New Jersey v. Cooper Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1948

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. New Jersey v. Cooper Brief Amicus Curiae, 1948. 79cdb45e-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/40bd9205-3e08-4b36-af68-dd1d197727b3/new-jersey-v-cooper-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

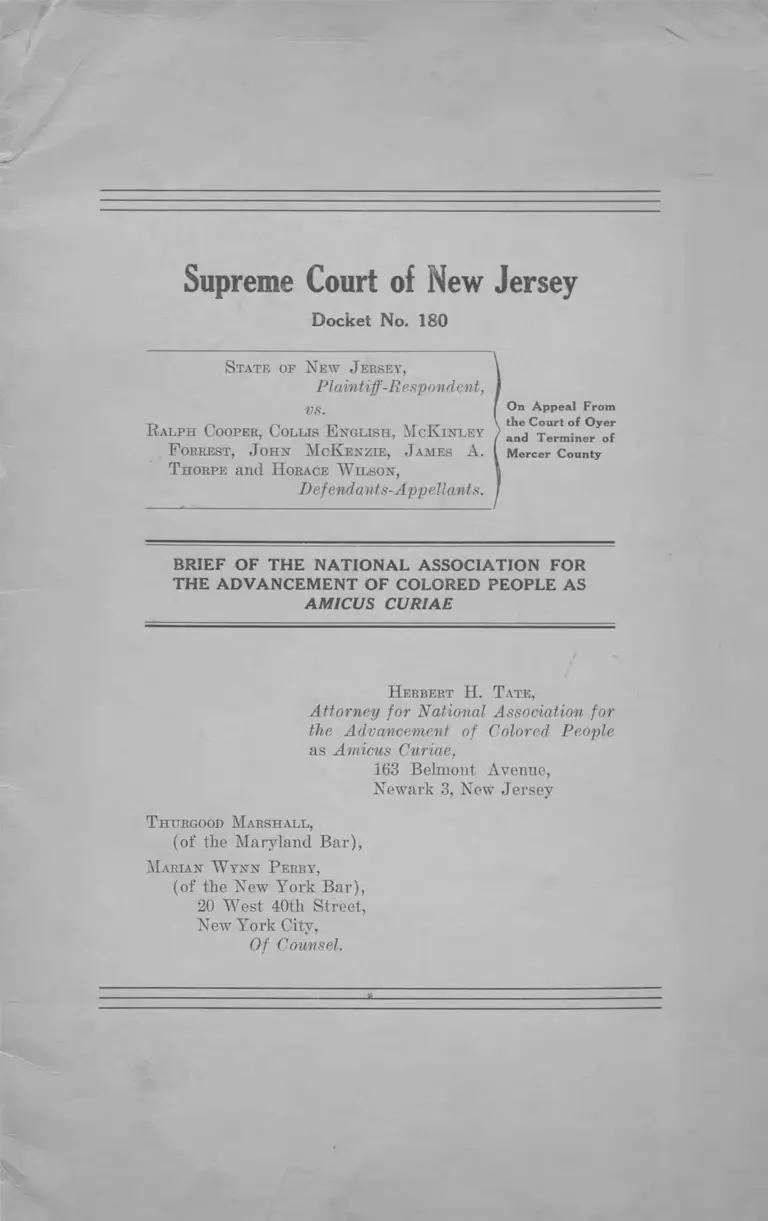

Supreme Court of New Jersey

Docket No. 180

S tate o f N ew J ersey , \

Plaintiff-Respondent, I

I O n A p p ea l From

R a l p h C ooper, C ollis E n g l ish , M cK in l e y \ In d ^ e rm in ^ o f

F orrest, J o h n M cK e n zie , J am es A. ( M ercer C ounty

T horpe and H orace W ilso n , a

Defendants-Appellants. J

BRIEF OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR

THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE AS

AMICUS CURIAE

H erbert H . T ate ,

Attorney for National Association for

the Advancement of Colored, People

as Amicus Curiae,

163 Belmont Avenue,

Newark 3, New Jersey

T hurgood M a r sh a ll ,

(of the Maryland Bar),

M arian W y n n P erry ,

(of the New York Bar),

20 West 40th Street,

New York City,

Of Counsel.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Statement of Interest of Amicus Curiae______ 1

Statement of Questions Involved___________ 2

Statement of the Case ____________________ 3

Statement of Facts _______________________ 3

A r g u m e n t :

I. The conviction of the defendants-ap-

pellants based upon the alleged confes

sions secured by force and duress, after

illegal arrest, during a long period of

detention is in violation of the 14th

Amendment to the United States Con

stitution ___________________ _____ _____ 4

II. The verdict is against the weight of the

evidence ____________________________ 15

Conclusion ____________________________ 19

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Cited

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U. S. 143____ __ _ 8

Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U. S. 278 ________ 11

Canty v. Alabama, 309 U. S. 629 ___________ 11

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227__ 4, 8, 9,11,12

Haley v. Ohio, 332 U. S. 596, 92 L. ed. Adv.

Op. 239 ___________ I____________________ 10,14

Lisenba v. California, 314 U. S. 219__________ 8, 9

Lomax v. Texas, 313 U. S. 544 ______ _______ 11

11

PAGE

Malinski v. New York, 324 U. S. 401........ „_8,12,13

McNabb v. U. S., 318 U. S. 332_____________ 14,15

Vernon v. Alabama, 313 U. S. 547 __________ 11

Ward v. Texas, 316 U. S. 547_______________ 9,10

White v. Texas, 310 U. S. 530 _____________ 11

Ziang Sung Wan v. U. S., 266 U. S. 1 _____ 11

Statutes Cited

New Jersey Rev. Stat. 1937, Sec. 2:216-9____ 14

United States Constitution, Amendment XIV 2

Authority Cited

President Hoover’s Commission on Law Ob

servance and Enforcement 14

The National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People is a membership organization

which for forty years has dedicated itself to work

ing for the broadening of democracy and securing

equal justice under the Constitution and laws of

the United States. The Association has more than

thirty branches in the State of New Jersey which

are joined together in a State Conference of

Branches for the promotion of their program.

From time to time some justiciable issue is pre

sented in the courts, upon the decision of which

depends the evolution of democratic institutions

for some vital area of our national life. The right

of a state to secure the conviction of defendants

upon confessions secured through duress is such

an issue, and one in the presentation of which the

Association has played an active role for many

years. The instant case presents that issue. For

these reasons the NAACP has requested and ob

tained leave of this Court to present this brief as

amicus curiae.

Statement of Interest of Amicus Curiae

Statement of the Questions Involved

1. Whether convictions secured by confessions

obtained from defendants arrested without war

rants and who were questioned almost continually

for more than four days in the presence of many

police officers, and who were not arraigned until

after the confessions were secured, who were

not advised of their constitutional rights and of

their privilege to remain silent, were secured

under such circumstances as to violate the Due

Process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of

the Constitution of the United States?

2. Whether the verdict of guilty was against

the weight of the evidence?

3

This is an appeal by writ of error to this Court

to review a conviction for murder in the Court

of Oyer and Terminer of the County of Mercer,

New Jersey rendered on August 6, 1948 on indict

ment No. 44 of the January Term of that Court,

upon which the petit jury found a verdict of guilty

and a sentence of death was imposed.

The writ of error was filed on August 20, 1948.

Statement of the Case

Statement of Facts

The defendants-appellants have been indicted,

tried and convicted of the murder of one William

Horner in Trenton on January 27, 1948. The six

defendants are Negroes and the deceased was a

white man. The record discloses that aside from

a highly dubious alleged identification of three of

the defendants, no evidence connecting any of

these defendants with crime was produced by the

State.

The record discloses further that four of the

five confessions secured were secured by fear and

intimidation during a long period of illegal deten

tion, constant questioning, confrontation by al

leged confederates and frequent accusations that

statements were “ lies” . The arrests of the de

fendants were illegal—flagrantly made without

warrants although there was ample time to secure

them.

4

A R G U M E N T

I.

The conviction of the defendants-appellants

based upon the alleged confessions secured by

force and duress, after illegal arrest, during a

long period of detention is in violation of the

14th Amendment to the United States Con

stitution.

In reviewing the conviction of these appellants

this Court is charged with grave responsibility.

The Supreme Court in Chambers v. Florida, 309

U. S. 227, reversing a conviction based on confes

sions induced by fear, reemphasized the challeng

ing role of our judiciary, stating:

“ Under our constitutional system, courts

stand against any winds that blow as havens

of refuge for those who might otherwise suf

fer because they are helpless, weak, outnum

bered, or because they are non-conforming

victims of prejudice and public excitement.

* * * No higher duty, no more solemn respon

sibility rests upon this Court than that of

translating into living law and maintain

ing these constitutional shields deliberately

planned and inscribed for the benefit of every

human being subject to our constitution of

whatever race, creed, or persuasion” (p. 241).

The convictions before this Court for review

are, like the convictions in the Chambers case,

based upon confessions secured from poor, humble

and ignorant persons in such manner as to make

“ the constitutional requirement of due process of

law a meaningless symbol” . 309 U. S. 240

5

In this record, the law enforcement officers and

the county prosecutor frankly admit that these

defendants were arrested without warrants, ille

gally detained far beyond the forty-eight hour

statutory limitation and subjected to repeated

questioning, confrontation of supposed confed

erates, awakened at all hours of the night and per

mitted no aid, comfort or counsel during a period

of 4 to 5 days. The police testified that they were

aware that any detention of a person beyond 48

hours without arraignment was illegal (R. 2438a).

The purpose of the illegal detention was openly

admitted by the Acting Captain of the police on

the witness stand:

“ We was investigating a high misdemeanor

and we had admissions by certain ones we had

under arrest and implicated the others. That’s

the reason we held them” (R. 2437a).

At the trial it became apparent that the prose

cutor and his assistants had been willing accom

plices in this illegal detention, if not the chief ad

vocates of it (R. 5758a).

This treatment was continued until the police

and the prosecutor had decided that it had pro

duced as much in the way of statements implicat

ing the defendants in the crime as was humanly

possible.

A brief statement of the treatment by police and

prosecutors which elicited these alleged confes

sions establishes their illegality.

Collis English : Arrested without warrant Feb

ruary 6, 1948 in his home at 8.30 p.m.

6

Questioned by three or more police officers who

admitted they did not advise him of his right to

remain silent (R. 457a, 497a, 536a).

Taken twice during night to Robbinsville at

midnight and again at 5 a.m. (R. 506a, 521a).

Questioned on February 7, 8, 9 and 10 in pres

ence of many officers, confronted with men who

had made statements implicating him (R. 244a,

245a, 972a, 1242a, 2452a, 2399a). Finally the

police testified they “ told him what part he played

in the crime” and he confessed (R. 991a, 992a).

After midnight on the 10th, he signed a confession.

Arraigned on the 11th.

Ralph Cooper: Arrested without warrant on

February 7 at 6.30 or 7.00 a.m. in nearby town,

handcuffed and brought to police station (R. 524a,

556a, 588a, 617a).

Questioned at length at all hours of day and

night by many officers February 8, 9 and 10. Taken

to store where crime was committed, confronted

with alleged confederates (R. 2398a, 2401a, 2409a).

February 10 made a “ satisfactory” statement to

police (R. 2409a). About 2.30 a.m. February 11

signed statement (R. 2421a). Arraigned Feb

ruary 11 (R. 2427a).

James Thorpe: Arrested February 7 at 5.00

p.m. without a warrant (R. 4792a and 4793a).

Questioned and confronted with alleged con

federates, 7th, 8th, 9th and 10th (R. 713a, 2400a,

2401a, 2404a). About midnight February 10th

signed statement (R. 2415a).

7

Police testified when asked by witness if state

ment was true he said “ No” and explained he was

signing it because he would get less time (R.

2415a).

Arraigned February 11. Visited by attorney

February 12.

McKinley Forrest: Arrested without warrant

on morning of February 7 at courthouse where he

went to see what he thought would be Collis Eng

lish’s trial on charge of auto theft (R. 1393a).

Questioned 7th and 8th and at 11.00 a.m. on 8th

saw his sister for a few minutes (R. 1397a). Ques

tioned and confronted with alleged confederates

on 9th and 10th. Police testified on 10th he

thought he heard his daughter’s voice, he sobbed

and moaned and a doctor was called to provide a

sedative (R. 2405a).

About midnight February 10th he signed his

initials to statement (R. 2417a).

Arraigned February 11th in morning (R.

2427a).

John McKenzie: Arrested without warrant

February 11th. Questioned and confronted by

alleged confederates but refused to make state

ment. Arraigned same day. Made statement on

February 12th after being confronted with Mrs.

Horner because of his fear of what Mrs. Horner

might charge him wTith (R. 2428a).

Of these defendants only Horace Wilson, a ma

ture man of 40, was able to withstand the pressure

of the questioning. Even he signed a statement

showing his utter confusion as to what days the

police were asking him about. He told truthfully

8

of his employment on Monday and Tuesday a week

after the murder (R. 3076a). At the trial he was

able to prove that he had worked there at the time

he mentioned and at another place on the days

concerning which the police meant to get a state

ment.

Under such circumstances, these alleged con

fessions were clearly inadmissible having been se

cured by fear produced by deliberate actions of

the police and the prosecutor in flagrant violation

of the due process of law. The Supreme Court

has in many cases held that even in the absence

of physical violence, confessions which are the

product of fear, are inadmissible.

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227;

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U. S. 143;

Malinski v. Neiv York, 324 U. S. 401.

In determining whether fear existed to such an

extent as to result in a “ deprivation of his free

choice to admit, to deny or to refuse to answer”

(Lisenba v. Cal., 314 U. S. 219, 241) the Supreme

Court has always considered “ the confessor’s

strength or weakness, whether he was educated or

illiterate, intelligent or moronic, well or ill, Avhite

or Negro” . (Opinion of Mr. Justice J ack so n ,

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U. S. 143, 162, dissent

ing from reversal of conviction of a white man.)

The Supreme Court has weighed as a factor in

reaching its decisions on the admissibility of con

fessions the following characteristics of defen

dants :

that they were “ ignorant, young, colored ten

ant farmers” Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S.

227, 238.

9

that they were ‘ ‘ interrogated by men who held

their very lives—so far as these ignorant

petitioners could know—in the balance” id.

p. 240.

that he was “ an ignorant Negro” — Ward v.

Texas, 316 U. S. 547, 555.

that they were “ ignorant and untutored per

sons in whose minds the power of officers was

greatly magnified” . Lisenba v. California,

314 U. S. 219, 239, 240.

Therefore this Court in determining the effect

upon the defendants of the actions of the police

and the prosecutor, must consider the prisoners

as individuals. All were Negroes. Three were

born and raised in Georgia, one in South Carolina

and one in North Carolina Only one was a native

of Trenton. Two of the defendants were com

pletely unable to read or write (R. 5252a, 2935a);

the others had little schooling. Less than one

month before his arrest James Thorpe had one

arm amputated (R. 4791a).

These are then the poor, the ignorant, the help

less, the weak and outnumbered for whom consti

tutional protections stand as a shield against that

exploitation which would otherwise be inevitable

under any system of government.

It is noteworthy that the outstanding Supreme

Court decisions invoking the protections of the

due process clause against convictions secured by

involuntary confessions have dealt almost exclu

sively with cases in which the defendants came

from the class to which these defendants also be

long. Early decisions dealt with more violent

forms of duress, yet, as Mr. Justice F ran k fu rter

V

10

said in his concurring opinion in Haley v. Ohio,

332 IT. S. 596, 92 L. ed. Adv. Op. 239:

“ It would disregard standards that we

cherish as part of our faith in the strength

and well-being of a rational, civilized society

to hold that a confession is ‘ voluntary’

simply because the confession is the product

of a sentient choice. ‘ Conduct under duress

involves a choice’, Union P. E. Co. v. Public

Service Commission, 248 U. S. 67, 70, 63 L. ed.

131,132, 39 S. Ct. 24, P u r . 1919B 315, and con

duct devoid of physical pressure but not

leaving a free exercise of choice is the product

of duress as much so as choice reflecting physi

cal eontraint” (p. 246).

Mr. Justice F r a n k f u r t e r recognized the dif

ficulty which faces a court reviewing a record such

as this in the absence of physical or intellectual

weights and measure “ by which judicial judg

ment can determine when pressures in securing

a conviction reach the coercive intensity that calls

for the exclusion of a statement so secured” . 92

L. ed. Adv. Op. 246. Even in the absence of such

weights and measures, however, the Supreme

Coui’t in Ward v. Texas, 316 U. S. 547 clearly

stated the standards by which it judged confes

sions to be illegally secured:

“ This Court has set aside convictions based

upon confessions extorted from ignorant per

sons who have been subjected to persistent and

protracted questioning, or who have been

threatened with mob violence or who have

been unlawfully held incommunicado Avithout

advice of friends or counsel, or who ha\Te been

taken at night to lonely and isolated places for

questioning. Any one of these grounds would

be sufficient cause for reversal” (p. 555).

11

citing:

Ziang Sung Wan v. United States, 266

U. S. 1, 14;

Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U. S. 278;

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227, 241;

Canty v. Alabama, 309 U. S. 629;

White v. Texas, 310 U. S. 530;

Lomax v. Texas, 313 U. S. 544;

Vernon v. Alabama, 313 U. S. 547.

It is clear that the alleged confessions of English,

Thorpe, Forrest and Cooper were secured by two

of the means proscribed in the Ward case—per

sistent and protracted questioning by police and

unlawful detention incommunicado.

Remembering that these defendants were sub

jected to protracted interrogations lasting into the

early hours of the morning while confined for four

days and questioned without formal charge, that

two were arrested without warrants in a small

farm tenant house, the decision of the Supreme

Court in Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227, con

tains a description of “ lawless means” which

most accurately describes the methods by which

these confessions were secured:

“ For five days petitioners were subjected to

interrogations culminating in Saturday’s

(May 20th) all night examination. Over a

period of five days they steadily refused to

confess and disclaimed any guilt. The very

circumstances surrounding their confinement

and their questioning without any formal

charges having been brought, were such as to

12

fill petitioners with terror and frightful mis

givings. Some were practical strangers in

the community; three were arrested in a one-

room farm tenant house which was their home;

the haunting fear of mob violence was around

them in an atmosphere charged with excite

ment and public indignation from virtually the

moment of their arrest until their eventual

confessions, they never knew just when any

one would be called back to the fourth floor

room and there, surrounded by his accusors

and others, interrogated by men who held

their very lives—so far as these ignorant peti

tioners could know—in the balance. The re

jection of petitioner Woodward’s first ‘ con

fession’, given in the early hours of Sunday

morning, because it was found wanting,

demonstrates the relentless tenacity which

‘ broke’ petitioners’ will and rendered them

helpless to resist their accusors further” (p.

240).

That the petitioners in the Chambers case were

ignorant and were Negroes, added weight to the

evidence that the confessions were involuntary.

So here the methods used by the police considered

in the light of the humble position of the defen

dants gives added weight to the charge that these

confessions were involuntary, produced by fear of

the power of the police.

Of this entire procedure the Supreme Court

said in the Chambers case “ To permit human lives

to be forfeited upon confessions thus obtained

would make of the constitutional requirements of

due process of law a meaningless symbol” (p.

242).

More recently in Malinski v. New York, 324 U. S.

401, the Supreme Court viewed with suspicion a

13

confession where the illegal detention was of

shorter duration—3 days—and the questioning

was not particularly protracted, yet the purpose of

the illegal detention and the confrontation of Ma-

linski with his alleged confederates was precisely

to create a state of mind in which a confession

would be secured. Adding to that suspicion, the

statement of the prosecutor in his summation that

“ ‘ Malinski was not hard to break’ ; that ‘ he did

not care what he did, he knew the cops were going

to break him down’ ” (p. 407), the Supreme Court

concluded “ If we take the prosecutor at his word,

the confession of October 23 was the product o f

fear—one on which we could not permit a person

to stand convicted of a crime” (p. 407).

Again there is a striking similarity to the Tren

ton case for the prosecutor there in his summation

spelled out the psychological terror by which these

confessions were induced—by which these men

were “ broken” :

“ We had a lead on the murder. The police

were on the move to protect your lives. * * *

They worked four continuous nights, no sleep,

* * * They got the lead * * * (R. 5757a).

“ Remember the police now had the wedge in

this case. Why, it ’s common sense; what hap

pens ; You have one man who has made an ad

mission of his participation in the crime, you

confront him with another one, and you try

to show him you know about this, that he was

in it. What happened? Cooper broke. So

you use the two to confront a third man. So

they figure these two men have admited their

participation, I guess I ’m next. And that’s

the way the six of them—except that McKen

zie did not come in until much later” (R.

5758a).

14

Again, in the Haley ease, supra, Mr. Justice

F r a n k f u r t e r ' s concurring opinion gives weight to

the fact that the securing of a confession “ was the

very purpose” of the police procedure, stating:

“ Of course, the police meant to exercise pres

sures upon Haley to make him talk” (p. 246).

This Court is called upon to invoke on behalf of

these helpless defendants the constitutional pro

tection intended to prevent the police from “ using

private secret custody of either man or child as

a device for wringing confession from them.”

Haley v. Ohio, supra, p. 243. Although during the

conduct of the trial every effort was made to im

press upon the jury the need to uphold the police

in the methods used in order to maintain respect

for law enforcement, no such consideration is pos

sible or necessary as a justification for methods

proscribed by the constitution.

Our society condemns the secret protracted

questioning of suspects by the police. President

Hoover’s National Commission on Law Observance

and Enforcement found that the abuse of police

power under such circumstances was actual and

extensive, but even more important the report of

that Commission found that the tolerance of such

methods was not necessary nor desirable for the

suppression of crime. As the Supreme Court said

in McNahh v. U. S., 318 U. S. 332, there exists an

impressive list of state statutes requiring that ar

rested persons be promptly taken before the com

mitting authority, including New Jersey Rev. Stat.

1937, Sec. 2 :216-9. Analyzing the pui'pose of this

legislation, the Supreme Court found it inherent

15

in a democratic society, which respects the dignity

of all men, as a safeguard against the misuse of

the law enforcement process, and there said:

“ Zeal in tracking down crime is not in itself

an assurance of soberness of judgment. Dis

interestedness in law enforcement does not

alone prevent disregard of cherished liberties.

Experience has therefore counseled that safe

guards must be provided against the dangers

of the overzealous as well as the despotic.

The lawful instruments of the criminal law

cannot be entrusted to a single functionary.

* * * Legislation such as this, requiring that

the police must with reasonable promptness

show7 legal cause for detaining arrested per

sons, constitutes an important safeguard—

not only in assuring protection for the inno

cent but also in securing conviction of the

guilty by methods that commend themselves

to a progressive and self-confident society.

* * * It reflects not a sentimental but a sturdy

view of law enforcement. It outlaws easy

but self-defeating ways in which brutality is

substituted for brains as an instrument of

crime detection” (p. 344).

The violation of due process here is so flagrant

that the admission of these fear induced confes

sions was a clear denial of due process of law call

ing for a reversal of the conviction by this Court.

II.

The verdict is against the weight of the

evidence.

The sixteen volume record in this case is a

monument to confusion—not because the issues

are unclear or the testimony technical, but because

the simple, untutored defendants were subjected to

16

“ tricky” cross examination and testimony of

every witness was so lengthened and repetitious as

to be confusing even on second and third reading.

Throughout the record there shine two aspects

of the trial—one that the Negro in Trenton was

treated as he would have been in the South—and

the other that the trial was perverted from a

search for the truth into a search for support for

the prestige of the police of Trenton.

The prosecution has sought to make much of the

fact that these men did not insist upon constitu

tional rights at the time of their arrest and illegal

detention. Speaking of the police invasion of Wil

son’s home for the purpose of arresting Wilson

and Cooper without a warrant the prosecutor asks

why both these men were found in bed in the early

hours of the morning and he states “ An innocent

man doesn’t react that way. An innocent man

would have stood up and said ‘ What right have

you to be here’ ” (R. 5741a). This Court should

remember that these were second class citizens.

These were not persons who from their infancy

have been taught their right to stand up as an

equal of a white man—much less white policemen.

Alleged “ confessions’ aside, the evidence

amounts to nothing. No jury could be free of a

reasonable doubt.

Without the confessions, the state’s case is as

follows:

Elisabeth McGuire Horner ivho lived with de

ceased :

On January 16 a Negro went into the second

hand store and looked at a mattress. The store

17

is in a neighborhood immediately contiguous to

Ihe main “ black ghetto” in which Trenton’s

Negroes are forced to live. On January 20, two

other Negroes came in and paid $2.00 deposit on a

mattress and got a receipt (E. 237a, 239a).

On January 26, two Negroes came back and one

said he wanted the deposit back. The Negro identi

fied as McKinley Forrest signed a receipt (R.

241a).

On January 27 three Negroes came in to the

store and two went back to see the mattress again,

and two went into the back room and one remained

in front with the witness. This witness was hit

on the head and lost consciousness and some time

later the body of the deceased was found (R. 247a-

252a). In his pocket was a roll of bills containing

$1,570 (R. 453a).

Frank Eldracher:

His car was parked near the store. He saw two

Negroes, one tall and dark, one short and light,

come out of store calmly, close door, walk down

the street. Then door opened and Elizabeth Mc

Guire Horner called for help—with blood on her

face (R. 359a).

Police Officer Dennis:

Found two bottles of “ step up” in store—one

broken, one near body (R. 351a and 353a).

A. Kokenakis:

Has store in Negro neighborhood; sold two

bottles of “ step up” to Negroes the day of the

murder (R. 440a-446a).

18

Two people, according to this evidence saw men

who might have been the assailants. But only one

identified any of them, and that identification was

most flimsy. For although Elizabeth McGuire

Horner claimed to have seen two Negro men con

cerned with the murder on two successive days,

yet two weeks after the murder, when she saw the

defendants at the police station, she was unable to

identify them (R. 277a). She testified she later

recognized four of the defendants from photo

graphs furnished by Police (R. 278a-283a). At the

trial however, she identified one defendant (Ralph

Cooper) as the man who came in to look at a mat

tress January 16, two defendants (McKinley For

rest and Collis English) as having come in three

times, once to pay a deposit, six days later to get

the deposit back, without question, and the third

time the day of the murder, and the fourth de

fendant (Hoi’ace Wilson) as having come in on

the day of the murder and discussed with her the

purchase of a stove. Having had such knowledge

of the men she could not identify them face to

face shortly after their arrest. Her memory had

to be refreshed with photographs of the accused

men taken by the police. Surely this is a most

unsatisfactory—in fact incredible—identification.

Particular doubt is cast upon the identification of

McKinley Forrest by the fact that Mrs. Horner

definitely said he was the one who signed a re

ceipt in a false name. There was uncontroverted

evidence that McKinley Forrest is illiterate, un

able even to sign his own name (R. 5252a).

The other witness, who saw two Negroes come

out of the store, Mr. Eldracher, did not identify

any of the defendants as the men he saw.

19

Even assuming that the two bottles of “ step

up” had been connected with the crime, the woman

who sold two bottles of “ step up” to two Negroes

did not recognize any of the defendants and did

not connect them in any way with the crime.

John McKenzie was not connected with the

crime by any witness and Ralph Cooper’s only

connection with the scene of the crime was Eliza

beth McGuire Horner’s testimony that ten days

before the crime he looked at a mattress in the

store.

That any person should lose his life in the elec

tric chair by such flimsy evidence would strike a

blow at the roots of justice. That six Negroes

should die when only the most questionable iden

tification connecting them with the crime has

been made of three intensifies the injustice and

heightens the danger to justice.

Conclusion

It is therefore respectfully submitted

that the conviction of these defendants

in the Court below should be reversed.

H erbert H . T ate ,

Attorney for National Association

for the Advancement of Colored

People as Amicus Curiae.

T hurgood M a r sh a ll ,

(of the Maryland Bar)

M arian W y n n P erry ,

(of the New York Bar)

Of Counsel.

L a w y e r s P ress, I nc., 165 William St., N. Y. C. 7; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300