Brief and Appendix for Appellants

Public Court Documents

November 16, 1972

43 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Brief and Appendix for Appellants, 1972. 9dbd2ddd-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/41b92328-d339-4bb7-b6ea-bb257569a339/brief-and-appendix-for-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

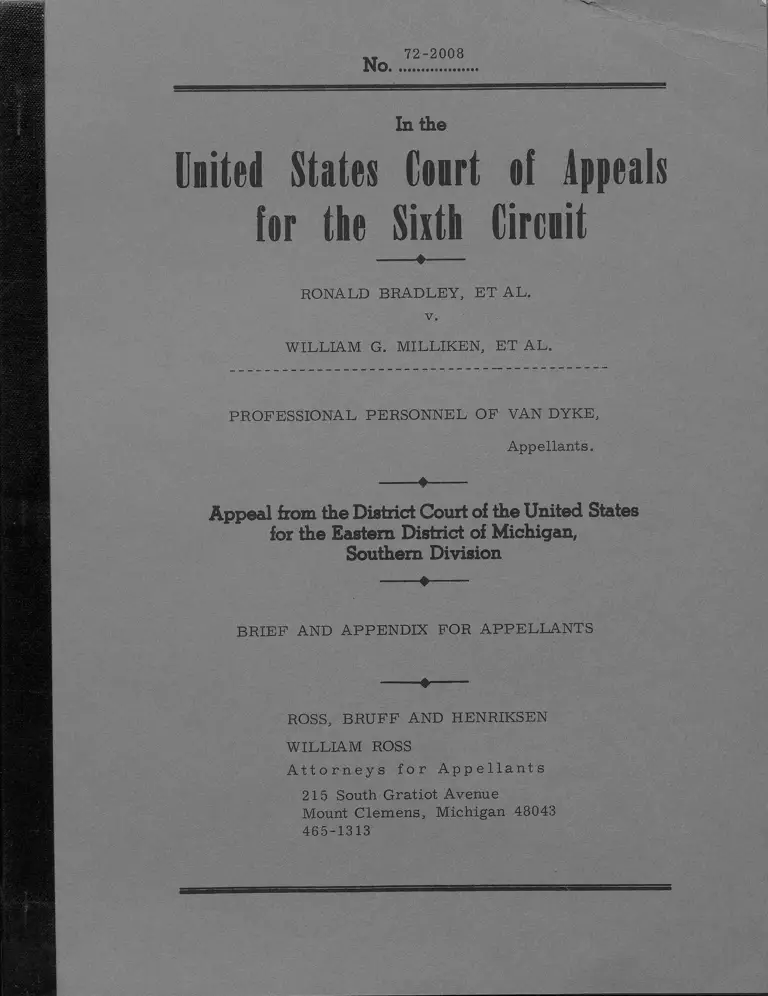

72-2008

No.

In the

Uiited States C urt ef Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit

r—♦—

RONALD BRADLEY, ET AL.

v,

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, ET AL,

PROFESSIONAL PERSONNEL OF VAN DYKE,

Appellants.

— — —

Appeal from the District Court of the United Slates

lor the Eastern District of Michigan,

Southern Division

V ... -

BRIEF AND APPENDIX FOR APPELLANTS

— — ~

ROSS, BRUFF AND HENRIKSEN

WILLIAM ROSS

A t t o r n e y s f o r A p p e l l a n t s

215 South Gratiot Avenue

Mount Clemens, Michigan 48043

465-1313

r

Offset printing by Carl J. Pitt

1044 Penobscot Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

(313) 961 -9177

i

f*

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

V

3

4

r -D

6

1

8-

9

0

.1

o

• «

"i«>

. J

l

Pages

T A B L E O F CO N TEN TS O F B R IE F

Table of Authorities ....................................................................... i

Statement of Issue ........................................................................ iii

Table of Contents of Appendix ...................................................... iv

Statement of the Case .................................................................... 1

Summary .................................................. 4

Argument ................................................................................ 4

Conclusion ............................................... .................................... . 17

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES:

Bennet v Madison Board of Education,

437 F2 554 5th Cir (1970)..................................... 10-12

Layne-New York Co. v Allied Asphalt C o.,

53 F, R.D, 529, U. S. Dist. Ct. W. D. Penn

(1971) ............................................................................. 16

Moore v Tangipahoa Parish School Board,

298 FS 288, U. S. Dist. Ct. E. D. New Orleans

(1969) at page 292 ......................................................... 9-10

Oliver v School District of Kalamazoo,

448 F2 635, (CA6, 1971)..................................... 8-9

Smith Petroleum Service, Inc. v Monsanto Chemical

Co., 420 F2 1103 (CA 5, 1970) at page 1115 . . . 13

Smuck v Hobson, 408 F2 175,

(Dist. of Col, District, 1969)........................ 5-7, 7-8, 12

Textile Workers Union of America v Allendale,

226 F2 765 (Dist. of Col. Cir. 1955).................... 13-16

T A B L E O F A U TH O R ITIE S

Pages

OTHER AUTHORITIES:

2 Barron & Holtzoff,

Federal Practice and Procedure, P. 201 ................. 4

Federal Rule 24(a) and (b ) ........ (cited throughout b rie f.)

MCLA 423.211 3

STATEMENT OF ISSUE PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

IN A LAW SUIT CONCERNING SCHOOL DESEGREGATION

IN WHICH THE TRIAL JUDGE FINDS AS A FACT THAT

THE SCHOOL DISTRICT IS UNCONSTITUTIONALLY SEG

REGATED, IN WHICH THE TRIAL COURT ORDERS INTER

DISTRICT TRANSFER OF BOTH PUPILS AND TEACHERS,

SHOULD HE PERMIT THE EXCLUSIVE BARGAINING

AGENT FOR THE TEACHERS OF ONE SUCH DISTRICT,

TO INTERVENE IN THE PROCEEDINGS?

.IV

T A B L E O F C O N TE N TS O F A P P E N D IX

3

5

Relevant Docket Entries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Motion of Professional Personnel of Van Dyke (The exclusive

bargaining agency of the Board of Education of the Van Dyke

Public Schools), Robert Paul; Josephine Galia, Gary W.

Pierce^ Max B. Harris, Florence Crawford and Doris E.

Labbe, As Class Representatives to Intervene As Party-

Defendants . o

Pages

la

O -9 # 9 '9 <t ® kC C 2a

6

.7

3

9

TO

11

12

13

Brief in Support of Motion for Leave to Intervene by

Professional Personnel of Van Dyke, Robert Paul,

Josephine Galia, Gary W. Pierce, Max B. Harris,

Florence Crawford and Doris E. Labbe e » a < «> • «

Conditions of Intervention submitted by Professional

Personnel of Van Dyke . , 9 *

Ruling and Order on Petitions for Intervention . * • 0 «S .«* & *>

Petition for Re-Hearing of Motion of Professional Personnel

of Van Dyke, et al.

Brief in Support of Petition for Re-Hearing of Motion of

Professional Personnel of Van Dyke for Leave to Intervene

As Party Defendants . . . .

5a

6a

7a

1 la

* 9 9 * w -9 a 13a

j a

16

17

IB

19

20

Answer of Intervening Defendant, Detroit Federation of

Teachers to Petition for Rehearing of Motion of Professional

Personnel of Van Dyke, et a l., to Intervene...........................

Rulings and Order on Motions and Other Matters Heard

June 14, 1972 9 « f » ■» <* e 9 * 9 9 9 » 9 9

14a

16a

o t If

J 1 jj

23

24

No.

72-2008

In the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circiit

-- ----— -

RONALD BRADLEY, ET AL„

WILLIAM G. MILLXKEN, ET AL.

PROFESSIONAL PERSONNEL OF VAN DYKE,

Appellants.

—♦...... -

Appeal from the District Court of the United States

for the Eastern District of Michigan*

Southern Division

—— -

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

PROFESSIONAL PERSONNEL OF VAN DYKE

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is a school desegregation case. The plaintiffs are

black school children attending schools within the jurisdiction of the

Board of Education of the City of Detroit, all parents having school

children within such district and the National Association for the

1

2

3

4.

5

6

7

Oo

9'

10

11

1.2

13

14.

15

16

14

18

1 QCi v

20-

21

9-v

.& < s,A

23

24

25

S t a t e me n t o f the Case

2

Advancement of Colored People. The original defendants are William

G. MxXliken, Governor of the State of Michigan, Frank J. Kelley,

Attorney General for the State of Michigan, Michigan State Board of

Education,and the Board of Education of the City of Detroit.

Quite early in these proceedings The Detroit Federation of

Teachers Local 231, American Federation of Teachers, AFL-CIO and

the Citizens Committee for Better Education were granted permission to

\!i\

\

intervene.

When it became apparent that the trial court, after finding |j

IIii

de facto segregation in the Detroit School system, contemplated ordering

a metropolitan plan for desegregation, which envisioned the transfer of

both students and teachers inter districts (so-called Metropolitan Plan),

• ■ - .

several school districts that would be affected by such finding and order,

filed motions for intervention. These motions were granted. (App. 16a)

Likewise, white school children attending schools in the affected school f

districts and an association known as TRI-COUNTY CITIZENS FOR ji

; . |

INTERVENTION IN FEDERAL SCHOOL ACTION NO- 35257 were granted

permission to intervene. (App. 16a) j

. ■; |

However, the two collective bargaining agencies of school

■ ’ • ' • j

districts affected - - the Michigan Education Association, and the appellant jj

herein - - were denied such right. (App. 16a) j

All of the defendants, original and intervening have filed |

!!Notices of Appeal before this Court and oral argument has been had on j|

j!I!such appeals. j!: / l!

The movant to intervene, appellant herein, an independent j

S t a t e me n t ©f the Case

3

(i. e« unaffiliated) collective bargaining unit, is the exclusive bargaining

agent for the teaching personnel of the Van Dyke School District, having

been so elected under the appropriate statutes of the State of Michigan

(MCLA 423.211),, As such exclusive bargaining agency it has entered

|

into Master Agreements with the School District of Van Dyke, The

v • , v ■ \

Master Agreements cover the salaries, fringe benefits and general

working conditions of the teaching personnel of the School District of

Van Dyke,

itThe School District of Van Dyke is in southeastern Macomb

1County (northeast of Wayne County), It lies between Eight Mile Road

H i 1 . | i H i H i | . jf

and Ten Mile Road as its southerly and northerly boundaries, respec

tively, and between Sherwood and Schoenherr Avenues as its easterly

and westerly boundaries, respectively.

: 11

{

.2 f

I

3

!

M I

1 1

I ]

7 1I

f

n- !

” !

10 I

SI

1

1.2 I

2

14

15

11

i f

! 8

19

J j j

21

22

25

** ,*£

25

4

SUMMARY

In a school desegregation case, in which the trial judge finds

de facto segregation In which such trial judge contemplates massive inter

school district transfer of students and teachers, the exclusive bargaining

agent for one such school district has a right to intervene under Federal

Civil Rule 24 a (2), or in the alternative, it is an abuse of discretion not

to permit such movant to intervene under Federal Civil Rules 24b,

ARGUMENT

Even prior to its liberalizing 1966 amendment, Federal Civil

Rule 24 was to be construed broadly. The rule is liberally construed

in the light of earlier decisions regulating federal intervention practice

which the rule amplifies and restates. 2 Barron & Holtzoff, Federal

Practice and Procedure, P. 201. [West Publishing Co. (1950) and cases

therein cited. ]

Rule 24 states:

Upon timely application, anyone shall be

permitted to intervene in an action: when the

applicant claims an interest relating to the

property or transaction which; is the subject of

the action and he is so situated that the disposi

tion of the action may as a practical matter

impair or impede his ability to protect that

interest, unless the applicant’s interest is ade

quately represented by existing parties.

It is submitted that the movant-appellant readily and dis-

cernably meet all three requirements of the Rule. Clearly, it has an

interest in an order that may affect its contract of employment with a

school district that becomes a part of a so-called 'Metropolitan Plan. "

i

I j

9 !

\ W {

1 1

f§jj|

7

J j

j

8

■9 j

IQ

1J

12

I

14

15

16

17

IB

19

20

71

22

23

24

■1 ;:i

A r g u m e n t

5

This interest is both professional and economic. Professional, in that

it would desire and seek the best possible "mix" of both students and j

|

teachers. Economic, in that it would hope that its contractual relation -

j

ships with the Van Dyke School District would be respected and enforced

by the trial court,

In Smuck v Hobson, 408 F2 175, Dist. of Co. District jj

— — — — - |

(I960), a school desegregation case, in which the parents of white children

moved to intervene [after the involved school district had determined not

to appeal the trial court's findings] that Court wrote at page 178:

|

As the trial judge pointed out in his decision

to grant intervention to the parents, under the

pre -amendment cases the task of defining what j

constitutes an "interest” was typically "sub- j

sumed in the questions of whether the petitioner

would be bound or of what was the nature of his j

property interest, " The 1966 amendments j

were designed to eliminate the scissoring ef

fect whereby a petitioner who could show "in

adequate representation" was thereby thrust j

against the blade that he would therefore not

be "bound by a judgment, " and to recognize |

the decisions which had construed "property"

so broadly as to make surplusage of the adjec

tive. In doing so, the amendments made the

question of what constitutes an "interest" more

visible without contributing an answer. The

phrasing of Rule 24(a)(2) as amended parallels

that of Rule 19(a)(2) concerning joinder. But

the fact that the two rules are entwined does

not imply that an "interest" for the purpose of

one is precisely the same as for the other,

The occasions upon which a petitioner should j

be allowed to intervene under Rule 24 are not

necessarily limited to those situations when :

the trial court should compel him to become a j

party under Rule 19. And while the division

of Rule 24(a) and (b) into "intervention of j

Right" and "Permissible Intervention" might l

superficially suggest that only the latter in- j:

volves an exercise of discretion by the court, |!

Argu.rn.ent

the contrary is clearly the case,

The effort to extract substance from the con-

elusory phrase "interest" or "legally protect

able interest" is of limited promise, Parents

unquestionably have a sufficient "interest" in

the education of their children to justify the

initiation of a lawsuit in appropriate circum

stances, as indeed was the case for the plain

tiff-appellee parents here. But in the context

of intervention the question is not whether a

lawsuit should be begun, but whether already

initiated litigation should be extended to in

clude additional parties, The 1966 amend

ments to Rule 24(a) have facilitated this, the

true inquiry, by eliminating the temptation, or

need for tangential expeditions in search of

"property" or someone "bound by a judgment, "

It would be unfortunate to allow the inquiry to

be led once again astray by a myopic fixation

upon "interest, " Rather, as Judge Leventhal

recently concluded for this Court, "[A] more

instructive approach: is to let our construction

be guided by the policies behind the 'interest5

requirement, * * * [T]fae 'interest' test is

primarily a practical guide to disposing of

lawsuits by involving as many apparently con-

cerned persons as is compatible with efficiency

and due process, " (Emphasis added)

The decision whether intervention of right

is warranted thus involves an accommodation

between two potentially conflicting goals: to

achieve judicial economies of scale by resolv

ing related issues in a single lawsuit, and to

prevent the single lawsuit from becoming

fruitlessly complex or unending, Since this

task will depend upon the contours of the parti

cular controversy, general rules and past deci-

sions cannot provide uniformly dependable

guides. The Supreme Court, in its only full-

dress examination.of Rule 24(a) since the

1966 amendments, found that a gas distrib

utor was entitled to intervention of right

although.its only "interest" was the economic

harm' it claimed would follow from an allegedly

inadequate plan for divestiture approved by the

Government in an antitrust proceeding. While

conceding that the Court's opinion granting

1

o«£j

v>

5

1

7

8

i

3C

11.

12

.13

14

15

16

If

18

19

20

2 i

22

23

24

25

A r g u m e n t

7

intervention in Cascade Natural Gas Corp.

y, El Paso Natural Gas Co. "is certainly sus- j

ceptible of a very broad reading, " the trial j

judge here would distinguish the decision on the

ground that the petitioner "did show a strong,

direct economic interest, for the new company

[to be created by divestiture] would be its sole

supplier. " Yet while it is undoubtedly true j

that "Cascade should not be read as a carte

blanche for intervention by anyone at any time, "

there is no apparent reason why an "economic

interest" should always be necessary to justify

intervention. The goal of "disposing of law- j

suits by involving as many apparently concerned

persons as is compatible with efficiency and due

process" may in certain circumstances be met

by allowing parents whose only "interest" is

the education of their children to intervene.

Hence, the movant-appellant has an interest, most direct

and immediate, in the type of Metropolitan Plan adopted by the court, if

one is adopted. (It should be noted that the movant-appellant did not

desire intervention to oppose the findings made by the trial court relative

to the de facto segregation in the Detroit School system or to its proposed

remedies for such segregation.) (App. 6a) jf:

A second facet of Federal Rule 24 is that the "disposition j

; IH;

of the action may as a practical matter impair or impede [the inter-

venor’s] ability to protect that interest. " Again, in a case of this nature,}

litigated over a long period of time and at great expense, appealed many

■

times and at many levels and which will probably, finally be appealed jj

i I

by the parties to the United States Supreme Court, the movant-appellant g

H]f

will either have his day in Court now or never. As the Court in Smuck jj

If||

v Hobson, supra, said at P. 180: J

Rule 24(a) as amended requires not that the |

applicant would be "bound" by a judgment in the jj

1 1

2

3

4

if

6

7

8

0

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

. 18

19

20

21.

22

23

24

21

A r g u.m e n t

8

action, but only that "disposition of the action

may as a practical matter impair or impede his

ability to protect that interest, " In Nuesse v.

Camp this Court examined a motion by a state

commissioner of banks to intervene under the

new Rule 24 (a) in a suit brought by a state bank

against the United States Comptroller of Cur

rency, The plaintiff claimed that the defendant

would violate the National Bank Act if he approved

the application of a national bank to open a new

branch near the plaintiff’s office, The inter -

venor feared an interpretation of the statute which

would stand as precedent in any later litigation

he might initiate. The Court, agreeing, con

cluded that "under this new test stare decisis

principles may In some cases supply the prac

tical disadvantage that warrants intervention as

of right, "

The third requirement under Federal Rule 24 is that the

j

interests of the movant not be adequately represented by any of the

parties. Once more, this is true in the instant matter, The Detroit

Federation of Teachers, itself an intervener, is the exclusive bargaining j

agency of the school teachers of the Detroit School Board, It has

national affiliations. It is large, On the other hand, the movant- j|

appellant is a small independent exclusive bargaining agency of a rela

tively small school district outside of the Detroit area and outside of jII

Wayne County, Moreover, the Detroit Federation of Teachers has never

made the claim that it can represent the interests of the movant-appellant.

!

It should be noted that this court, in Oliver v School j]

|f

District of Kalamazoo, 448 F2 635 Sixth Cir Ct of App (1971), in a

per curiam opinion, permitted the following organizations to intervene i

I

in a school desegregation case: Kalamazoo City Education Association, j

|

The Michigan Education Association* The National Educational Association,

i

jj

vj

4

*j

6

%

a

s

10

11

12

13

14.

15

1 8

i?

IB

19

20

21

22

23

24

2 5

A r g u.m e nt

9

The League of Women Voters of Michigan, and the Kalamazoo Area League

of Women Voters,

The interest of the movant-appellant. Professional Personnel j

of Van Dyke, in the instant litigation is at least as great as that of the

organizations permitted to intervene in Oliver y Kalamazoo, and

probably much greater.

If, arguendo, the movant-appellant does not have the right to j

intervene under Federal Rule 24 (a), it should be permitted to intervene

under Federal Rule 24 (b)» The trial court in Moore v Tangipahoa j

Parish School Board, 298 FS 288, US Dist Ct E„ D0 New Orleans

(1969) wrote at page 292:

Alternatively, both applicants seek per

missive intervention under Rule 24 (b), which

provides in part:

I

"Upon timely application anyone may be

permitted to intervene in an action: * * *

(2) when an applicant’s clainr or defense f

and the main action have a question of law j

or fact in common, * * * In exercising

its discretion the court shall consider

whether the intervention will unduly delay

or prejudice the adjudication of the rights

of the original parties, "

Rule 24(b) should be liberally construed,

Western States Machine Co, v, S. S.

Hepworth Co, , E. D.,N. Y, , 1941, 2 F. R. D.

145, ” [B]asically, * * * anyone may be

permitted to intervene if his claim and the

main action have a common question of law

or fact, " unless the court in its "sound dis -

cretion [determines that] * * * the inter

vention will unduly delay or prejudice the !

adjudication of the rights of the original j

parties, Allen County School Board of Prince

Edward County,'supra 28 F„ R, D9 at 363, j

I

o

w

4

5

6

7

8

9

.1.0

11

12

.13

14

||

1,6

il

ia

u

20

21.

22

23

24

2 0

It is beyond dispute that the claims of the

white students and parents of Tangipahoa

Parish are based on common questions of law

and fact with the issues raised in the main

action. Nor can it be denied that, as a

practical matter, the applicants have an im

portant interest in the outcome of this liti

gation, All students and parents, whatever

their race, have an interest in a sound educa

tional system and in the operation of that sys -

tern in accordance with the law.

It is the opinion of the appellant, that in a public interest type |j

of case, such as school desegregation matter, broad spectrums of points

of view should be encouraged by the courts - not rejected. The dissent- I]

ing opinion of Circuit Judge Wisdom in Bennet y Madison Board of

I fj

Education, 437 F2 554 5th Cir (1970) is overwhelming. In that cause, j; — “— ——“

the National Education Association sought intervention in a desegregation

matter brought by private citizens (as here). Judge Wisdom found that

the Association had a right under Section 24 (a) of the rule, and alter-

• , rInately, it was an abuse of discretion by the trial court under Section (b)

fj

of the rule to not permit intervention.

Judge Wisdom wrote on Page 556, (and the identical problem jH

will face the Court in improvising a Metropolitan Plan in the instant .

action):

NEA represents a very real interest in these

school desegregation cases -- that of its members

who are black teachers in these school districts.

These teachers will be directly affected by the

actions of the court and the school board in

carrying out the disestablishment of the dual jl

school systems. The decision of this Court in j|

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School jj

District, 5 Cir. 1970, 419 F.2d 1211 (en banc), jj

requires that the racial ratio of teachers in jj

each school be the same as that in the system as jj

10

A r g u.m e n t

A r g u.m e n t

a whole. Practical problems exist in shifting

to such a system. With the changing racial

compositions of schools,, there must necessarily

be some replacement of black administrators

with white administrators, causing the loss of

important positions within the educational

hierarchy. Additionally, many school sys

tems must decrease their teaching staffs and

administrative personnel because of shrinking

student bodies. (Emphasis added)

NEA also meets the second test of Rule

24(a)* being nso situated that the disposition

of the action may as a practical matter impair

or impede [its] ability to protect" its interests.

In theory a second suit by NEA would not be

barred by res judicata -- the standard for inter

vention before the 1966 Amendments -- though

its outcome might be affected by stare decisis.

See Atlantis Development Corp. v. United

States* 5 Cir. 1967, 379 F,2d 818.

And at P. 557:

parties. The courts should handle school

cases as units. This Court implicitly supports

such a practice by evaluating school districts

in terms of all the constitutional requirements

for dismantling a dual school system. See,

e .g . , United States v. Jefferson County Board

of Education, 5 Cir. 1966, 372 F.2d 836,

aff’d en banc, 1967, 380 F„2d 385; Singleton

v. Jackson, supra. There are sound reasons

for such a practice. The types of discrimina

tion which a school boardmust abjure and undo

are inherently interrelated. For instance,

desegregation of student bodies cannot be sep

arated from faculty desegregation. Planning

for the latter depends on methods used to

accomplish the former: which schools5 racial

composition will be changed; whether any schools

will be closed altogether; whether a decrease

in the total size of the public school student body

should be planned for. We know, for example,

that when formerly black schools are integrated,

there may be a move to replace black admini

strators with whites. We know also that when

black schools are closed as part of the deseg

regation process - - which occurs more frequent

1

A r g urn e n t

12

5 1

6

i f

8 1

9 5}

1 A i V

is iifiIj

1 •: 1 A \ .i> : {

I

<*•? '■A i.

23

24.

25

than the closing of white schools - - the jobs

of black faculty and staff are jeopardized.

Students have an interest in learning from a

desegregated faculty.

In the context of mapping future plans - -

students, faculty, facilities, and extracur

ricular activites must be considered in the over

all changeover. NEA may help courts avoid

repetitious and inefficient litigation. The

fundamental policy of Rule 24, to encourage

simultaneous adjudication of related claims,

is the same policy that underlies the practice

of considering together all school desegrega

tion issues.

Judge Wisdom also found that no existing party could r e

present the interest of the teachers "The private plaintiffs, students and

?!i|

11 |j their parents, cannot be taken to represent adequately the interests of

12 I the teachers. Students are more interested in student desegregation.i|

13 :• Their interest in fair treatment of teachers is clearly less direct than

h

14 jj that of teachers themselves, "

||; : JJfS A • 1; A A . . gAAv A-1 5 A'A '% 1 A iArlAA/ ' A- A

Under Rule 24, petitions to intervene must, of course, be

timely. Timeliness is to be considered under all the surrounding cir -̂

cumstances. The movant-appellant, as soon as it determined that it

18 i; may be involved in a Metropolitan Plan of desegregation, moved for inter-

| j

19 ;i vention. Prior to that time, it clearly had no interest in the litigation.| j | i

20 It offered to accept the previous findings of the Court (App 6a). It

was most interested in submitting evidence and having its professional

3 Si :

22 || conclusions considered by the court in teacher placement and terms of

employment as well as in placement. In no way would the granting

of its petition to intervene have delayed the trial or inconvenienced the

court or the then party litigants. Smuck v Hobson, infra held that

I

2

<■>•j

4:

5

6

7

8

9

.10

11

12

13

14

3 5

11

Il

ls

19

20

21.

22

23

24

2 5

A r g u.m e n t

13

that Petition to Intervene even after final judgment is not untimely. (P 18&)

A most complete discussion, on "timeliness!f is contained in

Smith Petroleum Service, Inc. v Monsanto Chemical Co, 420 F2 1103 1

5th Cir (1970), at R 1115:

It is true, of course, that an application for

intervention, whether as a matter of right or per

missive, must in every case be timely; Rules

24(a) and 24(b) provide for intervention "upon

timely application. " See 2 Barron & Holtzoff,

Federal Practice and Procedure § 594, at 364

(Wright ed. 1961); 3B Moore, Federal Practice

3T 24.13, at p. 24-521 (2d ed. 1969). The deter

mination as to whether an application to inter

vene is timely, however, is a matter within the

sound discretion of the trial court. [Citing cases]

Moreover, "[W]hether an application for inter

vention is timely does not depend solely upon the

amount of time that may have elapsed since the

institution of the action, although of course that

is a relevant consideration. " [Citing cases]

The trial court may take into account all the

circumstances of the case, including any c ir

cumstances contributing to delay in the appli

cation for intervention. [Citing cases]

Furthermore, it has been suggested that "the

most important factor" which should be considered

by the trial court "is whether any delay in mov

ing for intervention will prejudice the existing

parties to the case. " 2 Barron & Holtzoff,

supra, § 594, at 366.

Finally, movant-appellant would cite two cases, other than

school desegregation cases, that illustrate the liberal attitude, a practical

attitude rather than a doctrinaire one, of the courts as regards Federal

Rule 24. !|

One pre-dates the 1966 amendment, the intent of which was j

1to yet further "liberalize" the rule. In Textile Workers Union of jj

America v Allendale, 226 F2 765 Dist of Col Cir (1955), the plaintiff, jj

A r g u me n t

14

manufacturing goods for sale to the United States, brought the action to

review a determination of the Secretary of Labor fixing nation-wide mini

mum wages. A union of employees as well as a competing manufacturer

sought to intervene. Their motions were denied by the trial court.

The Court of Appeals reversed, saying on Page 767 of 24(a):

In conventional litigation, one is bound by

a judgment in the action, within the meaning

of Rule 24(a), when the judgment is res judi

cata as to him. Appellants in this case were

not parties in a technical sense to the adminis

trative proceeding; nevertheless they are

"bound" by the determinations therein in a very

practical sense. Authoritative rulings made in

this proceeding fixed a wage at a national level.

These rulings are under attack in the suit for

review below. It is true that, if the attack

succeeds, the final judgment would preclude

neither the appellants nor the appellees from

later pressing their interests at the adminis

trative level. But ultimate victory at that

point cannot overcome the "practical disad

vantage" to which appellants may be subjected

as a result of the prior judicial action, For

example, if the determinations are upset, the

membership of the appellant union will be

deprived of economic benefits. That the union

may subsequently receive other benefits from

new determinations which it may procure can

not compensate for the losses suffered in

the interim. Nor does the fact that the union

may bargain for a wage higher than the mini

mum convince us that it and its members are

not bound, in a practical sense, by minimum

wage determinations. Similarly, if the

appellant-employer is forced out of business

by an injunction restraining the effectuation

of the wage determinations, he can take little

solace from a subsequent moral victory.

Hence we think that the strict test of res judi

cata is inappropriate in applying Rule 24 (a)

to the present case.

Ii

i f

And on P age 768:

'1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

IS

14

1S

16

17

.1 8

3 9

20

21.

22

23

24

25

A r g u.m e n t

Generally "a claim of an absolute right to

intervene must be based upon the language of

Rule 24 (ah " But this rule is not "a com

prehensive inventory of the allowable instances

for intervention" as of right. Missouri-Kan

sas Pipe Line Co. v. United States, 1967

312 U. S. 502, 505, 61 S. Ct. 666, 85 L. Ed.

975. In that case, in reversing an order

denying intervention, the Supreme Court

was not concerned with the distinction be -

tween 24(a) and (b). In fact the Court spoke

in terms of permissive intervention:

"We are not here dealing with a con

ventional form of intervention whereby an

appeal is made to the court’s good sense to

allow persons having a common interest with

the formal parties to enforce the common

interest with their individual emphasis.

Plainly enough, the circumstances under

which interested outsiders should be allowed

to become participants in a litigation is,

barring very special circumstances, a mat

ter for the nisi prius court. But where the

enforcement of a public law also demands

distinct safeguarding of private interests by

giving them a formal status in the decree,

the power to enforce rights thus sanctioned

is not left to the public authorities nor put

in the keeping of the district court’s dis

cretion. "

In that case, a consent decree specifically

provided for such intervention. But the teach

ing of the case is not so narrowly limited. It

expresses generally the proposition that failure

to come within the precise bounds of Rule 24 's

provisions does not necessarily bar interven

tion if there is a sound reason to allow it.

At Page 77:

Under the circumstances of this case then,

we think the denial of appellants ’ petitions to

intervene exceeded the limits of discretion.

As we said in Wolpe v. Poretsky, appel

lants "have such a vital interest in the result

of [the] suit that they should be granted per-

mission to intervene as a matter of course

' i i

2

<•> ]yj i

4

I

6

7

8

9

10

11

12'

13

14

15

16

11

•1 8

19

20

21

22

23

24

2 5

Ar gujn e nt

unless compelling reasons against such, inter -

vention are shown?7” N(T^uclT*Trcompelling rea-

s°ns" appear here.

The interventions sought here would serve

the ends of justice, They would also promote

judicial and administrative convenience by

avoiding a multiplicity of proceedings and by

bringing to the aid of the tribunal the parties

who "may know the most facts and can best

explain their implications. " (Emphasis added)

Reversed and remanded.

In Layne-New York Co. v Allied Asphalt Co. , 53 F, R„ D, 52 9,

U. S. District Ct. W, D. Penn (1971), the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania^

motion to intervene was granted under both section (a) and (b) of Rule 24.

The suit was a patent infringement cause, involving a process for sealing J

off abandoned mines. It based its motion for intervention on the thrust

that if the patents were sustained "the bidding process in this area will

be seriously chilled" P, 530.

The Court went on to say:

. . . Of paramount importance in this case, we

consider the public interests of the people of

Pennsylvania in this matter, Pennsylvania

suffers peculiar damage by reason of a large

number of abandoned coal mines whose run offs

cause a great amount of pollution in the streams

of the Commonwealth, We well understand the

Commonwealth’s apprehension as to the effect

of a decision upholding the validity of this

patent upon bidding processes for future con

tracts in this area.

If this intervention were denied, the Common

wealth might well institute a separate suit again

st this plaintiff or successive contractors would

be met by similar litigation. It is in the high

est public interest to solve this situation.once

and for a ll, in these, so far as we can as

certain, the first suits which have raised these

questions, W e:w i l l therefore allow-the inter

vention.

17

CONCLUSION

Ijj

It is gainsaid that the primary question in the instant matter jjI f If Ifis of great public importance. It may very well be the most noteworthy jj

f!II

of issues of these days; certain it is that it is one of the half dozen most jjIii

noteworthy issues. jjII

Once an order is entered herein that affects the Van Dyke

|f

School District the movant-appellant will be practically foreclosed from jj11 s-l11

litigating its rights in any forum,. Its members may be laid off, trans

ferred, have their salaries reduced, their contractual rights decimated,

have their tenure lost, without any day in court.

1Moreover, whatever court is finally charged with the awe- |

jj

some task of entering the final order in this cause, if such plan calls jj

- l|ilfor cross-districting busing, it would be deprived of valuable expertise j

jjthat the movant-appellant would be able to muster to assist that court. jj

If

The trial court's Order (App. 16a) denying tne movant- jj

P

appellants motion to intervene should be reversed, subject to reasonable jj

conditions (those contained in such order and applicable to the inter- jj

1• U- - Isvenors permitted to intervene). I■’ IS- - ■, ■ - , - . •.••• ■ I!

Respectfully submitted, jj

jj

ROSS, BRUFF & HENRIKSEN f?!

WILLIAM ROSS |

Attorneys for Appellants Professional

Personnel of Van Dyke

ff

215 South Gratiot Avenue

Mount Clemens, Michigan 48043 jj

465-1313

Dated: November 16, 19 72.

Appendix

j

1 1

2 I

•j

4

S

6

7

|

9

lO-

l l

12

13

14

15

16

17

II

19

20

21

22

23

24

2 5

l

A P P E N D I X

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

Ronald Bradley, et aL

vs,

William G. Milliken, et al.

No, 35257

Professional Perssonnel of Van Dyke,

Appellants

1972

Feb, 22

Apr, 11

Apr, 2 5

CA6 No, 72-2008

RELEVANT DOCKET ENTRIES

Motion of ProfessionalPersonnel of Van Dyke (the exclusive

bargaining agency of the Board of Education of the Van

Dyke Public Schools), Robert Paul, Josephine Galia,

Gary W. Pierce, Max, B, Harris, Florence Crawford

and Doris E. Labbe, as class representatives to intervene

as party defts. with brief and proof of service, filed.

Hearing Feb, 22/72

Petition for re-hearing of motion of Professional Personnel

of Van Dyke, Robert Paul, Josephine Galia, Gary W.

Pierce, Max B» Harris, Florence Crawford and Doris

E» Labbe, for leave to intervene as party defts, with

brief and proof of service, filed.

Answer of intervening deft. Detroit Federation of Teachers to

petition for rehearing of motion of Professional Personnel

of Van Dyke, et a l., to intervene and proof of service, filed

June 29 Rulings and order on motions and other matters heard June

14/72, filed and entered.

2a

MOTION OF PROFESSIONAL PERSONNEL OF VAN DYKE

(The exclusive bargaining agency of the Board of «

Education of the Van Dyke Public Schools),

ROBERT PAUL, JOSEPHINE GALIA, GARY W, PIERCE,

MAX B, HARRIS, FLORENCE CRAWFORD and DORIS E.

LABBE. , As Class Representatives to Intervene As

Party Defendants

(Filed Feb. 22, 1972)

NOW COMES the Professional Personnel of Van Dyke,

Robert Paul, Josephine Galia, Gary W. Pierce, Max B. Harris,

Florence Crawford and Doris E. Labbe, by their attorneys ROSS, BRUFF

& RANCILIO, P, C. moving to intervene as party defendants in this

cause and show unto this Honorable Court as follows:

1. That the movant, PROFESSIONAL PERSONNEL OF VAN

DYKE, is the exclusive bargaining agency of the teaching personnel of

the Board of Education of the Van Dyke Public Schools (geographically

located in southern Macomb County), a political subdivision of the State

of Michigan*

2c That the movants, ROBERT PAUL, JOSEPHINE GALIA,

GARY W„ PIERCE, MAX B„ HARRIS, FLORENCE CRAWFORD and

DORIS E. LABBE, are members of the movant, PROFESSIONAL

PERSONNEL OF VAN DYKE, and that they bring this motion on, each

for himself or herself and as members of the movant PROFESSIONAL

PERSONNEL OF VAN DYKE, a group so numerous as to make it im- jj

practicable to bring them all before this Honorable Court* I|

3 c That the movant, PROFESSIONAL PERSONNEL OF VAN

DYKE, as exclusive bargaining agent of the Board of Education of the

Van Dyke public schools, is the signator of a collective bargaining

Motion of Professional Personnel of Van Dyke . . , etc.

3a

agreement with such Board of Education.

4. That the movant, PROFESSIONAL PERSONNEL OF VAN

DYKE has been able to negotiate an exceptionally advantageous collective

■

bargaining agreement for its members, including the individual movants

herein.

5. That the movants are fearful that the party litigants herein

|f

will urge upon this Honorable Court relief that will not sufficiently pro- ii|S

tect these movants in their property rights and human rights as set forth )j

ll

in the Master Agreement between professional Personnel of Van Dyke

and the Board of Education of the Van Dyke Public Schools and their

right to teach in a school of their own choice and to pupils of their own

Itit

choice.

6. That upon information and belief, these movants are the only

ones who have or intend to file a motion to intervene on behalf of a

collective bargaining agency with a school district or on behalf of teachin

personnel of a school district not in the county of Wayne, State of

Michigan.

7. That the rights and obligations are unique to any of the other

party litigants, interveners, or would-be intervenors in this cause..

J8. That upon information and belief some of the party litigants

. • ' ' ■ . I

and intervenors herein have requested relief to be granted them by this I

Honorable Court, which would, be harmful to these movants and not in

their best interests. Moreover, much of the relief requested by the

litigants and intervenors is unconstitutional on its face, j

1

9. These movants have requested concurrence of the attorney

Motion of Professional Personnel of Van Dyke . . . etc.

.4a

for intervenors in this cause, but such has been denied. Moreover, upon!

information and belief, this Honorable Court has determined that it will

decide and determine all Motions for Leave to Intervene.

I

10. This motion is brought on under Rule 24 (b)(2) (Permissive

Intervention), Federal Rules.

11. Individual movants herein move to intervene by reason of

Rule 23 (a)(3) (Class Actions), Federal Rules.

WHEREFORE, these movants request that they be permitted

to intervene in this cause so that they may argue the appropriate relief

to be granted by this Honorable Court in accordance with the determina

tions heretofore made by this Honorable Court.

ROSS, BRUFF & RANCILIO, P. C.

by: s / William Ross______ __________________

WILLIAM ROSS

Attorneys for Movants

215 South Gratiot Avenue

Mount Clemens, Michigan 48043

465-1313

Dated: February 16, 1972

1

!.

■O

<8.:'

y„>

jjj(

a.O

I

7

8

0 -

18

11

12

1.3

j j

1 5.

11

17

3 8

19

20

21

22

23

24

n c

8vs

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE

TO INTERVENE BY PROFESSIONAL PERSONNEL

OF VAN DYKE, ROBERT PAUL, JOSEPHINE GALIA,

GARY W. PIERCE, MAX B. HARRIS, FLORENCE

CRAWFORD and DORIS E. LABBE

Rule 24 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure is as follows;

"(b) Permissive Intervention. Upon timely application

anyone may be permitted to intervene in an action:

(1) when a statute of the United States confer a condi

tional right to intervene; or (2) when an applicant's j

claim or defense and the main action have a question j

of law or fact in common. When a party to an action

relies for ground of claim or defense upon any statute

or executive order administered by a federal or state

governmental officer or agency or upon any regulation, ;

order, requirement or agreement issued or made

pursuant to the statute of executive order, the officer

or agency upon timely application may be permitted

to intervene in the action. In exercising its discre- j

tion the court shall consider whether the intervention

will unduly delay or prejudice the adjudication of the j

rights of the original parties. " |

If• • j|

The discretion of the trial court to permit intervention is .

extremely broad. Its application should be liberally construed. j

(2 Federal Practice and Procedure 201). None of the party litigants I

and the intervenors can properly represent these movants. Moreover,

I

these movants may well be helpful to the Court in its determination of -'I

the proper relief to be granted.

Respectfully submitted,: : • ICwSSsm v . A ,fiW, , ; gffSs v m iM e: M0:* ■

ROSS, BRUFF & RANC1LLIO, P.C.

• \II

By: s / William Ross n

WILLIAM ROSS |

Attorneys for Movants ,

215 South Gratiot Avenue

Mount Clemens, Michigan 48043 |j

465-1313 |

Dated: February 16, 1972

*1 1

:? j

i| 5/>

4

Ijm

7

ii

Jjjj ;

10

II

12

13

( j j

i i

16

I f

18:

16

■

2.1

22

23

24

26

CONDITIONS OF INTERVENTION SUBMITTED BY

PROFESSIONAL PERSONNEL OF VAN DYKE

Professional Personnel of Van Dyke, movant for intervention,;;

h■ iiwould suggest the following conditions for intervention, such conditions

J

to be applicable to proceedings on the trial level only:

III

1. Interveners to be bound by the previous findings and con- sim : in i sielusions of the Court,

ft

2, Intervenors to introduce evidence only as to the appropriatene|

of remedy (ies) to be formulated by the Court.

Ross, Bruff and Rancilio

by s / Julius M. Grossbart

Julius M. Grossbart

3400 Guardian Bldg.

Detroit, Michigan

962-6281

ftIS

1

2

o

vj-

4

5'

6

7

8

9

10

] 1

12

IS

14

" 5

16

17

18

19

20

21.

21’-

SS

24

2 5

RULING AND ORDER ON PETITIONS FOR INTERVENTION

IIAt a session of said Court held in the

Federal Building, City of Detroit,

County of Wayne, on this 15th day of

MARCH, A. D. 1972.

PRESENT: HONORABLE STEPHEN J. ROTH

United States District Judge

|

The motion of intervening defendants Denise Magdowski, f|et al. to add parties defendant is continued under advisement, to await

f

further developments in this proceeding. |

Ruling on the motion of the Jefferson-Chalmers Citizens

|

District Council to intervene is continued in accordance with the request

of the movant.

The motions of Allen Park Public Schools, et a l., the

Grosse Pointe Public Schools, the School District of the City of Royal

Oak and the Southfield Public Schools are GRANTED, under Federal

j

Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 24(a)(2) and, in the alternative, under

j

Rule 24 (b)(2), under conditions hereinafter specified.

:|

The motion of Kerry Green, et a l., including Tri-County

Citizens for intervention in Federal School Action No. 3 52 57, is

GRANTED under Rule 24 (b)(2), under conditions hereinafter specified.

j

The intervention of the Tri-County Citizens for Intervention is granted

for the following reasons: (1) The standing of the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People was not challenged by the

original parties to this action; (2) For practical purposes the grant of

intervention to Kerry Green, et al. is a grant of intervention to said

i

organization. The court, for the reasons stated, has not and does not pas

Ruling and Order on Petions for Intervention

on the procedural propriety of either the standing of the NAACP or the

intervention of the citizens' group.

The motion of the City of Warren, a municipal corporation

of the State of Michigan, to intervene, is DENIED, as of right, under

Rule 24 (a)(2), and in the discretion of the court, under Rule 24(b)(2).

The motion of Nancy Bird, et a l., to intervene, is DENIED,

under Rule 24 (a)(2), and under Rule 24 (b)(2), in the discretion of the

court, for the reason that their interests are already adequately repre

sented by the parties, including those to whom intervention has been

granted this day.

The motion of Professional Personnel of Van Dyke, to

intervene, is DENIED, under Rule 24 (a)(2) and, in the discretion of the

court, under Rule 24 (b)(2).

The petitioners who have been denied intervention shall have

a right to appear as amicus curiae.

The interventions granted this day shall be subject to the

following conditions:

1. No intervener will be permitted to assert any claim of

defense previously adjudicated by the court.

2, No intervenor shall reopen any question or issue which

has previously been decided by the court.

3. The participation of the intervenors considered, this

day shall be subordinated to that of the original parties and previous

intervenors.

4. The new intervenors shall not initiate discovery

Ruling and Order on Petitions for Intervention

9a

proceedings except by permission of the court upon application in writing

accompanied by a showing that no present party plans to or is willing to

undertake the particular discovery sought and that the particular matter

to be discovered is relevant to the current stage of the proceedings.

5. No new iniervenor shall be permitted to seek a delay of

' II j

any proceeding in this cause; and he shall be bound by the brief and hearing

schedule established by the court's Notice to Counsel, issued March 6,

1972, j

6. New intervenors will not file counterclaims or cross -

complaints; nor will they be permitted to seek the joinder of additional

parties or the dismissal of present parties, except upon a showing that

such action will not result in delay.

7. New intervenors are granted intervention for two prin

cipal purposes: (a) To advise the court, by brief, of the legal pro

priety of considering a metropolitan plan; (b) to review any plan or

plans for the desegregation of the so-called larger Detroit Metropolitan

area, and submitting objections, modifications or alternatives to it or

them, and in accordance with the requirements of the United States

II

Constitution and the prior orders of this court.

8. New intervenors shall present evidence, if any they

have, through witnesses to a number to be set, and limited, if necessary,

by the court, following conference.

9. With regard to the examination of witnesses, all new

v w k ' \ k \ v k k : ; k k k : k : ; * ; k ; :If

intervenors shall among themselves select one attorney per witness to act

for them, unless one or more of the new intervenors show cause

: 1

M

w

-.5

|

6

7

; 1

9

:

: .14:

|§

18

-19

9 i -*•«

13

K

i f

10 a

Ruling and Order on Petitions for Intervention

otherwise.

These conditions of intervention shall remain subject to

change or modification by the court in the interest of timely disposition

of the case.

DATE: March 15, 1972.

s / STEPHEN J. ROTH

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

1

ov;£

4

5

6

7

o

9

10

f l

12

13

14

15

i ;i

17

18

p 5

20

21

22

23

24

25

1

PETITION FOR RE-HEARING OF MOTION OF

PROFESSIONAL PERSONNEL OF VAN DYKE

(The exclusive bargaining agency of the Board of

Education of the Van Dyke Public Schools),------- _ ■ — “ “

ROBERT PAUL, JOSEPHINE GALIA, GARY W.---------_ — ,j

PIERCE, MAX B. HARRIS, FLORENCE CRAWFORD

and DORIS E, LABBE, FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

AS PARTY DEFENDANTS.

— ------------------------------------------------------------------ ------------------

(Filed April 11, 1972)

Professional Personnel of Van Dyke, petitioner herein, moves

the Court for re-hearing of the denial of its motion for leave to intervene

for the reasons following:

1 „ Professional Personnel of Van Dyke, movant herein, is

the exclusive bargaining agent of the Van Dyke School District. That the

Van Dyke School District is located in Southern Macomb County, State of

Michigan.

i

2. That at the time the Court denied the motion of Profes

sional Personnel of Van Dyke for leave to intervene dated March 15,

1972, the Court had not as yet determined to adopt the so-called

metropolitan plan.

3. That the Professional Personnel of Van Dyke is an inde

pendent and unaffiliated trade union and has negotiated a Master Agree

ment with the Van Dyke School District, which Master Agreement sets

forth the terms of employment between the teaching personnel of the

Van Dyke School District and the said School District.

4. That an important aspect of the Court's final deter

mination in this matter will be its effect on the terms of employment of

Petition fo r Re “Hearing of. Motion to Intervene . . . etc.

.12a

the teaching personnel of the various school districts encompassed by the

Metropolitan Plan.

5. That when only the Detroit School District seemed to be

the school district involved in these proceedings, the Court granted the

application of the Detroit Federation of Teachers for leave to intervene.

6. That the posture and thrust of the intervenor, Detroit

Federation of Teachers, is adverse to that of this movant, Professional

Personnel, of Van Dyke.

7. That this movant has been unable to procure the consent

of the opposition parties.

8. That the interests of Professional Personnel of Van

Dyke can be protected only if its permitted to intervene as a party,

9. That the motion of Professional Personnel of Van Dyke

and its Brief in support thereof is incorporated herein.

WHEREFORE, Professional Personnel of Van Dyke requests

||i!

a re-hearing of its Motion for Leave to Intervene and that it be granted

leave to intervene.

ROSS, BRUFF & RANCILIO, P. C.

By: s / William Ross_____ _____________

WILLIAM ROSS

Attorneys for Movant

215 South Gratiot Avenue

Mount Clemens, Michigan 48043

465-1313

;;fln

Date: April 10, 1972

1

gj

••1

1

6

jflj

8

U

T0.

-il

i . 2 .

It

j j j

j j j

Jji

m

11

5 9

10

21

22;

| ;

24

2 u

13a

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR

RE-HEARING OF MOTION OF PROFESSIONAL

PERSONNEL OF VAN DYKE FOR LEAVE TO

INTERVENE AS PARTY DEFENDANTS

Rule 24 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure is as follows;

n(h) Permissive intervention,, Upon Timely application

anyone may be permitted to intervene in an action: (1)

when a statute of the United States confer a conditional

right to intervene; or (2) when an applicant's claim or

defense and the main action have a question of law or

fact in common. When a party to an action relies for

ground of claim or defense upon any statute or executive

order administered by a federal or state governmental

officer or agency or upon any regulation, order,

requirement or agreement issued or made pursuant to

the statute or executive order, the officer or agency

upon timely application may be permitted to intervene

in the action. In exercising its discretion the court

shall consider whether the intervention will unduly

delay or prejudice the adjudication of the rights of the

original parties. "

The discretion of the trial court to permit intervention is

extremely broad. Its application should be liberally construed. (2

Federal Practice and Procedure 201). None of the party litigants and

the interveners can properly represent these movants. Moreover, these

movants may well be helpful to the Court in its determination of the pro

per relief to be granted.

Respectfully submitted:

ROSS, BRUFF & RANCILIO, P.C.

By: s / William Ross ______

WILLIAM ROSS

Attorneys for Movant

215 South Gratiot Avenue

Mount Clemens, Michigan 48043

465-1313

Date: April 10, 1972

ANSWER OF INTERVENING DEFENDANT, DETROIT

FEDERATION OF TEACHERS TO PETITION FOR

REHEARING OF MOTION OF PROFESSIONAL

PERSONNEL OF VAN DYKE, ET AL. , TO INTERVENE

(Filed April 2 5, 1972)

Now comes Detroit Federation of Teachers, Local #231,

AFT, AFL-CIO, by its Attorneys, Rothe, Marston, Mazey Sachs,

O'Connell, Nunn & Freid, and in answer and opposition to the Petition

for Rehearing on the Motion to Intervene by Professional Personnel of

Van Dyke, avers:

L Answering paragraph 1, intervening defendant admits

the allegations therein, on information and belief,

2, Answering paragraph 2, intervening defendant neither

admits nor denies the allegations of said paragraph, not having sufficient

information on which to base a belief, and leaves Petitioner to its proofs

thereof,

3, Answering paragraph 3, intervening defendant admits

the allegations of said paragraph, on information and belief.

4, Answering paragraph 4, this defendant avers that said

allegations are speculative.

5, Answering paragraph 5, intervening defendant admits

the allegations therein.

6, Answering paragraph 6, intervening defendant neither

admits nor denies said allegations, not having sufficient information on

which to base a belief, and leaves petitioner to its proofs.

7, Answering paragraph 7, intervening defendant denies

15aAnswer of Intervening Defefendant . . . etc.

that it sought such consent, but admits that it would not consent thereto,

8, Answering paragraph 8, intervening defendant denies

said allegations,

9, Said allegations do not state a basis for relief.

In further answer, applicant states no new grounds warranting

intervention in the premises,

WHEREFORE, defendant Detroit Federation of Teachers

prays that such petition for rehearing be denied,

t;

f

Respectfully submitted,

ROTHE, MARS TON, MAZEY, SACHS,

O’CONNELL, NUNN & FREID

by s / Theodore Sachs____________________

Theodore Sachs

Attorneys for DFT

1000 Farmer

Detroit, Michigan 48226

965-3464

DATED: April 21, 1972

5

16a

0

1

8

i

10

!

RULINGS AND ORDER ON MOTIONS AND OTHER

MATTERS HEARD JUNE 14, 1972

At a session of said Court held in

the Federal Building, County of Wayne,

City of Detroit, on the 29th day of JUNE,

A. D, 1972.

PRESENT: HONORABLE STEPHEN J. ROTH

United States District Judge

Hearings were conducted on motions and other matters out

standing as of June 7, 1972 in the above-entitled cause. In addition to J.

|matters listed in the notice dated June 7, 1972, the parties were directed

to call all other matters which were pending and unresolved to the atten

tion of the court; its intention being to put matters in order.

Having considered all matters noticed for hearing and ail

additional matters brought to the attention of the court at such hearing;

IT IS ORDERED:

That the applications of the Grosse Pointe Human Relations

Council, the Michigan Civil Rights Commission, the City of Troy and the

Central United Methodist Church for leave to appear as Amicus Curiae

are DENIED, T'l

The application of the Michigan Educational Association for

leave to appear as Amicus Curiae is GRANTED.

The petition for intervention by the Organization of School

Administrators and Supervisors is DENIED.

Having reheard the petition of the Professional Personnel of

Van Dyke to intervene, the previous denial of its motion to intervene is

I

%

X-

I gj

; 4 .

s'*

4 ..i

§f

|

n. Q

G

T®

jj|

-

1:3

I

■: 1 5

■

St

|f;

;

Ai

p S§

ATw: .W

K

|§|

25

Rulings and Order on Motions and Other Matters Heard 6/14/72

AFFIRMED.

The motion of defendants Magdowski, et al. to add additional

parties defendant was, at the hearing, in effect, withdrawn, and the same

■!!

shall be considered as withdrawn.

The Detroit Board of Education motions to quash certain jj 11

subpoenaes and to strike plaintiffs' plan, and its objections to the state's

' I

metropolitan plans, are each, in view of the state of the proceedings and

||

the issuance of the court's bindings and Conclusions" and "Order for the

Development of Plan of Desegregation, " considered MOOT.

j| . Y.;T c i v v AA ' I : ■ 3 / '5;jl

The Plaintiffs' motions to particularize one of the State

Board's plans and to adjudge the Detroit Board of Education plan legally

insufficient are, in view of the ruling and order referred to in the para”

graph next above, considered MOOT.

Plaintiffs' motion for expenses incurred in the preparation of

its metropolitan plan is held in ABEYANCE pending the filing of

i f f® A -supporting affidavits, if

. l i l f t® :JS S I1 IP ■ R § tfl||M I | | I ® A3® #1|S

Plaintiffs' motions for expenses to be assessed against the

State Board of Education and the Detroit Board of Education, and to j|

require the purchase of transportation equipment are held in ABEYANCE

pending further proceedings.

The disposition of matters above referred to are ORDERED

as indicated and may this day be entered by the Clerk.

DATE: JUNE 29, 1972.

s / STEPHEN 3, ROTH n

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE