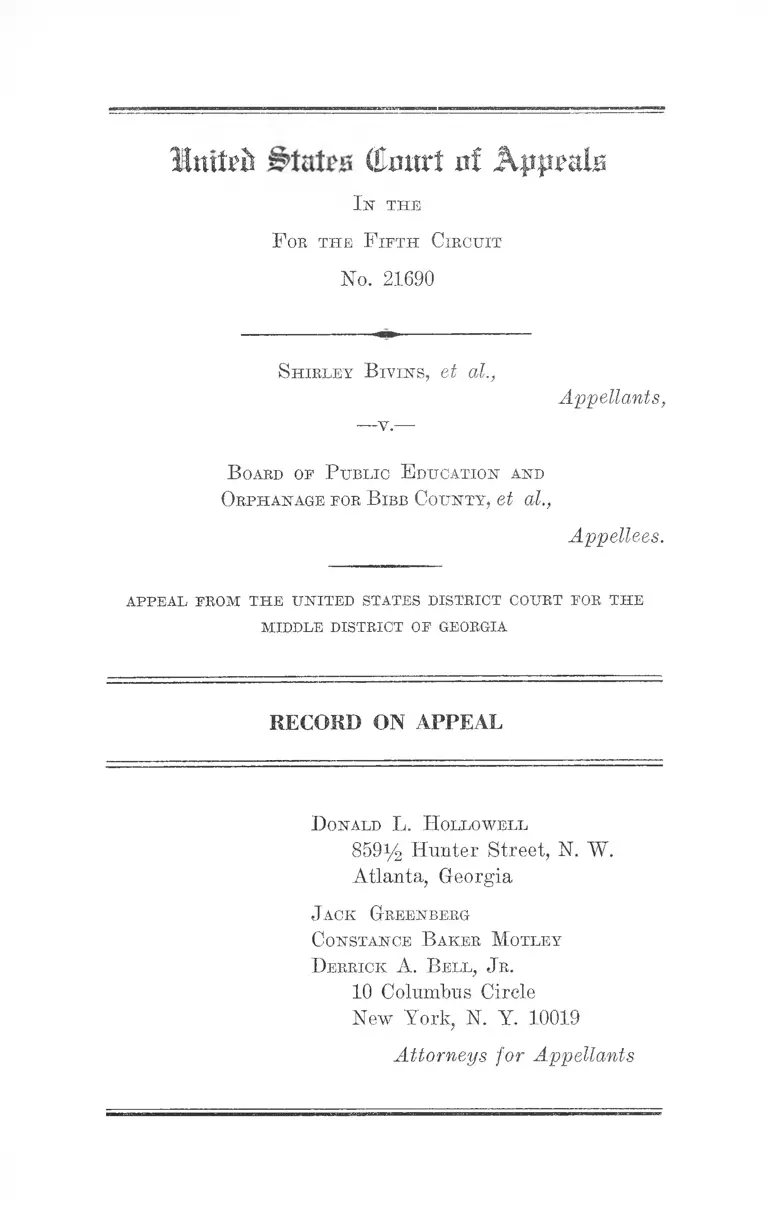

Bivins v. Board of Public Education and Orphanage for Bibb County Record on Appeal

Public Court Documents

May 25, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bivins v. Board of Public Education and Orphanage for Bibb County Record on Appeal, 1964. 872fa6e6-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/404fec59-3b36-47c2-8c77-7a053a0c14b7/bivins-v-board-of-public-education-and-orphanage-for-bibb-county-record-on-appeal. Accessed February 15, 2026.

Copied!

Inttefc (Emtrt 0! Appmh

I n t h e

F or t h e F if t h C ircu it

No. 21690

S h ir ley B iv in s , et al.,

—v.—

Appellants,

B oard of P ublic E ducation and

Orphanage for B ibb County , et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM TPIE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

RECORD ON APPEAL

D onald L. I I ollowell

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

J ack Greenberg

C onstance B aker M otley

D errick A. B ell, J r .

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Complaint ........................................................ ............. -

Motion for Preliminary Injunction -...........................

Answer .................................... .......................................

Order of January 24, 1964 .................................. ..........

Defendant Board’s Plan of Desegregation ...... ..........

Plaintiffs’ Objections to Board’s Desegregation Plan ..

Plaintiffs’ Plan of Desegregation ................................

Transcript of Hearing on April 13, 1964 ........... ..... ....

Colloquy of Court and Counsel___ ___ _______

Summary of Plaintiffs’ Objections to Plan ..........

1

13

16

26

30

37

40

42

42

46

Appellants’ Witnesses:

Julius L. Gfholson

Cross ......................................................... 52

D irect..................................................... 74

Recross ..................................................... 75

Judge Mallory C. Atkinson

Cross ......................................................... 76

11

PAGE

Defendants’ Witnesses:

Judge Mallory C. Atkinson

D irect........................................................... 87

Cross .......................................................... 103

Redirect....................................................... 109

Recross ...................................................... 115

Wallace Miller, Jr.

D irect...................................-............... ...... 117

Cross ..................................... 137

Redirect....................................................... 143

Recross ....................................................... 143

Dr. Leon R. Culpepper

D irect.......................................................... 146

Cross .......................................................... 160

Redirect...................................................... 170

Recross ...................................................... 171

Julius L. Cliolson

D irect.......................................................... 172

Resumed

D irect............................... -......................... 204

Cross .......................................................... 206

Redirect....................................................... 230

Dr. H. GL Weaver

D irect.......................................................... 197

Cross .......................................................... 201

Raymonde M. Kelley

Direct .......................................................... 233

Cross .......................................................... 239

Ill

PAGE

Defendants’ Exhibits ............................ -............... 253

Plaintiffs’ Argument................................................ 261

Defendants’ Responsive Argument .................... — 275

Opinion and Order of April 27, 1964

Notice of Appeal ............................. 298

Isr t h e

Ilnxtvb iistrirt (Umtrt

F or t h e M iddle D istrict of Georgia

Macon Division

Civil Action No. 1926

S h irley B ivin s , J ames B iv in s , L arry B ivins an d F ra n k lin

B iv in s , m in o rs , by H ester L . B iv in s , th e ir m o th e r an d

n ex t fr ie n d ,

and

S olomon B o uie , Glory A n n B ouie a n d D orothy M ae B ogie,

m in o rs , by R ev. W ill ie R. B ogie, th e ir f a th e r an d n ex t

fr ie n d ,

and

J oyce D ickey , m in o r, by R ev. E. Grant D ickey ,

h e r f a th e r a n d n ex t fr ie n d ,

and

H elen G oodrgm, L ela Goodrgm, T homas Goodrgm, J ohn

Goodrgm an d Jo A n n G oodrgm, m in o rs , by T homas

Goodrgm, th e ir f a th e r an d n e x t fr ie n d ,

and

P atricia A n n H arper, m in o r, by A be H arper,

h e r f a th e r an d n ex t fr ien d ,

and

Charlie B ell W illiam s , S ara J eannette W illiam s and

T om m ie L ee W illiam s , minors, by M rs. V ada D. H arris,

their mother and next friend,

an d

2

Complaint

A lice M aeie H aet, m in o r, by M rs. W ill ie M ae H art,

h e r m o th e r an d n ex t fr ie n d ,

an d

P aul H il l , J r ., Cly ne H ill , B ern estin e H ill an d L ucy

M ae H udson, m in o rs , b y I nez H il l , th e ir m o th e r an d

n e x t fr ie n d ,

an d

Carolyn H olston, M elvin H olston, L yre H olston, M axine

H olston, an d E arnestine H olston, m in o rs , b y H enry

H olston, th e ir f a th e r a n d n ex t fr ie n d ,

an d

S olomon H u g h es , III, m in o r, b y S olomon H u g h es , J r .,

h is fa th e r an d n ex t fr ie n d ,

an d

B ill y J oe L ew is , H arold M artin L ew is , Y vonne D ian n e

L ew is , R ay Charles L ew is an d E stella M arie L ew is ,

m in o rs , by M r. R ay L ew is , th e ir f a th e r an d n e x t fr ie n d ,

an d

M errit J o h nso n , th e ir f a th e r a n d n e x t f r ie n d ,

M errit J ohnso&, th e ir f a th e r a n d n ex t fr ie n d ,

an d

W ill ie H oward, J r ., D elores H oward, an d R andolph

H oward, m in o rs , b y G ertrude H oward, th e ir m o th e r

a n d n e x t fr ie n d ,

an d

3

Complaint

D elmarie MoDow, minor, by W yatt J. McDow,

her father and next friend,

an d

Lois F armer, L arry S tewart, M axine S tewart, J oe L.

S tewart and L olita R utland , m in o rs , by D orothea

S tewart, their mother and next friend,

Plaintiffs,

B oard oe P ublic E ducation of B ibb County , Georgia, H. G.

W eaver, President, M allory C. A t k in so n , Vice Presi

dent, W allace M iller , J r., Secretary, W illiam P. S im

mons, Treasurer, George P. R a n k in , J r., H erbert F.

B irdsey, C harles C. H eetw ig , A lbert S. H atcher , J r.,

F rank M. W illin g h a m , W illiam A. F ick lin g , Sr,,

R obert A. M cC ord, J r., and R a lph E ubanks , Members,

H on . W alter C. S tevens, Mayor E dgar H . W ilson ,

Judge Oscar L . L ong and Judge H al B ell , Ex-Officio

Members, and J u liu s L. Gohlson , Superintendent,

Defendants.

C om plaint

1.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to the

provisions of Title 28, United States Code, Section 1343(3),

this being a suit in equity, authorized by law, Title 42,

United States Code, Section 1983, to be commenced by any

citizen of the United States or other person within the

jurisdiction thereof to redress the deprivation, under color

4

Complaint

of statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or usage of a

State, of rights, privileges and immunities secured by the

Constitution and laws of the United States. The rights,

privileges and immunities sought to be secured by this ac

tion are rights, privileges and immunities secured by the

due process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, as

hereinafter more fully appears.

2.

This is a proceeding for a preliminary and permanent

injunction enjoining the Board of Public Education of Bibb

County, Georgia, its members and its Superintendent of

Schools, Julius L. Gohlson, from continuing their policy,

practice, custom and usage of operating a dual school sys

tem in Bibb County, Georgia, based wholly on the race and

color of the children attending schools in said county.

3.

The plaintiffs in this case are Shirley Bivins, James

Bivins, Larry Bivins and Franklin Bivins, minors, by

Hester L. Bivins, their mother and next friend; Solomon

Bouie, Glory Ann Bouie and Dorothy Mae Bouie, minors,

by Rev. Willie R. Bouie, their father and next friend; Joyce

Dickey, minor, by Rev. E. Grant Dickey, her father and

next friend; Helen Goodrum, Lela Goodrum, Thomas Good-

rum, John Goodrum and Jo Ann Goodrum, minors, by

Thomas Goodrum, their father and next friend; Patricia

Ann Harper, minor, by Abe Harper, her father and next

friend; Charlie Bell Williams, Sara Jeannette Williams and

Tommie Lee Williams, minors, by Mrs. Yada. D. Harris,

their mother and next friend; Alice Marie Hart, minor, by

Mrs. Willie Mae Hart, her mother and next friend; Paul

5

Complaint

Hill, Jr., Clyne Hill, Bernestine Hill and Lucy Mae Hudson,

minors, by Inez Hill, their mother and next friend; Carolyn

Holston, Melvin Holston, Lyre Holston, Maxine Ilolston,

and Earnestine Holston, minors, by Henry Holston, their

father and next friend; Solomon Hughes, III, minor, by

Solomon Hughes, Jr., his father and next friend; Billy Joe

Lewis, Harold Martin Lewis, Yvonne Dianne Lewis, Eay

Charles Lewis and Estella Marie Lewis, minors, by Mr. Bay

Lewis, their father and next friend; Merrit Johnson, Jr.,

and Pamela Sue Johnson, minors, by Merrit Johnson, their

father and next friend; Willie Howard, Jr., Delores

Howard and Randolph Howard, minors, by Gertrude How

ard, their mother and next friend; Delmarie McDow, minor,

by Wyatt J. McDow, her father and next friend; and Lois

Parmer, Larry Stewart, Maxine Stewart, Joe L. Stewart

and Lolita Rutland, minors, by Dorothea Stewart, their

mother and next friend. Plaintiffs are all members of the

Negro race and bring this action on their own behalf and

on behalf of all other Negro children and their parents in

Bibb County who are similarly situated and affected by the

policy, practice, custom and usage complained of herein.

Plaintiffs are all citizens of the United States and the

State of Georgia, Bibb County, Georgia. The minor plain

tiffs and other minor Negro children similarly situated are

eligible to attend the public schools of Bibb County which

are under the jurisdiction, management and control of the

defendant Board, but from which the plaintiffs and all

other Negro children similarly situated have been segre

gated because of their race pursuant to the policy, prac

tice, custom and usage of the defendant Board. The mem

bers of the class on behalf of whom plaintiffs sue are so

numerous as to make it impracticable to bring them all in

dividually before this Court, but there are common ques

tions of law and fact involved, common grievances arising

6

Complaint

out of common wrongs and common relief is sought for

each member of the class. The plaintiffs fairly and ade

quately represent the interests of the class.

4.

The defendants in this case are the Bibb County Board

of Education. The members of said Board are H. G.

Weaver, President, Mallory C. Atkinson, Vice-President,

Wallace Miller, Jr., Secretary, William P. Simmons,

Treasurer, George P. Rankin, Jr., Herbert F. Birdsey,

Charles C. Hertwig, Albert S. Hatcher, Jr., Frank M. Wil

lingham, William A. Fickling, Sr., Robert A. McCord, Jr.,

and Ralph Eubanks. Hon. Walter C. Stevens, Mayor,

Edgar H. Wilson, Judge Oscar L. Long and Judge Hal

Bell are Ex-Officio Members. Julius L. Gohlson is Super

intendent. The defendant Board maintains and generally

supervises the public schools in Bibb County, Georgia, act

ing pursuant to the direction and authority contained in

the State’s constitutional provisions and statutes, and as

such are officers and agents of the State of Georgia enforc

ing and exercising state laws and policies.

5.

Plaintiffs allege that the defendants, acting under color

of the authority vested in them by the laws of the State of

Georgia, have pursued and are presently following pur

suant to and under color of state law, a policy, custom,

practice and usage of operating the public school system of

Bibb County, Georgia, on a basis that discriminates against

plaintiffs and other Negroes similarly situated because of

race or color, to w it:

(a) The defendant Board maintains and operates the

public schools in Bibb County, Georgia, all of which schools

7

Complaint

are operated on a completely segregated basis. None of

the approximately 11,000 Negro children residing within

the County, and eligible to attend the public schools have

ever been assigned by the Board to attend white schools,

and in accordance with this policy, practice and custom,

each of the minor plaintiffs is assigned to one of approxi

mately 16 Negro schools, some of which are located further

from their homes than schools limited to whites. In simi

lar fashion, all of the approximately 19,000 white children

residing within the County, and eligible to attend the pub

lic schools, have been assigned by the Board only to the

34 white schools. Teachers, principals and other profes

sional personnel are assigned by the defendant Board on

the basis of race so that Negro teaching personnel are as

signed to Negro schools and white teaching personnel are

assigned to white schools. Bus transportation is provided

on a racially segregated basis, and all curricula and extra

curricular activities and school programs are conducted on

a racially segregated basis. All budgets and other funds

appropriated and expended by defendants are appropri

ated and expended by defendants separately for Negro and

white schools.

(b) The defendant Board on several occasions has been

placed on notice that plaintiff's and members of their class

wish to have the Bibb County public schools desegregated

in accordance with the Supreme Court’s school desegrega

tion decision of 1954.

(c) In December 1954, a petition calling on the Board to

desegregate the schools was submitted by Negro citizens

of Bibb County. In response to this petition, the Board

promised to hold a hearing when such meeting would be

constructive and proper. To plaintiff’s knowledge, no such

hearing was ever held.

Complaint

(d) In August 1955, a second petition signed by Negro

parents and citizens was submitted to the Board again call

ing for an end to racially segregated schools in Bibb

County. The defendant Board referred this petition to a

special committee headed by defendant Board member Mal

lory C. Atkinson. To plaintiffs’ knowledge, no action by

this Board was ever made public.

(e) In February 1961, the Macon Council on Human Re

lations, an interracial group, appealed to the defendant

Board to study the school situation for the purpose of

initiating desegregation of the public schools.

(f) In or about March 1963, a group of Negro citizens,

including some of the plaintiffs, again petitioned the de

fendant Board to desegregate the Bibb County public

schools, as a result of which action, the defendant Board,

on April 25, 1963 filed a petition seeking a declaratory

judgment in the Bibb County Superior Court as to whether

the Board had the power to desegregate the schools in

view of its charter from the State which prescribes the

operation of a system of distinct and separate schools for

white and colored children.

(g) The Bibb Superior Court ruled that the defendant

Board has authority under its charter to operate its schools

on a desegregated basis. However, the Board, with four

members dissenting, adopted a Resolution stating that any

decision to change the present segregated operation of the

Bibb County public schools must be left to the federal

courts, and reaffirming the Board’s “ . . . sincere and deep

conviction that integration of the races in the public schools

of Bibb County will be detrimental to both the colored and

white races, and the entire county. The responsibility for

and consequences of any such action rests upon others

than this Board.”

9

Complaint

6.

Plaintiffs allege that the policy, custom, practice and

usage of the defendant Board in requiring the minor plain

tiffs and other Negro children similarly situated to attend

racially segregated schools in Muscogee County violates

rights secured to plaintiffs and others similarly situated by

the equal protection and due process clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

and Title 42, United States Code, Section 1983.

7.

Plaintiffs and other Negro citizens have made every

effort, as set forth above, to communicate their dissatisfac

tion with segregated schools to the defendant Board but to

no avail. Indeed, the defendant Board is now on record as

opposing any desegregation of the Muscogee County pub

lic schools, and refusing to initiate desegregation unless

such action is required by order of the federal courts.

8.

Plaintiffs and each of them and those similarly situated

have suffered and will continue to suffer irreparable in

jury and harm caused by the acts of the defendant Board

herein complained of. They have no plain, adequate or

complete remedy to redress these wrongs other than this

suit for injunctive relief. Any other remedy would be

attended by such uncertainties and delays as to deny sub

stantial relief, would involve a multiplicity of suits, cause

further irreparable injury and occasion damage, vexation

and inconvenience to the plaintiffs and those similarly situ

ated.

10

Complaint

W herefore , plaintiffs respectfully pray that this Court

grant the following relief:

1. Advance this cause on the docket and order a speedy

hearing of plaintiffs’ motion for preliminary injunction

which is filed simultaneously with the filing of this com

plaint and grant the relief prayed for therein.

2. Order a speedy trial of the merits of this case.

3. Upon the conclusion of the trial, issue a permanent

injunction forever restraining and enjoining the defen

dants, the Bibb County School Board, its members, em

ployees and successors, and the Superintendent of Schools

of Bibb County, his agents, employees and successors, and

all persons in active concert and participation with the de

fendants from:

(a) continuing to operate a dual school system in Bibb

County, Georgia, based wholly upon the race and color of

the children attending school in Bibb County;

(b) continuing to assign children to school in Bibb

County on the basis of race and color;

(c) continuing to assign teachers, principals, supervisors

and other professional school personnel to the schools of

Bibb County on the basis of race and color of the person-

ney to be assigned and the race and color of the children

attending the particular school to which the assignment

is made;

(d) continuing to designate certain schools as Negro

schools and white schools;

(e) continuing to appropriate funds, approve curricula

and extra-curricular activities and other school programs

11

Complaint

which are limited on the basis of race or discriminatory on

the basis of race;

(f) continuing to construct schools which are to be lim

ited to attendance by one or the other racial group;

(g) making any other distinctions based wholly upon

race and color and in the operation of the public school

system of Bibb County.

In the alternative, plaintiffs pray that this Court direct

defendants to submit a complete plan, within a period of

time to be determined by this Court, for the reorganiza

tion of the entire school system of Muscogee County,

Georgia, into a unitary non-racial system which shall in

clude a plan for the reassignment of all children presently

attending the public schools of Bibb County on a non-racial

basis and which will provide for the future assignment of

children to school on a non-racial basis, the assignment of

teachers, principals, supervisors and other professional

school personnel on a non-racial basis, the elimination of

racial designations as to schools, the elimination of all

racial designations in the budgets, appropriations for

school expenditures, and all plans for the construction of

schools, and the elimination of racial restrictions on certain

curricula and extra-curricular school activities, and the

elimination of any other racial distinction in the operation

of the school system in Bibb County which is based wholly

upon race and color.

4. Plaintiffs pray that this Court retain jurisdiction of

this case pending the transition to a unitary non-racial sys

tem.

5. Plaintiffs pray that this Court will grant them their

costs herein, reasonable attorney fees for those counsel re

questing same, and grant such other, further, additional

12

Complaint

or alternative relief as may appear to a court of equity to

be equitable and just.

D onald L. H ollowell

859V2 Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta 14, Georgia

T homas J ackson

845 Forsyth Street

Macon, Georgia

J ack Gbeenbebg

Constance B a k es M otley

D ebbick A. B ell , J b .

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

13

Motion for Preliminary Injunction

[C aption Om itted ]

Plaintiffs move this Court for a preliminary injunction,

pending the final disposition of this cause, and as grounds

therefor rely upon the allegations of their complaint and

show the following:

1. Plaintiffs continue to he assigned and forced to at

tend racially segregated schools operated by the defendants

pursuant to state policy, practice, custom, and usage as

set forth in the complaint.

2. Plaintiffs’ constitutional rights are violated by such

assignment and attendance at racially segregated schools.

3. Plaintiffs and other Negro citizens have petitioned

the defendants in vain to initiate desegration of the Bibb

County public schools in compliance with the United States

Supreme Court school desegregation decision of 1954.

4. Defendants are now on record as favoring the main

tenance of segregated schools, notwithstanding the deci

sion of the United States Supreme Court in 1954, and have

given notice that they will not initiate desegregation unless

ordered to do so by the federal courts.

5. Plaintiffs are irreparably harmed by the defendant

Board’s continued failure either to desegregate the public

schools under its jurisdiction or submit a plan for the re

organization of said school system on a unitary nonracial

basis, and, in addition to the desegregation plan finally

approved by this Court, should be admitted upon request

to the nearest white school at the beginning of the second

semester of the 1963-64 school year.

14

Motion for Preliminary Injunction

W herefore , plaintiffs respectfully pray that this Court

advance this cause on the docket and order a speedy hear

ing of this action according to law and after such hearing:

1. Enter a decree enjoining defendants from refusing

to admit each of the plaintiffs upon request at the beginning

of the second semester of the 1963-64 school year to the

nearest white school to their residences which they are

eligible by grade to attend;

2. Enter a decree enjoining defendants, their agents,

employees, successors, attorneys, and all persons in active

concert and participation with them from: (1) maintaining

a dual scheme or pattern of school zone lines or attendance

area lines based on race and color, (2) assigning pupils to

schools in Bibb County on the basis of race and color of

the pupils, (3) assigning teachers, principals and other

professional school personnel to the Bibb County schools

on the basis of race and color of the person assigned and

the race and color of the children attending the school to

which such personnel is to be assigned, (4) approving

budgets, making available funds, approving employment

and construction contracts, and approving policies, cur

ricula and programs designed to perpetuate or maintain

or support compulsory racially segregated schools.

In the alternative, plaintiffs pray that this Court enter

a decree directing defendants to present a complete plan,

within a period of time to be determined by this Court,

for the reorganization of the entire school system of Bibb

County into a unitary nonraeial system which shall include

a plan for the assignment of children on a nonraeial basis;

the assignment of teachers, principals and other profes

sional school personnel on a nonraeial basis; the drawing

of school zone or attendance area lines on a nonraeial basis;

15

Motion for Preliminary Injunction

the allotment of funds, the construction of schools, the

approval of budgets on a nonracial basis; and the elimina

tion of any other discrimination in the operation of the

school system or in the school curricula which are based

solely upon race and color. Plaintiffs pray that if this

Court directs defendants to produce a desegregation plan

that this Court will retain jurisdiction of this ease pending

court approval and full and complete implementation of

defendants’ plan.

Plaintiffs pray that this Court will allow them their

costs herein, reasonable attorney fees for those counsel

requesting same, and grant such further, other, additional

or alternative relief as may appear to the Court to be equi

table and just.

D onald L. H ollowell

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta 14, Georgia

T homas J ackson

845 Forsyth Street

Macon, Georgia

J ack Greenberg

C onstance B aker M otley

D errick A. B ell , J r .

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

16

Answ er

[C aption Om itted ]

Come now all of the defendants in the above case and for

answer to the complaint respectfully sho w:

First Defense

1.

Defendant Board of Education, herein for convenience

referred to as the Board, is a body politic and corporate

created and operating as a corporation under a charter

from the State of Georgia. Its correct corporate name is

the Board of Public Education and Orphanage for Bibb

County, and it has full power and authority to sue and be

sued by said name and style.

2.

The Board, as distinguished from its individual mem

bers, is the corporate body charged with the direction and

control of public education in Bibb County, Georgia, and

is the only necessary or proper party defendant in this

proceeding.

3.

The Board admits the jurisdiction of this court, both

as to parties and subject matter, and admits that plaintiffs

as representatives of the class of minor Negro children in

whose behalf they sue adequately represent such class

and are entitled in this proceeding to such order of this

court as will adequately protect the rights, privileges and

immunities of said class, taking into account the adminis

trative and other problems of the Board incident to the

granting of such protection.

17

Answer

4.

As in the ease of any other corporation the orders and

judgments of this court in a proceeding in which the Board

is the only party defendant will effectively constrain the

individual members of the Board and its officers and em

ployees.

W herefore , defendants move that the complaint be

dismissed as to all defendants other than the Board.

Second Defense

1.

Defendants admit that the plaintiffs named in paragraph

3 of the complaint are with negligible exceptions eligible

to attend the public schools of Bibb County and are pres

ently enrolled in the public schools of Bibb County for

the 1963-64 school year.

2.

Defendants deny, however, that any of said minor plain

tiffs has prior to the filing of this petition ever at any time

sought admission to any school heretofore operated for

white children, or requested or sought transfer from the

school to which he or she has been assigned, nor has any

one acting in behalf of any of the minor plantiffs made

such request.

3.

Defendants admit that the Board has heretofore main

tained and operated separate schools for white and colored

children, and defendants admit that on occasions prior to

March, 1963, substantially as alleged in paragraph 5 of the

18

Answer

complaint, one or more relatively small groups of Negro

residents of Bibb County, Georgia, have indicated to the

Board their request as parents and citizens that the Bibb

County school system be reorganized on a racially inte

grated basis. Defendants admit that in or about March,

1963, a communication signed by seven such individuals

was received by the Board in which a meeting with the

Board was requested for the purpose of airing certain

grievances pertaining to public education in Macon and

Bibb County. Said communication of March, 1963, and the

prior communications alleged in paragraph 5 of the com

plaint are in writing and will speak for themselves.

4.

Pursuant to the aforesaid communication of March,

1963, after meeting with said group, and after careful and

deliberate consideration, the Board on April 25, 1963, filed

a petition in the Superior Court of Bibb County seeking

a declaratory judgment as to whether the Board had the

power under its charter from the State to operate other

than distinct and separate schools for white and colored

children, and on or about July 8, 1963, the judgment of

that court was obtained that notwithstanding provisions

of the Board’s charter to the contrary such right and power

did exist.

5.

Prior to the decisions of the Supreme Court of the United

States on May 17, 1954, and May 31, 1955, in Brown v.

Board of Education, and in companion cases decided at

the same time, the concept of separate but equal schools

and other public facilities for white and colored children

19

Answer

was judicially accepted as constituting compliance with all

of the requirements of the Federal Constitution, and the

maintenance and operation of separate schools in the State

of Georgia was actually required by the general laws of

the State. In the light of said decisions, and following

court decisions over a period of years thereafter, all such

general laws of the State of Georgia requiring segregation

of the races were repealed, and at the present time there

are no general laws in Georgia which prevent, whether

valid or invalid, the placing of children of different colors

in the same school.

6.

However, there did remain until the aforesaid declara

tory judgment of July 8, 1963, a provision in the Board’s

charter expressly proscribing the placing of children of

different colors in the same school by the Board, raising

the question whether the Board had the power under its

charter to operate other than separate schools for the

white and colored races. While the Board realized that the

prohibition in its charter was invalid, under decisions of

the Supreme Court of the United States and other Federal

Courts, the Board was uncertain whether it had the power

from the State to act in disregard of said prohibition, or

if it did so act whether its charter would be subject to rev

ocation, and said declaratory judgment proceeding was

voluntarily instituted by the Board to resolve that doubt,

and to establish (1) that it did have the power to operate

desegregated schools notwithstanding the prohibition in

its charter or (2) that it did not have such power, in which

latter event it would have followed that the Board would

have to surrender all of its powers and responsibilities in

20

Answer

respect to public education in Bibb County, returning the

operation of the schools in said County to the State or to

such other agency of the State as might be established for

that purpose. Said declaratory judgment proceeding was

instituted by the Board in a good faith effort on the part

of the Board to resolve and remove any impediment in the

way of desegregating the public schools in Bibb County

insofar as the limitations and prohibitions contained in

the Board’s charter were concerned; with the result that

at the present time there is no statutory or charter impedi

ment which would prevent compliance by the Board with

any proper order of this court.

7.

It is true that following said declaratory judgment the

Board at a meeting on July 30, 1963, resolved by a divided

vote that it would continue its present system of operating

its schools. A copy of said resolution, which discloses the

Board s reasons for such action, is attached hereto marked

Exhibit A and is by reference made a part hereof. Said

action was taken with the knowledge that certain Negro

citizens, presumably to include the seven who had com

municated with the Board in March, 1963, were preparing

to file and would shortly file a petition in this court, as was

actually done on August 14, 1963, though no prior peti

tioner to the Board appears as a party plaintiff in said

action, and in the belief that under all the facts and circum

stances not necessary to be set forth herein it would be

better for all concerned for the Board to act under the

direction and continuing jurisdiction of this court than by

voluntary ex parte action by the Board or by action by the

Board pursuant to negotiations and agreements with a

limited number of Negro citizens.

21

Answer

8.

Defendants aver that for reasons which will in due time

be made to appear to the court, involving administrative

and other problems, any general, arbitrary or immediate

reallocation of pupils in the Bibb County school system

would result in disorganization and would impose intol

erable burdens upon the public school system in Bibb

County and upon the Board and its employees.

9.

Defendants further say, specifically in response to plain

tiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction, that any order

of this court at this time, either preliminary or otherwise,

restraining and enjoining the Board in any respect would

be premature and inappropriate pending the submission

by the Board of a plan of desegregation and the considera

tion of such plan by this court. Defendants say that any

such injunction should be denied, or at least deferred for

future consideration as the circumstances may hereafter

warrant.

10.

Specifically answering paragraph 8 of the complaint de

fendants say that the fact and extent of injury and harm

to plaintiffs and those similarly situated from maintaining

segregated schools is a matter of opinion, and the extent

to which other similarly situated minor children share the

opinions alleged by the plaintiffs is questionable, but since

these are not deemed by defendants to be legitimate mat

ters of defense they make no admissions or denials with

respect thereto. Defendants admit that to the extent that

plaintiffs are entitled to redress such redress should be

afforded by this court in this proceeding.

22

Answer

11.

Defendants deny that they have been litigious, or even

dilatory, and deny that plaintiffs are entitled to be granted

attorneys’ fees for counsel representing them or their

other costs herein.

W herefore , defendants pray that the injunctive relief

sought by the plaintiffs be denied, and that such direction

be given by the court as to the court may seem meet and

proper with respect to the formulation and submission

of a plan to be prepared and submitted by the Board for

the court’s approval.

Respectfully submitted,

C. B axter J oktes

1007 Persons Building

Macon, Georgia

Attorney for Defendants

[Certificate Omitted]

23

EXHIBIT A

R esolution o r t h e B oard oe P ublic E ducation

and Orphanage for B ibb C ounty

This Board of Education was created by Special Act

of the General Assembly of Georgia approved August 23,

1872. One clear provision of the Act was that the Board

shall maintain and operate separate schools for the colored

and white children. This has been done to this day—for

nearly a hundred years. We believe that the wise judg

ment of the founders of this Board, in directing such sepa

rate schools, was sound in 1872 and is sound today.

Several weeks back the Board was advised and notified

that a petition in Federal Court was forthcoming, directed

at ending the long and successful operation of the public

schools of Bibb County on a separate racial basis. Because

of this advice and notification, and because of the clear

mandate of its charter as to separate facilities for white

and colored pupils, this Board was fearful that the Federal

Court might order an end to such separate education of

the races, whereby this Board could not then legally operate

the school system of Bibb County.

In view of this impending situation facing the Board,

the Board invoked a ruling of the State Court, Bibb Supe

rior Court, as to the Board’s authority under its charter

from the State to operate the Bibb school system on a

basis other than separate facilities for the races.

The Bibb Superior Court ruled that the Board had au

thority under its charter to operate its schools other than

on a basis of separate schools for the races.

This ruling of Bibb Superior Court was not invoked

for any reason other than to ascertain if this Board had

authority to operate other than separate schools for the

races, so that the Board would not so do, at the individual

24

Exhibit A

peril of its members if ordered to do so by the Federal

Courts.

If the Bibb Superior Court had ruled that the mandatory

provision in the Board’s charter, to operate only separate

schools for the colored and white races, was such an in

tegral part of the charter that with such provision stricken

the Board had no authority to operate the Bibb school

system, then this Board would be functus officio, with no

authority to operate its schools on any basis other than

separate facilities for the races. A judicial determination

of this Board’s position in the matter was thus necessary,

and was obtained.

The Supreme Court of the United States has declared

that forced separation because of race in public schools is

unconstitutional. That court has not ruled, and no other

court has ruled, that any school or any school system

operated voluntarily on a basis of separation of the races,

or separation on any other basis, is unconstitutional, un

desirable or repugnant to any principle or rule of law,

society or human relations.

We realize that all members of the Federal judicial sys

tem, the judges of the Circuit Courts of Appeals and the

District judges, are required by law and precedent to

adhere to the decrees of the U. S. Supreme Court.

We believe that the U. S. Supreme Court, in its school

cases, realized that the circumstances in various localities

and parts of the Nation, from state to state, and even within

a state, would be different, requiring and justifying differ

ent solutions and methods of fulfilling its decrees, even

realizing that some systems, and its pupils and their par

ents, might desire complete separation of the races in their

schools. Because of this realization, the Supreme Court

has granted local Federal Courts latitude in enforcing its

25

Exhibit A

judgments if and when the matter is submitted to such

local courts.

The Federal District Courts have, by the Supreme Court

of the United States, been made determinators of what

type operation of a public school system meets the require

ments of the Supreme Court decision under the peculiar

circumstances of any particular case, when presented to

the court.

If this Board were to make a determination without the

sanction and approval of the courts, its validity and lasting

effect would be as uncertain as the weather.

Without court sanction and approval, by its order, any

such action taken by this Board, and administrative pro

cedures set up to put into effect, today, this week, or this

month, wrnuld have no assurance of being effective tomor

row, next week or next month.

We reaffirm our sincere and deep conviction, that integra

tion of the races in the public schools of Bibb County will

be detrimental to both the colored and white races, and

the entire county. The responsibility for and consequences

of any such action rests upon others than this Board.

We feel that the vast majority of both our colored and

white citizens of Bibb County are satisfied with the present

system of operation of our schools, and that it would be

contrary to the wishes of such vast majority for this Board

to make any changes in its operation.

We also feel that the public of Bibb County is entitled

to know the position of its Board of Education in this

matter.

T herefore, be it resolved by the Board of Public Edu

cation and Orphanage for Bibb County that this Board

continue its present system of operating its schools.

O rd er o f Jan u ary 24 , 1964

[C aption Om itted ]

In August, 1963, plaintiffs filed their petition in behalf

of themselves and other persons similarly situated against

the named defendants. Plaintiffs have amended their peti

tion so as to eliminate all of the defendants except the

Board of Public Education and Orphanage for Bibb

County. In their petition plaintiffs made allegations to

the effect that the defendants were operating the Public

Schools of Bibb County, Georgia, on a “completely segre

gated basis”, to include the assignment of pupils, teachers,

principals, and other professional personnel, as well as

in the use of bus transportation, the conduct of curricular

and extra-curricular activities and school programs. Plain

tiffs further allege that all budgets and other funds appro

priated and expended by defendants are appropriated and

expended by defendants separately for Negro and white

schools. Plaintiffs, also, allege, in substance, that all efforts

of Negroes to effect desegregation of the Bibb County

Public School System have been to no avail, and that they,

as well as those similarly situated, “have suffered and will

continue to suffer irreparable injury and harm caused by

the acts of the defendant Board herein complained of.”

They also allege that they have no plain, adequate or com

plete remedy to redress their wrongs other than by the

bringing of this suit for injunctive relief, indicating that

any other remedy would be attended by such uncertainties

and delays as to deny substantial relief, among other

things. Plaintiffs then pray for an injunction forever re

straining and enjoining the defendants, the Bibb County

School Board, its members, employees and successors, and

the Superintendent of the Schools of Bibb County, his

agents, employees and successors, and all persons in active

concert and participation with the defendants from:

27

Order o f January 24, 1964

“(a) continuing to operate a dual school system in Bibb

County, Georgia, based wholly upon the race and color

of the children attending school in Bibb County;

“(b) continuing to assign children to school in Bibb

County on the basis of race and color;

“ (c) continuing to assign teachers, principals, super

visors, and other professional school personnel to the

schools of Bibb County on the basis of race and color

of the personnel to be assigned and the race and color

of the children attending the particular school to which

assignment is made;

“ (d) continuing to designate certain schools as Negro

schools and white schools;

“ (e) continuing to appropriate funds, approve curricu

lar and extra-curricular activities and other school pro

grams which are limited to attendance on the basis of

race or discriminatory on the basis of race;

“ (f) continuing to construct schools which are to be

limited to attendance by one or the other racial group;

“ (g) making any other distinction based wholly upon

race and color in the operation of the public school

system of Bibb County.”

In the alternative, “plaintiffs pray that this Court direct

defendants to submit a complete plan, within a period of

time to be determined by this Court, for the reorganization

of the entire school system of Bibb County, Georgia, into

a unitary non-racial system which shall include a plan for

reassignment of all children presently attending the public

schools of Bibb County on a non-racial basis and which

Order of January 24, 1964

will provide for the future assignment of children to school

on a non-racial basis, the assignment of teachers, princi

pals, supervisors and other professional school personnel

on a non-racial basis, the elimination of racial designations

as to schools, the elimination of all racial designation in

the budgets, appropriations for school expenditures, and

all plans for the construction of schools, and the elimina

tion of racial restrictions on certain curricular and extra

curricular school activities, and the elimination of any

other racial distinction in the operation of the school sys

tem in Bibb County which is based wholly upon race and

color.”

The answer of the defendants admits the essential alle

gations of jurisdiction, plaintiffs’ capacity to sue in behalf

of themselves and as representatives of the class of minor

Negro children similarly situated (par. 3, First Defense)

and that the Board has in the past and presently operates

separate schools for white and colored children in Bibb

County (pars. 3 and 7, Second Defense).

Defendants have admitted that plaintiffs as representa

tives of the class of minor Negro children in whose behalf

they sue are entitled in this proceeding to such order of

this Court as will adequately protect the rights, privileges

and immunities of said class, taking into account the ad

ministrative and other problems of the defendant Board

incident to the granting of such protection, and plaintiffs

recognize that the defendant Board should be allowed a

reasonable period of time in bringing about the elimination

of discrimination within the equal protection mandates of

the Constitution.

Accordingly the defendant Board of Education is hereby

ordered and directed to make a prompt and reasonable

29

Order o f January 24, 1964

start towards the effectuation of the transition to a racially

non-discriminatory school system and to present to this

Court on or before the 24th day of February, 1964, a com

plete plan adopted by said Board which is designed to

bring about full compliance with this order and which shall

provide for a prompt and reasonable transition to a

racially non-discriminatory school system in the public

school system of Bibb County, Georgia.

Following the filing of defendant’s plan with this Court

plaintiffs shall have twenty days to file objections to the

plan, if any, after which this Court will set a date, place

and time for hearing evidence and arguments of counsel

for and against said plan and for any further order of this

Court which may then appear meet and proper.

The court retains jurisdiction of this cause for the pur

pose of entering such further orders or granting such

further relief to the plaintiffs as may be necessary, specifi

cally whether or not the defendant Board of Education

shall be enjoined as prayed, and the scope of such injunc

tion, and the Court reserves for further hearing all other

rulings, decisions and protective orders of the court pend

ing compliance by the defendant Board with the foregoing

directive.

This 24th day of January, 1964.

United States Judge

W . A. B ootle

30

F lan o f B oard o f P ub lic E ducation and O rphanage fo r

B ibb County P u rsu a n t to C ourt O rd er o f

Jan u ary 2 4 , 1 9 6 4

[C aption Om itted ]

This Plan is submitted by the Board of Public Education

and Orphanage for Bibb County in compliance with the

order of this court in the above stated case.

As indicated by its pleadings heretofore tiled the Board

has traditionally maintained and operated separate schools

for white and Negro children in the exercise of its direction

and control of public education in Bibb County. In so doing

the Board has been diligent to insure that the separate

facilities so provided would be equal. The Board has taken

and now takes pride in the quality and adequacy of the

public education which it has provided, without distinction

as between the races, and particularly takes pride in the

spirit of harmony and cooperation which has prevailed

among all elements in the county in the accomplishment

within the separate but equal doctrine of a superior educa

tional system for the benefit of all eligible school children

of the county.

Describing generally the local system as it exists today,

there are no school districts as such within the county for

either white or Negro children. The authority to designate

the school or schools to be attended, with the correspond

ing duty, is vested in the Superintendent, subject to estab

lished procedures relating to transfers, none of which is

based on race distinctions except as such distinction is

implicit in the fact that separate schools are provided for

the separate races. It is true, however, that the Superin

tendent is generally guided by recognized residential areas

in placing children in the grammar schools and children

progressing from a grammar school to a high school are

31

Defendant Board’s Plan for Desegregation

generally placed in high school on the basis of the grammar

school from which they graduate. From time to time these

areas are changed or redefined as population or school

census figures shift within the county. It is the eventual

plan of the Board to establish a single unitary system of

residential areas for school placement, without distinction

as to race, but this cannot be accomplished immediately.

In the meantime, and for some time, the Board has fol

lowed a policy of avoiding references to race in its records,

publications and designations, and will continue this policy.

Nevertheless, for identification and other essential pur

poses it is not possible to eliminate all such designations

except as an ultimate objective.

While Negro teachers are traditionally assigned to

schools for Negro children and white teachers to schools

for white children, no distinction based on race is made in

the facilities provided for the several schools or in the

appropriation or expenditure of available funds. The uni

form salary schedule applied usually results in a higher

average rate of compensation for Negro teachers than for

white teachers.

Bus transportation is provided for the school which the

pupil is attending, and is provided on a separate basis only

to the extent that the schools are separate. For practical

purposes this is absolute at the present time, but it will not

remain so as both white and Negro children attend the

same school.

The Board considers it utterly impracticable at the pres

ent time, or within the near future, to reassign teachers,

principals and other professional personnel on any basis

different from the present practice, and does not include

in this plan any proposal to do so. As the plan progresses

that may become partially or wholly practicable and will

32

Defendant Board’s Plan for Desegregation

be studied and considered when the time seems appropri

ate.

It is implicit in the subject which is dealt with in this

proposal that upon the first step being taken in accordance

with the plan hereby proposed, or even in anticipation

thereof, frictions and conflicts may arise of more or less

severity, but the Board is resolved and pledges itself to

act with responsible planning and with continuing and

complete obedience to the orders and directions of this

court in bringing about the transitions herein proposed.

The Board anticipates the full cooperation of the enforce

ment officers of the local and state governments, and will

lend its best effort to creating a climate which will avoid,

or as far as possible minimize, any disruption of the school

program by reason of such possible frictions or conflicts.

It is the carefully considered opinion of the Board that

any plan submitted by or imposed upon the Board should

be implemented gradually over a reasonable period of time,

and in progressive steps starting at the 12th grade and

thereafter extending at successive intervals to the 1st

grade, eventually including the entire system.

The vocational school program in Bibb County is admin

istered by the local Board as an agency of the State Board,

and the Board has neither the full responsibility nor the

duty with respect to the vocational system as it has with

reference to the public school system in Bibb County.

Nevertheless the Board feels that the vocational schools in

Bibb County should be included and dealt with in this plan.

In keeping with the traditional separate school pattern

classes and programs for vocational training have gener

ally been separately provided for white and Negro trainees,

but this distinction has not been rigidly followed and is

not absolute at the present time. It is a part of the pro-

33

Defendant Board’s Plan for Desegregation

posed plan that no applicant will be denied admission in

the future to any vocational program under the control of

the Board, or transfer from one program to another, solely

because of his or her race.

In the light of the foregoing, and in accordance there

with, the following plan is submitted:

P L A N

(1) The responsibility for and the duty of designating

the school or schools to be attended within the system will

continue to be vested in the Superintendent, subject to the

responsibility and duty of the Board to give overall direc

tion and supervision and to the Board’s final jurisdiction

on appeal from a decision of the Superintendent.

(2) No immediate change will be made in the identifica

tion of residential areas or in the identification of the high

school to which pupils graduating from the several gram

mar schools are assigned, though these designations are

subject to change from time to time as availability of space

and pupil distribution among the existing schools make

necessary. Except as indicated by subsequent paragraphs

hereof, the present policies and procedures of the system

will be continued with respect to the placement of pupils

entering the system and with respect to the transfer of

pupils within the system. Pupils will register for new

terms at the school which they last attended. The proce

dures presently in effect will from time to time be reviewed

and from time to time revised, to provide adequate or more

adequate opportunity for the pupils or their parents or

guardians to express their preferences, whether upon enter

ing the system for the first time or in respect to transfers,

to the end that all such expressions of preference will be

34

Defendant Board’s Plan for Desegregation

speedily considered and acted upon. They will provide full

implementation of the plan and as set forth in paragraphs

(4) and (6) hereof will be applied without distinction or

discrimination because of race.

(3) In acting upon pupil requests for original assign

ments or for transfers the Superintendent will take into

account the factors which presently guide him in the place

ment of pupils and those which are in accordance with

sound and generally observed practices in the field of pub

lic school education throughout the country, with a view to

the establishment, maintenance and operation of a public

school system in Bibb County of the highest attainable

caliber and quality for the benefit of all of the children of

the county, and with a view toward the eventual elimina

tion of compulsory racial segregation in all grades within

the system.

(4) The Board will establish a period beginning at a

date to be announced following the date of the order ap

proving this plan and ending thirty days thereafter as the

period in which written applications will be received for

transfers and reassignments from one school in the system

to the 12th grade of another school in the system for the

school year 1964-65, and will prepare and supply written

forms for that purpose together with a statement of the

rules of procedure applicable thereto. Said forms and

rules will set forth the information required to be fur

nished with such applications and the time within which

such apxjlications will be evaluated and either approved or

disapproved by the Superintendent. They will provide for

written notice of the Superintendent’s action and will in

form the applicant with respect to his or her rights to ad

ministrative review or appeal. All such applications will

35

Defendant Board’s Plan for Desegregation

be processed and acted upon without distinction based

solely on race. Pupils first entering the system in the 1964-

65 school year in the 12th grade in the system will be af

forded without distinction based solely on race the oppor

tunity to request original assignment to the school of their

choice in accordance with presently established procedure.

(5) The Board will establish a committee or group of

not less than six (6) or more than eight (8) members com

posed of principals or other teaching or administrative

personnel of the various schools in the system, to consist

of an equal number of white and Negro members, which

will be recognized as a recommendatory committee with

which the Superintendent of the school system or other

administrative personnel designated by the Superintendent

will discuss and consider proposals, suggestions, complaints

and other matters involving this plan. This committee will

fix and determine its own meeting dates, or it may be called

into meeting by the Superintendent, to consider and discuss

any matter it may consider advisable concerning this plan,

with authority to make recommendations to the Superin

tendent, and through him to the Board, but this authority

is not to supersede any other existing authority within the

system.

(6) This plan will be applied without distinction based

on race in all 12th grades in the system for the school year

1964-65. It will thereafter be similarly applied in all 11th

and 10th grades for 1965-66, all 9th grades for 1966-67, all

8th grades for 1967-68, all 7th grades for 1968-69, all 6th

and 5th grades for 1969-70, all 4th grades for 1970-71, all

3rd and 2nd grades for 1971-72, and all 1st grades for 1972-

73; being or becoming applicable without distinction based

36

Defendant Board’s Plan for Desegregation

on race for all grades in the system within nine school years

beginning with the year 1964-65.

By authority of the Board, this February 24, 1964.

B oard op P ublic E ducation and

Orphanage for B ibb County

By H. Gr. W eaver, President

37

O bjections to P lan o f B oard o f P ub lic

E ducation and O rphanage

[C aption Om itted ]

Come now, the plaintiffs in the above-styled action, and

file this their objection to the plan of defendant Board of

Public Education and Orphanage for Bibb County which

has been filed in this case and as grounds show:

1 .

Though paragraph 1 of the Plan vests the superintendent

with power to administrate the matter of the designation

of the respective public schools sought to be attended by

students of Bibb County, no criteria are enumerated by

which the superintendent is to be guided in making such

designation; nor is there any procedure set out governing

the appeals from the superintendent to the Board should

there be some dissatisfaction with the designation. Also,

there is no procedure enumerated by which one might

appeal from the action of the. Board to the State Depart

ment of Education.

2.

Paragraph 2 of the Plan is objected to for the reason

that:

(a) There has been no revision in “the identification of

residential areas or in the identification of the high school

to which pupils graduating from the several grammar

schools are assigned,” nor is there any suggestion that

any change might be effected in the near future;

(b) No basic plan is reasonably established for bringing

about a transition to a unitary non-racial system at anytime

in the immediate future.

38

Plaintiffs’ Objections to Board’s Desegregation Plan

3.

Paragraph 3 of the Plan mentions factors to be taken

in account by the superintendent in granting or refusing

to grant requests for re-assignment without spelling out

what those general factors are. Thus, the provisions of

said paragraph are so general as to have little meaning.

4.

The provisions of paragraph 4 appear to place the bur

den of initiating some change in the present system upon

those seeking transfers without the defendants themselves

initiating any real action in revising the present dual

system.

5.

The provisions of paragraph 5 of the Plan is too general

and establishes no time limitations on the proposed action

by the Board relative to recommendations, proposals and

suggestions from a committee or group referred to in said

paragraph. It is conceivable that such proposed action

could take many months and serve only to delay the prep

aration of an effective and reasonable plan.

6.

The provisions of paragraph 6 of the Plan purports to

permit eight years for the total desegregation of the Public

School System of Bibb County, whereas, it has been ten

years since the handing down of the 1964 Supreme Court

Decision concerning public school education. Thus, the

defendants’ proposal that some eighteen years after the

handing down of the decision as being a reasonable time for

the completion of desegregation of the public schools of

39

Plaintiffs’ Objections to Board’s Desegregation Plan

Bibb County is entirely inconsistent with reason or neces

sity, and is therefore objectionable.

7.

Because of the gross inadequacy of the Plan, and because

there are other more specific objections which plaintiffs

expect to make, it is respectfully requested that this Court

set a day and time certain for a hearing on these and other

objections which the plaintiffs may present.

W herefore , plaintiffs pray that this Court set a day

and time certain for a hearing on the objections filed.

This 16th day of March, 1964.

[Signatures and Certificate Omitted]

40

P lain tiffs’ P lan o f D esegregation

[C aption Om itted ]

The following plan for initiating desegregation of the

Bibb County, Georgia, public schools was prepared by

plaintiffs to provide this Court with a method of effectu

ating plaintiffs’ objections to the desegregation plan sub

mitted by the defendant Board of Education.

Preliminary Statement

It is the experience of plaintiffs’ counsel that the deseg

regation of public schools by grades according to uni-

racial zone lines, while perhaps ultimately necessary to a

truly desegregated system, does not, as administered dur

ing the initial years, achieve such desegregation:

1. White pupils, even when residing close to Negro

schools are, through one administrative procedure or an

other, not required to attend Negro schools.

2. Negro students within the grades being desegregated

are not required to attend white schools located in the

zones of their residence unless the Negro parents express

their desire for such assignments, and even then must fre

quently meet criteria, standards, and tests not applied to

white students assigned to such schools as a matter of

course.

3. The number of students desiring desegregated assign

ments during the initial years is generally small, and since

only those desiring such assignments receive them, there

is no justification for restricting such requests to only one

or two grades, or in any way limiting the right of such

applicants, including usually most of the plaintiffs, to

obtain assignments to desegregated schools.

For these reasons, plaintiffs respectfully submit that

the following plan will meet their objections to the Board’s

41

Plaintiffs’ Plan of Desegregation

plan and, more importantly, insure that desegregation is

initiated in the public schools of Bibb County during the

forthcoming 1964-65 school year in a manner acceptable to

plaintiffs and not disruptive to the operation of the schools.

Plaintiffs’ Plan Of Desegregation

By appropriate means, the parents of all students in

the public schools in Bibb County, Georgia, shall be notified

of their right to seek and obtain desegregated assignments

for the 1964-65 school year. The Board shall provide appli

cation forms for such assignments and provide a reason

able time in which the application forms shall be completed

and returned to the Board.

The application forms shall enable the parents to request

a first and second choice of schools, with the understanding

that if bona fide problems of school capacity or transpor

tation render inadvisable assignment to the school of the

first choice, the child shall be assigned to the school of the

second choice. Administrative problems of assignment may

be solved by the Board as long as all students requesting

desegregated assignment are granted same.

Students entering the public schools for the first time

shall have the right to seek and obtain desegregated assign

ment on a basis no different than that set forth above for

students presently in the system.

This plan does not prevent the Board from initiating, or

the plaintiffs from urging at appropriate times prior to

the beginning of subsequent school year's, the initiation of:

(1) general desegregated assignments according to uni-

racial zone lines; (2) faculty desegregation; or (3) other

measures required to bring about a completely desegre

gated system of schools in Bibb County.

[Signatures and Certificate Omitted]

42

T ran sc rip t o f H earing

[C aption Om itted ]

Non-jury before:

H onorable W. A. B ootle,

United States District Judge.

at Macon, Georgia,

April 13-14, 1964.

A p p e a r a n c e s :

For Plaintiffs:

H ollo w ell , W ard, M oore & A lexander,

859i/2 Hunter St. N. W.,

Atlanta, Ga. 30314

Mr. D onald L. H ollowell, of counsel.

For Defendants:

J ones, S parks, B enton & Cork,

1007 Persons Building,

Macon, Georgia.

M r . C. B axter J ones, of counsel.

Reported by Claude J oiner , J r., Official Reporter, U. S.

Court, Middle District of Georgia, P. 0. Box 94, Macon, Ga.

Macon, Georgia, April 13, 1964

9 :40 A.M.

The Court: Gentlemen, we have the case of Shirley

Bivins, et al. against The Board of Public Education of

Bibb County. I think the name was finally corrected in the

subsequent pleadings.

43

Issues Outlined

The letter to counsel stated that this hearing was for

the purpose of hearing objections and arguments of coun

sel with respect to the proposed plan. That language was

lifted from the pre-trial order. I take it that this is really

the final hearing in this case, insofar as a school ease ever

has a final hearing, as distinguished from preliminary

motions and applications for preliminary injunction, and

so forth?

Mr. Jones: I think that’s correct, Your Honor. Possibly

I might qualify that to this extent: Actually, this hearing

is set to consider the plan which has been submitted and

objections thereto, and evidence and arguments pertaining

to the plan itself.

It so happens that there is a minimum of dispute be

tween the parties as to the facts on which the complaint

was based. Your Honor may recall, or I ’m not certain

that you’ve, had the opportunity to read the pleadings at

all, but you may recall that the Defendant Board of Edu

cation admitted that it had, up until this time, been oper

ating a segregated school system.

Furthermore, the Defendant Board admitted that the

Plaintiffs as representative of the class were entitled to

relief by reason of that fact.

Therefore, I assume that what we’re now doing is pre

senting evidence which bears upon the plan, and not evi

dence essentially which bears upon any controversy that

may have existed between the parties, absent admissions

and general agreement between the parties as to the facts

on which the complaint is based; and in that posture, I ’m

also assuming that the Board is the moving party at this

hearing and we will proceed on that basis, unless there

is some question raised as to it.

44

Burden of Proof

The Court: Mr. Hollowell, do you have any objection

to the Board being the moving party?

Mr. Hollowell: May it please the Court, it just seems

somewhat an anomaly to me that the Board would be the

moving party, inasmuch it is my understanding that this

is a hearing for the purpose of making objections to the

plan, as it has been submitted. I would rather think that

it would be the other way around.

The Board has done that which the Court directed in

its order, insofar as it has brought in a plan. That is not

to say that we would go along with the idea that they have

done what the Court directed from the standpoint of the

compass of the plan. I think it would be just the reverse,

as I see it, sir.

Insofar as the other matters are concerned—I said “com

pass” but I meant “scope” of the plan—insofar as the

other matters are concerned, I think I agree with counsel

that the basic essentials from the standpoint of the suit

itself have been admitted; so, that there is nothing that I

see that would need to be submitted, unless it relates to the

basis for the plan or something that is referred to in the

plan which might call for evidence of a contrary nature,

in order to set out effectively what our contentions are;

but, other than that, sir, I most certainly agree.

Mr. Jones: May I add to my remarks ?

The Court: Yes sir.

Mr. Jones: In the first place, Your Honor, I think a

more orderly presentation of this case can be made by the

Board proceeding. That is my first premise.

Secondly, if we accept the position that we now have

presented a plan and that the question is upon the approval

of that plan, then it’s no different from any other proceed

ing in which a propounder of a will finds himself with

45

Burden of Proof

caveators objecting to it, or a plaintiff in an ordinary case

finds himself with the defendant objecting to it.

I do not think that this hearing is on the objections. I

think the hearing is on the plan and, while, of course, I ’m

subject to the Court’s direction, I still think it would be

proper and more effective procedure for the Board to

proceed in the first instance.

The Court: Well, as a matter of fact, the areas of dis

agreement, as you gentlemen have indicated, have been

narrowed considerably; so, that we have left, not the ques

tion of whether the Plaintiffs are entitled to relief, but to

how much relief, and to what relief. That results from the

admissions which have been made.

The Defendant was ordered to present a plan; such plan

has been presented. The pre-trial order provided that then,

if there were objections, a hearing would be had upon those

objections with such evidence as might be heard.

I don’t know that it makes a great deal of difference who

assumes the burden of proof but, if the Plaintiffs want it,

I think I ’ll let them have it.

Mr. Hollowell: May it please the Court, I think the

preliminary remarks which I might have made have already

been made for the record dealing with the matter of the

plan itself.

The Court: Now, let me make this suggestion for the

information of counsel: The question, in addition to what—

well, included in the question of what relief the Plaintiffs

are entitled to, includes the question of an injunction, if

an injunction is necessary.

Mr. Hollowell: Bight.

The Court: So, I take it that is before the Court at this

time?

Mr. Hollowell: Yes sir.

46

Objections to Plan

The Court: Very well.

Mr. Hollowell: May it please the Court, in the Court’s

pre-trial order a portion of the prayer of the Plaintiffs was

a recital. Therein there was a request that this Board be

enjoined from continuing to operate a dual school system in