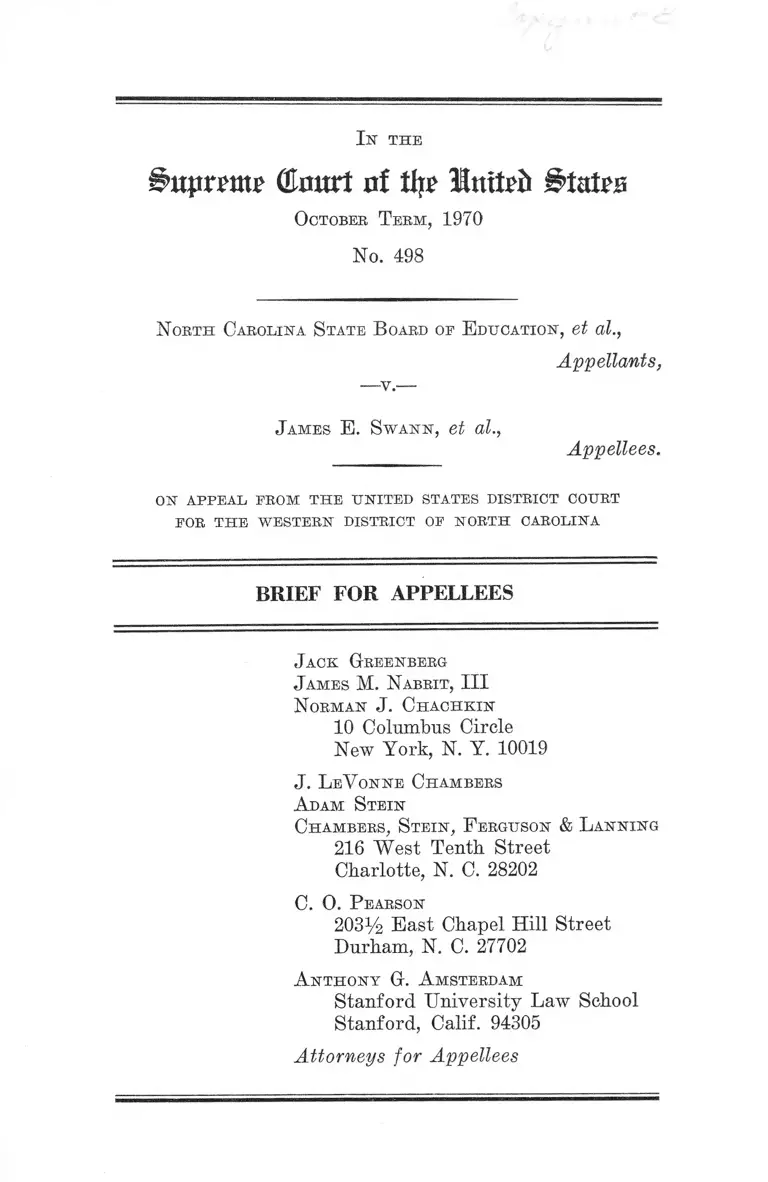

North Carolina State Board of Education v. Swann Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. North Carolina State Board of Education v. Swann Brief for Appellees, 1970. ad874dc0-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4026d61b-147d-4fde-9eb1-a0cb73c3fe82/north-carolina-state-board-of-education-v-swann-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

Isr th e

CCmtrt nf % States

O ctober T erm , 1970

No. 498

N orth Carolina. S tate B oard op E ducation , et al.,

Appellants,

J am es E . S w a n n , et al.,

Appellees.

o n a p p e a l p r o m t h e u n it e d s t a t e s d is t r ic t c o u r t

POR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OP NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

J ack G reenberg

J ames M. N abrit , III

N orman J . C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

J . L eV onne C hambers

A dam S tein

C ham bers , S te in , F erguson & F an n in g

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, N. C. 28202

C. O. P earson

2031/2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, N. C. 27702

A n t h o n y G. A msterdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, Calif. 94305

Attorneys for Appellees

Opinions Below

Jurisdiction .....

I N D E X

PAGE

1

1

Questions Presented .......................................................... 2

Statement ........ ............................-........................................ 3

Introduction ........ 3

Proceedings during 1969-70 before a Single Dis

trict Judge .................................................................. 4

Obstruction of the District Court Orders; Conven

ing of Three-Judge Court .... 7

Some Facts on Student Transportation ................. 12

Summary of Argument.............................................. 17

A rgu m en t

I. The Court Below Correctly Held that a

Portion of 1ST.C. Gen. Stat. §115-176.1, Known

as the Anti-Busing Law Is Unconstitutional

and in Violation of the Equal Protection

Clause and the Supremacy Clause of the Con

stitution of the United States ....................... 20

A. Introduction— The Provisions of the

Statute .......................................................... 20

B. The statute unconstitutionally interferes

with the school board’s affirmative duty

to dismantle the dual system..................... 26

11

C. The Appellants’ Argument Supporting

the Statute Rests on a rejected view that

there is no affirmative duty to desegre

gate the schools .......................................... 30

D. Additionally §115-176.1 is unconstitu

tional because it violates the principles

stated in Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S.

385 (1969) and also the doctrine of

Reitmcm v. Mulkey, 387 TJ.S. 369 (1967). 33

E. The Court Below correctly Concluded

that §115-176.1 also violates the Suprem

acy Clause of Article V I of the Consti

PAGE

tution ......................................................... 36

II. The Appellants Other Objections to the

Judgment Below Are Also Insubstantial .... 40

A. The motions to dismiss were properly

denied ............. 40

B. The District Court was empowered to

stay State Court proceedings to protect

or effectuate its judgments ......................... 41

C. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 does not

support appellants’ argument ..................... 42

III. The Court Has No Jurisdiction of the Appeal

Under the Doctrine of Bailey v. Patterson,

369 U.S. 31 .................................... 42

Conclusion 44

B rief A ppendix A —

Notification and Request for Designation of Three-

Judge Court with attached Exhibits D, E, F, and G

(filed February 20, 1970) ............................................. la

Exhibit A —

Opinion and Order of December 1, 1969

[omitted in printing, see Appendix in No. 281,

p. 698a] .................................................................. 5a

Exhibit B—

Opinion and Order of February 5, 1970

[omitted in printing, see Appendix in No. 281,

p. 819a] .................................................................. 5a

Exhibit C—

Order dated December 2, 1969 [omitted in

printing, see Appendix in No. 281, p. 717a] .... 5a

Exhibit D—

Complaint, Amended Complaint and two

Orders of Superior Court in Harris v.

S elf ...................................................... 6a, 14a, 19a, 21a

Exhibit E—

Statement by Governor Scott ............................. 23a

Exhibit F—

Letter by Governor S cott................................... 26a

Exhibit G—

Statement by Dr. Craig Phillips....................... 27a

B rief A ppendix B—

Opinion and Order of Three-Judge District Court in

Alabama, v. United States, et al., S.D. Ala., No.

5935-70-P, June 26, 1970 ................................................ 29a

Order of Dismissal.............................................................. 39a

I l l

PAGE

IV

Table of Cases:

Alabama v. United States, ------ F. Supp. ------ (S.D.

Ala. Civ. No. 5935-70-P, June 26, 1970) ......... 30, 39, 43

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396

U.S. 19 (1969) .................................................................. 43

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U.S. 31 (1962) ...........2,11,19,43

Bivins v. Bibb County Board of Education (M.D. Ga.,

No. 1926, May 22, 1970) ........ ;....................................... 39

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E.D. S.C. 1955) .... 30

Brooks v. Beto, 366 F.2d 1 (5th Cir. 1966, en banc),

cert, denied, 386 U.S. 975 (1957) .........................18, 32, 33

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

2, 26, 28, 30, 35, 36,41

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) ....26, 29

Brown v. South Carolina State Board of Education,

296 F. Supp. 199 (D. S.C. 1968), judgment affirmed,

393 U.S. 222 (1968) ........................................................ 37

Bryant v. State Board of Assessment, 293 F. Supp.

1379 (E.D. N.C. 1968) .................................................... 41

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 187 F. Supp. 42

(E.D. La. 1960), stay denied, 364 U.S. 803, judgment

affirmed, Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 365

U.S. 569 (1961) ............. .......................... .............. 19,36,42

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 188 F. Supp. 916

(E.D. La. 1960), stay denied, sub nom. Louisiana v.

United States, 364 U.S. 500 (1960), judgment af

firmed,, 365 U.S. 569 (1961) .................................. 18, 36, 38

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 190 F. Supp. 861

(E.D. La. 1960), judgment affirmed, New Orleans

v. Bush, 366 U.S. 212 (1961) .................. ..................... 36

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 191 F. Supp. 871

(E.D. La. 1961), judgment affirmed sub nom. Legis

lature of Louisiana v. United States, 367 U.S. 907

(1961) ............................................................................... 36

PAGE

V

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 194 F, Supp. 182

(E.D. La. 1961), judgment affirmed sub nom. Tug-

well v. Bush, 367 U.S. 907 (1961) .......................... ....... 36

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396 TJ.S.

290 (1970) ..................................................................... 44

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ........................ ..... 36, 41

Denny v. Bush, 367 TJ.S. 908 (1961) ....... .... ............. . 36

Dowell v. Board of Education of the Oklahoma City

Public Schools, 396 TJ.S. 269 (1969) ........................... 43

Dowell v. Board of Education of the Oklahoma City

Public Schools, 244 F. Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965),

affirmed, 375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir. 1967), cert, denied,

387 U.S. 931 (1967) ........................................................ 32

Ex parte Poresky, 290 TJ.S. 30 (1933) __ _______ _____ 43

Faubus v. United States, 254 F.2d 797 (8th Cir. 1958),

cert, denied, 358 U.S. 829 ...... .......... .................... ........ 40

Godwin v. Johnston County Board of Education, 301

F. Supp. 339 (E.D. N.C. 1969) ........................ ....... . 40

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968) ____________ 2,18,19,26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 43

Gremillion v. United States, 368 U.S. 11 (1961) ........... 36

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F. Supp.

649 (E.D. La. 1961), judgment affirmed, 368 U.S. 515

(1961) ............................................................................ . 37

Harris v. S e lf ............................................................. 3, 7, 25, 41

Harvest v. Board of Public Instruction of Manatee

County, 312 F. Supp. 269 (M.D. Fla. 1970) ____ ____ 40

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) ...........2,18, 33, 34

PAGE

In the Matter of Peterson, 253 U.S. 300 (1920) 41

VI

Katzenbaeh v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966) ................... 42

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, Colo., 313 F. Supp.

61 (D. Colo. 1970) ..... ....... .......................... ....... ..... . 35

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, M.D. Ala.

Civ. No. 604-E, March 12, 1970, March 16, 1970,

March 23, 1970 ................................................................ 39

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 267 F. Supp.

458 (M.D. Ala. 1967), affirmed sub nom. Wallace v.

United States, 389 U.S. 215 (1967) ......... ................. 36,40

Lee v. Nyquist, ------ F. Supp.-------- (W.D. N.Y. Civil

1970-9, Oct. 1, 1970) ................. ....................... ......18,33,35

Louisiana Education Commission for Needy Children

v. U.S. District Court, 390 U.S. 939 (1968) ________ 37

Marbury v. Madison (US) 1 Cranch 137 (1803) ........... 40

Meredith v. Fair, 328 F.2d 586 (5th Cir. 1962) ........... 40, 42

Mitchell v. Donovan, 398 U.S. 427 (1970) ............ .......... 11

Moore v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

312 F. Supp. 503 (W.D. N.C. 1970) ......... ................ ...1,11

Moore v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

No. 444, O.T. 1970 ____________ _________________ _ 4

Poindexter v. Louisiana Financial Assistance Commis

sion, 275 F. Supp. 833 (E.D. La, 1967), judgment

affirmed 389 U.S. 571 (1968) ................. ....................... 37

Poindexter v. Louisiana Financial Assistance Commis

sion, 296 F. Supp. 686 (E.D. La. 1968), judgment

affirmed, sub nom. Louisiana Education Commission

for Needy Children v. Poindexter, 393 U.S. 17 (1968) 37

Railway Mail Association v. Corsi, 326 U.S. 88 (1945) 31

PAGE

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) ........... 2,18, 33, 35

Rockefeller v. Catholic Medical Center, 397 U.S. 820

(1970)................................................................................. 11

V l l

PAGE

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969) ................... 42

Sparrow v. Gill, 304 F. Supp. 86 (W.D. N.C. 1969) ..... 13

Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U.S. 378 (1932) ................ . 40

Swann v. Charlotte-Meeklenburg Board of Education,

No. 281, O.T. 1970 ........................................ ................. 3, 4

Swann v. Charlotte- Mecklenburg Board of Education,

243 F. Supp. 667 (W.D. N.C. 1965), affirmed, 369

F.2d 29 (4th Cir. 1966); 300 F. Supp. 1358 (1969);

300 F. Supp. 1381 (1969); 306 F. Supp. 1291 (1969);

306 F. Supp. 1299 (1969) ; 306 F. Supp. 1301 (1969);

306 F. Supp. 1306 (1969); 311 F. Supp. 265 (1970) 5

Swann v. Charlotte-Meeklenburg Board of Education,

312 F. Supp. 503 (W.D. N.C. 1970) .......................... 1

Swift & Co. v. Wickman, 382 U.S. I l l (1965) .............. 19, 43

Thomason v. Cooper, 254 F.2d 808 (8th Cir. 1958) ...... 42

Turner v. Memphis, 369 U.S. 350 (1962) ................... 43

United States v. Board of Public Instruction of Polk

County, 395 F.2d 66 (5th Cir. 1968) ................ ..... 32

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), aff’d en banc, 380 F.2d

385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied, sub nom. Caddo

Parish School Board v. United States, 389 U.S. 840

(1967) .......................... - ........... .................................. ...31, 32

United States v. Montgomery County Board of Educa

tion, 395 U.S. 225 (1969) .......................... ...... .....18,31,32

United States v. Peters (US) 5 Cranch 115 (1809) ....18,38

United States v. Wallace, 222 F. Supp. 485 (M.D. Ala.

1963) ........................ ................... ........ ....................... . 40

Walker v. County School Board of Brunswick County,

413 F.2d 53 (4th Cir. 1969) ....................................... . 30

Wanner v. County School Board of Arlington County,

357 F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1966) ...................................... 18, 32

V l l l

Youngblood v. Board of Pubic Instruction of Bay

PAGE

County, Fla., ------ F.2d ------ (5th Cir., No. 29369,

July 24, 1970) ..................... ........... .............................. - 32

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. §1253 ................................ ........ .................... 1,19, 43

28 U.S.C. §2281 ............ ............................. ............ ..... 6,11,12

28 U.S.C. §2283 ............. ...... ...........................................-19, 42

28 U.S.C. §2284 ................................ ................................ . 6

New York Education Law, Section 3201(2) (McKinney

1970) .......................... .............. ...... ................... ....... ..... 33

N.C. Gen. Stat. §115-176.1 .................. 3, 8,11,17, 20, 22, 25,

26, 27, 29, 30, 33, 34,

35, 36, 38, 43, 44

Other Authorities:

1A Moore’s Federal Practice ............. ...... ............ ......... 42

NEA, National Commission on Safety Education,

1968-1969 Statistics on Pupil Transportation, 1970 .... 12

I n th e

i>ti|tr£OTr (Emtrt of the Bttitpfi Stairs

O ctober T erm , 1970

No. 498

N orth C arolina S tate B oard of E ducation , et al.,

Appellants,

—v.-

J am es E . S w a n n , et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

Opinions Below

The opinion of the three-judge district court is reported

as Swann v. Charlotte-Meclclenburg Board of Education

(also Moore v. Charlotte-MecMenburg Board of Educa

tion), 312 F. Supp. 503 (W.D. N.C. 1970).

Jurisdiction

Appellees submit that the Court does not have jurisdic

tion of a direct appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1253 because

the ease is not a “ civil action, suit or proceeding required

by any Act of Congress to be heard and determined bv a

district court of three judges” (emphasis added). Appel

lees’ argument in support of the contention that a three-

judge court was not required appears infra in Argument

III.

2

Questions Presented

1. Whether the judgment of the court below that a part

of the North Carolina anti-busing law is unconstitutional

should be affirmed:

(a) on the ground that it violates the equal protection

clause by interfering with school boards’ affirmative duty

under Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954),

and Green v. County School Board of New Kent County.

391 U.S. 430 (1968), to eliminate dual school systems;

(b) on the ground that it effects a racial classification

which violates the principles stated in Hunter v. Erickson.

393 U.S. 385 (1969), and in Reitman v. Midkey, 387 U.S.

369 (1967);

(c) on the ground that it violates the Supremacy Clause

by seeking to overturn the desegregation decisions of the

federal courts and in particular the decisions of the fed

eral district court in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg case.

2. Whether the court below properly (a) denied motions

to dismiss various defendants and (b) restrained parties

from seeking to enforce the anti-busing law by state court

injunction proceedings.

3. Whether the appeal should be dismissed on the ground

that no direct appeal is permitted inasmuch as the statute

involved was so clearly unconstitutional that no three-

judge court was required under the doctrine of Bailey v.

Patterson, 369 U.S. 31 (1962).

3

Statement

Introduction

This case is here on direct appeal to review a judgment

of a three-judge district court which held that a portion

of N.C. Gen. Stat. §115-176.1, known as the anti-bussing

law, was unconstitutional because it interfered with the

affirmative duty of local school boards under the Four

teenth Amendment to desegregate racially segregated

public schools and also violated the Supremacy Clause of

Article VI. The court enjoined all parties “ from enforc

ing, or seeking the enforcement of” the unconstitutional

portion of the statute. The proceeding in the three-judge

court was an ancillary proceeding connected with the school

desegregation case involving Charlotte-Meeklenburg which

is also now pending here as Swann v. Charlotte-Mechlen-

burg Board of Education, O.T. 1970, No. 281, certiorari

granted June 29, 1970.

This appeal was taken by the North Carolina State

Board of Education and four state officials.1 The Charlotte-

Meeklenburg Board of Education also filed a notice of

appeal from the same order, but has not filed a jurisdic

tional statement or docketed its own appeal. Instead, the

local school board has filed a motion in this Court to join

in the appeal of the state board of education, pursuant to

this Court’s Rule 46. 1

1 Appellants herein include the State Superintendent of Public

Instruction, the Governor of North Carolina, the Controller of the

State Board of Education, and a judge of the Superior Court of

Mecklenburg County who issued an order allegedly interfering with

the federal court desegregation orders. No notice of appeal was

filed on behalf of the .additional parties defendant Tom B. Harris,

et al., the plaintiffs in the state court proceeding of Harris v. Self;

nor was notice of appeal filed on behalf of James C. Carson, al

though the state argues in its brief that it is prosecuting the appeal

on his behalf (Brief of the Attorney General of North Carolina,

pp. 10-12. As to the notice of appeal, however, see A. 107-108.)

4

Another appeal from the same judgment is also pending

here as No. 444, O.T. 1970, sub nom. Moore v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education. The Moore case was

consolidated for hearing with the instant case in the three-

judge district court. It began as a suit in a state court

by parents seeking to enjoin the Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education from carrying out the desegregation

orders issued by the federal district court in Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, No. 281, O.T.

1970, cert, granted June 29, 1970. The Negro plaintiffs in

the Swann case were not named as parties in the Moore

case; only the school board is named as a defendant below

and an appellee in this Court. The school board removed

the Moore case to the United States District Court, but

both below and here has agreed with and supported the

argument of the plaintiffs-appellants Moore, et al. that

the North Carolina anti-bussing law is valid. The Negro

plaintiffs Swann, et al. moved in the district court for an

order adding the plaintiffs in the Moore case as parties-

defendants and enjoining them from interfering with the

district court’s desegregation orders. The order issued be

low, as noted above, enjoins all parties in both cases,

including Moore, et al., from enforcing or seeking enforce

ment of the unconstitutional portion of the anti-bussing

statute.

Proceedings during 1969-70 before a Single District Judge

The school desegregation case brought by Negro pupils

and parents against the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education was commenced in 1965 and there has been ex

tensive litigation ever since which has culminated in the

Swann case now pending in this Court. A full statement

of the history of the proceedings from 1965 to date is

contained in Petitioners’ Brief in Swann, No. 281, O.T.

0

1970.2 The ease has resulted in numerous reported deci

sions which are cited in the note below.3

On April 23, 1969, after a plenary hearing, the district

judge rendered a decision and order finding that the school

system was still unlawfully segregated and directing

that defendants file a plan for complete desegregation of

the system {Swann, supra, 300 F. Supp. 1358; App. No.

281, p. 285a-323a). The court specifically directed that the

school board consider altering attendance areas, pairing or

consolidation of schools, transportation or bussing of stu

dents and any other method which would effectuate a

racially unitary system (App. No. 281, p. 315a-316a). Exten

sive litigation ensued as the board submitted a series of

proposals and the court rejected them as unsatisfactory to

disestablish the segregated system (App. No. 281, pp. 448a-

458a; 579a-592a, 698a-716a, 819a-839a). In the midst of this

litigation about the remedy to implement the April 23 deci

sion, the North Carolina legislature enacted the anti-bussing

bill proposed by a member of the Mecklenburg delegation

(A.63-93). The measure which was ratified July 2, 1969,

included the following two sentences (later held unconsti

tutional) :

No student shall be assigned or compelled to attend

any school on account of race, creed, color or national

2 The parties in this case, No. 498, have stipulated that the record

and printed appendix in No. 281, O.T. 1970 and No. 349, O.T. 1970

constitute and shall be used as a part of the record in this case.

This is consistent with the view of the case taken by the court below.

Citations to the Appendix in Nos. 281 and 444 are indicated. The

appendix in this case is cited as “A. •—

3 See, e.g., Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

243 F. Supp. 667 (W.D. N.C. 1965), affirmed, 369 F.2d 29 (4th

Cir. 1966) ; 300 F. Supp. 1358 (1969) ; 300 F. Supp. 1381 (1969);

306 F. Supp. 1291 (1969); 306 F. Supp. 1299 (1969) ; 306 F. Supp.

1301 (1969); 306 F. Supp. 1306 (1969); 311 F. Supp. 265 (1970).

6

origin, or for the purpose of creating a balance or

ratio of race, religion or national origin. Involuntary

bussing of students in contravention of this Article is

prohibited, and public funds shall not be used for any

such bussing (A.91).

Plaintiffs in the Swann case promptly obtained leave to

file a supplemental complaint which sought injunctive and

declaratory relief against the above-quoted portion of the

anti-bussing law; they asked that a three-judge court be

convened pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§2281 and 2284 (App.

No. 281, pp. 460a-479a). However, no three-judge court

was convened at that time and the court took no action

on the requests for relief because the school board thought

that the anti-bussing law did not interfere with the school

board’s proposed plan to bus about 4,000 black children

to white suburban schools (306 F. Supp. at 1295; App. No.

281, p. 585a).

After further hearings to consider the board’s further

proposals during the fall of 1969 and the operation of the

interim, plan (which involved bussing black children to

formerly white schools), the district court finally directed

that a plan be prepared by the court’s expert consultant

(App. No. 281, p. 698a-717a). The court consultant’s plan

was ordered into effect in an order entered February 5,

1970, reported at 311 F. Supp. 265 (App. No. 281, 819a-

839a). The February 5 order provides for the alteration of

some school attendance areas, the creation of certain “ satel

lite” or non-contiguous zones from which pupils would be

transported to school, the pairing and clustering of certain

schools with the alteration of grade structures, and trans

portation for pupils who live more than walking distance

(as determined by the board) from the school to which

they are assigned. The pairing and clustering of 10 black

7

and 24 white elementary schools will result in pupils of

both races being transported to schools wdiich were for

merly segregated. The district court made extensive sup

plemental findings about the amount of transportation re

quired and its relation to the large school bus transportation

system which was already in operation in the community

(App. No. 281, p. 1198a-1220a).

Obstruction of the District Court Orders; Convening of

Three-Judge Court

Following the order of February 5, 1970, numerous citi

zens, under the banner of “Concerned Parents Association,”

held meetings to protest the order, vowing to defy, delay,

obstruct and in any way prevent its implementation. On

January 30, 1970, they filed a proceeding in the Mecklen

burg County Superior Court (Harris v. Self) and obtained

an ex parte temporary restraining order, purportedly pre

venting the superintendent from paying the fees and ex

penses of the court consultant as directed on December 2,

1969. (Appendix A, infra 6a). They filed an amended com

plaint on February 12, 1970, in the Mecklenburg County

Superior Court and obtained an amended temporary re

straining order which enjoined the Charlotte-Mecklen-

burg Board of Education from expending any money for

the purpose of purchasing or renting any motor vehicle

or operating or maintaining such for the purpose of in

voluntarily transporting students in the Charlotte-Mecklen-

burg school system from one school to another and from

one district to another (Appendix A, infra 19a). The order

entered by the Mecklenburg Superior Court on January 30,

1970, was modified to permit payment of the court con

sultant on approval of the Board of Education (Appendix

A, infra, 21a).

On February 11, 1970, Governor Robert W. Scott issued

a public statement to the effect that North Carolina General

8

Statute §115-176.1 prohibited the involuntary bussing of

students, that he had taken an oath to uphold the laws of

the State of North Carolina, and that he was directing all

officials to enforce this statute (Appendix A, infra 23a).

On February 12, 1970, Governor Scott instructed the Di

rector of the Department of Administration that “use of

public funds for providing bus transportation shall be

strictly in accordance with the appropriations made by the

1969 General Assembly, and for no other purpose. No

authorization will be given for use of any other funds

to provide bussing to achieve school attendance for the

purpose of creating a balance or ratio, religion or national

origins” (sic.) (Appendix A, infra 26a). Copies of the

letter were forwarded to Dr. A. Craig Phillips, the Super

intendent of Public Instruction; Dr. Dallas Herring, Chair

man of the State Board of Education; Mr. A. C. Davis,

the Controller of the State Board of Education; and Mr.

Tom White, Chairman of the State Advisory Budget Com

mission. Shortly thereafter, Dr. A. Craig Phillips issued

a similar statement and further advised that he was op

posed to bussing (Appendix A, infra 27a). On February

23, 1970, he wrote to Dr. William S. Self, Superintendent

of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools and advised, “ No

additional State funds will be allocated to the Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education to provide bussing of

students for the purpose of creating a balance or ratio of

students in the schools.” On the same date, Mr. A. C.

Davis directed a memorandum to the superintendent of

each local school system in the State advising that the

General Assembly had appropriated funds for the opera

tion of 9,510 buses during the 1969-70 school year and 9,635

buses during the 1970-71 school year. The memorandum

advised that approximately 9,443 buses were presently in

use and that, “ The appropriation does not include funds

for the transportation of thousands of additional students

9

and the operating costs of hundreds of additional buses

which might be made necessary by the reorganization of

schools. No additional State funds will be allocated to

school administrative units to provide bussing of students

for the purpose of creating a balance or ratio of students

in schools.”

On February 13, 1970, plaintiffs moved the court (A.

46-50; App. No. 281, p. 840a) to add as additional parties-

defendant the Governor of the State; Mr. A. C. Davis,

Controller of the State Board of Education; the Honorable

William K. McLean, the Superior Court Judge who issued

the temporary restraining order; each plaintiff in the

Superior Court proceeding and their attorney. Plaintiffs

also asked the court to add as additional parties-defendant

the Honorable James Carson who initially proposed the

statute here in question and who had made several public

statements of his intention to file a proceeding in the state

court to enjoin the school board from complying with the

February 5, 1970, order of the court. Plaintiffs further

sought to enjoin the enforcement of the state court restrain

ing order as modified on February 12, 1970, and to enjoin

the defendants from further interference with the imple

mentation of the orders of the district court.

On February 20, 1970, the resident district judge entered

an order reciting the various events and requesting that

the Chief Judge of the Circuit designate a three-judge

district court (A. 19-22; App. No. 281, p. 845a). A three-

judge court was designated on February 24, 1970, and addi

tional parties were added by order of February 25, 1970

(A. 17-18; App. No. 281, p. 901a).

Meanwhile, on Sunday night, February 22, 1970, approxi

mately 50 adults on behalf of themselves and their children

filed another proceeding (Moore v. Charlotte-MecUenburg

Board of Education) in the Mecklenburg County Superior

1 0

Court seeking to restrain desegregation of the Charlotte-

Mecklenburg schools as directed by the district court. At

10:16 p.m. on that Sunday night, the Honorable Frank

Snepp issued an ex parte temporary restraining order

enjoining the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education

and its Superintendent

from instituting or implementing or putting into oper

ation or effect, or expending any public funds upon,

any plan or program under which children in the City

of Charlotte or Mecklenburg County are denied access

to any Charlotte-Mecklenburg public school because of

their race or color or are compelled to attend any

prescribed Charlotte-Mecklenburg public school be

cause of their race or color. (App. No. 444, p. 19-20).

On Thursday, February 26, 1970, the board removed the

Moore case to the United States District Court (App. No.

444, p. 21-22). At a special meeting of the board on Fri

day, February 27, 1970, the board chose to comply with

the order of the state court rather than the orders of the

federal district court. The Superintendent announced that

all planning and activities then underway for implementa

tion of the district court’s order of February 5, 1970, were

terminated (App. No. 444, p. 31 or App. No. 281, p. 925a).

On the same date, plaintiffs moved the court to add the

plaintiffs in the Moore case, their lawyers and the Honor

able Frank Snepp as additional parties-defendant in this

case. Plaintiffs further sought an order enjoining the en

forcement of the state court order and enjoining any fur

ther efforts by all of the defendants from taking steps

which would prevent or inhibit the implementation of the

orders of the district court. Plaintiffs also sought an order

finding all members of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education and its Superintendent in contempt and im

posing a fine or imprisonment for each day that the defen-

1 1

Judge McMillan on March 6, 1970, entered an order

decreeing that the order by Superior Court Judge Snepp

in the Moore case “is hereby suspended and held in abey

ance and of no force and effect pending the final deter

mination by a three-judge court or by the Supreme Court

of the issues which will be presented to the three-judge

court on March 24, 1970” (App. No. 281, pp. 925a-927a).4

The three-judge court court eventually ruled in an opinion

dated April 28, 1970, that the challenged portions of the

anti-bussing law were unconstitutional in violation of the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and

the Supremacy Clause of Article VI of the Constitution

(312 F. Supp. 503, 510; A. 2; App. No. 281, p. 1305a). The

initial opinion denied injunctive relief and granted only

a declaratory judgment. However, this portion of the

original opinion was withdrawn5 and the court enjoined

all of the parties in the Swann and Moore cases from

“ enforcing, or seeking the enforcement of” the unconsti

tutional portion of N.C. Gen. Stat. 115-176.1.

Although plaintiffs Swann, et al. originally sought a

three-judge court, they subsequently urged upon the dis

trict court that it was empowered to act on the matter as

a single judge and that a three-judge court was not re

quired by 28 U.S.C. §2281 because of the doctrine of Bailey * 6

* Both the attorney general and the state court plaintiffs made

repeated efforts to disqualify or recuse Judge McMillan from sitting

on the three-judge panel. See App. No. 281, p. 1, docket entries

Nos. 143, 146, 148, 149, 154. On March 9, 1970, Chief Judge

Haynsworth of the Fourth Circuit denied the motions to disqualify.

Docket entry 155.

6 The three-judge court determined to grant an injunction rather

than merely a declaratory judgment after taking note of this

Court’s decisions in Rockefeller v. Catholic Medical Center, 397

U.S. 820 (1970), and Mitchell v. Donovan, 398 U.S. 427 (1970).

dants failed to comply with the court’s orders. (App. No.

281, p. 814a-917a).

1 2

v. Patterson, 369 U.S. 31 (1962). The three-judge court

rejected these arguments that a three-judge court was not

required.6 (312 F. Supp. 503, 507.)

Some Facts on Student Transportation

Student transportation has become an important, and

indeed, an essential auxiliary service in today’s education.

Nationally, over 18 million students were transported daily

to public schools during the 1969-70 school year. This rep

resented approximately 40% of the total public school en

rollment. NEA, National Commission on Safety Educa

tion, 1968-69 Statistics on Pupil Transportation, 1970.

Approximately 55% or 610,760 students in North Caro

lina were transported during the past school year. Trans

portation was offered to all public school pupils who lived

more than one and one half miles from the school to which

they were assigned and who: (a) resided outside of the city

limits; (b) resided outside the city limits as it existed

prior to 1957; (c) resided within the city limits but who

were assigned to a school outside the city limits or out

side of the city limits as it existed prior to 1957; and (d)

resided outside the city limits and were assigned to a

school within the city limits. While local school units

initially purchased school buses, operating costs and re

placements of the buses were paid by the state.

Pursuant to state statutes, the North Carolina State

Board of Education adopted rules and regulations to gov

ern transportation of students. (Plaintiffs Exh. 71 for 6

6 The court below said that it rejected “plaintiffs’ attack upon

our jurisdiction” (312 F. Supp. at 507). However, plaintiffs, by

a brief filed in the trial court sought to make clear that their argu

ment that a single judge might properly have disposed of the case

was not a denial that the three-judge district court had jurisdiction

over the matter, but rather that three judges were not required to

decide the ease under 28 U.S.C. §2281.

13

March 1970 hearing in original record). The State Super

intendent of Public Instruction had to approve any addi

tions to the bus fleet or replacements of old buses by local

units. Local units were also permitted to contract trans

portation of students who qualify under state law with

private transportation companies in lieu of purchasing and

operating school buses.

On August 13, 1969, a three-judge court in Sparrow v.

Gill, 304 F. Supp. 86 (W.D. N.C. 1969) held that the state

statute which authorized transportation of city students

who live in areas annexed by a city subsequent to 1957 dis

criminated against other city students who were denied

transportation. The State Board then amended its regu

lations to authorize transportation of all public school

children who live more than one and one-half miles from

their school whether or not they reside within the city

limits. This regulation has substantially increased the

number of students transported in North Carolina.

Even prior to the Sparrow decision, the State Board of

Education and State Superintendent made efforts to secure

transportation for all students who resided more than one

and one half miles from their school. Similar recommen

dations had been made by a study commission appointed

by the Governor in 1968 (App. in No. 281, 1202a; Plaintiff’s

Ex. 13 at March 1970 hearing in original record).

The district court quoted the relevant state-wide data on

transportation of students in its Supplemental Findings of

March 21, 1970:

“ The average school bus transported 66 students each

day during the 1968-69 school year; made 1.57 trips

per day, 12.0 miles in length (one w ay); transported

48.5 students per bus trip, including, students who

were transported from elementary to high school.

14

“During the 1968-69 school year:

610,760 pupils were transported to public schools by

the State

54.9 percent of the total public school average daily

attendance was transported

70.9 percent were elementary students

29.1 percent were high school students

3.5 students were loaded (average) each mile of bus

travel

The total cost of school transportation was $14,293,-

272.80, including replacement of buses: The average

cost, including the replacement of buses,, was $1,541.05

per bus for the school year— 181 days; $8.51 per bus

per day; $23.40 per student for the school year; $.1292

per student per day; and $.2243 per bus mile of oper

ation. (Emphasis added.)” (App. in No. 281, p. 1199a)

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education trans

ported approximately 23,600 students during the 1969-70

school year. An additional 5,000 students rode the public

transportation system at reduced fares. To transport the

23,600 students the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Edu-

cation operated 280 buses; made an average of 1.8 trips

per day per bus and carried an average of 83.2 students

per bus daily. Each bus averaged 40.8 miles round trip

per day and each trip took approximately one hour and

15 minutes one way.

The board also transported more than 700 kindergarten

children, ages 4 and 5, from 7 to 30 miles one way each day.

(Br. A16, A24.)7

7 The district court opinion of August 3, 1970, reprinted as the

Appendix to Petitioner’s Brief in No. 281, is cited as “Br. A. ■—

15

Transportation costs in tlie Charlotte Mecklenburg sys

tem have been relatively inexpensive, less than 1% of the

annual operating budget. The average cost for transporta

tion per pupil was $20.00 per year or 22 cents per day. As

indicated above, this closely approximates the average per

pupil cost on the state level.

Finding this extensive transportation and its relative

economy, the district court saw no reason why transporta

tion could not equally be afforded to students in order to

desegregate the school system (App. in No. 281, 1198a-

1209a; Br. A10-A26). The court noted that transporta

tion had been extensively used in order to maintain and

to perpetuate segregated schools (1200a). Through the

1964-65 school year, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education maintained racially overlapping attendance

zones in order to transport black students to black schools

and white students to white schools (App. No. 281, p.

1011a). Even during the 1969-70 school year when over

lapping bus routes had ostensibly been eliminated the school

board had continued to arrange transportation in order to

perpetuate segregated schools. Black schools had been

conveniently located near black residential areas as walk-in

schools. White schools had been located in outlying white

areas necessitating transportation of students. Thus, of

the 23,600 students transported during the 1969-70 school

year, only 541 of these students were transported to black

schools (App. No. 281, 1014a-1032a; 1203a- 1204a).

The district court further noted that in addition to

transportation, school district zones had been controlled

in order to preserve segregated schools. The court stated

in its order of June 20, 1969:

This issue was passed over in the previous opinion

upon the belief which the court still entertains that

the defendants, as a part of an overall desegregation

16

plan, will eliminate or correct all school zones which

were created or exist to enclose black or white groups

of pupils or whose population is controlled for pur

poses of segregation. However, it may be timely to

observe and the court finds as a fact that no zones

have apparently been created or maintained for the

purpose of promoting desegregation; that the whole

plan of “building schools where the pupils are” with

out further control promotes segregation; and that

certain schools, for example Billingsville, Second Ward,

Bruns Avenue and Amay James, obviously serve school

zones which were either created or which have been

controlled so as to surround pockets of black students

and that the result of these' actions is discriminatory.

These are not named as an exclusive list of such situa

tions, but as illustrations of a long standing policy of

control over the makeup of school population which

scarcely fits any true “neighborhood school” philos

ophy (App. No. 281, 455a-456a).

See also Reply Brief of Petitioners and Cross Respondents,

in Nos. 281 and 349, pp. 3-17.

The court found that transportation of students would

be necessary in order to desegregate the schools under

any plan that might be directed:

“Both Dr. Finger and the school board staff appeared

to have agreed, and the court finds as a fact, that

for the present at least, there is no way to desegre

gate the all black schools in Northwest Charlotte with

out providing (or continuing to provide) bus or other

transportation for thousands of children. All plans

and all variations of plans considered for this pur

pose led in one fashion or another to that conclusion”

(1208a).

17

The court stated in its Memorandum Decision of August

3, 1970 that although additional transportation would be

required under the plan directed by the court, comparable

transportation would be required under the other plans,

with the exception of the plan submitted by the board (Br.

A23). The court found, however, that the board had the

facilities and personnel to implement the plan directed

without any additional capital outlay during the first

school year.

No capital outlay will be needed to operate buses for

the 1970-71 school year. The state is ready and willing

to lend the few buses the board may need; replace

ments can be bought after actual need has been de

termined under operating conditions (Br. A23).

As the court had previously noted, the only thing neces

sary for the board to implement the plan directed was the

willingness of the members of the board to discharge their

constitutional responsibilities to the black children in the

school system (App. No. 281, 1219a-1220a),

Summary of Argument

I.

A portion of N.C. Gen. Stats. §115-176.1 was properly

held to be in violation of the Equal Protection and Su

premacy Clauses of the Constitution.

The act limits a school board’s powers to effectuate de

segregation of the schools in a manner which conflicts with

the board’s affirmative duty to eliminate a dual school

system as declared in Green v. County School Board of

The plan proposed by the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education would require transportation of an additional

5,000 students.

18

New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968). School boards have

an affirmative duty to bring about unitary systems and

to that end they may use a variety of techniques of de

segregation. Remedial measures for desegregation may

not be limited by an artificial concept of color-blindness

which functions to enable racial discrimination to continue.

United States v. Montgomery County Board of Education,

395 U.S. 225 (1969); Wanner v. County School Board of

Arlington County, 357 F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1966); cf. with

respect to jury discrimination Judge Brown’s opinion in

Brooks v. Beto, 366 F.2d 1 (5th Cir. 1966, en banc).

The act violates the principles of Hunter v. Erickson,

393 U.S. 385 (1969), and Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369

(1967), in that it effects an expressly racial classification

which makes it more difficult for black citizens to achieve

school integration, and its purpose and effect as re

vealed by its entire context is to encourage the main

tenance of segregation. New York’s similar law was inval

idated on these grounds. Lee v. Nyquist, —- F. Supp. •—-

(W.D. N.Y., Civil-1970-9, Oct. 1, 1970) (three-judge court).

The court below also correctly concluded that the Act

violates the Supremacy Clause by attempting to nullify

federal court desegregation mandates. Bush v. Orleans

Parish School Board, 188 F. Supp. 916 (E.D. La. 1960)

(three-judge court), stay denied, Louisiana v. United

States, 364 U.S. 500 (1960), affirmed, 365 U.S. 569 (1961);

United States v. Peters (US) 5 Cranch 115, 136 (1809).

II.

The various state officials were properly named as addi

tional defendants because the record shows that they in

fact took actions which threatened to interfere with Judge

McMillan’s court ordered desegregation plan in the Char-

lotte-Meeklenburg school case.

19

The district court was empowered by 28 U.S.C. §2283

to stay state court proceedings to protect or effectuate its

own judgments. Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 187

F. Supp. 42 (E.D. La. 1960) (three-judge court), affirmed,

365 U.8. 569; Thomason v. Cooper, 254 F.2d 808 (8th. Cir.

1958); Meredith v. Fair, 328 F.2d 586 (5th Cir. 1962), (en

banc).

The court below properly rejected appellants’ arguments

based on the Civil Rights Act of 1964 because that Act does

not limit the powers of the courts to remedy unconstitu

tional racial segregation in the schools.

III.

The direct appeal should be dismissed because the three-

judge court was not required by any Act of Congress.

28 U.S.C. §1253. Swift & Co. v. Wickham, 382 U.S. 111

(1965). The challenged portions of the anti-bussing act

presented no substantial question and were plainly un

constitutional under this Court’s Green decision, supra. No

three-judge court was required under Bailey v. Patterson,

369 U.S. 31, 33 (1962). Implementation of the requirement

that dual systems be dismantled at once is delayed by un

necessarily convening three-judge courts to rule on segre

gation laws.

2 0

ARGUMENT

I.

The Court Below Correctly Held That a Portion of

N.C. Gen. Stat. § 115-176.1, Known as the Anti-Busing

Law Is Unconstitutional and in Violation of the Equal

Protection Clause and the Supremacy Clause of the

Constitution of the United States.

A. Introduction— The Provisions of the Statute.

The North Carolina anti-busing law, N.C. Gen. Stat.

§115-176.1 (Supp. 1969), was ratified and became effective

July 2, 1969.8 It was entitled “An Act to protect the neigh

s NORTH CAROLINA

GENERAL ASSEMBLY

1969 SESSION

RATIFIED BILL

C h a p t e r 1274

H ouse B il l 990

A n A ct to protect t h e neighborhood school system and to

PROHIBIT THE INVOLUNTARY BUSSING OF PUPILS OUTSIDE THE DIS

TRICT IN WHICH THEY RESIDE.

The General Assembly of North Carolina do enact:

Section 1. There is hereby created a new Section of Chapter 115

of the General Statutes to be codified as G.S. 115-176.1 and to read

as follows:

“ G.S. 115-176.1. Assignment of pupils based on race, creed, color

or national origin prohibited. No person shall be refused admission

into or be excluded from any public school in this State on account

of race, creed, color or national origin. No school attendance dis

trict or zone shall be drawn for the purpose of segregating persons

of various races, creeds, colors or national origins from the com

munity.

Where .administrative units have divided the geographic area

into attendance districts or zones, pupils shall be assigned to schools

within such attendance districts; provided, however, that the board

of education of an administrative unit may assign any pupil to

a school outside of such attendance district or zone in order that

such pupil may attend a school of a specialized kind including but

not limited to a vocational school or school operated for, or oper-

2 1

borhood school system and to prohibit the involuntary

bussing of pupils outside the district in which they reside.”

Our supplemental complaint challenged the validity of only

the last two sentences9 in the second paragraph of the sec

ating programs for, pupils mentally or physically handicapped, or

for any other reason which the board of education in its sole dis

cretion deems sufficient. No student shall be assigned or compelled

to attend any school on account of race, creed, color or national

origin, or for the purpose of creating a balance or ratio of race,

religion or national origins. Involuntary bussing of students in

contravention of this Article is prohibited, and public funds shall

not be used for any such bussing.

The provisions of this Article shall not apply to a temporary

assignment due to the unsuitability of a school for its intended

purpose nor to any assignment or transfer necessitated by over

crowded conditions or other circumstances which, in the sole discre

tion of the School Board, require assignment or reassignment.

The provisions of this Article shall not apply to an application

for the assignment or re-assignment by the parent, guardian or

person standing in loco parentis of any pupil or to any assignment

made pursuant to a choice made by any pupil who is eligible to

make such choice pursuant to the provisions of a freedom of choice

plan voluntarily adopted by the board of education of an admin

istrative unit.”

Sec. 2. All laws and clauses of laws in conflict with this Act

are hereby repealed.

Sec. 3. If part of the Act is held to be in violation of the Con

stitution of the United States or North Carolina, such part shall be

severed and the remainder shall remain in full force and effect.

See. 4. This Act shall be in full force and effect upon its

ratification.

House Bill 990

In the General Assembly read three times and ratified, this the

2nd day of July, 1969.

H. P. T a ylo r , J r .

H. P. Taylor, Jr.

President of the Senate.

P h il ip P . G odw in

Philip P. Godwin

Speaker of the House of Representatives.

House Bill 990

9 Supplemental Complaint, para. I (A. 23-24).

2 2

tion, and it is only these two sentences—quoted hereafter—

which the three-judge court restrained and declared in vio

lation of the Equal Protection and Supremacy Clauses:

No student shall be assigned or compelled to attend

any school on account of race, creed, color or national

origin, or for the purpose of creating a balance or

ratio of race, religion or national origin. Involuntary

bussing of students in contravention of this Article

is prohibited, and public funds shall not be used for

any such bussing.

The first paragraph of §115-176.1 prohibits the exclu

sion of persons from public schools on account of race, and

prohibits the drawing of attendance districts for the pur

pose of segregating persons “ of various races, creeds, col

ors or national origins from the community.” The first

sentence of paragraph two permits (but does not require)

school authorities to assign pupils to schools by attendance

zones and states that boards may assign pupils outside

their zones to attend specialized schools “ or for any other

reasons which the board of education in its sole discretion

deems sufficient.” The next sentence—as quoted above—

forbids the assignment of students “on account of race,”

etc. or “ for the purpose of creating a balance or ratio of

race, religion or national origins.” This is followed by the

ban on “ involuntary bussing of students in contravention

of” the act, and the use of public funds to support such

bussing. The third paragraph excepts from the act tempo

rary assignments due to the unsuitability of a school, or as

signments necessitated by overcrowding of schools or—in

broad terms—“ other circumstances which, in the sole discre

tion of the School Board, require assignment or reassign

ment.” The fourth paragraph permits assignments on the

basis of parental or pupil request pursuant to a “ freedom

23

of choice plan voluntarily adopted by the board of educa

tion.”

As the opinion below states, both counsel for the appellees

Swann, et al. and the Attorney General of North Carolina

construed the statute in much the same way (A. 7-8). As

decribed by Judge Craven:

The North Carolina Attorney General argues that

the statute was passed to preserve the neighborhood

school concept. Under his interpretation, the statute

prohibits assignment and bussing inconsistent with the

neighborhood school concept. Thus, to disestablish a

dual system the district court could, consistent with

the statute, only order the board to geographically

zone the attendance areas so that, as nearly as pos

sible, each student would be assigned to the school

nearest his home regardless of his race. . . . [II] e recog

nizes of course, that the statute also permits freedom

of choice if a school board voluntarily adopts such a

plan. Thus the plaintiffs and the Attorney General

read the statute in much the same w ay: that it limits

lawful methods of accomplishing desegregation to

nongerrymandered geographic zoning and freedom of

choice. (A. 8.)

Appellees believe that the act’s prohibition against as

signments compelling a student to attend a school “ for the

purpose of creating a balance or ratio of race . . .” forbids

the use of a variety of desegregation techniques such as

redesigning zones so as to promote desegregation, pairing

schools or altering grade structures for the same end,

closing or consolidating schools to aid integration, or con

trolling school sizes by new construction, expansions, or the

use of portable classrooms, or location of school sites to

affirmatively promote integrated school systems. The anti

bussing sentence forbids the. use of existing transportation

facilities to promote desegregation or the initiation or ex-

24

pansion of bus services for that end unless pupils volunteer

to ride such “desegregation buses.” The effect of the pro

vision is to disable the board from changing assignment

patterns of any objecting pupils who previously resided

within walking distance (1% miles) of their schools for

the purpose of desegregating the school system.

The available materials indicating the legislative history10 11

of the anti-bussing law confirms this understanding of the

legislation.11 The bill’s sponsor, Mr. Carson, an attorney,12

said the purpose of the bill was stated in its title: “ to pro

tect the neighborhood school system and to prohibit the

involuntary busing of pupils outside the district in which

they reside” (A. 67). He said that “ involuntary” busing

10 Copies of the bill as originally introduced in the North Caro

lina House of Representatives, and the amendments made in a house

committee substitute and by the state senate are explained in the

deposition of the bill’s sponsor, State Rep. James H. Carson, Jr.

who represents Mecklenburg County in the legislature (A. 64-88;

various amendments and versions of the act appear at A. 89-93).

11 The original proposal by Rep. Carson on May 7, 1969 (A. 69,

74), designated House Bill DRH 255, provided that no pupils be

assigned outside their districts of residence except upon parental

application; that pupils be assigned to the closest school to their

homes in multi-school districts; that boards may provide transpor

tation for pupils assigned within or without their districts in the

boards’ “discretion,” but that pupils might not be bused outside

their districts to a more distant school except by their parents’

choice. The bill made no mention of race or color at all. The bill as

passed by the House and sent to the Senate (H.B. 990) appears at

A. 90-91. This version was a committee substitute more nearly

approximating the finally enacted bill. The committee substitute

contained the language held invalid by the court below—the second

and third sentences in present paragraph two. The Senate amend

ments added (in addition to grammatical changes) the proviso

about assigning pupils outside their zones to specialized schools

(first sentence of paragraph two) and the reference to freedom of

choice plans (end of paragraph four).

12 Mr. Carson was added as a defendant in this case not because

of his legislative role but because he threatened to file proceedings

in state court to prevent implementation of the court-ordered deseg

regation plan (A. 47, 53).

25

refers to the decision of pupils and parents (A. 80); that

the bill would prevent implementation of the Finger Plan

ordered by Judge McMillan which required clustering and

pairing of thirty-four elementary schools and the trans

portation of pupils (A. 85-86). The fact that the bill was

intended by its sponsor to conflict with Judge McMillan’s

April 23, 1969, order in the Swann case is confirmed by the

testimony of Mr. Carson:

Q. Look down, the report shows a question asked

you by Rep. Arthur H. Jones of Mecklenburg regard

ing any possible conflict between the bill and the de

cision of the Court should that become law. Would the

quotation there coming from you be correct? A. Not

completely, no. There could be a conflict or there could

not be, depending on what the Local Board decided

to do.

Q. Do you recall whether you said: “Well, of course,

I see a conflict. If there were no conflict I don’t think

there would be any need for the bill.”

Mr. Waggoner : Objection.

A. I don’t recall whether I said it or not. I don’t deny

it, I just don’t recall it.

Q. You might have said it? A. Yes.

The state court judges who applied §115-176.1 in the two

cases brought suit against the Charlotte-Mecklenburg

School board (Judge McLean in Harris v. Self, supra, and

Judge Snepp in Moore v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of

Ed., supra) issued temporary injunctions applying the

law to prevent implementation of the court-ordered Finger

desegregation plan. The Harris v. Self order (infra 19a)

enjoins the board from spending any funds “ for the pur

pose of involuntarily transporting students in the Charlotte-

Mecklenburg School System from one school to another and

from one district to another district.” Thus the order

26

broadly purports to block any reorganization of the sys

tem to desegregate the schools which involves “ involuntary

bussing.” The order makes no distinctions based on the

distances involved, age of the pupils or any such factors.

The Moore case order (issued ex parte on a Sunday night)

broadly enjoins “any plan or program under which any

children . . . are denied access to any Charlotte-Meeklen-

burg public school because of their race or color or are

compelled to attend any prescribed . . . school because of

their race or color.” (App. in No. 444, pp. 20-21.)

The school board upon being served with the Moore

injunction, promptly determined without any inquiry of

Judge McMillan to obey the state court order and directed

the school staff to take no further steps to obey Judge

McMillan’s desegregation decree.13 (App. No. 281, p. 925a;

App. No. 444, p. 31.)

B. The statute unconstitutionally interferes with the school

board’s affirmative duty to dismantle the dual system.

The court below correctly concluded that the purpose and

effect of section 115-176.1 was to prevent school boards in

North Carolina from performing their affirmative consti

tutional duties to implement Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954), (Brown I), Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) (Brown II), and Green v. County

School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968).

We believe that the court below was so plainly correct in

applying this Court’s decisions to invalidate the section

that the case merits either summary affirmance or dismissal

of the appeal.* *

13 The school board in 1969 took the view that §115-176.1 did not

affect their discretion to adopt a plan to close inner city black

schools and bus the pupils to white schools. (Swann, supra, 306 F.

Supp. at 1295; App. No. 281, p. 585a).

* See Motion to Affirm or Dismiss filed herein.

27

The Green case held—in language applicable to Charlotte

—that boards “ operating state compelled dual systems were

. . . clearly charged with the affirmative duty to take what

ever steps might be necessary to convert to a unitary sys

tem in which racial discrimination would be eliminated

root and branch” (391 U.S. at 437-438). Boards are re

quired by Green to eliminate racially identifiable segre

gated schools and to “ fashion steps which promise real

istically to convert promptly to a system without a ‘white’

school and a ‘Negro’ school, but just schools” (379 U.S.

at 442). The Attorney General of North Carolina, in

defending the anti-busing law, directly challenges the hold

ing in Green in his brief in this Court:

There is no way, considering the relation of the num

ber of blacks to the number of whites, to establish

schools “ in which there are no white schools and no

Negro schools but just schools.” (Appellants’ Brief, p.

16.)

The Attorney General argues that §115-176.1 directs the

“ establishment of reasonable attendance areas and the

preservation of the so-called ‘neighborhood school . . .

[with] transportation of pupils on a nonraeial basis. . .

(Appellants’ Brief, p. 16; emphasis added). The statute

attempts to limit the remedies available to a school board

or a federal court to change the dual system to freedom

of choice plans, voluntary busing plans, or some kind of

geographic zoning (variously called—by the appellants and

the court below— “neighborhood” zoning, “ reasonable” zon

ing, “non-gerrymandered” zoning, or zoning to the school

nearest pupil’s homes).

The three-judge court concluded that notwithstanding

the federal courts’ deference to such an expression of state

legislative policy in favor of “neighborhood schools” , such

28

a policy could not override the duty imposed by Brown and

Green. Where—as in Charlotte— a “neighborhood” assign

ment policy cannot dismantle the state-created dual school

system and eliminate all-black schools, a law which com

pels a neighborhood plan is simply a segregation law. In

Charlotte, where all-black schools in black neighborhoods

have been created by the acts of the school board and other

governmental agencies, a requirement of neighborhood

schools is simply a requirement for black schools in direct

disobedience of Brown I. School desegregation plans must

be designed so that they will work to dismantle state-

created dual systems of separate white and black schools.

A “neighborhood” policy or law which preserves the pat

tern of separate black and white schools is in direct oppo

sition to Green as the Attorney General’s brief has sub

stantially admitted in the passage quoted above. Similarly,

the statutory prohibition against use of school transporta

tion facilities to eliminate racial identifiability of schools is

equally in conflict with Green.

The provision to prohibit busing to desegregate the

schools—except where pupils submit voluntarily to busing

—contravenes the mandate of Green that boards take

“whatever steps might be necessary to convert to a unitary

system” (Green, supra, 391 U.S. at 437-438). Judge Mc

Millan found that the use of the transportation system

was necessary in order to afford a desegregated education

to black children in certain Charlotte neighborhoods. The

state may not enact a law forbidding that which is neces

sary to be done to obey the mandate of Brown I. The con

tent of the statute’s ban on busing is sufficiently vague that

it affords little guide to differentiating legal busing- from

illegal busing. The net effect is to leave the matter of

busing to the discretion of school boards. But despite the

normal area of school board discretion about such matters

29

the ultimate decision about whether facilities which are

necessary to integrate the school will be used cannot be

left as a matter of discretion. Green requires that the

boards do whatever is necessary to dismantle the dual sys

tem of black schools and white schools and eliminate ra

cially identifiable schools where black pupils are set apart.

Section 115-176.1 would prevent the use of a variety of

assignment methods and techniques which are being widely

used to desegregate school systems. The law threatens to

interfere with such techniques as school closing and con

solidations, rezoning methods and techniques (zones de

signed to promote integration, non-contiguous zones),

grade structure changes, the use of pairing and clustering

techniques, and the control of school sizes by use of port

able classrooms, building sizes, and site location when these

methods are used for the purpose of controlling the racial

composition of school populations. The Fourth Circuit has

decided in the Charlotte case that all such methods must

be considered in evaluating the available alternatives to de

segregate the schools. We believe that the court was correct

in viewing these techniques as appropriate remedies con

sistent with the “practical flexibility” mandated by Brown

II (349 U.S. 294, 300) (App. No. 281, p. 1274a). Section

115-176.1 seeks to deprive the boards and courts of the

necessary flexibility to accomplish the needed reforms.

The North Carolina Attorney General complains that

the court below fails to define the constitutional objective

of a unitary school system. But neither the Attorney

General’s Brief nor the anti-busing law suggests any prin

ciple of law for deciding such matters except that school

boards be left alone to decide for themselves how much

desegregation to accomplish. The entire appeal for a

“neighborhood school” system—which has never existed

in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg system—is in reality an

30

appeal for the courts to let the school boards use their

control and their discretion to define school attendance.

The “neighborhood school system” is primarily a political

slogan, and the appellants seek to have the matter of

eliminating school segregation resolved in the political

process by elected school boards. The constitutional rights

of black children under the Brown decision may not, under

our constitutional system of protection for the individual

rights of minority group members, be left to depend upon

whether segregationists can win school board elections.

A three-judge court in Alabama recently invalidated a

statute which forbids assignment “for the purpose of

achieving equality in attendance or increased attendance

or reduced attendance, at any school, of persons of one or

more particular races” etc. Alabama v. United States, ——

F.Supp------ (S.D.Ala. Civil No. 5935-70-P, June 26, 1970)

(reproduced infra, Appendix B). That statute which is

similar in effect to §115-176.1 was rejected on the same

grounds relied upon by the court below. The Alabama dis

trict court was of the unanimous opinion that the statute did

not even present a substantial question as it was foreclosed

by prior decisions of this Court.

C. The Appellants’ Argument Supporting the Statute Rests on

a rejected view that there is no affirmative duty to desegre

gate the schools.

The Attorney General of North Carolina relies on the

idea that school authorities have no affirmative duty to

bring about integration of segregated schools. He cites the

doctrine of Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F.Supp. 776 (E.D.S.C.

1955), a doctrine which has been thoroughly repudiated by

this Court’s decision in Green, supra, as well as by the

Fourth and Fifth Circuits. See e.g. Walker v. County

School Board of Brunswick Cty., 413 F.2d 53, 54, note 2

31

(4th Cir. 1969); and United States v. Jefferson County

Board of Education, 372 F.2d 836, 846, 862-866 (5th Cir.

1966), affirmed on rehearing en banc, 380 F.2d 385, 389

(5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied sub nom. Caddo Parish School

Board v. United States, 389 U.S. 840 (1967). The Green

case made it clear that school boards must take affirmative

action to root out segregation and “disestablish” the segre

gated systems. It is the result—whether a plan actually

works to integrate the schools'—that determines the ade

quacy of a plan to satisfy the constitutional mandate.

The appellants seek to find support for the anti-busing

law in the Brown case itself by arguing that Brown rests

on the premise that schools must be run on a color-blind

basis. They argue that the use of color-conscious techniques

to bring about school integration offends not only the anti

bussing law, but the Fourteenth Amendment as well.14 15

The appellants’ argument entirely ignores this Court’s

recent holding—which must be taken as a repudiation of

the idea that remedies for discrimination must be color

blind—in United States v. Montgomery County Board of

Education, 395 U.S. 225 (1969). The case is not even cited

in the Appellants’ Brief.16 The Montgomery County deci

sion approved a district judge’s use of specific numerical

goals for faculty integration as a remedial technique neces

sary to accomplish the ultimate objective of eliminating

the racial identifiability of faculties in a segregated system.

14 When a litigant sought to use the Constitution to nullify a law

against employment discrimination Mr. Justice Frankfurter wrote

that “ To use the Fourteenth Amendment as a sword against such

State power would stultify that amendment.” Railway Mail Asso

ciation v. Corsi, 326 U.S. 88, 98 (1945) (concurring opinion). Mr.

Justice Reed called the argument “A distortion of the policy mani

fested in that amendment.” (326 U.S. at 94) That same idea ap

plies to appellants’ argument.

15 Appellants do however attack the requirement of faculty inte

gration. Appellants’ Brief pp. 24-25.

That decision necessarily rests on the premise that a

remedial technique which is color-conscious does not offend

the equal protection clause when it is used to eliminate

school segregation. The Montgomery County decision em

phasized the practical problems of a district judge seeking

to eliminate an entrenched system of segregation. That

difficult task cannot be accomplished by self-induced blind

ness to the race of the people in a segregated system. The

appellants’ argument that race cannot be considered in

integrating the schools has been rightly rejected in a host

of school desegregation decisions in the lower federal

courts.16

The appellants attempt to support their argument by

analogy from jury discrimination cases (Appellants’ Brief,

pp. 23-24). Judge Brown’s opinion in Brooks v. Beto, 366

F.2d 1 (5th Cir. 1966; en lane), cert, denied 386 U.S. 975

(1967) deals with the precise problem. Holding that real

ism required a consideration of race in reforming a jury

system which had previously excluded Negroes, Judge

Brown wrote:

“Although there is an apparent appeal to the osten

sibly logical symmetry of a declaration forbidding race

consideration in both exclusion and inclusion, it is both

theoretically and actually unrealistic. Adhering to a

formula which in words forbids conscious awareness

of race in inclusion postpones, not advances, the day 16

16 Wanner v. County School Board of Arlington County, 357

F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1966) ; Dowell v. Board of Education of the

Oklahoma City Public Schools, 244 F. Supp. 971, 981 (W.D.Okla.

1965), affirmed 375 F.2d 158, 169-170 (10th Cir. 1967), cert, denied

387 IT.S. 931 (1967); United States v. Jefferson County Board of

Education, 372 F.2d 836, 876-877 (5th Cir. 1966), affirmed on re

hearing en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied sub nom.

Caddo Parish School Bd. v. United States, 389 U.S. 840 (1967) ;

Youngblood v. Board of Public Instruction of Bay County, No.

29369 (5th Cir. July 24, 1970) ; United States v. Board of Public

Instruction of Polk County, 395 F.2d 66 (5th Cir. 1968).

33