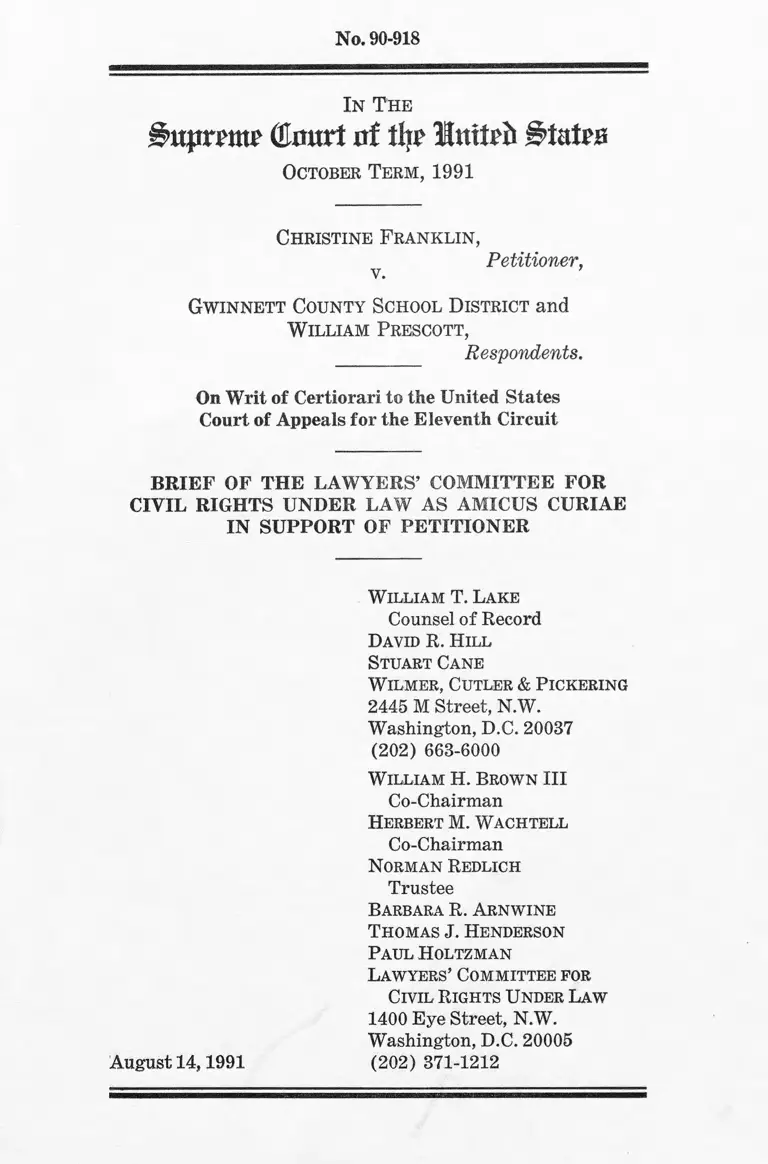

Franklin v. Gwinnett County School District Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

August 14, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Franklin v. Gwinnett County School District Brief Amicus Curiae, 1991. 68c83153-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/42cb7ed0-e9c8-4bf6-a044-afca152e2899/franklin-v-gwinnett-county-school-district-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

I n T h e

^upnmu' (Court of tip llnttrfr States

October Term , 1991

Christine F ra n k lin ,

Petitioner,v.

Gw in n ett County School District and

W illiam Prescott,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

BRIEF OF THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

William T. Lake

Counsel of Record

David R. H ill

Stuart Cane

Wilmer, Cutler & P ickering

2445 M Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20037

(202) 663-6000

William H. Brown III

Co-Chairman

Herbert M. Wachtell

Co-Chairman

Norman Redlich

Trustee

Barbara R. Arnwine

Thomas J. Henderson

Paul H oltzman

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212August 14,1991

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether a private party may recover compensatory

damages for an intentional violation of Title IX of the

Education Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C. 1681 et seq.

0)

QUESTION PRESENTED ___ i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES... ........................... ......... iv

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE............................... 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ....... ................... ........... 2

ARGUMENT.......................... 4

I. UNDER THE LAW AS STATED IN BELL v.

HOOD, COMPENSATORY DAMAGES ARE

AVAILABLE TO A PRIVATE PLAINTIFF

WHO PROVES AN INTENTIONAL VIOLA

TION OF TITLE IX .................................... ....... 5

II. THERE ARE NO ELEVENTH AMENDMENT

OR OTHER CONSTITUTIONAL CONCERNS

THAT WARRANT RESTRICTION OF THE

REMEDIES AVAILABLE UNDER TITLE IX.. 14

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

CONCLUSION 24

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36

(1974)............................................................. ........ 13

Atascadero State Hospital v. Scanlon, 473 U.S. 234

(1985)...... ............ .................................................. 20, 21

Bell v. Hood, 327 U.S. 678 (1946).... ....... ......... ..... passim

Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of the Fed

eral Bureau of Narcotics, 403 U.S. 388 (1971) ..5, 6, 7, 8

Board of County Commissioners v. United States,

308 U.S. 343 (1939)... 6

Bush v. Lucas, 462 U.S. 367 (1983)............... ..... 11

Butz v. Economou, 438 U.S. 478 (1978)__ ______ 8

Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677

(1979) ........ passim

Carlson v. Green, 446 U.S. 14 (1980) __.,_______ 9

The Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883) ............. 18

Consolidated Rail Corp. v. Darrone, 465 U.S. 624

(1984) ...... passim

Cort v. Ash, 422 U.S. 66 (1975)............ ............ .. .7,10,11

Davis v. Passman, 442 U.S. 228 (1979)................. passim

Deckert v. Independence Shares Corp., 311 U.S.

282 (1940) ...... 6

Drayden v. Needville Independent School District,

642 F.2d 129 (5th Cir. 1981) ....... ........ ....... ...... . 15

Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974) ............... 16, 22

Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445 (1976)______ 19

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S.

747 (1976) .................. 13

Grove City College v. Bell, 465 U.S. 555 (1984).... 2

Guardians Association v. Civil Service Commission

of New York, 463 U.S. 582 (1983)........ ..... ..... ..passim

Hayes v. Michigan Central Railroad Co., I l l U.S.

228 (1884)............... ....... ....................... ............ - 5

International Union of Electrical, Radio & Machine

Workers v. Robbins & Myers, Inc., 429 U.S. 229

(1976) ... .... ...... .. ........ ... ... ............ ........ ........... 13

J.I. Case Co. v. Borak, 377 U.S. 426 (1964)............ 6

Jett v. Dallas Independent School District, 491 U.S.

701 (1989).............. ........................... ............... . 8

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S.

454 (1975).............. ................. ............... ............. 13,14

V

Lieberman v. University of Chicago, 660 F.2d 1185

(7th Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 456 U.S. 937

(1982).... ...... ....... ................... .............................. 17

Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137

(1803) .............. ....... .......... ..... ............... ............. . 5

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973) ....................... ....... ............... ..................... 13

North Haven Board of Education v. Bell, 456 U.S.

512 (1982) ................................... ........ ........ ....... 4, 13

Padway v. Patches, 665 F.2d 965 (9th Cir. 1982).. 12

Pearson v. Western Electric Co., 542 F.2d 1150

(10th Cir. 1976) ....................................... ........... 12

Pennhurst State School & Hospital v. Halderman,

451 U.S. 1 (1981) ______________ ____ ____ ..passim

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978)............... ....... .......... ....... . 18

Rosado v. Wyman, 397 U.S. 397 (1970) ............... 16, 21

Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez, 436 U.S. 49

(1978) ........ ......... .................................... .............. 7

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville Railroad Co., 323

U.S. 192 (1944) ................. ............... ........... ....... 6

Steward Machine Co. v. Davis, 301 U.S. 548

(1937)............................. ...... ................................. 15

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229

(1969) ...... ........... ................ .................................. 5, 6, 7

Texas & New Orleans Railroad Co. v. Brotherhood

of Railway & Steamship Clerks, 281 U.S. 548

(1930) ............ ..................................... ....... .......... . 6

Texas & Pacific Railway v. Rigsby, 241 U.S. 33

(1916).............. ........... ............................. ..... ....... 6

Transamerica Mortgage Advisors, Inc. v. Lewis,

444 U.S. 11 (1979) ............. ..... ................. .......... passim

United States Department of Transportation v.

Paralyzed Veterans of America, 411 U.S. 597

(1986) ___________ _________ ___ ___ ___ _ 4

United States v. Menasch, 348 U.S. 528 (1955)... 21

United States v. Republic Steel Corp., 362 U.S. 482

(1960) .......................... ............... ....... ............... ... 6,11

Welch v. Texas Department of Highways & Public

Transportation, 483 U.S. 468 (1987) ......... ...... . 14

Wicker v. Hoppock, 73 U.S. (6 Wall.) 94 (1867).... 5

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

VI

Wyandotte Transportation Co. v. United States,

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

389 U.S. 191 (1967) _________ ______ __„.....6, 7,10

Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908)........... ......... 22

CONSTITUTION AND STATUTES

U.S. Const, amend. X I____ ______ _____ ______ 14,19, 21

U.S. Const, amend. X IV ....... ..... ....................... ....... 18

U.S. Const, art. I, § 8, cl. 1 (Spending Clause) ......15,17,18

42 U.S.C. § 1981........... ........ ....................... ............... 14

42 U.S.C. § 6101 et seq........... .................... ............... 20

Civil Rights Act of 1964, tit. VI, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d

et seq ........ ........................ .......... ........... ......... ..... ..passim

Civil Rights Act of 1964, tit. VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e

et seq._____________ ___ ___ ___________ _12,13, 14

Civil Rights Remedies Equalization Act of 1986,

42 U.S.C. § 2000d-7..... ......................... ........... .......................................passim

Education Amendments of 1972, tit. IX, 20 U.S.C.

§ 1681 et seq__________ _______ ______ ___ .....passim

Rehabilitation Act of 1973, § 504 (as amended), 29

U.S.C. § 794................. ................... ..... ..... ....... ... 4, 20, 21

OTHER LEGISLATIVE MATERIALS

110 Cong. Rec. 1527 (1964)............. 18

110 Cong. Rec. 1529 (1964) ................... 18

110 Cong. Rec. 1540 (1964)__ 9

110 Cong. Rec. 5256 (1964)... ... ....................... 11

110 Cong. Rec. 7062 (1964) ....... 9

110 Cong. Rec. 13,333 (1964).......... ......... ............ . 18

117 Cong. Rec. 39,252 (1971)........................... -....... 9

118 Cong. Rec. 5806-07 (1972)....... ...................... ... 9

132 Cong. Rec. 28,094-95 (1986) -------- -------------- 22

132 Cong. Rec. 28,623 (1986).................................... 22, 23

H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 955, 99th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1986) ...... ............ .......... ........................—-....... 22

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963)....... 18

S. Rep. No. 388, 99th Cong., 2d Sess. (1986)---- ---- 21, 22

MISCELLANEOUS

2A N.J. Singer, Sutherland Statutory Construction

(4th ed. 1984) ...... ................... ....... ............ -......... 21

Note, The Eleventh Amendment and State Damage

Liability Under the Rehabilitation Act of 1973,

71 Va. L. Rev. 655 (1985) .................................... 18

In The

B n p t m t (C iw r i u f % B U U b

October Term , 1991

No. 90-918

Christine F ra n k lin ,

Petitioner, v. ’

Gw in n ett County School District and

W illiam P rescott,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

BRIEF OF THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

This amicus curiae brief is submitted by the Lawyers’

Committee for Civil Rights Under Law in support of peti

tioner Christine Franklin. Ety letters filed with the Clerk,

petitioner and respondents have consented to the filing of

this brief.

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers’ Committee is a nonprofit organization

established in 1963 at the request of the President of the

United States to involve leading members of the bar in

the effort to ensure civil rights for all Americans. As

part of this effort, the Lawyers’ Committee has partici

pated as amicus curiae in two previous Title IX cases

before this Court, Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441

2

U.S. 677 (1979) and Grove City College v. Bell, 465 IJ.S.

555 (1984). It also has represented parties or partici

pated as amicus curiae in numerous cases arising under

other federal antidiscrimination laws and under the

Constitution.

This case raises an important issue concerning the

relief available under Title IX, and the Court’s decision

may also affect the remedies available under Title VI of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964—which served as the model

for Title IX. Because the Lawyers’ Committee frequently

represents victims of race discrimination in litigation

under Title VI, it has a particular interest in urging

principles that will result in the sound application of

Title VI, and in the resolution of any uncertainty as to

whether the federal courts may provide full relief to vic

tims of intentional race discrimination in federally as

sisted programs,

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This case concerns a core judicial function'—the award

of remedies to implement a federal statutory cause of ac

tion. Petitioner has an unquestioned right under Title IX

of the Education Amendments of 1972 to be free from

sex-based discrimination in a federally assisted educa

tional program. She has an equally unquestioned right

to sue to redress an intentional violation of that right.

The issue presented is whether the federal courts are dis

abled from providing compensatory damages as a means

of such redress.

The federal courts have power to provide the relief

requested. Nothing in the text of Title IX, its legislative

history, or its animating purposes suggests that the

courts have been denied that power. No circumstances

exist here to displace the usual rule that all available

remedies may be employed to vindicate federal rights,

Bellv. Hood, 327 U.S. 678, 684 (1946). Indeed, that rule

3

applies with particular force where, as in this case, the

choice is “damages or nothing.”

Just as nothing in Title IX or its legislative history

restricts the federal courts’ familiar remedial powers,

nothing in the Eleventh Amendment or principles derived

from it requires that compensatory damages be withheld

for intentional violations of Title IX. In Pennhurst

State School & Hosp. v. Halderman, 451 U.S. 1 (1981),

this Court held that Congress must speak clearly when

it seeks to create rights that are enforceable against the

States. And in Guardians Ass’n v. Civil Service Comm’n

of Neiv York, 463 U.S. 582 (1983), two members of the

Court found Pennhurst to support the denial of retroac

tive relief in an action against a public entity other than

a State, where unintentional discrimination was alleged.

Pennhurst is satisfied here. Title IX speaks clearly

and unambiguously; it creates enforceable rights, not a

mere “nudge in the preferred direction.” Having ac

cepted an obligation not to discriminate, and having will

fully violated that obligation, a recipient of federal funds

should make good the injury done. Any doubt that Elev

enth Amendment principles allow an award of damages

against a public entity in these circumstances was ex

plicitly removed by Congress when, in 1986, it reaffirmed

the federal courts’ authority to provide “remedies both at

law and in equity” in Title IX actions against the

States. 42 U.S.C. § 2000d-7 (1988).

4

ARGUMENT

Petitioner has alleged that she suffered intentional dis

crimination on the basis of sex at the hands of Respond

ents, in violation of Title IX of the Education Amend

ments of 1972, 20 U.S.C. § 1681 (1988). This case pre

sents the question whether, if she proves her case, she

may recover compensatory damages.1 Congress did not

expressly create a private cause of action when it enacted

Title IX, and did not express a preference that certain

forms of individual relief be available or unavailable.

Congress did, however, establish an enforceable right for

the benefit and protection of a defined class; and this

Court has held that the statute therefore gives an im

plied cause of action to an injured member of that class.

Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677, 689, 717

(1979). This Court routinely has held that, where such

a federal right has been invaded and a cause of action

exists, “federal courts may use any available remedy to

make good the wrong done.” Bell v. Hood, 327 U.S. 678,

684 (1946).

1 References in the brief generally will be only to Title IX, the

statute under which this case arises. This Court, however, has

construed the remedial provisions of Title IX, Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d et seq. (1988), and Section

504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, as amended, 29 U.S.C.

§794 (1988) to be related. See Cannon v. University of Chicago,

441 U.S. 677, 694-96 (1979) ; United States Dep’t of Transp. v.

Paralyzed Veterans of Am., 477 U.S. 597, 600 n.4 (1986) ; Consoli

dated Rail Corp. v. Darrone, 465 U.S. 624, 626, 630 & n.9 (1984) ;

North Haven Bd. of Educ. v. Bell, 456 U.S. 512, 529 (1982). Thus,

whether compensatory damages are available under Title IX may

bear strongly on whether such damages are available under Title VI

and Section 504. In addition, cases construing either Title VI or

Section 504 aid in the interpretation of Title IX.

I. UNDER THE LAW AS STATED IN BELL v. HOOD,

COMPENSATORY DAMAGES ARE AVAILABLE TO

A PRIVATE PLAINTIFF WHO PROVES AN IN

TENTIONAL VIOLATION OF TITLE IX.

Long ago, this Court held that, “where legal rights

have been invaded, and a federal statute provides for a

general right to sue for such invasion, federal courts may

use any available remedy to make good the wrong done.”

Bell v. Hood, 327 U.S. 678, 684 (1946) (footnote

omitted); see Davis v. Passman, 442 U.S. 228, 245-47

(1979) ; Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of the

Federal Bureau of Narcotics, 403 U.S. 388, 396 (1971) ;

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229, 239-

40 (1969). The rule of Bell v. Hood is grounded in the

bedrock principle that, where federally protected rights

have been invaded, a federal court may give an appro

priate decree or award that will make the plaintiff whole.

See Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137, 163

(1803) (unless there are particular factors that “exclude

the injured party from legal redress,” the court will apply

the “ ‘general and indisputable rule, that where there is

a legal right, there is also a legal remedy by suit, or

action at law, whenever that right is invaded.’ ” ) (cita

tion omitted) .2

Bell v. Hood concerned the remedies available to a

plaintiff who sued for violations of his Fourth and Fifth

Amendment rights. 327 U.S. at 679. Thus, the rule

taken from that case arose in the context of constitu

tional causes of action. However, prior to Bell v. Hood,

the same rule had been applied in a statutory context.

2 See also Hayes v. Michigan Cent. R.R., 111 U.S. 228, 239-40

(1884) (when a person is injured due to the breach of a statutory

obligation, the person “is entitled to his individual compensation,

and to an action for its recovery”) ; Wicker v. Hop-pock, 73 U.S.

(6 Wall.) 94, 99 (1867) (“The injured party is to be placed, as

near as may be, in the situation he would have occupied if the wrong

had not been committed.” ).

6

See, e.g., Texas & Pac. Ry. v. Rigsby, 241 U.S. 33, 39

(1916).3 Since Bell v. Hood was decided, it has been

applied to constitutional causes of action, see, e.g., Davis,

442 U.S. at 245; Bivens, 403 U.S. at 396-97; and to stat

utory causes of action, see, e.g., Sullivan, 396 U.S. at

239-40; Wyandotte Transp. Co. v. United States, 389

U.S. 191, 200-204 (1967) ; J.I. Case Co. v. Borak, 377

U.S. 426, 433 (1964) ; United States v. Republic Steel

Corp., 362 U.S. 482, 492 (1960). In fact, Bell v. Hood

has been recognized as the “usual rule” for determining

the relief to which an aggrieved party is entitled. Guar

dians Ass’n v. Civil Service Comm’n of New York, 463

U.S. 582, 595 (1983) (opinion of White, J .) .

The Court has recognized only one exception to the

Bell v. Hood rule: Remedies available to an aggrieved

plaintiff may be restricted when Congress has made clear

that particular remedies may not be awarded. Guardians,

463 U.S. at 595 (opinion of White, J . ) ; Davis, 442 U.S.

at 246-47 (plaintiff entitled to recover compensatory

damages because there is no “explicit” congressional dec

laration that this remedy is not available) ; Wyandotte

Transp., 389 U.S. at 200-204; see Transamerica Mort

gage Advisors, Inc. v. Leivis, 444 U.S. 11, 20 (1979)

(“Even settled rules of statutory construction could yield,

of course, to persuasive evidence of a contrary legislative

intent.” ). As these cases stress, affirmative congressional

intent to deny a particular remedy must be shown before

the Bell v. Hood rule is displaced. See Wyandotte

Transp., 389 U.S. at 199-204.4

3 See also Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R.R., 323 U.S. 192, 207

(1944); Deckert v. Independence Shares Corp., 311 U.S. 282, 288

(1940); Board, of County Comm’rs v. United States, 308 U.S. 343,

350 (1939); Texas & New Orleans R.R. v. Brotherhood of Ry. &

S.S. Clerks, 281 U.S. 548, 569-70 (1930).

4 Cf. Cannon, 441 U.S. at 694 (in context of determining whether

implied private right of action exists, “ ‘it is not necessary to show

an intention to create a private cause of action, although an explicit

7

The Bell v. Hood rule applies to this case, and man

dates that compensatory damages be available in Title

IX cases involving intentional discrimination. First,

Petitioner’s complaint invokes federally protected rights.

One of the primary objectives of Title IX was to “provide

individual citizens effective protection against” sex dis

crimination. Cannon, 441 U.S. at 704; see also id. at 694

(“Title IX explicitly confers a benefit on persons discrim

inated against on the basis of sex” ). Second, private

suits may be brought for violations of these rights. Id.

at 689, 717. The only question remaining in this case is

whether compensatory damages are available to one who

proves an intentional violation of Title IX.5 Bell v. Hood

answers that “federal courts may use any available rem

edy to make good the wrong done.” 327 U.S. at 684;

see also Guardians, 463 U.S. at 624-25 (Marshall, J.,

dissenting) ; Sullivan, 396 U.S. at 239-40; Wyandotte

Transp., 389 U.S. at 200-204; see Davis, 442 U.S. at 239

(“ [T]he question whether a litigant has a ‘cause of ac

tion’ is analytically distinct and prior to the question of

what relief, if any, a litigant may be entitled to re

ceive.” ).

Under Bell v. Hood, unless Respondents can show a

clearly stated legislative intent to the contrary, a federal

court may award any appropriate remedy that vindi

cates the federal rights being asserted. See Bivens, 403

U.S. at 396; Transamerica Mortgage, 444 U.S. at 30

(White, J., dissenting) (“in the absence of any contrary

purpose to deny such a cause of action would be controlling’ ”) (em

phasis in original) (quoting Cort v. Ash, 422 U.S. 66, 82 (1975));

Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez, 436 U.S. 49, 79 (1978) (White, J.,

dissenting).

5 In Guardians, “a majority of the Court expressed the view that

a private plaintiff under Title VI could recover backpay.” Darrone,

465 U.S. at 630. A majority of the Guardians Court also “agreed

that retroactive relief is available to private plaintiffs for all dis

crimination, whether intentional or unintentional, that is actionable

under Title VI.” Id. at 630 n.9.

8

indication by Congress, courts may provide private liti

gants exercising implied rights of action whatever relief

is consistent with the congressional purpose,” and they

“need not be restricted to equitable relief” ). Because

there is nothing in Title IX or in the legislative history

surrounding its enactment that shows an explicit con

gressional intent to deny compensatory damages to vic

tims of intentional discrimination in violation of Title

IX, the rule of Bell v. Hood controls. See Guardians, 463

U.S. at 595 (opinion of White, J.) ; Cannon, 441 U.S. at

694; Bivens, 403 U.S. at 397; Transamerica Mortgage,

444 U.S. at 30 (White, J., dissenting).6

Especially strong indications of congressional intent

to deny victims of intentional discrimination a damages

remedy must be shown before the Court departs from

the usual rule of Bell v. Hood. Compensatory damages

are the normal remedy associated with violations of an

individual’s federally protected rights. See Davis, 442

U.S. at 245 (damages are normal remedy to redress viola

tions of liberty interest) ; see also Jett v. Dallas Indep.

School Dish, 492 U.S. 701, 742 (1989) (Brennan, J., dis

senting) ; Bivens, 403 U.S. at 410 (Harlan, J., concurring

in the judgment). Injunctive or declaratory remedies of

ten provide victims with little or no redress against those

who have intentionally violated their rights. See Trans

america Mortgage, 444 U.S. at 35 (White, J., dissenting)

(without damages remedy, victims “have little hope of

obtaining redress for their injuries” ) ; Butz v. Economou,

6 The absence of legislative history showing that Congress wished

to deny victims of intentional discrimination a damages remedy is

not surprising, since the statute itself indicates no such intent.

As this Court noted when considering whether Title IX created a

private right of action, “the legislative history of a statute that does

not expressly create or deny a private remedy will typically be

equally silent or ambiguous” on that same subject. Cannon, 441 U.S.

at 694; see also Transamerica Mortgage, 444 U.S. at 18.

9

438 U.S. 478, 504 (1978) (“Injunctive or declaratory re

lief is useless to a person who has already been in

jured.” ). Respondents can show no clearly expressed con

gressional intent to deny victims of intentional discrim

ination their normal and most effective remedy—com

pensatory damages.

As the normal remedy for intentional discrimination,

compensatory damages unquestionably promote the ob

jectives of Title IX. The Court should reject the United

States’ argument to the contrary. Cf. Brief for the

United States as Amicus Curiae in Support of the Peti

tion for Writ of Certiorari at 18-19. The prohibitions of

discrimination contained in Titles IX and VI focus di

rectly on eliminating discrimination in programs that

receive federal funds. Cannon, 441 U.S. at 704; see also

110 Cong. Rec. 7062 (1964) (Title VI; comments of Sen.

Pastore) ; id. at 1540 (Title VI; comments of Rep. Lind

say) ; 117 Cong. Rec. 39,252 (1971) (Title IX; comments

of Rep. Mink) ; 118 Cong. Rec. 5806-07 (1972) (Title IX;

comments of Sen. Bayh). By arguing that the overriding

purpose of Title IX was to fund educational institutions,

the United States confuses the purpose of Title IX with

the purposes of the appropriations acts that fund particu

lar federal programs. Those are obviously two different

questions. The purpose of Title IX was to eliminate the

use of federal funds to support discriminatory practices

and to provide citizens with effective protection against

those practices. Cannon, 441 U.S. at 704. A compensa

tory damages remedy only furthers this purpose by de

terring intentional violators from accepting federal funds

and by making victims whole if intentional violations

occur. See Carlson v. Green, 446 U.S. 14, 21 (1980)

(“ [i]t is almost axiomatic that the threat of damages

has a deterrent effect” ) .

The United States invites the Court to depart from its

established jurisprudence by posing what is, in light of

that jurisprudence, the wrong question. The United States

10

asks whether “Congress intended to provide private liti

gants with a right to recover damages under Title IX.”

Brief for the United States in Support of the Petition

for Certiorari at 15. But that is not the issue under the

Court’s precedents. The correct question, as noted above,

is whether Congress explicitly stated an intent to deny

victims of intentional discrimination a damages remedy.

See Guardians, 463 U.S. at 595 (opinion of White, J.) :

Davis, 442 U.S. at 246-47. It is in this respect that con

gressional intent is relevant under the rule of Bell v.

Hood. Congress stated no such explicit intent, as we have

shown.7

The United States incorrectly states the question before

the Court because it misconstrues this Court’s cases,

First, in support of its argument that Congress must

have shown an intent to create a damages remedy before

damages may be awarded, it relies solely on cases and

language of this Court concerning whether Congress in

tended to create a cause of action. See Brief for the

United States in Support of the Petition for Certiorari

at 14 & n.22.8 Under the cases discussed above, affirm

ative congressional intent may be the touchstone in

creating a cause of action, but it is relevant only in

7 The United States’ formulation of the issue would require Con

gress to be more specific in affording remedies under implied causes

of action than under expressly created causes of action. See

Wyandotte Transp., 389 U.S. at 200-04; see also Cort, 422 U.S. at

82-83 & n.14. Indeed, the inquiry advanced by the United States

could result in very little relief being available under the Title IX

implied cause of action or other implied causes of action, since it is

“hardly surprising” for there to be little explicit congressional intent

regarding remedies when Congress did not explicitly create a cause

of action. See Brief for the United States in Support of the Petition

for Certiorari at 15.

8 Of course, this Court already has ruled that Congress intended

a private right of action to exist under Title IX. Cannon, 441 U.S.

at 694 (“the history of Title IX rather plainly indicates that Con

gress intended to create” a private right of action).

11

determining whether to deny a particular remedy.

Guardians, 463 U.S. at 595 (opinion of White, J . ) ; Davis,

442 U.S. at 246-47. This approach reflects a sound under

standing of the respective roles of Congress and the

courts. Where Congress has created a right of action, it

is traditionally for the courts to determine what remedy

is most appropriate to redress a particular violation. See

Republic Steel Corp., 362 U.S. at 492 (“Congress has

legislated and made its purpose clear; it has provided

enough federal law . . . from which appropriate remedies

may be fashioned even though they rest on inferences.” ).

The rule of Bell v. Hood gives a court the full range of

remedies from which to choose, unless Congress explicitly

has provided otherwise.

Second, the United States misreads this Court’s opin

ion in Transamerica Mortgage. It does so by, once again,

applying in a remedies context language that the Court

used in determining whether a cause of action existed.

Compare Brief for the United States in Support of the

Petition for Certiorari at 14 with Transamerica Mort

gage, 444 U.S. at 15 (“The question whether a statute

creates a cause of action, either expressly or by implica

tion, is basically a matter of statutory construction.” ).

The Court in Transamerica Mortgage, 'consistently with

the principles explained above, denied a damages remedy

to plaintiffs in that case only after determining that

extensive and persuasive legislative history, and the terms

of the statute itself, showed a congressional intent to

deny legal damages to aggrieved plaintiffs. 444 U.S. at

21-22, 29-30 & n.6; see also Bush v. Lucas, 462 U.S.

367, 374-75, 378 (1983) ; Cort, 422 U.S. at 82-83 & n.14.

Congress expressed no such intent when it enacted Title

IX. In fact, the opposite is true. See, e.g., 110 Cong.

Rec. 5256 (1964) (Title VI; comments of Sen. Case)

(cutoff of funds remedy is “not intended to limit the

rights of individuals, if they have any way of enforcing

their rights apart from the provisions of the bill, by way

12

of suit or any other procedure. The [cutoff of funds

remedy] is not intended to cut down any rights that

exist.” ).0 Transamerica Mortgage, therefore, is perfectly

consistent with the framework advanced above and the

result urged by Petitioner.9 10

Finally, the United States seems to advocate that the

Court disregard its well-established rules of construction

because the availability of compensatory damages under

Title IX would “give rise to a curious anomaly in the

civil rights acts.” Brief for the United States in Support

of the Petition for Certiorari at 17. Such an “anomaly”

would arise, the United States asserts, because a Title

IX plaintiff suing to redress sex discrimination would

have broader remedies than a Title VI plaintiff suing to

redress race discrimination. Id. In addition, the United

States asserts that it would be “especially anomalous”

if the remedies to enforce the implied cause of action

under Title IX were broader than those expressly granted

for employment discrimination in educational institu

tions, under Title VII.11 Id. at 18 n.15.

9 Cannon itself forecloses any argument that Congress intended

only those administrative remedies explicitly provided in Title IX

to be available to aggrieved plaintiffs. Cannon, 441 U.S. at 705.

10 One of the United States’ primary grounds for inferring a

congressional intent to deny a damages remedy for intentional viola

tions of Title IX is that, at the time Congress enacted Title IX,

courts construing Title VI had awarded primarily equitable relief.

Brief for the United States in Support of the Petition for Certiorari

at 16-17. Of course, that would provide no basis for ascertaining

congressional intent at the time Title VI was passed. Thus, to the

extent the Court accepts the United States’ novel argument that

Congress must have intended to create a damages remedy before

the courts may award damages, one of the United States’ primary

methods of “illuminating” congressional intent under Title IX sheds

no light at all on the intended remedies under Title VI.

11 It generally has been held that compensatory damages are not

available under Title VII. See, e.g., Padway v. Patches, 665 F.2d

965, 968 (9th Cir. 1982) ; Pearson v. Western Elec. Co., 542 F.2d

1150, 1151-52 (10th Cir. 1976).

13

The asserted anomalies provide no basis for abandon

ing the normal rules of construction. It is not at all

clear that the remedies under Title IX and Title VI will

differ if compensatory damages are made available for

intentional violations of Title IX. The United States

asserts that such a conflict will arise because persons

alleging employment discrimination on the basis of race

in a federally funded program generally are remitted to

their equitable remedies under Title VII. Brief for the

United States in Support of the Petition for Certiorari at

17. But this Court has never passed on that issue, which

would involve interpretation of provisions in Title VI

that have no counterpart in Title IX.12 It would be put

ting the cart before the horse for the Court to reject the

interpretation of Title IX that is dictated by established

12 Title VI provides th a t:

Nothing contained in this subchapter shall be construed to au

thorize action under this subchapter by any department or

agency with respect to any employment practice of any em

ployer, employment agency, or labor organization except where

a primary objective of the Federal financial assistance is to

provide employment.

42 U.S.C. § 2000d-3 (1988). Title IX contains no analogous provi

sion. The Court previously has noted this difference between Title

VI and Title IX. North Haven, 456 U.S. at 529-30; see also Darrone,

465 U.S. at 631-34 & n.13. Of course, this difference does not suggest

that compensatory damages should be available under Title IX but

not under Title VI. It merely demonstrates that Congress itself

intended Title IX to be somewhat broader in scope than Title VI.

This intent of Congress is not anomalous or even surprising. Con

gress, in conjunction with Title VI, had enacted Title VII which dealt

comprehensively with the national problem of race discrimination

in employment. See North Haven, 456 U.S. at 536 n.26 (“this

Court repeatedly has recognized that Congress has provided a

variety of remedies, at times overlapping, to eradicate employ

ment discrimination”) (citing International Union of Electrical,

Radio & Machine Workers v. Robbins & Myers, Inc., 429 U.S. 229,

236-39 (1976); Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S.

454, 459 (1975); Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 47-

48 (1974)); see also Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co., 424 U.S. 747,

764 (1976); McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 800

(1973).

14

rules of construction, merely to pursue symmetry with

a proposed interpretation of a Title VI provision on which

this Court has never ruled.13 14

As to Title VII, the purported anomaly reflects simply

a different congressional prescription for a different type

of ill. Title VII focuses exclusively on employment, while

Title IX focuses on avoiding the use of federal funds to

support discriminatory practices and giving individuals

“effective protection against those practices.” Cannon,

441 U.S. at 704. As in this case, the damages inflicted

by violations of Title IX may not be primarily economic.

By prescribing equitable remedies in Title VII, Congress

evidently determined that persons who have suffered

economic injuries due to race discrimination in employ

ment, generally in a private context, should not have the

same breadth of remedies as individuals who have suf

fered intentional discrimination by recipients of federal

funds.11

II. THERE ARE NO ELEVENTH AMENDMENT OR

OTHER CONSTITUTIONAL CONCERNS THAT

WARRANT RESTRICTION OF THE REMEDIES

AVAILABLE UNDER TITLE IX.

To justify its denial of a damages remedy, the court

of appeals relied heavily on certain principles of federal

ism, rooted in the Eleventh Amendment and related no

tions of State autonomy, that come into play in inter

13 In any event, an individual who sues for race discrimination in

employment is entitled to recover compensatory damages under 42

U.S.C. § 1981. See Johnson, 421 U.S. at 460.

14 Even if the United States had provided a persuasive rationale

for changing the rule of construction as to remedies, which it has

not, the Court should not apply a new and different rule with respect

to statutes passed when the Bell v. Hood rule of construction applied.

See Welch v. Texas Highways & Put. Transp. Dep’t, 483 U.S. 468,

496 (1987) (Scalia, J., concurring in part) ; Transamerica Mortgage,

444 U.S. at 32 n.8 (White, J., dissenting); Cannoji, 441 U.S. at 698

nn.22 & 23; id. at 718 (Rehnquist, J., concurring).

15

preting federal statutes enacted pursuant to the spending

power. Without expressly saying so, the court below

apparently concluded that those concerns warrant de

parture from the “usual rule” of Bell v. Hood in deter

mining what remedies are available against State or local

governments for violation of a federal spending power

statute. That conclusion, we submit, was erroneous.15

The principles on which the court of appeals relied

were developed by this Court in Pennhurst State School

& Hosp. v. HaXderman, 451 U.S. 1 (1981). The Court

there noted the contractual nature of Spending Clause 16

enactments and the fact that such enactments frequently

impose substantial financial and administrative burdens

on State and local governments. Where Congress seeks

to impose “affirmative obligations” on the States under

its spending power, the Court concluded that it must do

so clearly and unambiguously. See Pennhurst, 451 U.S.

at 16-17 (emphasis in original).17

15 The court of appeals also relied on the decision of the former

Fifth Circuit in Drayden v. Needville Indep. School Dist., 642 F.2d

129 (5th Cir. 1981), which rejected a claim for backpay under Title

VI. This was error. After Drayden was decided, this Court unani

mously ruled that a victim of intentional employment discrimination

at the hands of a recipient of federal financial assistance may recover

backpay as compensation. Darrone, 465 U.S. at 630-31. Thus

Dray den’s rejection of any “right to recover backpay or other

losses,” and its sweeping assertion that the “private right of action

allowed under Title VI encompasses no more than an attempt to have

any discriminatory activity ceased,” 642 F.2d at 133, have no current

vitality.

18 The Spending Clause, U.S. Const, art. I, § 8, cl. 1, states that

Congress “shall have Power . . . to pay the Debts and provide for

the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States.”

17 The Pennhurst Court found support for its contractual analysis

of Spending Clause legislation in Justice Cardozo’s opinion for the

Court in Steward Machine Co. v. Davis, 301 U.S. 548, 585-98 (1937).

In Steward Machine, the Court upheld the constitutional validity of

the federal Social Security tax system over the complaining tax

16

Applying these principles in Guardians, 463 U.S. at

596-97, Justice White (joined by Chief Justice Rehn-

quist) expressed the view that only a prospective injunc

tion should issue against a municipality whose hiring

criteria were found to have excluded a disproportionate

number of minority applicants, allegedly in unintentional

violation of Title VI. Justice White reasoned that, in a

case of unintentional discrimination, the defendant can

not properly be said to have violated the contractual

conditions placed on its receipt of federal funds until

such time as a court has identified the discriminatory

impact of its conduct and announced what further costs

and obligations it must undertake in order to comply

with the law. He concluded that retrospective relief is

inappropriate under those circumstances, because the re

cipient of funds—presented, for the first time, with a

clear statement of the duties that it must assume should

it continue to accept federal monies—is entitled to make

an informed choice: The recipient may reject the con

tractual conditions by withdrawing from the federal as

sistance program entirely, see Rosado v. Wyman, 397

U.S. 397, 420-21 (1970), or it may “voluntarily and

knowingly” accept those conditions, “cognizant of the

consequences of [its] participation” in the program, Penn-

hurst, 451 U.S. at 17. Finally, Justice White noted that

the analysis he derived from Pennhurst and Rosado was

roughly analogous to the Eleventh Amendment’s general

prohibition against retroactive relief in a federal-court

action against a State official. See Guardians, 463 U.S.

at 604 (citing Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651, 665-67

(1974)).

Five members of the Court disagreed with the remedial

limitations proposed by Justice White, arguing that the

payers’ objection that Congress, by conditioning certain grants to

the States on their own enactment of unemployment compensation

laws, had resorted to “coercion of the States in contravention of the

Tenth Amendment or of restrictions implicit in our federal form of

government.” Id. at 585.

17

Eleventh Amendment was inapplicable and that Penn-

hurst—itself an outgrowth of State sovereign immunity-

doctrine—addresses only the specificity with which Con

gress must legislate under the Spending Clause in order

to create rights that are judicially enforceable against

the States, and does not limit the remedies available when

those rights have been violated.18 Justices Stevens, Bren

nan, and Blackmun, as well as Justice Marshall in a sep

arate opinion, rejected any inflexible rule limiting the

remedies available under Title VI. See Guardians, 463

U.S. at 628-33, 636-38. Justice O’Connor, for the same

reasons, rejected the proposed distinction between pro

spective and retrospective equitable relief, but found it

unnecessary to address the availability of monetary dam

ages, see id. at 612 & n.l, because she concluded that no

violation of law had been established. And Justices

White and Rehnquist cautioned that a Pennhurst con

tractual analysis might well lead to the opposite result

in a Title VI case involving intentional discrimination,

where there is “no question as to what the recipient’s

obligation under the program was and no question that

the recipient was aware of that obligation.” Id. at 597.

In such situations, “it may be that the victim of the

intentional discrimination should be entitled to a com

pensatory award . . . .” Id.

Pennhurst does not, as the court of appeals believed,

prohibit the relief sought here.19 Respondents’ alleged

18 The majority’s disagreement with Justice White over the mean

ing and limits of Pennhurst mirrors the debate that divided the

Seventh Circuit panel in Lieberman v. University of Chicago, 660

F.2d 1185 (7th Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 456 U.S. 937 (1982). See id.

at 1189-92 (Swygert, S.J., dissenting).

19 The court of appeals assumed that ‘'Title IX, like Title VI, is

Spending Clause legislation,” Cert. Pet. App. 11, and therefore found

“important guidance” in Justice White’s application of Spending

Clause principles in Guardians. But in Guardians the parties had

not briefed the question of Title Vi’s constitutional origins, because

18

violation lies not in any failure to predict what hidden

obligations and duties a court might declare to be im

plicit in Title IX, cf. Guardians, 463 U.S. at 597, but in

a willful disregard of a clear and unambiguous statutory

command. Where a recipient of federal funds has inten

tionally violated the unequivocal congressional mandate

they, like the Congresses that enacted Title VI and Title IX, had no

reason to anticipate that the answer to that question would affect

the availability of particular remedies. In fact, there is compelling

evidence that the 88th Congress enacted Title VI pursuant to Section

5 of the Fourteenth Amendment as well as its Article I power to

spend for the general welfare. See 110 Cong. Rec. 1529 (1964)

(Rep. McCulloch) (“ [T]he Federal Government, through Congress,

certainly has the authority, pursuant to the 14th amendment, to

withhold Federal financial assistance where such assistance is ex

tended in a discriminatory manner.”) ; H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th

Cong., 1st Sess. pt. 2, at 1 (1963) (“ [N]ot since Reconstruction has

Congress enacted legislation fully implementing the [Fourteenth

Amendment]. A key purpose of the bill, then, is to secure to all

Americans the equal protection of the laws of the United States

and the several states.”) ; 110 Cong. Rec. 1527 (1964) (Rep. Celler)

(suggesting that, although Title VI is undoubtedly valid as an exer

cise of the spending power, the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments

may of their own force prohibit the expenditure of public funds to

support discriminatory programs and activities) ; id. at 13,333 (Sen.

Ribicoff) (stating that Title VI enacts procedures for enforcing the

Fourteenth Amendment). See also Regents of the Univ. of Cali

fornia v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 285-87 (1978) (opinion of Powell, J.).

There are many reasons, including the evolutionary nature of

constitutional doctrines, that might lead Congress to invoke more

than one of its constitutional powers in enacting civil rights or other

remedial legislation. See Note, The Eleventh Amendment and State

Damage Liability Under the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, 71 Va. L.

Rev. 655, 679 & nn.174-77 (1985) (“Because at the time the [1964]

Civil Rights Act was drafted, Congress could enforce the fourteenth

amendment only against state governments, Congress applied Title

VI to private recipients of federal aid through its broad article I

powers.” ) (citing, inter alia, The Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3

(1883)). For the courts to limit the reach of a statute based on

their j udgment as to the predominant source of constitutional power

invoked would effectively deny Congress its ability to base legislation

on more than one.

19

accompanying those funds, the recipient should be held

to the terms of its bargain and should “make whole” the

victim of its misconduct.20 The time for the recipient

to shed an unwanted obligation not to discriminate, and

to avoid liability for an intentional breach of that obliga

tion, has long since past.

Pennhurst also does not control the result here because,

three years after the Court decided Guardians, Congress

explicitly rejected the importation of Eleventh Amend

ment principles into Title IX litigation. In the Civil

Rights Remedies Equalization Act of 1986 (“Remedies

20 The United States, as amicus curiae, posits a distinction between

permissible and impermissible make whole relief that turns on

whether the relief “would threaten ‘a potentially massive financial

liability’ ” or whether, instead, it “ ‘merely requires the [defendant]

to belatedly pay expenses that it should have paid all along.’ ” Brief

for the United States in Support of the Petition for Certiorari at

19 & n.17 (citations omitted). That distinction would, for no ap

parent reason, elevate the State sovereignty concerns noted in

Pennhurst (e.g., that a court should not lightly require the States

to assume “open-ended and potentially burdensome obligations,”

451 U.S. at 29) into a free-standing rule of statutory construction

favoring restitutionary remedies over legal damages. There is no

valid basis for such a rule. This Court’s Eleventh Amendment cases

draw no distinction between compensatory damages and restitution

of benefits wrongly withheld. See Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S.

445, 452 (1976) (an award of retroactive retirement benefits is a

“damages award”). Nor does any such distinction follow, as the

United States suggests, from Title IX’s references to voluntary

compliance with the law.

As the United States correctly notes, Title IX by its terms pro

hibits three distinct forms of misconduct by recipients of federal

aid. See Brief for the United States in Support of the Petition for

Certiorari at 15-16. A wrongful “exclusion from participation” may

sometimes be cured by a prospective injunction, and an unlawful

“denial of benefits” may sometimes be cured by relief in the nature

of restitution. But the rule proposed by the United States would

often provide no judicial remedy at all for having been “subjected

to discrimination” in violation of Title IX. Such a gap in the stat

ute’s coverage would be wholly irrational.

20

Act”),21 22 Congress not only eliminated any grounds for

withholding retroactive relief under Title IX, but also

rejected any distinction between legal and equitable relief.

Congress enacted the Remedies Act as part of the

Rehabilitation Act Amendments of 1986, in response to

this Court’s decision in Atascadero State Hosp. v. Scanlon,

473 U.S. 234 (1985).22 The Act contains two substantive

provisions. The first, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d-7 (a) (1), with

draws the Eleventh Amendment immunity of the States

under Title IX and related statutes. The second, 42

U.S.C. § 2000d-7(a) (2), goes further. Eschewing any

distinction between legal and equitable relief under Title

IX, the Remedies Act clarifies that, in a Title IX suit

against a State, a federal court may provide “remedies

both at law and in equity” :

In a suit against a State for a violation of a statute

referred to in paragraph (1), remedies (including

remedies both at law and in equity) are available'

for such a violation to the same extent as such reme

dies are available for such a violation in the suit

against any public or private entity other than a

State.23

Congress obviously understood that remedies “at law”

are available under Title IX, and acted to ensure that

21 Pub. L. No. 99-506, § 1003, 100 Stat. 1807, 1845 (1986) (codi

fied at 42 U.S.C. § 2000d-7 (1988)).

22 In Atascadero, the plaintiff sought “retroactive monetary relief”

for an allegedly discriminatory refusal to hire—apparently the same

equitable remedy approved in Darrone, 465 U.S. at 631—against two

agencies of the State of California. This Court held the claim barred

by the Eleventh Amendment.

23 42 U.S.C. § 2000d-7(a)(2) (1988). The statutes “referred to

in paragraph (1)” of this subsection are Section 504 of the Rehabili

tation Act, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, the Age

Discrimination Act of 1975 (42 U.S.C. §6101 et seq.), Title VI of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and “the provisions of any other

Federal statute prohibiting discrimination by recipients of Federal

financial assistance.” None of the enumerated statutes textually

provides a damages remedy.

21

those remedies will be available against public as well

as private defendants. If, as Respondents here contend,

remedies “at law” are never available under Title IX,

then the language chosen by Congress is effectively deleted

from the statute. Such a result is strongly disfavored.

See Rosado, 397 U.S. at 415 (“courts should construe

all legislative enactments to give them some meaning”) ;

United States v. Menasch, 348 U.S. 528, 538-39 (1955)

(courts should “give effect, if possible, to every clause

and word of a statute”) ; 2A N.J. Singer, Sutherland

Statutory Construction § 46.06, at 104 (4th ed. 1984).

The legislative history of the Remedies Act further

confirms that Congress understood that the federal courts

were, and intended that they remain, free to provide a

damages remedy under Title IX. Congress had assumed,

before Atascadero, that money damages were available

against the States, and a fortiori that money damages

were available against other public entities and private

parties. Thus, when Congress acted to “equalize” the

remedies available against the States, it did so by “ex

plicitly providing] that in a suit against a State for

a violation of any of these statutes, remedies, including

monetary damages, are available to the same extent as

they would be available for such a violation in a suit

against any public or private entity other than a State.”

S. Rep. No. 388, 99th Cong., 2d Sess. 28 (1986) (empha

sis added) ,24

24 If, as the court of appeals believed, the Remedies Act “only elimi

nates the sovereign immunity of States under the eleventh amend

ment,” Cert. Pet. App. 10 (emphasis added), then the entire text

of paragraph (a)(2) of the Act is simply read out of the statute.

Compare 42 U.S.C. § 2000d-7(a) (1) (“A State shall not be immune

under the Eleventh Amendment . . . .” ) with id. § 2000d-7(a) (2)

(“remedies (including remedies both at law and in equity) are

available . . . .”). The Senate Report confirms that paragraph (a) (2)

was intended to have independent significance. See S. Rep. No. 99-

388, at 28 (“ [T]he Rehabilitation Act Amendments of 1986 provide

that states shall not be immune under the Eleventh Amendment from

suit in Federal court. . . . Section 1003 also explicitly provides that

22

Senator Cranston, the author of the Remedies Act,

voiced its underlying premise—the need for a federal

damages remedy—quite plainly in explaining the urgency

of its enactment.25 He explained that the result in Atas

cadero was unacceptable because it left victims of dis

crimination by the States with only two choices: a “fed

eral suit for an injunction against individual State offi

cials” or “a suit in State court for damages.” 132 Cong.

Rec. 28,623 (1986) (emphasis added). He then cogently

explained how the federal courts’ inability or refusal to

in a suit against a State for a violation of any of these statutes,

remedies, including monetary damages, are available [against the

State] . . . .” ).

Moreover, if Respondents’ view were to prevail, then the 99th

Congress, despite its reference to “remedies both at law and in

equity,” accomplished no more than to make retroactive equitable

relief available in private actions in federal courts against the

States; prospective relief was already available through the simple

expedient of suing the responsible State official rather than the

State itself, under the doctrine of Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123

(1908). See Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651, 664 (1974) (State

official prospectively enjoined to comply with federal regulations).

Congress plainly believed that it was accomplishing more than this.

25 The Remedies Act was incorporated into Title X of the Rehabili

tation Act Amendments of 1986 after being offered as an amendment

to the Senate bill by Senator Cranston. See S. Rep, No. 99-388, at

27. The original House bill (H.R. 4021) contained no comparable

provision, but Senator Cranston’s language was adopted by the

Conference Committee without any material change, and the House

passed the resulting version of H.R. 4021 containing Senator

Cranston’s provision by a vote of 408-0. See 132 Cong. Rec. 28,094-

95 (1986).

Because the Conference Committee Report does not refer to Sena

tor Cranston’s amendment except to clarify its effective date, see

H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 955, 99th Cong., 2d Sess. 78-79 (1986), and

because the bill originally reported by the House Education and

Labor Committee contained no equivalent provision, the only con

temporaneous explanations of Congress’s choice of the words “reme

dies both at law and in equity” are those in the Senate Report and

those offered on the Senate floor by Senator Cranston, the amend

ment’s author and primary sponsor.

23

award damages would thwart the remedial objectives of

the civil rights laws:

As to the limit on Federal remedies, litigation in

volving a claim of discrimination often takes years

to resolve. Thus, where the [victim] is seeking em

ployment or is trying to pursue an education or to

participate in a project having only a 2- or 3-year

life, an injunction may come too late to be [of]

value in remedying the harm done through the un

lawful discrimination. In a very real sense, the

availability of only injunctive relief postpones the

effective date of the antidiscrimination law, with

respect to a State agency, to the date on which the

court issues an injunction because there is no remedy

available for violations occurring before that date.

Id. That is the unacceptable result that Congress sought

to foreclose when it enacted the Remedies Act. Yet it

is exactly the result that would follow from the court of

appeals’ holding in this case.

The United States offers a contrary reading of Senator

Cranston’s explanatory statement. Truncating his re

marks beyond recognition, the Government asserts that

Senator Cranston “carefully reserved” the question

whether damages are available under Title IX. Brief for

the United States in Support of the Petition for Cer

tiorari at 20 n.18. That assertion is baffling. If the

Senator did not believe that legal damages were recover

able against private parties, why then did he assume

them to be recoverable against the States in their own

courts? And if Congress did not intend that full retro

active relief be made available to victims of unlawful

discrimination, why then did it reject the States’ con

stitutional immunity as impermissibly “postpon [ing]

the effective date of the antidiscrimination law”?

The Government’s casual dismissal of the Remedies

Act not only turns Senator Cranston’s statement on its

head, but also undermines the Government’s own pro

fessed goal of effectuating the intent of Congress. If

24

the Remedies Act does nothing more, it forcefully demon

strates Congress’s intent that the full range of the fed

eral courts’ remedial powers be available to compensate

victims of unlawful discrimination. In the Remedies Act,

Congress acted to overcome a constitutional barrier that

prevented the courts from awarding damages under Title

IX. If another barrier is to be erected, it cannot be done

in the name of congressional Intent.

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, the judgment of the court below

should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

William T. Lake

Counsel of Record

David R. H ill

Stuart Cane

Wilmer, Cutler & P ickering *

2445 M Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 200B7

(202) 663-6000

William H. Brown III

Co-Chairman

Herbert M. Wachtell

Co-Chairman

Norman Redlich

Trustee

Barbara R. Arnwine

Thomas J. Henderson

Paul H oltzman

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil R ights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

August 14,1991 (202) 371-1212

* Alexandra B. Klass, a student at the University of Wisconsin

Law School, and Lisa M. Winston, a student at Harvard Law School,

assisted in the preparation of this brief.