McGhee v. The Nashville Special School District Memorandum

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McGhee v. The Nashville Special School District Memorandum, 1969. dc2d9590-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4178a874-b5fb-4947-a00f-94e3b37fcba7/mcghee-v-the-nashville-special-school-district-memorandum. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

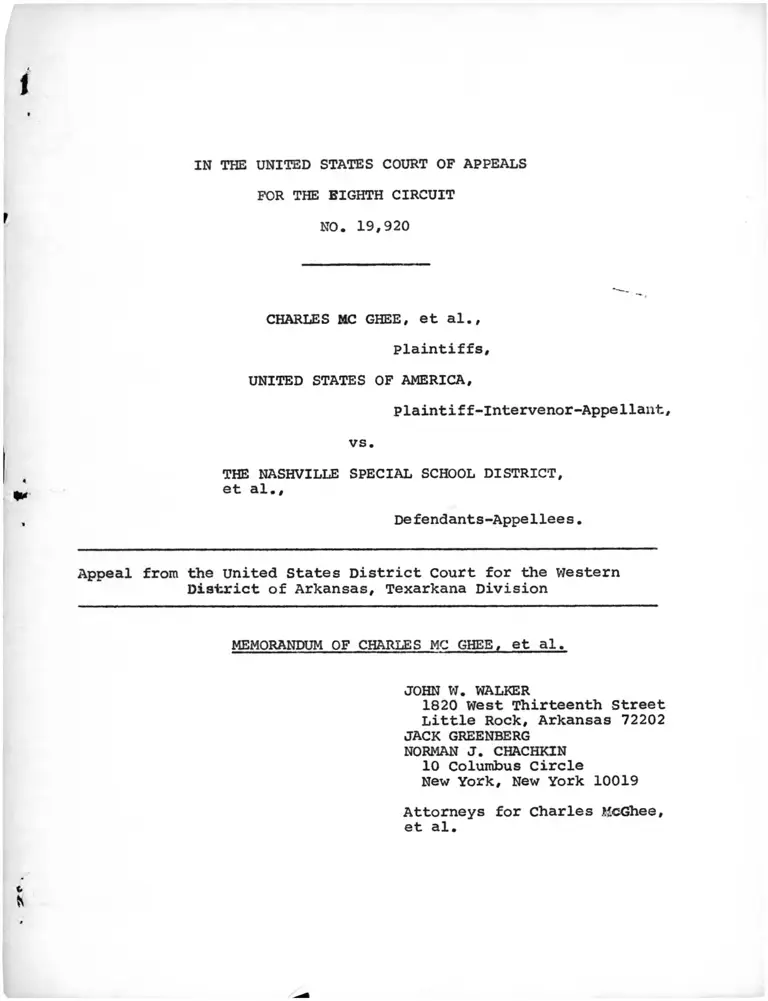

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NO. 19,920

CHARLES MC GHEE, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

plaintiff-lntervenor-Appellant,

vs.

THE NASHVILLE SPECIAL SCHOOL DISTRICT,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the united States District Court for the Western

District of Arkansas, Texarkana Division

MEMORANDUM OF CHARLES MC GHEE, et al.

JOHN W. WALKER

1820 West Thirteenth Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72202

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Charles McGhee,

et al.

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NO. 19,920

CHARLES MC GHEE, et al..

Plaintiffs,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellant,

vs.

THE NASHVILLE SPECIAL SCHOOL DISTRICT,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Western

District of Arkansas, Texarkana Division

MEMORANDUM OF CHARLES MC GHEE, et al.

This Memorandum is filed on behalf of Charles McGhee, et al.,,

who are formal parties to this appeal although not technically

"interested" in this appeal. The original plaintiffs in this

action wish to state their position to the Court, however, and in

particular to emphasize two points not covered in the Brief of the

United States: (1) the need for uniformity in Arkansas school

desegregation cases; and (2) the effect upon this case of the

decision in Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., ____ U.S. ____

(1969), rev'q sub nom. United States v. Hinds County Bd. of Educ.,

_____ F.2d ____ (5th Cir. 1969).

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

Plaintiffs Charles McGhee, et al., adopt the Statement of

the issues contained in the Brief of the United States.

STATEMENT

Plaintiffs adopt the Statement of facts contained in the

Brief of the United States.

ARGUMENT

Plaintiffs agree with most of what is said in the Brief of

the United States. This case, involving some five school districts,

is a particularly instructive example of failure by both the

school boards and the courts to achieve the dismantling of the

dual system of schools.

The two school systems involved in this litigation were

classic examples of one of the devices used to maintain segregated

schools: dual overlapping zones. In each case, the dual zones were

contiguous with district boundary lines. The Nashville-Childress

system consisted of two totally overlapping school districts, one

for whites and one for Negroes. The Saratoga-Mineral Springs-

Howard County Training School system consisted of two separate

white districts and a Negro district which totally overlapped the

1/

two white districts.

This Court has recently had before it districts which used

the other major segregation-perpetuating methods: a single

district operating district-wide white and Negro schools

(Jackson v. Marvell School District No. 22, ___ F.2d ___ (8th

Cir. 1969)); and separate non-overlapping districts for white

and Negro students (Haney v. County Bd. of Educ. of Sevier

County, 410 F.2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969)).

- 2 -

in 1954, the Supreme Court of the United States held in

Brown v. Board of Bduc„, 347 U.S. 483, that the maintenance of

separate educational facilities for white and Negro students,

through whatever device, was unconstitutional. Subsequently, in

Brown II, 349 U.S. 294 (1955), the Court decreed that while school

boards had an obligation to begin immediately the process of

converting to unitary school systems, it would be the responsibility

of the district courts, where school districts were challenged in

litigation, to determine whether valid reasons existed to justify

the rate at which a district was proceeding with its constitutional!

imposed task. The history of school desegregation law since that

time has largely been one of decisions by appellate courts urging

faster accomplishment of the goal, culminating in the October 29,

1969 decision of the United States Supreme Court in Alexander v.

Holmes County Bd. of Educ., supra. That decision reflects the

frank recognition that the procedural framework established in

Brown II, as well as the standard of "all deliberate speed,"

had failed to bring about compliance with the Fourteenth Amendment.

After the 1954 Brown decision, none of the districts here

involved took any action to comply with the Constitution. Cf.

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 431 (1968).

Not until this suit was filed on December 20, 1965, did any prospect

for change appear. The proceedings in this litigation demonstrate,

however, that the actions of the district court have been

inconsistent and they have failed to achieve the constitutional

objective.

3

In the case of the Nashville and Childress districts,

the district court found Childress to have been unconstitutionally

created as a separate Negro school district, ordered its

dissolution and the education of its students by the Nashville

district with consolidation of school facilities, not freedom

of choice. But in the case of the Howard County Training School

District, which the court below likewise found illegally created,

the court required only that upon its dissolution, students

formerly attending its schools (despite their residence within

the physical boundaries of either the Mineral Springs or

Saratoga districts) be given freedom of choice to attend either

the white or black school, predictably, the Negro school operated

previously by the Howard County Training School District remained

all Negro.

4

Even after the decision in Green, supra, the district

court refused to face the reality of a situation graphically

shown by the map in the government's brief. But for race, the

Howard County Training School would never have been built and

operated. Its continued operation as an all-Negro facility

cannot be justified under Green.

The district court's decision is even less justifiable

under Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., supra. The effect

of the delay granted by the Fifth Circuit in that case was to

permit thirty Mississippi school districts to continue to use

freedom of choice plans which had produced results no more signif

icant, certainly, than the results of freedom of choice in

Saratoga-Mineral Springs. The Supreme Court held that the continued

operation of such plans, because of supposed administrative obstac

les to the implementation of other plans, for any additional

period of time, was totally indefensible under the Constitution.

In order to assure meaningful relief, the Supreme Court also

described the new responsibilities which it expected the Courts of

Appeals to assume to make certain that unitary school systems were

achieved at the earliest possible date.

Alexander means, therefore, in the context of this case,

that this Court has a responsibility when this case comes before it

to determine whetle r or not freedom of choice can be justified as

a matter of law, based on the latest information about the school

district (see United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

Dist.. 406 P. 2d 1086, 1092 n.6 (5th Cir. 1969)), and to prescribe

a remedy which will immediately carry out the constitutional

mandate. This will require specific directives from this Court

to the district court on remand.

There is an additional reason for specific directions

in this Court's mandate. Uniformity of approach to Arkansas school

desegregation cases, within the limits imposed by the differing

facts of each school district, is much to be desired. So long as

inconsistent positions are taken by the courts, other school

districts and school administrators will have difficulty in defining

their constitutional obligations. This district court has shown,

in this very litigation, an inconsistent approach to similar

2/factual situations. We think it appropriate, therefore, that

this Court specifically order the immediate formulation and imple

mentation of a plan to replace freedom of choice in Saratoga and

Mineral Springs, so that there will be no question of the obligation

of the district courts or of school boards in this respect in the

future.

2/ The same district judge in Jackson v. Marvell School District.

supra, first held freedom of choice unacceptable and then,

eight months later, ruled that the school district would be permittee

to use it.

-6-

CONCLUSION

Plaintiffs Charles McGhee, et al., for the foregoing

reasons, support the relief requested by the United States in this

case in its Brief previously filed.

Respectfully submitted,

JOHN W. WALKER

1820 West Thirteenth S

Little Rock, Arkansas

72202

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

Attorneys for Charles

McGhee, et al.

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I mailed copies of the

Memorandum of Charles McGhee, et al. to counsel for all

parties by United States mail, postage prepaid (two

copies each) as follows:

Boyd Tackett, Esq.

State First National Bank Building

Texarkana, Arkansas 75501

Herschel H. Friday, Esq.

1100 Boyle Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

Hon. Joe Purcell

Attorney General of Arkansas

Justice Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72202

John A. Bleveans, Esq.

United States E^jartment of Justice

Washington, D. C. 20530

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

I

-8-