

This Court noted that a defendant is not necessarily bound

by counsel’s decision.

We submit that in the instant case different circum

stances require a different result, and that despite the use

of the “knowing and intelligent waiver” standard in

Humphrey, failure properly to challenge a jury should pre

clude federal habeas corpus relief without further inquiry

as to the reasons.

This Court’s use of the “knowing and intelligent waiver”

standard in Humphrey cannot logically or even usefully

be extended to all trial decisions which involve constitu

tional rights;2 both the burden on the courts and the

2. Inquiry into motivation must end somewhere. Cf., McMann

v. Richardson, 397 U.S. 759, 768-69 (1970). In McMann, this Court

held that a counseled defendant was not entitled to a hearing on

his allegation that his plea of guilty was motivated by a coerced

potential for disrupting the administration of justice are

too great. Are we, for instance, to have a federal judicial

inquiry into the motives and knowledge of counsel who fail

to cross-examine a witness or who do not call a possible

witness? Are we to conduct, years later, a federal court

hearing to determine whether a defendant made a “knowing

and intelligent waiver” of his right to testify or his right

not to testify ?

Respondent points out that in Peters v. Kiff, supra, this

Court upheld a habeas petitioner’s claim of systematic

racial exclusion even though the claim was not raised at

trial. We note that the opinions constituting a majority in

that case did not discuss the issue of deliberate by-pass, so

apparently it was not raised as an issue in the case. It was

pointed out in the dissenting opinion, however, that Hill v.

Texas, 316 U.S. 400 (1942) on which Mr. Justice White’s

concurring opinion relied, was expressly limited to cases

where timely objection had been made. 33 L.Ed.2d at 99

(fn). Since the question was not ruled on, the case does not

preclude consideration of the question here. Moreover, in

Peters, the Court was establishing a new rule of standing

which at least provided a reason for reaching the issue

despite the doctrine of deliberate by-pass. In the instant

case, respondent insists that the rule applied by the Court

of Appeal is not a new rule; thus, there is no reason for

setting aside valid state procedural rules.8 3

confession. This Court considered his plea a “ plain by-pass” of

state remedies in regard to testing the confession and commented

that whether it was intelligent depended on whether he was so

incompetently advised by his counsel he should be afforded another

chance. There has been no claim of incompetent counsel here.

3. It is our position that the Court of Appeal incorrectly inter

preted the existing law while purporting to follow it, thus, in effect

establishing a new rule. If this Court does establish a different

standard, it should be prospective only, in accordance with Peters.

As pointed out in our petition, no legitimate interest of

a criminal defendant is protected by permitting collateral

attack on federal habeas corpus where he has failed to

raise the issue at the proper point in the trial process. The

state, however, has a compelling interest in the finality of

trials which have been fairly conducted with a jury satis

factory at the time. We submit that the reasons which

dictate the use of the “knowing and intelligent waiver”

standard in appropriate cases do not apply here and no

legitimate interest of the defendant is protected by apply

ing it.

6

I l l

THE DECISION BELOW INCORRECTLY APPLIED THE

STANDARDS ESTABLISHED BY THIS COURT

Respondent urges that the decision below is not in con

flict with decisions of this Court and that the state’s posi

tion that the case improperly applied decisions of this

Court is based on a semantic quibble over the word “ objec

tive” (Brief at 9-10).

The state does not contest the proposition that the statis

tics presented by Carmical below were sufficient to make

out a prima facie case of jury discrimination based on the

cases decided by this Court.4 However, these statistics were

not the only information presented to the court. The peti

tion showed that the disproportion was due to an objective

test of 25 questions which was given to all prospective

jurors. While respondent’s brief states that “ the test was

culturally biased so that blacks would fail it in greater

4. We note, however, that the “ statistics” presented to the

District Court and to this Court (Brief at 5) also showed that of

47 jurors chosen from the two selected districts in 1966, the year

of Carmical ’» trial, 6 were Negroes, a percentage of 12.8. As of

1968 Nevroes constituted 12.4 of the county population. See,

People v.N ewton, 8 Cal.App.3d 359, 389, 87 Cal.Bptr. 394, 414

(1970).

proportions than whites” (Brief at 11), this is not supported

by any allegation in the petition. In his testimony and affi

davit, the psychologist concluded that the test must measure

something other than average intelligence because it was

difficult to come to the conclusion that such a high per

centage of non-whites were below average. The possible

reason given was that some questions (20, 21 and 25) had a

“ cultural bias” and could account for the difference. It was

the opinion of the psychologist that the test was made up

without considering cultural differences. Thus, there is

nothing to support the statement that the test was biased

“ so that” blacks would fail it. The test was before the courts

below and is before this Court. It is obviously racially

neutral. Even if it is “ culturally biased,” whatever that

may mean, that does not make it unconstitutional. Any jury

panel must deal with problems and issues couched in. the

language and values of the prevailing culture. There is no

constitutional requirement that tests to screen jurors must

be so phrased that proportional percentages of various

groups are chosen. Indeed, this Court has held directly to

the contrary. See, Fay v. New York, 332 U.S. 261 (1947).

We also note that respondent’s and the psychologist’s other

criticisms of the test—that it was too short, that the pass

ing grade was too high, and that a time notice should have

been given—apply equally to everyone taking the test.

While these factors may have made the selection process

imperfect, again, it was completely “ racially neutral.”

Respondent urges that the decision below

“comes squarely within the rationale of Griggs v.

Duke Power Company, 401 U.S. 424 (1971), and

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969),

holding invalid tests or other selection methods that

serve no valid purpose and that have a racially dis

criminatory impact, regardless of the intent behind

their use.” (Brief at 11.)

7

He then urges that the test for jury discrimination should

be no less stringent than for job discrimination, citing, to

buttress this conclusion, Jefferson v. Hackney, 32 L.Ed. 285

(1972). Neither Origgs nor Gaston applies to this case, and

Jefferson provides support for the state’s position herein.

In Griggs, this Court indicated that it granted review

“ to resolve the question whether an employer is

prohibited by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII,

from requiring a high school education or passing of a

standardized general intelligence test as a condition

of employment in or transfer to jobs when (a) neither

standard is shown to be significantly related to success

ful job performance, (b) both requirements operate to

disqualify Negroes at a substantially higher rate than

white applicants, and (c) the jobs in question formerly

had been filled only by white employees as part of a

longstanding practice of giving preference to whites.”

Section 703(a) of the Civil Rights Act provides inter alia

that it shall be an unlawful practice for an employer to

classify his employees in ways to adversely affect his status

because of Ms race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

Section 703(h) provides that is is not unlawful to give or

act on the results of a professionally developed ability test

provided the test “ is not designed, intended or used to dis

criminate because of race, color, religion, sex or national

origin.”

The Court in Griggs was concerned solely with interpret

ing the meaning of the Act. The Court noted that the objec

tive of Congress was to achieve equality of job opportuni

ties and remove past barriers:

“Under the Act, practices, procedures or tests neutral

on their face, and even neutral in terms of intent can

not be maintained if they operate to ‘freeze’ the status

quo of prior discriminatory employment practices

What is required by Congress is the removal of arti-

8

fieial, arbitrary, and unnecessary barriers to employ

ment when the barriers operate invidiously to dis

criminate on the basis of racial or other impermissible

classification . . . . The Act proscribes not only overt

discrimination but also practices that are fair in form

but discriminatory in operation. The touchstone is

business necessity. If an employment practice which

operates to exclude Negroes cannot be shown to be

related to job performance, the practice is ‘prohibited.’

Id. at 4319.

The Court then went on to discuss the meaning of section

703(h) authorizing test not “ designed, intended or used to

discriminate . . (Emphasis added by Court). The Court

noted that the Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion, with enforcement responsibility, had issued guidelines

interpreting this section to permit only the use of job

related tests. The Court then reviewed the legislative his

tory of the Act and concluded that the guidelines expressed

the will of Congress. Id. at 4320-21.

Thus, the decision is based entirely on statutory con

struction and not on constitutional requirements. We sub

mit that such a decision interpreting a statute and related

to the entirely different problems of employment is entirely

inapplicable to the instant ease. There is no constitutional

violation in a jury selection process unless intentional dis

crimination on grounds of race is shown. The Griggs ease

does not change in any way the position of the Court

expressed in Carter v. Jury Commission, 396 U.S. 320

(1970) and Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970).

Gaston involved the interpretation of the Voting Eights

Act of 1965 which suspended the use of any test or device

as a prerequisite to registering to vote in a jurisdiction in

which less than 50% of the voters were registered. The

burden was on the jurisdiction to rebut the presumption of

9

discrimination. The court concluded that it was appropriate

to consider whether a test had the effect of denying the

right to vote because the jurisdiction had maintained sepa

rate and inferior schools.

Respondent cites Jefferson in support of his argument

on the basis that this Court distinguished Griggs not on

grounds of statutory interpretation but on grounds that

the Griggs test had no legitimate purpose while the Texas

statute in Jefferson served a reasonable supportable pur

pose of the state. Thus, his argument continues, the present

case is within Griggs because the clear-thinking test served

no legitimate function (brief at 11, note 8). Respondent

not only misapprehends Jefferson, but misstates the “ facts”

in the instant case.

First, there is nothing in the record before this Court

to establish by allegation or otherwise that the test in

question served “no legitimate function whatever.” The

function of the test was to select jurors of ordinary intelli

gence pursuant to California statutes. That it did this less

than perfectly does not make it constitutionally deficient.

Second, in Jefferson, this Court declined to find invidious

discrimination in the unequal reduction of benefits among

AID classes merely because there was a larger percentage of

Negroes and Mexican Americans in the class with the

greatest reduction, where there was no intent to discrimi

nate in establishing the reductions. "While Jefferson in

volved the distribution of benefits and the interpretation

of the Social Security Act and thus had no necessary appli

cability to the jury discrimination problem, it does stand

for the proposition that disparity in racial percentages

absent a showing of intentional discrimination does not

constitute a violation of equal protection.

We submit that the use of the test at issue here, even if

it was imperfect, did not violate constitutional standards

1 0

and that the decision of the court below was clearly erro

neous and in conflict with decisions of this Court.

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, we respectfully submit that the

petition for Writ of Certiorari be granted.

Dated: October 4, 1972

1 1

E velle J. Y ounger

Attorney General

E dward A. H inz, Jr.

Chief Assistant

Attorney General— Criminal

Division

D oris H. Maier

Assistant Attorney General

—"Writs Section

E dward P. O’Brien

Assistant Attorney General

Gloria F. D eH art

Deputy Attorney General

Attorneys for Respondent.