Vulcan Society of New York City Fire Department, inc. v. Civil Service Commission of the City of New York Brief of Plaintiffs as Appellees and Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Vulcan Society of New York City Fire Department, inc. v. Civil Service Commission of the City of New York Brief of Plaintiffs as Appellees and Appellants, 1973. 89ec9b22-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3fc533f7-bc98-4cb9-b736-835ffb529dd9/vulcan-society-of-new-york-city-fire-department-inc-v-civil-service-commission-of-the-city-of-new-york-brief-of-plaintiffs-as-appellees-and-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

S T

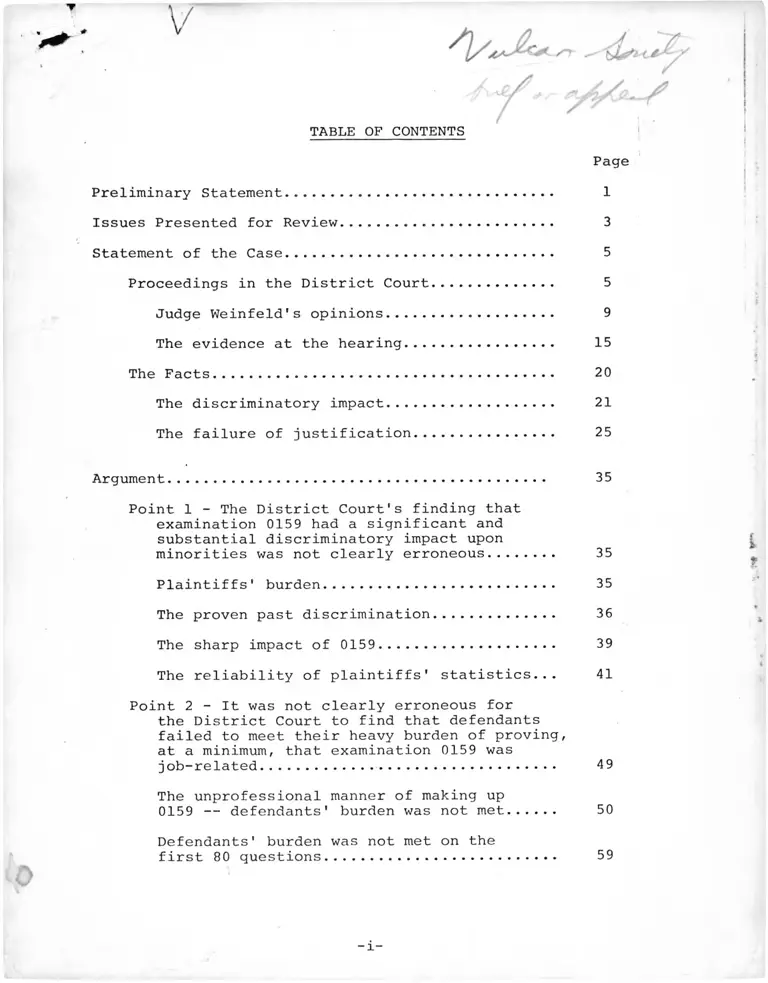

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Preliminary Statement............................. 1

Issues Presented for Review...... ................. 3

Statement of the Case............................. 5

Proceedings in the District Court............. 5

Judge Weinfeld's opinions.................. 9

The evidence at the hearing................ 15

The Facts..................................... 20

The discriminatory impact.................. 21

The failure of justification............... 25

Argument......................................... 35

Point 1 - The District Court's finding that

examination 0159 had a significant and

substantial discriminatory impact upon

minorities was not clearly erroneous....... 35

Plaintiffs' burden......................... 35

The proven past discrimination............. 36

The sharp impact of 0159................... 39

The reliability of plaintiffs' statistics... 41

Point 2 - It was not clearly erroneous for

the District Court to find that defendants

failed to meet their heavy burden of proving,

at a minimum, that examination 0159 was

job-related................................ 49

The unprofessional manner of making up

0159 -- defendants' burden was not met..... 50

Defendants' burden was not met on the

first 80 questions.................. 59

Page

The lack of a competitive physical

-- strong evidence of defendants'

failure to carry their burden................. 62

Point 3 - Judge Weinfeld's interim relief

remedy is not excessive and, in fact,

falls short of the relief he should

have ordered under all the "equities";

a remand there should be on this point,

but only to establish a 1-to-l ratio

of appointments............................... 67

Rebutting Intervenors ' points................. 68

As to the JRC' s contentions................... 71

Our position as appellants.................... 72

Point 4 - The District Court erred in not finding

that defendants' minimum height require

ment for firemen discriminates against

Hispanics and is not job-related or, in

the alternative, the Court erred in refusing

plaintiffs a hearing on this issue............ 75

The facts..................................... 75

The District Court's erroneous evasion......... 78

The merits.................................... 79

The denial of a hearing....................... 83

Point 5 - The District Court erred in not finding

that defendants' high-school diploma re

quirement for firemen and their automatic

disqualification of candidates with criminal

convictions discriminate against minorities

and are not job-related or, in the alternative,

the Court erred in refusing plaintiffs a

hearing on these issues....... 84

The high school diploma requirement........... 85

The disqualification for criminal

convictions................................... 87

The standing of plaintiffs as

class representatives........................ 90

Plaintiffs' right to a hearing............... 94

Conclusion.................. -................ 95

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Aguayo v. Richardson, 473 F.2d 1090

(2d Cir. 1973) ................................... 94

Arrington v. Massachusetts Bay

Transportation Auth., 306 F.Supp.

1355 (D. Mass. 1969) ....................... 39, 40, 91

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc, v .

Bridgeport Civil Service Comm'n,

354 F.Supp. 778 (D. Conn. 1973),

aff'd, dkt. no. 73-1356, slip opin.

No. 894, 2d Cir. June 28, 1973 ....... 35-37, 39-41, 48

54, 63, 71-74

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 330

F.Supp. 203 (S.D. N.Y. 1971),

aff'd, 458 F .2d 1167 (2d Cir. 1972) ... 12, 35-42, 45-4955-58, 65, 94

Carr v. Conoco Plastics, Inc., 423

F.2d 57 (5th Cir.), cert, denied,

400 U.S. 951 (1970) ............................... 94

Carter v. Gallagher, 3 CCH Emp.

Prac. Dec. 118205 (D. Minn.),

modified, 452 F.2d 315, 327 (8th

Cir. 1971) (en banc), cert, denied,

406 U.S. 950 (1972) ................. 37, 47, 73, 86-91

Castro v. Beecher, 334 F.Supp. 930

(D. Mass. 1971), aff'd in part and

rev'd in part, 459 F.2d 725 (1st

Cir. 1972) .................... 38, 39, 41, 48, 49

56, 73, 86, 91

Page

Davis v. Washington, 348 F.Supp.

15 (D.D.C. 1972) ............................... 39

Fowler v. Schwarzwalder, 351 F.Supp.721, (D. Minn. 1972) ................. 38, 40, 51, 52

Gregory v. Litton Systems, Inc.,

316 F.Supp. 401 (C.D.aff1d , 5 CCH Emp. Prac., Dec.

118089 (9th Cir. 1972) ....................... 81, 87

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S.

424 (1971) .................................. 81, 86

Hall v. Werthan Bag Corp., 251 F.

Supp. 184 (M.D. Tenn. 1966) .................... 92

Hicks v. Crown Zellerbach Corp.,

49 F.R.D. 184 (E.D. Pa. 1968) .................. 92

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express,

Inc., 417 F. 2d 1122 (5th Cir. 1969) ........... 92

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone

Co., 433 F. 2d 421 (8th Cir. 1970) ........... 37, 91

Paroli v. Bolton, 57 Misc.2d 952,

293 N.Y .S.2d 938 (Sup.Ct. Duch.

Co. 1968) ...................................... 48

Pennsylvania v. O'Neill, 348 F.Supp.

1084 (E.D. Pa. 1972) , aff'd in rel.

part by an equally divided court,

473 F .2d 1029 (3d Cir. 1973) (enbanc)................................. 39, 41, 46, 47

52, 73, 89

Pennsylvania v. Sebastian, dkt. no.

72-987, W.D. Pa., filed Dec. 4,

1972 ........................................... 37

Penn v. Stumpf, 308 F.Supp. 1238

(N.D. Cal. 1970) ......................... 37, 39, 91

Shield Club v. City of Cleveland,

dkt. no. C 72-1088, N.D. Ohio,

filed Dec. 21, 1972 ......... 39

United States v. Lathers, Local No.

46, 471 F . 2d 408 (2d Cir. 1973) ................ 73

United States Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission:

Dec. No. 72-0284 (Aug. 9, 1971), '

CCH, EEOC Decisions 116304 (1973) ............. 79

Dec. No. 71-1529 (Apr. 2, 1971),

CCH, EEOC Decisions 1(6231 (1973) ............. 79

Dec. No. 72-1497 (Mar. 30, 1972),

CCH, EEOC Decisions 1(6352 (1973) ............. 87

Dec. No. 72-1460 (Mar. 19, 1972)

CCH, EEOC Decisions 116341 (1973) ............. 87

Dec. No. 71-1418 (Mar. 17, 1971)

CCH, EEOC Decisions K6223 (1973) ............. 79

Western Addition Community Organization

v. Alioto, 330 F.Supp. 536 (N.D.

Cal. 1971) ................................. 37, 39

Other authorities

Administrative Code of the City of

New York, Chapter 19, Section 487a-3.0(b)...... g7

Civil Service Commission of the

City of New York, Rules and

Regulations, Rule IV, Section III-4.3.2(b)..... 87

G. Cooper & R. Sobol, Seniority and

Testing under Fair Employment Laws:

a General Approach to Objective

Criteria of Hiring and Promotion,

82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598, 1667-68 (1969)...... 49, 58

Note, The Collateral Consequences

of a Criminal Conviction, 23 Vand. L. Rev.

929 (1970)

Page

88

PagoPresident's Commission on Law Enforce

ment and Administration of Justice,

Task Force Report: Corrections, (1967)............ 88

R. L. Thorndike, Personnel Selection (1949).......... 58

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

Rule 23............................................ 91, 92

United States Department of Health,

Education & Welfare, 10-State Nutrition

Survey 1968-70..................................... 79

United States Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission,

Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures, 29C.F.R. §1607.1-14 (1972)............ 48, 51, 54

United States Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission,

National Origin Discrimination Guidelines,

29 C.F.R. §1606.1(b) (1972)........................ 79

I

i

:

I *

i

t

*

-vi-

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For the Second Circuit

Dkt. No. 73-2287

Vulcan Society of the New York

City Fire Department, Inc., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees-AppeHants

-against-

Civil Service Commission of the

City of New York, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants-Appellees

-against-

Nicholas M. Cianciotto, et al. ,

Intervenors-Defendants,

Appellants-Appellees

Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Southern District of New York

Brief of Plaintiffs as Appellees and Appellants

Preliminary Statement

Plaintiffs submit this brief as both appellees

and appellants. We answer briefs submitted by defendants,

who are the various agencies and individuals responsible

for the content and administration of entrance and promo

tional procedures of the New York City Fire Department ("the

NYCFD"); by intervenors, who are three individuals who took

and passed the most recent examination for firemen for the

NYCFD; by President Richard J. Vizzini of the Uniformed

Firefighters Association of Greater New York ("Vizzini"),

who appears as an amicus curiae; and by the Jewish Rights

Council ("the JRC"), which also appears as amicus curiae. And

we make our arguments for a partial reversal of the District

Court's order.

Defendants and intervenors have appealed from an

order of the United States District Court for the Southern

District of New York, entered on August 8, 1973, following

a 7-day hearing and a 38-page opinion of United States

District Court Judge Edward Weinfeld. Defendants and inter

venors challenge the order insofar as it (i) declared un

constitutional written civil service examination 0159

("examination 0159" or sometimes just "0159") given in 1971

to NYCFD firemen candidates, (ii) permanently enjoined the

use of the results of that examination in making appointments

of firemen, (iii) directed defendants to prepare a new ex

amination "in accordance with professionally accepted methods

of test preparation" rather than the method they had used

-2-

before, and (iv) provided for interim relief. Amicus Vizzini

urges that the District Court lacked jurisdiction and asks

for a reversal and dismissal; the JRC attacks the findings

of the District Court that the examination for entrance for

the NYCFD was unconstitutional and maintains that the in

terim relief was "itself unconstitutional".

We appeal from Judge Weinfeld's decision insofar

as he did not award us summary judgment and denied us a

hearing, as an alternative, on our contention that three

automatic grounds for disqualification of NYCFD firemen

candidates are unconstitutional: a height of less than 5'6";

a conviction for petit larceny or any felony; and failure to

have a high school or equivalency diploma. We also argue

that the District Court's interim relief, including its failure

to incorporate compensatory relief, was inadequate.

Issues Presented for Review

1. Was the District Court "clearly erroneous" in

finding that examination 0159 had a discriminatory impact

on blacks and Hispanics?

2. Was the District Court "clearly erroneous" in

finding that defendants did not sustain their heavy burden

of proof to show that 0159 fairly tested the candidates'

-3- I

relative qualifications to be firemen in the NYCFD?

3. Did the District Court err in rejecting plain

tiffs proposal for interim relief, which would have required

the appointment of qualified candidates to the NYCFD on a

kasis among minorities (black and Hispanics) and non

minorities?

4. Did the District Court err in not finding

that the minimum height requirement for candidates was an

unconstitutional feature of the entrance procedures of the

NYCFD on the record before it; and, if the record was in

complete on this issue, was it error for the District Court

to refuse plaintiffs a hearing on the issue?

5. Did the District Court err in not finding

that the requirement that candidates possess a high school

or equivalency diploma was an unconstitutional feature of

the entrance procedures of the NYCFD on the record before it;

and, if the record was incomplete on the issue, was it error

for the District Court to refuse to allow plaintiffs a

hearing on the issue?

6. Did the District Court err in not finding

that the automatic disqualification for certain criminal

convictions was an unconstitutional feature of the entrance

procedures of the NYCFD; and, if the record was incomplete

I

-4-

on the issue, was it error for the District Court to refuse

to allow plaintiffs a hearing on the issue?

Statement of the Case

Proceedings in the District Court

Plaintiffs filed a class-action complaint in this

case on January 11, 1973; the complaint (Doc. 1)* sought in

junctive relief to change civil service selection procedures

used for the appointment and promotion of firemen and officers

fin the NYCFD. Plaintiffs challenged the procedures on the

grounds that they have had and will continue to have a dis

criminatory impact on blacks and Hispanics ("minorities")

and cannot be justified since they do not fairly measure the

relative abilities of candidates for appointment and promotion.

*Citations to numbered documents in the record on appeal are

shown by the abbreviation "Doc." followed by the document's

number.

-5-

Plaintiffs include five black and Hispanic indivi

duals who took civil service entrance examination 0159 for

firemen administered on September 18, 1971, but either did

not receive a passing score or did not receive a passing

score that was high enough to make it likely that they would

be appointed firemen. Plaintiffs also include the Vulcan

and Hispanic Societies of the NYCFD, whose memberships

include most of the black and Hispanic firemen and officers

of the NYCFD. Defendants are all of the administrative

agencies of New York City and their heads who are responsible

for promulgating and administering the challenged selection

procedures.

When we filed the complaint, we also moved

by order to show cause for a preliminary injunction

(pendente lite) against appointments of firemen based on

the results of examination 0159 and against the establish

ment of any eligible list of candidates based on the results

of that examination.

Prior to the hearing we engaged in two skirmishes

with our opponents over requests for stays to try to stop the

-6-

appointment of some 120 firemen. We lost them both; and,

eventually, prior to the District Court's opinion,

302 fireman appointments were made from the 0159 eligible

list. Of this group of 302, only 8 were minorities.

Judge Weinfeld heard evidence at the preliminary

injunction hearing on three days in January and four in

early February, 1973. This hearing was concerned exclusively

with plaintiffs' claim that examination 0159 had a discrimina

tory impact on minorities and could not be shown to be job-

related. While some of the proof at the hearing was also

relevant to other issues in the complaint, plaintiffs did

not purport to put in their case on any other issue. For

example, plaintiffs did not offer any expert testimony

relating to the minimum height or high school diploma re

quirements for NYCFD firemen.

After the hearing was over and during argument

Judge Weinfeld suggested that he would like to know our

views concerning whether we would accept the 7-day hearing

on the preliminary injunction as a complete and final hearing

on all entrance requirement procedures (1043-50). In

^Numbers in parentheses refer to pages in the transcript of

proceedings on our motion for a preliminary injunction.

-7-

a letter dated February 12, 1973, we voiced our qualified

acceptance of that suggestion — proposing to leave for

future hearings the several issues on entrance procedures

on which there was little, if any, evidence offered (P.App. la).

On May 1st, Judge Weinfeld heard oral argument on the question.

Over our objection, he ruled that the hearing was closed

and his ruling would be final on all issues on entrance

procedures, although he would accept any written material

on these issues so long as he received them before he

ruled on the merits of plaintiffs' motion for preliminary

injunction (P.App. 11a—12a). We then duly put in affidavits

to support a motion for summary judgment on the issues of the

legality of the minimum height and education requirements

and the automatic disqualification because of petit larceny

or felony convictions (Doc. 27). Those affidavits went un

contradicted .

Judge Weinfeld handed down his 38-page opinion on

June 12, 1973 (8a-37a).** After an order and counter

order had been proposed intervenors successfully

^Citations to pages of our photostated appendix are made by

the abbreviation "P.App." followed by the page number.

**Numbers in parentheses followed by the letter a refer to

pages of the appendix filed by defendants and intervenors.

-8-

entered the case, on motion and without opposition, only

for the purposes of commenting on the proposed orders and

participating in any appeal. After several sessions with

counsel, Judge Weinfeld issued an order, entered on August

8, 1973, awarding interim relief and endorsed a memorandum

opinion that explained the basis for it (41a-44a).

Judge Weinfeld1s opinions

This Court will find that much of our oppo

nents' arguments are based on a misreading of Judge

Weinfeld's opinion-in-chief (8a-37a) and a total refusal

to read his memorandum opinion relating to interim

relief. What our opponents say is that Judge Weinfeld

found that only twenty questions were non-job related

and the rest of 0519 was fine; they concede he was

right as to those twenty questions, but wrong as to the

consequences.

We review the two opinions of Judge Weinfeld

briefly to prove our opponents' error.

In his 38-page opinion Judge Weinfeld found,

on uncontroverted evidence, that examination 0159 had

-9-

a substantial discriminatory impact on minorities (14a-

23a). Once that impact was found, Judge Weinfeld —

following the mandate of the case law — said the bur

den had shifted to the defendants and that they bear

"a heavy burden of justifying [their] contested ex

aminations by at least demonstrating that they were

job-related" (23a).

Next, Judge Weinfeld reviewed the three

generally accepted principles of psychological test

ing, after stating that satisfying those methods

appeared to be "precisely the correct response to a

prima facie showing of discriminatory impact" (25a).

He observed that defendants and their predecessors

had never used or attempted to use the two most

reliable ways to "validate" examinations and that

some courts have deemed this fatal (26a). But he

found it unnecessary to reach that issue because

defendants failed to justify the examination on the

single ground they claimed it could be (27a).

As Judge Weinfeld noted, defendants based

-10-

their justification solely on the ground that the ex

amination had "content validity." But for an examina

tion to be valid on the basis of its "content," the

first requisite required by professionals is a thorough

study of the job and the preparation of a "job analysis"

(29a-30a), "a thorough survey of the relative importance

of the various skills involved in the job in question

and the degree of competency required in regard to each

skill" (28a).

No job analysis was ever done by defendants

or their predecessors; and, indeed, Judge Weinfeld cata

logued exactly how amateurishly 0159 was prepared (28a-

29a). He concluded (29a):

"The record compels the conclusion that the

procedures employed by defendants to construct Exam

0159 did not measure up to professionally accepted

standards concerning content validity."

Judge Weinfeld then alluded to the cases that

take the view that without a careful job analysis there

could be no content validity. Again, however, he found

it unnecessary to go that far. And what he next said is a

clear holding in this case: that even if defendants did

not have to conform precisely to professional standards,

-11-

the manner in which they prepared the examination was so

unsatisfactory under the decisional law in this Circuit

that defendants had not met their burden of establishing

strong "probabilities" of job-relatedness. In a sentence,

he simply could not find that there was content validity

in this examination in view of the procedures followed by

defendants. Here are Judge Weinfeld's words in reliance on

this Court's decision in Chance v. Board of Examiners,

458 F. 2d 1167 (2d Cir. 1972) (30a-31a):

"Even if defendants were not required to conform pre

cisely to all the requirements of a professional job

analysis, it is clear that the methods actually em

ployed were below those found unsatisfactory in

Chance, where defendants made a much more extensive

inquiry into the nature of the job in question. In

deed, the most which Mr. McCann was willing to state

was that it was 'possible' to prepare a job-related

examination by the means Mr. Scheinkman described.

Defendants' burden, however, is not to establish pos

sibilities but to demonstrate strong probabilities."

Next, Judge Weinfeld met defendants' contention

that, regardless of the inadequacies of the means which

were employed, 0159 still could be valid as to content. He

then gave further grounds for his decision. He said that

the testimony of "defendants 1 expert *** not only failed to

meet *** [defendants'] burden but even acknowledged the pre

sence of a major flaw in the examination which is in itself

-12-

fatal" (31a). It was in this context that Judge Weinfeld

spoke at length about the conceded failure of 20% of the

examination, the 20 questions that dealt with New York

City government and current events. Still in this con

text, he went on to spell out another glaring failure:

the omission of a competitive physical test in view of the

substantially physical nature of a fireman's job (32a-33a).

Thus, a reading of Judge Weinfeld's opinion, be

fore his summary, establishes that, in view of the way the

examination was prepared, he cannot find that examination

0159 was job-related; but, even if he were to adopt the

argument of defendants, he would have to find against them

on the very face of the examination for two reasons: the

conceded erroneous 20 questions and the lack of a compe-

tive physical test. Judge Weinfeld's summary puts the

matter far beyond cavil (33a-34a):

"In view of the unprofessional manner in which the

written examination was prepared, the inclusion of

a section on current events and City government

which constitutes 20% of the examination without any

showing of its relation to the job of fireman and

the refusal to include a competitive physical ex

amination component despite the request of the

Commissioner or to provide a satisfactory explana

tion for its elimination, defendants have failed to

sustain their burden of demonstrating job-related-

ness; indeed, the evidence strongly indicates that

Exam 0159 was not sufficiently related to the job of

fireman to justify its use."

-13-

Whatever lingering doubts one could have —

based on wishful thinking imposed on Judge Weinfeld's em

phasis on the 20 questions and the lack of a competitive

physical — have to be set at rest by his memorandum op

inion on interim relief.

On the date for the settlement of an order, Judge

Weinfeld was presented with three competing proposals for

interim relief. Ours would have allowed appointments pen

dente lite by creating two lists, a list of minorities who

passed 0159, and a list of non-minorities who passed. We

asked that, for every one appointment from one list, there

should be an appointment of one from the other list. The

Corporation Counsel for defendants proposed a ratio of two-

to-one. Intervenors, on the other hand, urged what they

now suggest to this Court: they asked Judge Weinfeld

simply to eliminate the 20 questions on City government

and current events and regrade the tests and create a new

list; and they argued in their supporting affidavit to

Judge Weinfeld that all he did was to pass on the 20

questions. Judge Weinfeld adopted the two-list proposal,

but, sua sponte, with a ratio of three-to-one. In the

accompanying memorandum the trial court made it clear

that intervenors had misinterpreted its opinion. Judge

Weinfeld wrote (43a):

"The intervenors would keep the list intact so that

-14-

appointments would be made in the order of ran"k. This

they propose to accomplish by eliminating the twenty

questions, 20% of the total examination, which the

Court found impermissible and regrading the papers

•with appointments made thereafter according to order

of rank. However, this procedure eliminates from

consideration other factors relating to the written

examination, as well as the factor of competitive

rating of the physical examination, the lack of which

the Court also took into account in reaching its deter

mination . "

Of course, Judge Weinfeld's opinion did not ex

plore every avenue of proof over seven days of trial on a

record of over 1,000 pages; nor can we do it here. What

we feel this Court ought to have is a picture of how the

hearing progressed and some of the "compelling" facts, to

which Judge Weinfeld alluded, and which truly mandated a

finding that 0159 was bad in toto — no matter how much

leeway defendants would be allowed on the governing law.

The evidence at the hearing

Plaintiffs' case and cross-examination took most

of the time in the District Court. We put on four witnesses

who dealt principally with the nature and relative impor-

ance of various traits and abilities that make for good

firemen and the difficulties minorities had in taking and

passing examination 0159. We put on four other witnesses

to talk about statistic-gathering on examination 0159; the

defendants — ably represented in the District Court by the

Corporation Counsel's office — had full opportunity to

examine these witnesses. It was one of our witnesses who

-15-

gave the only detailed view in the record of the training

school and the picture of teaching methods used at the school.

We also called Edward Schenkman, an adverse witness

employed by defendant Department of Personnel. It was his

testimony that furnished the story of the manner in which

examination 0159 was prepared. We went further and called

Commissioner Robert O. Lowery of the NYCFD; and he testified

concerning the nature of a fireman's job, the urgent need of

the NYCFD to increase the number of minorities in its ranks

and how the achievement of this objective has been frustrated

by the disadvantage of minorities on written civil service

examinations such as 0159.

Plaintiffs also offered the testimony of two expert

witnesses. Professor Edward Option, an expert in the field

of psychological testing and assessment, gave evidence of

the professionally recognized standards for preparing and

validating employment examinations; he demonstrated the ob

vious, that these standards had been ignored on 0159 and

that, as a result, 0159 clearly lacked content validity.

Then Professor David Siegmund of Columbia University, an

expert in mathematical statistics, showed how the presently

available statistical evidence established the discrimina

tory impact on minorities of examination 0159. His testi

mony was uncontradicted.

-16-

In answer, defendants first called Chief John T.

O'Hagan of the NYCFD. He testified about the nature of a

fireman's job and stated, based on his knowledge of the job,

that he favored a competitive physical examination for fire

men. In contrast, Captain James Meyers, who had been located

somewhere out of the NYCFD and recommended as a witness by

defendants' examination expert (969), testified for defend

ants that a qualifying physical examination was sufficient.

The defense's chief witness was its examination ex

pert, Forbes McCann. No question: Mr. McCann has a personal

stake in the outcome of this and similar litigation since

a large part of his business consists of preparing and sel

ling civil service examinations (783-86).

Mr. McCann's testimony was confusing and at times

contradictory, perhaps because he had only an "extremely ...

short" time to review 0159 (926). He was very uncertain con

cerning the meaning (924-25) and content (1025-26) of the only

professionally recognized written standards on test valida

tion revealed by the record (Exh. 6). He first denied

(898-902) then later admitted (1024-25) that the results of

tests of verbal comprehension in written form can differ

significantly from those of tests given in oral form. He

seemed at a loss to explain whether the vocabulary words in

0159 should or should not have been taken from "firemanic"

materials (955-60).

-17-

Nearly all of Mr. McCann's testimony concerning

examination 0159 was based on the result of his one-day

"brief job analysis" of NYCFD firemen (830, 986). Mr.

McCann said that a thorough job analysis would have taken

him between three days and two weeks "depending on what

[he] found" (968-69). He also acknowledged that before

he even started his "job analysis" he had agreed to testify as

an expert witness for the defense in support of examination

0159 (966-68).

The bias inherent in Mr. McCann's litigation-con

scious methodology revealed itself in his testimony. His

list of the ten traits "necessary for success as a fireman"

(835-36) omits some traits which were identified as very

important by the NYCFD firemen and officers who testified, such

as the willingness to follow orders and the ability to func

tion under stress (13-14, 693, 707, 776-77). His highly

qualified description of the physical trait necessary —

"sufficient" strength for "moderate" periods (835-36) --

bears little resemblance to the description of a fireman's

job by NYCFD officials as highly physical in nature, but

correlates very well with some defendants' desire to retain

a qualifying physical examination. There can be little

wonder that Judge Weinfield found Mr. McCann's testimony

"totally unpersuasive" (33a).

Nonetheless, Mr. McCann in many respects gave

-18-

testimony favorable to plaintiffs. He acknowledged that he

"would not have used" examination 0159, "God forbid" he had

prepared it (1026-27), and that fully one-fifth of the ex

amination was not sufficiently job-related to have been in

cluded in his judgment (850).

One further observation: almost as damaging to de

fendants' cause as the testimony of their expert was their

failure to call the witnesses most vital to a claim of con

tent validity. Absent from the stand were:

Chief Hartnett, the only member of the NYCFD ap

parently contacted in connection with the preparation

of 0159 (88-89, 439-40);

the examiners in the Department of Personnel who

actually prepared the questions used in 0159 (97, 802-03);

Morris Brownstein, a retired employee of the De

partment of Personnel, who edited the questions included

in 0159 as the chief of the responsible examining di

vision (88, 98);

Herbert L. White, the current head of the examin

ing division responsible for firemen entrance examina

tions (86) ;

Chief Lewis J. Harris, the current supervisor of

the probationary fireman training school (432-33, 702-

03, 712, 976), whose non-appearance was especially sur

prising in view of defendants' claim that the purpose

of 0159 was to measure the areas of knowledge neces

sary to absorb the training given at the school (94-

96, 131, 135-36);

any instructor or former instructor at the pro

bationary fireman training school;

Chief Bernard Muller, the current head of the

NYCFD's Bureau of Personnel and administration, who

together with Chief Harris was identified by Chief

f*

!

i

i

-19-

O'Hagan as a man whom he would consult concerning the

manpower needs and requirements of the NYCFD (702-04);

any person in the Department of Personnel familiar

with the manner in which the fireman's examinations pre

vious to 0159 had been prepared; and

any statistical expert to deny or rebut the show

ing made by plaintiffs and their expert of the discrim

inatory impact of 0159.

The extent of this missing cast of characters sug

gests that it had to be the trial strategy of defendants to

provide Judge Weinfeld with as little information as possible

concerning the preparation of examination 0159 and the na

ture of the probationary fireman's training experience. Surely

that was the effect.

From the witnesses at trial and a welter of documen

tary material the facts emerged that could only lead to the

result that Judge Weinfeld reached. We now look at those

facts, citing not only to our own case but to the testimony

offered by defendants.

The Facts

The entry level civil service position in the

NYCFD is that of fireman. Under civil service regulations

a fireman candidate must first take a written entrance

examination formulated by the Department of Personnel and

administered approximately once every four years. The ex

aminations are graded, all candidates scoring below the

passing grade of 70 are eliminated from further consideration

-20-

and the remaining candidates are ranked in order of their

scores (18,587-89). The resulting "eligible list" remains

in force until the next entrance examination is administered

and a new eligible list established (627-29) .

As positions of firemen become available they are

filled by the candidates at the top of the current eligible

list, provided that these candidates survive a subsequent

qualifying stage of the selection procedure — including

a medical examination, a physical examination and a charac

ter review.

The discriminatory impact

On September 18, 1971, defendants administered

examination 0159 for firemen to a group of 14,168 candidates.

After a lengthy delay caused principally by a freeze on

fireman appointments imposed by the City's Mayor (457-61),

defendants established an eligible list on January 18, 1973,

ranking in the order of their scores on examination 0159

the 12,049 candidates who passed it (175-77). During the

job freeze, the top ranking 7,987 men had been called for

the qualifying physical and medical examinations; a total of

4,462 men appeared for and passed this process (177-93; Exhs.

8, 8A).

Throughout its entire history the NYCFD has been

-21-

predominantly white (410-11, 417-18). At present minorities

comprise less than 5% of the firemen and officers of the

NYCFD (457-58). In contrast, the percentage of minorities

among the male population of New York City between the ages

of 19 and 28 (the age group qualified to become firemen in

the NYCFD) is approximately 32% and may be even higher

(633-36; Exh. 23, pp. 34-108; Exh. 24, pp. 34-429).

Because plaintiff Vulcan Society had actively re

cruited minority applicants for 0159, we had statistics

available to present to Judge Weinfeld. Various members of

plaintiff Vulcan Society took a visual "headcount" at the

0159 examination sites of the number of minority candidates

who took examination 0159 (398-401, 403-04). These black

firemen stationed themselves at the doorways and, using

counting machines, clicked off all the recognizable blacks

and Hispanics; they were instructed to be, and were, conser

vative: when in doubt, they didn't click. Thus, if there

are errors in their count, it could only be in an under

counting (397, 401, 506-07, 612-13, 620). The headcount

showed that, at the least, 1,646 minorities took examination 0159.

On a percentage basis this was 11.5%. The evidence suggests

that many eligible minorities were deterred from taking the

examination by their fear of failing it (19) and by the

resentment in minority communities toward the predominantly

I

.

white NYCFD (429-31; Exh. 13, p. 3).

I

The NYCFD itself made racial categorizations of

the 4,462 candidates on the 0159 eligible list who appeared

for and passed the qualifying stage of the selection process

— the physical examination and medical examination (177-83,

425). Of those finally qualified candidates only 249 or

5.6% were minorities -- 223 blacks and 26 Hispanics (Exhs.

8 and 8A).

In view of the number of firemen appointments

planned and prior experience the only candidates with a real

chance of appointment were those in roughly the top ranked

pool of 2,418 candidates -- of which 2,310 (95.5%) were

white and 108 (4.5%) were minorities (423, 625-31, 539-41).

The decline in the percentage of minorities from the 11.5%

who took examination 0159 to the 4.5% in this pool of fin

ally qualified candidates (523-25; Exh. 19) is statistically

significant (571-73) to an overwhelming degree: as Profes

sor Sigmund testified, it would have occurred by chance less

than one time out of 10,000 (526-28). Thus the selection

procedure as a whole had a sytematic, clear and substantial

discriminatory impact on minorities (528-29, 539). For ex

ample, 18.4% of the whites who took the examination attained

a place in the top finally qualified pool of 2,418 candidates

but only 6.6% of the minority takers did so — a disparity

-23-

of almost 3 to 1 (529-31; Exh. 19).

There can be no serious argument against the pro

position that written examination 0159 itself -- not the later

qualifying tests — must have been responsible for the maior

portion, if not all, of the discriminatory impact of the

whole procedure; the opposite view is illogical and runs

against all reasonable probabilities (531-36, 541-47).

Moreover, there was powerful direct confirmatory

evidence of what the laws of probability dictated. First,

minorities appeared in greater numbers as you went down the

eligible list (595-99). Second, the NYCFD and the United

States Department of Labor conducted a special tutorial

program for certain minority persons planning to take ex

amination 0159 (420-21, 426; Exh. 13), yet they fared badly.

Even the 119 tutorial students who managed to pass examination

0159 (427-28, 549) tended to rank significantly lower on the

0159 eligible list than the candidate, population as a whole;

their performance on the examination was definitely inferior

(563-66, 556-62; Exhs. 20 and 21). Indeed, only 18 of the

119 passing tutorial students ranked in the first 4,000 of

the eligible list. This number is disproportionately low

as compared to the size of this passing group, and there is

less than once chance out of 1,000 that such a low number

could have been the result of chance (556-59).

-24-

The failure of justification

The fact that minorities were disadvantaged in

competing against non-minorities on 0159 hardly comes as a

surprise. Written civil service examinations such as 0159

and the similar previous NYCFD fireman exams (88-89, 423)

"are almost certain to have discriminatory impact" on min

orities (430-31; Exh. 13, p. 3). As both plaintiffs' and

the defendants' examination experts agreed, minorities and

blacks in particular score significantly lower than whites

on nearly all kinds of written examinations (240-43; 1041-42;

Exh. 13, p. 3). In particular they have been shown to score

significantly lower than whites on written tests supposedly

aimed at testing ability to learn, of which examination

0159 is claimed to be an example (1041-42).

Examination 0159 (Exh. 2) was a written multiple

choice examination consisting of five sections, each with

20 questions. Its purpose was to determine which applicants

had the capacity to learn and perform the functions of a

fireman and, within this qualified group, to rank the appli

cants in an order which predicted their relative likeli

hood of job success (792-93, 912-13; Exh. 4). As defendants'

expert told us, the examination is "valid" if it achieved

its "goal of predicting competence" (806, 886-87): that is,

if the test scores attained by applicants, and thus their

-25-

ranks on the 0159 eligible list, accurately predict the

relative quality of their job performance (192-93; Exh. 6,

pp. 12-13). If the test scores lack demonstrable and sub

stantial predictive significance for job performance the

examination is invalid and should not be used to select

firemen (194, 792-93).

The procedures used to prepare 0159 ensured —

as Judge Weinfeld found — that it could not achieve its goal.

These procedures did not meet the standards recognized by

professionals as necessary to prepare a valid examination

(209-12, 891, 1026-27); and they went far below them. As

the experts tell us, an examination intended to predict

training and job performance should be prepared with "the

greatest care" so that the skills, abilities and traits

measured by the test accurately reflect those necessary to

effective training and job performance (Exh. 6, p. 3; 794).

Examination 0159, to the contrary, was prepared in a most

casual manner and with minimal attention devoted to the

nature of a fireman's training and job (88-110, 126-40,

209-12, 297, 1026-27). Not even an attempt was made to per

form a thorough and systematic "job analysis" (99-104),

which is the basic starting point for the creation of a

valid examination (199, 202, 324-25; 989; Exh. 6, pp. 12-13;

Exh. 6, C3 and Comment, p. 15).

I

j

Examination 0159 was composed in this way: I

Edward Scheinkman, then assistent chief of the examining

division of the Department of Personnel of the City of New

York, gathered up the file on previous fireman examinations,

form notices of examination including the class specifica

tions, some firemen's magazines and unspecified material

from the NYCFD (88, 101-03, 135). Mr. Scheinkman believed,

wrongly (792-93, 912-13), that the sole purpose of 0159 was

to measure the areas of knowledge necessary to enter the

probationary firemen training school (94-96, 131, 135-36).

He had only a "general knowledge" concerning the content of

the training program; he did not know the relative use of

written materials, lectures and demonstrations in the pro

gram (129-31). He called upon the NYCFD's Chief of Personnel

who referred him to a Chief Hartnett, whom Mr. Scheinkman,

although no one else, remembers as having then been in

charge of the training division of the NYCFD (88; but see

441, 725-26). The purpose of that contact was to get an

opinion as to the areas of knowledge that should be included

in the written test (88).

Chief Hartnett thought that the areas that were

covered in the last test should be covered again and, in

addition, that there should be an area on city government

and current events. The Department of Personnel felt that

-27-

there was "no reason to dispute him" (89)• Thus the areas

of the last examination were covered in 0159 and in addition

some 20 questions in the area of city government and current

events were included (89).

The actual drafting of the questions was en

trusted by Mr. Scheinkman to more junior examiners of the

Department of Personnel (97). There is no indication that

any of these examiners possessed any knowledge (794, 1034-

35) about a fireman1s training or job, or that they had ever

prepared a previous examination for firemen (97-98).

Commissioner Robert Lowery of the NYCFD was not

consulted about the proposed content of examination 0159,

and he knows of no one else with the NYCFD who was con

sulted (439-40) . While he and various members of the NYCFD

were concerned about the impact that such examinations may

have on minorities (423; Exh. 13), no one in the Department

of Personnel appears to have considered whether the areas

or questions of 0159 were culturally biased or would have

a discriminatory impact on minorities (112-20, 122).

The only discussions Commissioner Lowery had

with the Department of Personnel relating to the 1971 selec

tion procedure concerned his unsuccessful attempt to have

a competitive physical examination reinstituted. Commissioner

-28-

Lowery and many senior officers of the NYCFD now believe

and believed in 1971 that the physical examination should

be competitive (439-41, 451-52, 704-06). He was told that

it was too expensive and time consuming to have a competi

tive physical examination (441-42). But competitive physical

examinations had been conducted over the years until they

were eliminated prior to the 1968 examination (440-41).

|

After the examiners prepared a draft of 0159

it was reviewed by their superiors, but not by Mr. Scheinkman

(98). Nor does it appear that this draft or the final pro

duct was shown to or discussed with Chief Hartnett or any

one else in the NYCFD (98, 430-40).

As a result of all this, not even defendants'

own expert witness, Forbes McCann, would have used the

examination produced by the Department of Personnel (1027).

He would have omitted entirely fully one-fifth of the ex

amination's questions — because he did not feel confident

that they were job-related (850). At one point he gave the

court a true reading of his feelings about the quality of

examination 0159 as a whole in this manner: "If I had

written such an examination, God forbid * * (1026).

Moreover, under professionally recognized

standards even a properly prepared examination is presumed

-29-

to be invalid unless and until its job-relatedness has been

verified by a proper "validation" study (235-37; Exh. 6,

p. 12, fourth para.). Defendants admitted (105-06, 206)

that they never subjected 0159 or its predecessors to any

of the three types of professionally recognized validation

processes: (i) predictive validation; (ii) concurrent

validation; and (iii) construct or "content" validation.

The most preferable method of demonstrating

validity is by a predictive validation study in which the

test scores of job applicants are compared with their later

job performance (193-95, 315, 814, 828-30). The second

best method is by a concurrent validation study in which

the examination is administered to present employees and

compared with either their past or future job performance

(193-96, 826).

Contrary to the arguments in this appeal, def

endants could have performed a predictive validation study

of one or more of the fireman examinations prior to 0159

to determine the appropriateness of the subject matter area

covered by these exams and 0159 (88-89, 817, 878-79). It

was also feasible for defendants to perform a concurrent

-30-

validation study of examination 0159 itself (193-96). All

that has been needed is initiative and competence. Indeed,

New York City recently let bids for a citerion-related

validation study in connection with examinations for police

man and two other positions (987-89).

As to the less preferable "content" validation

studies of 0159 or any of its similar predecessors, defend-

I

ants did not even attempt an explanation at the hearing for

their failure; their inaction is inexcusable in view of

the sturm and drang about validation of civil service ex

aminations in urban communities.

The evidence at the hearing actually established

that examination 0159 was not even in the ballpark of "con

tent validity. "

A fireman's job is principally a physical job, once

a man understands the nature of the position. Above-average

strength, ability, dexterity and stamina are essential (7,

13-14, 440-41, 452, 705-06, 766, 771-72). In addition to

physical ability, experienced officers regard as among the

most important traits needed to be an effective fireman

these: ability to understand and willingness to follow oral

orders (13, 776-77); ability to function as a member of a

team and get along with fellow firefighters (769, 774);

-31-

ability to function under stress while performing extremely

demanding physical work (13-14, 693, 707); and job interest

— a willingness to do the job (13, 690).

An adequate level of common sense intelligence is

also necessary (440, 690), but this common sense usually

is called for in the form of action in firefighting situa

tions , and not in any great measure in the form of reading

comprehension (40-44, 477-85, 668-75, 731-36, 740-44, 751-

58). A fireman must be able to "profit by experience" in

these situations (726).

A fireman does not need a large or sophisticated

vocabulary. Nor does he need much mathematical or scienti

fic aptitude — the few positions that require a measure of

such aptitudes, such as motor pump operator, are filled

solely by firemen who are selected and attend a special

training program (18, 71-72, 498-502, 776). Knowledge of

current events and the structure of city government is un

related to the work of a fireman (13-14, 690, 850).

The NYCFD is a "semi-military organization" (373,

972) and, as such, the emphasis of its training program is

on learning through the constant repetition of drills and

manual evolutions (29-31, 375-76, 395, 469-70, 914-15).

Only a small portion of the fireman's training curriculum

-32-

involves reading or writing (375-80, 489-90). Retesting

and drills apparently insure that no one who really wants

to be a fireman ever fails to graduate from the probationary

fireman training school (388-89).

After graduation from probationary school, the

emphasis is still on repeated drilling in manual evolutions,

both individually and as a company, supplemented by lectures

and question and answer sessions (368-71, 376-77, 498-99,

696-97, 768, 772-73). Written materials play a very small

role in a fireman's on-the-job training (687-89, 723, 779-

80) .

The content of 0159 bears scant relation to the

content of a fireman's job or training experience (219-30,

238-39, 281-82, 323-26). Among the more obvious incongrui

ties between the content of 0159 and the nature of a fire

man's job are these:

its section on city government and current

events, a full one-fifth of the examination, is

plainly and concededly not job-related (850; see

209-10, 293-94);

the "word meaning" section includes words

(such as "attest" and "destitute") which obviously

** play no part in a fireman's working vocabulary;

fully one-fifth of 0159 is taken up with

"mechanical, scientific and mathematical" ques

tions , thus measuring knowledge and skills which

play a very minor role in a fireman's learning

and job experience; and, perhaps most importantly,

-33-

the examination tests knowledge, skills and

traits only through a written medium, yet by far

the largest portion of a fireman's training, both

at the probationary school and on the job, takes

the form of oral communication, visual demonstra

tions and drilling.

Examination 0159, of course, wholly failed to

assess the candidates' relative possession of such import

ant traits as the willingness to follow orders and the

ability to function in physically taxing situations while

under stress.

As Judge Weinfeld noted, the lack of job related

ness of any series of questions in 0159 was exaggerated in

effect by the lack of a good spread among the scores. Missing

five questions could mean a difference of over a thousand

places on the eligible list (32a).

In sum, examination 0159 emphasizes some areas

wholly irrelevant to a firemanfe job and some having only

minimal significance, while taking no account of other skills

and traits at the heart of the job. On the record of this

case, Judge Weinfeld had no basis to find examination 0159

"job-related" -- with or without the concededly bad 20% on

City affairs and current events and even if the preparation

of the examination had been done in some tolerably profes

sional way.

-34-

Argument

POINT 1

The District Court's finding that exam

ination 0159 had a significant and

substantial discriminatory impact upon

minorities was not clearly erroneous.*

Plaintiffs' burden

Contrary to the apparent belief of the amici

(Vizzini's Brief pp. 4, 7 and JRC's Brief pp. 15, 19) it

was no part of plaintiffs' burden to show that defendants,

in establishing and administering 0159, acted with a con

scious intent to discriminate against minorities. Rather

than the usually fruitless search for motives, the test is

one of effect: Did 0159 exclude from appointment a signi

ficantly higher percentage of minority than non-minority

candidates and potential candidates? Chance v. Board of

Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167, 1175-76 (2d Cir. 1972), aff'g 330

F.Supp. 203 (S.D.N.Y. 1971) ("Chance"). Bridgeport Guardians,

Inc, v. Bridgeport Civil Service Comm'n, dkt. no. 73-1356,

slip opin. no. 894 at 4554-56 (2d Cir., June 28, 1973),

aff'g in rel. part, 354 F.Supp. 778 (D. Conn. 1973) ("Bridge

port" ). Once plaintiffs showed that impact, their prima

* Answering Intervenors' Brief, Point I (pp. 7-13), JRC' s

Brief, Point I (pp. 9-15); Vizzini's Brief,(pp. 4, 7J

-35-

facie case was made out and the "heavy burden" shifted to

defendants to show, at a minimum, that the discrimination

resulted from use of a true merit examination, one that

fairly measured the candidates' relative possession of the

skills and abilities necessary to perform the duties of a

fireman. Chance, 458 F.2d at 1176.

Apparently, defendants have been sufficiently

persuaded by Judge Weinfeld's thorough analysis of the evi

dence and their familiarity with the record and Chance and

Bridgeport not to challenge here (def. brief, p. 3) Judge

Weinf eld' s finding that "there can be no doubt" of the discrim

inatory impact of examination 0159 (22a). Intervenors do

challenge this finding, but their arguments cannot with

stand analysis.

The proven past discrimination

First, intervenors wholly ignore the facts that

the evidence established 0159 to be but the latest in a

long series of similar discriminatory civil service examin

ations which have resulted in the present gross underrep

resentation of minorities in the NYCFD in comparison with

their presence in the general population (88—89, 423, 430—

31; Exh. 13, p. 3). There is a startling disparity: 5%

-36-

of NYCFD are minorities; the City's general population of

minorities is over 30%.

As Judge Weinfeld noted, some courts have viewed

such disparities as self-sufficient prima facie proof of

discriminatory impact. See Pennsylvania v. Sebastian, dkt.

no. 72-987 (W.D. Pa., filed Dec. 4, 1972) (0% minorities

in police department versus 4.5% in population)*; Western

Addition Community Organization v. Alioto, 330 F.Supp. 536,

538-39 (N.D. Cal. 1971) ("Western Addition”) (.22% minorities

in fire department versus 14% in city's population); Penn

v. Stumpf, 308 F.Supp. 1238, 1243 n.7 (N.D. Cal. 1970) (2 to4%

Negroes in police department versus 32 to 45% in the

population; motion to dismiss complaint denied) ; cf_. Parham

v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 433 F.2d 421, 426 (8th

Cir. 1970) (Title VII litigation), and cases there cited.

Here, Judge Weinfeld, as have other courts, re

garded the population statistics as confirmatory of plain

tiffs' other evidence of discriminatory impact (Opin. 16a).

See Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315, 323 (8th Cir. 1971),

adopted in rel. part, 452 F.2d 327, 331 (8th Cir.) (en banc),

cert, denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972) ("Carter") (0% minorities

in fire department versus 6% in population); Bridgeport,

354 F.Supp. at 785 (3.6% minorities in police department

♦Document 28 in the record on appeal contains a copy of all

unreported opinions cited in this brief.

-37-

versus 25% in population); Fowler v. Schwarzwalder, 351 F.Supp.

721, 723 (D. Minn. 1972) ("Fowler") (1 to 2% minorities in fire

department versus 4 to 8% in the population).

We submit that the extreme population-fireman

disparity in this case is especially persuasive proof of

the discriminatory impact of the similar previous examina

tions when added to two other factors: (i) the admissions

of defendants attributing the disparity largely to these

examinations (417-30, 1041-42; Exh. 13, p. 3); and (ii)

the fact that the position of fireman is not one whose nature

suggests that few minorities possess the necessary job

skills and traits (16a). See Castro v. Beecher, 334 F.Supp.

930, 936, 939, 943 (D. Mass. 1971), aff'd in part and rev'd

in part, 459 F.2d 725, 732-33 (1st Cir. 1972) ("Castro");

of. Chance, 330 F.Supp. at 214 (declining use of population

statistics in context of supervisory educational positions).

Defendant Lowery, perhaps in the best position of

all the defendants to know, admitted that civil service

examinations such as 0159 have proven to be a significant

stumbling block for minorities seeking appointment as fire

men (417-30). Defendants' expert agreed with ours (240-43,

1041-42) that minorities almost invariably are disadvantaged

in competing on written tests which emphasize verbal ability.

-38-

See Castro, 334 F.Supp. at 943; Arrington v. Massachusetts

Bay Transportation Auth., 306 F.Supp. 1355, 1358 (D. Mass, i

1969) ("Arrington"); Bridgeport, 354 F.Supp. at 791-92.

|

The sharp impact of 0159

Second and more important, we have here direct

evidence of discriminatory impact: "hard statistical

data showing that [minorities] * * * fared demonstrably

worse than others" on the challenged examination. Castro,

459 F .2d at 731.

Examination 0159 was used to compile a competi

tively ranked eligible list of applicants; it was not ad

ministered on a simple pass-fail qualifying basis, as has

been true of nearly all the written civil service examina

tions challenged in prior litigation. Chance; Castro;

Shield Club v. City of Cleveland, dkt. no. C 72-1088 (N.D.

Ohio, filed Dec. 21, 1972) ("Shield Club"); Davis v .

Washington, 348 F.Supp. 15 (D.D.C. 1972) ("Davis"); Western

Addition; Pennsylvania v. O'Neill, 348 F.Supp. 1084 (E.D.

Pa. 1972) ("O'Neill"), aff'd in rel. part by an equally

divided court, 473 F.2d 1029 (3d Cir. 1973 (en banc);

Penn v. Stumpf, supra. Furthermore, only the highest

ranking candidates on the eligible list stand a real

chance of being reached for appointment before the list

expires.

-39-

It follows that, contrary to intervenors' asser

tion (brief , pp. 10-12), -the statistics most probative of

the discriminatory impact of 0159 are not pass/fail ratios,

such as were used in Chance, but rather the proportion of

minorities among the candidates who succeeded in placing

high enough on the eligible list to have a realistic chance

of appointment. Contrary to defendants' statement (brief,

pp. 15-16), in the few cases involving ranked eligible

lists, the courts have recognized this important distinction

between competitive and qualifying examinations. Bridgeport,

354 F.Supp. at 788 & n. 5, 792 & n. 8a; Fowler, 351 F.Supp. at 723;

Arrington, 306 F.Supp. at 1357-58.

The evidence established that of the group of

candidates on the 0159 eligible list with a realistic

chance of appointment — roughly the highest ranking finally

qualified group of 2,418 candidates — only 4.5% are minor

ities as distinguished from the 11.5% of minorities in the

total candidate population. Although 18.4% of the non

minorities who took the examination attained a place among

this group of top ranking candidates, only 6.6% of the

minority takers did so — a disparity of almost 3 to 1.

Judge Weinfeld was correct in holding (15a-17a)

-40-

that this severe disparity more than meets the test of "a

significant and substantial" discriminatory impact. Chance,

458 F.2d at 1175. It is almost identical to the quantum

of impact shown in Bridgeport. Bridgeport, 354 F.Supp. at

784-87 (minorities 11% of applicants but only 3.6% of police

force, and whites passed exam at a rate 3-1/2 times that

of minorities). It is noticably more severe than the im

pact shown in other cases, including Chance itself. Chance,

330 F.Supp. at 210-13 (average passage rate for minorities

was 31.4% versus 44.3% for whites and on seven examinations

minorities passed at a higher rate than whites); 0 1 Neill,

348 F.Supp. at 1089-90 (whites passed at a rate less than

twice that of minorities); Castro, 334 F.Supp. at 942 (whites

passed at a rate about 2-1/2 times that of blacks).

The reliability of plaintiffs'

statistics____________________

The statistics on which Judge Weinfeld's finding

of discriminatory impact is based are reliable both as

to the method used to collect them and their completeness;

his finding of reliability was hardly "clearly erroneous".

Intervenors seem to question the bona fides of

plaintiff Vulcan Society's headcount, the source of the 11.5%

minority 0159 participation statistic (Int. brief, p. 8).

-41-

But this headcount could not have been somehow rigged

to affect this litigation. Its results were reported to def

endants on September 20, 1971 (Exh. 12), long before this

litigation was contemplated and well prior to the NYCFD's

own 1972 ethnic study of the highest ranking group of candidates

(Exh. 8). Thus at the time the headcount was conducted and

its results reported the Vulcans could not have known what

i

statistics would aid a Chance type complaint.

Moreover, the headcounters were subject to rigorous

cross-examination at the hearing, and Judge Weinfeld had full

opportunity to assess their credibility and the reliability of

their count. Similar methods have been accepted in this kind

of litigation, and to deny the use of this type of evidence is

to place an insuperable obstacle to assertions of constitutional

rights. O'Neill, 348 F. Supp. at 1088-89.

Intervenors also attack another aspect of plain

tiffs' proof: the use of the NYCFD ethnic survey of the

highest ranking finally qualified group of candidates,

which established that only 4.5% of this group were minori

ties. Intervenors argue, as defendants did at length before

42-

Judge Weinfeld, that the observed sharp decline in the per

centage of minorities from the 11.5% in the entire candidate

population to the 4.5% in the finally qualified group should

be attributed to factors other than poor minority perform

ance on 0159. Like defendants below, intervenors offer

nothing besides implausible conjecture in support of this

thesis (brief, pp. 8-12).

Intervenors list eight possible ways a candidate

could have been barred from the finally qualified group

even though he had scored well on 0159 (brief, pp. 2, 9-10).

Of these, the latter five can be quickly dismissed for they

relate to automatic grounds of disqualification. It is

inconceivable that more than a miniscule number of candi

dates bothered to take examination 0159 when the notice of

examination (Exh. 4) clearly told them they would be dis

qualified automatically regardless of their test performance

because they did not have the minimum height, or had been

convicted of petty larceny, or lived in Connecticut, and

so on. The possibility that defendants' character investi

gation of candidates could have influenced the percentage

of minorities in the finally qualified group must also be

dismissed for defendants tell us that the NYCFD ethnic count

was performed prior to the character investigation (def.

brief, p. 2). Moreover, defendants' counsel informed the

-43-

Icourt that only four 0159 candidates had been disqualified

on grounds of character (P. App. 3a).

This leaves only the qualifying physical and

medical examinations as possible eliminators of high scor

ing minority candidates. There is no reason to presume

that black and Hispanic candidates failed either of these

examinations at rates much higher than non-minority candi

dates. Defendants possess the name and address of every

0159 candidate who did fail these tests. However, despite

every opportunity at the hearing to do so, they did not

even attempt to show that minorities were disproportionately

disqualified by these examinations. That they have or

could have performed such a study is clear from the record,

which contains a study relating to the 1968 examination

(Doc. 27, Exh. F).

Intervenors raise another "possibility": in a city

with a high unemployment rate among minorities they ask the

Court to believe that a large number of minority candidates

who performed well on 0159 simply "dropped out", choosing

not to appear for the later qualifying steps in the selec

tion procedure (brief, p. 10). The proposition is absurd

on its face. Again, defendants knew the name and address

of each dropout yet abstained from any attempt to demonstrate

-44-

that a disporportionate number were minorities.

Moreover, there is a statistical flaw that infects

this whole notion that the subsequent qualification factors,

and not the written examination, might account for the

whole discriminatory impact. Intervenors just cannot ignore

the consequences of the sharp 3 to 1 disparity in minority

versus non-minority survival. Our expert, Dr. Siegmund,

i

|proved that this 3 to 1 disparity could be said not to re

flect minority disadvantage on the written examination only

if it be assumed that minorities were eliminated during

the subsequent qualifying procedure at a rate 2.7 times

that of non-minorities (531-36). Such a 2.7 to 1 elimina

tion factor is scarcely conceivable as a matter of proba

bilities, and no evidence has been presented to support it.

The only admissible conclusion is Judge Weinfeld's (22a):

"Here ftiere can be no doubt, whatever the

relative impact of component parts, that

in end result there was a significant and

discriminatory impact upon minorities

attributable in considerable part to the

written examination."

This Court's Chance case was decided on the basis

of statistics which were less reliable and complete than

those that were before Judge Weinfeld. This Court in Chance

considered the job-relatedness of only the written examin

ation component of a selection procedure that also involved

I

-45

an oral examination and an assessment of training and ex

perience. All three components were weighted in determin

ing a candidate's final score on the entire procedure, and

the trial court had available only statistics based on these

cumulative final scores. Chance, 330 F.Supp. at 217, 223

n. 25. In the absence of any evidence that the oral test

or the training-experience component discriminated against

minorities, this Court and the District Court had no diffi

culty invalidating the written examination as discriminatory.

So here, there being no evidence that the qualifying stage

of the procedure eliminated a significant number of high

scoring minority candidates, the demonstrated impact of

the entire procedure must be attributed to its only other

component — examination 0159. See O'Neill, 348 F.Supp. at

1088-90, 1094; Chance, 458 F.2d at 1172.

Intervenors raise one final quibble to plaintiffs'

proof of discriminatory impact. They say that Professor

Siegmund's analysis of the first 4000 rank positions on the

eligible list is invalid since as many as several hundred

candidates ranking below 4000 received the same grade score

on the examination (brief, p. 12). But plaintiffs' proof

was not limited to sorn artificially restricted portion of

the eligible list. Professor Siegmund extended his analysis

of the eligible list down to position 7987,thus including

-46-

all candidates that defendants called for the qualifying

process (182-83). Professor Siegmund found the same clear

picture of discriminatory impact among the candidates ranked

below 4000 as he did for those ranked above 4000 (593-94).

Furthermore, his analysis of the entire group of candidates

established an unmistakable trend for the proportion of

minorities to increase the further down the eligible list

one progresses, although even in the 7,000 to 8,000 rank

minorities are clearly underrepresented in proportion to

their presence in the total candidate population (595-99;

Exh. 19).

All the evidence confirms and none rebuts the

fact that written exam 0159 discriminated against minorities.

The total failure of defendants even to attempt a rebuttal

of plaintiffs' evidence buttresses the standing of our proof.

Carter, 452 F.2d at 323; O'Neill, 348 F.Supp. at 1094

(failure of defendants to rebut plaintiffs' "imperfect

statistics" supports reliance on them).

It is true that statistical proof of this nature

concerning discriminatory impact depends on an assessment

of the probabilities that the demonstrated varying levels

of performance of minorities and non-minorities could not

have been the result of chance. But all fact-finding in

volves an assessment of probabilities, and the statistical

-47

probabilities demonstrated in this case were overwhelming

— never less than 100 to 1 and up to 10,000 to 1 (527-58 ,

599-600). See United States Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission, Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures

§1607.5(c)(1), 29 C.F.R. §1607.1-14 ("EEOC Guidelines"),

at §1607.5 (c) (1) (probability of occurrance by chance of more

than 20 to 1 is statistically significant); Chance, 330 F.Supp.

at 210-13; Bridgeport, 334 F.Supp. at 784. When the 0159

statistics are confirmed by the general population statistics,

it becomes frivolous to urge that Judge Weinfeld's finding that

0159 had a substantial discriminatory impact upon minorities

was "clearly erroneous." Bridgeport, slip opin. at 4558.*

*As to Vizzini's claim that the District Court had no jurisdic

tion because we did not exhaust the administrative remedy by

taking our complaints of discrimination to the Civil Service

Commission (brief, pp. 3-4): our complaint is not directed against

the accuracy of specific answers in an "answer key", and thus there

is no administrative review offered or required. Paroli v. Bolton,

57 Misc. 2d 952, 959, 293 N.Y.S. 2d 938, 945 (Sup. Ct. Duch. Co.

1968). This is a civil rights case under the 14th Amendment to

the United States Constitution and the Civil Rights Act and the

best and primary place for such a case is in the federal courts.

Chance; Castro; Bridgeport; etc.

-48-

I I

It was not clearly erroneous for the

District Court to find that defendants

failed to meet their heavy burden of

proving, at a minimum, that examination

0159 was job-related. *________________

All our opponents — save it appears Vizzini at

one point (brief, p. 4) -- concede that once a discriminatory

impact is shown the "heavy burden" shifted to defendants to

justify the impact by demonstrating, at a minimum, that 0159

has a demonstrable and substantial relation to job perform

ance: that it succeeds in ranking candidates in accordance

with their actual capacities to perform the job and not in

accordance with irrelevant factors such as test-taking

abilities. Chance, 458 F.2d at 1176; Bridgeport, slip opin.

at 4557; Castro, 459 F.2d at 732-33. Defendants had to

show, in short, that 0159 was "reasonably capable of measur

ing 'what it purports to measure'" and that it was so good

as to be given 100% weight in the weeding and ranking pro

cess. Chance, 330 F.Supp. at 216; Bridgeport, 354 F.Supp.

at 792; G. Cooper & R. Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under

Fair Employment Laws: A General Approach to Objective

Criteria of Hiring and Promotion, 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598,

* Answering Defendants' Brief, Points I and II (pp. 8-28)

and Intervenors' Brief, Point II (pp. 13-30); Vizzini's

Brief, (pp. 5-8); JRC Brief, Point One (pp. 9-16) .

I

t

*

-49-

1667-68 (1969).

Our opponents say, however, that defendants met

their burden at the hearing on 80% of the examination and

the District Court was wrong in finding that the entire

examination was "unconstitutitonal". In various ways, they

would make three points:

1. Judge Weinfeld was wrong in suggesting that

the unprofessional manner of making up 0159 was a ground

for ruling out 0159.

2. Judge Weinfeld only affirmatively found that

20 questions were bad and, as to the balance, he made no

finding at all; the consequence, they say, is that the re

lief ought to be merely a discarding of the 20 questions

and a regrading of the candidates based on the 80 questions

that are left.