St. Regis Paper Company v Roberts Brief for Plaintiffs Appellees

Public Court Documents

April 19, 1979

46 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. St. Regis Paper Company v Roberts Brief for Plaintiffs Appellees, 1979. a5a83786-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/425a4349-1b94-45c1-96af-29600cd8f516/st-regis-paper-company-v-roberts-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellees. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

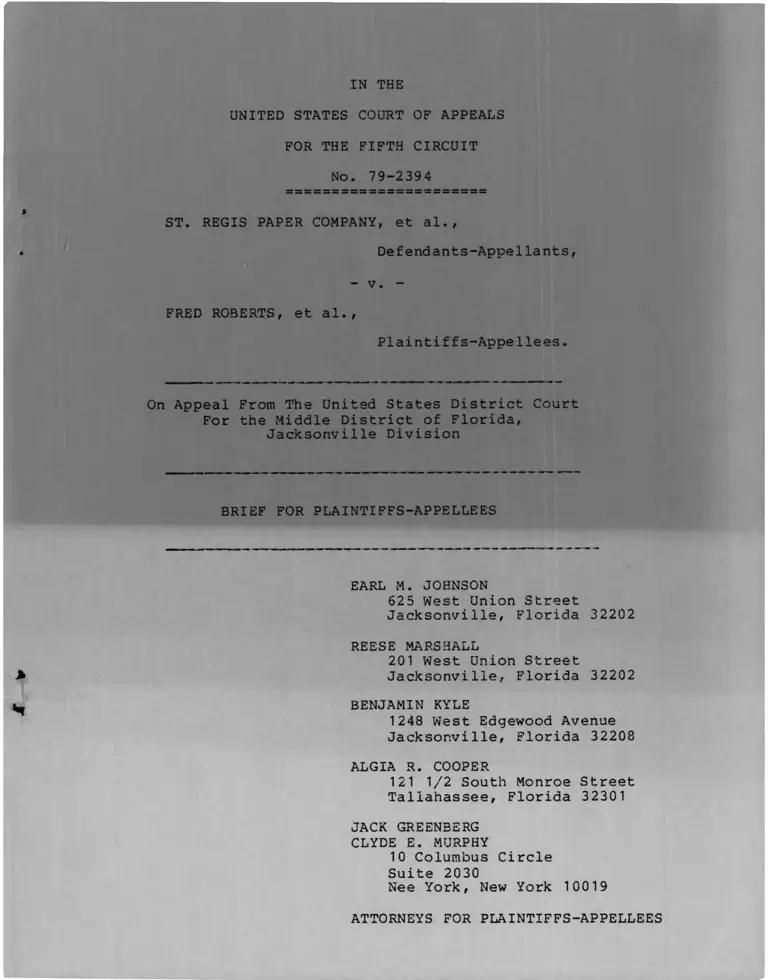

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 79-2394

ST. REGIS PAPER COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants,

- v . -

FRED ROBERTS, et al. ,

Plaintiffs-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For the Middle District of Florida,

Jacksonville Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

EARL M. JOHNSON

625 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32202

REESE MARSHALL

201 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32202

BENJAMIN KYLE

1248 West Edgewood Avenue

Jacksonville, Florida 32208

ALGIA R. COOPER

121 1/2 South Monroe Street

Tallahassee, Florida 32301

JACK GREENBERG

CLYDE E. MURPHY

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

Nee York, New York 10019

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 79-2394

ST. REGIS PAPER COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants-Appe Hants,

- v . -

FRED ROBERTS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees.

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

The undersigned, counsel of record, certifies that the

following listed persons have an interest in the outcome of

this case. These representations are made in order that the

Judges of this Court may evaluate possible disqualification

or recusal.

1. St. Regis Paper Company, a corporation; Interna-

A

tional Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers,

AFL-CIO, and Local Union 1248; International Brotherhood of

Electrical Workers, AFL-CIO, and Local Union 982; United

Paperworkers International Union, AFL-CIO, and Local Union

1 649, Appellants.

2. Fred Roberts, Cuthbert Johnson, John W. Andrews,

Jospeh Butler, James C. Green, Tony Neal, Jr., Lovett Rauler-

son, John W. Clark, Willie Jernigan, individually and on

behalf of all persons similarly situated, Appellees.

Attorneys for Record for Appellees

EARL M. JOHNSON

W. BENJAMIN KYLE

REESE MARSHALL

ALGIA R. COOPER

JACK GREENBERG

CLYDE E. MURPHY

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 79-2394

ST. REGIS PAPER COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants

v

FRED ROBERTS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY LOCAL RULE 13(j ) (2)

Counsel for appellants believe that if the Court deems

it necessary to probe the issues regarding the impact of

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 (1977) on a previously entered consent decree

then oral argument may be useful.

»

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Statement of Issues .................................. 1

Statement of the C a s e ................................ 2

Summary of Argument ................................ 10

ARGUMENT

THE DISTRICT COURT CORRECTLY HELD THAT

THE COURT HAD JURISDICTION TO CONSIDER

VIOLATIONS OF THE CONSENT DECREE ............... 12

A. The Court Has The Power To Enforce

Its Own Orders Whether Entered By

Consent Or After Active Litigation . . 12

B. Section XVI Does Not Strip The

Court of Jurisdiction To Enforce

The Consent Decree, But Simply

Limits The Ability Of The Parties

To Petition The Court For "Other

and Further Relief." ................. 13

C. Even If Section XVI Were Intended

To Strip The Court Of Jurisdiction

To Enforce The Decree The District

Court's January 30, 1978 Order

Entered Nunc Pro Tunc December 31,

1976 Extended The Court's Juris

diction Pendente Lite Of The Contempt

Proceedings............................. 2 3

D. The Supreme Court Decision In

Teamsters Does Not Compel Any

Alteration Of The Seniority Provi

sions Of The Consent D e c r e e ........... 25

Conclusion 36

11

Table of Cases

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) . . 4

Bing v. Roadway Express, Inc., 485 F.2d 441 (5th

Cir. 1 9 7 3 ) ......................................... 34

Boles v. Union Camp. 5 FEP Cases 529 (S.D. Ga.

1972) 4,31

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metal Co., 421 F.2d 888,

(5th Cir. 1970) 30

Dawson v. Pastrick, 600 F.2d 70 (7th Cir. 1979) . . 11,27,30

Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co., 406

F . 2d 399 (5th Cir. 1 9 6 9 ) ......................... 30

Eaton v. Courtaulds of North America, Inc.,

578 F. 2d 87 (5th Cir. 1978)..................... 17,18,22

EEOC v. Longshoremen (ILA), Local 829 and 859,

9 EPD 1(10,159 (D. Md. 1975) 12

EEOC v. Plumbers & Pipefitters Local 189, 438

F . 2d 408 (6th Cir. 1971) ....................... 12

EEOC v. Safeway Stores, Inc. F.2d , 21 EPD

1(30,456 (10th Cir. 1979) 11,30

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 474

(1976)......................................... 13,14,26,34

Gamble v. Birmingham Southern R.R. Co., 514 F.2d

678 (5th Cir. 1975) ............................. 34

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v.

United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) . . . . 11,25,26,27,29,32

James v. Stockham Valves & Fittings Co.,

559 F . 2d 310 *5th Cir. 1 9 7 7 ) ............... 22,26,32,34,35

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491

F . 2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974) 16

King Seely Thermo Company v. Alladdin

Industries, Inc., 418 F.2d 31 (2nd Cir.

(1969)............................................. 10

Local 189, United Papermakers & Paperworkers

v. United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir.

1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970)- • • 4,14,15,16,17,31

Page

1 X 1

Long v. Georgia Kraft Co., 490 F.2d 557 (5th Cir.

1 9 7 1 ) 31

Miller v. Continental Can Co., 12 EPD 1111, 191

(S.D. 1 9 7 6 ) ....................................... 4,31

Myers v. Gilman Paper Corp., 544 F.2d 837 (5th

Cir. 1977), reversed and vacated in part,

556 F . 2d 758 (5th Cir. 1977) ............... 11,14,29,31,33

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach, 398 F.2d 496

(5th Cir, 1 9 6 8 ) ................................ 30

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494

F . 2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974) 14

Rogers v. International Paper, 510 F.2d 1340

(8th Cir. 1975) , vac1d and rem'd 423 U.S

809 (1975), new trial directed 526 F.2d

722 (8th Cir. 1975) 31

Sarabia v. Toledo Police Patrolman's Ass., 601

F . 2d 914 (6th Cir. 1979)........................ 14,28

Southbridge Plastics Division v. Local 759,

Rubber Workers, 565 F.2d 913 (5th Cir. 1978). . 11,29

Stevenson v. International Paper Co., 516 F.2d

103, 111-118 (5th Cir. 1975)................... 4,15,20,31

System Federation No. 91 v. Wright, 364 U.S.

642 (1961) 28,24

Theriault v. Smith, 523 F.2d 601 (1st Cir. 1975) . 28,29

United States v. Allegheny Ludlum Industries,

517 F.2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975), cert denied,

423 U.S. 1056 (1976) 30

United States v. Armour & Co., 402 U.S. 673 (1971) 15,16,17

United States v. Hall, 472 F.2d 261 (5th Cir.

1972) 10,12,13

United States v. ITT Continental Baking Co.,

420 U.S. 223 (197 ) ............................ 16,17

United States v. Swift and Company, 286 U.S.

106 (1923) 10,12,16,17

United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp.,

391 U.S. 244 (1968) 13

Page

XV

Page

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F.2d 1159

(5th Cir. 1976) ..................... 15,16,31,34,35

Statutes

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seg................... Passim

42 U.S.C. § 1 9 8 1 .............................. Passim

Other Authorities

H. R. Northrup, (L. Rowan, D. T. Barnum and

J. G. Howard, Negro Employment in Southern

Industry, Volume IV, Part 1, at 51 (1979). . . 31,32

Note On Abbreviations

R............................... Record

R.E............................. Record Excerpts

Transcript..................... Transcript of Hearing on

Issue of Court's Jurisdiction

before Honorable Charles R.

Scott, April 4, 1979

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 79-2394

ST. REGIS PAPER COMPANY, et al.,

Defend an ts-Appe Hants,

- v . -

FRED ROBERTS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For the Middle District of Florida,

Jacksonville Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

STATEMENT OF ISSUES

1. Whether the Court has jurisdiction to consider

violations of a previously entered consent decree.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On May 11, 1969, plaintiffs filed suit against the

defendant St. Regis Paper Company (hereinafter the "Company")

and the International Association & Machinists and Aerospace

Workers, AFL-CIO and its Local No. 1248; the International

Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, AFL-CIO and its Local No.

982; the International Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite and

Paper Mill Workers, AFL-CIO and its Local No. 749; the United

Papermakers and Paperworkers, AFL-CIO and its Local No. 636

(hereinafter referred to as the "unions"), alleging inten

tionally discriminatory employment practices in violation of

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000e

et seq., and 42 U.S.C. §1981.

Specifically plaintiffs alleged that the defendants

had restrictively hired members of the affected class on the

grounds of race and initially assigned them only to certain

designated jobs without regard to their qualifications and on

a different basis than they hired, promoted, transferred or

assigned similarly situated white persons. Similarly plain

tiffs alleged that the defendants perpetuated the initial

racial assignments of members of the affected class by

entering into, implementing and maintaining a system of job

and departmental seniority provisions in the respective

collective bargaining agreements which granted preferential

terms, conditions and privileges of employment to white

employees.

2

The initial proceedings conducted in this action estab

lish without contradiction that the Union defendants estab

lished and maintained jurisdiction units, the effect of

which was to perpetuate the effects of the racially motivated

hiring practices of the Company. For example, prior to

December 24, 1968, and pursuant to collective bargaining

agreements between the Company and Pulp and Sulphite and its

Locals 749 and 757 certain jobs or classifications were

represented by Local 749 and certain jobs or classifications

were represented by Local 757. Local 757's membership was

composed of black employees and no white employee worked in

any job or classification represented by Local 757.

Prior to November 18, 1963, Local 749's membership was com

posed of white employees and no black employee worked in a

job or classification represented by Local 749. Similarly,

pursuant to collective bargaining agreements between the

Company and Machinists and its Local 1248, Electrical Workers

and its Local 982 and Paper Makers and its Local 636, certain

jobs or classifications are represented by Locals 1248, 983

and 636. Prior to September 9, 1968, the membership of

Local 1248 was composed of white employees and no black

employee had worked in a job or classification represented by

Local 1248. Prior to May 19, 1969, Local 982's membership

was composed of white employees and no black employee had

worked in a job or classification represented by Local 982.

Prior to September 12, 1966, Local 636's membership was

3

composed of white employees and no black employee had worked

in a job or classification represented by Local 636.

Moreover, even after all of the defendants except

defendants IBEW, and its Local 982, entered into an agreement

under which certain lines of progression were nominally

consolidated or merged, the defendants failed to restructure

the lines of progression in such a way as to eliminate the

prior discrimination, or to allow black employees to transfer

between lines of progression without loss to their ac

cumulated seniority.

Following extensive discovery the parties negotiated a

settlement which the district court approved on January 28,

1972. The consent decree extended to members of the affected

class various relief typical of that obtained via settlementV

and/or litigation involving the southern paper industry.

This relief included application of a system of mill senior

ity, in place of the job or departmental seniority system

whenever employment decisions affecting the status of affected

class members who were specifically identifiable victims of

disparate treatment were made; the elimination of the require-

V Stevenson v. International Paper Co., 516 F.2d 103, 111-

118 (5th Cir. 1975); Local 189, United Papermakers & Paper-

workers v. United States, 416 F .2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969)

cert, denied^ 3^t U.S. 919 (1970); see also, Albemarle

Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975); Boles v. Union

Camp, 5 FEP Cases 529 (S.D. Ga. 1972); Miller v. Con

tinental Can Co., 12 E.P.D. 1[11,191 (S.D. Ga. 1976).

4

ment that job applicants possess a high school diploma or

achieve satisfactory scores on nonvalidated personnel or

aptitude tests; wage rate retension or "red circling" for

members of the affected class transferring to more desirable

lines of progression; advanced level entry and job skipping,

as well as other provisions relating to hiring and assignment,

recruiting, training, back pay, election of union officers

and periodic reports to the court and to the attorneys for

plaintiffs. The decree also provided at section XVI.

Jurisdiction in this action for such other

and further relief as may be appropriate con

sistent with this Order is hereby retained

until January 1, 1977 unless sooner modified,

dissolved or extended. R.E. 59a.

On December 30, 1976, plaintiffs filed motions for

contempt, for further relief, modification and extension of

the consent decree, and for extension of jurisidction pendente

lite and hearing. R.E. 79a. Plaintiffs alleged that the

defendants had consistently violated the terms and frustrated

the purpose of the decree by unilaterally altering the lines

of progression, and refusing to allow members of the affected

class to use mill seniority to transfer into craft positions

in the same manner as their white co-workers had historically

been allowed to do. Specifically plaintiffs asserted that

the defendants were violating various sections of the consent

decree including "section II-A (sic) of the consent decree by

refusing to 'utilize permanently in place of job or department

5

as well asal seniority a system of mill seniority...";

violations of various other sections including sections V

(Qualifications) VIII-A, VIII-B (Training) and X (union member

ship) of the decree. As relief the plaintiffs sought a

modification of the decree so as to require the defendants to

establish non-discriminatory objective job-related qualifi

cations for craft positions; the immediate promotion or

transfer of qualified affected class members to craft posi

tions; as well as other modifications consistent with the

original purpose of the consent decree as filed. In essence,

then, plaintiffs' charged specific violations of the consent

decree by the defendants and sought as a remedy relief in

addition to that already provided for in the decree in order

to resolve the inequities brought about by the defendants'

noncompliance with the terms of the consent decree.

On July 11, 1977 plaintiffs' motion was referred to the

Honorable Harvey E. Schlesinger, United States Magistrate, to

make findings and a recommendation. On December 14, 1977,

defendants filed a motion to dismiss plaintiffs' contempt

motion arguing that the Court's jurisdiction had lapsed;

that plaintiffs were subject to laches in filing the motion;

2/

2/ The section while incorrectly identified in plaintiffs'

motion clearly referred to and was understood by the defen

dants to mean section II-B:" The defendants are ordered to

utilize permanently in place of job or departmental senior

ity a system of mill seniority with respect to temporary

and permanent job assignments, including promotions,

demotions and selections for training of affected class

employees..."

6

and that plaintiffs were attempting to unilaterally modify

the consent decree.

On January 30, 1978, the District Court rejected the

defendants' contentions and entered an order nunc pro tunc

December 31, 1976, extending the Court's jurisdiction over

the consent decree pendente lite of the contempt proceedings.

There, the court stated the issues as follows:

...[W]hether the court's jurisdiction expired

on January 1, 1977, so that the mere filing

of a contempt petition was insufficient to

extend or invoke the court's jurisdiction

or whether the court's inherent equity juris

diction to enforce its orders was timely

invoked by the petition for contempt

proceedings and the motion to extend the

court's order. R.E. 41a-42a.

The court not only held that plaintffs' petition for

contempt and further relief was timely filed but went on to

hold:

Whether an order of the court is consensual

or adversary, it is an adjudication and it

carries the force and effect of law. When

parties agree to a consent order, they

recognize that they are together submitting

themselves to the court's jurisdiction; and once

the order is issued, it is, like any other order

of the Court, to be complied with and faith

fully obeyed. If it is not then like any other

order of the Court, the Court retains inherent

jurisdiction to see that its orders are obeyed.

R.E. 43a.

Following the entry of the January 30, 1978 order, the

parties alternately engaged in extensive proceedings aimed

at completing discovery in anticipation of trial, and,

settlement negotiations which might resolve the matter.

7

Finally on February 28, 1979, plaintiffs filed a motion

for preliminary injunction and a motion for partial summary

judgment for noncompliance by the defendants with a specific

section of the 1972 consent decree. Specifically, plaintiffs

sought to obtain preliminary relief and summary judgment on

the question of whether the consent decree entered by the

court on January 22, 1972 required the defendants to per

manently utilize a system of mill seniority with respect

to affected class employees in place of the job or depart-

3/

mental seniority system which preceded the consent decree.

The essential difference in the subject matter of the

two motions is that the December, 1976 motion for contempt

and further relief, while it alleged violations of the

consent decree, sought to obtain relief not provided for in

the decree and to exend the time period during which such

further relief would be obtainable. On the other hand,

the February, 1979 motion raised a single discrete issue, to

wit: the failure of defendants to "permanently" utilize a

system of mill seniority with respect to employment decisions

affecting members of the affected class, as explicitly requir

ed by section II.B. of the decree:

3/ Despite the district court's January 30, 1978 determina

tion to consider plaintiffs' claims, the company proceeded

to implement its interpretation of the decree when on or

about February 22, 1979, company officials began informing

members of the affected class that as of March 2, 1979 they

would no longer be able to use mill seniority to prevent

layoff or for other employment decisions.

8

II.

B. The defendants are ordered to utilize per

manently in place of job or departmental

seniority a system of mill seniority with

respect to temporary and permanent job

assignments including promotions, demotions

and selection for training of affected

class employees as follows:

(1) Total mill seniority (i.e. , the length

of continuous service in the mill)

alone shall determine who the "senior"

bidder or employee is for purposes

of all temporary or permanent pro

motions, temporary or permanent

demotions, including layoffs and

recalls, and for training, whenever

one or more of the competing em

ployees is an affected class employee,...

R.E. 49a-50a.

Thus, while the permanence of the seniority provision of the

decree is an issue in both motions, the December 1976 motion

sought to modify the consent decree, whereas, the February,

1979 motions merely sought to enforce it.

On April 19, 1979 the District Court, pursuant to

plaintiffs' February 28, 1979 motions, issued an order

upholding the court's jurisdiction to consider violations of

the consent decree and referred plaintiffs' motions for

summary judgment and preliminary injunction to Magistrate

Schlesinger. The court noted with respect to the seniority

provision, that "Nowhere is this provision or any other

expressly limited to any term or period of time." R.E. 37a.

Rejecting the defendants' assertions regarding the jurisdic

tion clause the court held:

- 9 -

The jurisdictional clause speaks to the Court's

jurisdiction to award "such other and further

relief as may be consistent with this order."

Thus, the phrase "unless sooner modified dis

solved, or extended" relates to the Courts'

jurisdiction to alter the relief provided by

the decree; not to the period of time the

decree is to have effect. In other words, the

court retained jurisdiction to grant additional

relief,not embodied in the decree, for a period

of five years. The jurisdictional clause how

ever, in no way, effects or limits the period

of time in which the duties and obligations

expressed in the decree are to be carried out

and fulfilled. R.E. 37a.

Therefore the District Court held: "The Court has jurisdic

tion to consider alleged violations of the consent decree

entered on January 28, 1972" R.E. 39a.

On May 10, 1979 the defendants filed a notice of appeal

and on August 22, 1979 the record on appeal was filed.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The power of a court to enforce the terms of an injunc

tion are unassailable. This is clearly the case even though

the injunction was entered by consent and whether or not

the power to enforce or modify was reserved by its terms.

United States v. Swift and Company, 286 U.S 106 (1932).

The district court's holding corectly exercises the court's

authority to insure that its orders are obeyed. United

States v. Hall, 472 F .2d 261 (5th Cir. 1972); King Seely

Thermos Company v. Alladdin Industries, Inc., 418 F .2d

31 (2nd Cir. 1969).

Section II.B of the consent decree plainly unequivocally

and permanently enjoins the defendants from the continued use

10

of a job or departmental seniority system whenever the

rights of affected class members are involved. It follows

that the defendants unilateral attempt to violate this

provision is properly the subject of inquiry by the court in

an effort to protect the integrity of its orders.

The Supreme Court decision in International Brother

hood of Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977)

does not compel any alteration or curtailment of the

bargained-for seniority relief obtained in the consent

decree. To the contrary, both the history of discrimina

tion in the southern paper industry as well as the well

settled principle that the law generally encourages

settlements argues against upsetting the reasonable

settlement reached in this case. Dawson v. Pastrick,

600 F .2d 70, 75-76 (7th Cir. 1979); EEOC v. Safeway

Stores, Inc., ___ F.2d ___ 21 EPD 1|30,456 ( 1 0th Cir.

1979).

The district court's opinion in this case provides

a carefully considered assertion of the court's author

ity, and a well reasoned interpretation of the various

provisions of the consent decree. Morever, contrary to

the situations posed by Myers v. Gilman, 544 F .2d 837,

on hearing, 556 F .2d 758 (5th Cir. 1977) and Southbridge

Plastics Division v. Local 759, Rubber Workers, 565

F.2d 913 (5th Cir. 1978) both the consent decree and

the district court's interpretation of the decree care-

- 11 -

fully harmonize the policies of Title VII and the

National Labor Relations Act.

ARGUMENT

THE DISTRICT COURT CORRECTLY HELD THAT THE

COURT HAS JURISDICTION TO CONSIDER VIOLATIONS

OF THE CONSENT DECREE

A. The Court Has The Power To Enforce Its Own

Orders Whether Entered By Consent Or After

Active Litigation

A court of equity may modify a decree of injunction

even though it was entered by consent and whether or not the

power to modify was reserved by its terms. United States v .

Swift and Company, 286 U.S 106 (1932). This expression of

the inherent authority of a court to enforce its own decrees

is frequently noted throughout the case law, in civil rights

cases generally, United States v. Hall, 472 F .2d 261 (5th

Cir. 1972), and in cases involving the enforcement of consent

decrees under Title VII, EEOC v. Longshoremen (ILA),

Local 829 and 859, 9 EPD 1(10,159 (D. Md. 1 975). In EEOC

v. Plumbers & Pipefitters, Local 189, 438 F .2d 408, 414

(6th Cir. 1971), for example, the court, after recognizing

that 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(i) conveyed to the EEOC the author

ity to commence procedings to compel compliance with the

district court's order, went on to assert:

And beyond question, the District Court had

authority either sua sponte or on petition

to reshape its injunction so as to achieve

"its original and wholly appropriate purpose.

United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp.,

H5T U.S. 244 (1^68); King-Seely Thermos Co~.

v. Aladdin Industries, Inc., 418 F .2d 31

(2nd Cir. 1969).

12

It follows that a court's power to reshape or modify

a previously entered consent decree or other order,

United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp., 391 U.S 244

(1968), necessarily encompasses the inherent power to protect,

enforce and effectuate that decree when its provisions

have been violated. As the Fifth Circuit has noted:

...broad applications of the power to punish

for contempt may be necessary, as here, if courts

are to protect their ability to design appro

priate remedies and make their remedial orders

effective.

U.S. v. Hall, supra 472 F .2d at 266.

In the case at bar the consent decree expressly calls

for the permanent imposition of some forms of relief, and

the gradual phasing out of other forms. For example, the

provision with respect to mill seniority is clear and

unambiguous in its statement of duration:

The defendants are ordered to utilize

permanently in place of job or departmental

seniority a system of mill seniority with

respect to temporary and permanent job assign

ments, including promotions,~demotions and

selection for training of affected class

employees... R.E. 49a. 4/

Moreover, the use of mill seniority and seniority carryover

under the "rightful place" doctrine is designed to give

victims of discrimination the incentive to transfer by remov-

4/ The mill seniority relief obtained by the affected

class is fully consistent with the aims of Title VII and has

been regularly approved and/or employed by the Supreme

Court as well as this Circuit. Franks v. Bowman Trans-

13

ing a major disincentive to such transfer, i.e., the loss of

accumulated seniority. Thus a provision allowing a

discriminatee to use his accumulated mill seniority enables the

discriminatee to obtain sufficient seniority in a new unit to

permit him or her to effectively compete for advancement and

provides protection against the threat of layoff to which the

discriminatee would otherwise be exposed because of prior

5/

discrimination.

It follows that a time limitation such as five years

would emasculate the remedy, as it would remove the protec

tion of members of the affected class against demotion or

dismissal where they sought the more desirable positions

in other bargaining units. Moreover there is no support in

1/

portation Co., 424 U.S. 474 (1976); Local 189, United Paper-

makers and Paperworkers v. United States, 189, 416 F .2d 980

(5th Cir. 1969) reh'g denied per curiam 416 F .2d 980 (5th

Cir. 1969) cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970); Pettway v .

American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F .2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974);

Myers v. Gilman, supra; Sarabia v Toledo Police Patrolman's

Assn., 601 F .2d 914 (6th Cir. 1979).

5/ In the case at bar one member of the affected class

used his mill seniority to obtain a promotion and transfer

into the maintenance department as a carpenter earning

$9.60 per hour. However as a result of the defendants'

unilateral action in terminating the use of mill seniority

by members of the affected class, this class member was

unable to use mill seniority when the department was faced

with company imposed layoffs. In addition because of

the provisions of the collective bargaining agreement the

affected class member was prevented from going back to his

old job. Consequently, the affected class member was forced

to accept an entry level position.

14

the case law for the proposition that the use of mill seniority

should be so limited.6/

The defendants have argued here and in the court below

that the "four-corners" doctrine, see United States v.

Armour & Co., 402 U.S 673 (1971), is determinative for any

interpretation of the consent decree. However, rather than

apply this doctrine correctly, the defendants seek to distort

its meaning so that (1) the decree is not read with

any internal consistency; and (2) the decree is removed from

the context of the remedies.

6/ The defendants cite this Court's opinion in Stevenson

v. International Paper Co., 516 F .2d 103, 113, 118 (5th Cir.

1975) for the proposition that the relief obtained in a

decree under Title VII is properly limited in duration.

However the defendants omit to mention three salient points;

(1) the overall duration of a consent decree or order was

not at issue in Stevenson, supra, but rather the adequacy of

relief previously obtained; (2) the quoted section of the

opinion, Id. at 113, deals specifically with "Red Circling", a

form of reTief which in the present case is explicitly limited

in Section VI of the decree so that it either expires after

one usage; expires if the affected class member is permanently

assigned to a higher paying job; or expires if he waives

promotion four times; and (3) while the court explicitly

points out that the employer has a legitimate interest in

limiting such relief it goes on to indicate that these

limitations "... cannot be considered in a vacuum ... but

must be viewed in light of the entire remedy offered. See

also Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F.2d 1159 (5th Cir.

1976) , wherein the Court observed, "The rule, adopted by

this Court in Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers

v. U.S., ... and recently endorsed by the Supreme Court in

Franks v. Bowman, ... is that blacks discriminated against

must be given such remedial relief as to enable them to

achieve their "rightful place" in an employer's employment

hierarchy".

15

In United States v. ITT Continental Baking Co., 420 U.S

223, 238 ( 1975) the Supreme Court, interpreting its decision

in Armour, supra, held:

Since a consent decree or order is to be con

strued for enforcement purposes basically as a

contract, reliance on certain aids to construc

tion is proper as with any other contract. Such

aids include the circumstances surrounding the

formulation of the consent order, any technical

meaning words used may have had to the parties,

and any other documents expressly incorporated

in the decree. Such reliance does not in any

way depart from the four-corners' rule of

Armour. 7/

Here the district court properly considered the situa

tion which rise to the decree in the first instance. Focus

ing particularly on the bargained-for relief obtained by both

parties, the Court expressed an acute awareness of the

appropriate breadth of that relief. In addition, the court's

interpretation exhibits its consideration of the underlying

legal context for the type of relief embodied in the decree.

Thus, properly considering the concepts of "mill seniority"

and "rightful place" the court made its interpretation of the

decree within the context of opinions of this Court such

as Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers v. United

States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969); Watkins v. Scott Paper

Co., supra; and Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491

7/ Similarly, the defendants' assertion that a court may

not modify a consent decree, as such a decree is to be viewed

as a contract and not a judicial act (see Joint Brief of All

Appellants p. 14) is wholly without merit and was specific

ally rejected by the Supreme Court in United States v .

Swift Co., supra.

16

F.2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974), which make plain the purposes and

extent of relief in Title VII cases.

Similarly the court below was required to interpret the

consent decree in light of prevailing law in the Circuit at

the time the decree was entered. As such Local 189, would

certainly have provided the most appropriate legal context

for understanding the breadth and purpose of the provisions

of the decree. Also, at the time the decree was entered the

district court was required to make a finding that the relief

provided therein was fair, adequate and reasonable. Certainly

that determination would also have been made pursuant to the

Court's admonition in Local 189, that "... blacks previously

discriminated against must be given remedial relief as to

enable them to achieve their rightful place."

In Eaton v. Courtaulds of North America, Inc., 578 F . 2d

87 (5th Cir. 1978) this Court carefully considered the

Supreme Court's holdings in United States v. Armour Co.,

supra, 402 U.S at 681-82 and United States v. ITT Continental

Baking Co., supra, 420 U.S at 238 and held that while "if

possible" courts are required to anlayze an agreement without

resort to extrinsic considerations:

Where amgibuities exist in the language of a

consent decree, the court may turn to other

'aids to construction,' such as other

documents to which the consent decree refers,

as well as legal materials setting the con

text for the use of particular terms.

17

Eaton v. Courtaulds of North America, Inc., surpa 578

F.2d at 91.

As was the case in Eaton, supra, the district

court was required to construe section XVI of the decree in

the light of other portions of the agreement whose language

specifically referred to terms. It follows that the

interpretation offered by the district court is the "natural

and approriate reading" since it reinforces the internal

consistency of the decree and recognizes the logical context

in which the relief is provided.

B. Section XVI Does Not Strip the Court of

Jurisdiction To Enforce The Consent Decree,

But Simply Limits The Ability Of the

Parties To Petition The Court For "Other

And Further Relief"

In both the court below and in this Court, the defen-

dants-appellants have offered a strained interpretation of

section XVI. While assuming the stance of one who wants only

the "plain meaning" of the decree to be enforced, they have

ignored the operative language of section XVI. While arguing

that the four corners' doctrine prohibits plaintiffs or the

Court from considering Section XVI in light of the other

sections of the decree, from considering the underlying legal

basis for the relief obtained by plaintiffs, or from consider

ing the effects of the withdrawal of such relief, they nonethe

less seek to present bogus precedent for a limitation on that

relief and to indicate that the relief is now unnecessary.

18

Section XVI states:

Jurisdiction in this action for such other

and further relief as may be appropriate con

sistent with this Order is hereby retained until

January 1, 1977, unless sooner modfied, dissolved

or extended, (emphasis added). R. E. 591.

As the district court below held, this clause,

...speaks to the Court's jurisdiction to award 'such

other and further relief as may be consistent with

this order." Thus, the phrase 'unless sooner

modified, dissolved, or extended' relates to the

Court's jurisdiction to alter the relief provided

by the decree; not to the period of time the

decree is to have effect. R.E. 37a.

The defendants would have this Court read the phrase

"for such other and further relief" completely out of the

decree, and pretend that section XVI instead robs the

Court of jurisdiction to enforce the permanent injunctive

portions of the decree. However, as Judge Scott indicated

£/

below it simply "doesn't say that." Moreover, there is

no reason for the section to be given so broad an interpre

tation, as each section indicates its life.

For example, section II states that "the defendants

are ordered to utilize permanently ... a system of mill

seniority...", while section IV indicates that "the company

shall not require as a prerequisite for hiring that appli

cants possess a high school diploma or its equivalent" or

8/ Transcript p. 60.

19

pass a non-validated personnel or aptitude test.

Section VI indicates that an affected class member may

use his "red circle" wage protection unless or until "(i)

he is permanently assigned to a position paying a higher

rate, or (ii) he waives promotion after entry of his Order

four times," moreover the decree limits the red circle

protection to one voluntary transfer for each member of the

affected class. Other sections of the decree

involving Recruiting (§VII), Training (§VIII) and Union

Membership (X), only require that the company recruit, and

train and that the union admit members on a nondiscrimina-

tory basis. While these sections do not express any time

limitation, their terms are merely consistent with the

requirements of Title VII, §1981 and the U.S. Constitution

and do not impose any onerous condidions that might be said

to be "extraordinary" or antagonistic to the employer's

"interest in reestablishing stability to his work environ

ment." Stevenson v. International Paper Co., supra. In fact,

in lieu of a time limitation section VII F states:

It is the purpose of this section to permit

flexibilty in the Company's efforts to notify

the black community of job opportunities. This

provision is not intended to require the Company

to use newspaper or other media advertising unless

such advertising is necessary to accomplish the

objective of giving broad notice to the black

community of job opportunities.

As the district court indicated, reading the decree as

a whole, particularly in light of the explicit language of

sections XVI and II.B:

20

...the Court retained jurisdiction to grant

additional relief, not embodied in the decree,

for a period of five years. The jurisdictional

clause, however, in no way, effects or limits

the period of time in which the duties and

obligations expressed in the decree are to be

carried out and fulfilled. To read Clause XVI

any other way would be to disregard the plain

language of the section. R.E. 37a.

It is contrary to logic to argue as do the defendants

that the term "permanent" in section II.B means permanent

2/

for five years. Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary, G &

C. Merriam Co., 1977 defines "permanent" as "continuing or

enduring without fundamental or marked change: stable." It

is simply not supportable to suggest that the parties could

have had any other definition in mind for using the word

permanent in section II.B. of the decree. In addition, while

castigating the Court below for considering the legal

context for relief such as mill seniority, the defendants

12/argued below as they do here that there are adequate

legal reasons for limiting the mill seniority relief. In so

doing they grossly misstate the relation of the "rightful

place" theory to the relief obtained in the decree and then

go on to erroneously suggest (1) that the members of the

affected class have reached their rightful place and (2)

that therefore the mill seniority relief is no longer

necessary.

In the first instance the "rightful place" theory is

relevant in that it provides the legal context for the use

9/ Joint Brief of All Appellants at p.13.

10/ Transcript p. 62.

21

mill seniority, discriminatees would have no incentive to11/transfer for fear of committing "seniority suicide" in

the event of layoffs. Thus, the defendants' notion that once

a member of the affected class has used his mill seniority

and/or red circle protection to transfer or promote he has

reached his rightful place, is not only absurd it also fails

to adequately consider the fact that without the continued

use of mill seniority the affected class member cannot hope

to maintain his position. For example in the case at bar one

affected class member was demoted to entry level status for

exactly this reason.

The defendants' view presupposes that in every case

where an affected class member has transferred to a new

department or new line of progression, from which blacks were

previously excluded, that he now has sufficient job or

department seniority to protect his new position. Moreover,

while the defendants proudly extoll the fact that several

affected class members have been promoted under the terms of

the consent decree they fail to indicate that only a handful

have reached the most desirable assignments to the maintenance

of the term mill seniority in the decree. See Eaton v.

Courtlauds of North America, Inc., supra. Absent

11/ James v. Stockham Valves & Fittings Co., 559 F .2d 310

(5th Cir. 1977).

22

department. And, significantly, it is these men who

face the most severe threat in that the loss of their mill

seniority may mean unemployment.

C. Even If Section XVI Were Intended To Strip The

Court Of Jurisidction To Enforce The Decree -

The District Court's January 30, 1978 Order

Entered Nunc Pro Tunc December 31, 1976

Extended The Court's Jurisdiction Pendente Lite

Of The Contempt Proceedings

On January 30, 1978 the District Court entered an Order

denying the defendants' motion to dimiss the contempt

proceedings and furher ordering:

Plaintiffs' motion for extension of jurisdiction

over the consent decree pendente lite of the

contempt proceeding, is granted nunc pro tunc

December 31, 1976. R.E. 43a.

There, notwithstanding the defendants' arguments to the

contrary, the district court held that the motions for

contempt and further relief were timely filed and that "the

Court retains inherent jurisdiction to see that its orders

are obeyed." R.E. 43a.

The issues underlying the present appeal, i.e., the

breadth of section II.B. and section XVI were likewise

expressly raised by plaintffs' motion for contempt and

futher relief. That is, while the threatened March 2, 1979

layoff of affected class members prompted plaintiffs'

12/

1_2/ See Plaintiffs' Motion for Contempt for Further Relief

... It can hardly seem accidental that the principle

effect of defendants' reading of section II.B, the elimina

tion of Blacks from the maintenance department was also an

underlying cause of the December 30, 1976 motion.

23

motions for summary judgment and preliminary injunction,

the expressed purpose of those motions was to obtain an

order (1) indicating "the continuing obligation of the

defendants to abide by the provisions of the Consent Decree

mandating the permanent use of mill seniority when membersIV

of the affected class compete for employment positions"

and (2) ordering the defendants "to utilize a system of mill

seniority for purposes of all temporary and permanent job

assignment, including promotions, demotions,layoffs, recalls,

and selection for training of affected class emolyees as11/provided in Section II.B of the Consent Decree..."

Thus the issue raised by plaintiffs' present motion

could have been heard under the grant of jurisdiction in the

court's January 30, 1978 Order as the mill seniority issue

was expressly raised in plaintiffs' motion for contempt which

the court held was timely filed.

Plaintiffs' Motion For Contempt... explicitly alleged:

b) The Company has violated section II-A (sic)

of the consent decree by refusing to "utilize

permanently in place of job or departmental

seniority a system of mill seniority with

respect to temporary and permanent job assign

ments, including promotions, demotions and

selections for training of affected class

employees... R.E. 80a.

13/ See Plaintiffs Motion for Partial Summary Judgment.

£7 2229.

14/ See proposed Order Sustaining Plaintffs' Motion for

Preliminary Injunction. R. 2225.

24

Moreover the company's response to plaintiffs' motion

interposed essentially the same defense, i,e., that section

XVI terminates all the relief of the decree, as they put

1 5/

forth in their brief.

It follows that no new issue was raised by plaintiffs

February 28, 1979 motions. Rather, following the breakdown

of settlement discussions, and the apparently imminent layoff

of many of the most industrious members of the affected

class, plaintiffs sought an immediate determination of the

one issue included in the motion for contempt which would

sustain the gains made by the affected class members and

prevent the unilateral abrogation of the consent decree by

the defendants.

D. The Supreme Court Decision In Teamsters Does

Not Compel Any Alteration of the Seniority

Provisions of The Consent Decree

In International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977 ("Teamsters") a suit brought

by the Government under Title VII, the Supreme Court held

that Section 703(h) accorded a narrow immunity to a bona fide

seniority system even though that system perpetuated pre-Act

discrimination. The Court held that where conduct prohibited

by Title VII has not entered into the establishment, negotia-

15/ See, defendant company's Answer to Motion For Contempt

and Other Relief: Counter-Motion to Declare Consent Order

dated January 28, 1972, dissolved and terminated, and

Motion to Dismiss Motion for Contempt.

25

tion of maintenance of a seniority system, such system is

immune under §703(h) of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964. However, where a discriminatory purpose did enter into

the establishment, negotiation or maintenance of a seniority

system, it is not shielded by the limited immunity granted by

§703(h).

Nowhere does Teamsters hold, as the defendants suggest,

that the permanent implementation of mill seniority rather

than job or departmental seniority is "contrary to current

± 6/

law under Title VII." In fact, the Court in Teamsters

reaffirmed its earlier holding in Franks v. Bowman Transpor-

ation Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976), that §703(h) does not bar

the award of retroactive seniority relief. Id_. , at 347.

See also James v. Stockham Valves & Fittings Co., 559

F.2d 310 (5th Cir. 1977). The Court in Teamsters, supra,

made plain that its opinion did not invalidate those Title

VII cases wherein retroactive seniority was allowed, pro

vided that the bona fides of the seniority system could not

be established.

Concededly, the view that §703(h) does not

immunize seniority systems that perpetuate the

effects of prior discrimination has much

support. It was apparently first adopted in

Quarles v. Phillip Morris, Inc., 279 F.Supp.

505 (E.D, Va.). The court there held that "a

departmental seniority system that has its

16/ See Joint Brief of All Appellants p. 35.

26

genesis in racial discrimination is not a bona

fide seniority system." Id_. , at 517 (first

emphasis added). The Quarels view has since

enjoyed wholesale adoption in the Courts of

Appeals. See e.g.f Local 189, United Paper-

workers v. United States, 416 F.2d 980, 987-

988 (CA 5); United States v. Sheet & Metal

Workers Local 136, 416 F.2d 123, 133-134 n.20

(CA 8); United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp. ,

4 46 F . 2d "652, 6"S8"-6"S9 (CA 2)'; United States v .

Chesapeake & Ohio R. Co., 471 F .2d 582, 587-588

(CA 4). Insofar as the result in Quarles and

in the cases that followed it depended upon

findings that the seniority systems were them

selves 'racially discriminatory' or had their

'genesis' in racial discrimination," 279 F.Supp.

at 517, the decisions can be viewed as resting

upon the proposition that a seniority system

that perpetuates the effects of pre-Act

discrimination cannot be bona fide if an

intent to discriminate entered into its very

adoption.

Teamsters, supra, 424 U.S at 347, n.28.

When the parties to this lawsuit agreed to settle rather

than litigate the issues raised by plaintiffs' lawsuit, the

defendants gave up their right to litigate the issue of

whether or not there was pre-Act and/or post-Act discrimina

tion or whether the seniority system was bona fide in exchange

for avoiding the uncertainties and burdens of further

litigation. Likewise, the plaintiffs waived their right to

litigate the issues that they raised as well as a substantial

portion of the back pay they might have obtained, in exchange

for a negotiated settlement. Thus the parties settled the

evidentiary issues raised by Teamsters, and unlike judgments,

settlements are not subject to attack under Teamsters. See

Dawson v. Pastrick, 600 F .2d 70, 76 (7th Cir. 1979). See

- 27

also Sarabia v. Teledo Police Patrolman's Assn./ 601 F .2d

914, 919 (6th Cir. 1979).

If however the Court in Teamsters had held that retroactive

seniority relief was no longer available under Title VII then

the defendants' argument might be said to be analogous to the

cases they cite. However, Teamsters only established an

additional evidential burden which defendants would have had

to meet in order to prevent plaintiffs' relief from impacting

on the seniority system.

The case at bar is in no way analogous System Federation

No. 91 v. Wright, 364 U.S. 642 (1961) or Theriault v. Smith,

523 F.2d 601 (1st Cir. 1975). In System Federation No.

91 v. Wright, supra, the parties entered into a consent

decree enjoining the defendant railroad and railroad labor

unions from discriminating against the plaintiffs and their

class by reason of their refusal to join or retain membership

in any labor organization. The decree was entered at

a time when the Railway Labor Act barred a union shop.

Subsequently, the act was amended to permit a contract

requiring a union shop. As a result of that explicit and

substantive change in the law the Supreme Court held that

the continuing enforcement of the provision no longer

served to further the objectives of the Act and therefore

held that the lower court had erred in refusing to so

modify the consent decree.

28

Similarly in Theriault v. Smith, 523 F .2d 601, 602

(1st Cir. 1975), the Court of Appeals held that the consent

decree was based on an interpretation of the law that the

Supreme Court held to be invalid.

That decree contained the undertaking that

'Defendant beginning August 1, 1974 will, pur

suant to 42 U.S.C. §602(a )(10) and 42 U.S.C.

§606(a) grant AFDC benefits ... to otherwise

eligible women ... on behalf of their unborn

children.' As the Court made clear in [Burns v .]

Alcala, [420 U.S 575 (1975)] the referenced

provisions do not authorize such benefits.

Defendant is therefore precluded from granting

such benefits under their authority.

The essential distinction between the effect of Teamsters

on the instant case, and the situations posed in System

Federation No. 91, supra, and Theriault, supra, is that

Teamsters, supra did not invalidate the type of relief

obtained in the Consent Decree. Rather, the Court in

Teamsters, supra, merely clarified the proof required before---------- — — y y

a court could impose that remedy.

Because all the parties to this litigation, the plain

tiffs, the company and the unions, voluntarily entered into a

17/ The defendants' citation of Myers v. Gilman Paper Corp.,

5T4 F . 2d 837 (5th Cir. 1 977) reversed and vacated in part,"

556 F .2d 758 (5th Cir. 1977), and Southbridge Plastics

Division v. Local 759, Rubber Workers, 565 F .2d 913 (5th

Cir. 1978) is even more far afield. The principal difficulty

in both those cases was that the settlement agreements were

imposed over the vigorous objection of the unions that were

party defendants to the actions. In the case at bar all of

the necessary parties agreed to the seniority relief embodied

in the consent decree, and cannot now be heard to complain

that they were not represented.

29

consent decree, there was never a determination as to

whether or not St. Regis' seniority system was bona fide.

However, the defendants would have this Court assume at this

late date that the seniority system was bona fide and that

therefore mill seniority relief was inappropriate. Such a

determination would be inappropriate for several reasons.

First, as this Court has consistently held:

... it is clear that there is great em

phasis in Title VII on private settlement

and elimination of unfair practices without

litigation.

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach, 398 F .2d 496, (5th Cir. 1968);

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metal Co., 421 F .2d 888, 891 (5th

Cir. 1970). See also U.S. v. Allegheny Ludlum Industries,

517 F.2d 826, 846 (5th Cir. 1975), cert. denied, 423 U.S.

1056 (1976); Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co., 406

F.2d 399, 402 (5th Cir. 1969). Moreover, as the Tenth

Circuirt held in EEOC v. Safeway Stores, Inc., ___

F . 2d ___ 21 EPD 1130,456 p. 1 3,59 5-6_( 1 0th Cir. 1 979):

A Consent Decree would be worthless if it could

be attacked on the ground that had the Court

made a particular determination, such relief

would then not be statutorily available.

See also Dawson v. Pastrick, 600 F .2d 70 (7th Cir. 1979).

Similarly, there is no basis whatever for assuming that any

court might reach a determination that the defendants' senior

ity system was bona fide or racially neutral. The defendants'

employment policies and practices were at the time this

lawsuit was filed indistinguishable from those throughout

30

the southern paper industry which have regularly been found

to be discriminatory, see, e.g. , Watkins v. Scott Paper

Co., supra; Stevenson v. International Paper Co., 516 F .2d

103, 111-118 (5th Cir. 1975); Long v. Georgia Kraft Co., 480

F.2d 557 (5th Cir. 1971); Local 189, United Papermakers &

Paperworkers v. United States, 416 F .2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969),

cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970); Boles v. Union Camp,

supra; Myers v. Gilman, 10 FEP Cases 213 (S.D. Ga. 1974);

Miller v. Continental Can Co., supra; Rogers v. Interna

tional Paper, 510 F.2d 1340 (8th Cir. 1975), vac'd

and ren'd, in light of Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 423

U.S 809 (1975), new trial directed 526 F .2d 722 (8th Cir.

1975).

Finally, the documented history of the southern paper

industry makes plain the discriminatory impact of the

seniority system when combined with the discriminatory

hiring policies generally in effect throughout the industry:

Since, however, Negroes were before 1960 almost

universally denied entry into many lines of pro

gression, they did not have the opportunity to

exercise seniority nearly as broadly as did

whites. Thus, a white worker with much less

mill seniority than a Negro would be working

while the Negro was unemployed because the white

employee had had an opportunity to move up a

progression and there to exercise occupational

seniority. Moreover, long-service whites could

also exercise mill seniority at the base-rate

jobs. Thus whites had two bites at the seniority

apple on a proportionally much larger basis than

did Negroes.

31

H. R. Northrup, (L. Rowan, D. T. Barnum and J.C. Howard,

Negro Employment In Southern Industry, volume IV, Part

I, at 51 (1979).

18/

Unlike the situation posed by Teamsters, historically

virtually all the workers locked into undesirable jobs in

the southern paper industry were blacks. Defendants com

pletely ignore this fact and urge that the collective bar

gaining agreements protect all the workers. However, it

is abundantly clear that whites in the paper industry were

never prevented from accumulating seniority in the desirable

lines of progression.

This fact undercuts any notion that the Court below

failed to consider the impact of its decision on the collec

tive bargaining agreements or the policies of the National

Labor Relations Act. On the contrary, the Court below

repeatedly questioned the parties on the effect his ultimate

decision would have on the collective bargaining agreements.

Tr. 81-86; 87-88; 94-96.

11/Moreover, whatever "competing interests" that

may be said to exist between the NLRA and Title VII were

18/ This Court's recent opinion in James v. Stockham Valves

& Fittings Co., supra, 559 F .2d at 310, makes plain that

Hthe totality of the ~circumstances in the development and

maintenance of the system is relevant to examining" the

bona fides issue.

19/ See, Joint Brief Of All Appellants p. 35.

32

fully harmonized when all of the parties agreed to the

consent decree. In fact the company's chief counsel con

ceded as much during the hearing before Judge Scott:

Hr. Farmer: There's no question, I think,

that all the parties would agree that, during the

period of the consent decree, when it was effec

tive, that it superseded any conflicting provision

in the collective bargaining agreement. Tr. 88.

Thus, this situation is not analogous to Myers v. Gill-

man, supra, as here all the parties agree that if the mill

seniority provisions of the decree remain in effect, then

they would continue to override the collective bargaining

agreement. This was part and parcel of the settlement

reached by the parties in this case. Moreover, mindful

of the potential conflict in this area the District Court

continually questioned the parties on the impact his

decision would have on the collective bargaining agreement.

And, it was not until he was satisfied that the consent

decree explicitly overrode the collective bargaining

agreement that he dropped this line of inquiry.

The District Court's opinion, after properly weigh

ing the context in which the consent decree was approved;

attempting to construe sections II.B, and XVI in the light

of other portions of the agreement, and the competing

interests of all the effected parties, properly held with

respect to section II.B, that, "Nowhere is this provision or

any other expressly limited to any term or period or time."

R.E. 37a.

33

In Bing v. Roadway Express,Inc., 485 F .2d 441, 450 (5th

Cir. 1973), which this Court recently quoted in James v .

Stockham Valves & Fittings Co., supra, 559 F .2d at 356, this

Court held:

Thus the rightful place theory dictates that we

give the transferring discriminatee sufficient

seniority carryover to permit the advancement

he would have enjoyed, and to give him the

protection against layoffs he would have had

in the absence of discrimination.

See also, Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra, 424

U.S. at 760 n.21.

Thus while the consent decree agreed to by the parties does

not guarantee that all the members of the affected class will

reach their rightful place, the relief it provides certainly

contemplates an effort to make whole past victims of dis

crimination by facilitating their attempt to reach their

rightful place during the remainder of their work lives.

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., supra, Gamble v. Birmingham

Southern R.R. Co., 514 F .2d 678, 683 (5th Cir. 1975).

Moreover, the guarantees that the consent decree does

offer are that a discrete group of men who were denied the

opportunity to accumulate seniority in lines of progression

which were open to their white counterparts would finally

have the ability to compete on an equal basis. Absent the

use of mill seniority members of the affected class solely

because of their race would once more be exposed to demotion

34

and layoff while their white peers, solely because of their

race, would continue to fully exercise their seniority for

the same purposes.

This decree, with its permanent implementation of

mill seniority is fully consistent with the demands of

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., supra, and other cases in

that the relief was limited to a discrete number of em

ployees, and only minimally affected the seniority system of

the plant. To assert as to defendants that after almost a

guarter century of discrimination that five years of mill

seniority is sufficient, not only violates the express

provisions of the decree, but also flies in the face of

reason. As this Court has repeatedly recognized, carry

over seniority is essential not only so that discriminatees

may transfer to the more desireable jobs in lines of pro

gression and bargaining units that were previously closed

to them, but additionally so that they can hold onto those

jobs once they are obtained James v, Stockham Valves

& Fittings Co., supra.

J

35

In the cae at bar the need to give force or effect

to the natural and appropriate language of the consent

decree is no less compelling.

CONCLUSION

For all the foregoing reasons, this Court should

affirm the Decision and Orders of the District Court,

of April 19, 1979.

Respectfully submitted,

' I ' .

1 ■ ■ v//

EARL M. JOHN§ON^.^ "

^ 625 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32202

REESE MARSHALL

201 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32202

BENJAMIN KYLE

1248 West Edgewood Avenue

Jacksonville, Florida 32208

ALGIA R. COOPER

121 1/2 South Monroe Street

Tallahassee, Florida 32301

JACK GREENBERG

CLYDE E. MURPHY

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

Nee York, New York 10019

36

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned certifies that copies of the foregoing

Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees have been served on counsel

for all the parties this 3rd day of March 1989 by first

class mail postage preapid, addressed to:

Guy Farmer

Farmer, Shibley, McGuinn & Flood

1120 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

William L. Durden

Kent, Sears, Purden & Kent

870 Florida First National

Bank Building

Jacksonville, Florida 32202

Michael A. Roberts

St. Regis Paper Company

633 Third Avenue

New York, New York 10017

Joseph S. Farley, Jr.

Mahon, Mahon & Farley

350 East Adams Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32202

Elihu I. Leifer

Terry R. Yelling

Sherman, Dunn, Cohen & Liefer

1125 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

Louis P. Poulton

1300 Connecticit Avenue

Washington, D.C. 20036

Edward Booth

Arnold, Stratford & Booth, P.A.

2508 Gulf Life Tower

Jacksonville, Florida 32207

Benjamin Wyle

Linda Bartlett

110 East 59th Street

Suite 1014

New York, New York 10022