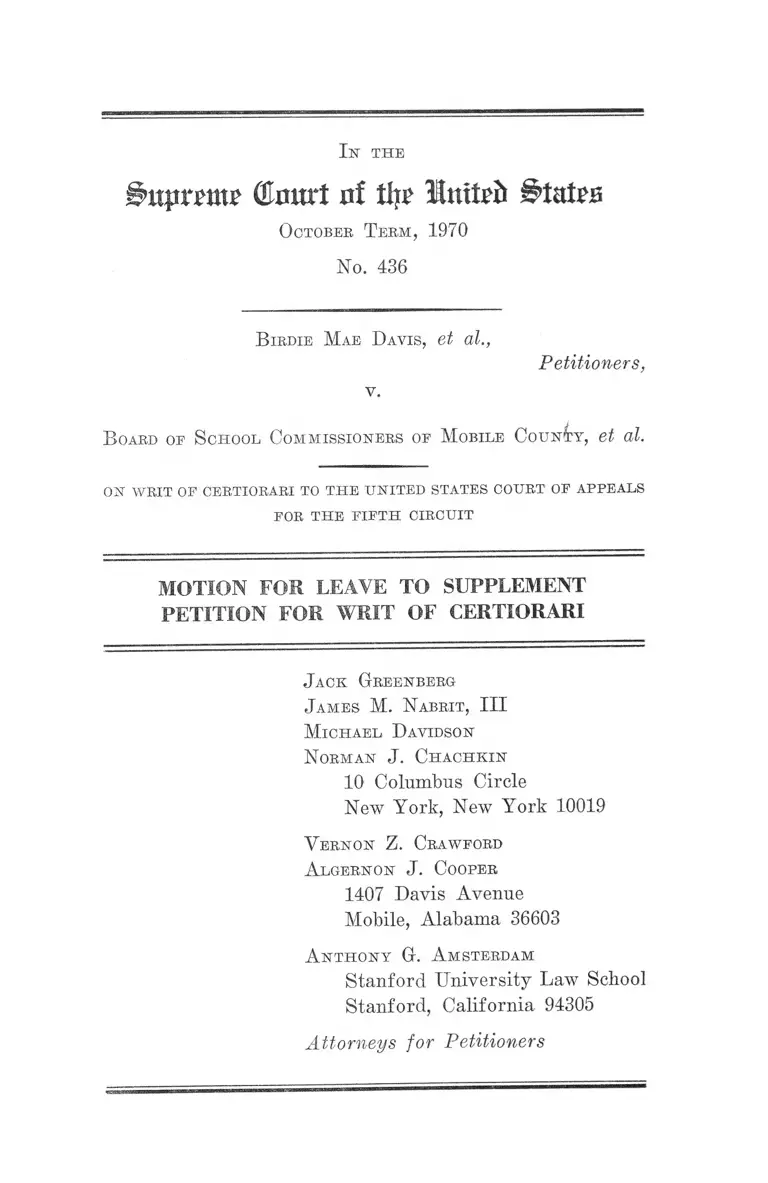

Davis v. Mobile County Board of School Commissioners Motion for Leave to Supplement Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

September 18, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Davis v. Mobile County Board of School Commissioners Motion for Leave to Supplement Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1970. 04b1001c-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/427917b4-2f2a-4ef1-ae2d-8257a8c9acf4/davis-v-mobile-county-board-of-school-commissioners-motion-for-leave-to-supplement-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

(Smirt of tl|P Inttpfc States

October T erm, 1970

No. 436

I n the

B irdie Mae D avis, et al.,

Petitioners,

v .

B oard oe S chool Commissioners of M obile County, et al.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO SUPPLEMENT

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

M ichael D avidson

Norman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

V ernon Z. Crawford

A lgernon J. Cooper

1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

A nthony G. A msterdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

Attorneys for Petitioners

I n th e

iatpmm* (SJmtrt of tip HHniUb States

October T eem, 1970

No. 436

B irdie Mae D avis, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

B oard of S chool Commissioners of M obile County, et al.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO SUPPLEMENT

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Petitioners, by their attorneys respectfully move that

they be permitted to amend or supplement their petition

for writ of certiorari pending herein in order to request

that the Court review the subsequent decisions of the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in this cause filed

on August 4, 1970 and August 28, 1970. The August 4,

1970 order recited that the Court was amending its order

of June 8, 1970:

This opinion and order amends and supplements

our decision and order of June 8, 1970, and together

they shall be considered the final order on this appeal

for mandate and certiorari purposes.

A copy of the August 4, 1970 opinion and order has already

been made available to this Court as it is printed as an

2

Appendix to the Brief In Opposition to Certiorari and

also as an Appendix to the Memorandum of the United

States.

The order entered August 28, 1970 further amends the

orders of the Fifth Circuit. A copy of the August 28th

order is appended hereto, infra.

It is submitted that neither of these recent Fifth Circuit

orders makes any substantial change in the issue presented

for review in this case. The matter is entirely technical

and the purpose of this motion is merely to insure that

the most recent proceedings are technically brought before

this Court.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Geeexbebg

J ames M. Nabbit, III

M ichael D avidsox

Noemax J. Chachkix

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

V eexox Z. Ceaweoed

A lgebxox J. Coopee

1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

A xth o x y G. A mstebdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

Attorneys for Petitioners

3

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that on the 18th day of September, 1970,

I served the foregoing motion on the parties by mailing a

copy to each of the attorneys named below by United States

air mail, special delivery, postag*e prepaid. All parties

required to be served have been served.

Abram L. Philips, Jr.

Palmer Pillans

George Wood

510 Van Antwerp Building

Mobile, Alabama 36602

Samuel L. Stockman

951 Government Street, Room 112

Mobile, Alabama 36604

Honorable Erwin N. Griswold

Solicitor General of the United States

Department of Justice

Washington, D. C.

Pierre Pelham

P. O. Bos 291

Mobile, Alabama 36602

APPENDIX

la

Order of Court of Appeals

(Dated August 28, 1970)

Ik the U kited States Court of A ppeals

F or the F ieth Circuit

No. 29,332

B irdie M ae D avis, et al.,

Plaintiff s-Appellants-Cr oss-

Appellees,

and

U hited States oe A merica, etc.,

Plaintiff -Intervenor- Appellants-

Cross-Appellees,

v.

B oard op School Commissiokers of

M obile. Coukty, et a h ,

Defendants-Appellees-Cross-

Appellants,

and

T wila F razier, et al.,

Interveners-Appellees.

appeals prom the ukited states district court for the

SO U TH E R K DISTRICT OF ALABAM A

(August 28, 1970)

Before B ell, A iksworth, and Godbold, Circuit Judges.

2a

Order of Court of Appeals

B y the Court :—

This Court mandated a plan of pupil assignment for

the Mobile school district in its order of June 8, 1970.

This plan was modified by the district court in its order

dated July 13, 1970. The district court further modified

the plan in an order dated July 30, 1970. On August 4,

1970, we substantially affirmed the modifications made in

the assignment plan by the July 13, 1970 order of the dis

trict court. We did not have the changes embraced in the

July 30, 1970 order before us at the time. Plain tiff s-ap-

pellants have now appealed from the July 30, 1970 order.

The July 30, 1970 order makes changes in the attendance

zones of 32 separate schools. Some of the changes had no

effect from the standpoint of desegregation. Others dimin

ished the degree of desegregation accomplished in the prior

orders of this court and the district court. Most of the

changes can be affirmed on the basis of efficient school

administration and because there is no claim of a racially

discriminatory purpose. It is clear that some of the other

changes cannot be affirmed and that time is of the essence

in resolving the controversy which has arisen over the

July 30, 1970 changes in light of the short time before

school is to commence in Mobile.

The court has considered the motion for summary rever

sal, the memoranda in support of and opposition thereto,

and in addition, a pre-hearing conference with counsel has

been conducted by Judge Bell for the court pursuant to

Rule 33, FRAP. After due consideration, the appeal is

terminated on the following basis:

(1) The middle school and high school zone lines shall

be the same as those set forth in the July 13, 1970

order of the district court.

3a

Order of Court of Appeals

(2) The elementary school zones shall be modified as

follows:

(a) Palmer and Glendale schools shall be paired.

(b) Council and Leinkauf schools shall be paired.

(c) The area of the Whitley zone as described in

the July 30, 1970 order of the district court

that lies west of Wilson Avenue shall become

a part of the Chicasaw zone.

(d) The area in the Westlawn zone as described

in the July 30, 1970 order of the district court

that lies north of Dauphin Street shall become

part of the Old Shell Road school zone.

(3) Counsel for the school board agrees with counsel

for plaintiffs-appellants that they will confer and

make facts available regarding desegregation of

the school system staffs.

(4) Students who refuse to attend the schools to which

they are assigned by the school board under the

order of the district court shall not be permitted

to participate in any school activities, including

the taking of examinations and shall not receive

grades or credit.

(5) Henceforth, any time the school board desires to

have changes in zone lines made, it shall give

reasonable notice to the parties.

The order of the district court of July 30, 1970 is in all

other respects A ffirmed.

It Is So Ordered.

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N, Y. C. 21