Federal Court Ends Segregation in Local Bus

Press Release

July 15, 1955

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Federal Court Ends Segregation in Local Bus, 1955. 67293739-bc92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/42c2559d-d451-4c74-89f9-b5e5cfb3beca/federal-court-ends-segregation-in-local-bus. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

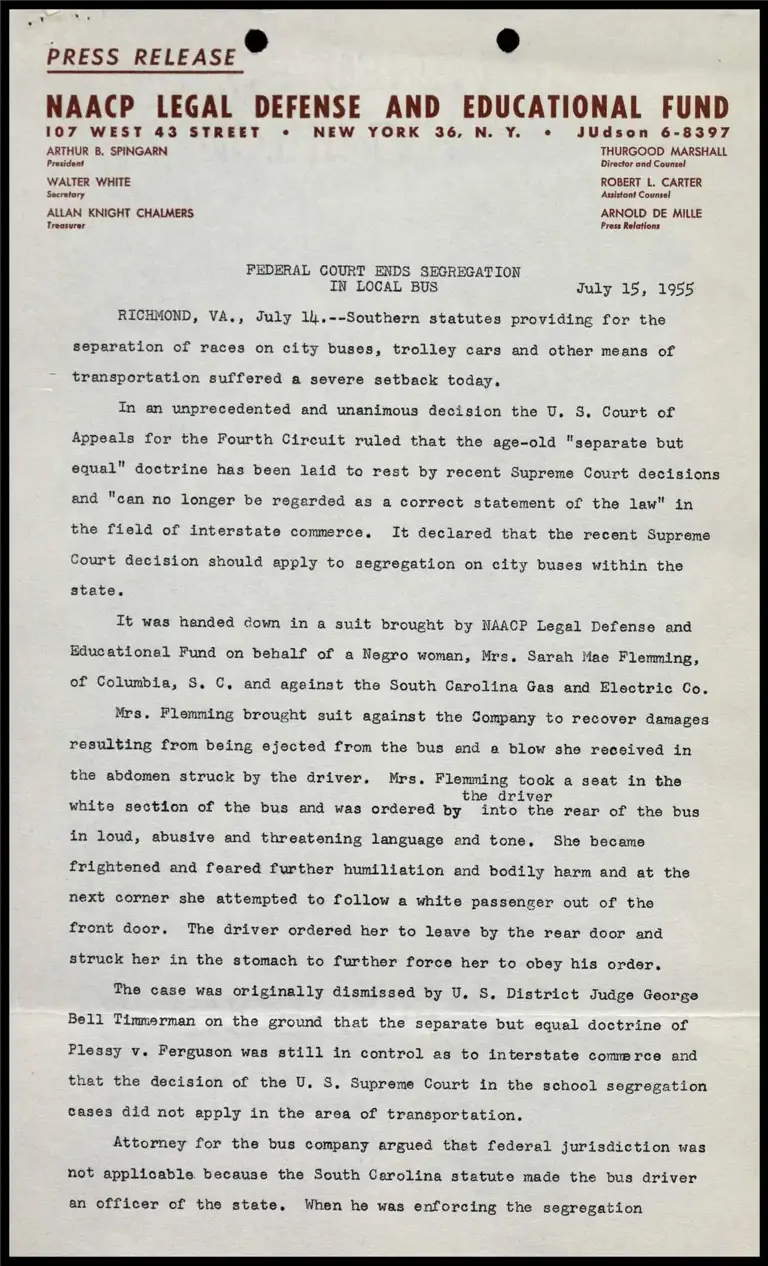

PRESS RELEASE @ bd

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

107 WEST 43 STREET + NEW YORK 36, N. Y¥. © JUdson 6-8397

ARTHUR B. SPINGARN THURGOOD MARSHALL

President Director and Counsel

ROBERT L. CARTER pslerllen els Aion! Coon

ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS ARNOLD DE MILLE

Treasurer Press Relations

FEDERAL COURT ENDS SEGREGATION

IN LOCAL BUS July 15, 1955

RICHMOND, VA., July 1).--Southern statutes providing for the

separation of races on city buses, trolley cars and other means of

transportation suffered a severe setback today.

In an unprecedented and unanimous decision the U. 3. Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit ruled that the age-old "separate but

equal" doctrine has been laid to rest by recent Supreme Court decisions

and "can no longer be regarded as a correct statement of the law" in

the field of interstate commerce. It declared that the recent Supreme

Court decision should apply to segregation on city buses within the

state.

It was handed cown in a suit brought by NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund on behalf of a Negro woman, Mrs. Sarah Mae Flemming,

of Columbia, S. C, and against the South Carolina Gas and Electric Co.

Mrs. Flemming brought suit against the Sompany to recover damages

resulting from being ejected from the bus end a blow she received in

the abdomen struck by the driver, Mrs. Flemming took a seat in the

the driver

white section of the bus and was ordered by into the rear of the bus

in loud, abusive and threatening language and tone, She became

frightened and feared further humiliation and bodily harm and at the

next corner she attempted to follow a white passenger out of the

front door. The driver ordered her to leave by the rear door and

struck her in the stomach to further force her to obey his order,

The case was originally dismissed by U. S. District Judge George

Bell Timmerman on the ground that the separate but equal doctrine of

Plessy v. Ferguson was still in control as to interstate comerce and

that the decision of the U. S. Supreme Court in the school segregation

cases did not apply in the area of transportation.

Attorney for the bus company argued that federal jurisdiction was

not applicable because the South Carolina statute made the bus driver

an officer of the state. When he was enforcing the segregation

regulation on the bus he was not acting for the company but as an

EY

officer of the state.

South Carolina statutes provides for the segregation of the races

on motor vehicles in both city and intrastate carriers and empowers

bus drivers or operators with special police authority to arrest per-

sons who violate the bus segregation laws.

Attorney Robert L. Carter who argued the appeal on behalf of

Mrs, Flemming declared that there could be no question as to the juris-

diction of the federal court. He contended that the bus driver in

enforcing the state segregation stetute was acting as both bus driver

and officer of the state. Mr. Carter contended also that the bus

company was charged by the South Carolina statute with the duty to

enforce the law. He argued further that the recent Supreme Court

decisions had swept away all support for the separate but equal doctrine

even as applied to intrastate commerce.

In handing down the decision today, the Fourth Circuit Court of

Appeals struck down the South Cerolina state segregation statute,

reversing the district court's decision and remanded it back to the

lower court.

The decision in this case is highly significant in thet it means

that segregation in local streetcars, buses and other means of trens-

portation can no longer be enforced. The Fourth Circuit Court of

Appeals has jurisdiction over the states of South Carolina, North

Cerolina, West Virginia and Maryland. Unless the U. S. Supreme Court

reverses this decision in these states, the circuit court ruling of

today can be applied,

=30=

Icc ASKED TO END SEGREGATION

IN INTERSTATE TRAVEL July 15, 1955

WASHINGTON, D.C., July 1).--The segregation of Negro passengers

traveling through states which have enforced bias laws is an "unwar-

ranted misuse" of the Interstate Commerce Act, Robert L. Carter, First

Assistant Counsel of the NAACP's Legal Defense and Hducational Fund,

told eleven members of the Commission here today.

Congress has empowered the Commission with the authority to

overrule any railroad's regulation which calis for the separation of

passengers because of race or color, Mr. Carter said. He called upon

the Interstate Commerce Commission to use this power and put an end to

the railroad! long practice of racial segregation in interstate travel,

In what is regarded as a direct attack on segregation in railroad

coaches, waiting-room fecilities and eating places in railroad termin-

als, Attorney Carter appeared before the Interstate Commerce Commission

in behalf of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored

# @

-3-

People and 21 individuals who brought discrimination charges against

eleven railroads, the Richmond (Va.) Terminal Railway Co., and the

Union News Co., operator of the eating facilities at the Broad Street

Station in the Richmond Terminal,

Following the filing of the charges with the Commission, an ICC

Examiner, Howard Hosmer, in a proposed report claimed that the rail-

roads! segregation practice "subjected Negro passengers to unreasonable

disadvantages in violation of Section 3(1) of the Interstate Commerce

Commission Act." His report asked for the end of segregation in

interstate travel,

In the matter of restaurant facilities, however, Examiner Hosmer

held that the Interstate Commerce Commission does not have jurisdic-

tion and cannot order an end to discriminetory policy in respect to

the use of these facilities.

The proposed report brought sharp exceptions from the eleven

railroads and the Richmond Railway Terminal. Each asked for time to

argue before the Interstate Commerce Commission, but only attorneys

for the Richmond Terminal Company, Illinois-Central and the Texas and

Pacific Railroads appeared today.

NAACP Legal Defense attorneys took exception to that phase of the

Examiner's report which held that the Interstate Commerce Commission

did not have jurisdiction over the eating facilities at the Broad

treet Station, and that the Commission did not have the power to

order the Union News Co. to cease its Jim Crow practices.

In this connection, Mr. Carter argued that the eating facilities

at the Station do come under the Interstate Commerce Commission's

jurisdiction since it is a part of the property owned and operated by

the Richmond Railway Company for the convenience of passengers. The

Terminal Company must abide by the ICC's regulation ond so should the

Union News Co., attorney Carter said.

Attorney for the Richmond Terminal Company, Charles C, Reynolds,

contended that the lease granted the Union News Company "keeps the

Terminal Company from being liable."

Attorney Reynolds defended the Terminal's maintenance of signs

designating "white" and "colored" waiting and restrooms. He said there

is no required segregation. Attendants have been “instructed not to

interfere" with Negroes using either, he asserted,

* @

he

In answer to the Commission's question as to the purpose of the

"colored" and "white" signs, Attorney Reynolds said they were to give

the Negro people a chance to associate with each other.

"We believe that colored persons desire to associate with persons

of their own race and white persons desire to associate with persons of

the white race," he replied.

In reply to this remark, Mr, Carter said thet the theory that

Negroes wanted to be segregated has no basis. As to this contention,

it is immaterial because even if the railroads were correct the right

to equal treatment is a personal right to each individual which cannot

be limited in any way by what Negroes do or want to do.

Attorneys for the Illinois-Central and the Texas and Pacific

Railroads asked the Commission to dismiss the charges against them

because of the lack of substantial evidence.

This case is considered one of the most far-reaching and signifi-

cant attacks on segregation since the school segregation cases. The

Commission may hand down its decision early this fall.

SARAH KEYS

Heard also today was the complaint of Miss Sarah Keys, a former

member of the Women's Army Corps who was abused and arrested in Roanoke

Rapids, N. C,, in 1952 for refusing to move from a bus seat when ordered

by a driver.

She was traveling in uniform and was en route from Fort Dix, N.J.,

where she was stationed, to her home in Washington, N.C, A joint line

ticket was issued to her for transportation over three bus lines, Safe-

way Trails, Virginia-Trailways and the Carolina Coach Co. She had no

difficulty until she reached Roanoke Rapids, a station stopping point,

at 12:20 a.m. on August 2, 1952, where there was a change of bus driver.

Upon noticing that she was sitting in the third seat from the

front, the driver ordered her to move to the back and sit in a seat

occupied by a white Marine, She insisted that the seat was quite

comfortable and maintained that she had a right to retain her seat.

The driver then consulted with the dispatcher regarding the sit-

vation, He returned and told all of the other: passengers to leave the

bus and board another. He told Miss Keys: "Just keep your seat."

When she tried to board the second bus, the driver blocked the

door and refused to let her on. Pleas to local authorities for aid

resulted in her arrest and a fine for disorderly conduct.

@ @

age

Following payment of the fine, a civil action was filed against

the Cerolina Coach Company in the U, S. District Court for the District

of Columbia. The action was thrown out on the theory that the bus

company was not doing business in the District of Columbia. On

September 1, 1953, the complaint against the bus company was filed with

the Interstate Commerce Commission.

A hearing was held on May 12, 1954, before ICC Examiner Isadore

Freidson. On September 30, he dismissed the complaint with the ruling

that the Carolina Coach Co, did not subject Miss Keys to "any unjust

discrimination or undue and unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage"

and did not violate the Interstate Commerce Act.

At the hearing this morning, NAACP Legal Defense attorney Frank

D, Reeves said that this is a “very clear case of discrimination."

The basic and fundamental issue is whether the company's regula-

tion which segregates passengers because of race is a violation of the

Interstate Commerce Act, Mr, Reeves indicated. The "separate but

equal” doctrine has nothing to do with the issue whatsoever, he said.

"That doctrine has now been laid to rest by the United States Supreme

Court."

He asked the Commission to reconsider Examiner Freidson's dis-

missal of the complaint and give a new opinion in light of the recent

Supreme Court decisions.

The arguments ended at 12:43. The Commission did not indicate

when it might render its ruling.

The complaint against the railroads was filed on December 1), 1953,

by NAACP Legal Defense attorneys in behalf of the N.A.A.C.P. and 21

individuals, The attorneys were Thurgood Marshall, Director-Counsel,

and Mr. Carter, Attorneys for Miss Keys were Frank D. Reeves, Dovey J.

Roundtree and Julius W. Robertson of Washington, D. C.

=30-