Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Reply Brief for Petitioner on Reargument

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Reply Brief for Petitioner on Reargument, 1988. 6aad32a6-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/42c78609-6676-4087-b7ef-ff55d5df9293/patterson-v-mclean-credit-union-reply-brief-for-petitioner-on-reargument. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

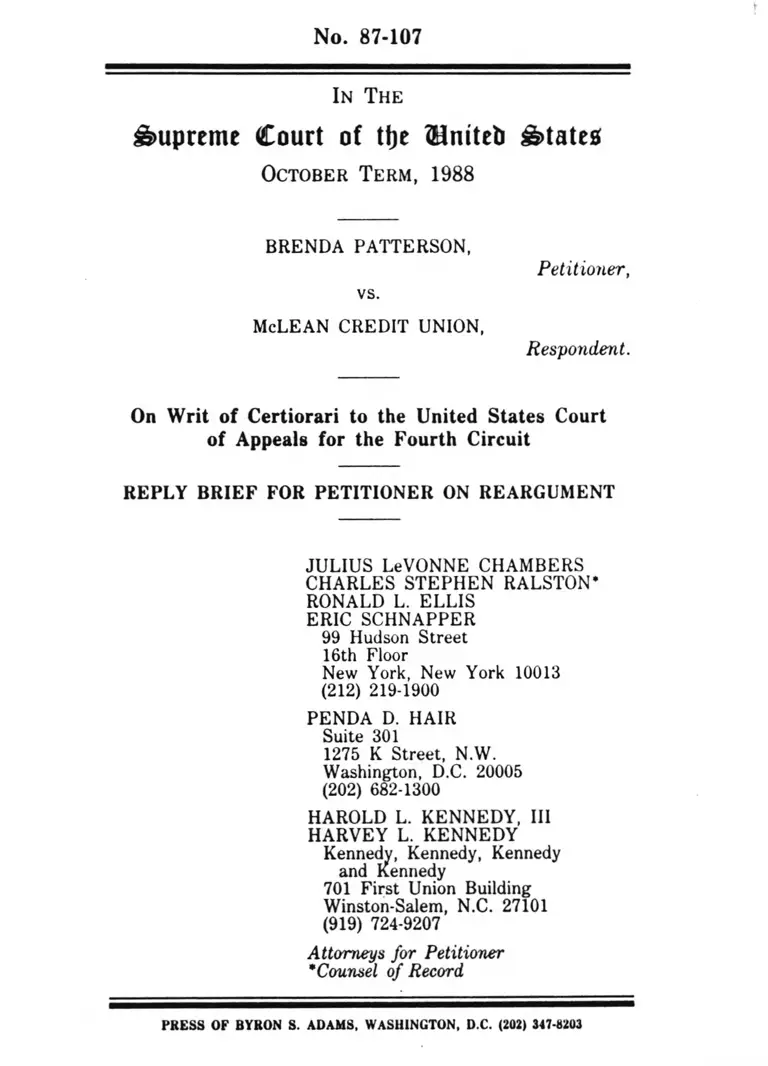

No. 87-107

In T he

Suprem e Court of tfje ftlmtet) S ta te s

O ctober Te r m , 1988

BRENDA PATTERSON,

vs.

McLEAN CREDIT UNION,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONER ON REARGUMENT

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON*

RONALD L. ELLIS

ERIC SCHNAPPER

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

PENDA D. HAIR

Suite 301

1275 K Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

HAROLD L. KENNEDY, III

HARVEY L. KENNEDY

Kennedy, Kennedy, Kennedy

and Kennedy

701 First Union Building

Winston-Salem, N.C. 27101

(919) 724-9207

Attorneys for Petitioner

*Counsel of Record

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS. WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY ........ 1

I. RESPONDENT'S PROPOSED INTER

PRETATION OF SECTION 1981

IS NEITHER WORKABLE NOR

CONSISTENT WITH THE LEGIS

LATIVE HISTORY OF THE 1866

CIVIL RIGHTS ACT ............ 3

A. Respondent's Interpre

tation of Section 1981

Is Not Workable........ 8

B. The Actual Terms of the

Black Codes Undermine

Respondent's Interpre

tation of Section 1981.. 14

II. THE 1870 VOTING RIGHTS ACT

CONFIRMS THAT CONGRESS UNDER

STOOD SECTIONS 16 AND 18 OF

THAT ACT, LIKE SECTION 1 OF

THE 1866 ACT, TO APPLY TO

PRIVATE CONDUCT ............. 22

III. THE 1874 REVISED STATUTES

DID NOT REDUCE THE SUBSTAN

TIVE PROTECTIONS OF THE 1866

CIVIL RIGHTS ACT ............ 29

IV. THE DOCTRINES OF CONGRES

SIONAL RATIFICATION AND

STARE DECISIS COMPEL REAFFIR

MATION OF THE DECISIONS IN

RUNYON AND JONES ............ 33

A. Respondent Would Nullify

Stare Decisis .......... 33

B. Congress Approved Jones

and Runvon ............. 3 8

C. Congress and Not the

Court Is Competent to

Address the Interaction

of Title VII and § 1981. 39

CONCLUSION ........................ 4 5

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385

(1986) 12

The Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S.

3 (1883) 7

District of Columbia v.

Thompson Co., 346 U.S. 100

(1953) 32

Jones v. Mayer Co., 392 U.S.

409 (1968) passim

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail

Transp. Co., 427 U.S. 273

(1976) 39

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167

(1961) 37

Ruckelshaus v. Monsanto Co.,

467 U.S. 986 (1984) 31

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S.

160 (1976) passim

United States v. Guest,

383 U.S. 745 (1966) 7

United States v. Kozminski,

101 L. Ed. 2d 788 (1988) ....... 5, 32

Yick Wo v. Hopkins,

118 U.S. 356 (1886) 26

iii

Thirteenth Amendment,

United States Constitution .... 5

Fourteenth Amendment,

United States Constitution .... 4,6,7

Fifteenth Amendment,

United States Constitution .... 24

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ................ passim

42 U.S.C. § 1982 ................ passim

Civil Rights Act of 1866 ....... passim

Voting Rights Act of 1870 ...... passim

Civil Rights Act of 1875 ....... 6

Civil Rights Attorney's Fees

Awards Act of 1976 ............ 38, 39

Revised Statutes of 1874 ....... 2, 29

30, 31

16 Stat. 140 .................... 9

17 Stat. 13 ..................... 9

18 Stat. 713 ..................... 32

Florida Constitution 1865 ...... 17

Texas Constitution 1866 ........ 17, 19

Arkansas Laws 1866-67 ........... 17, 19

Florida Laws 1864-65 ............ 17, 18

Statutes and Constitutional Page

Provisions:

IV

Statutes and Constitutional

Provisions: Page

Georgia Laws 1866 ............... 17, 19

Mississippi Laws 1865 ........... 18, 19

South Carolina Laws 1874-65 .... 17, 18

19, 21

Tennessee Laws 1865-66 .......... 19

Texas Laws 1866 .................

Legislative Authorities:

17, 19

H.R. Rep. No. 1558, 94th Cong.,

2d Sess. (1976) ............... 39

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong.,

1st Sess........................ 4, 6

Cong. Globe, 41st Cong.,

2d Sess......................... 24 , 28

29

Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong.

2d Sess......................... 6, 7

Cong. Globe, 43rd Cong.

1st Sess........................ 6

118 Cong. Rec. (1972) ........... 43

Staff of the House Comm, on

Educ. & Labor, 99th Cong.,

2d Sess., Investigation of

Civil Rights Enforcement By

the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission (Comm.

Print 1986) ................... 44

v

Other Authorities: Page

Brief for the United States as

Amicus Curiae, Jones v.

Maver Co. ...................... 17

Office of Program Compliance,

EEOC, Annual Report F.Y.

1986............................ 44

Govt. Accounting Office, EEOC

Birmingham Office Closed

Discrimination Charges Without

Full Investigation (July 1987) . 44

Abbott's National Digest (1884) . 32

T. Eisenberg & S. Schwab, The

Importance of Section 1981,

73 Cornell L. Rev. 596 (1988) . 42, 43

W. Eskridge, Jr., Overruling

Statutory Precedents, 76 Geo.

L. J. . 1361 (1988) 34

W. Fleming, Documentary History

of Reconstruction

(1906) 18

McClain, The Chinese Struggle for

Civil Rights in Nineteenth

Century America: The First

Phase, 1850-1870, 72 Cal. L.

Rev. 529 (1984) 25

A. Saxton, The Indispensable

Enemy (1971) 27

J. tenBroek, Equal Justice

Under Law (1951) 29

vi

Other Authorities: page

The Supreme Court 1986 Term,

The Statistics, 101 Harv. L.

Rev. 362 (1987) 36

West Virginia University, Laws

Relating to Freedmen (1904) ... 18

C. Wollenberg, ed., Ethnic

Conflict in California

(1970) 27

vii

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY

Respondent has failed to propose a

coherent and workable definition of the

scope of §§ 1981 and 1982. Instead,

respondent ignores fundamental problems

with arguments for overruling Jones v.

Maver Co.. 392 U.S. 490 (1968), and Runvon

v. McCrary. 427 U.S. 160 (1976). First,

respondent fails to deal with Justice

Harlan's conclusion in his Jones dissent

that the 1866 Civil Rights Act was

i n t e n d e d to e x t e n d to private

discrimination that is "customary" or in

accord with "public sentiment." This

conclusion is compelled by the language of

the Act and by legislative history

indicating that it was intended to cover

such private discrimination as employers

who refused to pay black workers.

However, Justice Harlan's intermediate

p o s i t i o n on coverage of private

discrimination would lead the courts into

2

a quagmire of legal and factual questions

concerning the meaning of custom and its

proof in individual cases.

Second, respondent's arguments

concerning the legislative history of the

1870 Voting Rights Act and the 1874

Revised Statutes are premised on the

notion that §§ 1981 and 1982 are different

in scope. Respondent thus asks the Court

to rule that Jones was correctly decided,

but to hold that § 1981, unlike § 1982,

does not reach private discrimination.

This unlikely incongruity between the

scope of §§ 1981 and 1982 would produce

strange results and extensive litigation

over whether specific transactions can be

characterized as "property," rather than

"contract."

As we show below, the actions of

Congress in 1866, 1870 and 1874 do not

support this interpretation of the scope

3

of § 1981. To the contrary, the

legislative history strongly supports the

conclusion that both §§ 1981 and 1982

p r o h i b i t p u r e l y pri va te racial

discrimination, as well as state-

sponsored discrimination. Furthermore,

the unworkability of respondent's

position, as well as traditional concepts

of congressional ratification and stare

decisis, mandate reaffirmation of Jones

and Runvon.

I. RESPONDENT'S PROPOSED INTERPRETATION

OF SECTION 1981 IS NEITHER WORKABLE

NOR CONSISTENT WITH THE LEGISLATIVE

HISTORY OF THE 1866 CIVIL RIGHTS ACT

In our opening brief we showed that

in 1866 the central problem faced by

freedmen was that, although legally able

to make contracts, they were prevented by

various forms of private discrimination

and abuse from making, and enforcing,

employment contracts on equitable terms.

The income and working conditions of the

4

freedmen, as Congress was well aware, were

in many instances almost as bad as they

had been under slavery.1 Respondent does

not seriously dispute our description of

the plight of blacks in the south after

the end of the Civil War, but argues that

Congress made a deliberate decision not to

protect the freedmen from much of the

mistreatment to which they were then

subj ect.

Although contemporary Fourteenth

1 Respondent asserts that there

is only a single "fleeting reference to

the Grant Report." Resp. Rearg. Br. 88.

In fact, the Grant Report was read in full

on the floor of the Senate, Cong. Globe,

39th Cong., 1st Sess. 78, cited in the

debates in both Houses, id. at 79, 97,

109-11, 1834, 1839, and reprinted in large

quantities by order of Congress, id. at

59-60, 67, 129, 136, 160, 265, 422. The

Howard Report was also printed by Congress

for public distribution. Id. at 138. The

hearings of the Joint Committee played a

pivotal role in the debates on whether to

override President Johnson's veto. Id. at

1799, 1808, 1827, 1833-35. The Schurz

Report played a critical role in the

evolution of Congressional reconstruction

policy. See Appendix A.

5

Amendment jurisprudence distinguishes

between private and governmental conduct,

that was not a distinction of importance

to either the supporters or the opponents

of the 1866 Civil Rights Act. The

Thirteenth Amendment, approved by Congress

less than a year earlier, and the

constitutional basis for § 1, "extends

beyond state action." United States v.

Kozminski. 101 L.Ed.2d 788, 804 (1988).

Having already taken, by constitutional

amendment, the far more drastic step of

stripping the former slave owners of their

property rights in the slaves, it is

unlikely Congress would have balked at the

relatively modest additional step of

forbidding those slave owners to treat

freedmen in a discriminatory manner.

Even the critics of the 1866 Act

expressed no opposition as such to

legislation regulating private conduct;

6

on the contrary, they repeatedly insisted

that they would support such legislation

if only the range of abuses it prohibited

were narrower.^

An implied distinction between

private and public conduct cannot be

inferred from the fact that § 1 of the

1866 Act was later reenacted under the

authority of the Fourteenth Amendment.

As it demonstrated in adopting the 1875

public accommodations law,3 Congress in

Cong. Globe 39th Cong., 1st

Sess. 595-97 (Sen. Davis), 601 (Sen.

Guthrie), 1156-57 (Rep. Thornton), 1805

(Sen. Doolittle).

A m i c i s u g g e s t that the

enactment of this measure shows that

Congress believed that discrimination in

public accommodations was legal prior to

1875. The debates on the 1875

legislation, however, reveal that many

s u p p o r t e r s b e l i e v e d t ha t such

discrimination was already illegal, and

favored the 1875 Act either to remove any

doubts about that issue, or to provide an

additional remedy, particularly the

provision for $500 liquidated damages in

§ 2, 18 Stat. 336. See Cong. Globe, 42nd

(continued...)

7

the Reconstruction era believed that it

had authority under the Fourteenth

Amendment to regulate private conduct, a

view that was ultimately accepted by this

Court. Compare United States v. Guest.

383 U.S. 745 (1966), with The Civil Right?;

Cases. 109 U.S. 3 (1883).

Respondent suggests that the highest

p r i o r i t y of R e c o n s t r u c t i o n era

Republicans was not protecting the

freedmen, but safeguarding the states

against the federal government, bringing

about the prompt readmission of the

former rebel states, and assuring that

employer-employee and other contractual

relations were not interfered with by

statute. Resp. Rearg. Br. 48-51. The

political philosophy which respondent 3

3 (...continued)

Cong., 2d Sess. 3192 (1872) (Sen. Sherman);

43rd Cong., 1st Sess. 341 (1873)(Rep.

Butler); id. at 410 (1874)(Rep. Elliott).

8

describes, however, is not that of the

congressional Republicans, but of

President Andrew Johnson, and it is the

philosophy which prompted Johnson to veto

the 1866 Civil Rights Act.

A. RESPONDENT'S INTERPRETATION OF

SECTION 1981 IS NOT WORKABLE

The t h r e s h o l d p r o b l e m with

respondent's analysis is that it does not

yield a clear and workable construction

of § 1981. Justice Harlan, in his

dissenting opinion in Jones, did not

assert that § 1 of the 1866 Civil Rights

Act applies only to state sponsored

discrimination, but repeatedly insisted

that § 1 extends as well to actions taken

by n o n - o f f i c i a l s in line with

discriminatory customs/ Justice Harlan 4

4 Justice Harlan's recognition of

this application of § 1 was compelled by

the terms of § 2, which imposed criminal

penalties for violations of § 1 which

occurred "under color of any law,(continued...)

9

urged, for example, that a refusal to pay

black workers would be a "custom" within

the meaning of § 1, as would an agreement

among employers not to hire a former slave

without the permission of former master.^

Discrimination in public accommodations,

Harlan suggested, would also be prohibited

by the law if it were a customary 4

4 (...continued)

statute, ordinance, regulation or

custom," 14 Stat. 27 (emphasis added).

Jones v. Mayer Co.. 392 U.S. 409, 454-55

(1968) (dissenting opinion). In § 2,

unlike provisions of other civil rights

legislation of this era, the word

"custom" was not modified by the phrase

"of any State." Compare 16 Stat. 140; 17

Stat 13.

392 U.S. at 462 ("there was a

strong 'custom' of refusing to pay slaves

for work done"), 470-71 ("the references

to white men's refusals to pay freedmen

and their agreements not to hire freedmen

without their 'masters' consent are by no

means contrary to a 'state action' view of

the civil rights bill, since the bill

expressly forbade action pursuant to

'custom' and both of these practices

reflected 'customs' from the time of

slavery") .

10

practice.® Indeed, on Justice Harlan's

view any d iscriminatory practice

reflecting a "prevailing public sentiment"

would be unlawful.* * 7 Although Justice

Harlan characterized his interpretation of

the 1866 Act as involving a requirement of

"state action," he carefully put those

two words in quotation marks throughout

his opinion, recognizing that he was

using the phrase in an unusual and

s p e c i a l i z e d m a n n e r . 8 Respondent

392 U.S. at 464 (Senator Davis'

assertion that § 1 covered discrimination

in accommodations in ships, hotels,

railroad cars and churches was correct,

and thus elicited no reply, because he

d e s c r i b e d t h e s e p r a c t i c e s as

"'discriminations ... made by ... custom'

. . . and . . . tied these effects of the

bill to its 'customs' provision").

392 U.S. at 463; see also id. at

462 n.28 (private abuses proscribed by the

bill "to the extent that the described

discrimination was the product of custom").

392 U.S. at 457, 458, 459, 462,

Similarly, Justice Harlan

(continued...)

4 7 3 .

11

apparently embraces Justice Harlan's

intermediate view of § l.8 9

While § 1, as Justice Harlan

acknowledged, reaches beyond state action

in the constitutional sense, Justice

Harlan's attempt to draw a line short of

what he described as "purely private"

conduct is unworkable. Justice Harlan's

opinion offers three quite distinct

definitions of a § 1 custom: practices

that existed "from the time of slavery,"

392 U.S. at 471, practices "pursuant to 'a

prevailing public sentiment,'" 392 U.S. at

463, and practices "which were legitimated

by a state or community sanction

sufficiently powerful to deserve the name

custom." 392 U.S. at 457. Justice Harlan

8 (...continued)

consistently described conduct outside the

scope of § 1, not simply as private, but

as "purely private." id. at 461, 463,

465, 473.

9 Resp. Rearg. Br. 86, 67, 81, 111.

12

saw no need to explicate what such

definitions might mean in operation,

noting only that the plaintiff in Jones

had made no allegation of any such custom.

392 U.S. at 476 n.65. But in practice the

implementation of Justice Harlan's

proposed construction would be plagued by

intractable disputes. Virtually any case

brought under § 1981 or § 1982 would raise

legal and factual issues regarding how

w i d e s p r e a d the alleged type of

discrimination was within the defendant

entity, or the local community, and how

closely it resembled abuses in the ante

bellum south. -*-0

However difficult these issues would 10

10 For example, given numerous

recent findings of race-based employment

discrimination in North Carolina, e .g ..

Bazemore v. Friday. 478 U.S. 385 (1986),

petitioner in the instant case would have

a s t r o n g a r g u m e n t t h a t s u c h

discrimination is customary in that State.

13

be today, there can be no doubt that,

even on Justice Harlan's view, the

allegations of the instant complaint

would have stated a cause of action had

the complaint been filed in 1867 rather

than in 1984. The abuses alleged in

petitioner's complaint were widespread a

century ago, and resembled the abuses

inflicted on slaves prior to the Civil

War. McLean Credit Union, had it existed

in 1867, could not have treated petitioner

in the discriminatory manner she now

alleges to have occurred. It seems

unlikely that Congress intended that an

employer might at a later date be

permitted to engage in such abuses solely

because some other employers in North

Carolina have ceased to do so, or because

the discriminatory practices once

su pp o rt e d by " prevailing public

sentiment" in that State might have

14

become less socially acceptable.

B . THE ACTUAL TERMS OF THE BLACK

CODES UNDERMINE RESPONDENT'S

INTERPRETATION OF SECTION 1981

The linchpin of respondent's

construction of § 1 of the 1866 Civil

Rights Act is its contention that the

exclusive purpose of that provision was

to nullify discriminatory provisions of

the post-civil War Black Codes. In fact,

however, there were no post-civil War

laws in the south which deprived freedmen

of the legal capacity to contract. A

review of the actual provisions of the

Black Codes not only undermines

respondent's interpretation of § 1 , but

explains the seemingly contradictory

tenor of congressional statements.

Some problems, such as testimony by

black witnesses in cases in which all

parties were white, were indeed the

subject of widespread discriminatory

15

legislation, and in those instances

Congress may have been primarily

concerned with nullifying such laws.11 In

other areas, particularly the right to

make contracts and to own property, the

Black Codes generally guaranteed blacks

the same legal capacity as whites; here

the concerns of Congress necessarily lay

elsewhere, with the systematic private

abuses described in our earlier brief.

The seemingly inconsistent legislative

explanations of the purpose of § 1 stem,

at least in part, from the fact that

11 See A p p e n d i x B. Amic us

Washington Legal Foundations urges that

Congress intended to solve the widespread

private mistreatment of blacks by

nullifying state laws which prohibited

testimony by the black victims of such

abuses, asserting that "crimes of

violence against ... freedmen went

unpunished since blacks could not testify

in a court of law." Brief Amicus Curiae

of Washington Legal Foundation, at 16.

In fact, however, there were by 1866 no

such statutory prohibitions in any of the

southern states.

16

different provisions of § 1 addressed

distinct types of problems.

It is particularly clear that the

provisions of § 1 with regard to owning

and leasing property cannot be explained

as a measure enacted to overcome

discriminatory legislation. In the

government's brief in Jones . the

Solicitor General correctly observed that

none of the Black Codes prohibited the

ownership of real property by blacks:

[H]owever discriminatory they were,

it does not appear that any of the

Black Codes denied the capacity of

the Negro to acquire and hold

property, real or personal. On the

contrary, one standard history,

summarizing these laws, observes

that they "conferred upon the

freedmen fairly extensive privileges

[and] gave them the essential rights

of citizens to contract, sue and be

sued, own and inherit property...."

Morrison and Commager, The Growth of

the American Republic (1950)....

[T]he real problem for the Congress

in 1866 was not to nullify local

statutes which wholly disabled the

Negro with respect to property, or

even to clarify his status on this

17

score.12

Five of the Black Codes contained express

guarantees of the right of blacks to own,

hold or inherit property; the Georgia

statute provided, for example, that

"persons of color shall have the right

... to purchase, lease, sell, hold and

convey, real, and personal property."13

Among the state laws adopted in this era

only a statute enacted by Mississippi in

November of 1865, and not emulated by any

other State, placed restrictions on the

ability of blacks to lease property.14

12 Brief for the United States as

Amicus Curiae 30-31, Jones v. Mayer Co. ,

392 U.S. 490 (1968) (emphasis in

original).

12 Georgia Laws 1866, p. 239. See

also Arkansas Laws 1866-67, p. 99;

Florida Const'n. 1865, art. xvi; Florida

Laws 1864-65, p. 145; South Carolina Laws

1864-65, p. 271; Texas Const'n. 1866, art.

27; Texas Laws 1866, p. 27.

14 Mississippi Laws 1865, p. 82 et

seq. Legal prohibitions against the

(continued...)

18

Restrictions on the ownership of personal

property by freedmen were equally

uncommon. Six states adopted express

guarantees of the right of blacks to own

such property.14 15

As the United States also observed

in its brief in Jones. none of the Black

Codes contained prohibitions forbidding

blacks to make or enforce contracts. On

the contrary, the general purpose of

14(...continued)

actual ownership of land by freedmen were

apparently limited to identically worded

ordinances adopted by two Louisiana

parishes in July, 1865. W. Fleming,

Documentary History of Reconstruction 279

(1906); West Virginia University, Laws

Relating to Freedmen 31 (1904).

15 In addition to the authorities

cited in note 13, supra. see Mississippi

Laws 1865, p. 82. The only exceptions

were in South Carolina, which forbade

blacks from owning either distilleries or

certain types of firearms, and two other

states which required blacks, but not

whites, to obtain a license in order to

possess a lethal weapon. Florida Laws

1864-65, p. 25; Mississippi Laws 1865, p.

82 et seq.; South Carolina Laws 1864-65.

19

southern laws of this era was to

encourage blacks to sign contracts,

especially labor contracts. a South

Carolina statute adopted in December 1865

provided in part

The s ta tutes and regulations

c o n c e r n i n g s l a v e s are n ow

inapplicable to persons of color;

... such persons shall have the

right ... to make contracts, to

enjoy the fruits of their labor; to

sue and be sued....16

Four other states followed South Carolina

in enacting express guarantees of the

right to make and enforce contracts.17

Although a freedman generally might not

be able to testify in a civil suit

between two whites, he was expressly

guaranteed the right to testify in any

contract case in which he was a party.1®

■LC> South Carolina Laws 1864-65, p.271.

17 Arkansas Laws 1866-67, p. 99;

Georgia Laws 1865-66, p. 239; Tennessee

Laws 1865-66, p. 65; Texas Const'n. 1866,

art. 27; Texas Laws 1866, p. 27.

18 See Appendix B.

20

Although there were a few racially

explicit post-Civil War southern laws

which affected the contracts of freedmen,

it is unlikely that these were the sole

problem at which the contract provision

of § 1 was directed. First, it is clear

that the property provisions of § 1 apply

to purely private conduct, as recognized

by the dissenting opinion in Runyon. It

is unlikely that Congress would have

intended, in 1866, 1870 or 1874, to limit

the contract provision in § 1 to state

action. Placing in the contract provision

a state action requirement absent from the

property provisions would lead to strange

and often unworkable distinctions between

contracts for the sale or lease of

property and other forms of contract.

Private contracts with tenant farmers

would be covered by § 1, but private

contracts with farm laborers would not.

21

Private school admissions would be

subject to § 1 if students stayed in

leased dormitory rooms, but not if they

went home at night. It would be illegal

for a white blacksmith to refuse on

racial grounds to sell a horseshoe to a

former slave, but the blacksmith could

refuse to nail the shoe to the hoof of

the freedmen's horse.

Second, among the eleven former

confederate states, only South Carolina

adopted legislation limiting the ability

of blacks to engage in a trade19 or

regulating the conditions of black

employment.20 It would be surprising

indeed if Congress, although aware of the

dreadful conditions under which millions

of freedmen worked all across the south,

19 South Carolina Laws 1864-65,

274, 299.

20 Id. at 295-97.

22

had decided to address that problem only

in South Carolina, and to leave untouched

identical working conditions in the ten

other former rebel states.

II. THE 1870 VOTING RIGHTS ACT CONFIRMS

THAT CONGRESS UNDERSTOOD SECTIONS 16

and 18 OF THAT ACT, LIKE SECTION 1 OF

THE 18 66 ACT, TO APPLY TO PRIVATE

CONDUCT________________________________

Although we believe the scope of §

16 of the 1870 Voting Rights Act is not

dispositive here, a close reading of the

language and legislative history makes

clear that Congress understood § 16 to

cover private acts of discrimination. A

review of the 1870 Act as a whole reveals

that the Forty-first Congress carefully

considered which provisions would and

would not deal with state laws or

activities, and that when Congress had in

mind state action it said so expressly.

Of the twenty-three sections in that Act,

seven expressly refer to state action.

23

Sections 2 and 3, for example, concern

actions "under the authority of the

constitution or laws of any State, or the

laws of any Territory," and § 22 deals

with certain acts "required ... by any law

of the United States, or of any State or

Territory thereof."21 Section 16 of the

Act, from which § 1981 derives in part,

actually contained two sentences, the

second of which was expressly limited to

discriminatory state action:

All persons within the jurisdiction

of the United States shall have the

same right in every State and

Territory in the United States to

make and enforce contracts.... No

tax or charge shall be imposed or

enforced by any State upon any

person immigrating thereto from a

foreign country which is not equally

imposed and enforced upon every

person immigrating to such State from 16

16 Stat. 140, 146. See also 16

Stat. 140-44, § 1 ("any constitution, law,

custom, usage or regulation of any State

or Territory"), §§ 16, 17 (referring both

to acts "under color of custom," and to

acts "under law, statute, ordinance, [or]

regulation").

24

any other foreign country; and any

law of any State in conflict with

this provision is hereby declared

null and void.22

The overall structure of the 1870 Act

reveals a carefully crafted congressional

scheme in which some provisions apply

only to state action, some apply only to

state or federal action, and some apply

without limitation to all persons, public

and private.23 The absence of any

express state action requirement in the

first sentence of § 16 reflects a

considered decision to give to that

provision a broader reach then the seven

provisions which do contain such

16 Stat. 144 (emphasis added).

23 Supporters of the 1870 Act

insisted that under § 2 of the Fifteenth

Amendment Congress could prohibit private

as well as government actions interfering

with the right of blacks to vote. Cong.

Globe, 41st Cong., 2d Sess. 3671

(1870)(Sen. Morton).

25

restrictions.24

Respondent correctly notes that the

particular impetus behind the adoption of

§ 16 was concern with mistreatment of

Chinese immigrants, particularly in

California. The tax provision of § 16 was

a direct reaction to California statutes

imposing special taxes on Chinese

immigrants.25 On the other hand, the

language in § 16 extending portions of the

1866 Act to aliens, particularly the

application to them of "the same right ...

to make contracts ... as is enjoyed by

white citizens," was not a reaction to any

discriminatory state action. When the

In addition, § 17 of the 1870

Act, like § 2 of the 1866 Act, imposes

criminal sanctions both on government

officials and on private parties acting

pursuant to custom.

25 See McClain, The Chinese

Struggle for Civil Rights in Nineteenth

Century America: The First Phase. 1850-

1870. 72 Cal. L. Rev. 529 (1984).

26

1870 Act was adopted no California law

limited the right of the Chinese to make

contracts, and we have been unable to

unearth any suggestion that state or

local officials did so.26 Private

discrimination against Chinese workers,

on the other hand, was rampant. Many

private employers refused to hire Chinese

immigrants. The ability of the Chinese

to find work was further curtailed by

organized boycotts of Chinese-made goods,

and of employers who hired Chinese

employees. These boycotts were so

successful that west coast manufacturers

placed on boxes of their goods labels

assuring customers that the contents "are

26 The plaintiff in Yick Wo v.

Hopkins. 118 U.S. 356 (1886), although

operating his laundry since 1862, had

encountered no problems with local

authorities until 1885. 118 U.S.at 358.

27

made by WHITE MEN."2 ̂ "Successful labor

agitation . . . resulted in the firing of

Chinese workers in nearly every urban

industry in which they had thrived....* 28

Read against this background, Senator

Stewart's explanation of § 16 clearly

e n c o m p a s s e s p r i v at e as well as

governmental abuses:

We are inviting to our shores,

or allowing them to come Asiatics.

We have got a treaty allowing them

to come.... We have pledged the

honor of the nation that they may

come and shall be protected. For

twenty years every obligation of

humanity, of justice, and of common

decency toward those people has been

violated by a certain class of men—

bad men I know; but they are

violated in California and on the

Pacific coast. While they are here

I say it is our duty to protect

them. I have incorporated that

* A. Saxton, The Indispensable

Enemy 74 (1971) (emphasis in original

label) .

28 C. Wollenberg, ed., Ethnic

Conflict in California, 96 (1970). We

set forth in Appendix C historical

materials dealing with the treatment of

Chinese immigrants in this era.

28

provision in this bill ... so that

we shall have the whole subject

before us in one discussion. It is

as solemn a duty as can be devolved

upon this Congress to see that those

people are protected, ... to see

that they have the equal protection

of the laws, notwithstanding that

they are aliens. They, or any other

aliens, who may come here are

entitled to that protection. If the

State courts do not give them the

equal protection of the law, if

public sentiment is so inhuman as to

rob them of their ordinary civil

rights, I say I would be less than a

man if I did not insist, and I do

here insist that that provision

shall go on this bill....

Cong. Globe, 41st Cong. 2d Sess. 3658

(1870). Senator Stewart clearly

c o n t e m p l a t e d p r o t e c t i n g Chinese

immigrants, not only from state officials,

but from the whole class of "bad men" who

had so long been mistreating them, to deal

not merely with abuses occurring under

color of law, but with "the whole

subject.

a

29

measure

Although § 16 was referred to as

to assure "equal protection of

(continued...)

29

III. THE 1874 REVISED STATUTES DID NOT

REDUCE THE SUBSTANTIVE PROTECTIONS

OF THE 1866 CIVIL RIGHTS ACT_________

Respondent's argument with regard to

the 1874 Revised Statutes differs from

that o r i g in a l l y advanced by the

dissenting opinion in Runyon. The Runvon

dissent insisted that the actual intent

of Congress in enacting the codification

that includes § 1977 (42 U.S.C. § 1981)

was "beside the point," 427 U.S. at 207-

08, because the meaning of that provision

was controlled by "the Revisers'

unambiguous note before" "Congress when § 29

29 (...continued)

the law," Senator Stewart repeatedly used

this phrase to refer to the protection

afforded by § 16 itself, not simply as a

reference to the failure of state laws to

treat blacks, whites, and asians in a

non-discriminatory manner. Cong. Globe,

41st Cong., 2d Sess. 3658, 3807, 3808.

"Equal protection" was also widely

understood in the nineteenth century to

refer to the duty of states to protect

their residents from abuses by other

private citizens. J. tenBroek, Equal

Justice Under Law (1951).

30

1977 was passed" in 1874. 427 U.S. at

205. R e s p o n d e n t now c o r r e c t l y

acknowledges that the "note" referred to

was not written until 1875. Resp. Rearg.

Br. 39. Respondent insists, however, that

the legislative history of the 1874

Revised Statutes demonstrates that

Congress specifically intended to repeal

the protections against discrimination in

contracts afforded by § 1 of the 1866 Act

(re-enacted as § 18 of the 1870 Voting

Rights Act) , and to codify in § 1977 only

§ 16 of the Voting Rights Act.

Respondent's contention faces three

insurmountable obstacles. First, the

Court has repeatedly insisted that

Congress will not be deemed to have

repealed prior legislation by mere

implication; an intent to repeal will be

found only where Congress has expressed

it in a clear affirmative manner. E.q. .

31

Ruckleshaus v. Monsanto Co.. 467 U.S.

986, 1017 (1984). Second, as we noted at

length in our previous brief, Congress

was repeatedly and expressly reassured

that the 1874 Revised Statutes in

general, and the civil rights provisions

in particular, were not altering the

substantive law as it existed prior to

1874. Pet. Rearg. Br. 10-13. Third,

although the wording of § 1977 is the same

as that of § 16 of the 1870 Act, the

language of § 1977 regarding the right to

contract is also identical to this

provision of § 1 of the 1866 Act.

Congress, having codified in 1874 a

guarantee of the right to contract

identical to the guarantee in § 1 of the

1866 Act, and the sponsors of the

legislation having insisted that the

codification entailed no substantive

changes in the law, the 1874 Revised

32

Statutes, like the codification at issue

in United States v. Kozminski. "most

assuredly was not intended to work a

radical change in the law." 101 L.Ed.2d

788, 807 (1988); cf. District of Columbia

v . Thompson Co.. 346 U.S. 100, 110-18

(1953).30

-3U The side notes described by

respondent as "the Secretary of State's

addition of marginal notations," Resp.

Rearg. Br. 37, were not written by the

Secretary, but by a private publisher,

see 18 Stat. 113, and are thus no more

authoritative than a West Publications

headnote. The passage in Abbott's

National Digest on which respondent

relies was not printed until 1884, a

decade after the passage of the Revised

Code. Abbott's own draft of the revision

was rejected by Congress precisely because

Abbott and the other commissioners had

attempted to make substantive changes in

the law. Pet. Rearg. Br. 8-9. Durant's

heading for § 1977, "Equal Rights Under

The Law," is at best ambiguous, for it

could of course refer to the fact that the

section was a federal law guaranteeing

equal rights.

33

IV. THE DOCTRINES OF CONGRESSIONAL

RATIFICATION AND STARE DECISIS COMPEL

REAFFIRMATION OF THE DECISIONS IN

RUNYON AND JONES______________________

A. RESPONDENT WOULD NULLIFY STARE

DECISIS

We demonstrated in our previous

brief that reaffirmation of Runvon and

Jones is required by the established

principles of stare decisis: these

decisions have benefited, not harmed, the

law and society, have not proved

unworkable,31 have not been effectively

overruled by later decisions, and cannot

be dismissed as clearly or egregiously

ill-reasoned or researched. Respondent

does not dispute these specific

contentions about the nature and impact of

31 It is the overruling of Runvon

or Jones that would produce unworkable and

illogical results, as discussed in Points

I and II above.

34

Jones and Runyon.32 Respondent offers,

instead, a quasi-constitutional argument

against the doctrine of statutory stare

decisis itself.

In respondent's view, when a prior

statutory decision is challenged, the

only question that the Court should

consider is whether or not it now agrees

with that earlier opinion. The Court

must on this view overrule any "erroneous

decision," because a failure to do so

"would be tantamount to legislation by

the judicial branch, in violation of

separation of powers." Resp. Rearg. Br.

95. Under respondent's rule, every

Respondent points out that the

Court has overruled precedents in the

past. However, as shown in Appendix C to

our opening brief and confirmed by recent

scholarly analysis, see W. Eskridge, Jr.,

Overruling Statutory Precedents. 76 Geo.

L. J. 1361, 1369, 1388, 1409 (1988), these

d e c i s i o n s were based on special

justifications, not simply a conclusion

that the precedent was wrongly decided.

35

mistaken construction of a federal law

w o u l d be an i n v a s i o n of the

constitutional prerogatives of Congress;

the sole responsibility of the Court

would be to consider de novo whether its

prior decisions were correct. A new

interpretation of the law would have to

be issued whenever a majority of the

Court believed that it had detected an

error.

Limiting stare decisis in the way

suggested by respondent would, of course,

completely nullify the doctrine of stare

decisis in the statutory context; after

all, no one has suggested that the Court

should overrule correctly decided

statutory precedents. Contrary to

respondent's novel separation of powers

theory, the Court has long held that the

doctrine of stare decisis has strongest

force in the area of statutoryin the area

36

construction.

The rule advocated by respondent

necessarily would require an extensive,

periodic "reconsideration" process,

imposing massive costs on the Court and

l it ig an ts . If the Court were

systematically to revisit close questions

of statutory construction — a task which

in respondent's view is essential to

assure fidelity to the separation of

powers — it would be able to produce

little else.33

The circumstances of this case

illustrate the magnitude of the change in

stare d ecisis law sugg es te d by

respondent. Although noting decisions

suggesting that stare decisis might not

33 Most questions resolved by the

Court are close, as shown by the large

number of dissenting opinions. In the

1986 Term, almost 75% of the cases

decided with full opinions included a

dissent. Supreme Court 1986 Term, The

Statistics, 101 Harv. L. Rev. 362, 364 (1987).

37

save a prior decision whose erroneous

nature was particularly "blatant" or

"beyond doubt," Resp. Rearg. Br. 101-02,

respondent does not suggest that Jones.

Runyon and their progeny meet that

standard. To the contrary, Justice

Harlan's dissenting opinion in Jones

stopped short of asserting that the

majority was wrong, stating only that "a

contrary conclusion may equally well be

drawn." 392 U.S. at 454 (Harlan, J. ,

joined by White, J. , dissenting).34 If,

on balance, Justice Harlan felt that Jones

was mistaken, he regarded the matter as

presenting the sort of close case to

which stare decisis should be applied.

See Monroe v. Pape. 365 U.S. 167, 192

34 Justice Harlan also concluded

that the Court's construction "at least is

open to serious doubt," 392 U.S. at 450,

and that "there is an inherent ambiguity

in the term 'right' as used in § 1982,"

id. at 452-53.

-I*

38

(1961) (Harlan, J., concurring and

dissenting) (stare decisis applicable

unless error in prior decision "appears

beyond doubt").

B. CONGRESS APPROVED JONES AND

RUNYON

Respondent argues that the extensive

legislative history indicating Congress'

explicit approval of Jones and its progeny

is irrelevant and that no conclusion can

be drawn from Congress' failure to

overturn these cases. However, this is

not a case of unexplained Congressional

f a i l u r e to o v e r t u r n a C o u r t

interpretation. Without repeating the

extensive legislative history, two points

are worth noting. First, Congress in 1972

was not silent; rather the proponents of

Title VII explained in detail why the §

1981 remedy should be retained and the

subsequent vote can only be interpreted as

agreement with those explanations.

39

Second, this is not a case of

Congressional inaction. In passing the

Civil Rights Attorney's Fees Act of 1976,

Congress in effect amended § 1981 itself.

The Fees Act lists §§ 1981 and 1982 by

name.* 35 * The result is the same as if the

fees provision had been placed directly

into §§ 1981 and 1982. This type of

explicit Congressional action. taken after

the Jones. Runyon and McDonald35 had been

decided and with knowledge of those

decisions, is entitled to great weight.

C. CONGRESS AND NOT THE COURT IS

C O M P E T E N T TO ADDRESS THE

INTERACTION OF TITLE VII AND

§ 1981

Respondent and several amici urge

that Congress erred when it decided not

to make Title VII the exclusive remedy

35 See 42 U.S.C. § 1988 (1982).

35McDonald v. Santa Re Trail Transp.

Co., 427 U.S. 273 (1976)(cited with

approval in H.R. Rep. No. 1558, 94th

Cong., 2d Sess. 4 (1976)).

40

for e m p l o y m e n t d i s c r i m i n a t i o n .

Respondent asserts that opposition to the

1971 Hruska amendment was based on a

"gross misapprehension," Resp. Rearg.

Br. 122 n. 99, and amicus Washington

Legal Foundation complains that the

amendment was defeated because of an

"erroneous statement"37 on the floor of

the Senate. Amicus EEAC characterizes

the d e b a t e s in 1972 as "fairly

perfunctory."38

The EEAC also makes a number of

specific factual assertions about the

manner in which § 1981 and Title VII have

interrelated over the last twenty years,

including allegations that § 1981 has

generally "drive[n] the use of Title VII

37 B r i e f A m i c u s Curiae of

Washington Legal Foundation at 27.

38 Brief Amicus Curiae of Equal

Employment Advisory Council at 18; see

also id. at 16 (no "reasoned policy

decision").

41

' out of currency'" and that complainants

"often" use the greater remedies available

under § 1981 "to extract from defendants

settlements that bear little relationship

to the degree of damages suffered." EEAC

Br. at 7, 11.39

These arguments have nothing to do

with Runvon. which involved private school

a d m i s s i o n s and not e m p l o y m e n t

discrimination. And, as we noted in our

The E E A C makes further

inconsistent factual assertions: that

complainants do not file Title VII claims

or charges at all, relying instead solely

on § 1981, EEAC Br. 7, 22; that

complainants do file Title VII charges,

but then file premature § 1981 claims in

federal court, thus impeding EEOC's

investigatory and conciliation function,

id.. at 19-23? that complainants have

"common[ly]" filed Title VII charges and

deliberately postponed filing a § 1981

claim until the EEOC has finished its

work, thus unfairly obtaining the

information unearthed by the EEOC

investigation, id. at 12-13; and that §

1981 is of no importance to complainants

because Title VII by itself "insur[es]

that the private claimant will receive

the most complete relief possible," .id.

at 24 .

42

earlier brief, there are a large number of

cases such as Runyon. which, because of

their subject matter, could not have been

brought under other federal laws. Pet.

Rearg. Br. 109-112. Title VII itself

applies only to employers with 15 or more

employees, thus excluding some 10 million

workers and 86 percent of all employers.

Apparently the arguments concerning

Title VII are directed toward obtaining

the partial repeal of § 1981 that

Congress refused to enact in 1972. Such

arguments are properly addressed to

Congress, not this Court. Moreover, the

hypothetical problems asserted by the EEAC

were explicitly raised and addressed by

Congress when it amended Title VII in

1972. For example, Congress knew that an

employee could "completely bypass both the

T. Eisenberg & S. Schwab, The

Importance of Section 1981. 73 Cornell L.

Rev. 596, 602 (1988) .

43

EEOC and the NLRB and file a complaint in

Federal court" under § 1981. 118 Cong.

Rec. 3173 (1972).

In addition, the EEAC offers no

authority for its assertions regarding

what actually has occurred over the years

since Jones. A significant body of

evidence indicates that these assertions

are incorrect. One recent study disclosed

that virtually all § 1981 employment

complaints also alleged a cause of action

under Title VII, indicating that most

plaintiffs are not using § 1981 to bypass

Title VII.41 The existence of serious

problems with the effectiveness of the

EEOC investigation and conciliation

41 Eisenberg & Schwab, 73 Cornell

L. Rev. at 603. This study also showed

that § 1981 plaintiffs are successful

about as often as Title VII plaintiffs and

that the rate of monetary settlements are

lower than in Title VII cases, id. at

600, thus casting doubt on the assertion

that plaintiffs have been able to extract

unfair or unreasonable settlements.

44

process also undermines the argument that

Congress intended to force § 1981

plaintiffs into this overburdened

system.42

A recent report indicates that

the EEOC found reasonable cause to

believe that discrimination occurred in

only 3% of the charges it processed in

1986. Office of Program Operations,

EEOC, Annual Report F.Y. 1986. While

receiving 68,822 charges in FY 1986, the

EEOC filed only 526 cases in federal

court, of which 99 were subpoena

enforcement. Id. at 16, 17. A 1987

Government Accounting Office investigation

of the Birmingham office of the EEOC

showed that 29% of the charges received

inadequate investigation and that none of

these charges was decided in favor of the

charging party. EEOC Birmingham Office

Closed Discrimination Charges Without Full

Investigation. GAO Report, July, 1987.

See also Staff of the House Comm. on

Educ. & Labor, 99th Cong., 2d Sess.,

Investigation of Civil Rights Enforcement

By the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission (Comm. Print 1986) , at VII

("greater emphasis on the rapid closure

of cases at the expense of quality

investigations").

45

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, the Court

should reaffirm the holdinq in Runvon.

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON*

RONALD L. ELLIS

ERIC SCHNAPPER

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

PENDA D. HAIR

Suite 301

1275 K. Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

HAROLD L. KENNEDY, III

HARVEY L. KENNEDY

Kennedy, Kennedy, Kennedy

and Kennedy

701 First Union Building

Winston-Salem, N.C. 27101

(919) 724-9207

Attorneys for Petitioner

♦Counsel of Record

S 33 IGN 3 d d V

Appendix A

J. James, The Framing of the

Fourteenth Amendment (1956)

___________(Pp . 52-53 )_______

"By the time that Congress

adjourned for the Christmas holidays,

people were reading [the Schurz Report]

in their newspapers. This long analysis

and supporting documents had been sent to

Congress along with the short Grant

report in response to Sumner's resolution

formally asking for it. Radicals had no

intention of running the risk that such

an important propaganda document might be

buried in executive files.

"As was expected, the document

created much excitement.... [T]he

Chicago Tribune's characterization of

the Schurz report as the 'ablest, most

2a

thorough and exhaustive study yet made'

is representative of the Radical position

.... [T]he document was published in

full in many newspapers, thus reaching

and influencing many voters the country

over. Copies were printed and circulated

by authority of Congress and added to the

mass effect of the Schurz document.

According to its author, the President

came to consider sending him South his

greatest mistake up to late January."

3a

Appendix B

Black Code Provisions Regarding

_____ Testimony By Freedmen_____

Ten of the former confederate states

adopted laws expressly permitting blacks

to testify in any case in which a black

had an interest. Alabama Laws 1866, p.

98 (black can testify if black a party or

crime victim); Arkansas Laws 1866-67, p.

98 (no limitations on testimony by

blacks); Florida Const'n. 1865, art. xvi,

sec. 2; Florida Laws 1865-66, pp. 35-36,

145 (black can testify if black a party

or crime victim); Georgia Laws 1865-66,

pp. 239-40 (black can testify if black a

party or crime victim); Mississippi Laws

1865, p. 82 et seq. (black can testify in

open court if black a party or crime

victim); North Carolina Laws 1865, p. 102

(black can testify if black a party or

4a

crime victim; not in other cases except

with consent of the parties); South

Carolina Laws 1864-65, p. 286 (black can

testify in any civil or criminal cases

"which affects the person or property" of

a black); Tennessee Laws 1865-66, p. 24

(no limitations on testimony by blacks) ;

Texas Const'n, 1866, Art. viii, sec. 2,

Tex. Laws 1866, p. 27 (blacks shall not

be prohibited from testifying, on account

of race, in any civil or criminal case

"involving the right of, injury to, or

crime against" a black); Laws of Virginia

1865-66, p. 89 (black can testify in any

case in which a black is a party or a

crime victim, or allegedly committed a

crime in conjunction with a white).

5a

Appendix C

Sources Regarding Treatment

Of Chinese in the West

P. Chiu, Chinese Labor in

California, 1850-1880, An Economic Study,

12-19 (Chinese workers expelled from

mining camps at behest of white miners),

63 (different pay scales for Chinese and

white laborers), 87 (systematic replace

ment of Chinese agricultural workers with

whites), 91-92 (labor opposition to

employment of Chinese in woolen mills,

leading to "[m]ajor reductions" in

Chinese employment in the industry), 92

(different pay scales for Chinese and

w h i t e w o r k e r s ) , 95 ( c l o t h i n g

manufacturers opposed to hiring Chinese

out of fear they would use their skills,

once learned, to start their own

businesses), 106 (shoe manufacturers

opposed for a similar reason to hiring

6a

Chinese) , 115 (different pay scales for

whites and Chinese in shoe industry), 126

(labor union successful campaign to

remove Chinese workers from the cigar

manufacturing industry), 129-38 (economic

views of unions and others opposed to the

employment of Chinese workers)(1967).

I. Cross, A History of the Labor

Movement in California 78-80 (boycotts

of employers hiring Chinese; 1859

resolution of California People's

Protective Union pledged "That every

member of the People's Protective Union

will hereafter wherever he finds Chinese

employed, refuse to patronize such

employers; and further that the People's

Protective Union recommends every friend

of White labor throughout the State to

pursue a similar course") (1935).

S. Lyman, Chinese Americans 59-61

(expulsion of Chinese from mining

7a

camps) (1974) .

A. Rolle, California: A History 288

(mines refused to hire Chinese) (4th ed.

1963) .

A. Saxton, The Indispensible Enemy,

Labor and the Anti-Chinese Movement in

California 3 (expulsion of Chinese from

mining camps), 57 (same), 72-79 (general

history of "anti-coolie clubs" in

California; successful primary boycotts

of Chinese made goods, secondary boycotts

of merchants selling such goods;

consequent introduction of product labels

stating goods were "made by WHITE

MEN") (1971) .

C. Wollenberg, ed., Ethnic Conflict

in California History 72-74 (Chinese

workers excluded from mining camps), 94-

95 (attacks on Chinese workers in

California and Nevada), 96 ("Even though

much of California's anti-Chinese

8a

l e g i s l a t i o n w a s d e c l a r e d

unconstitutional, its intent was realized

by successful labor agitation which

resulted in the firing of Chinese workers

in nearly every urban industry in which

they had thrived ...") (1970).

Daily Alta (San Francisco), February

13, 1867 (white rioters attacked

officials of a contractor because it

hired Chinese workers).

Daily Alta, February 14, 1867 (riot

of previous day condemned as violation

"the spirit of [the] treaty" with China).

Daily Alta, February 20, 1867 (plans

for a general strike in San Francisco

"for ... the driving out of employment of

all the Chinese in the city").

Daily Alta, February 21, 1867

(meeting of laborers and others resolved

"That we will not patronize any merchant,

manufacturer, contractor, capitalist,

9a

lawyer, doctor, brewer, or any person who

in anywise employ Chinese labor.").

Daily Alta, February 22, 1867, p.l,

col. 1 (the "anti-Chinese labor movement"

criticized for refusing to patronize the

Chinese "washerman, . . . house servant,

... gardener, ... vine dresser, ... cigar

maker ... and dirt shoveller [sic]").

Daily Alta, March 10, 1867 (At

m e e t i n g of District Anti-Coolie

Association "[a] pledge was read to the

effect that those present would not buy

any goods manufactured by Chinamen").

Sacramento Daily Union, September

18, 1869, p.l, col.6 (describing opposi

tion among working men in Nevada to

employment of Chinese).