Opinion and Order with Cover Letter

Public Court Documents

August 15, 1975

137 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Working Files. Opinion and Order with Cover Letter, 1975. 1780c0d7-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/42618233-16f1-4070-8ca5-1dce2dc33a5d/opinion-and-order-with-cover-letter. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

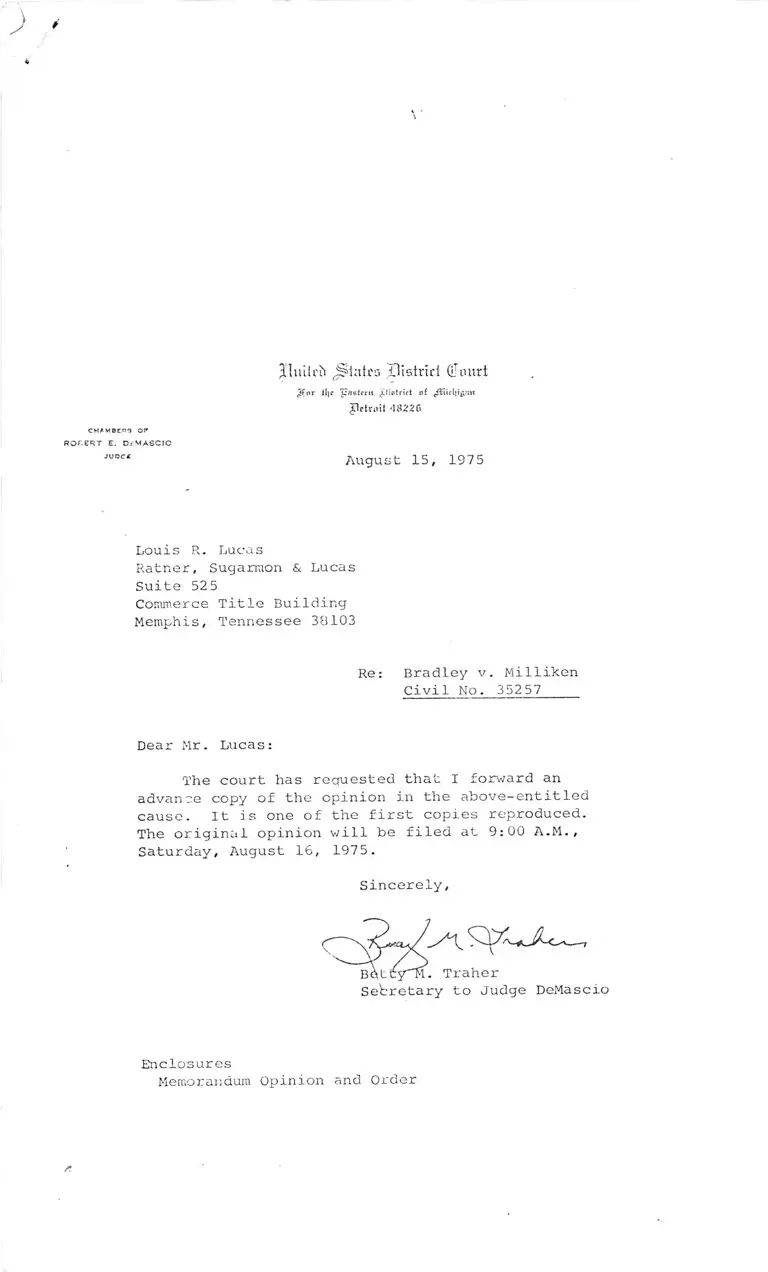

J^iatrs Oistnd Oltutri

Jletniif ‘1S22C

R O B E R T E. D i M A S C I O

August 15, 1975

Louis R. Lucas

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

Suite 525

Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Dear Mr. Lucas:

The court has requested that I forward an

advance copy of the opinion in the above-entitled

cause. It is one of the first copies reproduced.

The original opinion will be filed at 9:00 A.M.,

Saturday, August 16, 1975.

Re: Bradley v. Millihen

Civil No. 35257

Sincerely

Secretary to Judge DeMascio

Enclosures

Memorandum Opinion and Order

C H A M B E R S O F

R O B E R T E . D e M A S C I

J U D G E1

o

Jlnitelt j^tnica ^District QJrmri

^ o r i l]C P i s t r i c t of

Jlctrmt *18226

August 15, 1975

Louis R. Lucas

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

Suite 525

Commerce Title Building

Memphis*, Tennessee 38103

Re: Bradley v. Milliken

Civil No. 35257____

Dear Mr. Lucas:

The court has requested that I forward an

advance copy of the opinion in the above-entitled

cause. It is one of the first copies reproduced.

The original opinion will be filed at 9:00 A.M.,

Saturday, August 16, 1975.

Sincerely,

Enclosures

Memorandum Opinion and Order

*

«. *

TABLE OF CONTENTS*• •

I.

II.

Ill.

iv.

v .

Introduction .............................

Prior Proceedings . . ..................

Findings of Fact

A. The Detroit School System ..........

B. Statistical & Demographic Data . . . .

C. Plaintiffs' Plan ....................

D. Detroit Board of Education Plan . . .

E. Educational Components ..............

F. School Financing ....................

Conclusions of Law

A. General Analysis of Both Plans . . . .

B. Plaintiffs' P l a n ................ - *

C. Detroit Board Plan ..................

D. Plaintiffs'Objections ±o Board's Plan.

E. General Conclusions - Both Plans . . .

Remedial Guidelines ....................

1. Student’Transportation ..............

2. Reading and Communications Skills . .

3. In-Service Training ................

4. Vocational Education ................

5. Testing .............................

I6. Students' Rights & Responsibilities . .

7. School Community Relations ..........

0. Counseling and Career Guidance . . . .

9. Co-Curricular Activities ..........

1

IQ

12

29

39

46

46

38

60

65

73

80

84

87

99

101

103

108

109

111

113

114

10. Bilingual/Multi-Ethnic Studies ........ 115

11. Faculty Assignments .................. 116

12. Monitoring ............................ 118

VI. Conclusion and Appendices.................... 120

«. •

... TABLE OF CONTENTS

I . Introduction............................... X

II . Prior Proceedings......................... 5

III . Findings of Fact .

A. The Detroit School S y s t e m ............. IQ

. , • iB. Statistical & Demographic Data . . . . . 12

C. Plaintiffs' P l a n ....................... 29

D. Detroit Board of Education Plan . . . . 39

E. Educational Components............ .. . 46

. F. School Financing ....................... 46

IV . Conclusions of Law

A. General Analysis of Both Plans . . . . . 58

B. Plaintiffs'Plan........ '............. 60

C. Detroit Board P l a n .................... 65

D. Plaintiffs'Objections ±0 Board's Plan. . 73

E. General Conclusions - Both Plans . . . . 80

V. Remedial Guidelines.................. 84

1. Student'Transportation ................ 87

2. Reading and Communications Skills . . . 99

3. In-Service Training .................. 101

4. Vocational Education .................. 103

5. T e s t i n g ........................ 108

>

6. Students' Rights & Responsibilities . . . 109

7. School Community Relations ............ Ill

8. Counseling and Career Guidance ........ 113

9. Co-Curricular Activities .......... . 114

\

10. Bilingual/Multi-Ethnic Studies ........ 115

11. Faculty Assignments.................. 116

12. Monitoring ............................ 118

VI. Conclusion and Appendices.................... 120

t

s

r.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

ERSTERR DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

, SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plainti ffs,

v.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, Governor

of the State of Michigan and

Ex-Officio Member of Michigan

State Board of Education;

FRANK J. KELLEY, Attorney General

of the State of Michigan;

ALLISON GREEN, State Treasurer;

•MICHIGAN STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION,

a constitutional body corporate,

and its Members;

JOHN W. PORTER, Superintendent

of Public Instruction;

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY

OF DETROIT, a first-class

school district and its

Members; -

GENERAL SUPERINTENDENT OF

DETROIT PUBLIC SCHOOLS;

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS

LOCAL 231, AFT, AFL-CIO,

Defendants.

___________/

Civil No. 35257

MEMORANDUM OPINION AND

REMEDIAL DECREE

(Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law)

DeMascio, Judge

I. INTRODUCTION

Our task in this on-going litigation is to formulate

a just, equitable cad feasible plan to desegregate the Detroit

School System, taking account of the practicalities at hand.

We do so in response to a United States Supreme Court mandate

that we formulate a "decree directed to eliminating the

segregation found to exist in Detroit City Schools." Writing

for the majority of the Supreme Court, Chief Justice Burger

noted that the district court and court of appeals:

". • .proceeded on an assumption that the

. Detroit Schools could not be truly desegre

gated -- in their view of what constituted

desegregation — unless the racial composi

tion of the student body of each school

substantially reflected the racial composi- '

tion [of the metropolitan area]."

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 at 740(1974).

The Chief Justice then pointed out that Swann v. Board 'of

Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ". . .does not require any par

ticular racial balance in each 'school, grade, or classroom'

. . . ." Thus, the Court did not deem it essential to

furnish guidelines for desegregating the Detroit School System.

Cf. Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colo. 413 U.S. 189

(1973). Rather, it left this court to determine what constitute

t

desegregation in this particular school district.

In our analysis, we have been mindful that rigid and

inflexible desegregation plans too often neglect to treat

school children as individuals, instead treating them as pig

mented pawns to be shuffled about and counted solely to achieve

an abstraction called "racial mix." We recognize that our con

cern is with the very young and that a just, equitable and

feasible desegregation plan should not destroy the educational

mission of the schools they attend. We are aware of the adverse

educational and psychological impact upon black children com

pelled to attend segregated schools; to separate them from

other children solely because of skin pigmentation is indeed

invidious. But, although the resulting injury is great, the

remedy devised should not inflict sacrifices or penalties upon

other innocent children as punishment for the constitutional

violations exposed.. We must boar in mind that since those

committing tne grotesque violations are no longer about,

any such punishment or sacrifices would fall upon the very

young; it is the children for whom the remedy is fashioned

who must bear the additional burdens.

The necessity of preserving the educational system

for whom this remedy is addressed has compelled us to scrutinize

carefully plans that are rigidly structured to achieve a racial

mix, that include pairing and clustering of schools, that

fracture grade structures, and that include massive transporta

tion. All of these techniques require children to spend more

time going to school and divert educational dollars and energy

from legitimate educational concerns.

If Detroit's school population were more equally

divided between black and white, or if the desegregation area

were sufficiently large to permit greater equalization, it

would be possible to diminish the inevitable limitations on

the task of eliminating racially identifiable schools in the

district. But it is impossible to avoid having a substantial

number of all black or nearly all black schools in a school

district that is over 70% black. The truth of this statement

is best demonstrated by the desegregation plan offered by the

plaintiffs in this litigation; while plaintiffs contend that

their plan affords the greatest degree of desegregation, their

plan leaves £he majority of the schools in the district between

75% and 90% black. An appropriate desegregation plan must

carefully balance the costs of desegregation techniques against

the possible results to be achieved. Where the benefits to be

gained are negligible, those techniques should be adopted

sparingly.

-1-

Finally, an effective and feasible remedy must pre

vent resegregation at all costs. To ignore the possibility

of resegregation would risk further injury to Detroit school

children, both black and white. In a school district that

is only 26% white, a remedy that does not take account of

. \the possibility of resegregation will be short-lived and use

less if that percentage of whitesfurther decreased, h 'realis

tic desegregation plan should recognize that abuses such as

optional attendance zones, gerrymandered attendance zones,

discriminatory assignments, the bussing of black children

away from closer white schools, and school construction that

knowingly tends to have segregative effects are unlikely to

recur in a school system that has a majority black board of

education and a bi—racial administrative staff.

t

The guidelines adopted by this court consider the

“practicalities of the situation", and at Lhe same time make

"every effort to achieve the greatest degree of actual desegre

gation." Davis v. School Comm'rs of Mobile County, 402 U.S. 33,

37 (1971). The "practicalities" that an appropriate remedy

should consider encompass the legitimate concerns of the school

system and the community at large. One legitimate concern de

serving of weight is the undesirability of forced reassignment

of students achieving only negligible desegregative results.

Another of bhe practicalities is the shifting demography

occurring naturally in the school district together with

the persistent increase in black student enrollment.

Still another of the practicalities to be taken into

account is the racial population of the district, which is

predominantly black by wide margins. Further practicalities

that must' be considered by this court include the declining

tax base of the City of Detroit, the depressed economy of the

-!

City, and the volatile atmosphere cheated by the highest rate

of unemployment in the nation. Finally, the decree must con

sider the overriding community concern for the quality of

educational services available in the school district. An

effective and flexible remedy must contain safeguards that

will enhance rather than destroy the quality of the educational

services provided to the City of Detroit.

II. PRIOR PROCEEDINGS

The Detroit School Desegregation case has been in

litigation for nearly five years. The plaintiffs filed this

action on August 18, 1970, naming as defendants the Detroit

Board of Education, its Members and the Detroit Superintendent

of Schools, together with the Governor, Attorney General,

State Board of Education, and the State Superintendent of

Public Instruction for the State of Michigan. The complaint

alleged inter a3ia that as a result of actions and inactions

on the part of all the named defendants, the Detroit Public

School System was racially segregated. The complaint further

challenged the constitutionality of Act 48 of tlie Michigan

Public Acts of 1970 insofar as that Act precluded implementa

tion of the April 7, 1970, "plan" to desegregate the Detroit

Public Schools. The plaintiffs further prayed for a preliminary

injunction to restrain the enforcement of Act 48 together with

an order requiring the Detroit Board of Education to implement

tlie so-called April ", 1970, desegregation plan.

The district court ruled that plaintiffs were not

entitled to preliminary injunctive relief and declined to rule

on the constitutionality of Act 48. At tliat time, the district

-5-

court granted a motion dismissing the action as to the Governor

«. *\

and the Attorney General. (Rulings dated September 3, 1970.)

Upon 'appeal, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit sustained the district court's denial of plaintiffs'

motion for a preliminary injunction but reversed the district

court in part,holding that portions of Act 48 were unconstitu

tional and at the same time ordering that the Governor and the

Attorney General remain as parties to the litigation. Bradley

v. MiHiben, 433 F.2d 897 (6th Cir. 1970). Although the .

defendant Detroit Board of Education would have implemented the

so-called April 7 desegregation plan upon order of the court or

otherwise, the district court did not order implementation of

such "plan"; instead, as an interim plan, it adopted a plan

submitted by the Detroit Board known as the "Magnet Plan."

(December 3, 1970, Ruling on School jPlans.)

Following a trial on the liability issue, the

district court found that the Detroit School District was

segregated on the basis of race. The court found that certain

conduct on the part of the defendant Detroit Board of Education

and the defendant State of Michigan, through its various state

officials, fostered segregation in the Detroit Public School-

System and violated the Fourteenth Amendment rights of Detroit

school children. The district court also held that the state

was vicariously liable for certain de_ jure acts of the defendant

a IDetroit Board of Education. The district court specifically

found that the state failed until 1971 to provide funds for the

transportation of pupils within the Detroit School System re

gardless of their poverty or distance from the school to which

they were assigned, although at the same time the state provided

financial assistance for student transportation to many

t •V

neighboring, mostly white suburban districts. The district

court finally found that the state, through Act 48, acted

to"impede, delay and minimize racial integration in Detroit

schools." 338 F.Supp. at 589.

The district court thereafter ordered the parties

to submit plans to desegregate the Detroit Public Schools.

Pursuant to this order, the defendant Detroit Board of

Education submitted two plans, referred to as Plan A and

Plan C, that were limited to the corporate limits of the .

City of Detroit. At the same time, the plaintiffs filed a

desegregation plan known as the "Foster Plan" and the State

defendants filed a "Metropolitan School District Reorganiza

tion Plan." Following the hearings conducted on the Detroit-

only plan, the district court concluded that the Detroit Board

of Education Plans A and C were legally insufficient because they

would not significantly desegregate the school system. The

court found that Plan A was an elaboration and extension of the

Magnet Plan then in effect, and further found that Plan C as

submitted by the Detroit Board Weis merely a token desegregation

effort. The district court also rejected the plan submitted by

plaintiffs, specifically finding that plaintiffs' plan would

entail a re-casting of the entire Detroit School System and

would leave the majority of its schools 75 to 95% black, thus

making the Detroit School System more; identifiably black. The

district court then concluded as a matter of law that "under

the evidence in this case [it] is inescapable that relief of

segregation in the public schools of the City of Detroit cannot

be accomplished within the corporate geographical limits of the

city." The Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit affirmed the

-7

district court's ruling on the ibsue of segregation and its

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law on the Detroit-only

plan. The court further affirmed in principle the propriety

of a metropolitan remedy. Following a grant of certiorari

to the Court of Appeals, the Supreme Court, on July 25, 1974,

affirmed the district court's finding on the liability issue

of segregation and did not disturb the court's finding that

the Detroit Public Schools could not be adequately desegregated

within the corporate limits of the city, but reversed the

court's approval of a metropolitan remedy, holding that a district

court may not impose a multi-district remedy to correct a

single school district's acts of de_ jure segregation.

On January 13, 1975, upon receipt of the Supreme

Court mandate from the Court of Appeals, this court filed an

order requiring the parties to file a current status report.

This order precipitated the filing of numerous motions to

dismiss by the intervening suburban defendants. Following a

pre-trial conference on February 18, 1975, the defendant Detroit

Board and the plaintiffs were ordered to submit desegregation

plans for Detroit only, on or before April 1, 1975. The State

defendants were ordered to submit a critique of the Detroit Board

plan by April 20, 1975. On April 16, 1975, the court granted

the motions to dismiss filed by the intervening suburban

defendants and simultaneously granted plaintiffs' motion to

amend their complaint to include allegations of inter-district

de jure violations.

The plan submitted by the Detroit Board contained

many components that were vague or poorly documented. Costs

for these components, including transportation, are excessive.

-8-

\

The defendant Detroit Board sought to add 3,416 new employees,

many at salaries well in excess of its more experienced anc

tenured teachers. Moreover, the plan failed to inform the

court of the extent to which each of the components might

presently exist in the school system. When these deficiencies

became apparent, the court deemed it advisable to appoint

three court experts and commissioned them as officers of the

court to obtain much of the needed information. The court

assigned its experts to obtain from the Detroit Board sufri—

cient data to evaluate the components' included in the plan.

Because the constitutional sufficiency of the defendant- Board s

plan could be determined only by examining all of the alter

natives, the court deemed it necessary to request its experts

to explore additional possibilities! to aid the court s evalua

tion of the transportation component. The hearings on both

plans commenced on April 29, 1975.

■ We now detail the findings of fact in order to

determine the amount of desegregation possible in this

school district, giving due consideration to the practicali

ties at hand. We are reminded that, according to Brown v.

t

Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 300 (1954), this court is

to be guided by equitable principles. Thus, its guidelines

must be flexible and responsive to public and private needs.

r. -9-

Ill. FINDINGS OF FACT .

A . The Detroit .School System

1. The Detroit School System, which is coter

minous with the City of Detroit, is governed by a

Central Board of Education. In an attempt to decentra

lize this huge school system the Michigan legislature,

pursuant to Act 48 of the Michigan Public Acts of 1970

(Mich. Comp. Laws 388.171 et seq.) divided the school

system into eight geographic "regions". Each region is

governed by a regional board of education whose primary

responsibilities and relationship with the central Board

of Education are outlined in Defendant Board of Educa

tion's Exhibit 4, "Guidelines for Decentralization".

Each region has a five-member board■elected by the

citizens residing within its boundaries. The individual

board member receiving the highest number of- votes is

designated chairman of the regional board.

The central Board of Education consists of

13 members. Five of its members are elected from the

City of Detroit at large and the remaining positions

are occupied by the eight regional chairmen. The day-to

day administration of the entire school system is the

responsibility of a General Superintendent of Schools,

an Executive Deputy Superintendent, a Deputy Superintendent

and an Assistant Superintendent, together with eight

Regional Superintendents selected by the regional boards.

The "Guidelines for Decentralization" indicate that there

is much autonomy left with the regional board. For example,

the regional board retains the authority to change attendance

-10-

boundaries within its regiort; transfer teachers from

school to school within the region, vary the educational

curriculum in schools within the region and hire the

Regional Superintendents. Under the regional system

the quality of education could vary not only among

regions but also among schools within a region. Notwith

standing this decentralized system, the central Board of

Education remains responsible for governing the entire

system and for overseeing the actions of the regional

boards.

2. Both the central Board and the central

administration staff under the supervision of the General

Superintendent are bi-racial in character. Nine of the

central Board's thirteen members, including the Board

President, are black; the other four members are white.

At the beginning of this remedial hearing, the General

Superintendent was white and the Executive Deputy Superin

tendent was black; when these proceedings were completed,

the white General Superintendent had retired and had been

replaced by one who is black. The bi-racial aspects of

the school administration extend throughout the entire

staff, down to the level of the department heads.

■ The racial composition of the school admini

stration has changed dramatically since the inception of

I

this lawsuit in 1970. At the conclusion of the trial on

the liability aspects of this litigation in 1971, the

central board was composed of ten white members and three

black members, and the greater part of the General Super

intendent's staff was white. As a result of the

-11-

decentralization brought about by the passage of Act 49,

the black community has become more involved in and has

experienced greater control over the Detroit School System.

3. Although the Supreme Court decision in this

case was handed down in July of 1974, the Detroit Board

of Education did not take steps to formulate a desegrega

tion plan until ordered to do so by this Court. In January

of 1975, however, they created a desegregation office

commissioned to formulate an acceptable plan. The Detroit

Board's plan, submitted to this Coiirt on April 1, 197 5,

was adopted by a 9-4 vote. The nine black members of the

Board voted in favor of the desegregation plan while the

four white members opposed the plan as presented. Although

this vote was split along racialtlines, the Central Board

of Education is nevertheless a cooperative Board and is

willing to desegregate the Detroit school system. However,

the plan as submitted does not enjoy unanimous acceptance

among the members of the Detroit Board, the members of the

administrative staff, or the members of the desegregation

office. It is apparent that under the regional system it

is possible that the degree of desegregation under the

Board's plan could vary among different regions and it is

likely that the plan as submitted by the central Board

of Education enjoys varying degrees of acceptance in

different regions.

B. Statistical and Demographic Data

4. The most recent official racial-ethnic dis

tribution count, taken on September 2.1, 1974, discloses

that there are 257,396 students enrolled in the Detroit

1. •\

Public Schools. Of this number 71.5% are black and 26.4%

are white, while 2.1% comprise other ethnic groups. In

the Detroit School System's regular K-12 program 247,113

students are enrolled, of which 71.4% are black and 28.6%

is comprised of white and other ethnic groups. In the

elementary schools, grades K-6, 141,806 students are

enrolled, of which 72.3% are black and 27.7% is comprised

of white and other ethnic groups. In the junior high

schools, grades 7-8, 39,600 students are enrolled, of

which 73.0% are black and 27.0% is comprised of white

and other ethnic groups. In the senior high school?,

grades 9-12, 65,707 students are enrolled, of which 68.6%

are black and 31.4% is comprised of white and other ethnic

groups. (See Defendant Board of Education's Exhibit 6, page

4.) The racial composition of each region as of September, 27,

1974, is reflected in the table next attached.

I

-13-

«. •V

ETHNIC COMPOSITION

BY REGION

Total Racial-Ethnic Distribution

Region

U vJCi L-I i

Member- American

Indian

Asian

American

Black

American

Spanish

Surnamed

White and ,

Others

ship Num

ber

Per

cent

Num

ber

Per

cent.

Num- 'Per-

ber cent

Num

ber

Per

cent

Num- Ber

ber cent

1 24907 70 0.3 68 0.3 22486 90.3 234 0.9 2049 8.2

2 36972 121 0.3 93 0.3 22278 60.3 3450 9.3 11030 29.8

3 33723 22 0.1 50 0.1 23876 70.8 220 0.7 9555 28.3

4 36820 40 0.1 181 0.5 20414 55.4 145 0.4 16040 43.6

5 31354 7 0.0 16 0.1 30325 96.7 17 0.1 989 3.1

6 30796 37 0.1 48 0.2 19442 63.1 130 0.4 11139 36.2

7 24605 16 0.1 140 0.6 11114 45.2 88 0.3 13247 53.8

8 29725 4 0.0 26 0.1 28300 95.2 66 0.2 1329 4.5

City-Wide

Schools 8494 15 0.1 34 0.4 5883 69.3 107 1.3 2455 28.9

Total

District 257396 332 0.1 656 0.3 184118 71.5

—

4457 1.7 67833 26.4

-14-

5. This Court previously found that the popu-

iation of the City of Detroit peaked in 1950 and since

that year has been declining steadily at the rate of

approximately 169,500 per decade. In 1950 Detroit's

population constituted 61% of the total population of

the standard metropolitan area; in 1970 it comprised but

36% of that figure. The black population in the City of

Detroit has increased markedly from 1.4% of the city

population in 1900 to 43.9% in 1970. 338 F. Supp. 582

at 585-86. The Detroit Board of Education's demographic

1

expert testified, and we agree, that a current study of

Detroit population trends indicates that as of 1975 the

population of the City of Detroit is majority black.

6. On September 27, d971 this Court found that

the decline in the white students in the Detroit Public

School system during the period 1961-1970 was greater than

the percentage decline of the overall white population in

the city. At the same time the percentage of black enroll

ment in the Detroit school system increased at a greater

rate than the overall general black population in the

city during the same period. In the 1960-1961 school year

there were 285,512 students in the Detroit school system,

of which 130,765 (45.8%) were black. In the 1966-1967

»

school year there were 297,035 students in the system,

of which 168,299 (56.7%) were black. In the 1970-1971

school year 289,743 students were enrolled, of which

184,194 (63.6%) were black. During the period between

1968 and 1970 the Detroit school system experienced a «

-15-

V

larger increase in percentage of black students than any

other major northern school district. The percentage

increase in Detroit during that period was 4.7% as con

trasted with a high of 3.2% in Boston and a low of 1.1%

in Denver among other major northern school districts.

(338 F. Supp. 582 at 586.) This court predicted in 1971

that, if present trends continued, the percentage of black

students in the Detroit Public Schools would be 72% in

the 1975-1976 school year, 80.7% in the 1980-1981 school

year, and, further, the system would be virtually 100%

black by 1992. (338 F. Supp. at 585.) The record compiled

during this remedial proceeding demonstrates that the

predictions made by the District Court in 1971 were

1/

totally accurate, if not somewhat conservative. During

the past five years the black student enrollment has

increased at an average of 2% per year, with a corres

ponding 2% decrease in the white student population during

the same five-year period. At the elementary level the

school system is presently 72.5% black and the trend

toward a 2% annual increase has been positively identi

fied.

1/

The District Court in 1971 predicted that in the 1975

1976 school year the black student enrollment would total

72 percent. The evidence taken during this remedial pro

ceeding indicates that that figure was low. Black enroll

ment in the elementary schoools exceeded 72% on September

27, 1974, and black enrollment system-wide on that date

was 71.5%.

-16

7. Thoore arc presently 32 6 schools in the

Detroit Public School System: 226 elementary schools,

56 junior high schools. 22 high schools and 22 specialized

and primary schools, '.’he system operates on a feeder plan

in which elementary students are assigned to specific

junior high and senior high schools. These schools are

distributed throughout the city and form a perimeter

adjacent to outlying suburban areas. The geographic

distribution of schools throughout the system reflects

the Detroit School Sys;em's devotion to the neighborhood

school concept.

The increasing blade student enrollment

in the Detroit Public School System, which extends to

schools located at the city's boundaries, is demonstrated

by the following tables reflecting significant increases

in black student enrollment since 1969: *

*

-17-

School

CARSTENS

GUYTON

HAMILTON

HOSMER

IVES

LINGEMANN

JACKSON J.H.

ROBINSON M.S.

School

COOPER

A. L. HOLMES

CLEVELAND J.H.

GREUSEL J.H.

RACIAL DEMOGRAPHIC SHIFT 1969-1974

OF SELECTED SCHOOLS - DETROIT EASTSIDE

TABLE I \ '

PERCENTAGE BLACK ENROLLMENT

YEAR

1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974

37.4 48.0 62.3 73.2 82.6 88.3

17.2 30.6 49.5 64.1 73.9 77.9

63.6 70.8 71.8 74.2 79.8 83.4

8.2 18.1 28.2 44.8 57.8 70.0

6.2 13.0 19.1 37.9 54.0 64.2

53.1 60.2 62.6 65.8 68.9 72.3

39.8 43.3 54.2 71.9 85.1 92.0

_ — — __ 69.1 84.8 88.7 92 .6

TABLE II

RACIAL DEMOGRAPHIC SHIFT 1969-1974

OF SELECTED SCHOOLS - NORTHEAST DETROIT

PERCENTAGE BLACK ENROLIMENT

YEAR

1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974

59.0 72.1 79.6 85.7 86.9 90.3

86.6 93.2 95.3 96.3 97.8 98.5

68.8 71.6 74.9 74.3 75.9 79.4

69.5 73.6 75.9 70.5 82.2 81.4

-IB-

TABLE III

RACIAL DEMOGRAPHIC SHIFT 1969-1974

ALONG WOODWARD AVENUE* •

PERCENTAGE BLACK ENROLLMENT

■ Year

1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974

School

HAMPTON 68.8 75.1 60.7 70.6 75.3 81.5

Woodward Avenue is a major thoroughfare in Detroit, which

divides the city along east-west lines.

TABLE IV %

RACIAL DEMOGRAPHIC SHIFT, 1969-1974

Or' SELECTED SCHOOLS ON DETROIT'S NORTH SIDE

(BORDERING EIGHT MILE ROAD)

PERCENTAGE BLACK ENROLLMENT

Year

School

1969 1970 1971 1 972 1973 1974

BOW 13.6 17.8 ‘ 27.9 44.7 57.4 68.6

GREENFIELD PK. 32.3 38.2 41.1 46.2 50.7 54.0

MARSHALL 57.3 65.0 69.3 75.1 81.7 84.6

MASON 48.6 52.7 61.6 69.7 77.2 83.5

WINSIIIP 50.1 70.4 89.8 93.3 96.2 97.7

CLEVELAND J.H. 68.8 71.6 74.9 74.3 75.9 79.4

A

-.1 9-

FARWELL J.H. 6 3,3 67.8 68.4 v 68.0 73.9

* * * * it

GRANT J.H. 21.7 26.2t, 27.8 29.7 38.1

HAMPTON J.H. 68.8

*

75.1 95.5 97.1 98.1

PERSHING H.S. 57.7 63.8 73.1 81.0 83.4

* Elementary School Figures.

TABLE V

RACIAL DEMOGRAPHIC SHIFT, 1969-1974

OF SELECTED SCHOOLS IN NORTHWEST-WEST AREA

OF DETROIT

PERCENTAGE BLACK ENROLLMENT

- Year

1969 1970 1971 1972 1973

School

BURNS 31.4 59.8 80.0 90.0 94.5

CADILLAC 17.6 39.1 73.5 75.3 90.9

CRARY 4.5 20.6 40.9 61.9 83.0

DOSSIN . 6.0 5.0 16.8 34.2 64.0

FORD 34.2 35.4 51.8 70.0 84.3

HERMAN 55.6 58.5 66.4 73.9 79.3

McFARLANE 77.6 82.0 89.9 93.9 95.7

NEWTON 14.5 21.8 27.8 45.1 66.9

PARKER 62.7 79.4 88.1 95.1 97.0

PARKMAN 7.8 12.8 29.9 47.8 68.4

COOLEY H.S. 58 .'9 76.3 94.0 97.4 99.3

82.4

41.4

98.8

85.6

1974

97.1

94.4

89.1

80.8

89.6

85.8

96.5

76.9

97.6

78.3

99.6

TABLE VI \-

RACI/vL DEMOGRAPHIC SHIFT, 1969-1974

OF SELECTED SCHOOLS IN DETROIT'S SOUTHWEST AREA

PERCENTAGE BLACK ENROLLMENT

Year

1969 1970 1971 1972 197 3 1974

School

CRAFT 88.4 86.8 84.3 92.1 91.7 91.3

ELLIS 66.9 71.6 74.0 72.5 77.0 83.8

OWEN 69.5 70.8 68.7 67.4 71.5 79.5

r.

-21-

Shifting demographic patterns in Detroit are reflected not

«. •\

only in the schools which are 70% or more black, but also in

those schools which, though not yet majority black, will be so

within a short period:

TABLE VII

RACIAL DEMOGRAPHIC SHIFTS, 1969-1974

IN SELECTED SCHOOLS ON DETROIT'§ NORTHWEST AND

WEST SIDES

Year

School

1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974

EMERSON 3.6 3.6 3.0 8.5 27.7 40.9

MeKENNY 5.1 5.7 10.3 22.2 38.4 4.6.4

COOLIDGE 1.3 2.1 5.1 13.8 30.1 45.6

TABLE: viii

RACIAL

IN SELECTEE

DEMOGRAPHIC SHIFTS, 1969-1974

i SCHOOLS IN NORTHEAST DETROIT

Year

School

1969 1970 ' 1971 1972 1973 1974

GRANT 21.7 26.2 27.8 29.7 38.1 41.4

LYNCH 10.4 6.7 12.8 18.0 30.9 47.8

Based on present trends, it is accurate to expect that the

black enrollment of several schools on Detroit's northwest and

east sides will be in excess of 70% black by the 1975-1976

school year:

TABL1C IX «. •

RACIAL DEMOGRiAPHIC SHIFTS, 1969- 1.974

■

percentag:E BIACK ENROLLMENT

Ye;ar

School

196 9 1970 1971 1972 197 3 1974

BOW 13.6 17.8 27.9 44.7 57.4 68.6

COFFEY — 29.0 33.2 43.6 51.8 68.8

EDISON 0.3 2.7 9.3 25.3 49.5 65.3

HOSMER 8.2 18.1 28.2 44.8 59.8 70.0

The Ford High School whose attendance zone abuts Detroit's

border is located on Detroit's extreme northwest side. As indicated

by.the following table, Ford, presently 55% black, will in all likel

hood be 50% black by the 1975-1975 school year.if demographic trends

continue:

TABLE X . .

RACIAL DEMOGRAPHIC SHIFT 1959-1974 IN

FORD HIGH SCHOOL

PERCENTAGE BLACK ENROLLMENT

Year

1959 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974

13.4 20.0 30.5 40.3 48.2 54.6

-2 3

• ;

Based on current trends, thc\-following schools, which have

student population between 25% and 35% black, can expect to have sub

stantial increases in black enrollment:

_ TABLE XI

RACIAL DEMOGRAPHIC SHIFTS, 1969-1974

PERCENTAGE BIACK ENROLLMENT

School

1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974

GOODALE 0.1 0.7 1.5 4.0 14.9 25.2

MACOMB 1.6 2.8 4.9 8.1 21.0 30.6

EMERSON J.H.

*

3.6

*

3.6

*

3.0 8.4 19.9 30.6

MURPHY J.H. 6.5 9.8 12.7 6.3 20.1 30.3

TAFT J.H. 0.3 0.7 2.4 12.8

t

21.0 34.5

* Elementary school figures

-2 4-

8. These tables clearly demonstrate the City

of Detroit's changing demography and conclusively reflect

significant increases in black student enrollment since

1969. The tables point out that schools that were as low

as 4.5% black in 1969 had increased to as much as 89.1%

black by 1974. The demographic patterns in Detroit reflect

a large number of schools that are 70% or more black and

it is apparent that many schools that are not yet majority

black will become majority black within a short period of

time. For example, Table VII aboVc contains a sampling

of schools located on the northwest side of Detroit-that

will experience a majority black school population within

the coming school year. Similarly, schools located in the

northeast section of Detroit that are presently 40-50%

black will be majority black within the coming school year.

If present demographic trends continue, schools that now

have student enrollment ranging between 20 and 40% black

can expect to have substantial increases in black enroll

ment. Although the vetroit school system as a whole is

experiencing a 2% annual increase in black enrollment, the

following table demonstrates that individual schools in

many areas undergoing racial demographic shifts have

experienced increases in black, enrollment that are as high

as 16.9%'. These shifting demographic patterns are rapidly

changing Detroit's residential patterns; mixed residential

areas may now be found in all parts of the citv, inducing

areas bordering the suburbs.

V -

-2 5-

«. •

\

AVERAGE YEARLY PERCENTAGE

RACIAL CHANGE IN SELECTED SCHOOLS

BETWEEN 1969-1974

PERCENTAGE BIACK ENROLLMENT

Average Yearly Percentage,

School 1969 1974 Change

Emerson 3.6 30.6 5.4

Marshall 57.3 84.6 5.5

Coolidge 1.3 45.6 8.9

Kennedy 64.6 93.1 5.7

Herman 55.6 85.8 6.0

Cooper 59.0 90.3 6.3

Van Zile 46.9 79.7 , 6.6

Parker 62.7 97.6 7.0

Mason 48.6 83.5 7.0

Lynch 10.4 47.8 ' 7.5

McKenny 5.1 46.4 . 8.3

Cerveny 51.5 97.5 9.2

Winship 50.1 97.7 9.5

Carstens 37.4 88.3 10.2

Bow 13.6 68.6 11.0

Ford 34.2 89.6 11.1

Ives 6.2 64.2 11.6

Hosrner 8.2 70.0 12.4

Newton 14.5 76.9 12.5

Edison 0.3 65.3 13.0

Burns 31.4 97.1 13.1

Guyton 17.2 77.9 12.1

Parkman 7.8 78.3 14.1

Dossin 6.0 80.8 * 15.0

Cadillac 17.6 94.4 15.4

Crary 4.5 89.1 16.9

y .

-26-

9. The Board began to undertake steps to

desegregate cs early as 1.97 0 and was precluded from

doing so only by the passage of Act 48 of the Michigan

Public Acts of 1970 (Mich. Comp. Laws §388.171) by the

Michigan Legislature. The Board has followed the policy

of 1 ransporting students to relieve overcrowding in such

a manner as to increase desegregation. In the 1974-1975

school year the Detroit Board was able to increase the

percentage of black students in many schools that had

a low percentage of black enrollment. The table next

annexed demonstrates the dramatic increases in black

student enrollment at various schools accomplished by

such transportation.

»

PERCENTAGE BLACK ENROLLMENT

IN SCHOOLS RECEIVING STUDENTS

TO RELIEVE OVERCROWDING

School

Northwest Area

■ * *

Ann Arb^r Trail

Burgess

Carver

*Dow

Harding

Healy ^

Houghtea

Leslig

Lodge

Mann

Weatherby

Yost

Northeast Area

*Burbank *Hanstein

Marquette*

.McGregor

Pulaski

Robinson _ • *T n x

Wilkins

1974

Without Transportation

2

4

0

32

18

0

4

0

0

14

3

0

0

0

6

0

2

9

0

6

With Transportation

39

21

18

43

22

18

12

32

27

25

16

42

16

23

12

34

14

9

24

16

* Schools which abut the Detroit city limits.

r.

-28-

C. P la in t i f f s 1 P lain

10. The Plaintiffs' desegregation plan, submitted

on April 1, 1975, pursuant to an order of this court and

revised on April 30, 1975, was designed by Dr. Gordon

Foster, Director of the University of Miami Title IV De

segregation Center. The plan as devised by Dr. Foster

deals solely with pupil reassignment. The rationale and the

ultimate goal of the plan are that, as far as possible,

every school within the district must reflect the racial

ratio of the school district as a whole within the limits

of 15 percentage points in either direction. Dr. Foster

admitted that the 15% figure was arrived at arbitrarily.

Under Dr. Foster's definition, any school whose racial

composition varies more than 15% in either direction from

the Detroit system-wide ratio is racially identifiable.

Accordingly, an elementary school with 57.3%-87.3% black

enrollment, a junior high school with 58.0%-88.0% black

enrollment, and a senior high school with 51.9%-81.9%

black enrollment are desegregated schools. Carrying

Dr. Foster's plan a step further, an elementary school

that is 56% black is a racially identifiable white

school and an elementary school that is 85% black is

a desegregated non-racially identifiable school.

(Plaintiffs' plan, p. 7A.)

11. In developing Plaintiffs' plan, Dr. Foster

testified he explored the extent to which desegregation could

be affected by each of the following commonly accepted

in facility utilization. Under the Plaintiffs' plan,

present high school juniors, although included in the

pupil assignment process, are given the option of re

maining at their present school and graduating there,

assuming that to do so would not cause or maintain

. 1

segregation. (Plaintiffs' plan page 5A.)

12. Under the Plaintiffs' plan, not only are .

many students reassigned to elementary schools outside

of their neighborhood for half of their elementary years,

but, as a result of the pairings and changes in feeder

patterns into junior and senior high schools, many .

students will attend a school out of their home neighbor

hood for between eight and eleven years. See, e.g .,

Plaintiffs' plan for Webster, Birney, Peck, Amos, Beard,

Larned, Higginbotham, Glaser and McGregor schools.

Under Plaintiffs' plan only the racial ratio that could

be achieved by a particular pairing was considered in the

selection of schools for the pairings. Consequently, the

Plaintiffs' plan creates many problems relating to building

capacity. For example, proposed enrollment exceeds school

2/

capacity at 18 junior high schools. In addition, some

elementary school pairings under the plan would result in

over-enrollment. While Plaintiffs' plan attempts to minimize

y - ~ ~ ‘

In addition, under Plaintiffs' plan, the Columbus Junior

High School would be over capacity were it not for the

utilization of temporary spaces.

-31-

«. -

techniques: redrawing zone lines between contiguous

zones of differing racial composition, pairing schools

within these zones, pairing non-contiguous zones,

changing feeder patterns in affected schools, examin

ing various building utilization techniques, use of

temporary space, and changing grade structures in parti

cular buildings. Dr. Foster examined these alternatives

in an effort to achieve his desired racial mix. There

after, he subdivided the system into five clusters

with similar racial compositions, each containing a group

of high school constellations. (Plaintiffs plan page 3A,

4A.) Dr. Foster proceeded to alter the grade structures

at particular schools within each cluster, and schools

Iwithin the clusters were then paired. The pairing of

schools was accomplished by selection of all the "racicilly

identifiable" white schools and the "racially identifiable"

black schools in order of size and percentage of children

by race. Thereafter, children in the newly created pairings

were exchanged to achieve ratios conforming to Dr. Foster's

definition of a desegregated school. The plan also created

new feeder patterns for junior and senior high schools

that ultimately achieve a racial mix falling within the

same parameters.

Plaintiffs' pupil reassignment plan does not

include kindergarten and pre-kindergarten children; pro

vision has been made for them to attend the school nearest

their home, which in many instances necessitates changes

-30-

problems of capacity by creating "swing grades" with

the variable assignments of the 6th, 7th and 9th grades, this

technique results in undue disruption of grade structures.

At the senior high school level, the Plaintiffs' plan has

avoided problems of capacity by assuming a dropout correction

factor of .7069 for blacks and .9426 for whites and others.

(Plaintiffs' plan, p. 6A.) As a result, there would be

13,865 fewer blacks and 1,145 fewer whites in the three

senior high grades than in the three junior high grades.

However, no evidence was presented that justifies reliance

upon such a dropout factor; consequently, capacity problems

may be created by Plaintiffs' plan at the senior high school

level as well. Reliance upon a 30% dropout rate for black

students at the senior high school level would disrupt the

entire school system if theprojected number of dropouts

did not materialize. Moreover, even if such a .statistic

were supported by credible evidence, Plaintiffs have not

allowed for the possibility that the dropout rate would

decline in a desegregated system. .

13. We find that a largo number of schools are

paired solely to achieve a desired racial ratio in each

of the paired schools. (Tr. Vol. 18, p. 45.) The

arbitrary pairings devised in Plaintiffs' plan necessitate

the transportation of thousands of black school children

many miles to schools that still remain 80% or more black.

-32-

V

Plan

Paqe SCHOOL 1974 PROPOSED

8 Ellis 83.8 83.0

15 Higginbotham 100.0 82.7 '

27 Keith Primary 99.6 82.6

30 Bellevue 96.7 82.1

28 Krolik 100.0 81.8

12 Alger 100.0 81.6

11 ‘ McFarlane 96.5 81.4

13 Cadillac 94.4 81.0

1 Woodward • 99.9 81.0

4 Chaney 98.3 80.7

1 Roosevelt • 99.9 80.7

9 Monnier 97.0 ' 80.4

4 Goldberg 98.9 80.4

14 Dossin 80.8 80.8

2 Turner 99.4 80.1

4 Owen 79.5 80.0

It is apparent that, for example , Plaintiffs' selection

of the Lingemann School vvas made solely because white

students were needed for transfer to the Bunche School

to accomplish Plaintiffs ' desired balance. Presently,

the Lingemann School is 72.3% black and thus is a deseg

school by Plaintiffs' definition . After application of

Plaintiffs' plan Lingemann School becomes 83.'1% black.

-34

\

Lingemann v;as included in Plaintiffs' plan irrespective

df the fact that it is located in a naturally integrated

neighborhood that has attained a measure of racial sta

bility. The Plaintiffs' plan groups the Craft, Ellis,

Glazier and McKinstry Schools and transports 753 students;

as a result, the Ellis School is reduced from 03.8% to

83.0% black. In the Carrie, Morley and Peck School

grouping, the Carrie School is presently 58% black and

thus not racially identifiable according to Plaintiffs'

definition. After transporting children, Carrie is

reduced to 54.1% black; black students are bussed out of

Carrie solely to be added to the black population at

Morley.

In addition, after transporting thousands of

students, there are a number of schools that are under

or barely exceed the acceptable minimum percentage devised

by Dr. Foster. The following table demonstrates the racial

mix achieved at selected schools:

V

Plan

Page SCHOOL % black

5 Amos 50.7

10 Carver 52.0

21 Richard 52.4

16 * Cooke 52.5

13 Houghton 53.4

6 Higgins 54.1

7 Cary 54.1 .

22 Trix 54.9

. ■ ■-.* .

-35-

t •

V

P1 a n

Page SCPOCi. Black >

•31 Burbank 55.1

.31 McGregor 55.4

6 ' Bennett 55.8

1 Webster 56.1 >ol

17 Larned 56.1 -

19 Burt 57.1

13 Yost 57.4

23 Grayling 57.4 ;

6 I arms > 57 . 6 -

20 Law 58.1 .

10 McColl 58.5 7A.

10 Maybee 55.5 ip-

23 Greenfield Union 58.6 p

9 Everett 58.6 .her

23 White 56.3 :

27 Clark 59.0

3 Burton 59.4

19 . J'olcomb 59.4

22 Fleming 59.5 :k-u;

13 Edison 59.9

3 Beard 60.0 . ,ent

Groupings of schools with comparable racial ratios remain

>

even after the application of Plaintiffs' plan. Schools

containing enrollment over 80t black are grouped in a

contiguous area and follow a consistent pattern. Similarly,

-3 6-

.»* ■ '•'* ■■

«. ■

schools with enrollment under (>0% black are grouped in

contiguous areas and follow an easily discernible pattern.

(See Defendant Board of Education's Exhibit 10.)

. 14. The Plaintiffs1 reassignment plan requires

the transportation of 77,303 children, of which 48,312 are

elementary school children and 28,991 are junior high school

children. Deducting 5,954 children presently being trans

ported, Plaintiffs have arrived at a total of 71,349

students requiring transportation under their plan as

3/ *

proposed. Thereafter, the Plaintiffs use a factor of four

daily round .rips per ius with 6G pupils per bus and esti

mate that 271 additional busses would be required to•

effectuate their reassignment plan. (Plaintiffs' plan p. 7A.)

There is no credible evidence to support Plaintiffs' assump-

{

tion that every bus could be utilized to make four round

trip runs. The Plaintiffs' estirn Le of 271 busses is further

dependent upon the unrealistic assumption of utilizing one

pick-up point for 66 school children without consideration

of the distances students would have to walk to arrive at

the pick-up point. Mo: .over, their estimate does not con

sider the ethnic composition of any area surrounding a pick-up

point.

Plaintiffs' present estimate of 77,303 students

_ -

Vie have 'arrived at varying estimates that range between

77,000 and 01,000 students requiring transportation under

Plaintiffs' plan.

-37-

is not far below their 1972 estimate of 82,000 children

■

requiring transportation. The most credible estimate of

the number of buses required foi Plaintiffs' 1972 plan

was 900. Expert testimony given in 1972 estimated that

a school district could transport an average of 100 students

for each bus in service. (Witness Kuty, Tr. page 122-124,

book 2; March 15, 1972.) Based upon this testimony, which

was not challenged by Pla . Lffs, Plaintiffs' plan would

require the procurement of approximately 840 buses,

including sufficient spares.

Accordingly, we find that the Plaintiffs' ‘ plan

involves the transportation of thousands of students, the

great majority of whom would be transported from one

predominantly black school to another predominantly black

school, involves bus runs within the city of Detroit of

up to thirty-eight minutes without taking in account time

for loading and unloading, and would result in many children

spending between nine and eleven years as far as five to

twelve mi] as from th ,.r neighborhood.

15. The Plaintiffs' plan, based upon a defini

tion of racial identifiability as beyond a range of 15%

from the system-wide racial mix ,is rigidly structured.

The plan does not consider the past or present demography

I

of the Detroit school district, more particularly ignoring

population shifts that have been occuring over the past

decade. Moreover, the plan does not consider the possi

bility of resegregation in the City of Detroit. Although

Dr. Foster testified that his pi an purports to avoid the

-38-

V

possibility of resegregation, this testimony is premised

upon the assumption that after application of the plan

there would be "no pockets where people can go." (Tr. Vol.

19, page 1G6.) There is no credible evidence in this

record to justify the assumption that adoption of Plaintiffs'

plan would lessen the chance of resegregation within or

without the city; Dr. Foster's testimony fails to take

into account the developed suburban areas that circumscribe

the city. Accordingly we find that the Plaintiffs' plan

does not include provisions for promoting racial stability

and avoiding resegregation. We re-affirm the prior-finding

of this Court that:

"It would be a natural, forseeable and

probable consequence of the implementation

of the Plaintiffs' plan that the trend of

the Detroit schools towards a higher

percentage of black students and a lower

percentage of white students will be

sharply accelerated." (Tr. March 14,

1972, page 504-586.)

D. Detroit Board of Education Plan

16. The Detroit Board of Education submitted a

plan that provided for transportation of approximately

51,000 students. Interwoven into the Board's plan is the

provision for magnet schools at both the middle school and

senior high school levels to aid in attaining maximum

desegregation. The goals of the Board's plan include

establishing maximum effective desegregation, removing

racially identifiable white schools and promoting inter

racial understanding and respect in a diversified school

district. The Detroit Board plan takes into consideration

-39-

t. •

the demography of the Detroit School District, and recog

nizes that the Detro.it School System is now 71.5% black

system-wide (72.3% black at the elementary school level).

The Board plan acknowledges that since 1969, the school

district population has declined from 293,859 to 257,396,

whi cli represents a loss of 36,463 students or a 12% decline.

During this five-year period, the black school population

has increased by 3500 students, and over 40,000 white

students have left the system. Accordingly, only 67,833

white students are presently enrolled.in the Detroit School

System, as compared with 189,563 black students. _

Under the Board plan, the Detroit School

System continues to operate on a feeder pattern. The pan-

ings have been devised to provide that every child will

spend at least a portion of his education either in a

neighborhood elementary school or a neighborhood junior and

senior high school. Although regional lines are crossed in

a few instances, the plan generally respects regional

boundary lines, which were brought about, by the State's

attempt to decentralize the school system.

17. Like the Plaintiffs' plan, the Board plan

explores each of the commonly accepted techniques for

desegregation. Like the Plaintiffs' plan, the Board plan

revamps grade structures at the elementary level by pro

viding that some will accommodate K through 3 and others

K plus 4 through 6, and thereafter pairs various schools,

-40-

providin'; transportation between the schools so paired.

Through this process of pairing and clustering schools,

the Board plan attempts to eliminate racially identi

fiable white elementary schools in Regions 2, 3, 4, 6

and 7. The reassignment plan desegregates the junior

and senior high schools by changing the feeder patterns

that feed into the junior and senior high schools, but

at the same time the plan attempts to respect the concept

of high school constellations made up of neighborhood

elenientar*, schools a d neighborhood junior high schools

feeding into an area high school. Under the feeder*plan

realignment the senior high schools will be desegregated

by September, 1976. Eight senior high schools will remain

unaffected bv the ple,n. >!>'

The Board plan attempts to achieve a 402-60%

black racial mix in the remaining white identifiable school

Although the Board purports not to strive for fixed racial

quotas, we find that it does in fact do so. In develop

ing its plan the Board sought to determine the racial

ratio that provided maximum desegregation while preserving

racial stability. The Board concluded that a racial

mixture between 40% and 60% black provided a healthy

and stable racial mix. The Board's statistical data

demonstrates that where elementary schools in a high

school constellation range from 76% to 95% black, resulting

fecc patterns cause the high school, to become 95% to

100% lilac];: white students simply leave the system.by the

time they reach high school. Birrn .1 irly, the statistical

v -

- 4 1 -

v •

data establish that a racial mixture that does not exceed

k't

60%' black provides a degree of stability. Some of the

pairings selected by the Board plan, particularly in

Region 2, fall below the goal set by the Board only

because of the high percentage of Spanish-speaking

students in these schools, which ranges as high as 2 0%

in some instances. To accommodate this factor the Board

permitted the percentage of black students to fall below

therr target for racial mix.

_ 18. The Detroit Board's phpil reassignment plan

does not affect the schools in Regions 1, 5 and 8. Each

of these three regions will remain over 90% black. The

basic premise of the defendant Board's plan is to eliminate

all of the schools with black enrollment below 25% and

bring thorn to the level of 40-60% black. These schools

are located largely on the outer fringes of the city.

The plan leaves untouched 95 schools, most of which are

y

between 95-100% black and are located within the inner city.

Under the defendant Board's plan many schools will operate

over capacity, while some schools in the inner city will

have substantitxl capacity available. The Board decided

to leave 95 schools untouched principally because the Board

y " ~~

In addition to the 95 schools untouched by the pupil re

assignment portion of the Board's plan, 16 schools that are

already desegregated according to the plaintiffs' definition

are untouched, 0 elementary schools are not paired but are

included in desegregated feeder patterns, and 6 schools are

taken out of service.

-42-

found it impractical to desegregate the student bodies

of these schools "without undue hardship of long distance

travel." The Board’s plan acknowledges that there are

too many black students in the system to provide ail of

item with a desegregated experience while at the same time

maintaining stability.

19. The pupil transportation portion of the

Detroit Board plan anticipates the daily transportation

of approximately 51,000 children between paired schools.

The evidence suggests the need for a fleet of busses ranging

between 335 and 425 66-passenger vehicles. The Defendant

Board has suggested that each bus would make two or three

runs per day. (Defendant Board's Exhibit 28.) However,

as indicated above with respect to the Plaintiffs' plan,

credible evidence lias not been presented by either party

to aid the court in making an accurate determination of

the number of busses needed to transport this vast number of

children. The Detroit Board lacks the experience needed

to manage a transportation fleet and does not have available

the appropriate data needed to devise an efficient trans

portation system. This court found it necessary to instruct

the Detroit Board to produce a sufficient data base to per

mit a computer print-out of a grid showing the exact racial

I

composition of students of both races in any particular-

area. Such dat., are necessary to develop an efficient

transportation scheme. Moreover, when such data are avail

able, there will be no justification for transporting

children into an area without consideration of the'ethnic

composition of that area.

Transportation under the Defendant Board's

plan involves much shorter distance than the Plaintiffs'

plan. School pairings were made to allow transportation

routes along major thoroughfares.

20. In addition to reassigning pupils between

paired schools the Detroit Board's plan includes a pro

vision to continue certain magnet schools. Pursuant to

an order of this Court on December 3, 1970, each of the .

eight regions created a magnet school, relying upon

voluntary attendance. Although these magnet schools did

not reach the racial mix sought by either the Plaintiffs

or the Defendant Board, they did serve to provide a

desegregated education in each of the regions in which

t k

they were created.

The Board plan also provides for the creation

of four vocational high schools, specializing in medical science,

transportation, construction and the commercial arts. These

four vocational schools will operate under an enrollment

controlled to simulate the system-wide racial composi

tion. In addition, the Board's plan creates two technical

high schools with enrollment open to students throughout

the entire school system, and creates city-wide high schools

with specialized curricula. The enrollment of these schools

I fwill be controlled to conform to the system-wide racial ratio.

The vocational, technical and city-wide schools are designed

as magnet schools to attract students from throughout the

-4 4-

school sys-com as a means of further desegregating the

school system.

. The Board plan further suggests that four

co-curriculum programs be implemented on a city-wide basis

in order to provide additional childr n with a desegregated

school experience. These programs would i; lude music

education, art, physical education and athletics. (Board

plan page 30.)

Finally, the Board plan suggests the creation

of cultural junior hi h school consortiums designed to

provide students from substantially black majority schools

with an opportunity to spend part of their academic week

with white students from other schools in various cultural

centers in the greater Detroit :-::ea. The Board proposes *,■

that these classes be held at the Art Institute, the Detroit

Public Library, the Merrill Palmer Institute, Wayne State ,

University, Shaw College and Lewis Business School.

>

-4 5-

\

E„ Educational Components

*«

21. In addition to the vocational and career

education and the junior high consortium the plan submitted

by the Detroit Board includes the following educational

components:

a. In-Service Training

b. Guidance and Counselling

c. School-Community Relations

d. Parental Involvement

e. Student Rights and Responsibilities

- .f. Testing .

g. Accountability

h. Curriculum Design

i. Bi- lingual Education v-

j. Multi-Ethnic Curriculum

■ k. Co-curricular Activities

The plan as submitted by the Detroit Board

does not distinguish between those components that are

necessary to the successful implementation of a desegrega

tion plan and those that are not. Moveover, the Defendant

Board's plan does not inform the Court of the extent to which

any of these components may currently be in effect in the

Detroit public school system; nor did the Board, either

through its plan or through expert witnesses, provide the

Court with information adequate to permit the Court to

evaluate the budgetary requests made for each of the

components. Accordingly, the Court found it necessary to

obtain a report from Dr. Louis Monacel outlining the

-46-

«. -

extent to which any or ail of these components currently

exist in the Detroit School System. (See "Comparison of

Existing Personnel, Programs, and Activities with the

Personnel, Programs and Activities Required in the Detroit

Public Schools Desegregation Plan.) The court also found

it necessary to seek an evaluation of each of these com

ponents from Dr. Michael Stolee, one of the Plaintiffs'

expert witnesses. Finally, the court found it necessary

to obtain additional information from its court-appointed

experts to permit a proper evaluation of each of the com

ponents proposed in the Board plan. .

22. We find that the majority of the educational

components included in the Detroit Board plan are essential

for a school district undergoing desegregation While it

is true that the delivery of quality desegregated educational

services is the obligation of the school board, neverthe

less this court deems it essential to mandate educational

components where they are needed to remedy effects of

past segregation, to assure a successful desegregative

effort, and to minimize the possib.i lity of resegregation.

In a segregated setting many techniques deny equal protection

to black students, such as discriminatory testing, discrimina

tory counseling, and discriminatory application of student

discipline.' In a system undergoing desegregation,

teachers will require orientation and training

for desegregation. Parents need to be more closely

involved with the school system and properly structured

programs must be devised for improving the relationship

-47-

* •

between the school and the community. lie agree with the

■ V'

State Defendants that the following components deserve

special emphasis: (1) In-Service Training; (2) Guidance

and Counselling; (3) Student Rights and Responsibilities

(See this Court's order, June 13, 1975); (4) School-

Community Relations-Liaison; (5) Parental Involvement;

(6) Curriculum Design; (7) Multi-Ethnic Curriculum; and,

(8) Co-curricular Activities. Additionally, we find that a

testing program, vocational education and comprehensive

reading programs are essential. Ue find that a comprehensive

reading instruction program together with appropriate* remedial

reading classes are essential to a successful desegregative

effort. Intensified reading instruction is basic to an

educational system's obligation to every child in the school

community (Tr. Vol. 19 pgs. 40-41; Vol. 22, pg. 47). Finally,

the Court finds that an effective Court-oriented monitoring

■program is necessary for effective implementation of a deseg

regation plan to assure that delivery of educational services

will not be made in a discriminatory manner.

F. School Financing

23. The Detroit School District receives

operating funds through levying a property tax, a portion of

which is voted by the electors of the school district and a

portion of which is allocated by the Uayne County Tax Allo

cation Board from the .5 mills constitutionally authorized

to be levied without a vote of the electorate. The school

_ -

See State Critique of Detroit Board's Desegregation Plan,

page 39. ‘

-4 8

1 •

\

district cannot levy additional .millago without a favorable

vote of the electorate. The Detroit School District presently

levies 22.51 mills for operating purposes and 2.25 mills to

finance a prior $68 million deficit (pursuant to Public Acts

1 and 2 of lu73) , for a total of 24.76 mills. This tax effort

produces approximately 33% of the school district's total

budget. State aid comprises 47% of the total budget.' The

j

State aid formula is based upon the number of students in the

school district and upon the State Equalized Valuation (SEV)

of property in the district. Additional state aid is pro

vided by special grants in the form of entitlement and

competitive funds. Federal funds orovide the remaining 15%

of the budget. (Tr. Vol. 7, pgs. 87-85; Vol. 25, pgs.

106-107.)

24. The State School Aid Act contains a formula

designed to equalize revenues among school districts to the

extent that disparities are the result of differences in SEV

per pupil among districts. Over the preceding five-year

period Detroit's State Equalized Valuation (SEV) has remained

relatively static while the SEV in the remainder of the State

generally increased. This trend can be explained by the

movement of industry, commercial institutions and people to

the suburbs and the huge amounts of land used for expressways

in Detroit which remove the property from the city's taxI

rolls.

because the nor capita State Equalized valua

tion in Detroit is 50% lower than the average for the 20

largest cities in Michigan, tire school district must levy

additional inillage to obtain a yield eciual to that of the

-40-

other cities. (Tr. Vol VII, p. 108, Defendant Board's

Exhibit 31.) Because of legislation directed specifically

to the Detroit School District, it .is required to operate on

a balanced budget and must file monthly reports with the

State Auditor General. See Mich. Comp. Laws Sections 338.

1233-1240.

25. The total of all Municipal taxes paid by

Detroit citizens translates into a municipal millage

equivalent of 34.83 mills. This is the highest tax burden

in the State and is 55” higher than the State average.

Only 16 cities in the State of Michigan levy an income

tax; among them, Detroit's rate is the highest. However,

Detroit's per capita income tax yield is substantially

lower than the other 15 cities. Moreover, county taxest

paid by Detroit citizens are 14.4% higher than the State

average, and Detroit municipal taxes are 14.6% higher than

the State average.

Detroit taxpayers also have the highest

municipal overburden in the State. (Defendant Board's

Exhibits 30, 33 & 41.) The State offers assistance to school

districts whose municipal overburden (i.e. the total property

tax rate in the district excluding the amount levied for

school operating purposes) exceeds 125% of the State

average (Bprsloy Act, Mich. Comp. Laws Section 333.1125).

The Act is designed to aid school districts throughout the

State that are unable :o raise sufficient tax revenues

because its taxpayers refuse to approve higher millage

requests in the face of numerous other taxes imposed on

the district by*other local taxing authorities.

V

-5 0-

(Tr. Vol. 7, pp. 103-104.) Presently, the municipal

overburden section of the Act is not fully funded by the

Michigan Legislature, but rather is only funded by

approximately 20%. If the section were fully funded, the

Detroit school district would receive an additional

$61,682,000; if it were funded by 50% during the 1974-75

school year, the school system would have received an

additional $18,787,000. (Tr. Vol. 7, pp. 116-120.) Thus,

the State does not supply the Detroit school district with

as much money as the Act provides.%

26. The power equalising section of the State

School Aid Act guarantees that, subject to certain conditions

each school district will have available $975 per student.

If local tax revenue is insufficient to generate this

amount, state aid will fund the balance. Complete funding

of the balance, however, is contingent upon a local school

district millage levy of 25 mills for operating purposes;

where a school district levies a lesser amount, state aid

is reduced proportionately. While 2.25 mills of Detroit's

levy goes to debt retirement rather than operating purposes,

the entire 24.76 mills is counted in the formula for state

aid. However, state aid does not provide operating

revenue to replace the 2.25 mills used for debt retirement.

Thus, the, 24.76 levy produces operating revenue of only

$916 per student in local taxes and state aid. (Tr. Vol.

7, pp. 93-107.)

The Wayne County Tax Allocation Board gives

the school district .64 mills, which is passed on directly

-51-

Since the majority of schoolto the Library Commission,

districts in Wayne County receive 3.65 mills from the

Tax Allocation Board and Detroit receives only 8.01 mills

exclusive of the library allocation, this additional .64

mills should be counted in the State Aid calculation;

however, it is not. If it were, the district, would have

a total levy of 25.40 mills and thus would be entitled to

the maximum state aid guarantee under the power equalizing

section of the Act.

The Detroit School District's millage levy

of 24.76 mills is slightly below the State average of 26.15

mills. However , when this millage levy is added to all

other taxes assessed against a Detroit taxpayer, the tax

burden is greatly in excess of thfe State average. (Tr. Vol.

7, pg. 104; Vol. 24, pg. 147.) This burden has caused

Detroit taxpayers to reject requests for additional millage.

Seven of the ten millage elections over the past eight

years have failed. Of the three successful votes, one

approved replacing a 15 income tax that the School

Board was authorized to levy pursuant to Public Acts 1 and 2

of 1973 with a "r mill property tax; another merely renewed

an already existing 7.5 mills for an additional ten years.

(Defendant Board's Exhibit 40; Tr. Vol. 24, pp. 143-144,

150-151; 'Vol. 7, p. 140.) It can bo reasonably expected

that the already heavy burden upon Detroit taxpayers will

cause them to reject further requests for millage increases

in the near future. ■

27. The cost of education is a function of the

the size of the system, and the Detroi School System, with

an enrollment, of 257,000 students, is the largest school

district in the State of Michigan. Moreover, the fact that

Detroit's ranking for per pupil expenditure is above the

State average is insignificant because per pupil educational