Notice of Depositions of Armor and Calvert; Findings and Orders of the Court

Public Court Documents

June 18, 1992

12 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Notice of Depositions of Armor and Calvert; Findings and Orders of the Court, 1992. 61c19dcb-a346-f011-8779-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4081e076-1eca-4965-82a5-6f973e0949d6/notice-of-depositions-of-armor-and-calvert-findings-and-orders-of-the-court. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

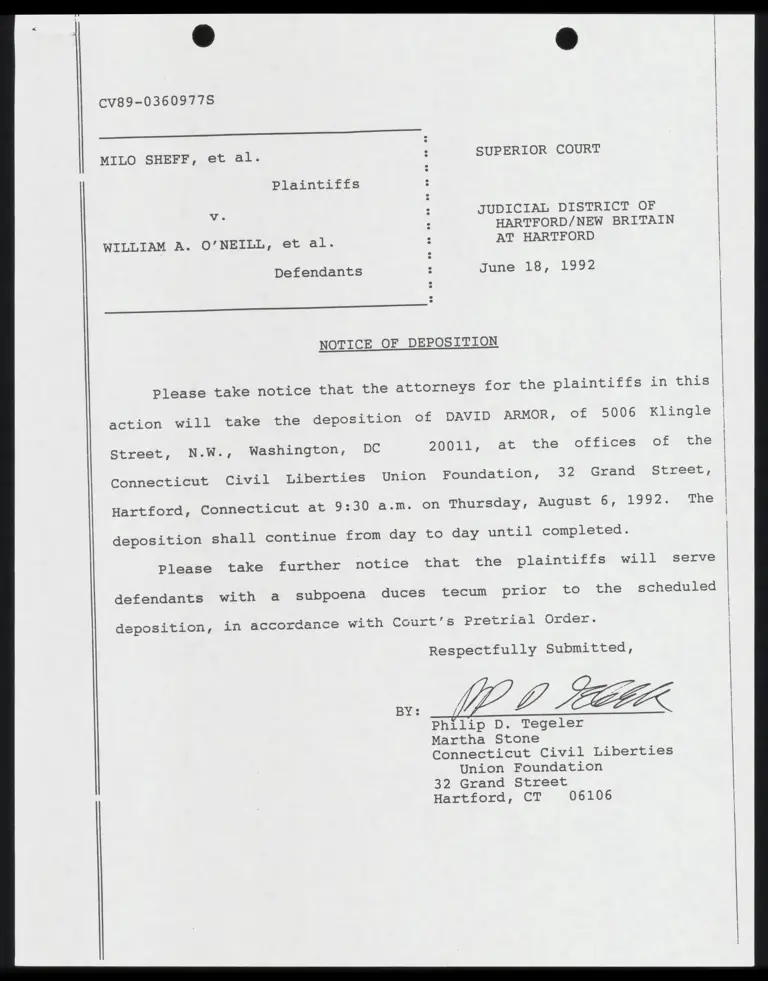

cvg9-03609775

MILO SHEFF, et al. SUPERIOR COURT

Plaintiffs

JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF

HARTFORD/NEW BRITAIN

AT HARTFORD

Ve.

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, et al.

Defendants June :18, 1992

NOTICE OF DEPOSITION

please take notice that the attorneys for the plaintiffs in this

action will take the deposition of DAVID ARMOR, of 5006 Klingle

Street, N.W., washington, DC 20011, .at the offices of the

Connecticut Civil Liberties Union Foundation, 32 Grand Street,

Hartford, Connecticut at 9:30 a.m. on Thursday, August 6, 1992. The

deposition shall continue from day to day until completed.

please take further notice that the plaintiffs will serve

defendants with a subpoena duces tecum prior to the scheduled

deposition, in accordance with Court's Pretrial Order.

Respectfully Submitted,

Philip D. Tegeler

Martha Stone

Connecticut Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

32 Grand Street

Hartford, CT 06106

Wesley W. Horton

Moller, Horton, & Rice

90 Gillett Street

Bartford, CT 06105

Julius L. Chambers

Marianne Engelmann Lado

Ronald L. Ellis

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

Helen Hershkoff

John A. Powell

Adam S. Cohen

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

Wilfred Rodriguez

Hispanic Advocacy Project

Neighborhood Legal Services

1229 Albany Avenue

Bartford, CT 06112

John Brittain

University of Connecticut

School of Law

65 Elizabeth Street

Hartford, CT 06105

Ruben Franco

Jenny Rivera

Puerto Rican Legal Defense

and Education Fund

99 Hudson Street

132 west 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

New York, NY 10013

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

|

This is to certify that one copy of the foregoing has been mailed

{

postage prepaid by certified mail to John R. Whelan, Assistant |

Attorney General, MacKenzie Hall, 110 Sherman Street, Hartford, CT

be /l

06105 this /5% “day of June, 1992.

WL Fez,

Philip D. Tegeler

-@-

Cv-89 360977 S

MILO SHEFF, ET. AL.

VS.

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, ET. AL.

FINDINGS AND ORDERS OF THE COURT

C2

SUPERIOR COURT

HARTFORD/NEW BRITAIN

AT HARTFORD

JUNE 18, 1992

BEFORE: HONORABLE HARRY HAMMER, JUDGE

APPEARANCES:

PHILIP TEGELER, ESQ.

COUNSELF FOR THE PLAINTIFFS

JOHN R. WHELON, ESQ.

ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

William H. Juall

Court Monitor

° >-@

THE COURT: I want to identify the case

for the record. This is Docket CV-89 0360977,

Milo Sheff, et. al, v. William A. O'Neill.

The Court is being asked to rule on the defen-

dant's motion for order of compliance, which

is dated May 14, 1992. The Court would note

that the Court's ruling on the defendant's

motion for an order of compliance as to inter-

rogatories one through sixteen, as well as,

I believe, interrogatory nineteen, is based upon what the Court perceives to be the essential

role of pre-trial discovery in a case such

as this one, in which the plaintiffs are

seeking a declaratory ruling by the Court

on the issue of whether or not their rights

under the State Constitution are being denied.

I would point out that the ruling cannot

be made in a vacuum, it has to be based upon

the peculiar nature of this case, and reliance

upon precedent is not necessarily determinative.

The Court's ruling must necessarily be made in the light of what the law of this case,

so called, is at the present time, as it

has been explicated by the Court in its rulings

on the defendant's motions to strike, which

was decided on May 18, 1990. And its rulings

on their motion for summary judgement, which

@- —

was filed in February 24 of this year, February

24, 1992. As well as the Court's understanding

of the plaintiff's claims of law as they

have been articulated repeatedly in their

written and oral arguments in opposition

to those motions, and as they are set forth

in their pleadings.

The Court's review of the wording of

interrogatories one through seven, which

are captioned -- one through four, I believe,

are captioned, affirmative acts, five through

seven are captioned, failure to act. The

Court's review of those interrogatories is

that they're essentially contention interrog-

atories, in the sense that requests the facts

upon which the plaintiff based their legal

contentions. The Court accepts the plaintiff's

replies to those interrogatories as responsive

based on the plaintiff's consistent contention

throughout these proceedings, which is reasserted

in this amended response to those interro-

gatories that -- quote -- it is the present

condition of racial and economic segregation

in the region's schools that violates the

Connecticut Constitution as a matter of law

-- close quotes -- and that the State has

Ngo an affirmative duty under the Constitution

* ry

to provide -- as argued by the plaintiffs

-- to provide equal educational opportunity

for all its students.

The Court, however, will direct the

plaintiffs, in any event, to provide supple-

mentation to the extent necessary with respect

to one through seven. I wanted to ask you

specifically if you would, Mr. Tegeler, why

you felt that supplementation as to questions

five through seven was necessary. What was the basis for that contention as opposed

to one through four? Do you follow me?

MR. TEGELER: Your Honor, I think -

- I believe what we said in our brief and ;

in oral argument was that we have responded

fully. There are a couple items which have

come to our attention. For example, recommen-

dations made to the State, that weren't listed

in our response.

THE COURT: Well, what I'm indicating

to you, Mr. Tegeler, is that there is --

to the extent -- and I would suggest that,

all other things being equal, you disclose

rather than not. Because it's certainly

not going to do any harm. I'm indicating

to you, to the extent -- I'm indicating for

informational purchases and based on your

@- ~@

continued duty to disclose, if you think

that -- if there's any information in your

files which may be of assistance to the State

in discovery of further evidence, that you

should make those supplementations no later

than August 15, 1992.

MR. TEGELER: I believe there are such

documents, and we will comply, Your Honor.

THE COURT: The Court also finds that

interlocutories eight through ten as well

as five through seven, in part at least,

improperly and prematurely seek to have the

plaintiffs disclose what may essentially

be either a judicial determination, after

the constitutional question has been resolved,

or a judicially directed legislative determina-

tion, which so often happens if the decision

is in favor of the plaintiff, after the con-

stitutional issue has been resolved. And

in that connection I would just cite, in

addition to our own case, our Horton v. Meskill

case, we also have reference of Abbot wv.

Burke -- that is Abbot v. Burke, two, at

575 : Atlantic Second : 359 -- 371, there's

a reference to Chief Justice Hughes' concurring

opinion, in which he makes reference to the

importance of deference to the legislative

F

p

| S

—

—

—

eo -:- @ or

determination when a judicial determination

of unconstitutionality is made.

The Court concurs with the defendant's

argument that questions eleven through twelve

-- eleven and twelve, with regard to minimally

adequate education, and thirteen to fourteen,

the disparities in educational inputs and

outputs, based upon the law of the cases,

I have indicated are separate and distinct,

and the plaintiffs must frame their responses

accordingly, without incorporating their

responses to one set of questions by reference

to the other.

As to interrogatories fifteen and sixteen,

as well as nineteen, the Court will direct

that full and up to date supplemental responses

be filed by the plaintiffs no later than

August 15, 1992. Insofar as interrogatory

eighteen in concerned, with regard to expert

witnesses, the Court finds that the plaintiffs

are in compliance. And of course, Mr. Whelon,

the Court's rulings are without prejudice

to your filing an appropriate motion after

August 15.

I wanted to indicate to you gentlemen

that I would like to ask you at this point

what -- I believe you feel at least a --

% -1- @

there should be a conference in chambers,

a status conference in chambers. Do you

agree, gentlemen?

MR. WHELON: After August 15, yes.

THE COURT: I'll be happy to oblige

you at this point. So I'll ask you to meet

with me in chambers right after the recess.

MR. WHELON: Your Honor, may an objection

and exception be foted to your ruling, tneofdr

as you've denied portions of the defendant's

motion?

THE COURT: I certainly will.

MR. WHELON: Thank you, Your Honor.

THE COURT: You may have a comparable

exception to the extent that the ruling was

against you. MR. TEGELER: Thank you, Your Honor. THE COURT: We'll stand in recess.

$ -s-@

Cv-89 360977 S

MILO SHEFF, ET. AL.

VS.

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, ET. AL.

CERTIFICATION

I, William H. Juall, do hereby certify that - the -

foregoing is a true and accurate transcription of the

tape in the above-captioned matter, heard before the

Honorable Harry Hammer, Judge of the Superior Court

of the Hartford/New Britain J.D. on June 18, 1992, in

Hartford, Connecticut.

Dated this day of June 19, 1992, in Hartford,

Connecticut.

ars AN

William H. Juall

Court Monitor

*

Wp

Cv89-0360977S

MILO SHEFF, et al. SUPERIOR COURT

Plaintiffs

v7. : JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF

HARTFORD/NEW BRITAIN

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, et al. AT HARTFORD

‘

a

e

e

LL

]

L

L

Defendants June 16, 1992

NOTICE OF DEPOSITION

Please take notice that pursuant to Rule 30 of the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure the attorneys for the plaintiff class in this

action will take the deposition of LLOYD CALVERT, c/o Office of the

Attorney General, MacKenzie Hall, 110 Sherman Street, Hartford, CT

06105 at the offices of the Connecticut Civil Liberties Union

Foundation, 32 Grand Street, Hartford, Connecticut, at 9:30 a.m. on

Tuesday, September 8, 1992. The deposition shall continue from day

to day until completed.

Please take further notice that the plaintiffs will serve

defendants with a subpoena duces tecum prior to the scheduled

deposition, in accordance with Court’s Pretrial Order.

Respectfully Submitted,

BY: V/A / ZZ ad

rr

Philip D. Tegeler

Martha Stone

Connecticut Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

32 Grand Street

Hartford, CT 06106

rh |

Wesley W. Horton Wilfred Rodriguez

Moller, Horton, & Rice Hispanic Advocacy Project

90 Gillett Street Neighborhood Legal Services

Hartford, CT 06105 1229 Albany Avenue

Hartford, CT 06112

Julius L. Chambers John Brittain

Marianne Engelman Lado University of Connecticut

Ronald L. Ellis School of Law |

NAACP Legal Defense & 65 Elizabeth Street

Educational Fund, Inc. Hartford, CT 06105

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

Helen Hershkoff Ruben Franco

John A. Powell Jenny Rivera

Adam S. Cohen Puerto Rican Legal Defense |

American Civil Liberties and Education Fund

Union Foundation 99 Hudson Street |

132 West 43rd Street New York, NY 10013 |

New York, NY 10036

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that one copy of the foregoing has been mailed

postage prepaid by certified mail to John R. Whelan, Assistant

Attorney General, MacKenzie Hall, 110 Sherman Street, Hartford, CT

JZ

06105 this /7 "day of June, 1992.

Wp Sze

Philip D. Tegeler