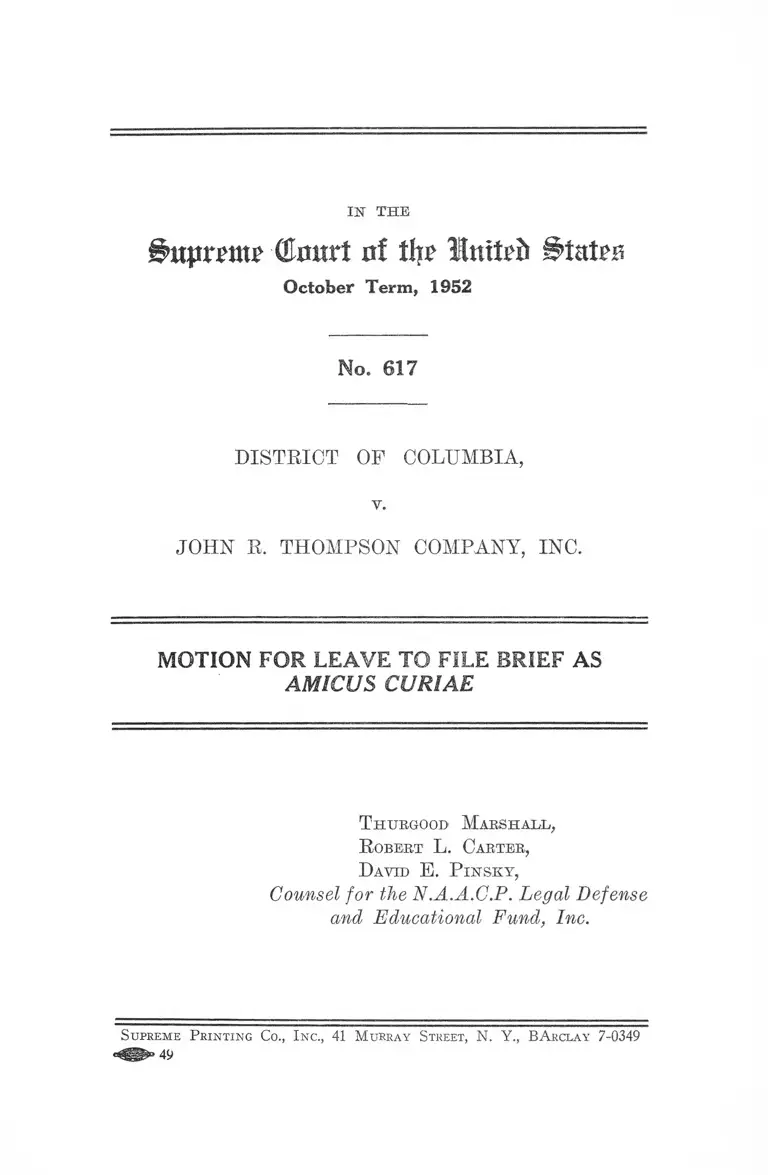

District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Company Motion for Leave to File Brief as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1952

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Company Motion for Leave to File Brief as Amicus Curiae, 1952. 2b9507f5-af9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/40c20774-3d37-4833-aaf5-4ca48fa79dd5/district-of-columbia-v-john-r-thompson-company-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Copied!

1ST THE

^upmtu' (tort at tip Imtefr &tnP$

October Term, 1952

No. 617

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA,

JOHN R. THOMPSON COMPANY, INC.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AS

AMICUS CURIAE

T hurgood Marshall,

R obert L. Carter,

D avid E. P iktskt,

Counsel for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.

Supreme Printing Co., Inc., 41 M urray Street, N. Y., BArclay 7-0349

IN TH E

Supreme ( ta r t nf tfje IntteS I to ta

October Term, 1952

No. 617

-----------------------------------------------------o — ----------------------------- -— —

D istrict of Columbia,

v.

J ohn R. T hompson Company, I nc.

-------- --------------------- o-----------------------------

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AS

AMICUS CURIAE

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice of the

United States cmd the Associate Justices

of the Supreme Court of the United States:

The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., pursuant to Rule 27 of the Rules of the Supreme Court

of the United States, moves for leave to file a brief as

amicus curiae in the case of District of Columbia v. John

R. Thompson Company, Inc., No. 617 in this Court,

I. Consent to file such brief has been requested of the

parties. The District of Columbia granted consent. The

John R. Thompson Company, Inc., has refused consent.

II. Movant is a national organization engaged in com

batting racial discrimination in the United States. One

of its principal purposes is to secure judicial recognition

and enforcement of federal, state and local enactments

prohibiting discrimination based on race or color.

Each of the 280,000 Negroes residing in the District of

Columbia has a direct personal stake in the outcome of

2

this case. The Equal Service Acts of 1872 and 1873 gave

all persons the right to receive the essential public services

provided by hotels, restaurants, barber shops and other

places of public accommodation without discrimination on

account of race or color. If the decision of the court below

invalidating these Acts is upheld, Negro residents par

ticularly will lose vital and precious personal rights.

The impact of this decision on Negroes residing outside

the District of Columbia will be equally as great. The

District of Columbia, the seat of our government, attracts

innumerable visitors who come to observe the processes

of democratic government in action and to see the monu

ments and memorials which symbolize our history. As

travellers, they are dependent on hotels and restaurants for

lodging and food. Unless they can be assured such essen

tial services, their privileges as citizens to visit the seat

of our government will continue to be seriously abridged.

As vital as the direct effect of this decision will be, its

indirect repercussions will be even more significant. The

District of Columbia symbolizes American democracy. So

long as racial discrimination in places of public accommoda

tion is sanctioned by law in the heart of the nation, efforts

to eliminate it in other areas will necessarily encounter

stiff resistance. Once it is clear, however, that racial

discrimination in our capital has no legal warrant, the

great mass of national opinion seeking to eliminate racial

barriers will be swelled with new moral strength and vigor.

Thus, the elimination of racial discrimination in places of

public accommodation in the District of Columbia is

especially significant to America’s progress toward full

equality for all persons.

III. Movant has not seen the briefs on the merits in this

Court and it is of the opinion that these have not yet been

.submitted. However, it does not believe that the follow

ing questions of law will be adequately presented.

3

A. Movant does not believe that the parties, in dealing

with the law with respect to municipal corporations, will

give sufficient attention to the public policy considerations

which favor local governmental effort toward the elimina

tion of racial discrimination and the broad national policy

against racial discrimination.

1. The power of local communities to deal with the

problems of racial discrimination on a local level is ren

dered extremely questionable in the light of the decision

of the Court of Appeals. Until now the validity of local

enactments in the field of civil rights has never been seri

ously questioned. In recent years, many communities have

attempted to deal with various facets of racial discrimina

tion by the enactment of local ordinances. Fair employ

ment practice ordinances are now in effect in Chicago,

Minneapolis, Cleveland, Youngstown, Philadelphia, Mil

waukee, and many other cities, thus insuring to hundreds

of thousands of Negroes the right to be free from discrimi

nation in employment. The validity of these ordinances

has suddenly become suspect in the light of decision of the

Court of Appeals. While their legality is a matter of state

law, the decision of the court below stands as a formidable

precedent. Moreover, the status of territorial acts enacted

in Alaska, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands prohibiting

racial discrimination in places of public accommodation

now becomes uncertain. If this decision stands, much of the

substantial grass roots progress in eliminating racial dis

crimination will be seriously imperiled.

2. In deciding that the Legislative Assembly for the

District of Columbia had no power to enact the Equal

Service Acts of 1872 and 1873, the Court below distinguished

the authorities which hold that ordinances requiring segre

gation are within the bounds of municipal power. This

distinction is predicated on the ground that such ordinances

are in accord with custom and, hence, necessary to the

preservation of peace and order. Movant believes that

4

this rationale is unsound and extremely prejudicial to the

rights of all minorities, for local custom may often be in

conflict with the rights of a minority and even the public

policy of the state at large.

The theory of the Court below imports into the law of

municipal corporations a new and confusing doctrine. If

it prevails, the validity of anti-discrimination ordinances

may depend on a factual determination as to whether they

are in accord or in conflict with local custom. Movant does

not believe that the full effect of this theory on civil rights

generally will be adequately explored by the parties. More

over, movant does not believe that the parties will give

adequate consideration to the broad national policy against

racial discrimination of every kind.

B. A majority of the Court of Appeals did not concur

in the opinion of Chief Judge Stephens. As a result, the

separate concurring opinion of Judge Prettyman takes on

added significance. The position of Judge Prettyman is

that, assuming the Legislative Assembly had the power to

enact the Equal Service Acts, they were, in effect, munici

pal ordinances which have now lost all force and effect

through abandonment and non-user. Ordinances and stat

utes protecting minority rights may often be frustrated by

apathy or even hostility on the part of some law enforce

ment officials. Under the theory set forth in the concurring

opinion below, such prolonged apathy or hostility may

result in nullification of the enactment.

Movant does not believe that the impact of this doctrine

on the rights of Negroes generally and its total ramifica

tions will be fully presented. And it does not believe that

the parties, in dealing with this issue, will give adequate

consideration to the broad national policy against racial

discriminaton of every kind.

5

IV. Movant submits that the above considerations are

relevant to the issues at the bar and to the particular hold

ing which may emanate from this Court.

W herefore movant moves for leave to file a brief herein

as amicus curiae.

Respectfully submitted,

T hurgood Marshall,

R obert I j . Carter,

David E. Pin sk y.

Counsel for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.