NAACP v. New York Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. New York Jurisdictional Statement, 1972. 98016440-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/40fa9b80-3355-4cc3-a99d-d435d3a28575/naacp-v-new-york-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

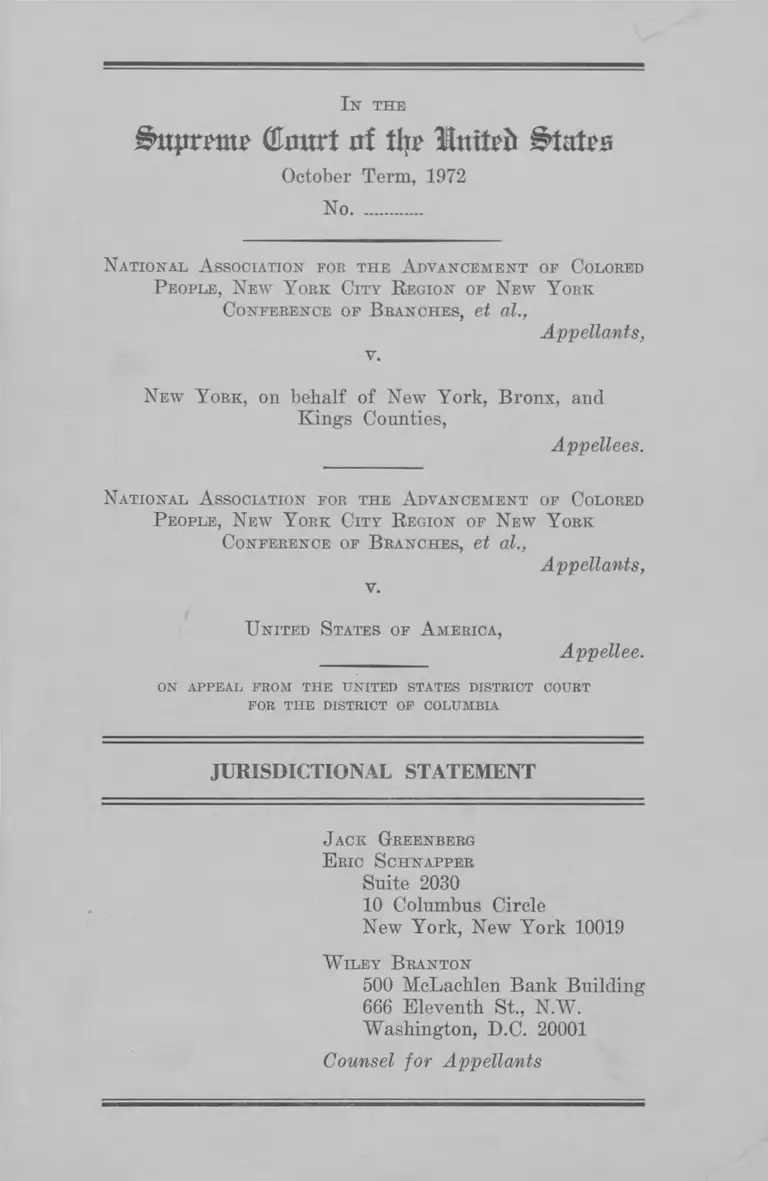

Bupumt (Emtrt of tfto Itttteii States

October Term, 1972

No..............

In th e

National A ssociation foe the A dvancement of Colored

People, New Y ork City R egion of New Y ork

Conference of B ranches, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

New Y ork, on behalf of New York, Bronx, and

Kings Counties,

Appellees.

National A ssociation for the A dvancement of Colored

People, New Y ork City R egion of N ew Y ork

Conference of B ranches, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

U nited States of A merica,

Appellee.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Jack Greenberg

E ric S chnapper

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

W iley B ranton

500 McLacklen Bank Building

666 Eleventh St., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

Counsel for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion B elow ........................................................................ 2

Jurisdiction ......................................................................... 2

Statutes Involved ............................................................... 3

The Question Presented .................................................. 7

Statement of the Case .............................................. 7

The Question Presented is Substantial............................ 11

1. The Cooper Amendment was expressly intended

to place three New York counties under sec

tions 4 and 5 of the Voting Rights A c t ............. 12

2. The United States improperly declined to op

pose exempting the three New York counties

from sections 4 and 5 ............................................ 16

3. The District Court clearly erred in granting

the exemption and denying appellant leave to

intervene ................................................................... 20

Conclusion ............................................................................. 28

A ppendix A —

Order of the District C ourt........................................ la

Judgment of the District Court ................................ 3a

Notice of A ppeal........................................................... 5a

A ppendix B—

Memorandum of the United States .......................... 7a

Affidavit of the Assistant Attorney General......... 8a

11

T able of A uthorities

Cases: page

Allen v. Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544 (1969) .......20, 21

Apache County v. United States, 256 F.Supp. 903

(D.Ct. D.C., 1966) ........................................................20,21

Cascade National Gas Corporation v. El Paso Natural

Gas Company, 386 U.S. 129 (1967) ...............21,22,26-27

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 330 F.Supp. 203 (S.D.

N.Y., 1971) ....................................................................... 25

Council of Supervisory Association of the Public

Schools of New York City v. Board of Education

of the City of New York, 23 N.Y.2d 458, 297 N.Y.S.2d

547, N.E.2d 204 (1969) .................................................. 25

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969) ....3,15,

18, 25, 27

In Be Skipwith, 180 N.Y.S.2d 852, 14 Misc. 2d 325

(1958) ............................................................................... 25

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966) ...........15,18, 27

National Association for the Advancement o f Colored

People v. New York City Board of Elections, 72

Civ. 1460 ......................................................................... 9, 20

Nuesse v. Camp, 385 F.2d 694 (D.C. Cir. 1967) ........... 22

Pellegrino v. Nesbit, 203 F.2d 263 (9th Cir., 1953) ....... 22

Pyle-National Co. v. Amos, 173 F.2d 425 (7th Cir.,

1949) ................................................................................. 22

Sam Fox Publishing Co. v. United States, 366 U.S.

683 (1961) ....................................................................... 20

S.E.C. v. Bloomberg, 299 F.2d 315 (1st Cir., 1962) .... 22

Stadin v. Union Elec. Co., 309 F.2d 912 (8th Cir., 1962) 22

United States v. Rosenberg, 195 F.2d 583 (2d Cir.,

1952) ................................................................................. 19

Statutes and Regulations:

28 U.S.C. §2284 ........................................................... 2

42 U.S.C. §1973b, Voting Rights Act of 1965,

§4 ................................................................... 2,3,7,8,12

42 U.S.C. §1973c, Voting Rights Act of 1965,

§5 ................................................................................... 5

Rule 24, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ............. 20

Other Authorities:

McCormick on Evidence ............................................ 19

3B Moore’s Federal Practice.................................... 20

Blascoer, Colored School Children in New York

(1915) ....................................................................... 24

Bulletin of the New York Public Library, “ Ethi

opia Unshackled: A brief history of the educa

tion of Negro Children in New York City”

(1965) ....................................................................... 24

Metropolitan Applied Research Center, Selection

From Stanines Study of 1969-70 (1972) ........... 23

Public Education Association, The Status of the

Public School Education of Negro and Puerto

Rican Children in New York City (1955) ......... 23

Report of the Mayor’ s Commission on Conditions

in Harlem ..............................................................23-24

United Bronx Parents, Distribution of Educational

Resources Among the Bronx Public Schools

(1968) ....................................................................... 23

36 Fed. Reg. 5809 ...................................................... 8

36 Fed. Reg. 18186-190 ............................................ 9

114 Cong. Rec........................................................ 13-16,18

116 Cong. Rec.............................................................. 12

Supreme (Emtrt of tlio Untttfi States

October Term, 1972

No..............

In th e

N ational A ssociation foe the A dvancement of Colored

People, New Y ork City R egion of New Y ork

Conference of B ranches, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

N ew Y ork, on behalf of New York, Bronx, and

Kings Counties,

Appellees.

National A ssociation for the A dvancement of Colored

People, New Y ork City R egion of New Y ork

Conference of B ranches, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

U nited S tates of A merica,

Appellee.

o n a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n it e d s t a t e s d is t r ic t c o u r t

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Appellants1 appeal from the judgment of the United

States District Court for the District of Columbia, entered

1 The appellants, applicants for intervention in the District

Court, are the New York City Region of New York Conference of

Branches of the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, Simon Levine, Antonia Vega, Samuel Wright,

Waldaba Stewart and Thomas Fortune.

2

on April 13, 1972, denying appellants’ motion to intervene,

and from the order of that court, entered on April 25,

1972, denying appellants’ motion to alter judgment. Appel

lants submit this Statement to show that the Supreme

Court of the United States has jurisdiction of the appeal

and that a substantial question is presented.

Opinion Below

The District Court for the District of Columbia issued

no opinion in connection with this case. The judgment of

the District Court, entered April 13, 1965, denying appel

lants’ motion to intervene, and the order of the District

Court, entered April 25, 1972, denying appellants’ motion

to alter judgment, are set out in Appendix A hereto.

Jurisdiction

This suit was brought by the State of New York, under

42 U.S.C. §1973b, to obtain for three counties of that state

an exemption from certain provisions of the Voting Rights

Act of 1970. The matter was heard before a three-judge

panel pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §1973b and 28 U.S.C. §2284.

Shortly after the United States declined to oppose the

granting of such an exemption, appellants moved to inter

vene as party defendants. The judgment of the District

Court denying that motion and granting the exemption

was entered on April 13, 1972, and the order of the District

Court denying appellants’ motion to alter judgment was

entered on April 25, 1972. The notice of appeal was tiled

in that court on May 11, 1972. The jurisdiction of the

Supreme Court to review this decision by direct appeal

is conferred by Title 42, United States Code, section

1973b(a). The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court to review

3

the judgment on direct appeal in this case is sustained in

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969).

Statutes Involved

Section 1973b, 42 United States Code, provides

§1973b. Suspension of the use of tests or devices in

determining eligibility to vote-Action by state or polit-

itical subdivision for declaratory judgment of no denial

or abridgement; three-judge district court; appeal to

Supreme Court; retention of jurisdiction by three-

judge court

(a) To assure that the right of citizens of the United

States to vote is not denied or abridged on account

of race or color, no citizen shall be denied the right

to vote in any Federal, State, or local election because

of his failure to comply with any test or device in any

State with respect to which the determinations have

been made under subsection (b) of this section or in

any political subdivision with respect to which such

determinations have been made as a separate unit,

unless the United States District Court for the District

of Columbia in an action for a declaratory judgment

brought by such State or subdivision against the

United States has determined that no such test or

device has been used during the ten years preceding

the filing of the action for the purpose or with the

effect of denying or abridging the right to vote on

account of race or color: Provided, That no such de

claratory judgment shall issue with respect to any

plaintiff for a period of ten years after the entry of

a final judgment of any court of the United States,

other than the denial of a declaratory judgment under

4

this section, whether entered prior to or after the

enactment of this subchapter, determining that denials

or abridgments of the right to vote on account of race

or color through the use of such tests or devices have

occurred anywhere in the territory of such plaintiff.

An action pursuant to this subsection shall be heard

and determined by a court of three judges in accor

dance with the provisions of section 2284 of Title 28

and any appeal shall lie to the Supreme Court. The

court shall retain jurisdiction of any action pursuant

to this subsection for five years after judgment and

shall reopen the action upon motion of the Attorney

General alleging that a test or device has been used

for the purpose or with the effect of denying or abridg

ing the right to vote on account of race or color.

If the Attorney General determines that he has no

reason to believe that any such test or device has

been used during the ten years preceding the filing of

the action for the purpose or with the effect of denying

or abridging the right to vote on account of race or

color, he shall consent to the entry of such judgment.

Required factual determinations necessary to al

low compliance with tests and devices; publication

in Federal Register

(b) The provisions of subsection (a) of this section

shall apply in any State or in any political subdivision

of a state which (1) the Attorney General determines

maintained on November 1, 1964, any test or device,

and with respect to which (2) the Director of the

Census determines that less than 50 per centum of the

persons of voting age residing therein were registered

on November 1, 1964, or that less than 50 per centum

of such persons voted in the presidential election of

November 1964. On and after August 6, 1970, in addi

5

tion to any State or political subdivision of a State

determined to be subject to subsection (a) of this

section pursuant to the previous sentence, the pro

visions of subsection (a) of this section shall apply

in any State or any political subdivision of a State

which (i) the Attorney General determines maintained

on November 1, 1968, any test or device, and with

respect to which (ii) the Director of the Census de

termines that less than 50 per centum of the persons

of voting age residing therein were registered on No

vember 1, 1968, or that less than 50 per centum of

such persons voted in the presidential election of No

vember 1968.

A determination or certification of the Attorney

General or of the Director of the Census under this

section or under section 1973d or 1973k of this title

shall not be reviewable in any court and shall be

effective upon publication in the Federal Register.

Definition of test or device

(c) The phrase ‘test or device’ shall mean any re

quirement that a person as a prerequisite for voting

or registration for voting (1) demonstrate the ability

to read, write, understand, or interpret any matter,

(2) demonstrate any education achievement or his

knowledge of any particular subject, (3) possess good

moral character, or (4) prove his qualifications by the

voucher or registered voters or members of any other

class.

Section 1973c, 42 United States Code, provides

§1973c. Alteration of voting qualifications and proce

dures; action by state or political subdivision for

declaratory judgment of no denial or abridgement of

6

voting rights; three-judge district court; appeal to

Supreme Court

Whenever a State or political subdivision with re

spect to which the prohibitions set forth in section

1973b(a) of this title based upon determinations made

under the first sentence of section 1973b(b) of this

title are in effect shall enact or seek to administer

any voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or

standard, practice, or procedure with respect to voting

different from that in force or effect on November 1,

1964, or whenever a State or political subdivision with

respect to which the prohibitions set forth in section

1973b(a) of this title based upon determinations made

under the second sentence of section 1973(b) of this

title are in effect shall enact or seek to administer any

voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or stan

dard, practice, or procedure with respect to voting

different from that in force or effect on November 1,

1968, such State or subdivision may institute an action

in the United States District Court for the District

of Columbia for a declaratory judgment that such

qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice, or pro

cedure does not have the purpose and will not have

the effect of denying or abridging the right to vote

on account of race or color, and unless and until the

court enters such judgment no person shall be denied

the right to vote for failure to comply with such

qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice, or pro

cedure : Provided, That such qualification, prerequisite,

standard, practice, or procedure may be enforced with

out such proceeding if the qualification, prerequisite,

standard, practice, or procedure has been submitted

by the chief legal officer or other appropriate official

of such State or subdivision to the Attorney General

and the Attorney General has not interposed an objec-

7

tion within sixty days after such submission, except

that neither the Attorney General’s failure to object

nor a declaratory judgment entered under this section

shall bar a subsequent action to enjoin enforcement

of such qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice,

or procedure. Any action under this section shall be

heard and determined by a court of three judges in

accordance with the provisions of section 2284 of

Title 28 and any appeal shall lie to the Supreme Court.

The Question Presented

Where the State of New York sues for an exemption

from sections 4 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,

as amended, and the United States expressly and without

justification declines to defend the action, should inter

vention be granted to a civil rights group and individuals

who have initiated other litigation to compel compliance

with sections 4 and 5 and who offer specific allegations

and substantial documentary evidence in opposition to

the granting of such an exemption.

Statement of the Case

Under the 1970 amendments to the Voting Rights Act

of 1965, three counties in the state of New York—Bronx,

Kings (Brooklyn) and New York (Manhattan)—are sub

ject to coverage by sections 4 and 5 of the Act. Those

sections are applicable because on November 1, 1968, New

York State employed a literacy test as a prerequisite to

registration and less than 50 percent of the persons of

voting age were registered on that date or voted in the

1968 presidential election in each of those three counties.

42 U.S.C. § 1973b(b). Section 5 provides that no changes

in the election laws or practices of such covered areas may

8

be enforced until the state or subdivision involved has

either submitted those changes to the Attorney General

without his objecting to them for a period of 60 days,

or has obtained a declaratory judgment from the United

States District Court for the District of Columbia that

the changes do not have the purpose and will not have

the effect of denying or abridging the right to vote on

account of race or color. 42 U.S.C. §1973c(a). Section 4

also provides that a state or subdivision subject to this

advance clearance procedure may obtain an exemption

therefrom by bringing an action for a declaratory judg

ment against the United States and obtaining from the

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

a determination that the literacy test employed by the

state or subdivision has not been used during the 10 years

preceding the filing of that action for the purpose or with

the effect of denying or abridging the right to vote on

account of race or color. 42 U.S.C. §1973b(a).

The 1970 amendments to the Voting Rights Act of 1965,

which for the first time subjected the three counties to

these special procedures, became law on June 22, 1970.

Although it was known at that time that the counties

would be covered, that coverage did not go into effect

until March 27, 1971, following the formal publication

of certain determinations by the Director of the Bureau

of the Census. See 36 Fed. Reg. 5809. On December 16,

1971, the state of New York brought this action in the

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

to secure an exemption for New York, Bronx and Kings

counties. The United States answered on March 10, 1972.

On March 17, 1972, New York moved for summary judg

ment.

During the pendency of this matter, but prior to any

action therein by the District Court, the State of New

9

York enacted legislation altering the boundaries of the

congressional, Assembly, and State Senate districts in the

three counties. The statute altering the Assembly and

Senate districts was enacted on January 14, 1972, and on

January 24, 1972 these changes were submitted to the

Attorney General by the state of New York. On March

14, 1972, the Attorney General rejected the submission

on the ground that it lacked information required by the

applicable regulations. 36 Fed. Reg. 18186-190. The changes

in the congressional districts, enacted on March 28, 1972,

were never submitted to the Attorney General. Immedi

ately upon the passages of these two redistricting laws

and despite the absence of compliance with sections 4

and 5, officials in all three counties took steps to implement

the changes, including redistribution of voter registration

cards among the new districts and printing and distribut

ing nomination petitions.

On March 21, 1972, counsel for appellants informed the

Department of Justice by telephone that appellants in

tended to bring an action to enjoin enforcement of the

new district lines until section 5 had been complied with,

and indicated that appellants would urge the Attorney

General to object to the new district lines when they were

submitted to him on the ground, inter alia, that the lines

had been drawn in such a way as to minimize the voting

strength of blacks, Puerto Ricans, and other minorities.

Such an action was filed by appellants 17 days thereafter

in the Southern District of New York, National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People v. New York City

Board of Elections, 72 Civ. 1460. Counsel for appellants

also advised the Department attorneys that the New York

Advisory Committee to the United States Civil Rights Com

mission intended to hold hearings in April, 1972 regarding

the new district lines in the three counties to assist the

10

Commission in deciding whether to urge the Attorney Gen

eral to object to those changes in New York law. During the

same discussion with the Department of Justice, counsel

for appellants learned for the first time of the pendency

of the instant action and of New York’s motion for sum

mary judgment. On three separate occasions, March 21,

March 29, and April 3, 1972, counsel for appellant was

expressly assured by Justice Department attorneys that

the United States would oppose any exemption for the

three counties and was preparing papers in opposition

to the motion for summary judgment. At no time did any

representative of the Department, though fully aware of

appellants interest in this action, seek from appellants or

their counsel, or indicate any interest in, information

regarding the central issue in the instant case—whether

New York’s literacy tests had been used in the three coun

ties over the previous decade with the purpose or effect of

denying or abridging the right to vote on account of race

or color.

On April 3, 1972, the Assistant Attorney General in

charge of the Civil Rights Division executed a 4 page affi

davit on behalf of the Attorney General stating that the

United States had no reason to believe that literacy tests

had been used in New York, Kings or Bronx counties in

the previous 10 years with the purpose or effect of denying

or abridging the right to vote on account of race or color.

The affidavit was filed with the District Court for the Dis

trict of Columbia the next day, together with a one sentence

memorandum consenting to the entry of the declaratory

judgment sought by New York. (The Affidavit and Memo

randum are set out in Appendix B.) On the afternoon of

April 5, 1972, counsel for appellants was notified by tele

phone of the Justice Department’s reversal of its earlier

position. Appellants moved to intervene as party defen

dants in the instant proceeding on April 7, 1972.

11

Appellants’ motion to intervene was opposed by New

York; the United States has filed no further papers in the

case. On April 13, 1972, the District Court denied without

opinion appellant’s motion to intervene and entered judg

ment in favor of plaintiff. On April 24, 1972, appellants

moved the District Court to alter its judgment. That mo

tion was denied without opinion on April 25, 1972.2 This

appeal followed.3

The Question Presented is Substantial

The instant action arises from an attempt by the state of

New York to nullify one of the most important of the

1970 amendments to the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The

amendment in question proposed on the Senate Floor by

Senator Cooper, altered the formula in sections 4 and 5

of the Act with the express purpose of extending their

coverage to more than 2 million blacks and Puerto Ricans

in New York, Bronx and Kings counties. The United

States systematically declined to investigate or present to

the court below any of the factual or legal theories which

had prompted Congress to extend coverage to these three

counties and which had earlier been advanced by the United

States before congressional committees and this Court.

The Voting Rights Act does not authorize the Attorney

General to grant exemptions to sections 4 and 5, but re

quired the court below to make its own independent deter

mination that the three counties had not used literacy tests

with the proscribed purpose or effect. In the face of the

2 The order denying this motion was signed by only 2 members

of the three judge panel. Judge Greene, for unexplained reasons,

did not participate.

3 By agreement of counsel no further action has been taken by

either party in the New York action pending a final decision in

the instant case.

12

refusal of the United States to offer to the court relevant

evidence or arguments in this regard, the district court

should have permitted appellants to intervene and assist

it by presenting such material.

1. The Cooper Amendment was expressly intended to place

three New York counties under sections 4 and 5 of the

Voting Rights Act.

Under the 1965 Voting Rights Act as originally enacted

the requirements of sections 4 and 5 regarding federal

clearance of new voting laws and practices were applied to

any state or subdivision which met two criteria: (1) on

November 1, 1964, it had in effect a test or device as defined

in section 4(c), 42 U.S.C. §1973b(c), such as a literacy test,

and (2) less than 50 percent of the voting age population

was registered on November 1,1964, or less than 50 percent

of such persons voted in the 1964 presidential election.

Most of the covered areas were located in the south; Ala

bama, Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia, South Carolina,

Virginia, and 40 counties of North Carolina were subjected

to the clearance procedures. In the north 6 scattered

counties and the state of Alaska were also covered. Between

the enactment of the 1965 Act and the 1970 amendments

only one county in the South was able to obtain an exemp

tion; in the north, however, Alaska and at least 4 of the

affected counties obtained, with the concurrence of the

Attorney General, declaratory judgments exempting them

from sections 4 and 5. See 116 Cong. Rec. 5526, 6521, 6621,

6654 (1970).

Sections 4 and 5 of the 1965 Act were so framed as to

automatically expire in 1970. Extension of these provisions

was proposed for a period of 5 years until 1975, but both the

Administration and many members of Congress opposed

any such extension. The principal criticism voiced by

13

these opponents and recurring throughout the history of

the 1970 amendments was that sections 4 and 5 applied

almost exclusively to the South, and constituted discrimina

tory regional legislation. Renewal of the sections was

initially rejected by the House on this ground.4 AVhen the

measure was considered by the Senate, the same argument

was advanced.5 Critics of sections 4 and 5 reiterated that

discrimination was a national problem and could be found

even in the city of New York.6 In particular it was re

peatedly pointed out that New York, Kings and Bronx

Counties, which did not fall under the 1965 Act, would have

been covered by sections 4 and 5 of the Act if the formula

contained therein had referred to registration and voting

turnout in November 1968 instead of November 1964.7

In response to these arguments Senator Cook proposed

that sections 4 and 5 be altered so as to cover states and

subdivisions which had the specified tests or devices and

low registration or presidential vote in either 1964 or 1968.

Senator Cooper explained his amendment in the following

terms:

The pending amendment would bring under coverage

of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and under the trig

gering device described in section 4(b), those States or

political subdivisions which the Attorney General may

determine as of November 1, 1968, employed a test or

4113 Cong. Rec. 38485-38537 (1969).

5 See generally 114 Cong. Ree. 5516— 6661 (1970).

6114 Cong. Rec. 5534 (Remarks of Senator Hansen), 5670 (Re

marks of Senator Byrd), 5687-8 (Remarks of Senator Long), 6158

(Remarks of Senator Gurney), 6161-63 (Remarks of Senator El-

lender) (1970), 6621-22 (Remarks of Senator Long).

7114 Cong. Rec. 5546 (Remarks of Senator Ervin), 6151-52

(Remarks of Senator Ellender), 6623-25 (Remarks of Senator

Allen) (1970).

14

device and where less than 50 percent of persons of

voting age were registered or less than 50 percent of

such persons voted in the presidential election of 1968.

* * *

One of its purposes is to establish the principle that

the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and, in particular, its

formula, section 4(b), which is called the trigger, is ap

plicable to all States and political subdivisions and is

not restricted to the Southern States.

* # #

The amendment also establishes the principle which

has been approved in our debate—that legislation to

secure the voting rights must apply to all the people of

this country, and to all the States. It is not restricted

to a fixed date in the past, whether 1964 or 1968. It is

a continuing effort to secure and assure voting rights

to all the people of our country.

# # *

The chief State involved is the State of . . . New

York. Three counties of New York were involved,

Bronx, Kings, and New York. In the 1964 election more

than 50 percent of the voters were registered and more

than 50 percent voted. However, for some reason in the

1968 election 50 percent were not registered or voting.

114 Cong. Rec. 6654, 6659 (1970).

Although opposed by the Senators from New York, the

Cooper amendment was passed with the support of Senators

from all regions of the country. 114 Cong. Rec. 6661. When

the Senate bill was brought up for consideration, both the

Chairman of the Judiciary Committee and the Majority

Leader noted that the new version applied to New York,

Kings and Bronx Counties, the latter noting that this

15

change demonstrated that the Act was not “aimed at any

one section.” 8 The House, which had earlier rejected re

newal of sections 4 and 5, acquiesced in their reenactment

as thus modified.9

The Senate debates leading to the passage of the Cooper

amendment reveal a variety of concerns as to the manner in

which New York’s literacy test had had a discriminatory

purpose or effect in the three counties involved. (1) Senator

Cooper, referring to this Court’s decision in Katzenbach v.

Morgan, 384 U.S. 641, 654 n.14 (1966), urged that New

York’s 1922 literacy requirement was enacted, with the

purpose of discriminating on the basis of race.10 (2) Sena

tor Griffin argued that if New York denied the vote to il

literate black applicants who had received an inferior educa

tion in a segregated southern school system, the literacy

test would have the effect of discrimination on the basis of

race in a manner which this Court had earlier held to con

stitute the type of discrimination which precludes an ex

emption from sections 4 and 5.11 (3) Senator Hruska, quot

ing testimony by the Attorney General, suggested it would

also discriminate on the basis of race to deny the franchise

to illiterates who had received an inferior education in the

north, without regard to whether a de jure dual school sys

tem might be involved.12 (4) Again quoting the Attorney

General, Senator Hruska suggested that the mere use of

8 114 Cong. Rec. 20161 (Remarks of Rep. Celler), 20165 (Re

marks of Rep. Albert) (1970).

0114 Cong. Ree. 20199 (1970).

10114 Cong. Ree. 6660 (1970); see also 114 Cong. Rec. 6659

(Remarks of Senator Murphy).

11114 Cong. Ree. 6661; see also 114 Cong. Rec. 5533 (Remarks

of Senator Hruska), 6158-9 (Remarks of Senators Dole and Mit

chell) (1970); Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285

(1969).

12114 Cong. Rec. 5533 (1970).

16

literacy tests had a psychological effect which tended to

deter blacks who might seek to register and thus have a

racially discriminatory effect.13 (5) Several Senators sug

gested that literacy tests were discriminatory in effect

merely because the rate of illiteracy was higher among

blacks or other minorities than among whites.14 15

The Cooper amendment expanded substantially the num

ber of persons protected by sections 4 and 5. The three New

York counties concerned have a total black population of

1.4 million and another 800,000 Puerto Ricans.16 The com

bined minority population of these counties is almost double

that of the largest southern state covered by the A ct; Kings

County alone has nearly as many black residents as do the

states of Virginia and South Carolina. All the exemptions

granted by the federal courts prior to the instant case af

fected a total of no more than 100,000 minority group mem

bers. By granting an exemption to New York, Kings and

Bronx counties, the court below not only nullified the

Cooper amendment, but withdrew the protection of sections

4 and 5 from an area of unprecedented size.

2. The United States improperly declined to oppose exempt

ing the three New York counties from sections 4 and 5.

The affidavit submitted by the United States below, and

set out in Appendix B, acquiescing to the exemption for

the three counties reveals an incomprehensible failure by

the Justice Department to pursue the legal and factual

concerns which led to the passage of the Cooper amend

ment. The investigation conducted by the Department “ con

13114 Cong. Rec. 5533; see also 114 Cong. Rec. 6152 (Remarks

of Senator Eastland) (1970).

14114 Cong. Rec. 5532-3 (Remarks of Senator Hruska), 6152

(Remarks of Senator Eastland), 6156 (Remarks of Senator Gur

ney) (1970).

15 Unpublished figures supplied by the Bureau of the Census.

17

sisted of examination of registration records in selected

precincts in each covered county, interviews of certain elec

tion and registration officials and interviews of persons

familiar with registration activity in black and Puerto

Rican neighborhoods in those counties.” (Appendix, p.

8a) So far as appears from the government’s papers, its

investigators may never have interviewed any person not

interested in obtaining the exemption or even any black or

Puerto Rican. None of the appellants or their counsel, all

of them known to be vitally interested in this case, were

ever interviewed or even informed by the Justice Depart

ment that any investigation was underway. An examina

tion of the registration records was well calculated to re

veal nothing other than clumsily concealed discrimination

in the application of the literacy tests, and the legislative

history of the Cooper amendment reveals that that was one

of the few types of discrimination Congress did not con

sider. The results of this investigation were predictably

barren. Beside detailing the extent to which election offi

cials had failed at first to comply with the 1965 federal ban

on English language literacy tests to deny the vote to

Puerto Ricans with at least a sixth grade education, and

with the 1970 federal prohibition against all literacy tests,

the affidavit lamely recites that the interviews with election

officials and other unnamed knowledgeable persons “ re

vealed no allegation by black citizens that the previously

enforced literacy test was used to deny or abridge their

right to register and vote by reason of race or color.”

(Appendix, p. 9a)

The most striking aspect of the government’s affidavit

and one page affidavit are the omissions. No inquiry was

made as to whether New York’s literacy tests were dis

criminatory because blacks or Puerto Ricans in the three

counties had a higher rate of illiteracy than whites due to

unequal educational opportunities in the three counties, an

18

approach which the United States had pressed with vigor

three years before in Gaston County v. United States, 395

U.S. 285 (1969), and which the Attorney General had

urged before Congress.16 No inquiry was made as to

whether the tests discriminated against blacks who had

received an inferior segregated education in the south and

then moved to New York, a species of discrimination which

the Attorney General had condemned two years earlier in

congressional testimony noted on the floor of the Senate.17

No inquiry was made as to whether New York’s literacy

test had been enacted with the express purpose of disen

franchising minority groups, a matter which the United

States itself had earlier brought to the attention of this

Court in Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641, 654 (1966).

No inquiry was made into the psychological barrier to

black registration inherent in literacy tests which the At

torney General had noted two years earlier.18 And no

inquiry of any kind was made of appellants in the instant

case, all of whom the United States knew to be vitally

interested in the pending request for an exemption from

sections 4 and 5. This lack of inquiry is particularly sur

prising in view of the concern openly expressed in the

Senate during the 1970 debates that the Attorney General

had or would abuse his discretion by opposing exemptions

for southern states while readily acquiescing to any simi

lar requests from the north.19

Under section 4 of the Voting Eights Act the Attorney

General is not vested with the authority to grant exemp

tions from the federal clearance procedures. Unlike sec- 16 17 18 19

16 See 114 Cong. Rec. 5533 (1970).

17 See 114 Cong. Rec. 6158-59 (Remarks of Senator Dole) (1970).

18 See 114 Cong. Rec. 5533 (1970).

19114 Cong. Rec. 6166 (Remarks of Rep. Poff), 6521 (Remarks

of Senator Ervin), 6621 (Remarks of Senator Ervin).

19

tion 5, which confers upon the Attorney General discretion

to object or assent to changes in voting laws, section 4

provides that exemptions may be given only by a three

judge federal court, and then only after that court has

made a determination of fact that the jurisdiction involved

has not used any tests or devices during the previous 10

years for the purpose or with the effect of denying or

abridging the right to vote on account of race or color.

This difference between sections 4 and 5 dictates that the

Attorney General’s consent cannot control the decision or

alter the responsibility of the district court. Even in the

face of the government’s acquiescence in the requested

exemption in the instant case, the court below had an

unequivocal duty to make an informed and independent

judgment concerning the legal and factual issues raised

by that request. Particularly in a case such as this, involv

ing as it does matters of great public import, the district

court does not function as a mere umpire or moderator

bound to accept any arrangement proposed by the named

parties, but sits to see that justice is done not only to

those parties but to all who may be affected by its decision.

Compare United States v. Rosenberg, 195 F.2d 583 (2d

Cir., 1952), certiorari denied, 344 U.S. 838. Under certain

circumstances it may be proper, for example, for the dis

trict court to call and examine its own witnesses when the

parties decline to do so. McCormick on Evidence, 12-14.

Certainly in a case such as this, where New York seeks to

withdraw the protection of sections 4 and 5 from more

than 2 million blacks and Puerto Ricans, and the United

States declines either to present the court with relevant

evidence or to advance any related legal considerations,

the responsibilities imposed upon the district court by

section 4 dictate that it accept the assistance of responsi

ble intervenors.

20

3. The District Court clearly erred in granting the exemption

and denying appellants leave to intervene.

Rule 24(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure pro

vides that intervention shall be permitted as of right “when

the applicant claims an interest relating to the property

or transaction which is the subject of the action and he is

so situated that the disposition of the action may as a

practical matter impair or impede his ability to protect

that interest, unless the applicant’s interest is adequately

represented by the parties.” This language is the result

of the 1966 amendments intended to liberalize intervention

and to make it available to any party whose interests might

be substantially affected by the disposition of the ac

tion. See Committee Note, 3B Moore’s Federal Practice

If 24.01 [10]. The advisory committee expressly departed

from the pre-1966 requirement that the applicant for in

tervention show that he would be legally bound by the

judgment as res judicata. Compare Sam Fox Publishing

Co. v. United States, 366 U.S. 683 (1961). Apache County

v. United States, 256 F. Supp. 903 (D.Ct. D.C., 1966). A

liberal attitude toward private action to vindicate the pub

lic interest is generally desirable in litigation arising out

of civil rights legislation. Compare Allen v. Board of Elec

tions, 393 U.S. 544 (1969).

The requirements of Rule 24(a) are clearly met in the

instant case. Appellants have brought suit in the United

States District Court for the Southern District of New

York to compel the three counties to comply with sections

4 and 5 and submit their redistricting laws for federal

approval. National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People v. Neiv Yorh City Board of Elections, 72

Civ. 1460. Unless the three counties receive an exemption

from sections 4 and 5, appellants will almost certainly

succeed in obtaining the injunctive relief sought in the

21

New York action. If, however, the counties obtain such an

exemption in the instant action, appellants will of course

be unable to compel the counties to submit their redistrict

ing plans to the Attorney General. Appellants also seek

to intervene on behalf of themselves, the members of appel

lant New York N.A.A.C.P., and all other minorities who

will be denied the protections of sections 4 and 5 if the

three counties are exempted from coverage. This Court

has already held, at the urging of the United States, that

“ [i]t is consistent with the broad purpose of the [Voting

Eights] Act to allow the individual citizen standing to

insure that his city or county government complies with

the §5 approval requirements.” Allen v. Board of Elec

tions, 393 U.S. 544, 557 (1969). That policy and appellants’

interest are the same whether appellants seek to assure

such compliance by suing the New York or intervening in

the District of Columbia, and apply a fortiori in an inter

vention such as this one where appellants seek to compel

compliance with sections 4 and 5 with regard to all changes

in voting laws or practices which may occur in the future.

Both because they will be bound in the New York litigation

by an exemption in the instant case, and because of the

impact on them and of those whom they represent of a

withdrawal of the protections of sections 4 and 5, appel

lants have a substantial interest in the disposition of the

instant litigation and are entitled as of right to intervene.

Compare Cascade National Gas Corporation v. El Paso

Natural Gas Company, 386 U.S. 129 (1967). The instant

application for intervention also falls within the authority

of the court to grant permissive intervention deemed help

ful to the court. Apache County v. United States, 256

F.Supp. 903,908 (D.Ct. D.C. 1966).

That the United States does not adequately represent

appellants’ interests can hardly be disputed. The burden

22

of showing adequacy of representation is on the party

opposing intervention. Nuesse v. Camp, 385 F.2d 694 (D.C.

Cir. 1967). The claim of inadequacy in the instant case

is not based on a mere tactical disagreement as to how

this litigation should be conducted, but upon the express

refusal of the United States to present to the district

court any factual evidence or legal argument in opposition

to the requested exemption. Compare Stadin v. Union

Elec. Co., 309 F.2d 912, 919 (8tli Cir., 1962), certiorari

denied, 373 U.S. 915; Pellegrino v. Nesbit, 203 F.2d 463

(9th Cir., 1953). The complete failure of representation

revealed in the instant case far exceeds the showing of

inadequacy found sufficient by this Court in Cascade Natur-

ral Gas Corporation v. El Paso Natural Gas Company,

386 U.S. 129 (1967).

Nor can the timeliness of appellants’ application for

intervention be doubted. The motion for intervention was

filed 2 days after appellants were informed that the United

States had decided not to oppose the requested exemption.

Prior to that time the government had consistently indi

cated that it would oppose the exemption; until the United

States suddenly reversed its earlier position there was no

reason to question the adequacy of its representation and

any motion to intervene would have been premature. Com

pare S.E.C. v. Bloomberg, 299 F.2d 315, 320 (1st Cir.,

1962). The motion was made prior to the commencement

of any trial, the argument of any motion or the issuance

of any orders by the district court. Compare 3B Moore’s

Federal Practice, H 24.13 [1]. The circumstances in the

instant case are similar to those in Pyle-National Co. v.

Amos, 173 F.2d 425 (7th Cir., 1949). In Pyle-National,

an action by a corporation against its former officers for

an accounting for certain sums, a stockholder sought to

intervene as a party defendant six months after the litiga

23

tion had commenced and a matter of weeks before the

scheduled commencement of the trial. The stockholder only

moved to intervene when he learned that the corporation

was about to consent to judgment for much less than the

full amount allegedly misappropriated by the defendants.

The Court of Appeals held the application for intervention

timely. 172 F.2d at 428.

Appellants’ motion for intervention and supporting

papers sought to present the theories of discrimination in

the use of New York’s literacy test which had been urged

by the Attorney General and accepted by Congress in en

acting the Cooper amendment. Appellants asked an oppor

tunity to show that the literacy test had had the effect or

purpose of discriminating on the basis of race because,

inter alia, the rate of illiteracy was higher among non

whites than among whites, the counties had for many

years provided blacks and Puerto Ricans with an educa

tion inferior to that provided whites, that many of the

black adults had emigrated to New York from southern

states where they had attended inferior segregated schools,

and the literacy tests were administered in such a way and

with the effect of deterring minority group members from

attempting to take them. To demonstrate the substantiality

of these claims of discrimination, appellants furnished the

district court with copies of six official and semi-official

reports from 1915 to 1970 documenting the extent of dis

crimination against minority children in New York City

schools,20 developed extensive statistics from available

20 Metropolitan Applied Research Center, Selection From

Stanines Study of 1969-70 (1972) ; United Bronx Parents, Dis

tribution of Educational Resources Among the Bronx Public

Schools (1968); Public Education Association, The Status of the

Public School Education of Negro and Puerto Rican Children in

New York City (1955) (A report prepared for the New York City

Board of Education) ; Report of the Mayor’s Commission on Con

ditions in Harlem, chapter 5, “ The Problem of Education and

24

census and other data showing the resulting differences

in illiteracy rates,21 and referred the court to judicial deci

sions condemning racial discrimination in both the New

Recreation” (1935); Blaseoer, Colored School Children in New

York (1915); Bulletin of the New York Public Library, “ Ethiopia

Unshackled: A brief history of the education of Negro Children

in New York City” (1965). The Public Education Association Re

port, for example, compared facilities in schools with less than 10%

blacks and Puerto Ricans (denoted Y schools) with those in schools

less than 10 or 15% white students (denoted X schools). The Re

port found that the average Group X elementary school was 43

years old, while the average group Y elementary school was 31

years old. The average Group X junior high school was 35 years

old; the average Group Y junior high school was 15 years old.

Group X schools were generally equipped with fewer special rooms

than Group Y schools, and principals in Group X schools were

generally less satisfied with their facilities and equipment than

those in Group Y schools. An average of 17.2 years had gone by

since the last renovation of the Group X elementary schools and

4.3 years for the group X junior high schools; renovation had

occurred on the average only 9.8 years before in the Group Y

elementary schools and 0.7 years earlier in the Group Y junior

high schools, even though the Group Y schools were newer to begin

with. Twice as many Group X elementary teachers were on proba

tion as in Group Y, 50% more Group Y elementary teachers had

tenure than Group X , and more than twice as many Group X

elementary school teachers were under-trained permanent substi

tutes. The Board of Education was spending an average of $8.30

per student for maintenance in Group Y elementary schools, but

only $5.30 per student in Group X elementary schools. Expen

ditures for operation of school plant were $27.50 per child at

Group Y elementary schools and $19.20 per child in Group X

elementary schools. The expenditure per student for instruction

was $195 in the Group Y elementary schools and $185 in the Group

X elementary schools. The average class size in ordinary Group X

elementary schools was 35.1, compared to 31.1 in the comparable

Group Y schools. The Report also concluded that it had not been

the policy of the Board of Education in drawing school district

lines to seek to ameliorate the racial isolation caused by housing

patterns.

21 Those statistics revealed the following. Between 1910 and

1960, when most persons of voting age before 1972 received their

education, the proportion of non-white children between 7 and 13

not enrolled in school exceeded the white rate by an average of

30%, and was higher in 1960 than ever before. In 1950 the propor-

25

York City school systems and in school systems in the

south from which black residents of the 3 counties had

emigrated.* 22

Notwithstanding the plainly adequate allegations and

substantial evidence of discriminatory use and purpose of

New York’s literacy test, the district court ruled for the

plaintiffs without ever reaching the merits of the issues

tion of children ages 7 to 13 more than one grade behind in school

was approximately 75% higher among non-white children than

among white children, and the amount by which the non-white

rate exceeded the white rate actually rose the longer the children

had been enrolled in school. A more recent study showed that

white students in white elementary schools were a year and a half

to two years ahead of black and Puerto Rican students in non

white New York schools, and the gap in reading ability widened,

the longer the students were enrolled in school. The tendency of

non-white children in non-white schools to fall further and further

behind white children in white schools in New York City was noted

in Council of Supervisory Association of the Public Schools of

New York City v. Board of Education of the City of New York,

23 N.Y.2d 458, 463, 297 N.Y.S.2d 547, 551, 245 N.E.2d 204, 207

(1969) modified on appeal, 24 N.Y.2d 1029, 302 N.Y.S.2d 850,

250 N.E.2d 251. In 1960, while literacy tests were employed in

all three counties, the rate of illiteracy among non-whites was

230% higher than among native whites in New York County,

270% higher than among native whites in Kings County, and

310% higher than among native whites in Bronx County. In

Gaston County v. United States the rate of illiteracy among blacks

was only 70% higher than among whites. 288 F.Supp. 678, 687

(D.C. Cir., 1968).

22 Chance v. Board of Examiners, 330 F.Supp. 203 (S.D.N.Y.,

1971) (Examinations used by 80 year old Board of Examiners of

the City of New York discriminated against non-white applicants

for employment in the public school system); In Re Skipwith, 180

N.Y.S.2d 852, 14 Misc. 2d 325 (1958) ; Gaston County v. United

States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969). The court in Skipwith found inter

alia, (a) that the New York public schools were segregated on

the basis of race, (b) that this segregation, whether or not purpose

ful, had a harmful effect on the education of the non-white children,

(c) that the use of less qualified substitute teachers was almost

twice as frequent in non-white schools as in white schools in the

three counties, (d) that there was a higher proportion of inex

perienced teachers in the non-white schools.

26

raised. The motion of appellants which was accompanied

by the extensive documentation and statistics noted above

was denied by the court the day after it was filed. In as

much as the court below issued no opinions in connec

tion with this case, it is impossible to determine why

appellants’ motion to intervene was denied. The final

judgment appealed from merely recites that plaintiff’s

motion for summary judgment is granted. There was no

express determination by the district court regarding the

discriminatory purpose or effect of New York’s literacy

test; it is unclear whether the members of the court ever

made such a determination, or instead felt authorized or

compelled by the government’s position to simply grant

the motion for summary judgment. Although section 5

requires the district court to retain jurisdiction in this

action for a period of five years after judgment, the United

States did not ask the court to retain jurisdiction and that

court did not do so. The proceedings in the district court

were, in sum, entirely devoid of the caution and scrutiny

which Congress can be assumed to have contemplated

would be exercised before the protections of sections 4

and 5 were withdrawn from over 2 million blacks and

Puerto Ricans.23

The mere fact that appellants seek to intervene on the

side of the United States does not preclude granting that

request. This Court has already held that private parties

may seek to step forward and seek to vindicate the public

interest when dissatisfied with the government’s handling

of a case in which they have a substantial interest. Cascade

23 Since the district court never actually entered a declaratory

judgment determining that no test or device as defined in the Act

had been used during the previous 10 years for the purpose or

with the effect of denying or abridging the right to vote on account

of race or color, the purported exemption does not meet even

the literal requirements of the statute.

27

Natural Gas Corporation v. FA Paso Natural Gas Company,

386 U.S. 129 (1967). The instant case does not involve

any settlement negotiated by the United States to which

a private party seeks to object and the United States did

not oppose the motion for intervention. Appellants do

not seek to substitute their judgment for that of the United

States on some matter of public policy. Compare Cascade

Natural Gas, 386 U.S. at 141-161 (dissent of Justice Stew

art). Nor do appellants seek to introduce before the district

court factual material presented earlier and without suc

cess to the United States. Compare Apache County v.

United States, 256 F.Supp. 903 (D.Ct. D.C., 1966). The

legal theories which appellants ask to present as to what

constitutes discriminatory purpose or effect are the very

theories urged by the United States before this Court in

Katzenbach v. Morgan and Gaston County v. United States,

advanced by the Attorney General at congressional hear

ings on the instant statute, and accepted by the Congress

which voted the Cooper amendment into law. The evidence

which appellants seek to introduce is the evidence plainly

relevant under those accepted interpretations of section 4

which the United States neither sought on its own nor

asked or permitted appellants to bring to its attention.

Under these circumstances the decision of the district court

denying appellants’ motion to intervene was not only erro

neous under Rule 24 but inconsistent with the policies of

the Voting Rights Act.

28

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons probable jurisdiction should

be noted, and the judgment below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

E ric S chnapper

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

W iley B ranton

500 McLachlen Bank Building

666 Eleventh St., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

Counsel for Appellants

APPENDICES

la

APPENDIX A

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F oe the D istrict of Columbia

Civil Action No. 2419-71

Order o f the District Court

N ew Y ork S tate, on behalf of New York, Bronx

and Kings Counties,

Plaintiff,

vs.

U nited States of A merica,

Defendant,

N .A .A.C .P ., N ew Y ork City Region of New Y ork State

Conference of B ranches, et al.,

Applicants for Intervention.

This matter came before the Court on Motion by plain

tiff, New York State, for Summary Judgment, a response

by defendant, United States of America, consenting to the

entry of such judgment, and a Motion to Intervene as party

defendants by the N.A.A.C.P., New York City Region of

New York State Conference of Branches, et al.

Upon consideration of these Motions, the memoranda of

law submitted in support thereof, and opposition thereto,

it is by the Court, this 12th day of April 1972,

Ordered that said Motion to Intervene as party defen

dants by N.A.A.C.P., New York City Region of New York

2a

Order of the District Court

State Conference of Branches, et al. should be and the

same hereby is denied, and it is

F urther Ordered that the Motion for Summary Judg

ment by plaintiff, New York State, should be and the same

hereby is granted.

/ s / E dward A llen T amm

/ s / W illiam B. Jones

/ s / June Green

F iled

A pril 13, 1972

James F. Davey, Clerk

3a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

P oe the D istrict op Columbia

Civil Action No. 2419-71

Judgment o f the District Court

New Y ork State, on behalf of New York, Bronx

and Kings Counties,

Plaintiff,

vs.

U nited States op A merica,

Defendant,

N.A.A.C.P., New Y ork City Region of New Y ork State

Conference of B ranches, et al.,

Applicants for Intervention.

Before T am m , Circuit Judge, Jones and Green, District

Judges.*

Order

The Motion of N.A.A.C.P., New York City Region of

New York State Conference of Branches, et al., to Alter

the Judgment of the Court in this action, entered April 12,

1972, denying their Motion to Intervene as party defen

dants and granting plaintiff New York State’s Motion for

Summary Judgment, having come before the Court at this

time; and having considered the memoranda, affidavits

* G r e e n , District Judge, did not participate in this decision.

4a

Judgment of the District Court

and exhibits submitted in support of the Motion to Alter

Judgment, the Court enters the following Order pursuant

to Local Rule 9 (f), as amended January 1, 1972.

Wherefore, it is this 25th day of April, 1972.

Ordered: That the Motion of N.A.A.C.P., et al., to Alter

the Judgment of the Court in this action be and the same

is hereby denied.

/ s / E dward A llen T amm

Circuit Judge

/ s / W illiam B. Jones

District Judge

5a

Notice of Appeal

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

D istrict of Columbia

Civil Action No. 2419-71

New Y ork S tate, on behalf of New York, Bronx,

and Kings Counties,

Plaintiff,

—against—

U nited S tates o f A merica,

Defendant,

N.A.A.C.P., etc., et al.,

Applicants for Intervention.

N otice of A ppeal

To the Supreme Court of the U nited States

Notice is hereby given that the N.A.A.C.P., New York

City Region of New York State Conference of Branches,

Antonia Vega, Simon Levine, Samuel Wright, Waldaba

Stewart and Thomas R. Fortune, applicants for interven

tion in the above mentioned action, hereby appeal to the

Supreme Court of the United States from the final order

entered in this action on April 13, 1972, denying applicants’

application for intervention and granting a declaratory

judgment in favor of the plaintiff and the final order

entered in this action on April 25, 1972, denying applicants’

motion to alter judgment.

This appeal is taken pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §1973b(a).

6a

Notice of Appeal

Jack Greenberg

Jeffry A. M intz

E ric S chnapper

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Telephone: 212-586-8397

W iley B ranton

500 McLachlen Bank Building

666 Eleventh St., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

Telephone: 202-737-5432

Counsel for Appellants

7a

APPENDIX B

In the U nited States D isteict Court

F ob the D istrict of Columbia

Civil A ction No. 2419-71

Memorandum o f the United States

New Y ork State on behalf of New Y ork, B ronx and

K ings Counties, political subdivisions of said State,

Plaintiff,

v.

U nited States of A merica,

Defendant.

Defendant’s M emorandum ano A ffidavit in Response to

Plaintiff’s M otion for S ummary Judgment

Based on the facts set forth in the affidavits attached to

plaintiff’s Motion for Summary Judgment and the rea

sons set forth in the attached affidavit of David L. Norman,

Assistant Attorney General, the United States hereby con

sents to the entry of a declaratory judgment under Section

4(a) of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (42 U.S.C. 1973 b (a )).

David L. N orman

Assistant Attorney General

Civil Rights Division

8a

D istrict of Columbia,

City of W ashington,

David L. N orman, having been duly sworn, states as

follows:

My name is David L. Norman. I am Assistant Attorney

General, Civil Eights Division, Department of Justice.

I make this affidavit in response to the plaintiff’s Motion

for Summary Judgment in the case of New York State v.

United States of America, Civil Action No. 2419-71, United

States District Court for the District of Columbia. I am

familiar with the Complaint filed by the plaintiff and with

the Answer filed by the United States herein.

Following the filing of the Complaint, the United States,

pursuant to the requirements of Section 4(a) of the Voting

Eights Act of 1965, as amended (42 U.S.C. 1973b(a.)),

undertook to determine if the Attorney General could con

clude that he has no reason to believe that the New York

State literacy test has been used in the counties of New

York, Bronx and Kings during the preceding 10 years for

the purpose or with the effect of denying or abridging the

right to vote on account of race or color, and thereby con

sent to the judgment prayed for. At my direction, attor

neys from the Department of Justice conducted an investi

gation which consisted of examination of registration rec

ords in selected precincts in each covered county, interviews

of certain election and registration officials and interviews

of persons familiar with registration activity in black and

Puerto Eican neighborhoods in those counties.

I have reviewed and evaluated the data obtained through

this investigation in light of the statutory guidelines set

forth in Section 4(a) and (d) of the Voting Eights Act of

Affidavit o f the Assistant Attorney General

9a

1964 (42 U.S.C. 1973b (a) and (d)). In my judgment the

following facts are relevant to the issue of whether the

New York literacy test “has been used during the ten

years preceding the filing of [this] action for the purpose

or with the effect of denying or abridging the right to vote

on account of race or color” and to the question of whether

the Attorney General should determine “ that he has no

reason to believe” that the New York literacy test has been

used with the proscribed purpose or effect:

1. New York presently has suspended all requirements

of literacy as a condition of registration and voting as re

quired by the 1970 Amendments to the Voting Rights Act.

Our investigation revealed no allegation by black citizens

that the previously enforced literacy test was used to

deny or abridge their right to register and vote by reason

of race or color.

2. Section 4(e) of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 modified

the New York English language literacy requirements by

providing that the literacy requirement could be satisfied

by proof of attendance through the sixth grade at any

American-flag school, including those in Puerto Rico. This

Act was passed on August 6, 1965 and was finally upheld

by the United States Supreme Court (Katsenbach v. Mor

gan, 384 U.S. 641) on June 16, 1966. Our investigation

indicated that the implementation of this provision through

the use of Spanish language affidavits was not completed

until the fall of 1967.

The supplemental affidavit of Alexander Bassett dated

March 30, 1972, indicates that New York authorities took

significant interim steps to minimize any adverse impact

resulting from the delay in making available Spanish

A ffid a v it o f th e A s s is t a n t A t t o r n e y G en era l

10a

language affidavits. Our investigation did not reveal any

individual citizens whose inability to register is attributable

to the absence of Spanish language affidavits.

3. The 1970 Amendments to the Voting Rights Act

suspended in all jurisdictions any use of literacy tests or

devices. These Amendments were effective on June 22,

1970, and were upheld by the United States Supreme Court

(Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112), in December 1970. Our

investigation included a sampling of registration records

in 21 election districts in the three covered counties. While

there is no evidence that the state continued to require a

foi-mal literacy test after the Act (except in isolated cases),

in each election district examined, a significant percentage

of those registration applications examined after June

1970 bear a notation that some proof of literacy was

recorded.

The supplemental affidavit of Alexander Bassett indi

cates that New York authorities took reasonable steps to

notify all registration workers of the suspension of all

literacy requirements and that notations of proof of literacy

resulted from either (a) obtaining such proof contingently

in the event the courts ruled in New York’s favor in the

challenge of the literacy suspension or (b) isolated in

stances where individual registration officials continued to

obtain literacy contrary to official instructions.

Based on the above findings I conclude, on behalf of the

Acting Attorney General that there is no reason to believe

that a literacy test has been used in the past 10 years in

the counties of New York, Kings and Bronx with the

purpose or effect of denying or abridging the right to vote

on account of race or color, except for isolated instances

A ffid a v it o f th e A s s is t a n t A t t o r n e y G en er a l

11a

Affidavit of the Assistant Attorney General

which have been substantially corrected and which, under

present practice cannot reoccur.

David L. N okman

Assistant Attorney General

Civil Eights Division

Sworn to and subscribed

before me this 3rd day

of April 1972

Notary Public

My commission expires

M E IIEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C « $ S ^ > 219