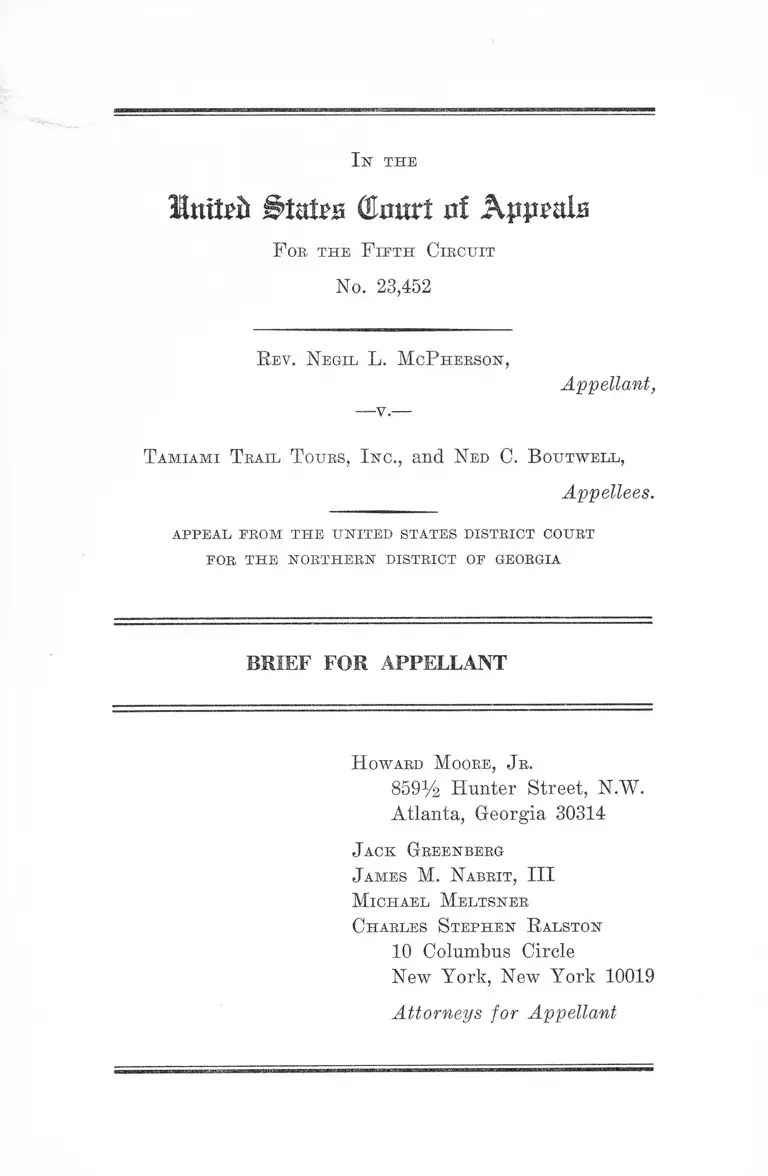

McPherson v. Tamiami Trail Tours, Inc. Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

August 19, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McPherson v. Tamiami Trail Tours, Inc. Brief for Appellant, 1966. 3eda76c0-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/409d8c07-0577-4d2a-98c7-7832a8be92c4/mcpherson-v-tamiami-trail-tours-inc-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

Itutefr ©Hurt uf Appals

F ob th e F if t h C ircuit

No. 23,452

R ev. N egil L . M cP herson ,

Appellant,

— v .—

T a m ia m i T rail T ours, I n c ., and N ed C. B out w e ll ,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

H oward M oore, J r .

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

J ack G reenberg

J ames M . N abrit , I I I

M ichael M eltsner

C harles S teph en R alston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellant

I N D E X

Statement of the Case ..................... -................................ 1

Statutes and Administrative Regulations ....................... 8

Specifications of Error ....................................................... 10

A k g u m e n t

I. On the Basis of the Uncontradicted Evidence,

the Appellees Failed to Exercise That Degree of

Care Owed to a Passenger by a Common Car

rier ........ 11

II. As a Matter of Law on the Basis of the Un

contradicted Evidence, Appellant Is Entitled to

Recover Under Section 1983 of 42 United States

C ode............................................................................ 15

Co n c l u s io n ......................................................................................... 20

Certificate of Service........................................................ - 21

T able oe Cases

Andrews Taxi & U-Drive It Co. v. McEver, 101 Ga.

App. 383, 114 S.E.2d 145 (1960) ................................ 12,13

Atlanta Transit System, Inc. v. Allen, 96 Ga. App. 622,

101 S.E.2d 134 (1957) ........ ............ -.............................. 12

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F.2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961) --------- 17

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F.2d 531 (5th

Cir. 1960) .......................................................................... 16

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454 ......... — ...... ..... .... — 18

Brazier v. Cherry, 293 F.2d 401 (5th Cir. 1961) ........... 19

PAGE

ii

Brown v. Board of Ed., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .............- 18

Brown v. State of Mississippi, 297 U.S. 278 (1935) .... 19

Bullock v. Tamiami Trail Tours, Inc., 266 F.2d 326

(5th Cir. 1959) .... ............ ........ .................... 13,15,17,19, 20

Catlette v. United States, 132 F.2d 932 (4th Cir. 1943) 16

Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64 (1937) ............ 12

Flemming v. S. Car. Elec, and Gas Co., 224 F.2d 752

(4th Cir. 1955), 239 F.2d 277 (4th Cir. 1956) ........... 16

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 (1961) ...... ..... ......... - 16

Hillman v. Ga. R. and Banking Co., 126 Ga. 814, 56

S.E. 68 (1906) ......... ........ ................................................ 12

Lynch v. United States, 189 F.2d 476 (5th Cir. 1951) 16

Marshall v. Sawyer, 301 F.2d 639 (9th Cir. 1962) ....... 16

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1960) ............................16,17

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373 .................................. 18

Nesmith v. Alford, 318 F.2d 110 (5th Cir. 1963) ...... ...18, 20

Samuels v. State, 103 Ga. App. 66, 118 S.E.2d 231

(1961) ..... ....... - ....... - ....... -.............................------.......... 13

Savannah Transit Co. v. Odum, 105 Ga. App. 740, 125

S.E.2d 538 (1962) ........................................... -............... 12

Sherrod v. The Pink Hat Cafe, 280 F. Supp. 516 (N.D.

Miss. 1965) .......... .............. .......................... -................... 19

United States v. Guest, 383 U.S. 745 (1966) ................... 19

United States v. Simmons, 346 F.2d 213 (5th Cir.

1965)

PAGE

11

Ill

United States v. Williams, 341 U.S. 97 (1950) .......... . 19

United States v. Wood, 295 F.2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961) 19

United States ex rel Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F.2d 71

(5th Cir. 1959) .............................. ................................... 13

Williams v. Wallace, 240 F. Supp. 100 (M.D. Ala.

1965) .............. ...... ....................... ..................................... 16

Yellow Cab Co. of Atlanta v. Carmichael, 33 Ga. App.

364, 126 S.E. 269 (1925) ........ ...... ............................... 12

F ederal S tatutes

28 U.S.C. §1332(a) (2) ...................................... ............... 1

28 U.S.C. §1343 (3), (4) .................................................... 1

42 U.S.C. §1983 (1958) ....................... ...................1,2,15,16,

17,19, 20

42 U.S.C. §1988 (1958) ..................................................... 19

State S tatutes and R ules

Ga. Code Ann. §18-204 (1963 Supp.) ........ ................ 8,12,19

Ga. Code Ann. §18-207 ...........................................8,16

Ga. Code Ann. §68-616 ........... . 9

Ga. Code Ann. §68-710 . 9

Ga. Code Ann. §105-202 ......... ................................9,13

O ther A uthorities

2B Barron and Holtzoff (Wright, ed.) .......................... 11

6 Moore’s, Federal Practice ....... ..... ......... ....................... 11

Wright, Federal Courts .... ...................... ........ ................ 11

PAGE

I n T H E

United States (&m xt nf Appeals

F or t h e F if t h C ircuit

No. 23,452

R ev. N egil L. M cP herson ,

Appellant,

T am ia m i T rail T ours, I n c ., and N ed C. B outw ell ,

Appellees.

a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n it e d s t a t e s d is t r ic t c o u r t

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from a denial of motions for directed

verdicts and for judgment notwithstanding the verdict or,

in the alternative, for a new trial in a civil action for

damages brought Sin the District Court for the Northern

District of Georgia. The complaint was filed on April 19,

1963, and invoked the jurisdiction of the court under 28

U.S.C. §§1332(a) (2), 1343(3) and (4), and 42 U.S.C. §1983.

The matter in controversy exceeds the sum of $10,000.00,

damages in the amount of $80,000.00 having been sought

against the defendants jointly and severally.

The plaintiff, appellant here, is a citizen of the Common

wealth of Jamaica, residing in Springfield, Illinois. There

2

is diversity of citizenship between the parties since Tami-

ami Trail Tours, the corporate defendant, is organized

under the laws of the State of Florida and does business

in the State of Georgia, while the individual defendant is

a citizen of the State of Georgia. Jurisdiction was also

based on the federal civil rights statutes, 42 U.S.C. §1983,

in that the corporate defendant, acting by and through its

agent and employee, Ned C. Boutwell, the individual de

fendant, who, while acting under color of Georgia state

statutes, regulations, customs, and usages, injured the

plaintiff, and deprived him of rights and privileges under

the Constitution and laws of the United States.

Under the first count of the complaint, based on diversity

of citizenship, it was alleged that Tamiami Trail Tours,

acting through the individual defendant as its agent, failed

to exercise the degree of care legally owed to the plaintiff,

with the result that the plaintiff suffered great bodily in

jury and harm. Briefly, the complaint alleged that on

September 22, 1961, the plaintiff got on a bus owned and

operated by the corporate defendant, the driver of which

was the individual defendant Boutwell. The plaintiff, who

is a Negro, sat in the front part of the bus. Defendant

Boutwell, although he had reason to believe that white

persons who were also passengers in the bus were hostile

towards the plaintiff because of where he was sitting, did

not take reasonable steps to insure the safety of the plain

tiff, as required under Georgia law. While the bus was

proceeding along its route, one of the white passengers

assaulted the plaintiff and beat him severely about the

face, throat and head. Again, it was alleged, defendant

Boutwell did not take reasonable steps to protect the

plaintiff. Moreover, the defendant failed to report the

incident to the police or to secure medical aid for the plain

tiff. Because of this neglect and failure to act on the part

of defendant Boutwell, the agent of the bus company, the

3

plaintiff suffered great bodily pain and injury and mental

anguish, in addition he lost, and will in the future lose,

great sums of money (R. 408, 414).

The defendants filed an answer in which they generally

denied the factual allegations of the complaint and denied

that they owed any duty to exercise a greater degree of

care towards the plaintiff than they did exercise. Con

tributory negligence was not pleaded as a defense (R. 417).

At the trial on July 6, 7, and 8, 1965, the following was

adduced in evidence:

The appellant testified that on September 22, 1961, he

went to the Trailways Station in Atlanta, Georgia, and

purchased a ticket to Griffin, Georgia, on a bus leaving at

5 :45 p.m. After buying the ticket, he went to the loading

zone where the bus was expected. When he arrived at the

zone, he stood behind the only other passenger waiting, a

female (R. 51). During the twenty minutes before the bus

arrived, a number of other passengers gathered. Appellee

Ned C. Boutwell then drove his bus into the zone, went

into the terminal, came out, and began collecting tickets

(R. 52). After the driver took the ticket of the lady in

front of the appellant, the Reverend McPherson extended

his arm to sirrrender his ticket, but Mr. Boutwell reached

over his arm and took tickets from a number of other

persons before taking his (R. 53).

Reverend McPherson then got on the bus and sat in the

fifth seat from the front on the side of the door. At the

time, there were only four other persons on the bus, in

cluding two white men sitting one seat behind the appel

lant on the opposite side (R. 56). The bus driver then came

into the bus and told McPherson, “Your seat is in the back”

(R. 57). McPherson did not move. The driver went out

side and collected more tickets. He then returned to the

4

bus and again told Reverend McPherson, “Your seat is in

the back” (R. 57). The appellant again did not move. The

driver then had a conversation with the two white men

sitting behind the appellant on the opposite side of the bus

(R. 57). After this conversation, the driver returned to

the appellant and again said, “Your seat is in the back.”

When Rev. McPherson asked, “Why?” the driver replied,

“I don’t care if anyone jumps you” (R. 57).

The driver then left the bus. One of the men sitting to

the rear of Reverend McPherson, with whom the driver

had spoken, approached McPherson and asked, “Why don’t

you do as the man said?” (R. 57, 58) and, “Where are you

going?” (R. 58). When he did not answer, the man said,

“ You may not reach where you are going” (R. 58).

Subsequently, the driver returned to the bus and the

journey began. McPherson did not tell the driver of the

threat he received because he felt, in view of the driver’s

abusive treatment, that it was pointless (R. 115, 127).

While the bus was traveling along the highway, the man

who had previously threatened McPherson approached

him and asked, “Why didn’t you do as the bus driver and

I told you?” (R. 58). The Reverend replied that in his

country people sat wherever there was a vacant seat, where

upon the man said, “You are not in your country now and

I am going to kill you” (R. 59). He began to beat the ap

pellant on the head, face, and throat with an object which

he had clenched in his fist. McPherson cried out and pulled

the cord to stop the bus (R. 59). The driver stopped the

bus, got out, and stood outside for several minutes. An

other man, subsequently identified as Mr. Edward Augustus

Hicks, came all the way from the rear of the vehicle and

attempted to stop the beating (R. 60).

The bus driver then returned to the bus. Mr. Hicks took

Reverend McPherson to the rear of the bus and the as

5

sailant followed, telling him to sit down, and “ This is where

[yon] belong” (R. 60). The driver then drove on, made

a regularly scheduled stop in Jonesboro, and continued to

ward Griffin. On the highway between Jonesboro and

Griffin, the driver stopped the bus and handed out slips of

paper to get the names of witnesses to the assault.

McPherson got off the bus at Griffin, his destination,

and was taken by his wife, a school teacher whom he had

recently married, to the Griffin Spalding Hospital for four

hours of treatment for his injuries (R. 63, 64). McPherson

testified that as a result of the injuries he received on the

bus, his ability to continue theological study was severely

impaired, as was his ability to work as a pastor (R. 70).

The injuries resulted in permanent damage to his nasal

passages with concomitant sore throat and hoarse voice.

Appellant also suffers from recurrent headaches (R. 77).

The bus driver Boutwell testified that he had worked for

the bus company as a driver for about 11 years, and that

he did not take McPherson’s ticket when it was first pre

sented because he believed that he had stepped in front of

others ahead of him in line (R. 162). He further testified

that he hard “ grumbling” among other people waiting in

line. He interpreted this as indicating resentment against

McPherson because he had tried to go ahead of persons in

line. He also testified that he told appellant to move from

his seat because of the grumbling that he heard (R. 182,

183). Appellee Boutwell testified that he heard some per

sons and waiting passengers make statements such as, “ I

will take care of him,” or “ He should be taken care of,”

but he did not inform McPherson of the remarks (R.

183, 184). Nor did he attempt to find out who made the

remarks (R. 184). Boutwell did not explain to the appel

lant why he believed it would be better for him to move

further towards the rear of the bus. He first told appel

6

lant to move because: “Well, I asked you to” (R. 187).

He also testified that he told the appellant to move for his

own safety (R. 188).

Boutwell testified that he responded to the question of

the two white men in the seat to the rear of McPherson

when they asked if they could get off any place along the

road (R. 191). He also said that he had no reason to

believe these men had made remarks outside the bus,

however, he made no investigation to determine whether

those making the remarks had boarded the bus (R. 192).

The driver admitted he drove the bus off from Atlanta

without reporting the incident or remarks to the station

superintendent or others in charge (R. 195).

The driver testified that at the time the incident oc

curred he stopped the bus when someone rang the bell

(R. 199). He further testified that although he heard the

appellant cry out to him (R. 200), he did not immediately

proceed back in the bus, but instead got off the bus to

allow other passengers to unload first (R. 200, 201). He

stated that, “ This lady and little girl wanted to get out

side” (R, 201).

After the driver reentered the bus, he saw the assailant

slapping McPherson. The assailant pushed him back down

the aisle of the bus and out onto the ground (R. 203).

In the confusion, according to the driver, the assailant

disappeared (R. 203).

The bus driver then drove the bus to Jonesboro, his

next regular stop (R. 173). He admitted that he did not

notify the police at Jonesboro of the incident (R. 176),

nor did he notify the police upon reaching his next reg

ular stop at Griffin (R. 180). He did say that he stopped

the bus between Jonesboro and Griffin and took the names

of the passengers (R. 177), and that he did not stop

7

before then because he was not sure what he should do

(R. 178). On direct examination, the bus driver denied

that he made a statement to the effect that he did not

care if anyone jumped the appellant, as the Reverend

McPherson had testified (R. 225).

Other testimony was given by witnesses for the appel

lant, primarily as to the extent and nature of his injuries

(R. at 138, 238, 252). Regulations and laws pertaining to

the seating of passengers in Georgia in effect at the time

of the incident wore introduced in evidence. These reg

ulations required segregation according to race on buses

operating in Georgia (R. 283).

On rebuttal, the chief witness for the appellees was Mr.

Edward Augustus Hicks, the passenger who intervened in

the attack on McPherson. He testified that after he saw

a white man hitting or threatening to hit the appellant,

he went forward and tried to reason with him to leave

McPherson alone (R. 308). He also saw that the driver

was off the bus assisting passengers to get down. After

the driver returned to the bus, he told the assailant he

would have to leave the bus (R. 309). When the assailant

pushed the driver toward the front of the bus, Hicks

caught him by the shoulder and ordered him not to bother

the driver (R. 309). The assailant pushed by Hicks and

began beating McPherson. Hicks, together with the driver,

managed to pull the assailant off, after which he took

the appellant to the rear of the bus (R. 309). The as

sailant followed them to the rear and Hicks said, “Now

leave him alone. He is in the back of the bus.” There

upon, the assailant brushed past the driver and left the

bus through the open door (R. 310). As soon as the as

sailant escaped, the driver started up the bus and drove off.

Another witness for the appellees, Miss Loretta Joyce

Kelly, described the incident as follows: “ The boy kept

8

telling him to move back, and he didn’t move, and so

then the boy just got u p ' and started beating him” (R.

332). (The “boy” was a man between 28 and 35 years old

(R. 336). She also testified that the driver initially left

the bus, returned, and the assailant pushed by him and

escaped (R. 333).

At the close of the evidence, the plaintiff requested

directed verdicts from the Court, which were denied (R.

525, 543). After the jury returned a verdict on the first

claim for the appellee carrier and on the second claim

for both appellees (R. 406, 526, 527), a motion for judg

ment not withstanding the verdict or, in the alternative,

for a new trial was likewise denied (R. 545, 547). A notice

of appeal was timely filed on September 23, 1965 (R. 547).

Statutes and Administrative Regulations

This case involves the following statutes of the State

of Georgia and regulations of the Public Service Commis

sion of the State of Georgia :

18 Georgia Code A nnotated , S ection 204:

“Diligence required of carriers.—A carrier of pas

sengers must exercise extraordinary diligence to pro

tect the lives and persons of his passengers, but is not

liable for injuries to them after having used such

diligence.”

18 Georgia Code A nnotated , S ection 207:

“Duty to assign passengers to their cars; police

powers of conductors.—All conductors or other em

ployees in charge of passenger cars shall assign all

passengers to their respective cars, or compartments

of cars, provided by the said companies under the

9

provisions of section 18-206 and all conductors of

street cars and busses shall assign all passengers to

seats on the cars under their charge, so as to separate

the white and colored races as much as practicable;

and all conductors and other employees of railroads

and all conductors of street cars and busses shall

have, and are hereby invested with, police powers to

carry out said provisions. (Acts 1890-1, p. 157 .)”

105 Georgia C ode A nnotated , S ection 202:

“Extraordinary diligence. Slight negligence.—In

general, extraordinary diligence is that extreme care

and caution which very prudent and thoughtful per

sons exercise under the same or similar circumstances.

Applied to the preservation of property, extraordinary

diligence means that extreme care and caution which

very prudent and thoughtful persons use in securing

and preserving their own property. The absence of

such diligence is termed slight negligence.”

68 Georgia C ode A nnotated , S ection 616:

“ Carriage of white or colored passengers or both.—

Motor common carriers may confine themselves to

carrying either white or colored passengers; or they

may provide different motor vehicles for carrying

white and colored passengers; and they may carry

white and colored passengers in the same vehicle, but

only under such conditions of separation of the races

as the Commission may prescribe.” (Acts 1931, pp.

199, 204.) (Georgia Public Service Commission Laws

and Buies, issued January 1, 1963, p. 200.)

68 Georgia Code A nnotated , S ection 710:

“Proof of injury prima facie evidence of want of

reasonable care and skill.—In all actions against per

10

sons, firms or corporations operating busses for hire,

for damages done to persons or property, proof of

such injury inflicted by the running of busses of such

person, firm or corporation, shall be prima facie evi

dence of want of reasonable skill and care on the

part of the servants of said person, firm, or corpora

tion in reference to such injury.” (Acts 1929, pp. 315,

316.) (Georgia Public Service Commission, Laws and

Rules, issued January 1, 1963, p. 206.)

Specifications of Error

The Court below erred in denying the appellant’s mo

tions for directed verdicts on the first and second claims

of the complaint and likewise erred in denying and over

ruling appellant’s motion for judgment notwithstanding

the verdict or, in the alternative, for a new trial. Similarly,

the jury erroneously returned verdicts for the appellees

in view of the evidence adduced at trial and in light of

Georgia law establishing the duty of care owed to a pas

senger by a common carrier.

11

I.

On the Basis of the Uneonlradicted Evidence, the

Appellees Failed to Exercise That Degree of Care Owed

to a Passenger by a Common Carrier.

A. The court below erred in denying appellant’s mo

tions for directed verdicts, for judgment notwithstanding

the verdict or, the alternative, for a new trial.

It is settled law that a motion for judgment notwith

standing the verdict renews an earlier motion for directed

verdict, and that the applicable judicial standard is the

same in each case. On such motions, the evidence must be

construed in the light most favorable to the party against

whom the motion is made. The court then determines

whether, under the law, such evidence might render a

verdict for the party against whom the motion is made,

or if reasonable men could differ as to the conclusions of

fact to be drawn. If either is the case, the motion should

be denied. United States v. Simmons, 346 F.2d 213 (5th

Cir. 1965); Wright, Federal Courts, §95 at p. 370; 2B

Barron and Holtsoff, §1075; 6 Moore’s, Federal Practice,

Section 59.08 at p. 3814.

In the instant case, for both the first and second claims,

the undisputed and uncontradicted evidence, construed in

any light, reveals that appellant’s motions should have

been granted. The uncontradicted evidence shows no evi

dence of actions on the part of the bus driver which

meets the high standard of care required of carrier drivers.

In addition, the uncontradicted evidence shows that the

driver’s actions violated McPherson’s civil rights. It should

be noted that contributory negligence is not at issue here,

for it was neither pleaded nor charged, and any care

12

rendered by the carrier’s driver after the rights of the

appellant had been violated is irrelevant.

B. Under Georgia law, which is applicable to the First

Claim, brought on the basis of diversity of citizenship,

a common carrier has the duty to exercise “extraordinary

care and diligence” to protect its passengers. Erie R. Go.

v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64 (1937); Atlanta Transit System,

Inc. v. Allen, 96 Ga. App. 622, 101 S.E.2d 134 (1957). This

protection extends to danger from known or reasonably

observable outside sources. Savannah Transit Co. v. Odum,

105 Ga. App. 740, 125 S.E.2d 538 (1962). Outside sources

include third persons. Hillman v. Ga. R. and Banking

Co., 56 S.E. 68 (1906). Perhaps the fullest statement of

the duty of common carriers is found in Yellow Cab Co.

of Atlanta v. Carmichael, 33 Ga. App. 364, 126 S.E. 269

(1925) at 271:

A common carrier of passengers is bound to use

extraordinary care and diligence to protect its pas

sengers in transit from violence or injury by third

persons; and whenever a carrier, through its agents

and servants, knows, or has opportunity to know, of a

threatened injury to a passenger from third persons,

whether such persons are passengers or not, or when

the circumstances are such that an injury to a pas

senger from such a source might reasonably be an

ticipated, and proper precautions are not taken to

prevent the injury, the carrier is liable for damages

resulting therefrom.

(See also Title 18, Ga. Code Ann. 204, supra, p. 8.)

Extraordinary care and diligence is defined as that

extreme care and caution which very prudent and thought

ful persons would exercise under the same or similar cir

cumstances. Andrews Taxi & U-Drive-It Co. v. McEver,

13

101 Ga. App. 383, 114 S.E.2d 145 (I960), Title 105, Ga.

Code Ami. 202, supra, p. 9.

C. That appellee Boutwell, agent of the bus company,

failed to fulfill his duty towards the passenger McPherson

is plain. It is undisputed that the driver spent his entire

life in the South and was familiar with regional customs

and folkways which included the long-established custom

of segregation on carriers and violence towards the Negro

who acted in violation thereof. Bullock v. Tamiami Trail

Tours, Inc., 266 F.2d 326 (5th Cir. 1959); United States

ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F.2d 71 (5th Cir. 1959);

Samuels v. State, 103 Ga. App. 66, 118 S.E. 2d 231 (1961).

The existence of such customs was sufficient to put the

driver on notice that McPherson was in danger, especially

in light of the passengers’ hostility to McPherson, when

he sat in the front of the bus, Bullock, supra. It is un

disputed that the driver did nothing to safeguard McPher

son. It is true that the driver requested the appellant

to go to the rear of the bus, but when the appellant, a

foreigner obviously unfamiliar with the custom did not

move,1 the appellee neither explained to him that he was

in danger nor took any steps to safeguard him. Having

told McPherson to move to the back, the driver did nothing

more. This was clearly a flagrant lack of prudence and

thoughtfulness.

The driver’s knowledge of the danger which his pas

senger was in was not limited to the folkways of the

South. It is undisputed that after the appellant boarded

the bus, the driver heard grumbling among those standing

outside it, including remarks that someone ought to “take

1 Appellant, a native o f Jamaiea, where there is no segregation, speaks

with a noticeable accent. He first came to this country in 1954, but had

lived in the deep south for less than a year prior to the incident.

14

care of” the appellant (R. 183). With this knowledge of

the hostility in his passengers, the driver did nothing

except tell McPherson to move to the rear, with no ex

planation as to why.

The driver failed to report the threats he heard to

the police or his superiors at the terminal. He made no

attempt to discover who had made the threatening remarks.

He made no announcement to the passengers that violence

would not be tolerated. He made no effort to change the

usual adjustment of his mirror, which would have enabled

him to keep all the passengers in the bus under observation.

All he did was tell the appellant to move to the rear, with

no explanation as to why.

Merely telling the appellant to move, in the hearing

of other passengers, any of whom might have uttered the

threats heard outside the bus, was hardly the act of an

extremely careful and cautious person. A reasonable driver

would have realized that his order, if disobeyed, as indeed

it was, would further inflame a tense situation. Nor would

an extremely prudent and careful person have readily

advised an inquiring passenger that he could get off any

where outside of town and encouragingly added “Just

reach up and pull the cord anyplace” (R. 191).

The driver admitted that after the incident he drove the

bus directly to his next regularly scheduled stop, let per

sons on and off, and then proceeded along the highway

for a mile before he pulled over and passed out slips of

paper to take the names of witnesses to the incident.

The driver admitted on cross-examination that it took him

so long to do this was because he had to make up his mind

as to what he should do (R. 178). This may explain the

driver’s conduct during the entire sequence of events, but

it does not amount to a defense, for the law demands that

15

he act as a very prudent and thoughtful person. The right

of action on the first claim is against the carrier, appellee

Tamiami Trial Tours, and it, therefore, cannot explain

Boutwell’s deficiencies to lessen its responsibility. Simi

larly, a very thoughtful person would hardly have let

McPherson, at the conclusion of his journey, go off in the

night without inquiring as to his condition or his need for

aid as did the driver.

On the basis of the uncontradicted evidence, this Court

should reverse the decision below and remand with direc

tions to enter a judgment for the appellant, with a new

trial to be upon the issue of reasonable compensatory dam

ages, for physical injury and mental suffering and humilia

tion. This case is controlled by the decision of this Court

in Bulloch v. Tamiami Trail Tours, Inc., 266 F.2d 326

(5th Cir. 1959), a case in which the facts are nearly iden

tical to those shown by this record.

II.

As a Matter o f Law on the Basis of the Uneontra-

dicted Evidence. Appellant Is Entitled to Recover Un

der Section 1983 o f 42 United States Code.

Section 1983 provides that:

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordi

nance, regulation, custom, or usage . . . subjects or

causes to be subjected any citizen of the United States

or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the

deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities

secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable

to the person injured in an action at law. . . .

The elements of recovery under this section are that (a)

the conduct complained of was engaged in under color of

16

state law, and (b) that such conduct subjected one to

deprivation of rights, privileges, or immunities secured

by the Constitution of the United States. Marshall v.

Sawyer, 301 F.2d 639, 646 (9th Cir. 1962); Monroe v.

Pape, 365 U.S. 167, 187 (1961).

The driver acted under the required color of law, both

in requesting the appellant to move to the rear of the bus

and in failing to protect him from violence. Section 207,

18 G-a. Code Ann., supra, p. 8, commanded the driver to

enforce the separation of the races upon the bus, and the

state law was buttressed by administrative regulations to

the same effect, supra, pp. 8-10. The driver was clothed with

further authority to maintain order in case of disturbance

and admitted the existence of that authority at trial

(E. 193). It is beyond question that their enforcement

of segregation laws renders a bus company and driver

liable for damages under 42 U.S.C. §1983. Flemming v.

South Carolina Electric and Gas Co., 224 F.2d 752 (4th

Cir. 1955); id., at 239 F.2d 277 (4th Cir. 1956). Cf. Boman

v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F.2d 531 (5th Cir. 1960).

The driver also took no precautions to prevent the as

sault or to subsequently arrest and apprehend the assailant

for whom he left the bus door open (E. 203, 310, 333).

The withholding of the protection of the State because

of race or color where the State is authorized to act is the

deprivation of the constitutionally protected right. See

Catlette v. United States, 132 F.2d 902 (4th Cir. 1943);

Lynch v. United States, 189 F.2d 476 (5th Cir. 1951);

Williams v. Wallace, 240 F. Supp. 100 (M.D. Ala. 1965).

The failure of the driver, who was empowered by the

State, to protect his Negro passenger comes under §1983

because it is a “lassitude” engendered by custom. Cf.

Mr. Justice Douglas, concurring in Garner v. Louisiana,

368 U.S. 157 at 178-79: “ . . . state policy may be as effec

17

tively expressed in customs as in formal legislative, execu

tive, or judicial action.” And see Baldwin v. Morgan,

287 F.2d 750 at 756 (5th Cir. 1961), granting an injunction

against policemen who customarily arrest Negroes found

in a white waiting room. Perhaps the most convincing

evidence that the failure to protect occurs under the color

of custom may he seen in Bulloch v. Tamiami Trail Tours,

Inc., 266 F.2d 328 (5th Cir. 1959), involving similar events

and the same corporate appellee.

Nor can the bus company and driver escape responsibility

for the brutal beating of McPherson on the ground that

it was done by an unidentified private person. Directly

after asking the appellant to move to the rear of the bus,

the driver spoke with two white men sitting behind Mc

Pherson, one of whom later attacked him. To claim that

there is no connection between the driver’s remarks to

the appellant, within hearing of those on the bus, his

failure to take preventive action to protect McPherson,

and subsequent action by those on the bus, would be to

define proximate cause with unnatural restrictiveness. It

should be remembered that §1983 “ should be read against

the background of tort liability that makes a man respon

sible for the natural consequences of his actions,” Monroe

v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 at 187. Conditions in the South

in 1961 with regard to the seating of the races render the

connection between the driver’s speech and the passenger’s

action far from tenuous.2

2 At trial, the appellee bus driver demonstrated his awareness o f these

conditions:

“ Q. . . . ‘Why would moving to the other side of the bus pro

tect him ? ’

“ Answer: ‘He would have been two or three seats farther back.’

“ Question: ‘And what effect would that have had on his alleged

assailants ? ’

“Answer: ‘Well, you know, all o f this desegregation has just be

gun to start a little after that, and you know how the people o f the

18

The right herein involved is the right to travel npon

an intrastate bus without being segregated. Morgan v.

Virginia, 328 U.S. 373; Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454.

Appellees deprived McPherson of the right to be free of

discrimination or segregation because of his race or color

while traveling upon an intrastate bus. The seat which

appellant first selected was convenient, comfortable, and

safe (R. 185, 186). The fact that this act of taking the

first unoccupied and convenient seat was “ offensive and

provocative” can in no way legally explain or justify the

bus driver’s direction to move further to the rear. See

Nesmith v. Alford, 318 F.2d 110, 121 (5th Cir. 1963). In

the context of this case, the act of directing appellant to

move to the rear to sate the racial preferences of white

passengers is discrimination per se. Merely informing the

appellant that his place was in the back of the bus sub

jected him to the humiliation and degradation of segrega

tion, whether or not he was actually forced to move, for

the primary effect of segregation is not so much physical

placement as it is the resulting state of mind of the person

discriminated against. See Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954). The rear of the bus is the traditional

place for the segregated Negro.3

South were still feeling about that time. I knew, you knew, and he

knew. All precautions you could take to keep anything down I

thought would be best.’ ” (R. 208).

3 Compare the testimony in this record, supra, p. 17, fn. 2, and the

following testimony of appellee Boutwell:

“ Q. Now, you didn’t tell the plaintiff that you overheard these

men outside saying these words, ‘I ’ll take care of him,’ or ‘He

should be taken care of’, did you? A. No.

“ Q. And so, Mr. Boutwell, when you heard this remark you de

cided you would go in the bus and take care of the plaintiff, didn’t

you? A. Not take care of him. As I stated before, I felt like it

would be a good idea, if someone had said it, or the ones, had al

ready gotten on the bus, it would be a good idea to get him out of

the area.

19

Appellant was also deprived of the right to move freely

upon highways and other instrumentalities of interstate

commerce within the State of Georgia. See United States

v. Guest, 383 U.S. 745 (1966), sustaining a criminal indict

ment charging a conspiracy to obstruct the rights of Ne

groes. Guest recognizes and protects “ the right to travel

freely to and from the State of Georgia and to use high

way facilities and other instrumentalities of interstate

commerce within the State . . . ” 383 U.S. 747, footnote 1

(emphasis added).

Not only was appellant subjected to the mental pains

and anguish of discrimination, but he was also severely

beaten for refusing to give up constitutional rights.4 Beat

ing a person attempting to enforce his rights is the most

obvious unlawful deprivation of those rights, for §1983 ex

presses “a clear Congressional policy to protect the life of

the living from the hazard of death caused by unconstitu

tional deprivation of civil rights . . . ” Brazier v. Cherry,

293 F.2d 401 (5th Cir. 1961); Sherrod v. The Pink Eat

Cafe, 250 F. Supp. 516 (N.D. Miss. 1965). See also, United

States v. Wood, 295 F.2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961); United States

v. Williams, 347 U.S. 97 (1950); Brown v. State of Missis

sippi, 297 U.S. 278 (1935).

Under §18-204 Ga. Code Ann., applicable to the federal

cause of action pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §1988, the driver,

acting as agent for the bus company, owed appellant a

“ Q. You asked him to move because of remarks you had heard

outside; is that right? A. That’s correct.” (R. 184, 185).

See further the testimony of an assailant upon a Jamaican Negro who

rode in the front of the bus:

“ A. . . . he was out of place in my opinion in the front of the bus.

“ Q. Is it a practice that all colored people in Perry have to move

back? A. Yes.” Bullock v. Tamiami Trail Tours, Inc., supra, at

328, 329, fn. 1.

4 Appellant required four hours of hospital treatment following the

beating, and he continues to sutler complications (256, 259, 263).

20

duty to exercise extraordinary diligence to protect Mm

from a known danger, liere the threats of racially hostile

passengers, or from one reasonably to be anticipated. The

driver did nothing and in fact fanned the flames of resent

ment.

Uncontradicted evidence establishes that appellant is en

titled to a directed verdict upon his §1893 claim. Cf.

Bullock, supra, where this Court, on the same facts, re

versed a decision in favor of the defendants and remanded

with directions to enter a judgment for the plaintiffs and to

award reasonable compensatory damages for physical in

jury, mental suffering, and humiliation. See also, Nesmith,

supra, at 124, where the Court held that appellants’ mo

tions for an instructed verdict of a §1983 claim should

have been granted at trial where there was no doubt that

the appellees were acting under the color of state law and

that their conduct violated the civil rights of the appel

lants.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment below should

be reversed with directions.

Respectfully submitted,

H o w a r d M o o re , J e .

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

J a m e s M . R a b b it , 111

M ic h a e l M e l t s n e r

C h a r l e s S t e p h e n R a l s t o n

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellant

21

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that on the 19th day of August, 1966, I

served a copy of the foregoing Brief for Appellant upon

attorneys for appellees, by United States mail, air mail,

postage prepaid, addressed to the following:

John S. Langford, Jr., Esq.

M. D. McLendon, Esq.

Bryan, Carter, Ansley & Smith

924 Citizens & Southern National Bank Bldg.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

Attorney for Appellant

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. ■■■«%&■■■ 219