Thornburg v. Gingles Supplemental Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1984

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Thornburg v. Gingles Supplemental Brief for Appellees, 1984. 29fe1323-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/42531df7-72a3-4539-a71f-45d7a0f1e345/thornburg-v-gingles-supplemental-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

*,v~

/ «*

DM TH B TJUTTED STATE8 DISTRICT C0T7RTJ~j^

BTERM" DISTRICT OP NOBTH OAK O TjyA ■/

n i SUPPLEMENTAL

'%S%

Julies LbVojtstb Chambwbs . fy-;

Lasi Guxnieb* : t ":^Vi "%

- Pr’NAACP. Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc,.: ..£

. 16th Floor .. •;;=%>

.~ ‘.i'99 Hudson Stre_et _ . -'-'

. New York, New York 10013

- . v(212) 219-1900 . Jv-J ;

x T.uht.tb W crsn sB ' v .

r. - Ferguson, "Watt, Wallas, ; ̂

'and .Adkins, P-A- - .

... f. 951 S. Independence Boulevard

•f ■Charlotte, North. Carolina 28202

(704) 375-8461

Attorneys for Appellees

^•Counsel of Record ■ ; -;

+ h ? [ i K '

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases

Anderson v. City of Bessemer City,

___ U.S. ___ ( 1985) .........

Brooks v. Allain, No. 83-1865

(1984)

1 5

3,15

Hunter v. Underwood,

(1985) ........

U . S .--

• • • •

Pullman-Standard Co. v. Swint, 456

U.S. 273 (198 1 ) ...............

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613

(1982)

Strake v. Seamon, No. 83-1823

(1984) ......................i

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755

(1973) ......................i

Witt v. Wainwright,

(1985) .......

U.S,

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297

(5th Cir. 1973) ..............

14

3,15

9,17

1 5

10

Page

Statutes

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of

1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

S 1 973(b) ........................... 2,7,8

12,15,16,17

*

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965 ............................ 1 6,1 7

Other Authorities

Rule 52, Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure ............................. 3,6

S. Rep. 97-417 ( 1982) 9.10

«

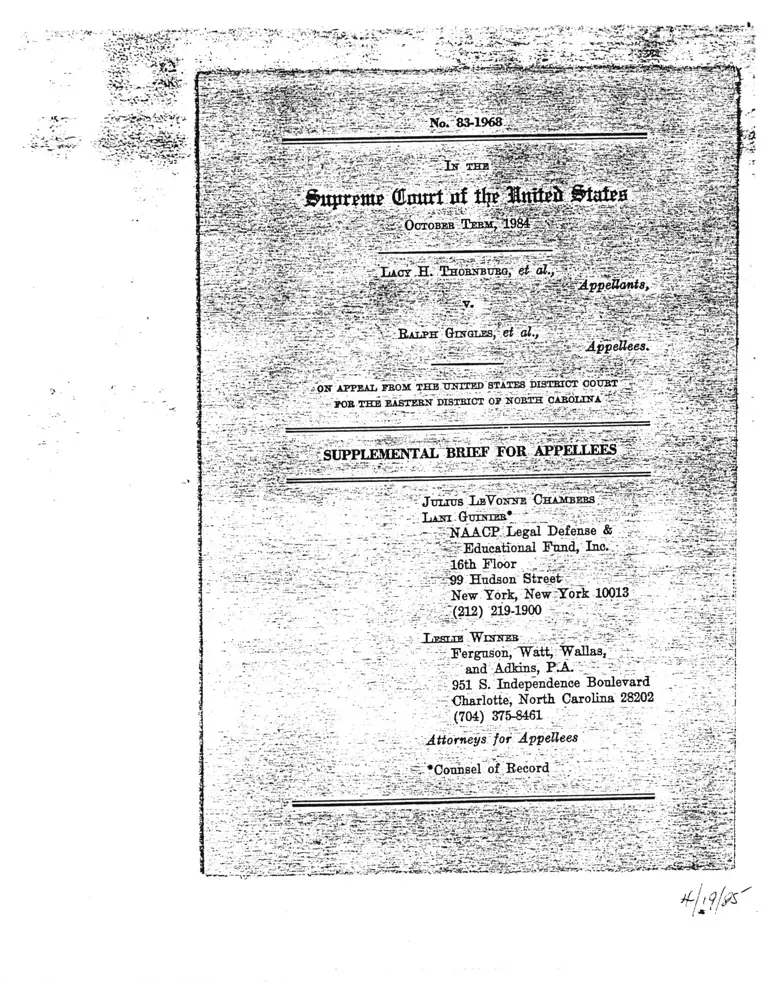

No. 83-1968

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1984

LACY H. THORNBURG, jet al ■ ,

Appellants,

v .

RALPH GINGLES, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States

District Court for the Eastern

District of North Carolina

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

Appellees submit this

Brief in response to the 1

Si" 1 ̂ mental

j by

the United States.

2

The controlling question raised by

the brief of the United States concerns

the standard to be applied by this Court

in reviewing appeals which present

essentially factual issues. A section 2

action such as thi"S requires the trial

court to determine whether

the political processes leading to

nomination or election in the State

or political subdivision are not

equally open to participation by [a

protected group].

The presence or absence of such equal

opportunity, like the presence or absence

of a discriminatory motive, is a factual

question. See Hunter v ■ Underwood,

U.S. ___ (1985); Rogers v. Lodge,

458 U.S. 613 (1982). Correctly recognizing

the factual nature of that issue, this

Court has on two occasions during the

1 42 U .S .C . S 1 973(b).

3

present term summarily affirmed appeals in

section 2 actions. Strake v. Seamon, No.

83-1823 (Oct. 1, 1984); Brooks v, Allain,

No. 83-1865 (Nov. 1 3 , 1 984). If an

ordinary appeal presenting a disputed

question of fact is now to be treated for

that reason alone as presenting a "sub

stantial question," then this case, and

almost all direct appeals to this Court,

will have to be set for full briefing and

argument. We urge, however, that to

routinely treat appeals regarding such

factual disputes as presenting substantial

questions would be inconsistent with Rule

52(a), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

and with the efficient management of this

Court's docket.

The Solicitor General, ha no con

ducted his own review of some portions of

2

the record, advises the Court that, had he

2 The Sol icitor Genera 1, understandably less

4

been the trial judge, he would have

decided portions of the case differently.

The judges who actually tried this case,

all of them North Carolinians with long

personal understanding of circumstances in

that state, concluded that blacks were

denied an equal opportunity to participate

in the political processes in six North

Carolina multi-member and one single

member legislative districts. The

Solicitor General, on the other hand, is

of the opinion that there is a lack of

familiar with the details of this case

than the trial court, makes a number of

inaccurate assertions about the record.

The government asserts, for example,

"there is not the slightest suggestion

that black candidates were elected because

whites considered them "safe". (U.S. Br.

18 n. 17)* 1° fact there was uncontra

dicted testimony that only blacks who were

safe could be elected. (T r . 625-26, 691,

851 857). The Solicitor also asserts,

incorrectly, (U.S. Br. 17 n.14) that the

1982 election was the only election under

the plan in question. In fact, the

districts have been the same since 1971.

(J.S. App. 19a)

5

equal opportunity in 2 districts, that

"there may well be" a lack of opportunity

4

in 2 other districts, but that blacks in

fact enjoy equal opportunity to partici

pate in the political process in the three

5

remaining districts. Other Solicitors

General might come to still different

conclusions with regard to the political

and racial realities in various portions

of North Carolina.

House District 8 and Senate District 2;

U.S. Brief 21.

House District 36 and Senate District 22;

U.S. Brief 20 n.10 The appendix to the

jurisdictional statement which contains

the District Court's opinion has a

typographical error stating erroneously

that two black citizens have run 'success

fully" Cor the Senate from Mecklenburg

County. The correct word is "unsuccess

fully" . J.S. App. 34a.

House Districts 21, 23 and 39; U.S. Brief

I

6

The government's fact-bound and

statistic-laden brief, noticeably devoid

of any reference to Rule 52, sets out all

of the evidence in this case which

supported the position of the defendants.

It omits, however, any reference to the

substantial evidence which was relied on

by the trial court in finding discrimina

tion in the political processes in each of

6

the seven districts in controversy. The

Senate Report accompanying section 2

listed seven primary factual factors that

should be considered in a section 2 case

and the government does not challenge the

findings in the district court's opinion

that at least six of those factors

supported appellees' claims. On the

contrary, the government candidly acknowl

edges "[t]he district court here faith-

J .A . App. 21a-52a.

7

fully considered these objective factors,

and there is no claim that its findings

with respect to any of them were clearly

erroneous." (U.S. Br. 11).

The government apparently contends

that all the evidence of discrimination

and inequality in the political process

was outweighed, at least as to House

Districts 21, 23 and 39, solely by the

fact that blacks actually won some

elections in those multi-member districts.

It urges

Judged simply on the basis of

'results,' the multimember plans in

these districts have apparently

enhanced — not diluted -- minority

strength. (U.S. Br. 16).

On the government's view, the only

"result" which a court may consider is the

number of blacks who won even the most

recent election. Section 2, however, does

not authorize a court to "judgfe] simply

8

on the basis of [election] 'results'", but

requires a more penetrating inquiry into

all evidence tending to demonstrate the

presence or absence of inequality of

7

opportunity in the political process.

Congress itself expressly emphasized in

section 2 that the rate at which minori

ties had been elected was only "one

circumstance which may be considered."

̂ The district court found, inter alia, that

the use of racial appeals in elections has

been widespread and persists to the

present, J.S. App. 32a; the use of a

majority vote requirement "exists as a

continuing practical impediment to'the

opportunity of black voting minorities" to

elect candidates of their choice, J.S.

App. 30a; a substantial gap between black

and white voter registration caused by

past intentional discrimination; extreme

racial polarization in voting patterns;

and a black electorate more impoverished

and less well educated than the white

electorate and, therefore, less able to

participate effectively in the more

expensive multi-member district elections.

There was also substantial, uncontradicted

evidence that racial appeals were used in

the 1982 Durham County congressional race

and the then nascent 1984 election for

U.S. Senate.

9 *

(Emphasis added). The legislative history

of section 2 repeatedly makes clear that

Congress intended that the courts were not

to attach conclusive significance to the

fact that some minorities had won elec-

8

tions under a challenged plan.

The circumstances of this case illus

trate the wisdom of Congress' decision to

require courts to consider a wide range of

circumstances in assessing whether blacks

are afforded equal opportunity to partici

pate in the political process. A number

S. Rep. 97-417 , 29 n . 1 1 5 ("the election of

a few minority candidates does not

'necessarily foreclose the possibility of

dilution of the black vote', in violation

of this sect ion"), n. 118. ("Thefailure

of plaintiff to establish any particular

factor is not rebuttal evidence of

non-dilution"). See also S. Rep. at 2,

16, 21, 22, 27, 29, 33 and 34-35. The

floor debates are replete with similar

references. In addition, see White v.

Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973) affirming

Graves v. Barnes, 34 3 F. Supp. 7 0 4, T 2 6 ,

732 (W .D . Texas 1972) (dilution present

although record shows repeated election of

minority candidates).

10

of the instances in which blacks had won

elections occurred only after the com

mencement of this litigation, a circum

stance which the trial court believed

9

tainted their significance. In several

other elections the successful black

10

candidates were unopposed. In one example

relied on by the Solicitor in which a

black was elected in 1982, every one of

the 11 black candidates for at-large elec

tions in that county in the previous four

1 1

years had been defeated. In assessing the

political opportunities afforded to black

J .A . App. 37a. See also, S. Rep.at 29

n.115, citing Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485

F .2d 1297, 1307 (5th Cir. 1973),(post-

litigation success is insignificant

because it "might be attributable to

politicalsupport motivated by different

considerations — namely that election of

a black candidate will thwart successful

challenges to electoral schemes on

dilution grounds.")

10 J.S. App. 42a, 44a .

11 J.S. App. 35a, 4 2a-43a.

voters under those at-large systems, the

Solicitor General evidently disagrees with

the comparative weight which the trial

court gave to these election results and

to the countervailing evidence; the

assessment of that evidence, however, was

a matter for the trial court.

The Solicitor General seeks, in the

alternative, to portray his disagreement

with the trial court's factual findings as

involving some dispute of law. This he

does by the simple expedient of accusing

the district court of either dissembling

or not knowing what it was doing. (U.S.

Brief 12) Thus, despite the district

court's repeated statements that section 2

requires only an equal opportunity to

12

participate in the political process, the

Solicitor General insists that "the only

12 J.S. App. 12a, 15a, 29a n.23, 52a.

12

explanation for the district court's

conclusion is that it erroneously equated

the legal standard of Section 2 with one

of guaranteed electoral success in

proportion to the black percentage of the

population." (U.S. Brief 12, emphasis

original). Elsewhere, the Solicitor,

although unable to cite any such holding

by the trial court, asserts that the court

must have been applying an unstated

"proportional representation plus"

standard. (U.S. Brief 18 n.18). The

actual text of the district court opinion

simply does not contain any of the legal

holdings to which the Solicitor indicates

he would object if they were some day

contained in some other decision.

The government does not assert that

the trial court's factual finding of

racially polarized voting was erroneous,

or discuss the extensive evidence on which

1 3

that finding was based. Rather, the

government asserts that the trial court,

although apparently justified in finding

racially polarized voting on the record in

this case, adopted an erroneous "defini

tion" of racial bloc voting. (U.S. Br.

13). Nothing in the trial court's detailed

analysis of racial voting patterns,

however, purports to set any mechanical

standard regarding what degree and

frequency of racial polarization is

necessary to support a section 2 claim.

Nothing in that opinion supports the

government's assertion that the trial

court would have found racial polarization

whenever less that 50% of white voters

voted for a black candidate. In this

case, over the course of some 53 elec

tions, an average of over 81% of white

voters refused to support any black

candidate. (J.S. App. 40a). Prior to this

14

litigation there were almost no elections

in which a black candidate got votes from

as many as one-third of the white voters.

(J.S. App. 41 a-46a) . In the five elec

tions where a black candidate was unop

posed, a majority of whites were so

determined not to support a black that

they voted for no one rather than vote for

the black candidate. (J.S. App.44a).

While the level' of white resistance to

black candidates was in other instances

less extreme, the trial court was cer

tainly justified in concluding that there

was racial polarization, and the Solici

tor General does not assert otherwise.

The Solicitor General urges this

Court to note probable jurisdiction so

that, laying aside the policy of appellate

self-restraint announced in Pullman-

Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1981),

and its progeny, the Court can embark upon

15

its own inquiry into the diverse nuances

of racial politics in Cabarrus, Forsyth,

Wake, Wilson, Edgecombe, Nash, Durham,

and Mecklenburg counties. Twice within

the last month, however, this Court has

emphatically admonished the courts of

appeals against such undertakings.

Anderson v. City of Bessemer City, ___

U.S. ___ (1985); Witt v. Wainwright, ___

U.S. ___ ( 1 985). Twice in the present

term this Court has summarily affirmed

similar fact-bound appeals from district

court decisions rejecting section 2

claims. Starke v, Seamon, No. 83-1823

(October 1, 1984); Brooks v. Allain, No.

83-1865 (Nov. 13, 1984). No different

standard of review should be applied here

merely because in this section 2 case the

prevailing party happened to be the

plaintiffs.

16

Appellees in this case did not seek,

and the trial court did not require, any

guarantee of proportional representation.

Nor did proportional representation result

from that court's order. Prior to this

litigation only 4 of the 170 members of

the North Carolina legislature were black;

today there are still only 16 black

members, less than 10%, a far smaller

proportion than the 22.4% of the popula

tion who are black. Whites, who are 75.8%

of the state population, still hold more

than 90% of the seats in the legislature.

In the past this Court has frequently

deferred to the views of the Attorney

General with regard to the interpretation

of section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. No

such deference is warranted with respect

to section 2. Although the Department of

Justice in 1965 drafted and strongly

jupported enactment of section 5, the

Department in 1981 and 1982 led the

opposition to the amendment of section 2,

acquiescing in the adoption of that

provision only after congressional

approval was unavoidable. The Attorney

General, although directly responsible for

the administration of section 5, has no

similar role in the enforcement of section

2. Where, as where, a voting rights claim

turns primarily on a factual dispute, the

decisions of this Court require that

deference be paid to the judge or judges

who heard the case, not to a justice

Department official, however well inten-

tioned, who may have read some portion of

the record. White v. Regester, 412 U.S.

755, 769 (1973). The views of the

Department are entitled to even less

weight when, as in this case, the Solici

tor's present claim that at-large dis

tricts "enhance" the interests of minority

18

voters in North Carolina represents a

complete reversal of the 1981 position of

the Civil Rights Division that such

districts in North Carolina necessarily

submerge [] cognizable minority population

concentrations into larger white elec

torates." (Section 5 objection letter,

Nov. 30 , 1981 , J - S . App. 6a) .

CONCLUSION

For the above reason, the judgment of

the district court should be summarily

affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

LANI GUINIER*

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

- 19 - <t

LESLIE J. WINNER

Ferguson, Watt, Wallas

and Adkins, P.A.

951 South Independence Blvd.

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Attorneys for Appellees

♦Counsel of Record