Affidavit of Frank C.J. McGurk Filed by the Defendants

Public Court Documents

August 19, 1969

13 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Alexander v. Holmes Hardbacks. Affidavit of Frank C.J. McGurk Filed by the Defendants, 1969. 6271ac21-cf67-f011-bec2-6045bdffa665. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/41628199-708c-4f12-8d1c-df01b807e05e/affidavit-of-frank-cj-mcgurk-filed-by-the-defendants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

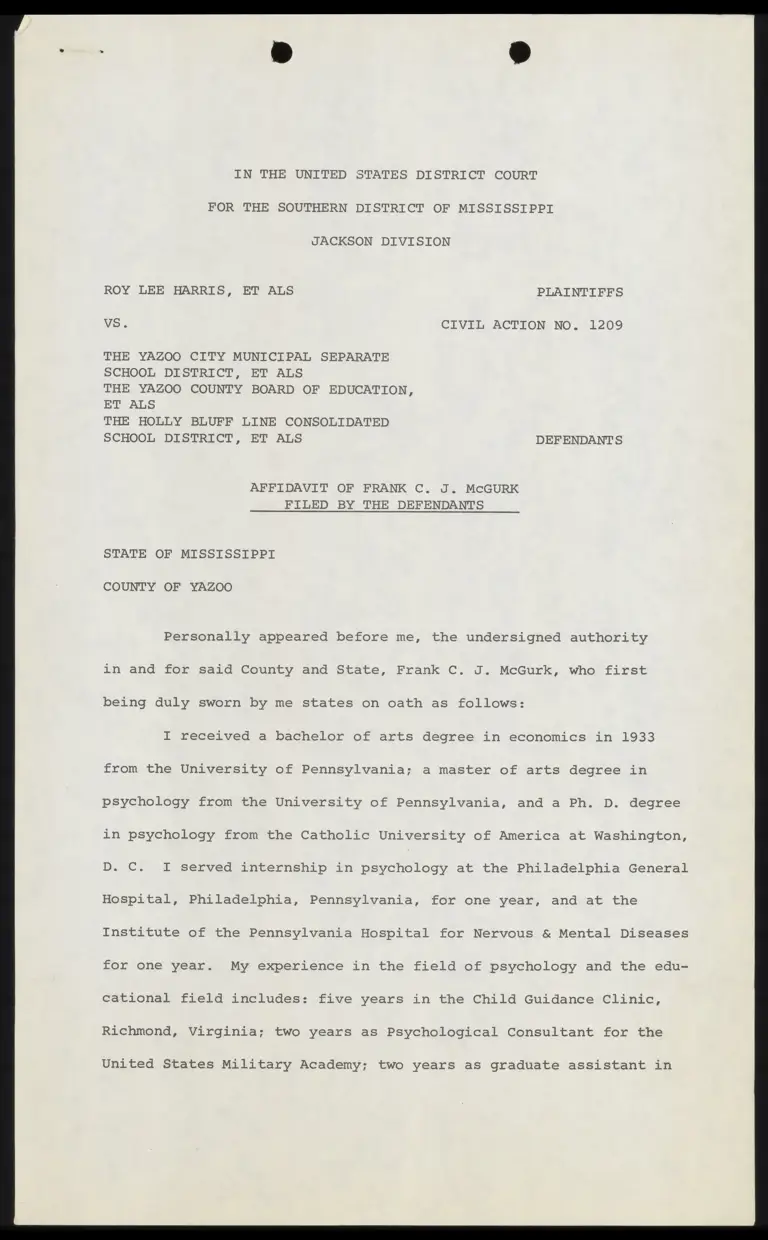

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

JACKSON DIVISION

ROY LEE HARRIS, ET ALS PLAINTIFFS

VS. CIVIL ACTION NO. 1209

THE YAZOO CITY MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET ALS

THE YAZOO COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

ET ALS

THE HOLLY BLUFF LINE CONSOLIDATED

SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET ALS DEFENDANTS

AFFIDAVIT OF FRANK C. J. McGURK

FILED BY THE DEFENDANTS

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

COUNTY OF YAZOO

Personally appeared before me, the undersigned authority

in and for said County and State, Frank C. J. McGurk, who first

being duly sworn by me states on oath as follows:

I received a bachelor of arts degree in economics in 1933

from the University of Pennsylvania; a master of arts degree in

psychology from the University of Pennsylvania, and a Ph. D. degree

in psychology from the Catholic University of America at Washington,

D. C. 1I served internship in psychology at the Philadelphia General

Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for one year, and at the

Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital for Nervous & Mental Diseases

for one year. My experience in the field of psychology and the edu-

cational field includes: five years in the Child Guidance Clinic,

Richmond, Virginia; two years as Psychological Consultant for the

United States Military Academy; two years as graduate assistant in

economics at the University of Pennsylvania; five years as instruc-

tor to assistant professor of psychology at LeHigh University,

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania; six years at Villanova University as asso-

ciate professor of psychology; and seven years at Alabama College,

Montevallo, Alabama, as professor of psychology.

I am a member of the American Institute of Medical Climatology,

the American Psychological Association and the Alabama Psychology

Association. Articles and studies prepared by me which have been

published include Performance of Negro and White School Children in

Richmond, Virginia, 1941; Performance of Negro and White High School

Children on Culturally and Nonculturally Weighted Questions, 1951;

Socio-Economic Status and Psychological Test Performance, 1953;

Negro Performance on Culturally Weighted Test Questions, 1953;

Scientist's Report on Race Differences, 1954; Negro Versus White

Intelligence - An Answer, 1960; Psychological Effects of Ionized

Air, 1961; Ionized Air and Post-operative Pain, 1962; various book

reviews.

I have dare tilly reviewed the proposed order filed in this

matter by the Yazoo city Municipal Separate School District together

with the affidavit of Harold C. Kelly, Superintendent of such Dis-

trict; the proposed order filed in this matter by the Yazoo County

Board of Education and the affidavit of W. C. Martin, County Super-

intendent of Education of Yazoo County, and the proposed order filed

in this matter by the Holly Bluff Line Consolidated School District

and the affidavit of Joel Hill, Superintendent of Schools of such

District. In connection with this affidavit I have considered the

recitation of facts set forth in the affidavits of such Superinten-

dents but have not considered the expressions of opinions therein

contained.

For the past twenty or twenty-five years it has been my

considered opinion that the use of psychological tests for classify-

ing children for teaching groups is a more sensible, more objective,

and more scientific way of teaching than any other known plan. As

far as the literature on grouping is concerned, both capacity tests

and achievement tests have been used at one time or another and

discussed thoroughly in the psychological literature. It is neces-

sary, however, in understanding this dichotomy to know precisely

what is meant by each of these two types of tests, and to determine

from this knowledge what each type of test will do when used to

separate children into homogeneous teaching groups.

A capacity test represents an attempt at making a prediction

about what a child will do, or a group of children will do, some

time in the future. For example, if one is said to have an I.Q.

of 140, the prediction would be that such a child will have little

difficulty in going through the usual school curriculum, and will

even progress through the most difficult college subjects with

relative ease. Such a child with an I.Q. of 140 is said to be a

genius. On the other hand, a child who has an I.Q. of 90 is regarded

as dull, and the prediction would be that, in the future, he would

have relatively little success with the normal school curriculum.

While the prediction concerning the future of a child with an I.Q.

of 140 is very, very much better than the prediction concerning the

future of a child with an I.Q. of 90, the vital factor is that the

result is a prediction. This is a technical matter and needs no

discussion here.

An achievement test, on the other hand, is not a prediction

about the future. If a child has a reading score of 22, and a

reading score of 22 is the average, or median, score obtained by

children who are half way through the fourth grade, it is found

that the child's score of 22 is the normal, or the norm, score for

grade 4.5. If a child has a reading score of 40 and this is the

average score attained by children three-quarters of the way through

the fifth grade, it is found that the child's score of 40 is the

normal score of children who are in grade 5.8 or thereabouts. An

achievement test represents what someone can do at the present time --

at this moment, right now -- a prediction is not involved.

Suppose that at the beginning of the fourth grade the average

number of questions answered correctly on a reading test is 12.

This represents the norm for grade 4.0, i.e., the very beginning of

grade 4. To know that a child has a score of 12 does not enable

anyone to make any prediction about what the child will have at the

end of the fourth grade, or at the beginning of the fifth grade, or

at the end of his school career. Later achievement tests will de-

termine what the child can actually do when the tests are given.

In this sense, then, capacity tests, which are predicters of the

future, are completely different from achievement tests, which are

objective measures of the present.

I should like to emphasize the achievement test as an objec-

tive measure of the present. No one makes any evaluative judgment

about whether a child answers well or poorly on an achievement test;

if a child gets twelve questions correct, he scores 12. If he gets

twenty questions correct, he scores 20. Scores of 12 are translated

into grade equivalents by means of norms published by the testmaker,

a score of 20 is translated into grade equivalent by the same table

published by the testmaker, and whether or not the tester or the

local school authorities like or dislike the result does not enter

into the matter. Thus, when the tests are administered and scored

by disinterested people, these tests are as objective as any charac-

teristic of education can be.

Let me refer again to the fact that for the past twenty or

twenty-five years I have advocated the use of these tests to classify

children in elementary and secondary schools. Such achievement tests

administered through an outside, disinterested testing agency as

here proposed is extremely desirable. There will be no question

what the capacity of each child is; the question here is simply

whether this child, for whatever reason, can be said to have a read-

ing ability, or an arithmetic ability, or this or that or the other

kind of ability required for such and such a grade.

This means that socio-economic status, or what is commonly

called disadvantaged status, is of no consideration in understanding

achievement tests. It does not matter whether the child had no

chance to learn before, whether he has been held back before,

whether any other retarding circumstance has operated on him before,

a child who otherwise should be in the sixth grade and who is read-

ing at the fourth grade level is objectively retarded. This child

needs help. And furthermore, this child needs help at his achieve-

ment level, and not at somebody else's grade level. Therefore it

is important that such a child be placed in a school situation that

is within his ability to perform. With this kind of placement, his

performance and advancement into the future can be regarded more

brightly than with any other kind of performance. It is important

to understand that past or present socio-economic status plays no

part in the describing of a child as being advanced or retarded in

any school subject, such as reading, any more than it plays in de-

scribing a child as advanced or retarded in another school subject,

such as mathematics or science or German or social studies, etc.

The recognized and generally accepted psychological authorities

find that when children are grouped according to their ability, learn-

ing is faster for the children. The teaching routine is considered

easier for the teacher because there is a narrower band of abilities

for her to cover. Because the proposed plan is to administer the

achievement tests each year, there is the further advantage that any

improvement made by the child from year to year will be reflected in

his achievement test score and this will, in turn, cause him to ad-

vance in placement according to his improvement in school achievement.

Thus, if a child starts out in one of the slower groups because of

his present achievement and shows considerable progress between now

and next year, he will be placed in one of the higher groups next

year. As he improves from one year to the next, he will be placed

higher and higher and higher and the possibility is that he might

even reach the highest of the achievement groups. There is no

known way for this to happen except by use of some objective achieve-

ment standard such as is demonstrated by achievement test scores.

It is to be emphasized that the use of achievement tests does not

segregate children except by achievement and that these achievement

groups are fluid, and can change, and will change, from year to

year according to the child's progress. This places the

responsibility for improving on the child and, as is noted by

several writers in the literature, the use of achievement grouping

improves motivation to learn.

A further very important advantage to be considered regard-

ing achievement tests is that it does not place a child who is not

advanced in achievement in a competitive situation that he cannot

handle. Without achievement testing it is perfectly possible for

a child whose achievement is low to be placed with a group of chil-

dren whose achievement is high. Such a child, in such a position,

is bound to be unhappy and this unhappiness, in turn, acts on his

emotional life. This, in its turn, reduces his motivation and re-

duced motivation means further lack of school achievement. With

the use of achievement tests, as is proposed here, it is foreseen

that such a series of undesirable circumstances will be eliminated

from the schools.

It has been a question for a number of years about how well

a teacher can teach a group of children who range widely in ability.

There is no evidence in the psychological or educational fields

that slow children, or those who have achieved little, can learn

simply by being in the presence of bright children. It is my opinion

and also thatof psychologists and educators that a child's learning

is directly related to the amount of effort that can be expended in

his direction by his teacher. This amount of effort is determined

partly by the range of achievements of the pupils in the class that

the teacher is teaching. If this range of abilities be great, the

amount of teaching directed at the slow-learning child will have

to be small, considering all members of the class. By grouping

children according to their achievement test scores, the teacher can

cover a large group of low achievers at the time she is properly

teaching one child, which will make for greater teaching efficiency.

In other words, if a teacher has a group of thirty children, ten of

whom are low achievers, she cannot spend much time with them if she

is also to teach to the average child and the superior achievers.

However, if the class is one of thirty equally low achievers, all

thirty will receive instruction at their level for the entire class

period. At the same time, by placing the high achieving children

in a group, the teacher can teach to their abilities with the same

efficiency with which she teaches to the low achievers. With the

same kind of effectiveness, the average achievers can also be handled.

Many of these principles are covered in the publication by

the United States Office of Education, Department of Health, Educa-

tion, and Welfare, in a 1966 report numbered OEO 20089, and entitled

Survey of Research on Grouping as Related to Pupil Learning. The

authors are Jane Franseth and Rosemary Koury. This article states

clearly that slow pupils were better learners when placed in homoge-

nous classes (page 9). The same report notes that superior children

make better use of enrichment materials, which means that if superior

children and under-achievers are classified in the same group, the

difference between the two groups of children and the use they make

of materials is bound to be quite noticeable. The authors, sensing

this, comment, "When a child is with others who accept him and re-

spond to him, that is, others with whom he wants to associate, he

can contribute more and function better in the group” (page 13).

The same article recites that both superior achievers and slow

achievers show better attitudes toward the teacher when grouped in

homogeneous groups (page 14). Moreover, low ability children are

found to have better attitudes toward school when grouped by

achievement (page 14).

The presence or absence of low achievers in the group is

also discussed in this work, where it is stated that having hetero-

geneous groups (which include both gifted and the slow) does not

improve either the gifted or the slow. It is found that the gifted

child in the group affects the other children who are very bright

or gifted but otherwise has no effect on the children who are slower

(page 22). Furthermore it was reported that the presence of slow

children in a group had a consistently upgrading effect on other

children in the group in arithmetic only, but had no other effects

at all (page 22); it is found that in homogeneous classes, gifted

children achieve better than in heterogeneous classes (page 22).

It is further found that the presence of gifted children does not

improve the achievement of lower groups of children (page 22, column

l, paragraph 4).

Actually, there is no factual basis for the often-remarked

"bad effect" of grouping upon personality. In a study conducted by

outstanding educators, found to be such by the United States Office

of Education in the above publication, it was found that grouping

does not create anxiety among the children; on the contrary, it is

inferred that the effects of grouping actually increase motivation

when children who have a tendency to get anxious about school are

put in their appropriate achievement group, and children who have

very high achievement without anxiety are separated into their own

achievement group. Thus, personality is important in grouping, but

i w

it has no deleterious effect; separating children by personality

improves their motivation, improves their learning, and reduces,

rather than increases, anxiety (page 30). My opinion is the same

as the above quoted conclusions contained in such Survey.

It is important that not one of the studies included by

the United States Office of Education in this Survey of Research

has shown that grouping has any deleterious effect on children.

It is worth pointing this out clearly in view of the unfounded com-

ments that grouping is undemocratic.

Grouping is discussed by the National Education Association

in a publication entitled Research Summary 1968 - Ability Grouping.

This Research Summary covers 102 studies of grouping by ability of

various sorts (achievement and otherwise) and it is significant that

97 of these 102 studies find no evidence that ability grouping is

detrimental to the children. In five of the studies there were

comments about detrimental effects, but they were completely un-

supported by any objective evidence. There is considerable evidence

contained in the NEA Research Summary that teachers find homogeneous

grouping desirable as a teaching technique, and no evidence is pre-

sented to the contrary.

In the NEA research report there are comments in favor of

ability grouping based both on I.Q. and on achievement. Some of

the authors cited by NEA preferred to group children by intelligence,

even though this has been criticized by other writers. Numerous

authorities find hak ability grouping through the use of achieve-

ment tests is more effective for slow learning children, and others

emphasize the importance of such ability grouping for the gifted

child. Any type of ability grouping is found to be useful on both

types of children. Over and over again these reports reveal that

=10~

J u

teachers have greater success with homogeneous ability groups;

there is not one comment, not one piece of research, noted in

which the teachers found this teaching technique to be undesirable.

It should be quite clearly pointed out to the Court that, on occa-

sion, a writer has commented that ability grouping is undemocratic

and detrimental to personality but, in such cases, no evidence

whatsoever is presented in support of these generalities.

Among the recent researchers whose work is presented in sum-

mary form by the NEA, the above findings previously attributed to

the Office of Education publication are confirmed. Achievement

grouping does not harm children, either in their learning or in

their personalities. Teachers like the technique, and it appears

to effect in the children desirable attitudes toward both teacher

and school. Learning is enhanced both for fast and slow learners.

As was pointed out previously, only five of 102 studies were ad-

versely oriented toward homogeneous grouping of children.

The two studies just commented on, the Survey of Research on

Grouping as Related to Pupil Learning, and the NEA Research Summary

called Ability Grouping, were sources of secondary information in

which I summarized the findings reported by the Office of Education

and the National Education Association. In a personal review of

the authorities in the psychological and educational fields which

I performed recently, the same findings recur. In the period be-

tween 1029 and 1967, thirty-three studies were reported in the

Psychological Abstracts, which is a service supported and supervised

by the American Psychological Association under which a very large

share of all of the studies published in psychology and related

wl]

fields are made available to researchers in summarized form. By

the rules laid down by the American Psychological Association,

the abstracts which appear in Psychological Abstracts are required

to be free of the abstractor's bias and to represent an objective

presentation of the content of the studies abstracted.

Accordingly, I searched the Psychological Abstracts for the

period mentioned above, except for the years 1934, 1935, 1948, 1949

and 1962. The Abstracts for these years were not available to me.

Of the thirty-three articles which were published in that time

period, only two mentioned any disadvantageous results from group-

ing by ability (and again, these articles covered ability grouping

from the point of view of both intelligence testing and achievement

testing). The thirty-three articles presented included descriptions

of ability grouping used in this country, in Germany, in Austria,

in Great Britain, and in Brazil. Thus, ability grouping, such as

that proposed in the plans submitted here, is not a restricted pro-

cedure; it is internationally known, and widely respected. The

articles published in this period include studies made in small

school districts and large city schools. From those that included

only thirty to forty children in one class, the studies ranged to

those which included 500 experimental children, and the general

agreement among all of these studies was that ability grouping is

educationally useful and organizationally desirable. The findings

in my personal survey confirmed those previously described as con-

tained in the NEA research and the Office of Education research.

Not only has ability Grouping been determined useful as a teaching

technique by the teachers but it has also been determined useful

-l2w

4 s

in teaching both bright and dull children. There is no evidence

in my survey or in any other source that grouping has any bad ef-

fects on personality.

I have studied the plans included in the proposed orders

described in my affidavit in the light of my training, experience

and examination of the authorities mentioned in this affidavit and

the general authorities in the fields of psychology and education

applicable here. It is my professional opinion as a psychologist

that grouping by ability, as in these cases by the use of the achieve-

ment test scores mentioned in the plans or other similar nationally

recognized tests, is desirable from an educational viewpoint, will

be extremely helpful to the school children and to the schools as

educational institutions and will also accomplish the policy of the

courts to bring about the mixing of all children in the classrooms

without regard to race, and particularly the mixing of children of

the white and Negro races without regard to previous patterns of

attendance of schools and without any effect from a previously

practiced dual system of schools related to the races.

Ze

SWORN TO and subscribed before me this the /Z — day of

August, 1969.

flop Tr (Cr, vi

Notary Public J

=13-