Grigsby v. North Mississippi Medical Center Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Grigsby v. North Mississippi Medical Center Appellants' Brief, 1976. 6046bacb-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4086b714-f523-4429-aa66-1d5409bc3ff2/grigsby-v-north-mississippi-medical-center-appellants-brief. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

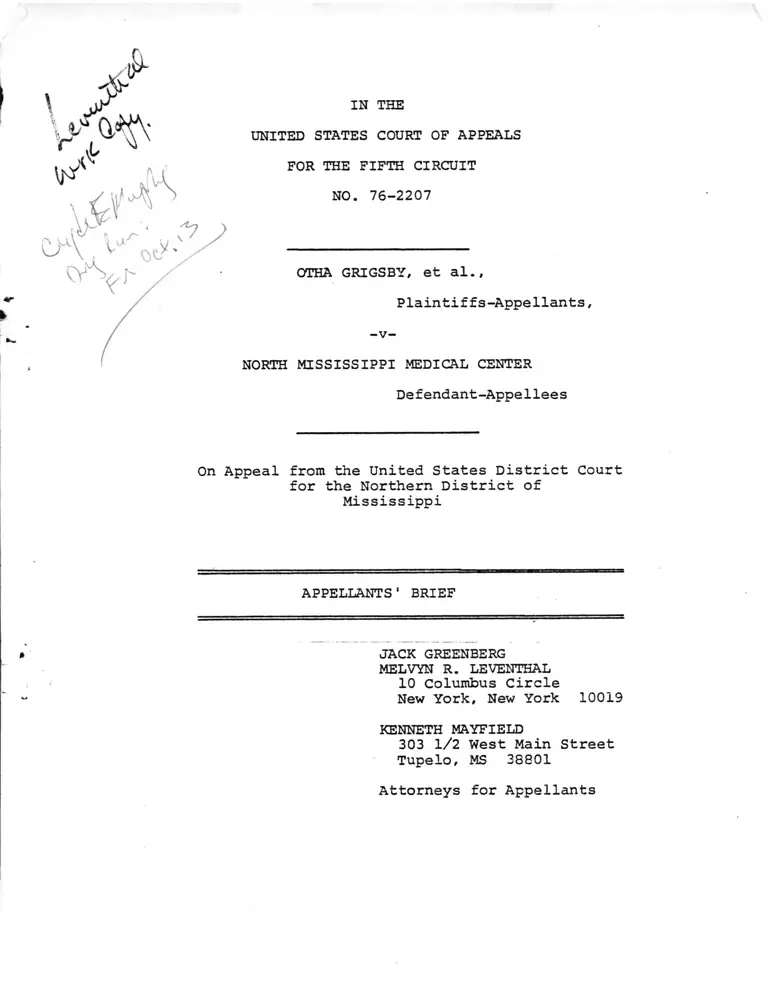

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 76-2207

OTHA GRIGSBY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

-v-

NORTH MISSISSIPPI MEDICAL CENTER

Defendant-Appellees

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of

Mississippi

APPELLANTS' BRIEF

JACK GREENBERG

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

KENNETH MAYFIELD

303 1/2 West Main Street

Tupelo, MS 38801

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTSi

1

-.i.1

.11■M:j

Page

Table of Cases...................................... i

Rule 13 Certificate............................... 2

Statement of the C a s e ............................. 4

Statement of the Facts . . . . . ................... 7

1. G e n e r a l ............................. 7

2. Statistical and Other Evidence

of Employment Discrimination ......... 8

3. Statistical Evidence Relating

to Racially Discriminatory

Discharges........................... 13

4. Named Plaintiffs ..................... 14

\

Argument .......................................... 21

Conclusion.......................................... 31

Exhibit A .......................................... 32

Exhibit B .......................................... 34

TABLE OF CASES

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975)................................. 27

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Ref. Corp.,

495 F.2d 437 (5th Cir. 1974)....................... 25

Brown V. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co.,

457 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972)....................... 25

Burns v. Thiokol Chemical Corp.,

483 F.2d 300 (5th Cir. 1973)....................... 30

East v. Romine Inc.,

518 *F.2d 332 (5th Cir. 1975)....................... 27

Local 189, United Paperwork v. U.S.,

416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969)....................... 27

Rodriguez v. East Texas Motor Freight,

505 F .2d 40 (5th Cir. 1974)......................... 29

Rowe v. General Motors

457 F .2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972)....................... 25

Sagers v. Yellow Freight Systems, Inc.,

529 F .2d 721 (5th Cir. 1976)....................... 21

United States v. Hayes International,

456 F.2d 112 (5th Cir. 1972)....................... 21

United States v. N.L. Industries, Inc.,

479 F .2d 354 (8th Cir. 1973)....................... 25

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co.,

530 F.2d 1159 (5th Cir. 1976) ..................... 25

- i -

IN THE

■i

j

i

-i

I ’ \

]

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 76-2207

OTHA GRIGSBY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

-v-

NORTH MISSISSIPPI MEDICAL CENTER

Defendant-Appellees

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY LOCAL RULE 13 (a)

The undersigned counsel for plaintiffs-appellants

Otha Grigsby, et al., in conformance with local Rule 13(a),

certifies that the following listed parties have an interest in

the outcome of this case. These representations are made in order

that judges of this Court may evaluate possible disqualification

or recusal:

1. Otha Grigsby, Eddie Black, and Essie Sneed, named

plaintiffs and intervenors.

2. The class of present, past or future black

employees of the North Mississippi Medical Center, Inc.

represented by named plaintiffs.

2

|\»»~| .VV

3. The North Mississippi Medical Center, Inc.,

defendant.

- 3 -

!rr-" ” ’TfrTi-y-;

r

1'•-i•4I;4.4r

IN TH E

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 76-2207

OTHA GRIGSBY, et al.,

P iaintiffs-AppeIlants,

-v-

NORTH MISSISSIPPI MEDICAL CENTER

Defendant-Appe1lees

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of

Mississippi

APPELLANTS' BRIEF

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

I

On August 20, 1974, plaintiff Otha Grigsby filed a

complaint as a class action against the North Mississippi Medical

Center (hereinafter called the "Medical Center") in Tupelo,

Mississippi charging racial discrimination in employment in

violation of 42 U.S.C. 1981. Plaintiff charged individually that

- 4 -

<

he was terminated because of his race. (O.R. 1)

January 14-, 1975, the District Court entered an Order

granting plaintiffs' October 29, 1974 motion for leave to add

plaintiffs-intervenors and to amend his Complaint (O.R. 52, 65).

Specifically, Betty Sullivan intervened alleging that she had

been harassed by defendant because of her race and Eular Young

intervened alleging that she had been constructively discharged

because of race. May 12, 1975, the District Court entered an

Order granting plaintiffs' February 27, 1975 motion for leave to

add plaintiffs-intervenors and to amend Complaint a second time.

(O.R. 94, 97) This time, Eddie Black, Doris Collier, and Essie

Sneed intervened alleging that they were, either actually or

constructively, discharged by defendant because of race; in

addition, Eddie Black alleged that he had been denied a promotion

because of race. Intervenor Black had filed a complaint of

discrimination with the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission

(which resulted in a finding of discrimination), had received a

"Right to Sue" letter and, accordingly, jurisdiction then vested

in the district court under 42 U.S.C. §2000e, et seq.

January 12, 1976, plaintiffs filed a Motion for Class

Action Certification. (O.R. 108) The motion was referred to the

U.S. Magistrate for a report and recommendations. On February 11,

1976, the magistrate filed his report and recommended that a class

action, defined as follows, be approved:

- 5

i.iuij: -

‘T T T r-T-rr-rec

i

Ju

uS

kU

k̂

ĵ

ik

l̂

im̂

LU

h'„̂

iiL

V».

.».

.l

it i

M.

.^

L

.u

^

.

.

*,

.

. jMii-»̂i.M»r̂r-fe*yfcâ ^̂jr;ai‘î-»iii.JT«,tii~A.ftf̂aat'TTMi&̂aiaiiiitfla>fcTii -Mfat-'.iii!tai<a»̂ĵ. , -A. r\jMr̂>TTfW«'. n,î -̂j-J..1, -.*.-r. .

1

. ■»

"&11 present, discharged, laid off, and future

black employees of defendant who have been or may in

the future be affected by any policy or practice of

defendant of racial discrimination in the areas of

initial job assignment, promotions, job classification,

employee disciplinary actions and termination of

employment." (O.R. 114)

February 23, 1976, the Court entered an Order

certifying the case as a class action, exactly as suggested by

the magistrate. (O.R. 146)

Plaintiffs filed three sets of interrogatories. The

second set sought to discover information relating to all of

defendant's complexes, units, divisions and departments. (O.R. 31)

The defendant filed a motion for a protective order and refused

to answer most of the interrogatories. (O.R. 54) January 24, 1976,

after a hearing, the District Court granted defendant's motion

for a protective order and required the plaintiffs to submit a

third set of interrogatories relating only to post hiring employment

practices at the Mental Health Complex and at the Baldwyn Satellite

Unit, two divisions of the hospital only employing approximately

100 persons. (O.R. 84)

Prior to trial Doris Collier moved to be dismissed

and was dismissed as a plaintiff. Betty Sullivan was dismissed

from the employment of defendant shortly before trial, m s . Sullivan

i

moved for leave to amend her complaint to include her dismissal

and after that was denied by the Court, she withdrew her original

complaint. (O.R. 147)

- 6 -

The case was tried on the claims of Otha Grigsby,

Eular Young, Essie Sneed and Eddie Black and the defined class

on February 23, 1976. February 27, 1976, after four days of

trial, the District Court made a bench ruling (Tr. Tr. 895-916)

and entered its Final Judgment for defendant on all issues.

(O.R. 149)

A notice of Appeal and Motion to Proceed in Forma

Pauperis was filed by plaintiffs March 26, 1976 (O.R. 151, 153)

and granted by the District Court on April 26, 1976. (O.R. 163)

Plaintiff intervenor Eular Young on October 20, 1976, filed a

Motion to dismiss her appeal. This appeal, then is advanced by

Otha Grigsby, Essie Sneed, Eddie Black and the defined class of

blacks.

- 6a -

Statement of Facts

General

The defendajit-appellee, North Mississippi Medical

Center, Inc.^ operates three interdependent health facilities:

(a) a 467 bed hospital in Tupelo which has between 18-20 different

departments (e.g. housekeeping, dietary, nursing); (b) a separate

50 bed "satellite unit," itself a small hospital. *in Baldwyn;

(c) a Mental Health Complex,, physically located within the *

MjJJU

hospital in Tupelo but operating a mental health program in a

ten county area. (O.R. 116, T.Tr. 15-16) Defendant employs

a hospital administrator who is responsible for all three facets.

Authority for all relevant employment decisions, at the Baldwyn

unit and the Mental Health Complex, lies in department heads who

report to and work for superior department heads operating in the

main hospital facility. (T. Tr. 17-18) Thre are no standards of

any kind controlling any supervisor in his or her hiring, promotion

and dismissal decisions. (T. Tr. 17, 20, 37, Ans. to Interrogatories,

40-41) Each department head is, and always has been, white. . In

addition to the department heads the Medical Center has between

six and nine other persons in general administrative positions at

the Medical Center all of whom are and always have been white.

(Exh. 135-138) No black employee has ever supervised any white

employee in defendant's entire history. (P.Exh.64, Interrogatory 43).

- 7 -

The satellite unit and mental health complex employ

approximately 100 persons, 27 percent of whom are black. As of

November 30, 1975, defendant had a total of 1,120 employees,

814 (73%) of whom were white and 306 (27%) of whom were black.

The Medical Center is located in an area that is 21 percent

1/

black. (Tr.Tr. 93)

Statistical and Other Evidence of

Employment Discrimination

The Medical Center's work force can be conveniently

divided into five (5) categories: (1) officials and managers;

(2) professionals; (3) housekeeping; (4) dietary; and (5)

business office and clerical personnel.

At the Mental Health Complex and Baldwyn Satellite Unit

the above categories are and have been, with few exceptions for

the last five years, one hundred percent (100%) either black or

2/

white (Exhibit "A" hereto) All professional employees (excluding

nurses) are and have been white, with the exception of Otha Grigsby

1/ During discovery plaintiffs attempted to discover

information from the Medical Center relative to its employment

practices in all of its departments over a 15 year period.

However, the District Court, on Motion of the Medical Center for

a Protective Order, ruled that plaintiffs could discover only

employment practices relative to the Mental Health Complex and

the Baldwyn Satellite Unit — the units where then named plaintiffs,

Otha Grigsby, Betty Sullivan, and Eular Young were either employed

or had been employed. Moreover, discovery was limited to the

post-hiring practices of the Medical Center after January 1, 1970.

(Tr.Tr.84) Most of the statistical data presented by plaintiffs

therefore relates directly to the Mental Health Complex and Baldwyn

Satellite Unit and only by inference to the remainder of the

Medical Center.

2/ see on the following page

- 8 -

(the lead plaintiff), and three other blacks who were at best,

"paraprofessionals" holding positions which do not require any

training or even a high school diploma (O.R.323). Moreover,

the "paraprofessionals" were hired as a part of a specially

funded alcoholism program which has been discontinued; and

currently there are no black professionals or "paraprofessionals."

(O.R.31D-2/

In housekeeping, one of the least desirable and lowest

paid categories, defendant, from January 1, 1971 to May of 1974,

employed seven or eight blacks and no whites. (Exhibit "A" hereto)

On May 27, 1974, a white (Polly Nelson) was transferred from the

dietary department to housekeeping and (O.R.696) immediately made

supervisor over all the blacks in the department. Ms. Nelson has

only a ninth (9th) grade education, (O.R.697) has been employed

by the defendant since February 2, 1970 (P. Exh., 64, p,12e) and

has never worked in the housekeeping department. (O.R.695)

Compare Ms. Nelson's qualifications to those of blacks; Irene

Copeland has an eleventh (11th) grade education, has been employed

by the defendant since July 28, 1969, and has always worked in the

housekeeping department. (P. Exh. 64, p.l2m); Annie Richardson

has been employed by the defendant since May 1, 1967, has always

been employed in the housekeeping department and had an eight (8th)

grade education? (P. Exh. 64, p.l2p) Helen Beene has been employed

2/ The only category on which plaintiffs have data

covering the entire Medical Center (see f.n.l above) is officials

and managers. No black has ever been so employed at the Medical

Center although up to 59 whites have been so employed at a given

time. (P. Exh.135)

3/ In January, 1975, there were 19 persons employed as professionals or "paraprofessionals," 2 persons (10%) of whom were black.

- 9 -

by the defendant since February 3, 1968, has always worked in

the housekeeping department and has an eight (8th) grade education.

(P. Exh. 64, p.l2m) Indeed, Ms. Nelson testified that Ms. Beene

supervises in her absence:

Helen Beene has been with the Medical Center for

nine years and on the days that I am off she

relieves me. If anything comes up Helen is in charge

to see that things are done. (Testimony of Ms. Nelson,

O.R.708)

The defendant offered no explanation for its failure to

promote any of the named black employees to the supervisory

position nor did it explain why the housekeeping department has

remained all black for at least the last five years, except for

the white supervisor. The following is an excerpt taken from the

testimony of the hospital administrator (Dan Wilford):

BY THE COURT:

Q. I think his question was if you had

an explanation as to why during all

these years, '71, '12, '12, '74 and

'75 all the people that worked in

the housekeeping department were black,

with the exception of this one supervisor.

A. No sir, I have no explanation (O.R.29)

On January 1, 1971, eleven (11) persons were employed in

the dietary department, eight (73%) of whom were white. From

January, 1972 to May, 1974 there were ten persons who were working

in the dietary department, seven (70%) of whom were black. From

May, 1974 up to the date of trial there were nine persons working

10

in the dietary department, seven (78%) of whom were black.

(Exhibit "A" hereto). Of the three whites employed, one

(Ozelle McCarthy) is head supervisor, Nora Lovell is an assistant

supervisor (O.R.34) and the thrid white (Polly Nelson) was promoted

to supervisor after working for the defendant on a part time

basis for only two months. (O.R.696) The white supervisors are

no more qualified than the blacks whom they supervise. The head

supervisor has an 11th grade education and has been employed by

the defendants since May of 1969. Ms. Lovell has a grade school

education and has been employed by the Medical Center since

May 29, 1969, and Ms. Nelson, as noted above, has a ninth (9th)

grade education, and has been employed by the defendant since

February of 1970. (O.R.696) Again, compare these whites to black

employees: Rosi Mae Richardson, whose educational background is

unknown, has been employed by the defendant since October of 1967

(P. Exh. 64, p,12m) Ms Richardson was used by defendant to instruct

Ms. Nelson in her responsibilities; coincidental to Ms. Nelson's

promotion Ms. Richardson was made a "first line supervisor," (the

first black to hold that position in defendant's history) but she

still occupies a position inferior to that of Ms. Nelson; (Tr.Tr.

710-714) Rosie Lee Richardson has a ninth grade education and

has been employed in the dietary department since September of

1968 ; (p. Exh. 64, p.l2m) Eulene Scales has a 12th grade education

and has been employed in the dietary department since July of 1969.

(P. Exh. 64, p.l2m) The testimony of the hospital administrator

is representative of the explanation offerred by defendant for

this discriminatory pattern:

- 11 -

■i

.:

a

.-.

u.v

a?r

jx

u

n

,ii

-■

»v>

. u

—

.,

■ •' -- -

Q. Do you have any explanation as to why

from 1971 to 1975 the only whites that

you had in the dietary department were

supervisors or assistant supervisors?

A. No sir.

Q. Do you have any explanation as to why

all of the workers in those departments

from 1971 to 1975 were blacks?

A. No sir. I assume that those were the

jobs that they applied for or they were

placed in after making application for

employment. (O.R.39, 40)

In January, 1971 and 1972 there were 11 persons employed

in the business office and as clerical personnel none of whom was

black. (Exhibit "A" hereto) In January, 1973, a black woman was

employed but only under the same specially funded alcoholic program

as the "paraprofessionals" referred to above. In addition, she

was not working at the main unit or even at a branch unit of the

hospital? rather she worked at the New Life Center, a walk-in

center for alcoholics located in the black neighborhood in Tupelo.

(Tr. Tr.469) In January, 1974, no black was employed as secretary.

In January, 1975, there were 17 persons listed in the category of

business office and clerical personnel, one of whom was black.

(Exhibit "A" hereto) But she was employed after this lawsuit was

filed and replaced another black that had been employed a few months

earlier during an EEOC investigation into defendant's practices.

(Exh.64, p.35x)

Turning to job classifications, the Medical Center admits

that 14 are, and for the last five years have been, occupied solely

by whites. The classifications are: (1) Registered Nurse, (2) Head

Supervisor, (3) Supervisor-Housekeeping, (4) Business Office Personnel,

(5) Maintenance worker, (6) Medical Technologist, (7) Radiological

12

T■i'I

Technologist, (8) Psychiatric Social Worker, (9) Recreational

• ]

Therapist, (10) Recreational Assistant, (11) Social Worker, (12)

Coordinator-counselor, (13) Therapist and (14) Mental Health Worker.

(P.Exh. 64, Interrogatory 13)

amJ-i "• ;ili»i•«:''̂ L*.rTr4V>,ih ■ »~*Kfcr ~ i «Vi-V*C» « .** -•_■■ ■■«-»-., » _ T.— * \ -. .^u. .- ......r ■ -1 • j---__i. ̂JLi "-.v - , , - ,: ■ ; -- - - »■ - ,____ w i»-:. V.H

i

1' A1

.11\i

j

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission investigated

a charge of racial discrimination filed by Eddie Black individually

and on behalf of a class of black employees segregated to the lower

job classifications. The EEOC found on the basis on the records at

the Medical Center that there was probable cause to believe that the

jobs were segregated according to race. The following excerpt is

•j taken from the determination:J,.J

"While only four persons at the Mental Health Complex

serve in the capacities of Director, Supervisor, or

Manager, and all are white, the North Mississippi Medical ■j Center, as of April 26, 1974, employs 26 officials and

Managers and all are white. While 161, or 75 percent of

.] its black employees are employed in the lowest category,

j that of service worker, only 221, or 31 percent, of its

white employees are employed in this category." (P.Exh.90)

The Medical Center has absolutely no explanatory evidence to rebut

those statistics.

STATISTICAL EVIDENCE RELATING TO

V RACIALLY DISCRIMINATORY DISCHARGES

Whereas, the black employees at the hospital comprise

only 27 percent, the percentage of blacks discharged for cause is

44 percent. No evidence was presented by the hospital to explain

why the discharge for cause rate for black employees is 17 percent

higher than the percentage of blacks employed by the hospital.

The following excerpt is taken from Mr. Wright's (the Personnel

Manager) testimony:

- 13 -

•IT - 3? V" >-■

•>. vi. ~ • ■ ^ ■ ■ n / . . r v ; . r ^ ' »-■ ••• - ---- :. ■•.rr v- - -•■— - — -.---- >,-•. - - i.

-I

)]

3

ii

■1 •j

• \

Q. How do you explain the fact that 27 percent of

your employees are black and yet 44 percent of

those dismissed for cause are black? That is

about a 17 percent differential.

A. I don't know that I can realistically tell you

the reason why. I guess my off-the-head comment

would be that people who are terminated for

cause are newer employees, probably in less

highly skilled areas, prone to terminate because

of the type of work that is being done. It is

a more transient group of employees, I would

imagine. (O.R.836)

NAMED PLAINTIFFS

Otha Grigsby, the lead plaintiff, holds a B.S. Degree

from Alcorn A&M University and a M.S., from the University of

Mississippi. (O.R.534) He was employed by the Medical Center

in the Mental Health Complex as an Occupational Health Special

ist on August 23, 1973 (P.Exh.64, p.120). Before being em

ployed by the Medical Center, Grigsby had years of experience

in industry at both the production and supervisory levels.

(O.R.552) He was terminated one year after being employed, in

August, 1974, by Duncan Clark, the Director of the Mental Health

Complex (P.ExH.31)

I-1j

Grigshy was the first and last truly professional black

to be employed by the Medical Center in the Mental Health Com

plex or Baldwyn Satellite Unit. He was hired as part of a

specially funded Mississippi Occupational Health Program,

established to assist employers with troubled employees, e.g.,

those with alcohol problems, and administered through Mental

Health Complexes throughout the State; the Mental Health Com

plex of the defendant Medical Center was responsible for the

program in Lee and ten surrounding counties. Grigsby's

14

r tn r t^ H i’a * - '-' ’ ■

--

responsibility was to solicit participation in the program.

(Tr. Tr. 16, 356, 357)

Grigsby's initial tasks included compiling information

on the various industries and businesses in his 11 county area,

preparing an Industrial Health Program, and obtaining signed

contracts from businesses confirming their participation in

the program. (O.R. 536)

It took Grigsby approximately two months to gather

statistical and other data on the businesses in his area. (O.R.

555) During this time Duncan Clark set up two industrial

luncheons. After Grigsby gathered his information and the

luncheons were held, he attempted to obtain signed contracts,

but faced the following obstacles: (1) the program was new and

had to be explained in detail to each business; (2) the program

was in "contract" form; (3) there was a fee provision in the

contract; (4) Grigsby was not allowed to demonstrate how the

program worked; (5) some of the businesses were waiting to see

how-the program worked at other companies; and (6) Grigsby was

black and all of the businesses were managed by whites.

Because of the aforementioned obstacles, the program

was not accepted initially by the businesses. However, the

program was not being accepted well in other regions of the State

of Mississippi. (Tr. Tr. 580) Around April, 1974, the program was

revised with the burdensome "contract" and the fee provisions

deleted. (O.R. 540) Grigsby again diligently sought industry

- 15 -

participation. (Tr.Tr.542) He obtained his first signed agree

ment in June, 1974, and his second, third, fourth and fifth

between June and August, 1974. In January, 1974, Clark had told

Grigsby to get four signed contracts within his first year, and

this requirement had been exceeded. Nevertheless, Grigsby was

terminated on August 14, 1976, through a letter praising him

for his initiative, enthusiasm, cooperativeness and responsibility.

He was told that the program would take a clinical approach for

which he was not qualified. (Exhibit "B" hereto)

Grigsby was replaced with a white, Douglas Von Horn,

who also had a Bachelor's and a Master's Degree. He was fresh

out of school and had no supervisory experience in industry.

(O.R. 738, 739)

Compare the experience of Grigsby with that of Eldridge

Flemings, a white man hired in June, 1969, as Director of Education

and Alcoholism Programs. His first assignment was to develop

an "Industrial Alcoholic Rehabilitation Program," (O.R. 202)

remarkably similar but narrower in scope to Grigsby's "Occupa

tional Health Program." (O.R.210) After six months, Flemings

was not able to obtain one signed agreement. (Tr.Tr.192,1202)

However, Flemings was not terminated; his title was merely

changed from "Director of Education and Aicohol Programs" to

"Director of Alcohol Programs^" (Tr. Tr. 186)

Eddie Black, a black intervenor, holds a Bachelor's

Degree in Social Science. (P.Exh.87) He, with Alvin Thomas,

16

■ m -mt-hmfivu' ~ m V ■■'T'N

j also black, was hired in July, 1972, as a Manager-Counselor

of a New Life Center, a walk-in facility for alcoholics,

located in the black community of Tupelo, Mississippi and

a facet of the alcoholics program of the Mental Health

Complex. Three other black employees were also employed

in the program, all in inferior positions. (Tr.Tr.468-69,

Def.Exh.25) Supervising this program were two white men:

Buddy Ramage, the Coordinator of Counsellors and Eldridge

Flemings, the Director of the Alcoholism Program, both sta

tioned in the Mental Health Complex in Tupelo. Intervenor

Black contends that upon Ramage1s resignation he, and other

black employees, were denied the Coordinator of Counsellors

position because of their race.

assigned to the Mental Health Complex and for six weeks per

formed most of the duties formerly assigned to Ramage.

(Tr.Tr.473, P.Exh.110) Thereafter, Black attended Atlanta

University where he earned a Diploma in the Alcoholism Counselor

Program which qualified him "to work with individuals, groups, and

and communities on the problem of alcoholism." (P.Exh;86)

This background, and the guidelines of the program and regu

lations of the Medical Center affording incumbents a prefer

ence for all promotions and vacancies, (P.Exh.105 and 32)

suggested that plaintiff intervenor or Mr. Thomas should have

received the vacant Coordinator of Counsellors position.

Upon Ramage’s departure, Black and Thomas were

-1 17

y The Coordinator position was filled on July 2, 1973,j

with a new employee, Kelly Ferguson, a white male. He had only

5 a Bachelor's Degree and had no counselling experience except

for that obtained while working in a half-way house in the Army.

(P.Exh.64, p.35r, Tr.Tr.458) Thereafter, Black and Thomas com

plained to the EEO officer of "LIFT" (the funding source for the

5 program), (Tr.Tr.886), which resulted in Flemings compiling a

statement of why none of his black employees was promoted.

‘.I

(D.Exh.25) Flemings then called a meeting of such employees

. and advised them of his disposition. (Tr.Tr.475) Thomas

resigned in frustration. Black filed a charge of racial discrimi

nation with the EEOC and also resigned somewhat later. Plaintiff's

claim of unlawful discrimination was upheld by the EEOC in a

compelling determination:

"In summary, the evidence indicates that Charging

Party's original application indicated that he

desired the position of Coordinator of Counselors,

that at the time this position was filled he and

another black employee were carrying out most of

the duties of this position, and Charging Party's

performance had been highly rated by his super

visor just a few months prior to this position

being filled. Further^the record shows that

while the staff was told that the position would

not be filled, the Director of the Program pro

ceeded to fill the position without internal

announcement of the vacancy to the staff, which

employees, without exception, said had been done

in the past. Finally, while all the decision

makers regarding this position were white, the

two staff members, both black, who, by virtue

of having been carrying out the functions of the

job, would have to be considered leading con

tenders for it, were not even told that a vacancy

existed and thus given an opportunity to apply

and be interviewed for the position." (P.Exh.90, p.5)

- 18 -

-f h . ~ r ' V , ; ‘ J- - ' . * ■ * ■ ' ,« !» *

--a* ii V v.. ---:• ~^--- - ru-ĝ -v̂ -v-:.- ,-%_w--- --

Essie Sneed, a black, was employed by the North

Mississippi Medical Center on December 17, 1975, as a nurse's

aide. Sneed has an 11th grade education, has six children and

had previous work experience mostly as a housemaid. The job

as nurse's aide entailed serving breakfast, taking temperatures,

and assisting the nurses in other various duties. (R.vol.IV,pp.622,623)

After working at the Medical Center for a few weeks,

Sneed injured her back while lifting a patient in bed. She was

immediately sent to the emergency room where she was treated

by Dr. Harris (an employee of the Medical Center) who advised

her to remain off work and attend therapy sessions. Sneed

returned to work a few weeks later and had a re-occurrence of

back problem. Sneed obtained medical treatment while she

continued to perform her duties. Defendant terminated plaintiff

on March 5, 1974, while she was hospitalized for her on-the-job

injury. (R.vol.IV, pp.624,625,627)

The Medical Center has a 90-day probationary period

during which an employee can be fired for any reason. Plaintiff

was within the 90-day period when she was fired for absenteeism.

However, it is also the policy and practice of the hospital not

to fire a person for absenteeism if the employee is hurt on the

job:

BY THE COURT:

Q. Is there any exception to that

rule where an employee is hurt

on the job? Do you mean you have

a rule there that during the

j& a ta e a a u a fa < a M h -VV .

period [of probation] if the

employee suffers an injury on

the job, that to take sick

leave or be away from work on

account of injury would for

feit her right to complete

her employment?

A. No sir, that is not what I

meant to say. Our sick leave

policy for employees injured

on the job differs from our

policy that deals with em

ployees who become ill on

their own. If an employee

were hurt on the job we would

certainly extend the probation

ary period to make sure that we

had a full three months to look

at them and have a full three

months to look at us.

(R.vol.IV,p.826, testimony of

Barry Wright, Personnel Manager).

It is undisputed that (1) the policy of the hospital

is to not fire a probationary employee for absenteeism if related

to on-the-job injury; (2) Sneed was injured on the job and

indeed was hospitalized as a result ,at the time of her dis

charge; (R.vol.II, pp.77,80) (3) the treatment accorded Sneed

was different from that accorded white employees under similar

circumstances; (R.vol.IV, pp.628,637) (4) the Medical Center

provided no explanation for its treatment of Sneed, nor could

it name any whites who had been similarly treated.

20

ARGUMENT ONE

Plaintiffs Established a Priraa Facie Case of

Class Discrimination.

The district court's bench opinion at first addressed

only the named plaintiffs' individual claims of discrimination.

After specific inquiry from plaintiffs' trial counsel, the court

provided the following - and only the following - explanation of

its decision as to the class:

Although the Court is of the opinion that

the named plaintiffs and plaintiff intervenors

made out a prima facie case on their individual

claims, the Court believes that the proof was

wholly insufficient to make out a prima facie

case against the defendant as to the plaintiff

class. Accordingly, the burden of proof never

shifted to the defendant on the class issue.

(Tr.Tr. 914-915)

A prima facie case of racial discrimination, under

Title VII, is established by statistics alone. "The inference

[of discrimination] arises from the statistics themselves and

no other evidence is required to support the inference." United

States v. Hayes International, 456 F.2d 112, 120 (5th Cir. 1972).

Sagers v. Yellow Freight Systems, Inc., 529 F.2d 721, 729 (5th

Cir. 1976) (and see lengthy citation td additional authorities in

Sagers, 529 F.2d at 729, n. 16). The district court erred in not

finding for appellants in light of the compelling statistical case

and additional evidence of class discrimination.

With reference to the administrative personnel at

the Medical Center, there were 59 officers and managers as

of 1972, none of whom was black. From 1973 to 1975 there

were at all times either 25 or 26 officers and managers, (it

appears that 32 or 33 of the employees previously classified as

officers and managers were reclassified) none of whom was black.

The Medical Center has never employed a black in an administrative

* -»r

capacity, even though 27 percent of its work force is black and

even though it is located in an area that is 21 percent black

geographically. Furthermore, in 1975, of the 25 whites serving

as officials and managers, five had only a high school diploma.

In the business office - clerical personnel category,

racial discrimination is also demonstrated by statistics. From

4/

1971 through 1974, defendant's staff was entirely white; in 1974

the first black secretary was hired. The exclusion of blacks

from such positions through 1974 and the subsequent employment

of only one such person, is a facet of a prima facie case of

unlawful discrimination.

In Housekeeping, from 1971-74, appellee employed seven

or eight blacks and no whites. In May, 1975, one white (Ms. Nelson)

was transferred from Dietary to Housekeeping and immediately made

supervisory over the seven more qualified blacks.

4/ In 1973, defendant employed a black secretary to work at

the New Life Center which was located in the black community of

Tupelo and part of a specially and separately funded program; she

answered to Thomas and Black, two black employees of the same

program. 22

In 1971, appellee's Dietary Department consisted of

11 persons, eight of whom were black. From 1972 to 1974 it

consisted of ten persons, seven of whom were black. In 1975 it

consisted of nine persons, seven of whom were black. From 1971

through 1975 every white employee of the Dietary Department was

a supervisor.

t1 .

Although plaintiffs were not permitted discovery on

the termination practices of the whole hospital, appellee demon

strated that although blacks comprise only 27 percent of the work

force, they are 44 percent of those discharged.

Although plaintiffs could have successfully relied upon

the foregoing proof for their priraa facie case, they went much

further. They particularized the pattern revealed by the statistics

with proof of discrimination against individual employees. Thus,

it was demonstrated that defendant has employed a total of four

blacks as "paraprofessionals;" two (Prude and Coleman) were

discharged (not transferred) when funding for the special alcoholism

project was reduced; the remaining two (Black and Thomas) were

forced to resign when they were passed over for a critical promotion

awarded to a white man recruited from without the agency. Predict

ably, the position in question. Coordinator of Counselors, had

always been restricted to whites. Plaintiffs also demonstrated

that Ms. Nelson, made supervisor over all blacks in the Housekeeping

Department, had never before worked in that department and was

taught her responsibilities by the black employees in her charge.

- 23 -

.^■'.■■•^...^wi>,«■; ,

Aggravating matters, Ms. Nelson had previously been made .

supervisor in the Dietary Department after working there

part-time for two months.

Under well established indistinguishable

precedent plaintiffs made out a prima facie case of racial

discrimination against the defined classes. The district

court erred in holding otherwise.

24

'l l— L.. I— - .V, ~_a s-l. s--~ ..-■:. ,- . -< -

ARGUMENT TWO

Employment decisions based entirely

upon the subjective judgment of an

all-white supervisory staff which

result in the promotion of only whites,

or the employment of only whites for

positions of responsibility, or which

result in disproportionate discharges

of blacks, are violative of Title VII.

And defendant's discharge of plaintiffs

Grigsby and Sneed and its failure to

promote intervenor Black and similar

situated class members violated Title VII.

ii “

In Watkins v« Scott Paper Co., 530 F.2d 1159, 1193

(5th Cir. 1976), the Court found the following facts combined

to render defendant's promotion decisions violative of Title VII:

(1) the supervisor's recommendation for a promotion was critical;

(2) supervisors were not given written instructions controlling

their decisions? (3) standards in existence were "vague and

subjective;" (4) incumbent employees were not notified of

vacancies or the necessary qualifications; (5) there were no

_4/

"safeguards" to avert discriminatory practices.

J1

-4/ Watkins is merely recent authority for a principle

now entrenched. Rowe v. General Motors, 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir.

1972) ; Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Ref. Corp. 495 F.2d 437, 442

(5th Cir. 1974) United States v. N.L. Industries, Inc.. 479 F.2d

354, 367-68 (8th Cir. 1973). Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine

Co^ 457 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972).

25

All of the deficiencies enumerated in Watkins are

present in the case sub judice; T. Tr. 37-41, Pi. Exhibit 64,

Interrogatories, 40-41. It is clear, too, that these deficien

cies have resulted in blacks being passed over for all meaningful

promotions, since defendant freely admits that not one of its

black employees "in the ordinary course of his duties...exercises

general supervisory authority over any white person or persons."

(P. Exhibit 64, Interrogatory 43). The trial court erred in

not directing modifications to defendant's employment practices

required by Watkins.

The district court, perhaps in light of Watkins,

found that named plaintiffs had established a prima facie case

of unlawful discrimination. However, it found that prima facie

case rebutted by proof that defendant's decisions were made in

"good faith" and were not "illegally motivated:"

While it is no doubt true that

Mr. Grigsby holds a bachelor's

and a master's degree as does-

his successor, Mr. Van Horn, the

Court does not intend at this

point to pass upon the question

of whether Mr. Grigsby possesses

the necessary qualifications for

the job from which he was dis

charged or whether Mr. Van Horn

possesses qualifications superior

to those of Mr. Grigsby. The only

question which is now before the

Court and which the Court will

address is whether Mr. Grigsby's

discharge was prompted by illegal

motivation, that of race. In the

Court's mind, the evidence shows

that it was not.... More specifical

ly, the Court finds that Mr. Clark,

acting in good faith, discharged

Mr. Grigsby because he, Mr. Clark,

felt that Mr. Grigsby was not per

forming adequately. Whether Mr.

Grigsby's performance was adequate

or inadequate is not for the Court

to decide. (Tr. Tr. 902-903)

(emphasis added).

- 26 -

.M

S;

i.

_.r

Grigsby proved by a preponderance of the evidence

that he performed satisfactorily, that he possessed the

necessary qualifications for the position and that the white

who replaced him was not more qualified. The district court

required that Grigsby prove more- that he was intentionally

and in bad faith victimized. Title VII requires no such

proof. Local 189, United Paperwork v. United States. 416 F.2d

980, 996 (5th Cir. 1969). Albemarle Paper Go., v. Moody.

422 U.S. 405, 422-23, 45 L. Ed. 2d. 280, 299 (1975). In ad

dition, the district court's refusal to compare the qualifications

of named plaintiffs with those of the whites who obtained the

positions sought or held by named plaintiffs, was clearly

improper under controlling principles. East v. Romine Inc..

518 F.2d 332, 340 (5th Cir. 1975).

- 27 -

ARGUMENT THREE

Plaintiff Sneed's Prima Facie Case

Was Not Rebutted.

It was established that Essie Sneed was employed

by the Medical Center in December, 1973 as a nurse's aide

and that she was injured while performing that job. It was

further established that she was fired for absenteeism

necessitated by this injury in the face of a Medical Center

policy not to fire a person for absenteeism if it resulted

from an on the job injury; supra. pp. 19-20.

The District Court found that Sneed established

a prima facie case and required defendant to come forward

with rebuttal evidence. (T. Tr. 911) The one witness

presented by the Medical Center testified that it was not

the hospital's policy to fire an employee for absenteeism

related to an on-the-job injury. No other proof relating

to the merits was advanced.

Defendant apparently relies entirely upon the

fact this plaintiff, at her deposition, stated that she did

not think that her race was a factor in her treatment.

This "admission," explained and withdrawn by the plaintiff

at trial, is the sum and substance of defendant's defense.

(T. Tr. 634-646) We know of no Title VII requirement that

a named plaintiff be able to define racial discrimination

or know that she was so victimized. Judges and lawyers

expert on Title VII often erroneously find no discrimination.

- 28 -

K-

'i

C?

..

:;

:'

.-

-

v.

A

.

: .

AA

A.

.,

I.

'-

. .

■i

.-L

-..

:

.1

.

:--

---

---

A

t'-

.-.

,--

---

---

---

--i

__

■„

..

__

__

-

J

—

And this kind of admission by a plaintiff has been held

irrelevant to a Title VII claim. Rodricruez v. East Texas

Motor Freight. 505 F.2d 40, 59 (5th Cir. 1974).

Ms. Sneed filed this lawsuit claiming racial

discrimination; from that point forward the issue was not

whether she knew she was victimized but rather whether she

was in fact victimized.

ARGUMENT FOUR

The District court Improperly Limited

Discovery.

October 29, 1974, plaintiffs propounded a second

set of interrogatories against which defendant sought a

protective order. The district court, on January 2, 1975,

entered an order sustaining defendant's objections and

limiting discovery to the Mental Health Complex and the

Baldwyn unit. (O.R. 85-86, 89-90).

January 2, 1976, plaintiffs filed a motion for

class action certification. (O.R. 108) February 23, 1976,

the district court, on the basis of a lengthy and cogent

recommendation from the Magistrate, (O.R. 114-46), granted

class certification for all facets of defendant's operations.

Trial began on the very day this certification was granted.

And so plaintiffs faced the burden of proving across the

board unlawful discrimination at all of defendant's facilities

while under a January 2, 1975 order limiting discovery to

only two facets of defendant's operation.

- 29 -

' . ......

■-:v...l-1~± -;ai'..,_■ , . " • - '- -’------- ■ ~£ -» ■ .' - ■ --■_ : : ,'.■

Of course, the district court on January 2, 1975

did not anticipate the later broad class certification. But

no matter the explanation, plaintiffs could not possibly

adequately present proof of class discrimination in all

facets of the hospital without the discovery foreclosed by

the Court on January 2, 1975. And on remand plaintiffs

should be permitted to advance a more complete statistical

case. Burns v. Thiokol Chemical Corp. 483 F.2d 300, 306

(5th Cir. 1973).

- 30 -

>r * u (■min ♦ ■■-nr ,

1l

■4j;j

j

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons the following district court

determinations must be reversed: that no prima facie case

of class discrimination was established; that defendant did

not engage in any policy or practice violative of Title VII;

that defendant's successfully rebutted named plaintiffs'

prima facie cases; limiting discovery to two facets of

defendant's operation while certifying the case as a class

action for all facets. And the case should be remanded

for the entry of appropriate relief for the class and named

plaintiffs.

Respectfully submitted,

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

KENNETH MAYFIELD

303 1/2 West Main Street

Tupelo, MS 38801

Attorneys for Appellants

EXHIBIT A

Mental Health Complex and

Baldwyn Satellite Unit

EMPLOYEES BY RACE

HOUSEKEEPING DEPT.

Black White Total

Percentage

Black

Jan. 1, 1971 7 0 7 100%

Jan. 1, 1972 7 0 7 100%

Jan. 1, 1973 7 0 7 100%

Jan. 1, 1974 7 0

*/

7 100%

Jan. 1, 1975 7 1 8 87.5%

*/ The one white in the department is the supervisor. She

was transferred from the dietary department in May, 1974.(Tr.Tr.28)

DIETARY DEPT.

Black White

*/

Total

Percentage

Black

Jan. 1, 1971 8 3

*/

11 73%

Jan. 1, 1972 7 3

*/

10 70%

Jan. 1, 1973 7 3

*/

10 70%

Jan. 1, 1974 7 3

*/

10 70%

Jan. 1, 1975 7 2 9 78%

*_/ All the whites employed in the dietary department are

supervisors. (Tr. Tr. 32-35)

- 32 -

i3

:I■A

■ k ■•— a w / t -- ■ ■ » T ~ i '^ r j - v A . /> ¥ S u ' , - . U . ■-- « . , ^ ■ ',. f Y ^

Exhibit A page 2

BUSINESS OFFICE & CLERICAL PERSONNEL

Percentage

Black White Total Black

Jan. 1, 1971 0 11 11 0

Jan. 1, 1972 0

*/

12 12 0

Jan. 1, 1973 1 10 11 10

Jan. 1, 1974 0 15 15 0

Jan. 1, 1975 1 16 17 .06

V' This one black secretary was hired on a specially

funded Alcoholism Program. She was not working at the Main facility

of the hospital but was working at the New Life Center which is

located in a black neighborhood in Tupelo.

PROFESSIONALS (Excluding nurses)

Black

Jan. 1, 1971

~*7

1

Jan. 1, 1972

*/

2

Jan. 1, 1973

*/

4

Jan. 1, 1974

*,/

3

Jan. 1, 1975 */

2

Percentage

White Total Black

9 10 10

11 13 15

10 14 29

14 17 18

17 19 10

*/ All the blacks except one were employed in an al

coholism program which was specially funded project and is not

currently in effect. Moreover, by admission of defendants all

of the blacks are "paraprofessionals" in that their jobs do not

even require a high school education. The one black not included

in the alcoholism program was Otha Grigsby and he was discharged

and is a party to this lawsuit.

- 33 -

T.w’;■ 1 *t;̂:rr7r!:"-Pyf-

1-

u te a itk C>oynpLex. | | *30 *

SERVING. BENTON. CHICKASAW. ITAWAMBA. ' LEE. MONROE

PONTOTOC AND UNION COUNTIES

1<■

COUNTT OFFICES

BENTON COUNTY

Benton County Clinic Building

Ashland. Miuiuippi J8402

Phone 224-8883

CHICKASAW COUNTT

223 Eaat Washington

Houston, Mississippi 38SS1

Phone 453-4239

ITAWAMBA COUNTY

Crane Office Building

Bo* 87

Fulton. Mississippi 38843

Phone 852-9898 ------

MONROE COUNTY ^

East Comma re# Street

Box 18

Aberdeen, Miseiseippi 39738

Phone 449-2922

PONTOTOC COUNTY

Boone Building

Box 263

Pontotoc, Mississippi 38883

Phone 489-8141

UNION COUNTY

Room 11, Houston Buildins

Bankhead Street

New Albany. Mississippi 38882

Phono 534-5009

■1 - *

I. GLOSTER STREET • PHONE 801-848.3032 (EXT. 384)

TUPELO. MISSISSIPPI 38801

August 14, 1974

Mr. Otha Grigsby

Occupational Health Specialist *

Mental Health Complex

North Mississippi Medical Center

Tupelo, Mississippi 38801

Dear Otha,

Because of the limited response of industry to the Occu

pational Health Program, it will be necessary for your employ-

ment as Occupational Health Specialist to terminate on August 30,

1974 with two weeks additional pay in lieu of your annual vacation.

You are being 'laid off" rather than discharged. (See page 8 of

Employee's Handbook"). The reason is non-disciplinary be

cause of such "limited results on the^part of industry, as you and

I first discussed on May 8, 1974, and at which time.you were issued

a warning notice. This termination notice is in agreement w'ith our •

conversation <Jn June 28, 1974_at which time you were given two weeks'

notice and guaranteed a job-until July 12, at which time you would

go on a week to week" basis until a satisfactory replacement could

be secured. This is also wri-tteTi confirmation of our conversation

on August 12, 1974 at which time you were told that a satisfactory

replacement has been secured and that your last working day will be August 30, 1974.

The program will take another approach which will require a

specialist with clinical skills to provide clinical consultation to

personnel directors about their problem employees. I deeply regret-

that your training as a Sociologist does not include such a clinical orientation.

However, your initiative in this new program has provided a use--

.ful experience for the Mental Health Complex and the entire staff is

grateful for your initiative.-

This means that if you care to use the Mental Health Complex as

a reference in seeking employment, you will be given a positive

f t - % %

✓f \\ i£

EXHIBIT B

-1̂

ji

u

t.

i,

:..

-i

,.'

...

y

.

t

-

p

'

ia

Exhibit B -2- page 2

recommendation based on your enthusiasm, cooperativeness, and

responsibility.

Sincerely,

Duncan As Clark

. Center Director

Mental Health Complex

- £ L , < l - r

Elizabeth Ford \

Assistant Administrator

North Mississippi Medical Center

DAC/pp