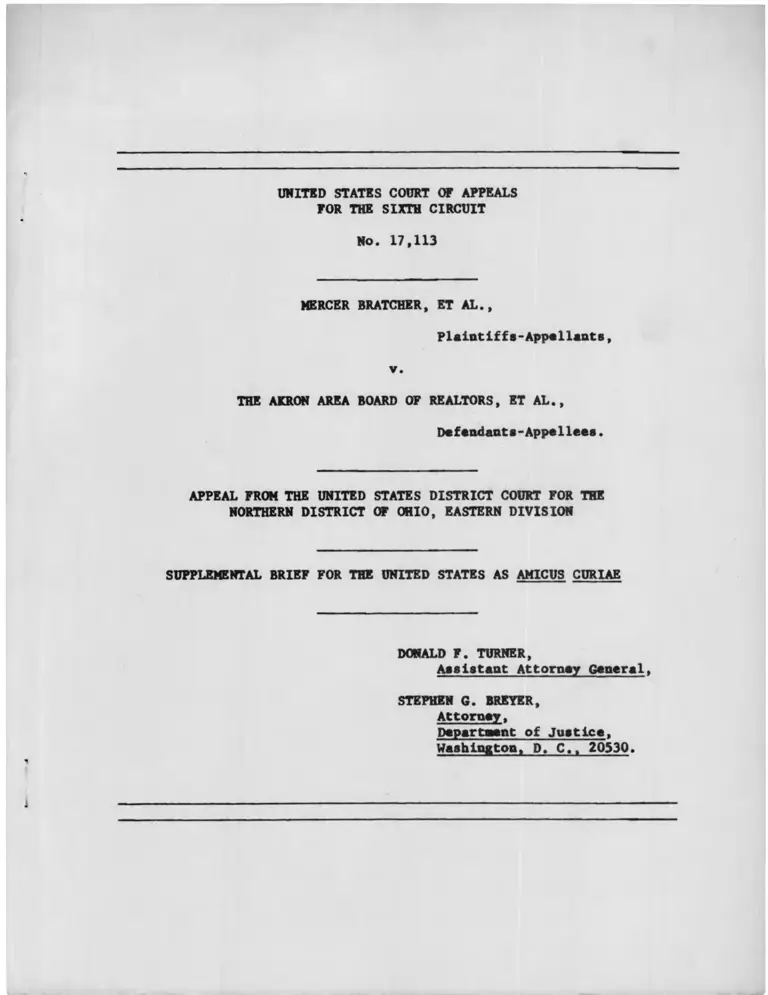

Bratcher v. Akron Area Board of Realtors Supplemental Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

March 10, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bratcher v. Akron Area Board of Realtors Supplemental Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, 1967. 49399732-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/40ea477b-7d49-4430-8516-857cf7dc825c/bratcher-v-akron-area-board-of-realtors-supplemental-brief-for-the-united-states-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 17,113

MERCER BRATCHER, ET AL.,

Plaintiffs-Appallants,

v.

THE AKRON AREA BOARD OF REALTORS, ET AL.,

Dafandants-Appalleas.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF OHIO, EASTERN DIVISION

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

DONALD F. TURNER,

Assistant Attornay General,

STEPHEN G. BREYER,

Attornay.

Daparftnt of justice,

Washington, D. C., 20530.

I N D E X

Page

Interest of the United States .................................... 1

Supplemental brief for the United States as amicus curiae . . . . 2

CITATIONS

Cases:

Apex Hosiery Co. v. Leader, 310 U.S. 469 ................... 6

Atlantic City Electric Co. v. General Electric Co.. 226 F.

Supp. 5 9 .............................................. 5

Bookout v. Shine Chain Theaters, Inc.. 253 F. 2d 292 . . . . 9

Brown Shoe Co. v. United States. 370 U.S. 294 ............. 6

Centonni v. T. Smith & Son. 216 F. Supp. 330 ............... 9

Chattanooga Foundry & Pipe Works v. City of Atlanta. 203 U.S.

390 ..................................................... 4, 7

Comaonwealth Edison v. AllIs-Chalmers Mfg. Co. 335 F. 2d 203 7, 8

Conference of Studio Unions v. Loew's Inc.. 193 F. 2d 51 . . 9

Continental Ore Co. v. Union Carbide & Carbon Corp., 370 U.S.

690 ..................................................... 10

Feddersen Motors, Inc, v. Ward. 180 F. 2d 5 1 9 ............. 6

Georgia v. Evans. 316 U.S. 1 5 9 .............................. 4, 7

Gomberg v. Midvale Co.. 157 F. Supp. 1 3 2 ................... 9

Hanover Shoe Inc. v. United Shoe Machinery Corp.. 185 F.

Supp. 826, affirmed 281 F. 2d 481, cert, denied 364 U.S.

9 0 1 ..................................................... 7, 8

Leh v. General Petroleum Corp.. 382 U.S. 5 4 ............... 5

Louisiana Petroleum Retail Dealers, Inc, v. Texas Co.. 148

F. Supp. 334 .......................................... 3

Mandeville Is1And Farms, Inc, v. American Crystal Sugar Co..

334 U.S. 2 1 9 .......................................... 4, 7

Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing Co. v. New Jersey Wood

Finishing Co.. 381 U.S. 3 1 1 ............................ 5

Nagler v. Admiral Corp.. 248 F. 2d 3 1 9 ...................... 11

Noerr Motor Freight. Inc, v. Eastern Railroad Presidents

Conference. 113 F. Supp. 737 ......................... 11

Package Closure Corp. v. Sealright Co.. 141 F. 2d 972 . . . 11

Radovich v. National Football League. 352 U.S. 445 ........ 5, 10

Cases [Continued]: Page

Rossi v. McCloskey & Co., 149 F. Supp. 638 ................. 9

Schulman v. Burlington Industries, Inc., 255 F. Supp. 847 . 9, 10

Snow Crest Beverages. Inc, v. Recipe Foods. Inc.. 147 F. Supp.

907 ........................................................ 9

South Carolina Council of Milk Producers. Inc, v. Newton, 360

F. 2d 4 1 4 ................................................. 9

State of Illinois v. Brunswick Corp., 32 F.R.D. 453 . . . . 8

State of Missouri v. Stupp Bros. Bridge & Iron Co., 248 F.

Supp. 1 6 9 ................................................. 7

Streiffer v. Seafarers Seachest Corp., 162 F. Supp. 602 . . 7

Thomsen v. Kayser, 243 U.S. 6 6 .................................. 4, 7

United States v. Borden Co., 347 U.S. 5 1 4 ...................... 3, 8

Statutes:

Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. 15, et seq.j

Section 4 ............................................... 3, 5, 6

Section 1 6 ............................................ 2, 5, 6

Miscellaneous:

Clark: "The Treble Damage Bonanza: New Doctrines of Damages

in Private Antitrust Suits," 52 Mich. L. Rev. 363 . . . 8

Note, 64 Columb. L. Rev. 570 ( 1 9 6 4 ) ....................... 6

u n i t e d sta tes c o u r t of a p p eals

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Ho. 17,113

MERCER BRATCHER, ET AL., APPELLANTS

v.

THE AKRON AREA BOARD OF REALTORS, ET AL., APPELLEES

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF OHIO, EASTERN DIVISION

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES

Th« United States wishes to file this suppleaental brief aaicus

curias in support of appellants because it believes that the arguments

aada In Defendants' Brief are erroneous and believes that their

acceptance by this Court would interefere with efficient antitrust law

enforceaant.

_1/ "Defendants' Brief" refers to the Brief on Behalf of All Defendant

Appellees Except First National Bank of Akron and Herberlch-Hall-Harter Inc.

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

Appellants have brought this suit on behalf of (1) Negroes wishing

to buy or rent houses in white neighborhoods in Akron, (2) white hone

owners who wish to sell or rent such houses to Negroes, and (3) Negro

real estate dealers who wish to belong to the Akron Area Board of Realtors.

The Conplaint charges that nambers of the defendant board of realtors

have agreed not to sell houses in white neighborhoods to Negro custoawrs

and to exclude Negro real estate dealers fron their board. Defendants

claim that none of the three gremps of persons that plaintiffs represent

has standing to sue. The Government submits that— to the contrary— all

three groups have standing.

Appellants are bringing this suit, which asks for an injunction,

_2/

under Section 16 of the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. 26. They have standing

to sue if they meet the requirements of that section by alleging facts

which show (1) that they personally are "threatened" with "loss or damage,"

(2) that the activity threatening them violates the antitrust laws, and

(3) that they are entitled to an injunction under traditional principles

2/ Section 16 provides in relevant part: "Any person . . . shall be

entitled to sue for and have injunctive relief . . . against threatened

loss or damage by a violation of the antitrust laws . . . when and under

the same conditions and principles as injunctive relief against threatened

conduct that will cause loss or damage is granted by courts of equity . . .

15 U.S.C. 26.

2

of equity. United Stefa v. Borden Co., 347 U.S. 514, 518; Louisiana

Petroleum Retail Dealer*, Inc. v. Texaa Co.. 148 F. Supp. 334, 336

(W.D. La. 1956). Defendants argue that the appellants must also satisfy

3/the requirements of Section 4 of the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. 15,—

(applicable to treble damage plaintiffs) by alleging facts which show

an injury to appellants "business or property."

Appellants' complaint satisfies all these requirements. First,

it charges that defendants' conspiracy threatened plaintiffs with

personal "loss or damage" to their "business or property." It claims

that defendants' conspiracy injures the business of plaintiff real

estate brokers by denying them the "benefits of membership on the

Board, thereby restraining [their] . . . sale and rental of real prop

erty." (Complaint VII C). It claisw that the conspiracy— in preventing

willing homeowners from selling property in white neighborhoods to

Negroes— directly injures other Negro plaintiffs by artificially re

stricting where they can live (Complaint VII, E, F), and it injures

their property by forcing them "to pay more money than white persons

for equivalent housing" (Complaint VII 6). And, it claims that the

3/ Section 4 provides in relevant part: "Any person who shall be

injured in his business or property by reason of anything forbidden

in the antitrust laws may sue therefor . . . and shall recover three

fold the damages by him sustained . . . ." 15 U.S.C. 15.

3

conspiracy injura* cha proparty of whita plaintiffs by dapriving than

of "tha opportunity to sail or rant real proparty nora . . . profitably"

(Conplaint VII H). A conspiracy that forcas a buyar to pay higher prices

or a sailer to sell at lower prices injures tha "property" of tha buyar

and of the sellar. Chattanooga Foundry & Pipe Works v. City of Atlanta,

203 U.S. 390; Mandeville Island Farna, Inc, v. Anarlean Crystal Sugar Co..

334 U.S. 219; Georgia v. Evans, 316 U.S. 159; Thonsen v. Kaysar, 243 U.S.

66.

Second, the conplaint alleges facts which, if proved, would show

that defendants' conspiracy violates tha antitrust laws. Our argunent

to this affect is sat out in Brief for tha United States as Anicus Curiae,

pp. 17-22, to which we refer the Court. Third, if defendants prove the

facts alleged in their conplaint, they will have shown that they are

entitled to an injunction under ordinary principles of equity, because

they will have shown a substantial serious personal injury caused by

defendants' illegal conduct, because an injunction will not prove

inequitably burdensone to defendants, and, since the conspiracy is a

continuing one and since damages for at least some of the injury that

it causes plaintiffs may be hard to assess in monetary terms, because

plaintiffs' remedy at law is inadequate.

4

We do not mean to suggest by this discussion that we accept defen

dants' argument that plaintiffs in an action brought under Section 16

nust also sect Section 4's requirement of showing an injury to "business

or property"--particularly if the words "business or property" are inter

preted restrictively. While it may make sense in damage actions to limit

the type of harm for which money can be recovered to injuries to business

or property— injuries the dollar value of which can be more or less readily

ascertained--there is no reason to limit the type of harm that will jus

tify the issuance of an injunction to injuries that can be easily labeled

with a price tag. Moreover, the fact of a strong Congressional policy

favoring private antitrust actions, "one of the surest weapons for effec

tive enforcement of the antitrust laws," Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing

Co. v. New Jersey Wood Finishing Co., 381 U.S, 311, 318; Atlantic City

Electric Co., v. General Electric Co., 226 F. Supp. 59, 71 (S.D.N.Y.1964),

indicates that the courts should not engraft the restrictive requirements of

Section 4 on to Section 16. In fact, the Supreme Court has expressly warned

that the courts "should not add requirements to burden the private litigant

beyond what is specifically set forth by Congress." Radovich v. National

Football League, 352 U.S. 445, 454. And that Court has indicated that

"niggardly construction[s]" of statutes governing treble damage actions should

be avoided. Leh v. General Petroleum Corp., 382 U.S. 54, 59. See also Note,

5

64 Coluab. L. Rev., 570 (1964). But, in any event, wa submit that

even if this Court dacidas that plaintiffs oust aaat Section 4'a

requirements, thair complaint is adaquata, for it allagas facts suff

icient to satisfy tha raquiraaants of both Section 16 and Section 4.

Defendants argue, however, that Negroes wishing to buy or rent

houses in Akron's white neighborhoods and white homeowners wishing to

sell or rent those houses to Negroes lack standing to sue because they

are ultimate consumers and are not "businessman-competitors" of defen

dant real estate dealers (Defendants' Brief, pp. 33-35). But there

is no requirement that private plaintiffs be either businessmen or

competitors of antitrust defendants. Indeed, the antitrust laws,

which primarily protect "competition, not competitors," Brown Shoe

Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 344, are basically designed to

prohibit practices "which tend to raise prices or otherwise take from

buyers or consumers the advantages which accrue to them from free com

petition in the markets." Feddersen Motors, Inc, v. Ward, 180 F. 2d

519, 521 (10th Cir. 1950). [Emphasis added.] The SupresM Court and

lower courts have said over again that the Sherman Act protects "pur

chasers and consumers," Apex Hosiery Co. v. Leader, 310 U.S. 469, 498;

6

Mandeville Island Farms Co. v. American Crystal Sugar Co., supra at

236; Streiffer v. Seafarers Seachest Corp., 162 F. Supp. 602, 607

(E.D. La. 1958). And, they have said this for good reason, as many

hardcore antitrust violations, such as price fixing, will not hurt

the conspirators' competitors (indeed they may be enriched) but will

injure only consumers. Thus, it is not surprising that courts have

uniformly held that the antitrust laws give a private right of action

to purchasers of the goods and services involved in the restraint,

whether those purchasers are businessmen, e .£., Thomsen v. Kayser,

supra; Commonwealth Edison v. Allis-Chalmers Mfg. Co., 335 F. 2d 203

(7th Cir. 1964); Hanover Shoe, Inc, v. United Shoe Machinery Corp.,

185 F. Supp. 826 (M.D. Pa.), affirmed 281 F. 2d 481 (3rd Cir.),

cert, denied, 364 U.S. 901 (1960), or whether they are ultimate con

sumers. Chattanooga Foundry & Pipe Works v. City of Atlanta, supra,

(Holmes, J.: "[The City of Atlanta was] injured in its property, at

least, if not in its business of furnishing water, by being led to

pay more than the worth of the pipe" 203 U.S. at 396); Georgia v.

Evans, supra (Frankfurter, J.: "[Congress would not want to have

deprived] a State,as purchaser of commodities . . . , of the civil

remedy of treble damages which is available to other purchasers who

suffer through violation of the Act" 316 U.S. at 162); State of

Missouri v. Stupp Bros. Bridge & Iron Co., 248 F. Supp. 169 (W.D. Mo.

1965) ( state, as consumer of highways, sues highway equipment manufacturer);

7

Stitt of Illinois v» Brunswick Corp., 32 F.R.D. 453 (N.D. 111. 1963)

(stats, raprasanting school districts, suas makers of blaachar seats

sold to the school districts). Cf. Hanover Shoe, Inc. v. United Shoe

Machinery Corp., supra, at 831. See also Clark,"The Treble Damage

Bonanza: New Doctrines of Damages in Private Antitrust Suits," 52

_ 4 /

Mich. L. Rev., 363, 404 (1954).

In fact, because of the importance of private actions as an aid

to the enforcement of the antitrust laws, sea United States v. Borden

Co., supra, courts have held that purchasers who are middleman may

bring private actions against suppliers engaged in a price fixing con

spiracy even though price increases were passed on to the ultimate

consumer. E .£., Commonwealth Edison Co. v. Allis-Chalmers Mfg. Co.,

supra. It would be anomalous in the extresm to allow an antitrust

remedy to these middlesmn while denying it to ultimate consumers when

they bear the full brunt of an illegal conspiracy. Mora importantly,

to deny ultimata consumers an antitrust remedy would deprive the

government of any aid that private antitrust actions might give it in

preventing regional conspiracies at a retail level— conspiracies that

may not involve sufficient amounts of commerce to warrant investing the

government's enforcement resources. In sum, we can find no good reason

4/ Suits by ultimata consumers are infrequent because normally the

amount that could ba recovered would not justify the cost of suit.

8

for denylog plaintiff* in this casa standing to sue. Plaintiffs are

direct customers for the services, provided by defendant real estate

brokers. If, as plaintiffs claim, those services have been illegally

restricted, the restriction has injured them directly

Defendants also claim that the plaintiff real estate brokers lack

standing to sue because "they are not the persons who were intended to

be the victims of the alleged conspiracy" (Defendants' Brief, p. 40).

5/ The cases cited by defendants are not in point for they involve

suits (1) by a supplier to a company injured by an antitrust violation

(Snow Crest Beverages, Inc, v. Recip* Foods, Inc., 147 F. Supp. 907

(D. Mass. 1956)); (2) by employees of injured companies (Conference of

Studio Unions v. Loew's. Inc.. 193 F. 2d 51 (9th Cir. 1951)); Centonni

v. T. Smith & Son, 216 F. Supp. 330 (K.D. La. 1963); Rossi v. McCloskey

& Co., 149 F. Supp. 638 (E.D. Pa. 1957); and (3) by shareholders of

injured companies (Gomberg v. Midvale Co., 157 F. Supp. 132 (E.D. Pa.

1955)); Bookout v. Shine Chain Theaters, Inc., 253 F. 2d 292 (2d Cir.

1958). Even if the restrictive philosophy implicit in such opinions is

correct--* question not entirely free from doubt, see South Carolina

Council of Milk Producers, Inc, v. Newton, 360 F. 2d 414 (4th Cir. 1966);

Schulman v. Burlington Industries, Inc., 255 F. Supp. 847 (S.D.N.Y. 1966),

--they all involve plaintiffs who are not the direct victims of an anti

trust conspiracy but whose injuries follow incidentially from the injury

caused another. In each of these cases there exists a primary victim

free to bring a private suit. In the instant case, however, Negroes

seeking houses and white persons offering to sell them are the direct

customers of the service allegedly restricted, and Negro real estate

dealers are defendants' direct competitors. They are thus the direct

and primary victims of any illegal restriction. If they cannot sue to

obtain redress, no on* (except the government) can.

[Note: Insofar as the "employee" cases cited above involve employees

not working for an allegedly injured company, they may not state a

cans* of action under the entitrust laws because of the labor exemp

tion. See, Conference of Studio Union* v. Loew's Inc., supra.]

9

The complaint charges, however, that defendants "combined and conspired"

to exclude "Negro real estate brokers from the advantages and opportun

ities associated with membership in the defendant Board" (Complaint

VI C 8). And, it adds that as a result of the conspiracy, "Negro real

estate brokers have been denied benefits of membership on the Board

thereby restraining the sale and rental of real properties by such

brokers" (Conplaint, VIII C). It is difficult to see how that complaint

could have alleged more clearly that plaintiff real estate brokers were

intended direct victims of an illegal conspiracy. "It does not matter

that defendants under the allegations may be conspiring to produce the

restraints hurting plaintiffs only as part of an over-all scheme to

reach still bigger game. A conspiracy in antitrust law, as elsewhere,

may have a variety of objects and victims. Continental Ore Co. v. Union

Carbide & Carbon Corp.. 370 U.S. 690, 698-699." Schulman v. Burlington

Industries, Inc.. 255 F. Supp. 847, 851 (S.D.N.T. 1966). In fact, the

Supreme Court has specifically held that a victim of an illegal boycott

may bring a private antitrust action even though the ultimate purpose of

the boycott may not have been to injure him. Radovich v . National Foot

ball League, supra. Negro real estate brokers in this case qualify as

antitrust plaintiffs, for whatever the ultimate purpose of the alleged

illegal agraement to exclude them from the real estate board, such an

agreement by its very nature, had to be aimed at them and had to harm

them directly. See Schulman v. Burlington Industries. Inc., supra.

10

There is, thus, no nssd to give plaintiffs complaint that libaral

latituda in intarpratation to which it is antitlad, sae Noerr Motor

Freight, Inc, v. Kastarn Railroad Prasidants Confaranca, 113 F. Supp.

737, 742 (E.D. Penn. 1953); Package Closure Corp. v. Saalright Co.,

141 F. 2d 972, 979 (2d Cir. 1944); Maglar v. Admiral Corp., 248 F. 2d

319 (2d Cir. 1957), in order to sae that it alleges that defendants'

conspiracy in part directly aimed at and injured plaintiff real estate

brokers.

In sum, plaintiffs in this case represent direct customers for

the services of real estate brokers— services which defendants allegedly

illegally restrained. They also represent direct competitors. These

two groups of people, custoswrs and competitors, are the most important

of all those who are protected by the antitrust laws. They, if anyone,

were meant by Congress to have a private right of action to prevent

violations of the antitrust laws which injure them. And by giving such

persons private rights of action, Congress has provided an important

aid to the enforcement of the antitrust laws. Congress clearly did not

intend to leave antitrust enforcement of the type envisaged here entirely

in the hands of the Government. For these reasons, we submit, plaintiffs

do not lack standing to sue.

DONALD F. TURNER,

Assistant Attorney General,

STEPHEN G. BREYER,

Attorney.

MARCH 1967

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

1 hereby certify that 1 have this day caused the foregoing

Supplemental Brief Amicus Curiae to be served upon all parties

by causing a copy thereof to be mailed, postage prepaid and prop

erly addressed, to each of the following:

Jack Greenberg, Esquire

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Sidney D. L. Jackson, Jr., Esquire

Baker, Hostetler & Patterson

1965 Union Commerce Building

Cleveland, Ohio

Ivan L. Smith, Esquire

O'Neil & Smith

16 South Broadway

Akron, Ohio 44308

C. Blake McDowell, Jr., Esquire

Brouse, McDowell, May, Bierce & Wortman

500 First National Tower

Akron, Ohio 43308

V /K

Stephen G. Breyer

Attorney

MARCH 1 0t 1967