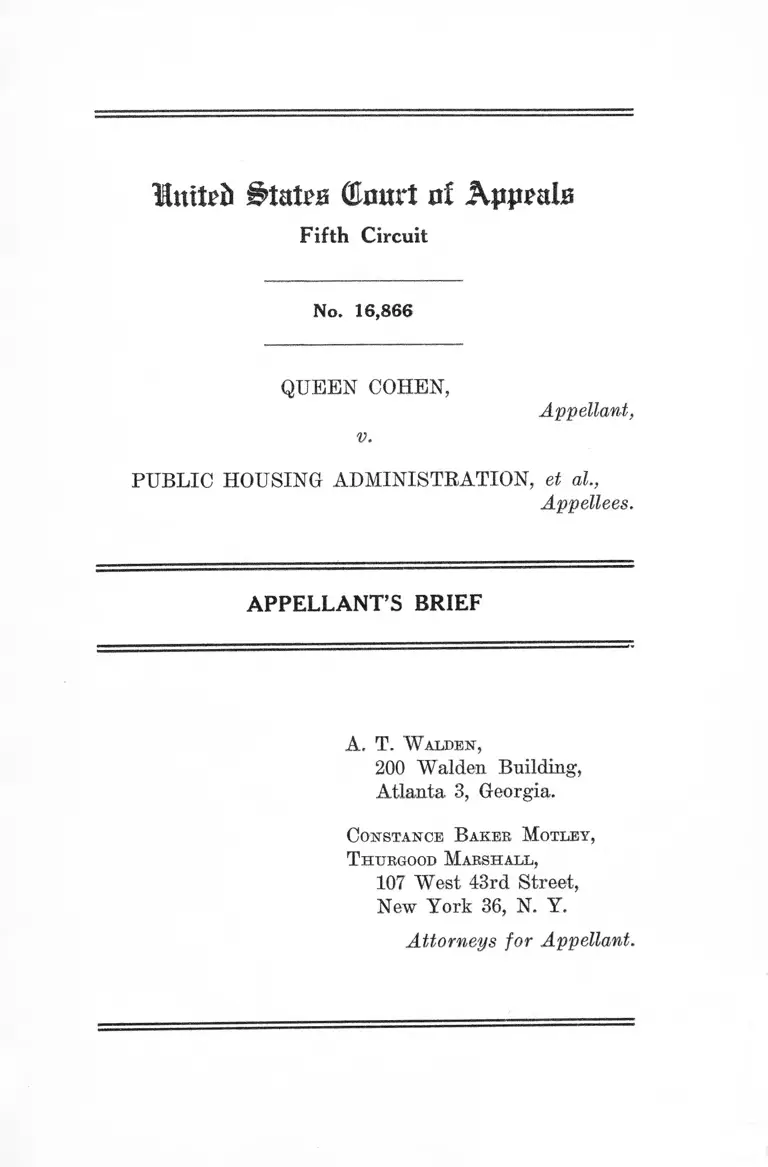

Cohen v. Public Housing Administration Appellant's Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Cohen v. Public Housing Administration Appellant's Brief, 1957. 27a62ce1-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/428185f5-3f0f-494d-8d15-7b41ef0a6150/cohen-v-public-housing-administration-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

United States (Emtrt of Appeals

Fifth Circuit

No. 16,866

QUEEN COHEN,

v.

Appellant,

PUBLIC HOUSING ADMINISTRATION, et ah,

Appellees.

APPELLANTS BRIEF

A. T. W alden,

200 Walden Building,

Atlanta 3, Georgia.

Constance B aker Motley,

T htjrgood Marshall,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York 36, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellant.

Inttffi States (£mtrl nf Appeals

Fifth Circuit

No. 16,866

-------------o-------------

Q ueen C o h e n ,

v.

Appellant,

P u blic H ousing A d m in istra tio n , et al.,

Appellees.

.................... .................... o — — _ _ _ _ _ _

APPELLANT’S BRIEF

Statement of the Case

This case involves governmentally enforced racial

segregation in public housing in Savannah, Georgia.

The present appeal is from an order of the United

States District Court for the Southern District of Georgia,

Savannah Division, dismissing appellant’s cause of action

after a full trial on the merits on the grounds that 1) the evi

dence failed to- establish that appellant had made applica

tion for admission to any public housing project and 2)

the undisputed testimony shows that appellant was not

entitled to a statutory preference for admission under

Title 42, United States Code, § 1410(g) or § 1415(8)(c).

Heyward, et al. v. Public Housing Administration, et al,

154 F. Supp- 589.

Before the trial on the merits, appellant was one of

several original plaintiffs who took a prior appeal to this

court from orders of the court below dismissing the com

plaint herein. Heyward, et al. v. Public Housing Adminis

tration, et al, 238 F. 2d 689 (1956), rev’g 135 F. Supp. 217.

2

Just prior to commencement of trial, all of the other

named plaintiffs voluntarily withdrew as plaintiffs and

the action was maintained by this appellant on behalf of

herself and others similarly situated (R. 7, 40-42).

From the entire record in this case, the following facts

appear:

1. The housing program involved in this case is low

rent public housing provided for by the United States

Housing Act of 1937, as amended,1 (PHA Exhibit 1). This

is a program whereby the federal government, through the

Public Housing Administration, and local public housing-

agencies established by law in the several states, enter into

contracts for the construction, operation and maintenance

of decent, safe and sanitary dwellings (PHA Exhibit 1).

These dwellings are available to only those families who,

because of their low incomes, are unable to secure decent,

safe and sanitary private housing at the lowest rates at

which such private housing is being provided in the locality

(R. 85).

2. The Public Housing Administration, hereinafter

referred to as PHA, and the Housing Authority of Savan

nah, Georgia, hereinafter referred to as SHA, have entered

into contracts for construction, operation and maintenance

of such public housing projects in the City of Savannah

(PHA Exhibit 1).

3. PHA does not enter into contracts with local hous

ing agencies in the absence of a demonstrated need for such

housing in the locality concerned (R. 85). The present

need for low rent public housing in Savannah has been

determined by a survey of the total volume of decent, safe

and sanitary dwellings available to families of low income.

This survey was made by SHA in connection with its plans

for construction of a new 337 unit project for Negro oc

1 Title 42, United States Code, § 1401, et seq.

3

cupancy. This survey concludes that there is no decent,

safe and sanitary rental housing available in Savannah

for families who qualify for low rent public housing and

that the only sales housing available for such families is

reported to be selling between $6,000 and $7,000, but the

majority of such housing is selling at prices in excess of

$7,000 (R. 110-112, Plaintiff’s Exhibits 7 and 8).

4. In Savannah, persons eligible for low rent public

housing by virtue of their low incomes are as follows:

a) Two person families, maximum income limit

$2,500.

b) Three or four person families, maximum income

limit $2,700.

c) Five or more person families, maximum income

limit $2,900.

d) Maximum income allowed for continued occu

pancy after admission, $3,200 (Plaintiff’s Ex

hibit 10, Answers to Interrogatory No. 6, R. 83).

These maximum income limits and the rent schedules

applicable to public housing in Savannah have been deter

mined by SHA and approved by PHA (R. 67, 79).

5. In the development of public housing projects in

Savannah, SHA applies to PHA for preliminary loans for

the purpose of making surveys to determine the need, for

the purpose of developing plans for the projects, and for

the purpose of paying cost of construction of projects.

SHA’s bonds are subsequently sold to the public and the

federal government, through PH A’s contracts with SHA,

has guaranteed repayment of these bonds. PHA has also

agreed to contribute, when necessary, a cash subsidy in an

amount up to four per cent of the total shelter rents of all

projects to assist in amortization and payment of interest

upon such bonds. Preliminary loans for surveys, plans

4

and construction are made directly by PHA to SHA and

bonds of SHA are not sold until after such preliminary

loans have been made (R. 56, 70-71, 169).

6. PHA has a regional office in Atlanta, Georgia

(R. 48). This office actually executes the contracts in

volved in this case with SHA (R. 49-50). The following

functions are performed by the regional office in Savannah:

Annual audit of books of SHA, review of the admissions

of tenants and calculations of rent by SHA, review of

SHA’s budget, approval of all sites selected by SHA

(R. 51-52). All plans and specifications for public housing

projects are subject to approval by PHA (R. 74). During

construction of each project, a project engineer on the

staff of PHA Regional Office in Atlanta is stationed in

Savannah for the purpose of determining whether the con

struction is proceeding in accord with plans and specifica

tions approved by PHA (R. 74). PHA also conducted its

own survey in Savannah to determine the present need in

that city for public housing (R. 84). PH A’s regional office

also has a staff member whose primary function is to con

sider and approve the treatment afforded Negro families

(R. 57).

7. In case of any substantial default with respect to

the terms and conditions of the contracts between PHA

and SHA, PHA has the power to take over and operate

the project with respect to which the default occurs

(R. 71-73).

8. The first public housing units in Savannah opened

for occupancy in 1940 (R. 115). Six projects have been

constructed since that date under the provisions of the

United States Housing Act of 1937, as amended (R. 81).

Two former defense public housing projects previously

owned by PHA have been transferred to SHA for use as

low rent public housing projects and are now operated the

same as the other six projects (R. 68, 79). SHA has agreed

to pay the net proceeds of the rents collected from these

5

projects to PHA for the next 40 years (R. 69). A project

is presently under construction (R. 81). When this project

is completed, there will be a total of nine public housing

projects in Savannah (R. 81), A tenth public housing-

project consisting of 800 units is in the planning stage

(R. 86).

Of the six projects already built under the United

States Housing Act of 1937, as amended, three, Fellwood

Homes, Fellwood Annex, and Yamacraw Village, are

occupied by Negro families. Three are occupied by white

families (R. 81-82). The two former defense housing

projects were occupied by white families, only, when owned

by PHA and are still occupied by white families only

(R. 68). The project presently under construction and

the proposed 800 unit project are planned for Negro occu

pancy (R. 93).

9. Limitation of certain projects to Negro occupancy

and the limitation of others to white occupancy is approved

by PHA through approval of SHA’s Development Pro

grams which must reflect application of PH A’s racial

equity requirement (R. 54-55).2 PHA, by its adminis

trative rules and regulations, requires that a local pro

gram “ reflect equitable provision for eligible families of

all races determined on the approximate volume of their

respective needs for such housing” (Plaintiff’s Exhibit 2,

PHA Racial Policy). The need of the two races is de

termined primarily by the approximate volume of sub

standard housing* occupied by each race (R. 91-92).

Application of this formula resulted in the present deter

mination that equitable provision for Negro families in

Savannah requires that they be provided with approx

imately 75% of the total number of family units and that

equitable provision for white families requires that they

be provided with approximately 25% of the total number

2 The two most recent Development Programs were sent up to

this court in their original form. Plaintiff’s Exhibits 7 and 8.

6

of family units (R. 106-107). However, N egroes presently

occupy only 42.7% of the existing units and whites, be

cause of the addition of the two former defense housing

projects to the public housing supply, presently occupy

57.3% of the existing units (R. 104). The Development

Programs when approved by PHA become a part of the

contracts between PHA and SHA (R. 53-178). Once a

determination is made as to the approximate per cent of

the total number of units to be occupied by Negro f a milies

and the per cent of units to be occupied by white f amilies,

PHA would object to a deviation from these percentages

by SHA (R. 181).

10. The need for public housing among’ Negro families

in Savannah has always been disproportionately greater

than the need among white families (R. 86-87).

11. The most recently completed project in Savannah

is Fred Wessels Homes which opened for occupancy in

1954 (R. 188). This project has been built on a site located

approximately seven blocks from the main business area

1 of Savannah (R. 114). It contains 250 family units at a cost

! of approximately $2,800,000 (R. 113). Prior to construction

S of this project, the site was occupied by 250 Negro families

f an-d 70 white families (R. 102-103). This project has been

: limited to white occupancy (R. 103).

12. Sixty-nine Negro families eligible for public hous

ing who were displaced from the site of Fred Wessels

Homes and who made application to SHA for relocation,

were relocated in Fellwood Homes Annex, a project con

taining 127 units, which was completed prior to Fred

Wessels Homes for the purpose of housing Negro families

displaced from the Fred Wessels site (R. 88, 89). Seven

teen displaced Negro families were housed in Yamacraw

Village, an older Negro project (R. 89).

13. Fourteen of the original eighteen plaintiffs in this

case were former occupants of the site of Fred Wessels

Homes. These fourteen original plaintiffs were among

those relocated in Fellwood Homes Annex (R. 125).

14. As of December 23, 1955 no white families living

in Fred Wessels Homes were families displaced by any

public low rent or slum clearance projects (Plaintiff’s

Exhibit 10, Answer to Interrogatory No, 8).

15. Appellant, Queen Cohen, was not a former resident

of the Fred Wessels site. She was a resident of a site

across the street from the Fred Wessels site. She was

displaced from her home when a commercial enterprise

which had been located on the site of Fred Wessels Homes

moved its business to the site of appellant’s former resi

dence (R. 204-205). When appellant received a thirty day

notice from her landlord to vacate, she went to the office

of SHA which is located in the Fred Wessels Homes, for

the purpose of making application for a family unit

(R. 131). She was advised by a white male employee that

the Fred Wessels project was not for Negro families

(R. 133). She was not permitted to make a formal applica

tion (R. 133). At that time the buildings were completed

but unoccupied (R. 135).' Appellant desires to live in Fred

Wessels Homes (R. 139). She is the mother of four chil

dren, one of whom is in the armed services of the United

States (R. 133). Her husband is employed and earns fifty

dollars per week (R. 206).

16. Part II, Section 209 of the Annual Contributions

Contract between PHA and SHA provides that service

men and families of servicemen are to be given preference

for admission and as among such servicemen preference

is given to displaced families, i. e., families displaced by a

public housing project or public slum clearance project8

(Plaintiff’s Exhibit 1). Subject to the preferences estab

lished by Section 209, priority with respect to admission

is also given to families having the greatest urgency of 3

3 This proyision is based upon the requirements of Title 42,

United States Code § 1410(g).

8

need by the provisions of Section 208 of said contract.4

PHA has the responsibility of seeing that these prefer

ences are applied (R. 175). However, because of the

racially segregated projects in Savannah, these priorities

operate with respect to Negro applicants only as to those

projects limited to Negro occupancy and as to white

families only with respect to those projects limited to white

occupancy (R. 172).

17. The evidence shows that other Negroes also went

into the office located in Fred Wessels Homes to apply for

housing. Those who did so were housed in Fellwood

Homes. None was considered for admission, or permitted

to apply for admission, to Fred Wessels Homes (R. 95-97).

18. Prior to the opening of Fred Wessels Homes for

occupancy, SHA publicly announced that this project

would be for white occupancy (R. 112).

19. The manager of Fred Wessels Homes who took

applications understood that the project was limited to

white occupancy (R. 201).

20. Applicants for public housing in Savannah make

application for housing but may state a preference for

admission to a particular project. However, the ultimate

determination as to the project in which the applicant

family will reside remains with SHA (R. 96-97).

21. \ The public housing program in Savannah is a

long range program which is not yet completed and it

appears that in the future preliminary loans for the con

struction of other racially segregated projects will be made

by PHA to SHA and that the amount of these funds will

be well in excess of $3,000. (R. 93, 71).

22. Section 206 of the Annual Contributions contract

provides that citizen families of servicemen are eligible

4 This provision is based upon the requirements of Title 42,

United States Code § 1415(8) (c ) .

9

for admission if they are regularly living together as a,

family of two or more persons related by blood, marriage,

or adoption and if their net income, less an exemption to

be established by the local authority not in excess of $100

for each minor member of the family other than the head

of the family and his spouse, does not exceed the applicable

income limit for admission established by the local au

thority and approved by PHA.5

Specification of Errors

1. The trial court erred in dismissing appellant’s suit,

after a full trial on the merits, on the ground that appel

lant failed to prove that she had ever made application

for admission to Fred Wessels Homes.

2. The trial court erred in finding and concluding that

appellant was not entitled to any preferential rights of

admission under the United States Housing Act of 1937,

as amended.

3. The trial court erred in refusing to grant the relief

to which appellant is entitled.

0 Title 42, United States Code § 1402(14) provides that, “ The

term ‘serviceman’ shall mean a person in the active military or naval

service of the United States who has served therein at any time * * *

(iii) on or after June 27, 1950, and prior to such date thereafter as

shall be determined by the President.”

10

ARGUMENT

I. The Court Below Erred In Ruling That Appel

lant’s Case Must Be Dismissed For Failure To Prove

That She Had Applied For Admission To A Public

Housing Project.

In this action appellant’s primary objective is to enjoin

defendants from enforcing racial segregation in public

housing, so that she, and others similarly situated, may

be permitted to apply for admission to Fred Weasels

Homes and five other public housing projects in Savannah

which are presently limited to white occupancy, so that

their applications may be considered on the basis of stat

utory requirements for admission, without reference to

their race and color, and so that statutory preferences for

admission will be applicable to all vacant units and not

just to vacant units in projects limited to Negro occupancy.

Heyward, et al. v. P.H.A., et al., 238 F. 2d 689 (C. A. 5th,

1956).

In their answer to the complaint and upon the trial of

this cause defendant SHA and its officers admitted that

public housing in Savannah is operated on a racially

segregated basis (R. 28-30, 121).

Defendant PHA denied in its answer that the projects

are operated on a racially segregated basis (R. 34). How

ever, upon the trial of this case it was proved conclusively

that not only are pro jects operated on a racially segregated

basis with the knowledge and consent of PHA (R. 67-68)

but are so operated in an attempt to comply with PH A’s

racial equity requirement which is, in fact, a racial quota

requirement from which SHA cannot deviate without vio

lating its contract with PHA and without objection from

PHA (R. 54-55, 91-92, 181).

Therefore, in view of the fact that Fred Wessels Homes

and five other projects have been limited to white oecu-

11

pancy, it would have been a vain act for appellant to have

filled out an application form for admission to any of these

projects. This court and the Fourth Circuit have very

recently reaffirmed the well established principle that

equity does not require the doing of a vain act in cases in

volving gov ernmentally enforced racial segregation.

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade County, 246

F. 2d 913 (C. A. 5, 1957); School Board of City of Char

lottesville, Va. v. Allen, 240 F. 2d 59 (C. A. 4, 1956).

Consequently, the ruling of the court below was clear

error.

Despite the fact that appellant was not required to

prove that she had applied for projects limited to white

occupancy, appellant nevertheless proved that she had

attempted to make application for Fred Wessels Homes

but was told by a white male employee that the project was

not for Negroes (R. 132-133).

Appellant’s fruitless attempt to apply was corrob

orated by the person who accompanied her when she went

to the office in Fred Wessels Homes (R. 146-147).

Appellant’s testimony that there is an office upstairs

in Fred Wessels Homes with white male employes to

whom appellant could have spoken was corroborated bĵ

the testimony of Millard Williams who was the manager

of the Fred Wessels Homes at the time appellant attempted

to apply (R. 193-194).

The Defendant Secretary and Executive Director of

SHA testified that he had never seen appellant before the

trial (R. 186), but he also testified that he did not per

sonally take applications (R. 186). Therefore, his testi

mony did not contradict appellant’s testimony with regard

to her attempt to make an application in the Fred Wessels

Homes.

12

The manager of the Fred Wessels Homes testified that

appellant did not come to him (R. 187). But it is clear

from appellant’s testimony that she did not go into the

manager’s office which was on the ground floor (R. 192)

but to the executive offices upstairs (R. 144). The man

ager also admitted that it was possible for appellant to

have come in and that he did not see her (R. 191).

Thus, appellant established, without contradiction, that

she attempted to apply for a unit in Fred Wessels Homes,

after the buildings were completed but before anyone had

moved in, in the executive offices in one of the project’s

buildings, and that she was not permitted to apply solely

because of her race and color.

II. The Court Below Erred In Ruling That Appel

lant Failed To Prove That Defendants Refused Her

Any Preferential Right Of Occupancy Or That She

W as Entitled To A Preference.

The highest preference for admission to the public

housing involved in this case is the preference given to

servicemen and families of servicemen both by statute and

by the terms of the contract between PHA and SHA, Title

42, United States Code, "S 1410(g), Annual Contributions

Contract, Part II, Section 209 (Plaintiff’s Exhibit 1), and

as among such servicemen and families of servicemen,

preference is given to displaced families.

Appellant has a son who is presently serving in the

armed services (R. 133).

In addition, appellant was displaced as an indirect re

sult of the construction of Fred Wessels Homes (R. 204-

205). The testimony in this case also shows that the

overwhelming majority of persons directly displaced by

the construction of Fred Wessels Homes were Negroes

(R. 102-103).

13

Subject to the preferences given to servicemen and

displaced families, families having the greatest urgency

of need are also entitled to a preference for admission.

Title 42, United States Code § 1415(8) (c), Annual Con

tributions Contract, Part II, Section 208. The defendant

Secretary of SHA testified and the surveys attached to

the Development Programs show that the need for public

housing among Negro families in Savannah has always

been disproportionately greater than the need among white

families (R. 87, Plaintiff’s Exhibits 7 and 8). At the time

appellant sought admission to Fred Weasels Homes she

had received a notice from her landlord to vacate (R. 204).

She was forced to vacate because the house in which she

was living was torn down by a commercial establishment

which had been displaced by construction of Fred Weasels

Homes (R. 204-205). This made her need particularly

urgent and also established her eligibility. Annual Con

tributions Contract, Part II, Section 206(A)(3).

Annual Contributions Contract, Part II, Section 206

provides, in addition, that citizen families of service

men are eligible for admission if they are regularly living

together as a family of two or more persons related by

blood, marriage, or adoption and if they meet the income

requirements. This appellant’s family meets all of these

eligibility requirements (R. 133, 205).

The conclusion is thus inescapable that appellant and

the members of the class which she represents are precisely

the persons for whom the statutory preferences were

designed.

The Assistant Commissioner of PITA who testified for

PHA on the trial admitted that where projects are segre

gated the statutory preferences operate for Negroes only

with respect to those projects limited to Negroes and that

this is the interpretation placed on the statutes by PHA

1.4

(R. 172). He also admitted that it is the responsibility of

PHA to see that these statutory preferences are carried

out6 (E. 175).

Defendants therefore deny Negroes, as a group, the

preferences to which they are entitled, solely because of

race and color, and PHA fails to carry out its responsibility

under the statute to them. See, Heyward, et al. v. Public

Housing Administration, et al., 238 F. 2d 689, 697 (C. A. 5,

1956).

III. The Court Below Erred In Refusing To Grant

The Relief To Which Appellant Is Entitled.

The court below dismissed appellant’s cause of action

after a full trial on the merits which established the facts

set forth above. These facts clearly establish that appel

lant is entitled to 1) an injunction enjoining defendants

from enforcing racial segregation and racial quotas in

public housing; 2) an injunction enjoining defendants from

refusing to extend the statutory preferences for admissions

to appellant, and members of her class, to projects limited

to white occupancy; 3) an injunction enjoining defendant

SHA and its agents from refusing to accept and properly

consider appellant’s application, and the applications of

other Negroes, for admission to Fred Wessels Homes and

other projects limited to white occupancy; and 4) an in

junction enjoining PHA from giving financial and other

aid to SHA, in the future, for the construction, operation,

and maintenance of racially segregated projects. Heyward,

et al. v. Public Housing Administration, et al. 238 F. 2d

689 (C. A. 5, 1956).

Eule 54 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure pro

vides,

“ * * * Except as to a party against whom a judg

ment is entered by default, every final judgment

6 Sen. Rep. No. 84, 81st Cong., 1st Sess., 2 U. S. Code Con

gressional Service 1566 (1949).

15

shall grant the relief to which the party in whose

favor it is rendered is entitled, even if the party

has not demanded snch relief in his pleadings.”

Here appellant has demanded the relief which she now

claims she is entitled to as a result of the trial (R. 16-19).

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the

court below should be reversed and the court below

directed to grant the relief to which the appellant is

entitled as set forth above.

Respectfully submitted,

A. T. W alden,

200 Walden Building,

Atlanta 3, Georgia

Constance B aker Motley,

T hurgood Marshall,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York 36, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellant.

Supreme Printing Co., Inc., 54 Lafayette Street, N. Y. 13, BEekman 3-2320

*Hg8>»49

( 1434)