Biggers v. Tennessee Petition for Rehearing

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Biggers v. Tennessee Petition for Rehearing, 1967. d496b4d8-c69a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/40ea1192-78ac-42a6-9fb8-19a1e08f55ec/biggers-v-tennessee-petition-for-rehearing. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

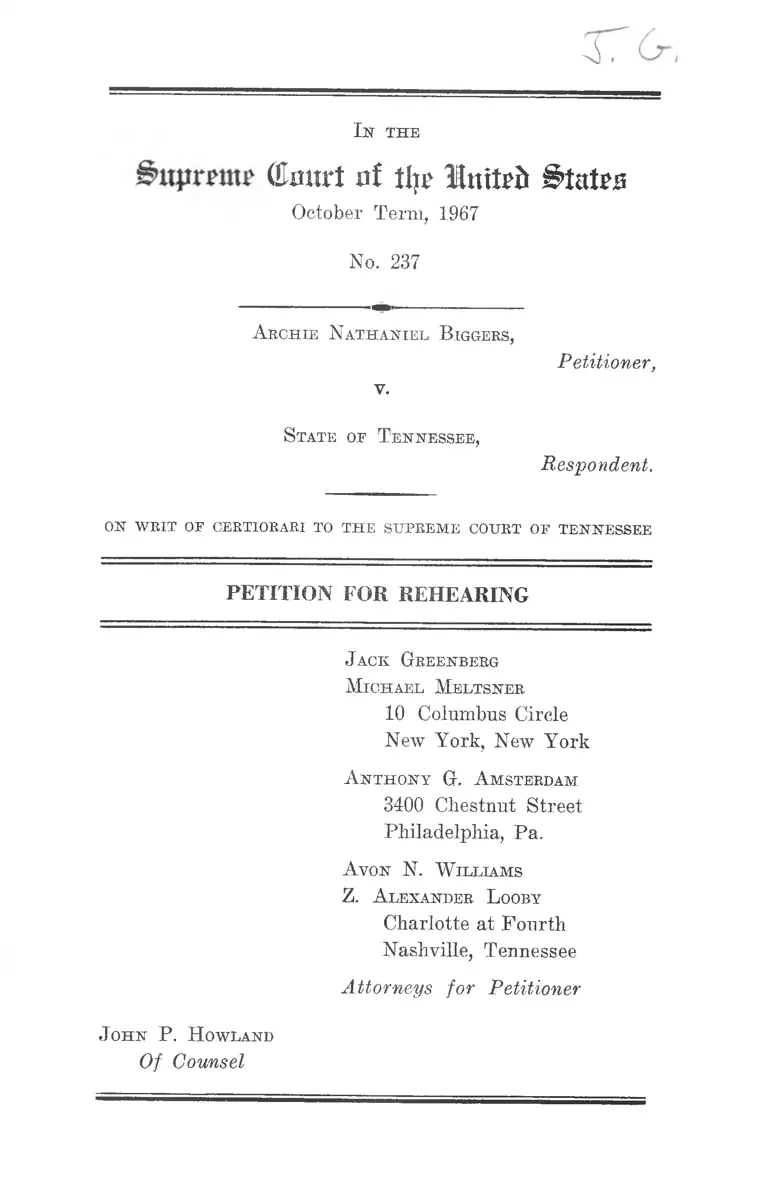

I n the

(Emtrt nf % Itttfpd &tatp,a

October Term, 1967

No. 237

Archie Nathaniel B iggers,

v.

Petitioner,

State of Tennessee,

Respondent.

ON W R IT OF CERTIO RA RI TO T H E S U P R E M E COU RT O F T E N N E S S E E

PETITION FOR REHEARING

J ack Greenberg

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New Y7ork

Anthony G. Amsterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa.

Avon N. W illiams

Z. Alexander L ooby

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioner

J ohn P. H owland

Of Counsel

I n t h e

g>H|tr£m£ (to rt at tfyp States

October Term, 1967

No. 237

Archie Nathaniel Diggers,

v.

Petitioner,

State of Tennessee,

Respondent.

ON W R IT OF CERTIO RARI TO T H E S U P R E M E COU RT O F T E N N E S S E E

PETITION FOR REHEARING

Petitioner prays that the Court grant rehearing of its

March 18, 1968 decision affirming, by an equally divided

Court, petitioner’s conviction and sentence to twenty years

in prison.

R easons for Granting Rehearing

I

Subsequent to the Court’s ruling in petitioner’s case,

certiorari has been granted to consider, in the case of

another state prisoner, those circumstances which result

in an identification procedure violating the Due Process

2

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, Foster v. California,

No. 638 Misc., 36 U. S. L. Week 3374 (3/25/68). Foster

involves a lineup which is alleged to have been unconstitu

tionally conducted. As petitioner was not accorded the ele

mentary protection of a lineup—and the record is barren

of evidence justifying the failure to hold one—reversal in

Foster would, a fortiori, affect, if not determine, final

resolution of petitioner’s constitutional claim. An interven

ing circumstance such as “the fact that the same or a

related issue has come before the court in other cases

still pending” is a common ground for grant of rehear

ing. Stern and Gtressman, Supreme Court Practice, 3rd

Ed. 389; see Pickett v. Union Terminal Co., 313 U. S. 591

(1941); 314 U. S. 704 (1941); 315 U. S. 386, 389, 394 (1942).

It is plainly appropriate and just that the results in these

two cases conform. Unless it is beyond doubt that princi

ples announced in Foster will not bear upon petitioner’s

claim, this petition should be granted.

That affirmance is the product of an equally divided

Court further supports granting of this petition. The

Court has granted rehearing most often in cases such as

this where it could not, initially, agree on a decision. Stern

and Gressman, supra, at 387. The present result works

a harsh penalty on a minor without articulate decision of,

or agreement as to, two substantial federal claims. It

may be that over the years some few men will have to

go to prison because this Court may upon occasion be

unable to reach a decision, but such a manner of reaching

a result has always been avoided except where absolutely

necessary and it is not absolutely necessary where re

view has been granted with respect to what may be a con

trolling principle of law.

3

II

The Court in Simmons v. United States, No. 55, 0. T. 1967 re

affirmed the approval of Palmer v. Peyton, 359 F. 2d 199 (4th Cir.,

1966), given in Stovall v. Denno, 388 U. S. 293, 301, 302 (1967). Peti

tioner submits that the facts of his case are simply not sufficiently

distinguishable from Palmer to support a difference in result:

Critical

Circumstances Palmer Biggers

Gap between crime

and identification

1 day 7 months

Time during which

victim could observe

criminal

15-30 minutes 10-30 minutes

Initial opportunity to

observe

a s s a i l a n t ’s head

covered by paper bag

opportunity limited

by darkness

Voice identification spoke words used by

assailant

spoke words used by

assailant

Physical identifica

tion

none attempted yes

Lineup none none

Justification for no

lineup

none none

Evidence corroborat

ing guilt

assailant was wear

ing an orange shirt

and Palmer was wear

ing a similar shirt

when arrested; wit

ness stated that Palm-

none: an eyewitness

failed to identify Big

gers

er confessed to the

crime

4

Significantly, recent decisions of the New York Court

of Appeals and the California Supreme Court read Palmer

and Stovall v. Denno, supra, in a way which would require

a reversal here, and which suggest (when the grant of

certiorari in Foster is considered) that Archie Nathaniel

Biggers may, fortuitously, be only the hapless victim of a

short-lived restrictive interpretation of the due process

obligation of the states to provide for fair identification

procedures. In State v. Ballott, 233 N. E. 2d 103 (1967)

for example, the facts surrounding the identification are

strikingly similar to petitioner’s case:

Miriam Seidman and Rose Scipone worked for the

M. N. Axim Lumber Company in Queens County. It

was the task of those employees, each Friday, to drive

to the bank and pick up the company payroll of about

$5,000 and then return to the company’s offices with

the money in an envelope. On the Friday in question,

January 18, 1963, as they were about to alight from

their car, a Negro, wearing a hat and a heavy over

coat, with turned up collar, appeared at the window

and demanded the envelope, threatening to shoot if it

was not turned over to him. Frightened, Mrs. Seidman

handed him the envelope and Mrs. Scipone gave him

her purse containing $27. The robber then fled.

The defendant was arrested a year later, having

been implicated in the robbery by a man named Doyle.

The latter, questioned a short time after the robbery,

declared that, having learned of the payroll procedure

from one of the lumber company’s employees, he and

the defendant Ballott had planned the commission

of the crime. Doyle pleaded guilty to conspiracy to

commit larceny, a misdemeanor, and subsequently

testified against the defendant.

5

Mrs. Scipone testified upon the trial that she had

not seen the face of the robber and only Mrs. Seidman

identified the defendant as the man who had held them

up. It was disclosed, during the course of her testi

mony, that in January, 1964, a year after the robbery,

the police had exhibited to her the defendant, alone

in a room in the station house, and that she had then

stated that he was the person who committed the rob

bery. It also appeared that she had identified the

defendant only after he had, at her request, donned a

hat and a heavy coat—similar to those worn by the

robber—and uttered the words—somewhat like those

spoken—“give me the money, give me the envelope.”

Mrs. Seidman acknowledged that she made her iden

tification only after she had heard the defendant speak.

In the California case, the court reversed the conviction

even though a lineup was held, People v. Caruso, -----Cal.

2d ----- , 2 Crim. L. Rptr. 3135 (1/26/68) :

But the uncontradicted testimony of all those who

viewed the lineup demonstrates that it was conducted

under circumstances which could only have suggested

to Butkus and Seeley that defendant was the man to

be charged with the offense. Defendant is of imposing

stature, being 6 feet 1 inch tall, and weighing 238

pounds. He is of Italian descent, with a very dark

complexion, and has dark wavy hair. The two vic

tims, the officer in charge of the investigation, Sergeant

Allen, and defendant all testified that the other line

up participants did not physically resemble defendant.

They were not his size, not one had his dark com

plexion, and none had dark wavy hair. During the

robbery both Seeley and Butkus had noted the driver’s

6

large size and dark complexion, and, if they were to

choose anyone in the lineup, defendant was singularly

marked for identification. We can only conclude that

the lineup was “unnecessarily suggestive and con

ducive to irreparable mistaken identification” (Stovall

v. Denno (1967) supra, 388 U. S. 293, 302), and we hold

that its grossly unfair makeup deprived defendant of

due process of law. (Stovall v. Denno, supra).

Of course, nothing decided in these cases binds this

Court. But the ready, and we submit convincing, applica

tion of Stovall by the highest courts of New York and Cali

fornia supports a serious re-examination of petitioner’s

claim. While this Court’s precedents are not always capable

of mechanical application to subsequent cases, surely it is

no accident that both state courts have applied Stovall to

identification procedures which under no reasonable con

struction were significantly more likely to produce “irrep

arable mistaken identification” than those employed by

the Nashville police to suggest the guilt of a sixteen year

old boy.

In addition, as the Supreme Court of California found

in People v. Caruso, supra, the due process infirmity of

suggestive identification procedures is enhanced where

the record shows a serious doubt as to the reliability of the

judgment of guilt. In State v. Ballott, supra, and Palmer v.

Peyton, supra, there was independent evidence connect

ing the defendants with the crime; in Biggers’ case, how

ever, a questionable identification of one with no criminal

record stands uncorroborated. The state, moreover, treated

the jury in a manner which substantially impaired its

capacity to appraise that identification objectively: news

papers were used as a forum for grossly prejudicial com

ment on the case (R. 196, 197); then the jury selected

7

from those exposed to the papers was reminded of the

harmful stories by the prosecution on voir dire (R. 58, 59,

175, 215) and at trial (B. 17); police officers were permitted

to testify again and again to the facts of identification

although they were not controverted; finally, the jury was

subjected to a summation which the Supreme Court of

Tennessee characterized as “appealing to racial prejudice”

and which the court found to be error—but non-reversible

(R. 183, 209, 210). Petitioner respectfully submits that

an uncorroborated identification so frail requires a guilt

finding process of greater integrity than shown by this

record.

CONCLUSION

For the forego ing reasons petitioner requests that the

Court grant rehearing and reverse the judgm ent below .

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Anthony G. Amsterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa.

Avon N. W illiams

Z. Alexander L ooby

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioner

J ohn P. H owland

Of Counsel

8

Certificate

I, Michael Meltsner, a member of the Bar of this Court

and counsel for petitioner herein, hereby certify that the

foregoing Petition for Rehearing is presented in good

faith and not for purposes of delay.

Attorney for Petitioner

RECORD PRESS — N. Y. C. 38