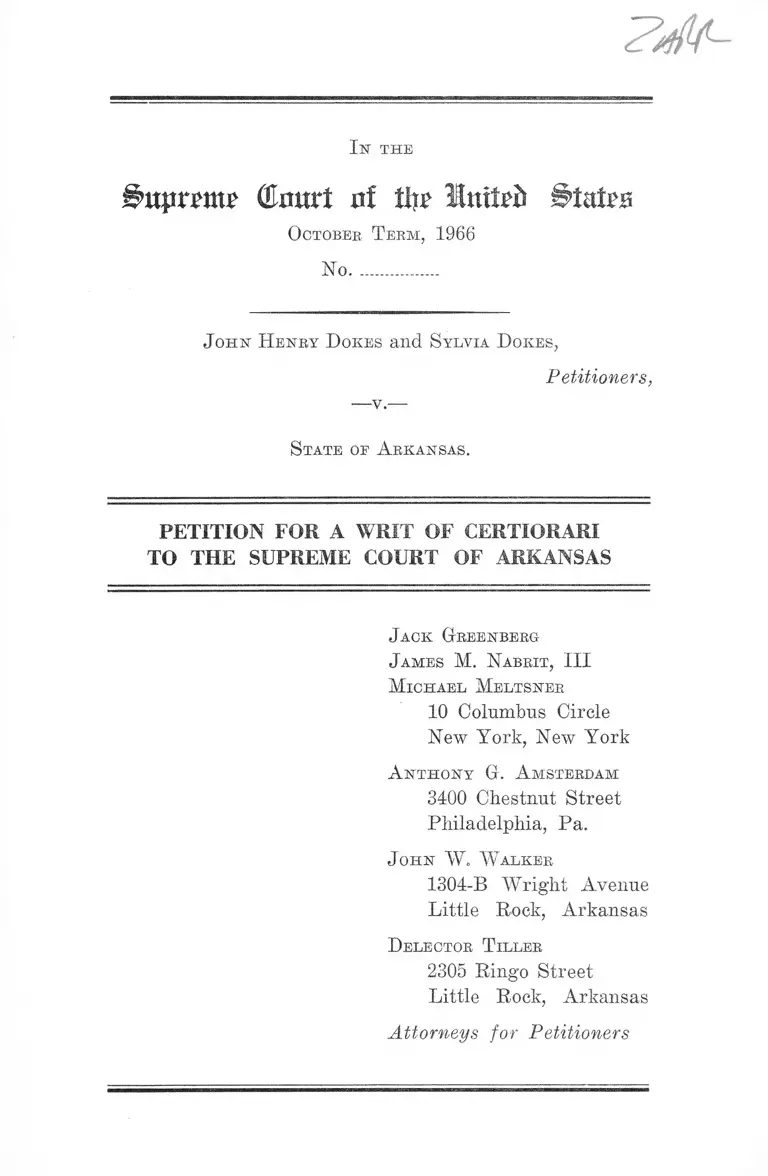

Dokes v. Arkansas Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Arkansas

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dokes v. Arkansas Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Arkansas, 1967. c2810601-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/427d902a-a910-4655-ba84-4ff93af064b5/dokes-v-arkansas-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-arkansas. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

3 # -

Isr th e

(tart rtf tin Btatm

O ctober T eem , 1966

N o .............. .

J o h n H en ry D okes and S ylvia D okes,

Petitioners,

— v . —

S tate of A rk an sas .

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE SUPREME COURT OF ARKANSAS

J ack G reenberg

J am bs M . N abrit , H I

M ic h ael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

A n t h o n y G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa.

J o h n W « W alk er

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas

D elector T iller

2305 Ringo Street

Little Rock, Arkansas

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

Citation to Decision Below .............................. -.... -....... 1

Jurisdiction .......................................................................... 1

Questions Presented ........................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved....... 2

Statement ...................................................... -................... 4

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and De

cided Below ....................................................................... 7

Reasons For Granting The Writ:

I. Arkansas Has Not Met Its Heavy Burden of

Showing a Waiver of Fourth-Fourteenth

Amendment Rights and That the Waiver Doc

trine Was Properly Applied to Excuse the

Warrantless and Unreasonable Nighttime

Search of Petitioners’ Apartment .................. 10

II. The Standards Under Which a State Meets

its Burden of Showing a Waiver of Fourth-

Fourteenth Amendment Rights is a Question

of Public Importance Which Merits the Exer

cise of This Court’s Certiorari Jurisdiction .... 15

III. Petitioners’ Convictions Are Unsupported by

Any Evidence in the Record ............................. 18

IV. Petitioners Were Convicted Under a Contribu

tory Delinquency Statute So Sweeping and

Vague as to Deny Them Due Process of Law

Guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment .... 23

C onclusion .......................................................................................... 32

PAGE

II

A ppen d ix : page

Opinion of Supreme Court of Arkansas .............. la

Denial of Petition for Rehearing .......................... 5a

T able oe C ases

Amos v. United States, 255 U.S. 313 (1924) .............. 13,15

Anderson v. State, Sup. Ct. Op. #156 (File 271);

384 P.2d 669 (Alaska 1963) ..................................... 28,29

Ashton v. Kentucky, 384 U.S. 195 (1966) .................. 25

Brookhart v. Janis, 384 U.S. 1 (1966) .................. 12,13,14

Carnley v. Cochran, 369 U.S. 506 (1962) .................. 14

Carroll v. United States, 367 U.S. 132 (1925) ................ 11

Champlin Ref. Co. v. Corporation Comm’n, 286 U.S.

210 (1942) ..................................................................... 29

Chapman v. United States, 346 F.2d 383 (9th Cir.

1965) ............................................................................... 16

Commonwealth v. Jordon, 136 Pa. Super. 242, 7 x\.2d

523 (1939) .................................................................... 28

Commonwealth v. Wright, 411 Pa. 81, 190 A.2d 709

(1963) ............................................................................. 16

Connally v. General Const. Co., 269 U.S. 385 (1926) .... 31

Davis v. California, 341 F.2d 982 (9th Cir. 1965) ....... 16

Davis v. United States, 328 U.S. 582 (1946) .............. 16

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 (1965) .............. 25

Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1963) .................................. 14

Florence v. Meyers, 9 Race Rel. L. R. 44 (M.D. Fla.

1964) 30

Frye v. United States, 315 F.2d 491 (9th Cir. 1963) .... 16

Gatlin v. United States, 326 F.2d 666 (D.C. Cir.

1963) 1 6

I l l

Gouled v. United States, 255 U.S, 298 (1921) ............. . 15

Griffin v. Hay, 10 Race Eel. L. R. I l l (E.D. Ya. 1965) 30

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) .............. 30

Higgins v. United States, 209 F.2d 819 (D.C. Cir.

1954) ............................................................................... 17

Holt v. State, 17 Wis. 2d 468, 117 N.W. 2d 626 (1962) 16

In re Wright, 251 F. Supp. 880 (M.D. Ala. 1965) ....... 30

Johnson v. United States, 333 U.S. 10 (1948) ....10,11,14,15

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938) ......................12,14

Judd v. United States, 190 F.2d 649 (D.C. Cir. 1951) .... 17

Ker y. California, 374 U.S. 23 (1963) ......................12,15

Landsdown v. United States, 348 F.2d 405 (5th Cir.

1965) 16

Lankford v. Schmidt, 240 F. Supp. 550 (D.Md. 1965),

rev’d on other grounds; Lankford v. Gelston, 364

F.2d 197 (4th Cir. 1966) ............... 10,15

Lavvorn v. State, 389 S.W.2d 252 (1965) ........................ 28

McDonald v. United States, 335 U.S. 451 (1948) ....... 15

McDonald v. United States, 307 F.2d 272 (10th Cir.

1962) ............................................................................... 16

Martinez v. United States, 333 F.2d 405 (9th Cir.

1964) 17

Massachusetts v. Painten, 368 F.2d 142 (1st Cir. 1966) 16

Maxwell v. Stephens, 348 F.2d 325 (8th Cir. 1965) .... 16

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) ..................14,17

Mosco v. United States, 301 F.2d 180 (9th Cir. 1962) 16

hi A A CP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) .................. 25, 29

PAGE

Pekor v. United States, 315 F.2d 319 (5th Cir. 1963) .... 17

IV

People v. Calkins, 48 Cal. App.2d 33, 119 P.2d 142

(1941) ............................................................................. 28

People v. Dritz, 259 App. Div. 210, 18 N.Y.S. 2d 455

(1940) .......................................................................... 28

Reed v. Rhay, 323 F.2d 498 (9th Cir. 1963) .............. 16,17

Rees v. Peyton, 341 F.2d 859 (4th Cir. 1965) .............. 16

Reeves v. Warden, 346 F.2d 915 (4th Cir. 1965) ___ 16

Rivers v. United States, 321 F.2d 704 (2d Cir. 1963) .... 16

Robbins v. MacKenzie, 364 F.2d 45 (1st Cir. 1966) .... 16

Robinson v. United States, 325 F.2d 880 (5th Cir.

1964) ........................................... 16

Rogers v. United States, 369 F.2d 944 (10 Cir. 1966) .... 16

Schultz v. United States, 351 F.2d 287 (10th Cir. 1965) 16

Schware v. Board of Examiners, 353 U.S. 232

(1957) ....................................................................... 22,23

Simmons v. Bomar, 349 F.2d 365 (6th Cir. 1965) ....... 16

Smithson v. State, 34 Ala. App. 343, 39 So.2d 678

(1950) .......................................................................... 28

Spencer v. Texas, 385 U.S. 554 (1967) ........................... 25

State v. Crary, 10 Ohio Op.2d 36, 155 N.E.2d 262

(1959) .......................................................................... 31

State v. Drury, 25 Idaho 787, 139 Pac. 1129 (1914) .... 28

State v. Griffin, 93 Ohio App. 299, 106 N.E.2d 668

(1952) .......................................................................... 28

State v. Hanna, 150 Conn. 457, 191 A.2d 124 (1963) .... 16

State v. Johnson, 145 S.W.2d 468 (Mo. App. 1940) .... 28

State v. Locks, 94 Ariz. 134 382 P.2d 241 (1963) ....... 28

State v. Scrotsky, 39 N.J. 410, 189 A.2d 23 (1963) .......... 16

Stoner v. California, 376 U.S. 483 (1964) ..................... 11

Swenson v. Bosler, 35 U.S.L. Week 3320 (March 13,

1967) ............................................................................... 14

PAGE

V

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U.S. 199 (1960) .......2,19,22

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 (1941) .................... 31

United States v. Arrington, 215 F.2d 630 (7th Cir.

1954) .............................................................................. 15

United States v. Blalock, 255 F. Supp. 268 (E.D. Pa.

1966) .................................... .......................... ................ 14

United States v. Corman, 355 F.2d 151 (2d Cir. 1965) 16

United States v. Evans, 194 F. Supp. 90 (D.D.C. 1961) 17

United States v. Haas, 106 F. Supp. 295, 109 F. Supp.

433 (W.D. Pa. 1952) .............................................. 17

United States v. Hilbrich, 341 F.2d 555 (7th Cir.

1965) 16

United States v. Horton, 328 F.2d 132 (3rd Cir. 1964) 16

United States v. MacLeod, 207 F.2d 853 (7th Cir.

1953) ............................................................................... 17

United States v. Minor, 117 F. Supp. 697 (E.D. Okla.

1953) ............................................................................... 17

United States v. Mitchell, 322 U.S. 65 (1944) ........ 15

United States v. Rabinowitz, 339 U.S. 56 (1950) ........ 11

United States v. Smith, 308 F.2d 657 (2d Cir. 1962) .... 16

United States v. Torres, 354 F.2d 633 (7th Cir. 1966) 16

United States v. Ziener, 291 F.2d 100 (7th Cir. 1961) 17

Yillano v. United States, 310 F.2d 680 (10th Cir.

1962) ............................................................................... 16

Yon Moltke v. Gillies, 332 U.S. 708 (1948) .................. 14

Wallin v. State, 84 Okla. Cr. 194, 182 P.2d 788 (1947) 28

Westbrook v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 150 (1966) .............. 14

Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471 (1963) ....... 11

Zap v. United States, 328 U.S. 624 (1946) ................... 16

PAGE

VI

S tatutes I nvolved

Ala. Code Ann. Tit. 13 §366 (Recomp. 1958) ............ 26

Alaska Stat. Ann. §11.40.130 (1962) ............................. 26

Alaska Stat. Ann. §11.40.150 (1962) .............................. 28

Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. §13-822 (1956) .......................... 26

Ariz. Rev. Stat. §13-823 (1956) ..................................... 28

Ark. Stats. Ann., §45-204 (1964 Replacement) .......3,19, 23

Ark. Stats. Ann. §45-204 .....................................6,18, 25, 31

Ark. Stats. Ann., §45-239 (1964 Replacement) ............ 2

Ark. Stats. Ann. §45-239 ..............................6, 23, 24, 25, 29

Ark. Stats. Ann., §48-903.1 (1964 Replacement) ..4,19,20, 21

Cal. Penal Code (West) §272 (Supp. 1966) .................. 26

Colo. Rev. Stat. §22-7-1 (1963) ............................. 26, 27, 28

Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. §53-254 (1960) ...................... 28,29

Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. §53-254 (1958) .......................... 26

D.C. Code Enc. §16-2314(b) (1966) ............................. 26

Del. Code Ann. Tit. 10 §§901, 1101 (1953) .................. 28

Del. Code Ann. Tit. 11 §431 (a) (3) (Snpp. 1964) ........... 28

Fla. Stat. Ann. §39.01(11) (1961) ................................. 28

Fla. Stat. Ann. §828.21 (1965) ..................................... 26

Ga. Code Ann. §§24-9904, 26-6802 (Repl. 1959) .......26, 27

Hawaii Rev. Laws §330-6 (1955) ..................................... 27

Idaho Code §16-1817 (Supp. 1965) ............................... . 27

111. Stat. Ann. (Smith-Hurd) ch. 23 §2360(a) (Supp.

1966) ............................. 28

111. Stat. Ann. (Smith-Hurd) ch. 23 §2361a (Supp.

1966) 27

Ind. Stat. Ann. (Burns) §9-2803 (Repl. 1956) ......... 28

Ind. Stat. Ann. (Burns) §9-2804 (Repl. 1956) .............. 27

Iowa Code Ann. §233.1 (1949) ........................................... 27

PAGE

Kan. Stat. Ann. §38-830(a) (1964) .............................. 27

Ky. Bev. Stat. >§208.020(3) (a) (1958) .......................... 27

La. Bev. Stat. Ann. (West) Tit. 14 §92.1 (Snpp.

1966) ............................................................................... 27

La. Bev. Stat. Ann. (West) (Tit. 14 §92.1(A) (Supp.

1966) ......... 27,28

Me. Bev. Stat. Ann. Tit. 17 §859 (1964) ..................27, 29

Me. Bev. Stat. Ann. Tit. 17 §860 (1964) ..................28, 29

Md. Code Ann. Art. 26 §§52(e), 78(b) (Bepl. 1966) .... 28

Md. Code Ann. Art. 26 §§53(c), 76(f), 79 (Bepl. 1966) 27

Mass. Ann. Laws cli. 119 §52 (Supp. 1965) .................. 28

Mass. Ann. Laws ch. 119 §63 (Supp. 1965) .................. 27

Mich. Stat. Ann. §28.340 (Bepl. 1962) ......................27, 28

Minn. Stat. Anno. §260.27 (1959) ................................ 28

Minn. Stat. Ann. §260.315 (Supp. 1966) ..................... 27

Mo. Stat. Ann. §559.360 (Supp. 1966) .......................... 27

Mont. Bev. Codes Ann. §10-617 (Supp. 1965) .......... 27,28

Neb. Bev. Stat. §28-477 (Supp. 1965) ......... 27

Neb. Bev. Stat. §43-201 (Supp. 1965) .......................... 28

Nev. Bev. Stat. §201.110 (1965) ................................. 27,28

N.H. Bev. Stat. Ann. ch. 169 §32 (Supp. 1965) ......27,29

N.J. Stat. Ann. §2A:96-4 (1953) ................................ 27

N.M. Stat. Ann. §40A-6-3 (Bepl. 1964) ............................ 27

N.Y. Penal Law §494 ........................................................ 27

N.C. Gen. Stat. Ann. §110-39 (Bepl. 1966) .................. 27

N.D. Century Code Ann. §14-10-06 (Bepl. 1960) ........... 27

Ohio Bev. Code Ann. §2151.41 (1953) ......................... . 27

Okla. Stat. Ann. Tit. 21 §856 (1958) ........................ 27

Okla. Stat. Ann. Tit. 21 §857 (1958) .............................. 28

Ore. Bev. Stat. §167.210 (Bepl. 1965) .......................... 27

B.I. Gen. Laws §11-9-4 (1956) ......................................... 27

V ll

PAGE.

Y l l l

S.C. Code Aim. §16-555.1 (1962) ................................. 27, 28

S.D. Code §43.0301 (1939) ............................................. 28

S.D. Code §43.0409 (1939) ......................................... 27,28

Term. Code Ann. §37-242 (Supp. 1966) ........................ 28

Tenn. Code Ann. §37-270 (Supp. 1966) ... .................... 27

Tex. Penal Code (Yernon) Art. 534a (Supp. 1966) .... 27

Utah Code Ann. §55-10-80(1) (Supp. 1965) .................. 27

Yt. Stat. Ann. Tit. 13 §1301 (1958) ............................. 27

Ya. Code Ann. §18.1-14 (Eepl. 1960) .............................. 27

Wash. Rev, Code Ann. §1304.010 (1962) ...................... 28

Wash. Rev. Code Ann. §13.04.170 (1962) ...................... 27

W. Va. Code Ann. §49-7-7 (1966) ................ 27

W. Va. Code Ann. §49-7-8 (1966) ................................. 28

Wis. Stat. Ann. §48.45(4) (a) (1957) .......................... 27

Wis. Stat. Ann. §48.45(5) (1957) ................................. 28

Wyo. Stat. §§14-7, 14-23(a) (Repl. 1965) .................. 27

O th e r A u thorities

Geis, Contributing to Delinquency, 8 St. Louis U.L.J.

59 (1963) ....................................................................... 26

Gladstone, The Legal Responsibility of Parents for

Juvenile Delinquency in New York, 21 Brooklyn

L. Rev. 172 (1955) ........................................................ 26

Ludwig, Delinquent Parents and the Criminal Law,

5 Vand. L. Rev. 719 (1952) ......................................... 26

Ludwig, Youth & the Law (1955) ................................. 26

Meltsner, “ Southern Appellate Courts: A Dead End”

in Friedman (ed.), Southern Justice 152 (1965) .... 30

Model Penal Code §230.4 (P.O.D. 1962) ...................... 26

PAGE

IX

PAGE

Note, 51 Calif. L. Rev. 1010 (1963) ............................. 16

Rubin, Are Parents Responsible for Juvenile Delin

quency? in Crime and Delinquency 35 (2d ed. 1961) 26

Rubin, Should Parents Re Held Responsible for

Juvenile Delinquency?, 34 Focus 35 (March 1955) .... 26

Starrs, A Sense of Irony in Juvenile Courts, 1 Ilarv.

Civil Rights—Civil Liberties L. Rev. 129 (1966) .... 30

The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society (1967) .... 31

The Standard Juvenile Court Act, 5 N.P.P.A.J. 323

(1959) ............................................................................. 26

U. S. Comm’n on Civil Rights Report, Law Enforce

ment, 1965 ..................................................................... 29

Weinstein, Local Responsibility for Improvement of

Search and Seizure Practices, 34 Rocky Mt. L. Rev.

150 (1962) ............................................' ...................... 17

I n t h e

Ihtprem? (tart of % Inl&fr BMm

O ctober T erm , 1966

No.................

J o h n H en ry D okes and S ylvia D okes,

Petitioners,

—v.—

S tate of A rk an sas .

PETITION FOE A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE SUPREME COURT OF ARKANSAS

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Arkansas entered

in the above-entitled case on December 19, 1966, rehearing

of which was denied January 30, 1967.

Citation to Decision Relow

The decision of the Supreme Court of Arkansas (R. 95-

99) is reported a t ------A rk .------—, 409 S.W.2d 827, and is

set forth in the appendix infra, p. la.

jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Arkansas af

firming petitioners’ convictions was entered on December

19, 1966 (R. 95-99). An order denying petition for rehear

ing was entered by the Supreme Court of Arkansas Janu

ary 30, 1967 (R. 104).

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §1257(3), petitioners having asserted below, and

2

asserting here, deprivation of rights secured by the Con

stitution of the United States.

Questions Presented

1. Whether the state met its burden of proving that a

husband and wife consented to the nighttime search of

their home, the scene of a peaceful and orderly interracial

social gathering, and intentionally and knowingly waived

their Fourth Amendment and Fourteenth Amendment

rights.

2. Whether petitioners’ convictions upon a charge of

contributing to delinquency denied them due process of

law as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment where

the record fails to disclose any evidence that they caused,

encouraged or contributed to delinquency within the mean

ing of the rule of Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U.S. 199

(1960).

3. Whether petitioners may be convicted consistently

with the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

of violating a vague and indefinite contributory delin

quency statute which is susceptible to unpredictable appli

cation against innocent and unpopular persons.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. This case involves the Fourth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case involves the following statutes of the State

of Arkansas:

(a) Ark. Stats. Ann., §45-239 (1964 Replacement)

Any person who shall, by any act, cause, encour

age or contribute to the dependency or delinquency of

3

a child, as these terms with reference to children are

defined by this act, or who shall, for any cause, be

responsible therefor, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor

and may be tried by any court in this State having

jurisdiction to try and determine misdemeanors and

upon conviction therefor, shall be fined in a sum not

to exceed five hundred dollars [$500.00], or imprison

ment in the county jail for a period not exceeding one

[1] year, or by both such fine and imprisonment. When

the charge against any person under this act concerns

the dependency of a child or children, the offense, for

convenience, may be termed contributory dependency,

and when it concerns the delinquency of a child or

children, for convenience it may be termed contribu

tory delinquency. Provided, however, that the court

may suspend any sentence, stay or postpone the en

forcement of execution or release from custody any

person found guilty in any case under this act when,

in the judgment of the court such suspension or post

ponement may be for the welfare of any dependent,

neglected or delinquent child as these terms are de

fined by this act, such suspension or postponement

to be entirely under the control of the court as to

conditions and limitations.

(b) Ark. Stats. Ann., §45-204 (1964 Replacement)

The words “delinquent child” shall mean any

child, whether married or single, who, while under

the age of eighteen [18] years, violates a law of this

State; or is incorrigible or knowingly associates with

thieves, vicious or immoral persons; or without just

cause and without the consent of its parents, guardian

or custodian absents itself from its home or place of

abode, or is growing up in idleness or crime; or know

ingly frequently visits a house of ill-repute; or know

4

ingly frequently visits any policy shop or place where

any gaming device is operated; or patronizes, visits or

frequents any saloon or dram shop where intoxicating

liquors are sold; or patronizes or visits any public

pool room where the game of pool or billiards is be

ing carried on for pay or hire; or who wanders about

the streets in the nighttime without being on any law

ful business or lawful occupation; or habitually wan

ders about any railroad yards or tracks or jumps or

attempts to jump on any moving train, or enters any

car or engine without lawful authority, or writes or

uses vile, obscene, vulgar, profane or indecent lan

guage or smokes cigarettes about any public place or

about any schoolhouse, or is guilty of indecent, im

moral or lascivious conduct; any child committing any

of these acts shall be deemed a delinquent child. . . .

(c) Ark Stats. Ann., §48-903.1 (1964 Replacement)

It shall be unlawful for any person under the age of

twenty-one [21] years to possess or purchase any in

toxicating liquor, wine or beer. It shall also be un

lawful for any adult to purchase on behalf of a person

under the age of twenty-one [21] any intoxicating

liquor, wine or beer. Any person violating this Act

shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor and upon

conviction thereof shall be subject to a fine of not

less than ten dollars ($10.00) nor more than one hun

dred dollars ($100.00).

Statement

On Saturday evening, January 30, 1965, at about 11 P.M.,

Officer Jim Harris (an off-duty Little Rock policeman who

worked as a night watchman for the Little Rock Housing

Authority) observed several automobiles carrying white

5

occupants enter the Booker Home Project (R. 24-25). He

considered this “very unusual” (R. 25) because only Ne

groes lived in the Booker Home Project (R. 31, 39-40). He

did not consider it a violation of the law, but felt he should

investigate (R. 32) even though he would not have made

“as thorough an investigation” had only Negroes been in

the cars (R. 35-36). No complaint of any disturbance had

been made (R. 34-35). Officer Harris called the Vice Squad

and two other officers came to the housing project (R. 27).

Petitioners are married and live in a two bedroom apart

ment in the Booker Home Project (R. 61). At the time of

his arrest, petitioner John Henry Hokes, a Negro, age 23,

was employed at a local department store, along with

James Charton and Paul Sehmolke, both white. Charton

and Sehmolke asked Dokes if they could listen to a Negro

singing group (which he was forming) rehearse at his

apartment (R. 58-59). In addition to the singing group,

Hokes expected only Charton and Sehmolke on January 30,

but he admitted others whom they had in turn invited

(R. 59). A total of twenty Negroes and whites, including

the other members of the singing group, and Claude Taylor,

a young man under contract to a recording company (R.

87) came to the apartment (R. 64), Of these, there were

seven adults and five persons under eighteen years of

age (R. 15-16). James Charton, an adult, brought some

beer and another adult brought a small bottle of rum to

the apartment (R. 60). Mrs. Sylvia Hokes, a Negro, age

22, made herself a drink with the rum (R. 70) but it is un

contradicted that neither she (R. 70) nor her husband

(R. 63) gave any beer or liquor to any of the minors

(R. 82). Huring the course of the evening, Hokes re

quested that his wife get a record player (R. 63, 68). She

and Steve Charton and Kenny Gill (R. 71) two white males,

left the apartment and encountered Officers Harris, Terry

and Parsley outside (R. 31).

6

Officer Terry testified that at about 11:30 P.M. “we

stopped them and took them back to the apartment” (R.

40) and that after he had identified himself as a police of

ficer outside the apartment Mrs. Dokes raised no objection

to his entering (R. 41). Officer Harris stated “ it is pos

sible” that he said “we are police officers, where is the

party . . . Take me to the party” (R. 31). He also testi

fied “ She made no objection to us coming in when we

identified ourselves as police officers” (R. 27).

Petitioner Sylvia Dokes testified that one of the officers

asked where the party was and told her to “ Take us back

where you came from” (R. 71). She denied that she in

vited the officers into her home (R. 71-72).

Inside the apartment, which the officers entered without

a warrant, no one was loud or rowdy or using obscene

language (R. 33, 35). The guests were spread through

out the three rooms (R. 85). None of the officers saw

beer or whiskey in the hands of any person under

eighteen years of age, nor did they see petitioners give

any beer or whiskey to anyone (R. 37, 46, 48, 56). There

were beer cans in the apartment (R. 28) and a 19-year-old

girl was holding Sylvia Dokes’ drink when the officers en

tered the apartment with her (R. 42, 46). In questioning

a person under eighteen years of age, one officer detected

the odor of alcohol on her breath (R. 53). The officers then

arrested all 22 persons in the apartment; the minors were

charged with possessing alcoholic beverages and the adults,

including petitioners, with contributing to the delinquency

of minors pursuant to Ark. Stats. Ann §§45-239, 204 (R.

43, 44).

Petitioners plead not guilty to oral charges, were tried

in the Municipal Court of Little Rock, found guilty and

fined $25.00 plus $10.50 costs each. A de novo trial before

the Circuit Court of Pulaski County, Arkansas on April 8,

7

1966 resulted in a jury verdict of guilty and an increase in

the fines to $200.00 each. The circuit judge directed a

verdict of acquittal for their two codefendants on the

ground that “ it wasn’t their apartment” (R. 56, 80). At

the trial petitioners’ counsel was denied the opportunity

to examine jurors concerning a handbill circulated prior

to trial by The Capital Citizens Council describing an

“interracial rum and beer party” and listing the name, ad

dress, age, sex and race of those arrested in petitioners’

apartment (R. 13, 15, 16).

On appeal, the Supreme Court of Arkansas affirmed the

convictions on December 11, 1966 and denied petition for

rehearing January 30, 1967.

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

and Decided Below

Petitioners filed a motion to dismiss the charge of con

tributory delinquency in the Circuit Court of Pulaski

County, Arkansas (R. 18-19) alleging that they were ar

rested “ solely because they permitted a peaceable inter

racial gathering in their home,” and that they were thereby

denied their federal constitutional rights to peaceably as

semble, due process of law, equal protection of the laws, and

to be free from unreasonable search and seizure, in viola

tion of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

Petitioners also moved to suppress any evidence obtained

from their apartment on January 30, 1965 on the ground,

inter alia, that such evidence was obtained in violation of

their rights under the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments

to the Constitution (R. 20).

The trial judge overruled both motions prior to trial

and again at a hearing held May 23, 1966, subsequent to

trial and conviction (R. 20-A, 23-24). During the course of

8

the trial, the court permitted the arresting officers to testify

as to what they saw inside petitioners’ apartment before

they arrested petitioners.1

Petitioners’ motion for new trial (R. 12-16) raised, among

other questions, denial of their Fourteenth Amendment

rights by unreasonable search, seizure, and arrest and chal

lenged the verdict as contrary to law. The motion was

denied (R. 17).

Petitioners appealed to the Supreme Court of Arkansas,

arguing in their brief that the convictions violated the

Fourteenth Amendment in that:

(1) There is no evidence in the record to support the

convictions.

(2) The statute under which the state proceeded is vague

and uncertain.

(3) The admission of testimony regarding observations

by police officers inside a home entered without war

rant or probable cause violates the Constitution.

(4) Convictions for contributing to the delinquency of a

minor violate the Constitution because no delinquent

minor was ever identified.

(5) The convictions are based upon an information and

charge to the jury rendered inapplicable by statutory

amendment prior to their trial.

(6) The arrest and conviction was motivated by racial

considerations.

The Supreme Court held that there was “no merit in ap

pellants’ contention that there was an unlawful search,”

1 The court refused, however, to permit the introduction of certain

physical evidence seized in petitioners’ apartment, without explanation

(E. 51).

9

for the reason that the constitutional immunity from un

reasonable search could he waived and in its view of the

record, petitioner Sylvia Dokes “waived the right to a

search warrant” (E. 97).

The Court also considered petitioners’ constitutional

claim that “the State failed to prove the necessary facts to

sustain the conviction for contributory delinquency” (R. 97).

It concerned itself first with the proper construction and

scope of the statute challenged as vague, adopting the hold

ing of an earlier decision “that a person may be found

guilty of contributing to the delinquency of a minor, under

our statute, by acts which directly tend to cause delinquency,

whether that condition actually results or not” (R. 98). The

Court then looked to the record to determine whether there

was any evidence (expressly disclaiming any intention to

weigh its sufficiency (E. 97)) to support the convictions

and held they were “well supported by the evidence” be

cause “it is only necessary for the State to prove a condition

or circumstances existing that would tend to cause, encour

age or contribute to the delinquency of a child” (R. 98).

The Court failed to pass on appellants’ remaining “points

for reversal” on the ground that they “were not brought

into the motion for a new trial and cannot be considered

for the first time on appeal” (E. 98).

Petition for rehearing, reasserting petitioners’ federal

constitutional claims, was denied (R. 100-04).

1 0

Reasons For Granting The Writ

I.

Arkansas Has Not Met Its Heavy Burden o f Showing

a Waiver o f Fourth-Fourteenth Amendment Rights and

That the Waiver Doctrine Was Properly Applied to

Excuse the Warrantless and Unreasonable Nighttime

Search o f Petitioners’ Apartment.

This is a case of shocking police misconduct which this

Court should reverse because the official mischief shown

falls so clearly within the scope of the Fourth Amendment.

Acting solely because whites and Negroes of both sexes

peacefully entered an all-Negro public housing project, offi

cers of the Little Rock Vice Squad thrust themselves into a

quiet and orderly social gathering without even a suspicion

of unlawful conduct. Absent the presence of whites and

Negroes at this gathering and, perhaps, its taking place in

a low income public housing project, it is apparent that

the police would not have invaded petitioners’ privacy much

less disturbed it to the extent of arresting petitioners and

their visitors on evidence which does not rise to the dignity

of a criminal violation, see infra pp. 19-23, cf. Lankford v.

Gelston, 364 F.2d 197, 204 (4th Cir. 1966) (Sobeloff, J.).

The only testimony introduced by the State to prove

petitioners were guilty of contributing to delinquency was

that of the police officers as to what they observed after

they entered petitioners’ apartment. Convictions based on

such testimony deny petitioners the protection of the Fourth

and Fourteenth Amendments if the policemen’s observa

tions were made only after an unconstitutional entry of

their home as clearly as if the officers had seized every ob

ject within their vision and such tangible evidence had

been introduced at petitioners’ trial. Cf. Johnson v. United

l i

States, 333 U.S. 10 (1948); see also Wong Sun v. United

States, 371 U.S. 471, 485-86 (1963). In this ease the police

officers had neither a search (R. 35) nor an arrest warrant

(R. 55). There was no reason to suspect that any crime had

been committed (R. 35) let alone probable cause to make an

arrest, prior to their entrance into the apartment. Warrant

less search has occasionally been found reasonable where

“ the surrounding facts brought it within one of the excep

tions to the rule that a search must rest upon a search war

rant,” Stoner v. California, 376 U.S. 483, 486 (1964) but

none of these exceptions are remotely applicable here.2

While arrests were made after the officers had entered

petitioners’ apartment, the arrests even if lawful clearly

do not avail to justify the prior warrantless entry.3 John

2 No moving vehicle was the subject of search. Carroll v. United,

States, 367 U.S. 132, 159 (1925) approves searches o f moving vehicles

upon probable cause “ for belief that the contents of the automobile

offend against the law.” No question o f feared destruction o f contraband

is involved or other emergency circumstances. Johnson v. United States,

333 U.S. 10, 15 (1948) (dictum), suggests that searches may be justified

by the necessity o f an emergency, such as the threatened destruction of

evidence. Nor was this a search incident to a lawful arrest, United States

v. Rabinowitz, 339 U.S. 56 (1950).

3 In Johnson, a Seattle police detective, accompanied by federal nar

cotics agents, smelled burning opium and knocked at the door o f a hotel

room from which the odor emanated. A t the same time, the men an

nounced themselves as police officers. The door was opened, the only

occupant in the room was placed under arrest, and a search was made

which turned up incriminating opium and smoking apparatus which was

still warm, apparently from recent use. The district court refused to

suppress the evidence, the defendant was convicted and the conviction

affirmed by the Circuit Court of Appeals. This Court reversed (333 U.S.

at 15-17) :

The Government contends, however, that this search without war

rant must be held valid because incident to an arrest. This alleged

ground of validity requires examination of the facts to determine

whether the arrest itself was lawful. Since it was without a warrant,

it could be valid only if for a crime committed in the presence of the

arresting officer or for a felony o f which he had reasonable cause to

believe defendant guilty.

The Government, in effect, concedes that the arresting officer did

not have probable cause to arrest petitioner until he had entered her

1 2

son v. United States, 333 U.8. 10 (1948). “It goes without

saying that in determining the lawfulness of entry and the

existence of probable cause we may concern ourselves only

with what the officers had reason to believe at the time of

their entry.” Ker v. California, 374 U.S. 23 at 40 n. 11

(1963) (emphasis in original). The officers had no warrant

of arrest nor probable cause to believe a crime had been

committed; under no circumstances could their entry be

viewed as incident to efforts to make a lawful arrest.

The Arkansas Supreme Court did not deal with the rea

sonableness of the search but affirmed petitioners’ convic

tions on the ground that no matter how unreasonable, the

search did not violate petitioners’ constitutional rights be

cause Mrs. Dokes gave her consent to the officers’ entry.

This record, however, does not show waiver of Fourth

Amendment rights by Mrs. Dokes; much less that the state

met its burden of proving knowing and intentional waiver

of a constitutional right under the standards of Johnson

v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938).

This Court looks to the facts to determine if a constitu

tional waiver actually took place, BrooJchart v. Janis, 384

room and found her to be the sole occupant . . . Thus the Govern

ment quite properly stakes the right to arrest, not on the informer’s tip

and the smell the officers recognized before entry, but on the knowl

edge that she was alone in the room, gained only after, and wholly

by reason of, their entry o f her home. It was therefore their obser

vations inside of her quarters, after they had obtained admission

under color o f their police authority, on which they made their arrest.

Thus the Government is obliged to justify the arrest by the search

and at the same time to justify the search by the arrest. This will

not do. An officer gaining access to private living quarters under

color o f his office and o f the law which he personifies must then have

some valid basis in law for the intrusion. Any other rule would un

dermine “ the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses,

papers and effects,” and would obliterate one o f the most funda

mental distinctions between our form of government, where officers

are under the law, and the police-state where they are the law.

13

U.S. 1, 4 (1966) and the facts here show that the police

barged in without a thought to petitioners’ Fourth Amend

ment right to privacy. Sylvia Dokes testified that, one of

the officers told her to “ Take us back where you came from”

(R. 71) and that she did not invite the officers to her apart

ment (R. 71-72). Officer Terry corroborated Mrs. Dokes’

version because he acted as if Mrs. Dokes was in his cus

tody. He stated that “we stopped them and took them back

to the apartment” (R. 40) and that Mrs. Dokes raised no

objection to his entering only after he had identified him

self as a police officer outside the apartment (R. 41). Of

ficer Harris said it was “possible” that he stated “We are

police officers where is the party? . .. Take me to the party”

to Mrs. Dokes (R. 31). He also testified that after iden

tifying themselves as police officers they were “invited”

into the apartment but later clarified what he meant by

“ invited” :

“Q. And she then invited you in, or at least made

no objection to your coming in? A. She made no ob

jection to us coming in when we identified ourselves

as police officers” (R. 27).

More than forty years ago the Court refused to accept

this kind of “implied coercion” as waiver of Fourth Amend

ment rights, Amos v. United States, 255 U.S. 313, 317

(1924).

This evidence does not meet the state’s burden of show

ing a voluntary and understanding waiver of constitu

tional rights. Viewed in the light most favorable to the

state it shows only ignorant acquiescence in unlawful po

lice conduct because it is clear that petitioner Sylvia

Dokes was not told that the officers needed a warrant to

conduct a search or that the officers had no ground for

lawful entry absent waiver. While this Court has never

14

had occasion to confront the question squarely, Johnson v.

United States, 333 U.S. 10, 13 (1948) plainly takes the

view that in order to be effective, a consent to search or

seizure must be intentional relinquishment or abandon

ment of a known right or privilege. Cf. United States v.

Blalock, 255 F. Supp. 268 (E.D. Pa. 1966). This is the

concept of waiver ordinarily applicable to fundamental

guarantees and it has not been suggested the Fourth-

Fourteenth Amendment rights are exceptions to the rule.

See Johnson v. Zerhst, 304 U.S. 458, 464 (1938); Von

Moltke v. Gillies, 332 U.S. 708 (1948); Fay v. Noia, 372

U.S. 391, 439 (1963); Brookhart v. Janis, 384 U.S. 1, 5

(1966). It is not enough that the individual acquiesces in

a method of procedure against which the Constitution gives

protection; he or she must know of the protection which

the Constitution gives and intentionally abandon or re

linquish it. Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966).

Waiver of constitutional rights should not be found ex

cept on a record in which the state spells out fully and

convincingly the circumstances claimed to amount to the

waiver. See Swenson v. Bosler, 35 U.S.L. Week 3320

(March 13, 1967); Westbrook v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 150

(1966); Carnley v. Cochran, 369 U.S. 506, 513-517 (1962).

Petitioners submit that the only evidence of consent ap

pearing in this record, the inconsistent, incomplete, and

conclusory testimony of the arresting officers, fails to meet

the state’s heavy burden of proof, Johnson v. Zerhst, 304

U.S. 458 (1938) that a constitutional right has been waived.

15

II.

The Standards Under Which a State Meets its Burden

o f Showing a Waiver o f Fourth-Fourteenth Amend

ment Rights is a Question ©f Public Importance Which

Merits the Exercise o f This Court’s Certiorari Juris

diction,

A number of considerations make the question of waiver

raised a matter for the Court’s utmost concern.

First, as searches and seizures validated by consent

may proceed without a warrant or probable cause, or even

a showing of reasonableness, a finding of consent totally

precludes the operation of the Fourth Amendment. For

this reason the courts have long experienced systematic

abuse of the consent doctrine by unscrupulous police offi

cers. See e.g. United States v. Arrington, 215 F.2d 630,

637 (7th Cir. 1954); Lankford v. Schmidt, 240 F. Supp.

550, 557, 558 (D. Md. 1965) rev’d on other grounds, sub.

nom. Lankford v. Gelston, 364 F.2d 197 (4th Cir. 1966)

(series of 300 armed searches sought to be justified by

consent). The vigor of the Amendment depends on the

adoption of careful standards governing determination of

voluntary consent, Ker v. California, 374 U.S. 23, 33 (1963).

Secondly, the court has not decided a case involving the

voluntariness of consent to search and seizure in twenty

years and the few prior decisions do not address the

questions arising in case after case today.4 The Court’s

4 Gouled v. United States, 255 U.S. 298 (1921), where consent was

procured by misrepresentation, and Johnson v. United States, 333 U.S. 10

(1948), where entry “ was granted in submission to authority,” id. at 13,

have been viewed as extreme eases. United States v. Mitchell, 322 U.S.

65 (1944), considers only the effect o f the McNabb rule on consent to

search. McDonald v. United States, 335 U.S. 451 (1948), does not dis

tinctly address the question o f voluntariness of consent. But see Amos v.

United States, 255 U.S. 313, 317 (1924).

16

most extended discussion of the consent principle came in

the “public documents” cases, Davis v. United States, 328

U.S. 582 (1946); and Zap v. United States, 328 U.S. 624

(1946); and notwithstanding the admonition that “ [w]here

officers seek to inspect public documents at the place of

business where they are required to be kept, permissible

limits of persuasion are not so narrow as where private

papers are sought,” 5 lower courts have relied on Davis

and Zap in sustaining searches for entirely private items.6

Thirdly, concern with appropriate standards to ap

praise waiver is reflected in the frequent litigation of the

validity of consent to a warrantless search in the federal7

as well as the state8 courts. The critical role played by

5 Davis v. United States, 328 U.S. 582, 593 (1946).

6 See, e.g., Bees v. Peyton, 341 F.2d 859 (4th Cir. 1965), relying on

Zap.

7 In addition to the eases collected in the following pag'es, see these

recent federal circuit court decisions, e.g., Massachusetts v. Painten, 368

F.2d 142 (1st Cir. 1966); Bobbins v. MacKenzie, 364 F.2d 45 (1st Cir.

1966); United States v. Gorman, 355 F.2d 151 (2d Cir. 1965); Bivers v.

United States, 321 F.2d 704 (2d Cir. 1963); United States v. Smith,

308 F.2d 657 (2d Cir. 1962); United States v. Horton, 328 F.2d 132

(3d Cir. 1964); Beeves v. Warden, 346 F.2d 915 (4th Cir. 1965); Lands-

down v. United States, 348 F.2d 405 (5th Cir. 1965); Bobinson v. United

States, 325 F.2d 880 (5th Cir. 1964); Simmons v. Bomar, 349 F.2d 365

(6th Cir. 1965); United States v. Torres, 354 F.2d 633 (7th Cir. 1966);

United States v. Hilbrich, 341 F.2d 555 (7th Cir. 1965); Maxwell v.

Stephens, 348 F.2d 325 (8th Cir. 1965); Chapman v. United States,

346 F.2d 383 (9th Cir. 1965); Davis v. California, 341 F.2d 982 (9th

Cir. 1965); Frye v. United States, 315 F.2d 491 (9th Cir. 1963); Seed

v. Bhay, 323 F.2d 498 (9th Cir. 1963); Mosco v. United States, 301 F.2d

180 (9th Cir. 1962); Bogers v. United States, 369 F.2d 944 (10th Cir.

1966); Schultz v. United States, 351 F.2d 287 (10th Cir. 1965); McDonald

v. United States, 307 F.2d 272 (10th Cir. 1962); Villano v. United States,

310 F.2d 680 (10th Cir. 1962); Gatlin v. United States, 326 F,2d 666

(D.C. Cir. 1963).

8 See, e.g., the California cases collected in Note, 51 Calif. L. Rev. 1010

(1963); State v. Hanna, 150 Conn. 457, 191 A.2d 124 (1963); State v.

Scrotsky, 39 N.J. 410, 189 A.2d 23 (1963); Commonwealth v. Wright,

411 Pa. 81, 190 A.2d 709 (1963); Holt v. State, 17 Wis.2d 468, 117

N.W.2d 626 (1962).

17

waiver determinations is emphasized by recent decisions

of the Court stressing a defendant’s knowledge of his con

stitutional rights.9 Yet the absence of clear federal law

establishing standards for a finding of consent itself en

ables the “consent search” to undercut the protection af

forded individuals by the Fourth Amendment. See the

Appendix to Weinstein, Local Responsibility for Improve

ment of Search and Seizure Practices, 34 Rocky Mt. L.

Rev. 150, 176-179 (1962).

Finally, the decisions of lower courts are in conflict.10

All courts agree, of course, that consent must be “volun

tary” to be effective but differing results reflect differing

views on an unarticulated question of law: whether one

who does not know and is not told that officers cannot make

a search without a warrant should be held to -waive the

warrant requirement by acquiescing in a request to search.

We believe the invasion of privacy shown by this record

presents an appropriate occasion for the Court to address

itself to this critical question of federal law7.

9 E.g., Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966).

10 Compare Pelear v. United States, 315 F.2d 319 (5th Cir. 1963),

with United States v. Ziemer, 291 F.2d 100 (7th Cir. 1961). Compare

Higgins v. United States, 209 F.2d 819 (D.C. Cir. 1954) with United

States v. MacLeod, 207 F.2d 853 (7th Cir. 1953). Compare Peed v.

fihay, 323 F.2d 498 (9th Cir. 1963) with United States v. Evans, 194

F. Supp. 90 (D.D.C. 1961). Compare United States v. Haas, 106 F.

Supp. 295, 109 F. Supp. 433 (W.D. Pa. 1952) with United States v.

Minor, 117 F. Supp. 697 (E.D. Okla. 1953). Compare the inhospitality

toward a finding of consent by the Court of Appeals for the District of

Columbia Circuit, e.g., Judd v. United States, 190 F.2d 649, 651-652

(D.C. Cir. 1951), with the hospitality toward such a finding by the Court

o f Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, e.g., Martinez v. United States, 333

F.2d 405, 407 (9th Cir. 1964).

18

III.

Petitioners’ Convictions Are Unsupported by Any

Evidence in the Record.

Petitioners were convicted pursuant to Arkansas stat

utes which punish “any person who shall, by any act, cause,

encourage or contribute to” the delinquency of a child.11

The delinquent child is defined by Ark. Stats. Ann. §§45-204

as a person under eighteen years of age who:

(1) violates a law of this State;

(2) is incorrigible;

(3) knowingly associates with thieves;

(4) knowingly associates with vicious or immoral

persons;

(5) without cause or parental consent absents him

self from his home;

(6) is growing up in idleness or crime;

(7) knowingly frequents a house of ill-repute;

(8) knowingly frequents any policy shop;

(9) knowingly frequents any place where any gam

ing device is operated;

(10) patronizes, visits or frequents any saloon or

dram shop were intoxicating liquors are sold;

(11) patronizes or visits any public pool room where

the game of pool or billiards is carried on for

pay or hire;

(12) wanders about the streets in the nighttime with

out being on any lawful business or occupation;

11 See supra, pp. 3, 4.

19

(13) habitually wanders about any railroad yards or

tracks;

(14) jumps or attempts to jump on any moving* train;

(15) enters any car or engine without lawful author

ity;

(16) smokes cigarettes about any public place or

schoolhouse.

(17) is guilty of indecent, immoral or lascivious con

duct.

There are thus three elements of a contributory delin

quency charge: (1) an act by an adult, (2) whose effect is

to cause, encourage or contribute to (3) any of the kinds

of behavior which render a child under eighteen a delin

quent.

Although the state apparently proceeded on the theory

that petitioners contributed to the violation of Ark. Stats.

Ann. §48-903.1, supra, p. 4 (1964) a “ state law” incor

porated into the delinquency statutes by §§45-204 (1964),

the trial judge, over objection, charged the jury with all

17 kinds of delinquent behavior (R. 74, 75). Thus, we con

sider whether there was evidence of guilt under any of the

17 definitions.

Only clauses (1), (4), (5) and (17) are conceivably ap

plicable to the factual setting of this case. If, therefore,

the State failed to introduce any evidence that the peti

tioners acted in a manner so as to cause, encourage or

contribute to the performance of the acts enumerated in

those clauses by a person under eighteen years of age,

their convictions must be reversed, Thompson v. Louisville,

362'U.S. 199 (1960).

There is no evidence that petitioners caused, encouraged

or contributed to persons under eighteen behaving in an

2 0

“ indecent, immoral or lascivious” manner under clause

(17). There is certainly no suggestion in this record that

any of the occupants of petitioners’ apartment were be

having indecently or lasciviously. To the contrary, the po

lice officers testified that no one was rowdy or loud or

cursed or used obscene language.

There is no evidence in the record that petitioners

caused, encouraged or contributed to the absence from

their homes of any persons under eighteen years of age,

without the consent of their parents under clause (5). The

question of parental consent to be away from homes is

never raised by any of the testimony.

There is no evidence that petitioners caused, encouraged

or contributed to the association of persons under the age

of eighteen with “vicious or immoral persons” under

clause (4). None of the guests were so characterized.

Petitioners were responsible tenants of the Little Rock

Housing Authority and the record shows that petitioner

John Dokes and the other adults present were regularly

and legitimately employed.

Finally, petitioners submit that there is no evidence in

the record that they caused, encouraged or contributed to

violation of state law by a person under eighteen years of

age under clause (1). Although petitioners have never

been informed of the specific law in question and a written

charge has never been filed by the state, the theory upon

which the state apparently proceeded was that petitioners

were criminally responsible for a violation of Arkansas

liquor laws allegedly committed by persons under eighteen

who were uninvited guests in their apartment and to whom

they did not give alcohol. Ark. Stats. Ann. §48-903.1,

supra, p. 4, makes it a misdemeanor for any person un

2 1

der 21 to possess intoxicating liquor, wine or beer.12 How

ever, the evidence fails to reveal that the Hokes’

caused, encouraged or contributed to the possession of

liquor, wine, or beer by any one under 18 (the age ceiling

of the delinquency statute). There is, simply, evidence

that there were beer cans and a few mixed drinks in peti

tioners’ apartment on the night in question. The officers

testified that while questioning some of the minors they

noticed the odor of alcohol on their breaths, but only one

of these minors was identified as being under eighteen

years of age as required by the delinquency statute (Com

pare E. 50 with E. 53) and the officers did not see the

Hokes’ or anyone else give a minor a drink.13 Most signifi

cantly, petitioners’ testimony that both the beer and liquor

were brought to the apartment by adult guests, and that

they, petitioners, gave no alcoholic beverage to any minor,

was not contradicted or rebutted. Indeed, it was corrobo

rated by a member of Hokes’ singing group (E. 82).

There is no evidence that petitioners caused, encouraged

or contributed to the unlawful possession of alcoholic bev

erages within their apartment; merely testimony that an ad

mittedly uninvited guest under eighteen had an odor of al

cohol on her breath. This was the trial court’s view of

the case. Although the jury was charged that the State

had the burden of proving petitioner’s guilt beyond a rea

sonable doubt (E. 76), the court denied a motion to direct

a verdict in favor of petitioners and stated: “I think they

12 It should be noted that §48-903.1 also makes purchasing alcoholic

beverages for a minor a misdemeanor but this offense could not con

ceivably be the basis o f petitioners’ conviction. They were charged

with contributing to the violation o f a state law by a minor and the pur

chasing offense cannot be committed by a minor.

13 There is likewise testimony that a minor possessed an aleoholic

beverage but not that a person under eighteen (as required by the delin

quency statute) performed this act.

2 2

have to make some explanation for the party, being it took

place in their apartment. They were responsible for it.”

And the court directed a verdict of acquittal in favor of

two adult co-defendants because the party did not take

place in their home (R. 57). Petitioners may not be found

criminally responsible, however, for causing, encouraging

or contributing to delinquency solely because the “delin

quency” took place in their home.

This case is controlled by the reasoning of Schware v.

Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U.S. 232 (1957), a case relied

upon to support the holding in Thompson v. Louisville,

supra. See 362 U.S. 206 n. 13 (1960). At issue was a find

ing that petitioner did not have a good moral character.

Although he introduced uncontradicted evidence of good

character, the Bar Examiners relied upon the facts that

(1) petitioner had in the past used aliases, (2) he had been

arrested on at least two occasions, but never tried or con

victed, (3) he had at one time been a member of the Com

munist Party, to support its finding that Schware lacked

the requisite character to become a member of the New

Mexico bar. Mr. Justice Black, for the court, found that

there was “no evidence in the record which rationally jus

tifies a finding that Schware was morally unfit to practice

law” (353 U.S. at 246-47). In a concurring opinion, Mr.

Justice Frankfurter expanded upon the majority’s rationale

(353 U.S. at 251):

This brings me to the inference that the [New Mexico]

court drew . . . To hold as the court did . . . is so

dogmatic an inference as to be wholly unwarranted.

. . . But facts of history that we would be arbitrary in

rejecting bar the presumption, let alone an irrebuttable

presumption, that response to foolish, baseless hopes

regarding the betterment of society made those who

had entertained them but who later undoubtedly came

23

to their senses and their sense of responsibility “ques

tionable characters.” Since the Supreme Court of

New Mexico as a matter of law took a contrary view

of such a situation in denying petitioner’s application,

it denied him due process of law.

Here as in Schware, the “inference” is “unwarranted” .

Because of a smell of alcohol on the breath of one person

under eighteen in their apartment petitioners did not cause,

encourage or contribute to the minor’s possession of alco

hol, a violation of state law which amounts under this

statute to juvenile delinquency.

IV.

Petitioners Were Convicted Under a Contributory

Delinquency Statute So Sweeping and Vague as to Deny

Them Due Process of Law Guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment.

Petitioners’ conduct was criminal nnder the following-

standard of §45-239 Ark. Stats Ann.:

Any person who shall, by any act, cause, encourage or

contribute to the dependency or delinquency of a child

as these terms with reference to children are defined

by this act or who shall for any cause, be responsible

therefor . . . (italics supplied).

The italicized terms denominate the degree of influence

upon the conduct of a child under eighteen which an adult

must exert in order to be guilty of contributory delin

quency. The definition of delinquency incorporated in the

statute refers to 17 forms of delinquency enumerated in

§45-204, supra, p. 3, which define a delinquent child as one

who is, inter alia, “growing up in idleness” , who “ smokes

24

cigarettes about any public place or about any school-

house” , who “associates with vicious or immoral persons” ,

who is “guilty of . . . immoral . . . conduct” or who “violates

a law of this State” .

The Supreme Court of Arkansas, in response to peti

tioners’ claim that the record revealed no evidence of

guilt, construed §45-239 expansively, holding that “it is

only necessary for the state to prove a condition or cir

cumstances existing that would tend to cause, encourage

or contribute to the delinquency of a child” infra, p. 4a.

In short, the indicia of delinquency incorporated in the

contributory delinquency statute need not be shown to

have actually occurred; merely conditions or circum

stances tending to establish them are necessary. At the

same time the Supreme Court of Arkansas did not define,

but merely reasserted, the statutory words “cause, en

courage or contribute to.”

Such statutes have potential for grave conflict with fed

eral freedoms. This is because the First Amendment

protects freedom of association, and the heart of any

contributory-delinquency statute is regulation of the as

sociation of adults and children. These statutes do not

punish simply aiding-and-abetting criminal conduct by a

child; they punish the sort of relationship between the

adult and the child which is likely, in the State’s view, to

have ill effects on the child. Arkansas’ focus on the

maintenance of a “ condition” or “circumstances” high

lights the problem. The “ condition” and “circumstances”

spoken of here are incidents of an associative relationship.

When the State seeks to regulate those incidents, and to

prescribe the conditions and circumstances under which

individuals will be permitted to associate, it touches very

close to the core of the First Amendment. Here, the strict

standards of permissible statutory vagueness apply.

25

NAACP v. Button, 371 IT.S. 415, 432 (1963); Ashton v.

Kentucky, 384 IT.S. 195 (1966); DombrowsU v. Pfister,

380 U.S. 479 (1965).

Because the Arkansas statutes are in many respects

typical this case presents an appropriate occasion for

consideration of whether catchall delinquency statutes are

sufficiently certain to withstand the close scrutiny required

by the Constitution, even though §§45-204, 239 themselves

have been amended.14 Compare Spencer v. Texas, 385 TJ.S.

554, 556, Note 2 (1967).

14 The statutes now read as follow s:

§45-239. Persons contributing to delinquency. Any person who shall

cause, aid, or encourage any person under eighteen (18) years of age to

do or perform any act which if done or performed would make such

person under eighteen (18) years of age a “ delinquent child” as that

term is defined herein, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor. Provided that

when any person is charged by indictment or information with a viola

tion of this Act, such indictment or information shall state the specific

act with which the defendant is charged to have committed in violation

of this Act. Any person convicted of a violation of this section shall be

punished by imprisonment for not less than sixty (60) days nor more

than one (1) year, and by a fine of not less than one hundred dollars

($100.00) nor more than five hundred dollars ($500.00). Provided, the

court may suspend or postpone enforcement of all or any part of the

sentence or fine levied under this section if in the judgment of the court

such suspension or postponement is in the best interest o f any dependent,

neglected or delinquent child as these terms are defined in this act.

§45-204. Delinquent child. The term “ delinquent child” shall mean and

include any person under eighteen (18) years of age:

(a) Who does any act which, if done by a person eighteen (18) years

o f age or older, would render such person subject to prosecution for a

felony or a misdemeanor;

(b) Who has deserted his or her home without good or sufficient cause

or who habitually absents himself or herself from his or her home without

the consent o f his or her parent, step-parent, foster parent, guardian, or

other lawful custodian;

(c) Who, being required by law to attend school, habitually absents

himself or herself therefrom; or

(d) Who is habitually disobedient to the reasonable and lawful com

mands of his or her parent, step-parent, foster parent, guardian or other

lawful custodian.

Any reputable person may initiate proceedings against a person under

eighteen (18) years of age under this Act by filing a petition therefor

2 6

These laws “condemn” an “extraordinarily wide range

of adult behavior . . . ” Geis, Contributing to Delinquency,

8 St. Louis U.L.J. 59, 75 (1963) and they have been

sharply criticized.15 16 The delinquency statutes under which

petitioners were convicted are representative of state

criminal legislation in this area and the constitutional de

fects from which they suffer are common to nearly all

state laws on this subject. All fifty states and the District

of Columbia have created the crime of contributory de

linquency, the statutes typically include “any person” or

“any other person” whom the court finds has contributed

to the delinquency of a child, no matter how slight the

contact between adult and minor. Nearly all States pro

hibit acts which “ encourage or contribute to delinquency,”

adding, variously, “aid,” “tend to cause,” “ cause,” “pro

mote,” “produce,” etc.16 Thus, for example, the Colorado

law provides:

with the juvenile court. All such proceedings shall be on behalf of the

State and in the interest o f the child and the State and due regard shall

be given to the rights and duties of parents and others, and any person

so proceeded against shall be dealt with, protected or cared for by the

county court as a ward o f the State in the manner hereinafter provided.

15 See Geis, ibid; Ludwig, Delinquent Parents and the Criminal Law,

5 Vand. L. Rev. 719 (1952); cf. Ludwig, Youth & the Law (1955);

Gladstone, The Legal Responsibility of Parents for Juvenile Delinquency

in New York, 21 Brooklyn L. Rev. 172, 180 (1955); Rubin, Are Parents

Responsible for Juvenile Delinquencyf in Crime & Delinquency 35 (2d

ed. 1961) ; Rubin, Should Parents Be Held Responsible for Juvenile

Delinquency?, 34 Focus 35 (March 1955). The Standard Juvenile Court

Act specifically omits any law of contributory delinquency, 5 N.P.P.A.J.

323, 346 (1959); the Model Penal Code reserves its sanctions for parents

alone, and then only for gross breaches of responsibility. Model Penal

Code §230.4, p. 192 (P.O.D. 1962) commentary to §207-13, p. 183 (Tent,

draft No. 9, 1959).

16 Ala. Code Ann. Tit. 13 §366 (Recomp. 1958); Alaska Stat. Ann.

§11.40.130 (1962); Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. §13-822 (1956); Cal. Penal

Code (West) §272 (Supp. 1966); Colo. Rev. Stat. §22-7-1 (1963); Conn.

Gen. Stat. Ann. §53-254 (1958); D.C. Code Enc. §16-2314(b) (1966);

Fla. Stat. Ann. §828.21 (1965); Ga. Code Ann. §§24-9904, 26-6802

27

Any person who shall encourage, cause or contrib

ute to the dependency, neglect, or delinquency of a

child or shall do any act to directly produce, promote

or contribute to the conditions which render such a

child a dependent, neglected or delinquent child. . . ,17

Although a very few contributory delinquency statutes

are self-contained, and include a listing of the qualities

which render a child delinquent (and thus subject an adult

to punishment),18 the vast majority of statutes make im

plicit or explicit reference to other state laws to provide

the definition of “delinquent child” or “delinquency.”

Parallels exist between the statutes under which peti-

(Repl. 1959); Hawaii Rev. Laws §330-6 (1955); Idaho Code §16-1817

(Supp. 1965); 111. Stat. Ann. (Smith-Hurd) ch. 23 §2361a (Supp. 1966);

Ind. Stat. Ann. (Bums) §9-2804 (Repl. 1956); Iowa Code Ann. §233.1

(1949); Kan. Stat. Ann. §38-S30(a) (1964); Ky. Rev. Stat. §208.020

(3) (a) (1958); La. Rev. Stat. Ann. (West) Tit. 14 §92.1(A) (Supp.

1966); Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. Tit. 17 §859 (1964); Md. Code Ann. Art.

26 §§53(c), 7 6 (f), 79 (Repl. 1966); Mass. Ann. Laws ch. 119 §63 (Supp.

1965); Mich. Stat. Ann. §28.340 (Repl. 1962); Minn. Stat. Ann. §260.315

(Supp. 1966); Mo. Stat. Ann. §559.360 (Supp. 1966); Mont. Rev. Codes

Ann. §10-617 (Supp. 1965); Neb. Rev. Stat, §28-477 (Supp. 1965);

Nev. Rev. Stat. §201.110 (1965); N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. ch. 169 §32

(Supp. 1965); N.J. Stat. Ann. §2A:96-4 (1953); N.M. Stat. Ann.

§40A-6-3 (Repl. 1964); N.Y. Penal Law §494; N.C. Gen. Stat. Ann.

§110-39 (Repl. 1966); N.D. Century Code Ann. §14-10-06 (Repl. 1960);

Ohio Rev. Code Ann. §2151.41 (1953); Okla. Stat. Ann. Tit. 21 §856

(1958); Ore. Rev. Stat. §167.210 (Repl. 1965); R.I. Gen. Laws §11-9-4

(1956); S.C. Code Ann. §16-555.1 (1962); S.D. Code §43.0409 (1939);

Tenn. Code Ann. §37-270 (Supp. 1966); Tex. Penal Code (Vernon)

Art. 534a (Supp. 1966); Utah Code Ann. §55-10-80(1) (Supp. 1965);

Vt. Stat. Ann. Tit. 13 §1301 (1958); Va. Code Ann, §18.1-14 (Repl.

1960); Wash. Rev. Code Ann. §13.04.170 (1962); W. Va. Code Ann.

§49-7-7 (1966); Wis. Stat. Ann. §48.45(4) (a) (1957); WTyo. Stat. §§14-7,

14-23(a) (Repl. 1965).

17 Colo. Rev. Stat. §22-7-1 (1963).

l s E.g., Iowa Code Ann. §233.1 (1949); La. Rev. Stat. Ann. (West)

Tit. 14 §92.1 (Supp. 1966); Mont. Rev. Codes Ann. §10-617 (Supp.

1965); S.C. Code Ann. §16-555.1 (1962); Vt. Stat. Ann. Tit. 13 §1301

(1958).

2 8

tioners were convicted and many other state definitional

statutes.19 Especially prominent are the recurrent pro

hibitions against association with “vicious or immoral per

sons,” or “growing up in idleness or crime.” 20 21

Although not all legislatures have defined delinquency in

such broad terms,31 most contributory delinquency laws

share the vice of unclear denomination of the acts which

are sought to be proscribed. Consistent with the view of

the Arkansas Supreme Court most state laws do not re

quire a minor to have been made a delinquent in order for

an adult to have contributed to his delinquency.22 Such

terms are employed as “ tends to cause,” Nev. Eev. Stat.

§201.110 (1965); “encourages,” Minn. Stat. Anno. §260.27

(1959); “contribute to the conditions,” Colo. Eev. Stat.

§22-7-1 (1963); and “responsible for . . . conditions which

19 See, e.g., Alaska Stat. Ann. §11.40.150 (1962); Fla. Stat. Ann.

§39.01(11) (1961); Ind. Stat. Ann. (Burns) §9-2803 (Eepl. 1956); Md.

Code Ann. Art. 26 §§52(e), 78(b) (Eepl. 1966); Mont. Eev. Codes Ann.

§10-617 (Supp. 1965); Okla. Stat. Ann. Tit. 21 §857 (1958); S.C. Code

Ann. §16-555.1 (1962); S.D. Code §43.0301 (1939); Tenn. Code Ann.

§37-242 (Supp. 1966).

20 Ibid.

21 Examples o f narrower definition include Del. Code Ann. Tit. 10

§§901, 1101 (1953); 111. Stat. Ann. (Smith-Hurd) eh. 23 §2360(a) (Supp.

1966); Mass. Ann. Laws eh. 119 §52 (Supp. 1965); Neb. Eev. Stat.

§43-201 (Supp. 1965); Wash Eev. Code Ann. §1304.010 (1962).

22 E.g., Smithson v. State, 34 Ala. App. 343, 39 So.2d 678 (1950);

Anderson v. State, Sup. Ct. Op. #156 (File 271); 384 P.2d 669 (Alaska

1963); Ariz. Eev. Stat, §13-823 (1956), see State v. Locks, 94 Ariz. 134,

382 P.2d 241 (1963); People v. Calkins, 48 Cal. App. 2d 33, 119 P.2d 142

(1941); Del. Code Ann. Tit, 11 §431 (a) (3) (Supp. 1964); State v.

Drury, 25 Idaho 787, 139 Pac. 1129 (1914); La. Eev. Stat. Ann. (West)

Tit. 14 §92.1 (A ) (Supp. 1966); Me. Eev. Stat. Ann. Tit. 17 §860 (1964);

Mich. Stat. Ann. §28.340 (Eepl. 1962); State v. Johnson, 145 S.W.2d

468 (Mo. App. 1940); People v. Dritz, 259 App. Div. 210, 18 N.Y.S.2d

455 (1940); State v. Griffin, 93 Ohio App. 299, 106 N.E.2d 668 (1952);

TV allin v. State, 84 Okla. Cr. 194, 182 P.2d 788 (1947); Commonwealth

v. Jordon, 136 Pa, Super. 242, 7 A.2d 523 (1939); S.D. Code §43.0409

(1939); Lavvorn v. State, 389 S.W.2d 252 (Tenn. 1965); W. Va. Code

Ann. §49-7-8 (1966); Wis. Stat. Ann. §48.45(5) (1957).

2 9

may cause,” Conn. Gen. Stat. Anno. §53-254 (1960). Fur

thermore, under many state laws, including Ark. Stat,

Ann. §45-239, a defendant may be convicted without having

intended to affect the juvenile in any way.23

The Arkansas statutes do not as written, or as supple

mented by the interpretations of the Supreme Court of

Arkansas, provide an ascertainable standard of crim

inality or guilt. The definition of the actions which may

be punished is so broad that it is effectively relegated

to the police, and ultimately to the courts, for ad hoc de

termination after the fact in every case. As the facts of

this case clearly demonstrate this vague statute is subject

to “ sweeping* and improper application,” NAACP v. But

ton, 371 U.S. 415, 433 (1963) by the police to harass the in

nocent participants in an orderly, but unpopular, inter

racial social gathering.24 Where, as here, a constitutional

23 While some statutes include modifiers such as “knowingly or wil

fully,” N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. eh. 169 §32 (Supp. 1965), others, e.g'., Me.

Rev. Stat. Ann. Tit. 17 §859 (1964) do not. In some instances, the re

quirement o f scienter has been very specifically read out of the statute.

See Anderson v. State, Sup. Ct. Op. #156 (File 271), 384 P.2d 669

(Alaska 1963). It must be emphasized that juvenile and contributory

delinquency are not common law crimes presumed to attain a certain

specificity, but entirely the product o f statute. Of. Champlin Ref. Co. v.

Corporation Comm’n, 286 U.S. 210, 242-43 (1942).

24 These statutes permit arbitrary disposition o f adults who are in

volved along with young people in unpopular social movements. Juveniles,

for example, have comprised a large proportion o f those who in the past

decade have peacefully demonstrated for their civil rights and have been

unlawfully arrested for asserting constitutionally protected rights. The

treatment accorded these minor Negroes demonstrates the capacity to

punish for reasons totally unrelated to individual welfare of the child.

In one of the few studies of the subject, the United States Civil Rights

Commission concluded that “ . . . local authorities used the broad defini

tion afforded them by the absence o f safeguards [in juvenile proceedings]

to impose excessively harsh treatment on juveniles.” U. S. Comm’n on

Civil Rights Report, Law Enforcement, 1965, pp. 80-83.

The place the Commission studied was Americus, Georgia where:

“Approximately 125 juveniles were arrested during the Americus

demonstrations, and their cases disposed of in a unique manner. Some

3 0

right to privacy is involved, the principle that penal laws

may not be vague must, if anything, be enforced even more

stringently. Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965).

The court below held that “it is only necessary for the

state to prove a condition or circumstance existing that

would tend to cause, encourage or contribute to the delin

quency of a child.” Thus the words “cause, encourage or

contribute to” found in the statute are left unrestricted.

The chance that “the ordinary person can intelligently

o f them were released from jail upon payment o f a jail fee o f $23.50,

pins $2 per day for food. These fees were paid by parents who

agreed to send their children to relatives living in the country. No

court hearing was held in these cases; o f those juveniles who ap

peared in court (approximately 75% o f those arrested) about 50

were sentenced to the State Juvenile Detention Home and placed

on probation on the condition that they would not associate with

certain leaders of civil rights organizations in Americus.

“ Many juveniles arrested in Americus were detained for long

periods o f time without bail or hearing. The juvenile court judge