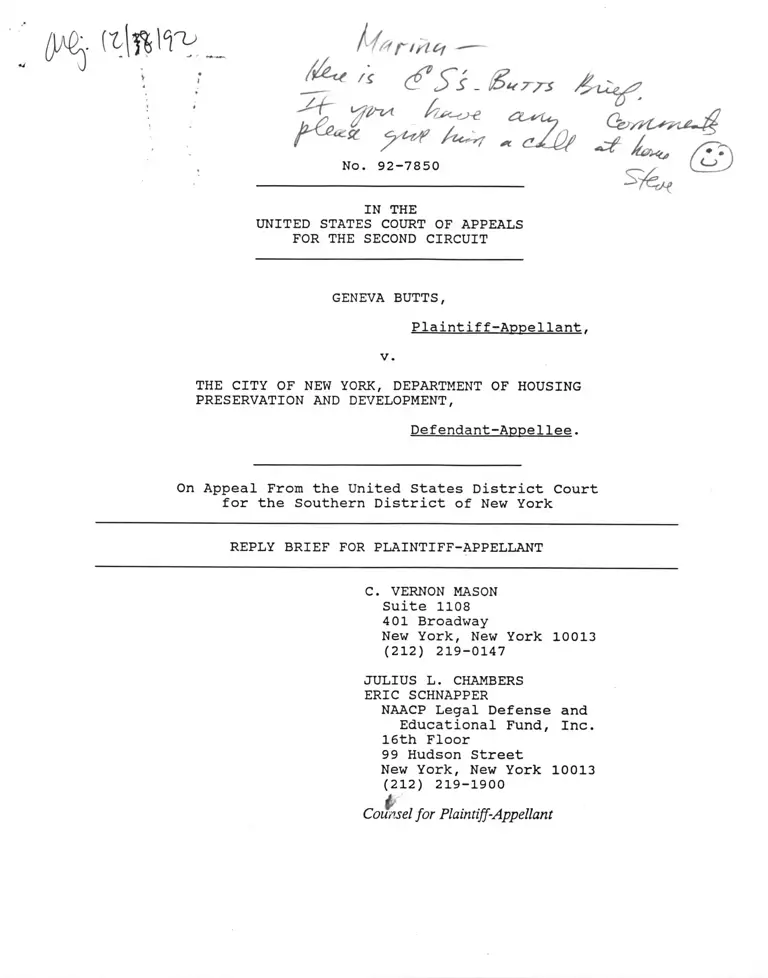

Butts v The City of New York Department of Housing Preservation and Development Reply Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant

Public Court Documents

November 4, 1992

66 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Butts v The City of New York Department of Housing Preservation and Development Reply Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant, 1992. 2cec113d-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/430192a6-0e03-454e-b529-7d2e6c3599f9/butts-v-the-city-of-new-york-department-of-housing-preservation-and-development-reply-brief-for-plaintiff-appellant. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

"iU

( f S t . &

i t «-***,

r ^ « ? * « * ~ t ~ ̂

Marinct -—

« 7 7 S

No. 92-7850

Oej/yC^i^S^

^ h ^ ij, /♦~T\

% <

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

GENEVA BUTTS,

Plaintiff-Appellant.

v.

THE CITY OF NEW YORK, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING

PRESERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT,

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal From the United States District Court

for the Southern District of New York

REPLY BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

C. VERNON MASON

Suite 1108

401 Broadway

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-0147

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

ERIC SCHNAPPER

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

16th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

i

Counsel for Plaintiff-Appellant

No. 92-7850

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

GENEVA BUTTS,

Plaintiff-Appellant.

v.

THE CITY OF NEW YORK, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING

PRESERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT,

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal From the United States District Court

for the Southern District of New York

REPLY BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN DISMISSING PLAINTIFF'S TITLE VII

CLAIMS

Defendant appears to have abandoned the argument regarding

Title VII on which it prevailed below. The complaint in this

action alleged that on three occasions after the Title VII cut-off

date, January, 1989, plaintiff had been denied promotions because

of her race. (Brief for Appellant, p. 6). In the court below the

defendant argued, and the district court ruled, that these

promotion denials were not actionable because they were not

"related to" the allegations in plaintiff's 1989 EEOC charge.

(J.App. 27a, 46a, 127a). In this court, however, defendant does

not assert that the promotion denials that occurred within the

limitations period were not related to the repeated allegations in

the Title VII charge of discriminatory denials of promotions.

(Appellee's Brief, pp. 12-17).1

Defendant also argued below that each time a new act of

discrimination occurs subsequent to the filing of a Title VII

charge, the victim must file a new Title VII charge.2 In this

court, however, the defendant expressly disavows that position.3

On appeal, defendant now advances a new contention, that the

allegations of discrimination in the Title VII charge, even if

reasonably related to alleged discriminatory conduct within the * VII

This change in defendant's position is apparent on the

face of defendant's brief. Defendant correctly describes the

district decision as having dismissed plaintiff's 1989, 1990 and

1991 claims on the grounds that they were not "'related to the

allegations' in the EEOC charge (127a)." (Appellee's Brief, p. 10,

quoting district court opinion). But defendant describes the issue

presented on appeal as follows:

Did the District Court properly find plaintiff's Title

VII claims time-barred for failure to make a timely

complaint to the . . . EEOC where plaintiff's EEOC charge

did not mention any specific act of discrimination within

the 300-day limitations period?

(Id. p. 1) . The district court opinion, as defendant's own

description makes clear, was not based on and makes no mention of

any "specific act" requirement.

"The amended complaint has added two new allegations

which unquestionably fall outside of this Court's subject matter

jurisdiction.... Both allegations describe discrete, completed

acts which occurred months or years after plaintiff's EEOC filing.

As a prerequisite to raising the allegations in the District Court

plaintiff was required to have raised them before the EEOC within

300 days of their occurrence". (J.App. 47a) (Emphasis added).

"[I]t would be improper to require a Title VII plaintiff

to make repeated trips to the EEOC to bring suit on subsequent acts

of discrimination...." (Appellee's Brief, p. 17). The EEOC

internal procedures expressly require consideration of post-charge

violations. C CH EE O C Compliance Manual §22.5, 5805, p. 719.

2

The Titlelimitations period, were not sufficiently "specific."

VII charge alleged that plaintiff was subjected to a variety of

particular practices to prevent her from obtaining promotions,

including being "discouraged from applying," being "denied ...

consideration," unwarranted criticism of her "work performance ...

to justify my being passed over," and denials or rejections of

"several requests for advancement." (J.App. 10a-13a).

Defendant contends that these allegations of discriminatory

treatment within the limitations period were insufficient to

support any Title VII claim.

[T]he charge ... filed with the EEOC did not allege any

specific act of discrimination within the .. . limitations

period. .. . The only specific acts of discrimination

mentioned in plaintiff's EEOC charge occurred long before

the limitations period....

(Appellee's Brief, p. 12). Defendant's contention appears to be

that a Title VII charge is insufficient as a matter of law, even

though it alleges a pattern of discriminatory promotion denials and

specifies the particular types of practices utilized to deny

promotions, unless the charge also lists the particular promotions

which were unlawfully denied.

The harsh specificity requirement advocated by defendant is

clearly inconsistent with the well established meaning of Title

VII.

Nothing in the Act commands or even condones the

application of archaic pleading concepts. On the

contrary, the Act was designed to protect the many who

are unlettered and unschooled in the nuances of literary

draftsmanship. It would falsify the Acts hopes and

ambitions to require verbal precision and finesse from

3

those to be protected, for we know that these endowments

are often not theirs to employ.

Sanchez v. Standard Brands, 431 F.2d 455, 465 (5th Cir. 1970).

A Title VII charge is deemed to encompass any discriminatory

acts that would be "within the scope of the EEOC investigation

reasonably expected to grow out of" the charge. Miller v. International

Telephone and Telegraph Corp., 755 F.2d 20, 23-24 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 474

U.S. 851 (1985). Under Miller the question here is whether the

denials of promotions in 1989, 1990 and 1991 could reasonably be

expected to be within the scope of an investigation of a charge

that alleged:4

I have been denied promotional opportunities and

consideration based on my race....

* * *

I was discourage from applying for a higher position of

authority.

* * *

I was denied . . . promotional advancement and upward

career mobility, I have made several requests for

advancement that were thwarted....

I feel allegations criticizing my work performance were

made to justify my being passed over for promotions.

(J.App. 10a-13a) . Upon receipt of such charges, EEOC could

reasonably be expected to investigate an instance in which the

charging party had been denied a promotion from the beginning of

the limitations period until the point when the investigation was

The 1989 charge was pending before the EEOC until May

1991. (J.App. 105a-106a).

4

completed. Such an investigation which would encompass the 1989,

1990 and 1991 promotions at issue in this case. Defendant's

proposed specificity rule would made sense only if it were EEOC's

practice to conduct no investigation whatever of charges such as

those quoted above, since any investigation of these charges could

be expected to include promotion denials in 1989-91. Defendant

does not, however, seriously contend that EEOC would, or legally

could, refuse completely to investigate such charges.

Defendant acknowledges that the EEOC charge in this case also

alleged discrimination in the terms and conditions of plaintiff's

employment, but asserts these allegations were "based on events in

1987, well before the limitations period." (Appellee's Brief, p.

15 n.6). That simply is not correct. Six paragraphs of the Title

VII charge deal with discriminatory terms and conditions of

employment.5 Of these only one, paragraph 7, contains any

reference to 1987.

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN HOLDING PLAINTIFF'S PROMOTION

CLAIMS ARE BARRED BY PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT UNION, 491

U.S. 163 (1989)

Defendant clearly abandons the argument on which it prevailed

below. In the district court defendant advanced two arguments

regarding plaintiff's section 1981 claims. First, in response to

plaintiff's pro se complaint, defendant contended that the complaint

Paragraphs 4 ("denied equal terms and conditions"), 7

("limited contact" with supervisor), 8 ("not included in

meetings"), 9 (exclusion from meetings, loss of staff), 11

(exclusion from discussions), 12 (tactics "designed to force my

resignation"). (J.App. 10a-13a) .

5

referred to only one disputed promotion, and did "not mention the

outcome" of plaintiff's application. (J.App. 30a-31a). The

Amended Complaint resolved any such defect, and defendant no longer

advances this argument. Second, in response to the section 1981

claims in Amended Complaint, defendant made only one argument, that

"allegations of discrimination occurring prior to August 5, 1988,

are barred by the statute of limitations." (J.App. 50a).

Defendant advanced no argument regarding post-1988 section 1981

claims. The district court's opinion proceeds on the assumption

that Patterson bars all section 1981 promotion claims. (J.App. 131a) .

On appeal defendant acknowledges that certain section 1981 types of

promotion claims do survive Patterson, and that some of the disputed

promotions were made within the limitation period.

In this court defendant advances an altogether new argument —

that the Amended Complaint does not contain sufficiently specific

allegations regarding the responsibilities and circumstances of the

various promotions at issue. In the district court defendant

advanced no objection to the specificity of the Amended Complaint.

On appeal, however, defendant for the first time argues that the

Amended Complaint was defective because it failed to "plead facts

that would allow a comparison between the plaintiff's present job

and the responsibilities of the promotional position," (Appellee's

Brief, p. 19), and that therefore "it was proper to dismiss this

cause of action in light of her failure to do so." {Id . , pp. 19-20)

This argument is for several reasons unavailing.

6

First, of course, the district court did not dismiss the

complaint "in light of" any lack of specificity in the complaint.

The district court decision was based on the assumption that any

allegation of discrimination in promotion, however specific, would

not state a cause of action under Patterson.

Second, an objection to the specificity of a complaint must be

made in the district court, and cannot be raised only after a case

is on appeal. In the instant case, however, the defendant offered

no objection in the district court to the specificity of the

section 1981 claims, and cannot do so for the first time on appeal.

An objection to the specificity of a complaint is ordinarily made

in the form of a Motion for More Definite Statement under Rule

12(e), F.R.C.P. A party filing such a motion is required to "point

out the defects complained of and the details desired," thus

affording the opposing party an opportunity to file an amended

pleading with whatever additional specificity the court may

require. In some instances, the absence of an assertedly essential

allegation or denial in a complaint or answer may be raised by a

Motion for Judgment On the Pleadings, under Rule 12(c). But here,

too, the motion must in the first instance be made in the district

court, so that the opposing party is afforded a reasonable

opportunity to remedy any defect in the pleading. The requirement

of Rule 15(a), that leave to make needed amendments to pleadings

"be freely given when justice so requires," could easily be

defeated if a party were permitted to wait until a case was on

appeal before objecting to the sufficiency of a pleading.

7

Third, there is nothing in the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure requiring a plaintiff in a case such as this to "plead

facts that would allow comparison between the plaintiff's present

job and the responsibilities of the promotional position."

(Appellee's Brief, p. 19) . A motion for judgment on the pleadings,

whether by a plaintiff or by a defendant, will rarely if ever be

useful in applying the Patterson "new and distinct relation standard."

That standard, as our opening brief makes clear, depends on the

particular circumstances of each case. There may be some cases in

which the undisputed facts will be sufficient to dispose of this

issue, but the procedural device for identifying such cases is a

motion for summary judgment under Rule 56. Rule 56, particularly

as implemented by the local rules in the Southern District of New

York, provides a straightforward and practicable method of

delineating undisputed facts that may make trial of an issue

unnecessary. Attempts to achieve that result by attacks on the

specificity of pleadings would be inconsistent with the modern

practice of notice pleading, and would result in a revival of bills

of particulars, which were rejected by the federal courts as

unworkable almost half a century ago. (See 1946 comment on Rule

12(e)).

III. THE 1991 CIVIL RIGHTS ACT SHOULD BE APPLIED TO THIS CASE

For the reasons set out above, plaintiff's Title VII claims

and section 1981 claims must be remanded for trial. The complaint

in this case states a cause of action regardless of whether the

1991 Civil Rights Act applies to the claims asserted. The

8

applicability of the 1991 Act to this case should nonetheless be

addressed on appeal because it's applicability will on remand

affect the standard of proof, the type of trial, and the available

remedy:

(a) If either section 101 or 102 of the Act applies,

plaintiff will not be required to establish that the

promotions at issue involved a "new and distinct

relation" in order to obtain damages for the denial of

those promotions;6

(b) If either section 101 or 102 applies, plaintiff will be

entitled to seek damages if she establishes

discrimination in the terms and conditions of her

employment.

(c) Whether sections 101 and 102 apply will affect which

issues will be tried to the jury.7

Under the particular circumstances of this case, application of

section 101 would have the same effect as application of section

Damages occasioned by discrimination in promotion are

already available under section 1981. If section 101 were held

inapplicable here, the applicability of section 102 would then be

of importance, since Title VII does not require proof of a new and

distinct relation.

The Amended Complaint requested a jury trial. (J.App.

102a). Even absent application of the 1991 Act, plaintiff's

section 1981 promotion claim will have to be tried to the jury. A

jury determination that plaintiff was (or was not) denied a

promotion on account of race would be binding on the judge in

deciding the Title VII claim. However, whether there is to be a

jury trial on plaintiff's terms and conditions claims will turn on

the applicability of section 101 and 102.

9

102; thus a determination that either section applies would be

sufficient to dispose of this aspect of the appeal.

In our opening briefs we advanced several arguments in support

of our contention that the 1991 Act should be applied to this case.

Although each of these contentions, if accepted by the court, would

result in a decision in favor of appellant, the impact of our

arguments on other types of cases varies considerably. We

recognize that the court may prefer to resolve the instant appeal

on a narrower ground, choosing to avoid for the time being

addressing issues affecting other cases. Accordingly, in replying

to Appellee's Brief we set forth first the more narrow of our

contentions, noting in each instance the types of cases that would

be affected by decision on each contention.

(1) Non-Retro activity o f Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 491 U.S. 104

(1989) . We urged in our opening brief that the decision in Patterson

itself should not be applied retroactively in light of the passage

of the 1991 Act. (Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant, pp. 44-47). This

is the narrowest of the arguments we advance. It would affect only

section 1981 claims that arose prior to June 15, 1989, the date of

the decision in Patterson, and would not require any decision as to

the retroactivity of the 1991 Act itself. Defendant's brief on

appeal does not address this issue.

(2) The Restorative Provisions of the 1991 A ct - As the defendant appears

to acknowledge, the decision of this court in Leake v. Long Island Jewish

Medical Center, 869 F.2d 130, 131 (2d Cir. 1982), holds that

10

legislation which Congress regarded as restorative should be

applied to all pending cases. (Appellee's Brief, p. 25; Brief for

Plaintiff-Appellant, pp. 42-44). Application of Leake to hold

section 101 applicable to the instant case would not be dispositive

of the retroactivity of the rest of the 1991 Act. Section 102, for

example, which for the first time authorizes compensatory and

punitive damages in Title VII actions, clearly is not

restorative. The issue critical to the applicability of Leake is

whether Congress understood that the provision at issue was merely

restoring the law to where it had stood prior to an intervening

decision being overturned by Congress.

Defendant argues that Congress did not regard section 101 as

restoring the pr e-Patterson interpretation of section 1981. In

support of this view, defendant relies primarily on the fact that

early versions of the legislation contained a statement, absent

from the version finally enacted, that the purposes of the law

included "restoring the civil rights protections that were

dramatically limited by" the Supreme Court's "recent decisions."

(137 Cong. Rec. at 3923 (daily ed. June 5, 1991)); Appellee's

Brief, p. 24). The legislative history of the 1991 Act, however,

makes clear that this change in language did not reflect a

determination by Congress that section 101 was not restorative.

The new statement of legislative purpose by defendant was

purposed by Senator Danforth and a group of moderate Republicans on

June 4, 1991. (137 Cong. Rec. S 7021 (daily ed. June 4, 1991)).

When the final legislation was agreed upon in October 1991,

11

incorporating Danforth's statement of purpose and draft of section

101, Danforth and the other framers of this proposal reiterated

that it was restorative. Senator Danforth placed in the

Congressional Record a Sponsor's Interpretative Memorandum, on

behalf of himself and the original cosponsors, explaining that

section 101:

fills the gap in the broad statutory protection against

intentional racial and ethnic discrimination covered by

section 1981 ... that was created by the Supreme Court

decision in P a tte r s o n ... . Section [101] reinstates the

prohibition of discrimination during the performance of

the contract and restores protection from racial and ethnic

discrimination to the millions of individuals employed by

firms with fewer than 15 employees.

(137 Cong. Rec. S 15483 (daily ed. Oct. 30, 1991)) (emphasis

added). Senator Jeffords, one of the original cosponsors of the

Danforth language, also explained that the legislation "will restore

the rights taken away in Patterson." (137 Cong. Rec. S 15383 (daily

ed. Oct. 29, 1991)) (Emphasis added). Other members of Congress

joined Danforth and the original cosponsors in the final version of

the 1991 Act describing section 101 as restoring the law to where

it had been prior to Patterson.fi

See, e.g. 137 Cong. Rec. S 15235 (daily ed. Oct. 25,

1991) (Sen. Kennedy) (section 101 "will reverse ... Patterson . . . and

restore the right of Black Americans to be free from racial

discrimination in the performance — as well as the making — of

job contracts"); 137 Cong. Rec. S 15489 (daily ed. Oct. 25, 1991)

(Sen. Leahy) ("The Patterson decision drastically limited section

1981's application.... The Civil Rights Act of 1991 returns the

originally intended broad scope of this statute"); 137 Cong. Rec.

H 9526 (daily ed. Nov. 7, 1991). (Rep. Edwards) (section 101

"reinstates" and "restores" law prior to Patterson) .

12

Although other provisions of the proposed civil rights

legislation were highly controversial, there was never any dispute

about the language or desirability of section 101. Equally

significantly, there was never any disagreement that legislation

overturning Patterson would in fact restore what until 1989 had been

well established law. For example, Representative Goodling, one of

the leading opponents of the original 1991 House bill, H.R.l,

described the Administration's own alternative bill as restorative,

even though the Administration bill, like the 1991 Act, contained

no specific statutory language regarding restoration:

[I]t reverses ... the Patterson case.... [T]he

substitute restores the expansive reading of section 1981

that racial discrimination is prohibited in all aspects

of the making and enforcement of contracts.

(137 Cong. Rec. H 3900 (daily ed. June 4, 1991) (emphasis added)).

In the instant case defendant, in interpreting section 101,

attaches decisive significance to the absence of the general

introductory language that was used in H.R. 1. But when

Representative Goodling compared H.R. 1 with the Administration

bill, which also lacked such language, Goodling described H.R. 1 as

"restores expansive reading of Section 1981," and described the

Administration proposal as "same provision," insisting that in this

regard there were "no issues" in dispute between the two proposals.

(137 Cong. Rec. H 3935 (daily ed. June 5, 1991)).

When Senator Kassebaum offered the Administration substitute

in the Senate, she too insisted it was restorative. The relevant

section, Kassebaum insisted, "codifies the broad construction given

13

to 42 U.S.C. 1981 by most lower courts." (136 Cong. Rec. S 9845

(daily ed. July 17, 1990)). In response to assertions that the

Administration bill fell short of fully restoring the pre-Patterson

law, Kassenbaum insisted to the contrary her proposal would indeed

codify "the law as it was prior to Patterson." (Id. at S 9851).

After the final language of the 1991 Act had been agreed upon,

Senator Seymour, a stalwart supporter of the Administration's

position, insisted that the Act "restores section 1981" (137 Cong.

Rec. S 15285 (daily ed. Oct. 28, 1991). No member of the House or

Senate ever disagreed with the repeated assertions that section

101, and its identically worded predecessors would restore the law

to where it stood prior to Patterson. Defendant does not suggest

otherwise. The mere fact that the statutory language of the Act

does not contain a reference to restoration is irrelevant; in both

Leake 695 F. Supp. at 1417, and Mrs. W. v. Tirozzi, 832 F.2d 748, 754-55

(2d Cir. 1987) , the court relied on legislative history to conclude

that Congress regarded the statute at issue as restorative.

There is also no dispute that section 101 in fact returned the

meaning of section 19 81 to that which prevailed prior to Patterson,

and no denying that Congress was well aware that the substance of

section 101 was the same as pr e-Patterson caselaw. As the Ninth

Circuit noted in Davis v. City and County o f San Francisco, 1992 WL 251513

(9th Cir. 1992) ,

[E]vidence of Congress' aims is provided by the

introductory passages of the Act, in which Congress made

no secret of its intent to reverse a number of Supreme

14

Court decisions that it thought construed too narrowly

various employment discrimination statutes.... Given

Congress' sense that the Supreme Court had construed the

Nation's civil rights laws so as to afford insufficient

redress to those who have suffered job discrimination, it

appears likely that Congress intended the courts to apply

its new legislation, rather than the Court decisions....

1991 WL 215513 at *14-*15.

This undisputed understanding that section 101 would restore

prior law was entirely consistent with the prefatory language in

the final bill stating that the bill would provide "additional

remedies" and "additional protections." Given the state of the law

in November, 1991, with Patterson then on the books, section 101 did

provide a protection and remedy in addition to the Supreme Court's

narrow interpretation of section 1981. But the assertion that

section 101 provided remedies and protections "additional" to those

available after Patterson was entirely consistent with Congress'

repeatedly expressed view that what was being added was coverage

necessary to return the law to where it had stood prior to Patterson.

(3) The Remedial Provisions of the 1991 Act - We urged in our opening

brief that under well established precedent, both pre-dating and

following Bradley v. Richmond School Board, 416 U.S. 696 (1974), changes

in the law regarding remedies are presumed applicable to pending

cases, while changes regarding substantive law are presumed not to

be applicable. (Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant, pp. 35-44).

Application of that principle to section 101 and 102 would not

compel the conclusion that the entire 1991 Act is applicable to

15

pending cases, since some provisions of the Act render unlawful

previously lawful conduct, and are therefore substantive.

Defendant urges that a new law should be regarded as

"substantive", and thus presumptively inapplicable to pending

cases, if the law augments the remedy available to plaintiffs, and

thus increases the defendant's "obligations." (Appellee's Brief,

pp. 33-34). This use of the word "obligation" masks a proposal to

effectively overturn the century old distinction between

substantive and remedial laws. In the past a change in the law was

regarded as substantive only if it rendered unlawful previously

lawful conduct; such laws were at times described as creating a

"new obligation," the "obligation" referred to being a standard of

extra-judicial conduct. The adoption in 1964 of Title VII created

such a new obligation in that, for example, Title VII for the first

time established and obligation not to discriminate in employment

on the basis of sex. Defendant does not, of course, contend that

sections 101 and 102 created a new obligation regarding substantive

conduct. Rather, defendant argues that a statute should be

regarded as "substantive" if it will result in a remedial order,

e.g. regarding damages, that would contain an element, i.e. a "new

obligation," that would not have been contained in the order but

for the new statute at issue. Redefined in this way, "substantive"

laws would encompass virtually all the laws that were previously

regarded as remedial.

Until now the courts of appeals have repeatedly applied to

pre-existing claims new legislation providing an additional

16

monetary remedy to enforce already established prohibitions.9 In

O ’Hare v. General Marine Transport Corp., 740 F.2d 160, 170-71 (2d Cir.

1984) , this court applied to a pre-Act claim a new statute

authorizing the additional remedy of double interest and liquidated

damages. In applying Bradley v. Richmond School Board, 416 U.S. 696

(1974), this court has recognized that "simply asserting that

financial payments are unforeseen does not mean that they will

produce 'manifest injustice.'" Van Allmen v. State o f Connecticut Teachers Ret.

B d ., 613 F.2d 356, 360 (2d Cir. 1979). The only reason a plaintiff

seeks to invoke a new remedial statute, and the only reason a

defendant opposes such application, is because both believe the

statute will affect the outcome of the case. If a statute were

deemed "substantive" whenever it would affect the ultimate remedy

in a case, the century old distinction between substantive and

remedial statutes would obviously be eviscerated.

The distinction between the treatment of substantive and

remedial laws has persisted unchanged, and virtually unquestioned,

since the mid-nineteenth century. Faced with the application of

that longstanding distinction to the 1991 Civil Rights Act, the

defendant urges that a century of established precedent should now

be overturned. We believe such a change, for the sole purpose of

See e.g., Hastings v. Earth Satellite Corp., 628 F.2d 85, 92-94

(D.D.Cir. 1980) (applying to pre-Act claim law eliminating cap on

damages); Thompson v. Sawyer, 678 F.2d 257, 278-96 (D.C.Cir. 1981)

(applying to pre-Act claim law authorizing recovery of liquidated

damages); United States v. M onsanto, 858 F.2d 160, 175-76 (4th Cir. 1988)

(additional remedy of pre-judgment interest).

17

preventing application of the 1991 Act to cases such as this, would

be unjust and unwise. For a full century, in an enormous variety

of civil cases, and some criminal cases as well, the courts have

applied to pending cases new legislation regarding — i.e. changing

— available procedures and remedies. It would be indefensible to

repudiate this long line of decisions merely because the plaintiffs

who now seek to apply it are the black victims of racial

discrimination. Equally importantly, if this century of precedent

is now overturned to avoid application of the Civil Rights Act,

there will be no way to resuscitate those precedents when the

retroactivity issue arises, as it surely will, in future cases

entirely unrelated to civil rights. The controversy regarding

application of the Civil Rights Act will be over in a year or two;

the de facto abolition of the substance-remedy distinction,

advocated by defendant, would affect cases well into the next

century.

Under the circumstances of this case, defendant's objection

that the 1991 Act would "greatly expand an employer's liability"

(Appellee's Brief, p.34) is particularly unpersuasive. Defendant

argues that the Act "subjects employers to liability for damages at

common law, rather than only the lesser Title VII remedies." Id. at

33) . Some defendants, prior to the 1991 Act, may have faced

exposure only for Title VII back pay, but the defendant in this

case has always been liable to an award of damages for racial

discrimination in employment. Even under Patterson, plaintiff in this

case will be entitled to damages if she prevails on her promotion

18

claim. A city employee subject to racial discrimination in the

terms and conditions of her employment may also seek and obtain

damages in an action under 42 U.S.C. §1983.

The Supreme Court in Bradley specifically held that a statute

cannot be said to impose a new obligation where, as here, the law

merely provides an additional basis on which a particular remedy

might be awarded. Prior to the adoption of the counsel fee statute

at issue in Bradley, a fee award was already possible where a

plaintiff proved a defendant was guilty of "obstinate non

compliance with the law." 416 U.S. at 696. The statute in Bradley

liberalized the standard for awarding counsel fees requiring fee

awards in virtually any school desegregation case in which a

plaintiff prevailed on the merits. 416 U.S. at 710. In applying

the new counsel fee statute, the Supreme Court explained:

[T]here was no change in the substantive obligation of

the parties. From the outset the Board . . . under

different theories . . . could have been required to pay

attorneys' fees. . . . The availability of [the new law]

to sustain the award of fees against the Board therefore

merely serves to create an additional basis or source for

the Board's potential obligation to pay attorney's fees.

It does not impose an additional or unforeseen obligation

upon it.

410 U.S. at 721.

(4) The Legislative History of the 1991 Act

Defendant quotes three words from the President's 1990 veto

message referring to "unfair retroactivity rules" in the version of

the legislation approved by Congress in that year. (Appellee's

Brief, p.22). However, a more complete reading of the veto

19

controversy makes clear that the President objected only to the

provisions of the 1990 legislation that would have mandated the

reopening of cases in which final judgments had already been

entered.

The veto message was accompanied by a memorandum from the

Attorney General, in which the President advised Congress

"explain[ed] in detail the defects that make [the bill]

unacceptable." (136 Cong. Rec. S 16502 (daily ed. , Oct. 24,

1990)). That memorandum explained more specifically that what the

President objected to was applying the new law "to cases already

decided."10 * An earlier letter from the Attorney General had made

the same narrow point in the spring of 1990, expressing objection

to "upsetting final judgments."11 Even conservatives understood

the Attorney General's objections to be limited to final

judgments.12 Senator Hatch, who was the leading senate supporter

of the Administration, stated expressly during the veto debates

that "we" favor legislation that would overturn Patterson and be

applicable to Brenda Patterson's own pending litigation.13

10 Memorandum for the President, Oct. 22, 1990, p.10.

Letter of Attorney General Thornburgh to Senator Edward

Kennedy, April 3, 1990, p.10.

12 See H.R.Rep. 101-644, pt.2, p.7l (1990)(Additional views

of Rep. Sensenbrenner, et al).

13 136 Cong.Rec S 16565 (daily ed., Oct. 2, 1990):

"This [vetoed] bill . . . is an employer-

employee relations bill, except for the

overrule of Patterson versus McLean case which would

take care of Brenda Patterson. We are

20

(5) The Language o f the 1991 Act

In a well-seasoned recent decision, the Ninth Circuit

concluded that the plain language of the 1991 Civil Rights Act

compels the conclusion that the law is applicable to pre-Act cases.

Davis v. City and County o f San Francisco, 1992 WL 251513 (9th Cir. 1992).

The Ninth Circuit emphasized that sections 109(c) and 402(b) of the

Act expressly provided that certain provisions of the Act would not

apply to claims arising before the enactment of the statute.

These directives from Congress that in two specific

instances the Act not be applied to cases having to do

with pre-Act conduct provide strong evidence of Congress'

intent that the courts treat other provisions of the Act

as relevant to such cases.... [I]f we construed the

entire Act as applying only to post-passage conduct, we

would run afoul of what the Supreme Court has repeatedly

declared to be the "elementary canon of construction that

a statute should be interpreted so as not to render one

part inoperative." South Carolina v. Catawba Indian Tribe, Inc.,

476 U.S. 498, 510 n.22 (1986).... We would rob Section

109(c) and 402 (b) of all purpose were we to hold that the

rest of the Act does not apply to pre-Act conduct. There

would have been no need for Congress to provide that the

Act does not pertain to the pre-passage activities of the

Wards Cove Company, see Section 402(b), or of American

businesses operating overseas, see Section 109(c), if it

had not viewed the Act as otherwise applying to such

conduct.

1992 W 152513 at *14.

prepared to do that right now".

21

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, the decision of the district court

should be reversed.

C. VERNON MASON

Suite 1108

401 Broadway

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-0147

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

ERIC SCHNAPPER

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

16th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel for Plaintiff-Appellant

22

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ii

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT 1

ISSUES PRESENTED 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE 2

DISTRICT COURT DECISION 9

POINT I

PLAINTIFF'S TITLE VII CLAIMS

WERE PROPERLY DISMISSED SINCE

THE CHARGE SHE FILED WITH THE

EEOC DID NOT ALLEGE ANY

SPECIFIC ACT OF DISCRIMINATION

WITHIN THE 300-DAY LIMITATIONS

PERIOD. THIS FAILURE TO MAKE A

TIMELY CHARGE ALSO REQUIRED

DISMISSAL OF PLAINTIFF'S CLAIMS

OF DISCRIMINATION ARISING

SUBSEQUENT TO THE FILING OF THE

EEOC CHARGE. ....................................... 12

PLAINTIFF'S CLAIMS OF PROMOTION

DENIALS DO NOT STATE A CAUSE OF

ACTION UNDER 42 U.S.C. § 1981,

AS INTERPRETED BY THE SUPREME

COURT IN PATTERSON BECAUSE THE

JOBS AT ISSUE WOULD NOT HAVE

CREATED A NEW AND DISTINCT

RELATION BETWEEN PLAINTIFF AND

DEFENDANT............................................ 18

THE LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF THE

CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1991 AND

THE PRINCIPLE OF STATUTORY

CONSTRUCTION THAT CHANGES IN

SUBSTANTIVE RIGHTS SHOULD NOT

BE GIVEN RETROACTIVE EFFECT

EACH LEAD TO THE CONCLUSION

THAT THE AMENDMENTS TO 42

U.S.C. § 1981 SHOULD NOT BE

APPLIED TO THE INSTANT ACTION.......................2 0

POINT II

POINT III

CONCLUSION 36

-i-

Cases:

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Alpo Petfoods, Inc, v. Ralston

Purina Co., 913 F .2d 958

(D.C. Cir. 1990) (Thomas, J.) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Association Against Discrimination in

Employment, Inc, v. City of

BridReport, 647 F.2d 256

(2d Cir. 1981), cert, denied,

455 U.S. 988 ( 1 9 8 2 ) .............................. .. 14

Baynes v. AT&T TechnoloRies, Inc.,

No. 91-8488, 1992 WL 296716

(11th Cir. Oct. 20, 1 9 9 2 ) ............... .. 21, 22,29, 33

Bennett v. New Jersey,

470 U.S. 632 ( 1 9 8 5 ) ........................... .. 23, 39,51

Bowen v. GeorRetown University

Hospital, 488 U.S. 204 (1988) . ...................... 39, 31

Bradley v. School Board,

416 U.S. 696 (1974) .................................. 30, 31,33

Brown v. General Services

Administration, 507 F.2d 1300

(2d Cir. 1974), aff’d , 425 U.S

820 (1976)............................................. 34, 35

Counsel v. Dow, 849 F .2d

731 (2d Cir.), cert, denied,

488 U.S. 955 ( 1988 ) ....................................... 31

Davis v. City and County of_San Francisco,

No. 91-15113,1992 WL 251513

(9th Cir. Oct. 6, 1992) .............................. 21, 22,27

Fray v. Omaha World Hearld Co.,

960 F . 2d 170 (8th Cir.' 1992) ................... 21, 22,24, 26,

27, 33

Gersman v. Group Health Ass ’n, Inc.,

59 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA)

1277 D.C. Cir. Sept. 15, 1 9 9 2 ) ........................ 21, 22,

22, 27,

29, 32

• - i i -

Page

Holt v. Michigan Department of

Corrections. Michigan State

Industries, 59 Fair Empl.

Prac. Cas. (BNA) 1261

(6th Cir. Sept. 11, 1992)

Johnson v. Uncle Ben's, Inc.,

965 F .2d at 1370

(5th Cir. 1992) ...............

Johnson v. Uncle Ben's, Inc.,

965 F .2d 1363

(5th Cir. 1992) .................

Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical

Corp. v. Bonjorno,

494 U.S. 827 (1990) .............

Leake v. Long Island Jewish Medical

Center, 869 F .2d 130

(2d Cir. 1989), aff'g substantially

for reasons stated at 695 F. Supp.

1414 (E.D.N.Y. 1988) .............

Luddington v. Indiana Bell

Telephone Co., 966 F .2d

225 (7th Cir. 1992) .............

Mi H e r v. International Telephone and

Telegraph Corp., 755 F .2d 20

(2d Cir.), cert, denied,

474 U.S. 851"(1985) .............

Morgan Guaranty Trust Co. v ■

Republic of Palau,

971 F . 2d 9171" (2d Cir. 1992) . . .

Mo zee v . Ainerican Coinine r c i al

Marine Service_Co^, 963 F.2d

929 (7th Cir. 1992),

cert. denied, 61 U .S .L .W .

3261 (Oct. 5, 1992) .............

Patterson v . McLean Credit Union,

491 U.S. 164 (1989) .‘. . . .

. 21, 22,

29, 32,

33

19, 27

. 21, 22,

29, 32,

33

31

25, 32

2 1 , 2 2 ,

32, 33

13, 14,

15, 17

. . 30, 31,

33

. . 2 1 , 2 2 ,

24, 27,

28

. . . 2, 8,

18, 19,

20, 23

-in.-

Page

Smith v. American President

Lines, Ltd., 571 F .2d 102

(2d Cir. 1978 ) ............... . . . . . . 14, 16,

17

Taub, Hummel & Schnall v.

Atlantic Container Line, Ltd.,

894 F .2d 526 (2d Cir. 1990) ............. ............... 31

United Air Lines. Inc. v. Evans,

431 U.S. 553 (1977) ..................... ............... 13

United States v. Colon,

961 F .2d 41 (2d Cir. 1992) ............... ............... 31

United States v. Security

Industrial Bank, 459 U.S.

70 ( 1 9 8 2 ) ....................... .. ............... 30

Voeel v. City of Cincinnati,

959 F .2d 594 (6th Cir. 1992),

cert, denied, 61 U.S.L.W. 3257

(Oct. 5, 1992) ............................ 24, 26,

27, 33

Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio,

490 U.S. 642 (1989) ..................... ............... 27

Zipes v. Trans World Airlines, Inc.,

455 U.S. 385 (1982) ..................... ............... 13

- IV-

Statutes:

42 U.S.C. § 1 9 8 1 ..........................- ...............passim

42 U.S.C. §2000-e ( 5 ) ( a ) ( l ) ......................... .. 13

Civil Rights Act of 1991, Pub. L.

No. 102-166, 105 Stat. 1071 (1991) ................... passim

Other Authorities:

137 Cong. Rec. S15485

(daily ed. Oct. 30, 1991)

(statement of Ser. K e n n e d y ) ..................... .. 25

137 Cong. Rec. §15963

(daily ed. Nov. 5, 1991)

(statement of Sen. Kennedy) ..........................25, 28

137 Cong. Rec. S15966

(daily ed. Nov. 5, 1991)

(statements of Sers.

Gorton and Durenberger) .................................. 28

H.R. 1, 102d Cong., 1st Sess . ,

137 Cong. Rec. H3922

(daily ed. June 5, 1 9 9 1 ) .............................. 22, 23,24

H.R. Rep. No. 40(11),

102d Cong., 1st Sess.,

1991 U.S.C.C.A.N. 732 .................................... 23

S.2104, 101st Cong., 2d Sess.,

§§12, 151(a)(b), printed at

136 Cons. Rec. 59966 (daily ed.

Jul. 18, 1 9 9 3 ) ............................................. 22

Statement of President George Push

Upon Signing S.1745, 1991

U.S.C.C.A.N. 768 (Nov. 21, 1991) ......................... 26

Veto Message for S. 2104,

136 Cong. Rec. 516562

(daily ed. Oct. 24, 1990) ................................ 22

Page

- v-

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

GENEVA BUTTS,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

-against-

THE CITY OF NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF

HOUSING PRESERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT,

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States

District Court for the Southern

District of New York

APPELLEE'S BRIEF * 1

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

In this action alleging employment discrimination in

violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and 42

U.S.C. § 1981, Geneva Butts, plaintiff-appellant, appeals from a

judgment of the United States District Court for the Southern

District of New York (Freeh, D.J.), entered July 10, 1992,

granting defendant's motion to dismiss the complaint.

ISSUES PRESENTED

1. Did the District Court properly find plaintiff's

Title VII claims time-barred for failure to make a timely

complaint to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC)

where plaintiff's EEOC charge did not mention any specific act of

discrimination within the 300-day limitations period?

2. Did the District Court correctly determine that

plaintiff's allegations of discriminatory denials of promotion

failed to state a claim under 42 U.S.C. § 1981, as it was

interpreted by the Supreme Court in Patterson v. McLean Credit

Union, 491 U.S. 164 (1989), where plaintiff's amended complaint

contains no allegations concerning the duties of the positions

involved and, hence, there was no showing that the promotions at

issue would have amounted to a "new and distinct" contractual

relationship with defendant?

3. Was the District Court correct in refusing to apply

the 1991 amendments to 42 U.S.C. § 1981 where the conduct at

issue took place before the amendments were enacted and the

legislative history of the amendments demonstrates that they were

not intended to apply retroactively?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

a. Plaintiff's EEOC Charge

Plaintiff, an African-American female, has been

employed by defendant since 1972 (10a).1 In December 1989,

plaintiff, aided by counsel, filed a charge of discrimination

with the EEOC (105a). The charge begins with conclusory

assertions that plaintiff has been "denied equal terms and

conditions of employment" and promotions and that "[s]ince

October of 1987 to present, I have consistently been a target of

discriminatory practices and treatment" (10a). It then describes

the following instances of alleged discrimination: *

:Number in parentheses followed by an "a" refer to pages in

the Joint Appendix.

-2-

* In June 1987, "obvious discrimination started" when

plaintiff was named to replace Andrew Cooper, a black male, as

Acting Deputy Director of the agency’s computer center; plaintiff

alleges that Cooper had done a good job and was replaced "for no

apparent reason" (10a).

* Though plaintiff was appointed Acting Deputy

Director, she claimed that she was ignored by management and

served as "a figurehead because of my sex and race" (11a, 10a).

In May 1987, plaintiff wrote a memo to this effect to her

immediate supervisor, Fred DeJohn, suggesting that she should be

returned to her previous position as Computer Systems Manager

(lOa-lla). Five days after plaintiff's memo to DeJohn,

defendant's Commissioner sent out a memorandum stating that

plaintiff was "working closely" with DeJohn; according to

plaintiff, however, even though she was "responsible for the

entire Computer Center," from June-September 1987, her contact

with DeJohn was limited to less than ten telephone calls (11a).

* In May 1987,2 the position above plaintiff, that of

Director, was raised to the Assistant Commissioner level at a

higher salary than that of "the dismissed African-American's

manager's" (11a).3 Plaintiff complained to the EEOC that,

2The date is not specified in the EEOC charge, but appears

in plaintiff's amended complaint (100a).

3This is presumably a reference to the previously mentioned

Mr. Cooper; however, in the charge, Cooper is described as having

been Deputy Director, not Director (10a).

-3-

despite her long tenure with the agency, she "was asked to submit

a resume" if she wanted to apply for the job (11a).

* Unspecified requests for more staff were not

answered and when plaintiff proposed someone for Manager of

Operations, "as [plaintiff's] title allowed", she was told that

Acting Commissioner Sosa, a white male, would decide whom to hire

(11a). Plaintiff did not state when this occurred.

* "After October 1987," plaintiff's work was subject

to "constant scrutiny and unfair criticism" (11a). No specific

instance is mentioned. Sosa allegedly held meetings on

reorganization without telling plaintiff about the meetings or

what transpired (11a).4

* At some unspecified time, people who previously

reported to plaintiff about personnel and administrative matters

were told not to do so, and "employees were made to feel

management would not approve of their associating" with plaintiff

(12a). Again, no specifics were given.

* As of November 1989, the agency was planning to move

its computer operations in January 1990, from Harlem to lower

Manhattan, a move plaintiff alleged would reduce the level of

minority employment and "effectively [eliminate] the African-

American management base developed since the agency's existence"

(12a) .

4The allegation that she was not involved in discussions

about reorganizing the office is undated in the EEOC charge, but

the amended complaint places the events around October 1987 (11a,

98a) .

-4-

The EEOC charge finished with another series of

conclusory allegations of discrimination, referring to

unspecified occasions when plaintiff was denied bonuses and

"several requests for advancement" (12a).

b. The EEOC Determination

In May 1991, after investigation, the EEOC dismissed

plaintiff's charge (106a). The Commission found that plaintiff

could not complain about discrimination based on the proposed

relocation of the computer operations because the relocation had

not occurred (105a). Regarding plaintiff's other complaints, the

EEOC said (105a):

[T]he allegations alleged in the

affidavit of the Charging Party via

her attorney regarding terms and

conditions of employment and

promotional opportunities, occurred

during the year 1987. The Charging

Party through her attorney did not

file her charge until December 5,

1989, well beyond the 180 to 300

days filing requirement as set

forth by the statute. Therefore,

these issues are untimely, and time

barred by law.

c. The Instant Proceeding and Plaintiff's Amended Complaint

Plaintiff filed this action pro se in August 1991, and

defendant moved to dismiss "on the ground that it is time barred

and fails to state a claim" (15a). Plaintiff subsequently

obtained counsel and moved to amend her complaint (91a).

Defendant did not object to the amendment, and its motion to

dismiss was applied to the amended complaint (123a).

-5-

The amended complaint (i) contained allegations of

discrimination never mentioned in the EEOC charge even though

they allegedly occurred prior to the filing of the charge, (ii)

made no mention of some claims included in the EEOC charge, and

(iii) added allegations of discrimination occurring after the

EEOC charge was filed.

The allegations of discriminatory conduct are contained

in paragraphs 15 and 16 of the amended complaint (97a-100a).

Paragraph 15 alleged continuous discrimination against plaintiff

from May 1987 to the present in denying "equal terms and

conditions of employment" and promotions (97a). Plaintiff

asserted, without specifics, that she had been denied access to

her supervisors from "May 1987 to the present" (97a).

Plaintiff complained that in October 1987, when the

computer operations were reorganized and placed under an

Assistant Commissioner, she was effectively demoted because

people who had been her subordinates were now placed at her level

(98a). Though occurring over two years before the EEOC charge

was filed, this was not mentioned in the EEOC charge.

Similarly, plaintiff complained that the training

liaison function was taken from her in the Spring of 1988,

without explanation (98a). Though this was over a year before

the EEOC charge was filed, it, too, is not mentioned in the

charge, nor is plaintiff's allegation that, sometime in 1988,

plaintiff was improperly excluded from working with a new private

-6-

sector committee studying ways to improve City efficiency (98a-

99a) .

Plaintiff again complained about the proposed

relocation of defendant's computer operations, but, while her

EEOC charge criticized the relocation because it would allegedly

hurt minority employment, the amended complaint said that the

discriminatory conduct was excluding plaintiff from discussions

of the subject (99a).

Regarding denial of promotion opportunities, plaintiff

reiterated her allegation from the EEOC charge that, in May 1987,

she was told to submit a resume if she wanted to apply to be

Assistant Commissioner for the newly reorganized computer

operations (99a-100a). She also alleged discriminatory denial of

two other promotions, neither of which are mentioned in the EEOC

charge, even though the denials occurred before the charge was

filed (99a-200a). Plaintiff also claims discriminatory promotion

denials in May 1990 and June 1991, after the EEOC charge was

filed (99a-100a). Nothing is said about the duties of these

positions or about how they differ from her current position as a

Director.

Plaintiff's amended complaint does not reiterate the

allegations in her EEOC charge regarding supposed unfair

criticism of plaintiff's work and Sosa's alleged refusal to

accept plaintiff's recommendation for filling the operations

manager position.

-7-

d. Defendant's Motion to Dismiss

Arguing for dismissal of the complaint, defendant noted

that plaintiff was required to allege that some discriminatory

act occurred within 300 days before plaintiff filed her EEOC

charge (42a). Here, plaintiff's specific allegations of

discrimination occurred either well before the 300-day period or

after it (42a). Moreover, said defendant, plaintiff's complaints

regarding discrimination after the EEOC charge was filed

constitute new allegations of discrimination that are not

reasonably related to the incidents described in the EEOC charge

and, therefore, are not properly before the Court since they were

never the subject of a timely filing with the EEOC (46a-48a).

Regarding plaintiff's claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1981,

defendant explained that certain claims were barred by the three-

year statute of limitations (29a). In any event, defendant

continued, the alleged discriminatory acts were not actionable

under that statute as interpreted by the Supreme Court in

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 491 U.S. 164 (1989) and could

not be the basis of an action under section 1981, as amended by

the Civil Rights Act of 1991, since the amendment was not

applicable to cases already pending when it was enacted (30a-

35a) .

Plaintiff’s state-law claims were deemed legally

insufficient because of plaintiff's failure to allege compliance

with New York's notice of claim requirements (51a-52a).

-8-

Plaintiff defended the timeliness of her EEOC charge by

arguing that the conduct complained of amounts to "an on-going

pattern of discrimination" constituting a continuous violation of

Title VII (74a). Plaintiff characterized her EEOC charge as

alleging "the maintenance, by the defendant, of a system which

was calculated to deprive persons such as the plaintiff from

opportunities of advancement and to maintain a dual system of

blacks uptown in Harlem and whites downtown on Gold Street" (75a-

76a) .

Defendant countered that plaintiff did not establish a

continuing violation of Title VII because, even under the

continuing discrimination doctrine, plaintiff had to make non-

conclusory allegations to the EEOC showing specific acts of

discrimination within the 300-day limitations period (24a-26a).

Plaintiff said that her claims under § 1981 were

legally sufficient for two reasons: (i) the claims of promotion

denials were actionable under § 1981, as interpreted by the

Supreme Court in Patterson, because the promotions would have

placed plaintiff in a new relation to defendant, thus

constituting discrimination in the formation of a contract (79a-

80a) and (ii) the 1991 amendments to § 1981 should be

retroactively applied to this case (82a-84a).

DISTRICT COURT DECISION

After detailing the factual allegations of

discrimination in plaintiff's amended complaint, the District

Court turned to the timeliness of plaintiff's EEOC charge and

-9-

said that "in order to determine whether that charge was filed

within the 300-day statutory time limit, we must ascertain when

HPD committed the last allegedly discriminatory act" (126a). The

Court said it would not consider claims of discrimination in the

amended complaint unless they were asserted at the EEOC or were

"reasonably related" to claims before the EEOC (126a).

The Court found that it did not have jurisdiction over

plaintiff's complaints about being removed as training liaison in

1988 and being denied promotions in 1989, 1990, and 1991 because

they were neither brought before the EEOC nor "related to the

allegations" in the EEOC charge (127a).

The Court also found that no claim of discrimination

was stated by plaintiff's complaints about the relocation of the

computer operations since the site was never moved, nor with

regard to the promotion opportunity for which plaintiff refused

to "comply with [defendant's] reasonable reguest that she submit

a resume first" (128a, 127a-128a).

After this analysis, the Court said that "[o]mitting

[the above-mentioned] allegations, the last act of discrimination

contained in the complaint occurred in late 1987" (128a).

Discussing plaintiff's claim that a continuing violation was

shown, the Court observed that the doctrine "is disfavored in

this Circuit" and is applicable only when there are related acts,

one of which is within the limitations period or when there is a

discriminatory system in place before and during the limitations

period (128a).

-10-

While noting that the amended complaint makes

"generalized references to conduct continuing 'through the

present'", the Court found that the complaint does not show

continuous discrimination up to the time it was filed, but rather

"a number of allegedly discriminatory acts which occurred in the

past. Such discrete acts do not satisfy the continuity

requirement for a 'continuing violation'" (129a). Even if

plaintiff pleaded "a continuing series of Title VII violations",

her complaint did not show that they were related or that

defendant had any kind of "discriminatory system" in place (129a-

130a).

Regarding the claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1981, the

District Court held that the three-year statute of limitations

bars any "allegations regarding conduct prior to August 1988"

(130a). The Court also held that while plaintiff did not make

out a claim under section 1981 as interpreted in Patterson, she

did have a "valid claim for relief" under that statute as it was

amended in 1991 (131a); however, after noting that this Court had

not yet addressed the issue of whether the 1991 amendment was

retroactive, the Court said that it had already reviewed the

issue and found that the amendment "should not be applied to

pending cases" (131a). As a result, the Court said the claims

under section 1981 had to be dismissed (132a).

The Court also agreed with defendant that the state-law

claims could not be maintained since plaintiff never filed the

notice of claim required by state law (132a).

-11-

POINT I

PLAINTIFF'S TITLE VII CLAIMS WERE

PROPERLY DISMISSED SINCE THE CHARGE

SHE FILED WITH THE EEOC DID NOT

ALLEGE ANY SPECIFIC ACT OF

DISCRIMINATION WITHIN THE 300-DAY

LIMITATIONS PERIOD. THIS FAILURE

TO MAKE A TIMELY CHARGE ALSO

REQUIRED DISMISSAL OF PLAINTIFF'S

CLAIMS OF DISCRIMINATION ARISING

SUBSEQUENT TO THE FILING OF THE

EEOC CHARGE.

The District Court correctly dismissed plaintiff's

Title VII claims as untimely because they were not the subject of

an EEOC charge filed within 300 days after the occurrence of the

alleged discriminatory conduct. The only specific acts of

discrimination mentioned in plaintiff's EEOC charge occurred long

before the limitations period, and these stale allegations could

not be revived by conclusory assertions of continuing or present

discrimination without reference to any acts evidencing this

supposed discrimination. Moreover, the additional discriminatory

acts alleged in the complaint could not be used to avoid the

requirement of a timely filing with the EEOC, even if these acts

were related to past conduct mentioned in the EEOC charge.

Indeed, many of the acts alleged for the first time in the

amended complaint also occurred well before the EEOC charge was

filed and could have been included therein. Plaintiff cannot

evade the requirements of Title VII by contending that these

acts, and acts allegedly occurring after the EEOC charge was

filed, can be the basis of a lawsuit even though there was never

a timely EEOC charge of any kind.

-12-

Absent the timely filing of charges with the EEOC, a

Title VII action is time-barred. See Miller v. International

Telephone and Telegraph Corp., 755 F.2d 20, 23 (2d Cir.), cert.

denied, 474 U.S. 851 (1985) (construing virtually identical

provisions in Age Discrimination in Employment Act); see also,

Zipes v. Trans World Airlines, Inc., 455 U.S. 385, 394 (1982).

Moreover, the suit must be based on claims either raised before

the EEOC or "within the scope of the EEOC investigation

reasonably expected to grow out of" the EEOC charge. Miller, 755

F.2d at 23-24 (citations omitted). As this Court explained in

Miller, "[t]he purpose of the notice provision, which is to

encourage settlement of discrimination disputes through

conciliation and voluntary compliance, would be defeated if a

complainant could litigate a claim not previously presented to

and investigated by the EEOC." 755 F.2d at 26.

EEOC charges are untimely unless they are filed within

300 days "after the alleged unlawful employment practice

occurred". 42 U.S.C. § 2000-e(5(e )(1). Discriminatory conduct

not brought before the EEOC in a timely fashion "is merely an

unfortunate event in history which has no present legal

consequences." United Air Lines, Inc, v. Evans, 431 U.S. 553,

558 (1977).

Where, as here, a plaintiff argues that otherwise stale

complaints of discrimination constitute a continuing violation of

Title VII and are therefore timely, the Supreme Court has said

that "the emphasis should not be placed on mere continuity; the

-13-

critical question is whether any present [Title VII] violation

exists." Evans, 431 U.S. at 558 (emphasis in original).

Accordingly, this Court has explained that a plaintiff alleging a

continuous violation of Title VII must show that the EEOC charge

was "filed no later than 300 days after the last act by the

defendant pursuant to its policy" of discrimination. Association

Against Discrimination in Employment, Inc, v. City of Bridgeport,

647 F .2d 256, 274 (2d Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S. 988

(1982) (emphasis in original). Moreover, the allegations that a

defendant is engaged in a continuous pattern of discrimination

must "be clearly asserted both in the EEOC filing and in the

complaint." Miller, 755 F.2d at 25.

These requirements are not met by conclusory assertions

that past discriminatory conduct is continuing into the

limitations period. To determine if a plaintiff has made a

timely EEOC filing alleging a Title VII violation within the

limitations period, a court must "identify precisely" the

discriminatory conduct complained of. Delaware State College v.

Ricks, 449 U.S. 250, 257 (1980). The plaintiff must be able to

point to "events" showing that there was "a continuing pattern of

identifiable discriminatory conduct." Smith v. American

President Lines, Ltd., 571 F.2d 102, 106 (2d Cir. 1978); compare

Smith, 571 F.2d at 106 (EEOC charge untimely where "no reference

at all to any event" during period of alleged continuing

violation), with, Association Against Discrimination, 647 F.2d at

275 (continuing violation found where "district court made

-14-

express findings as to several discriminatory acts by the City

[of Bridgeport] that occurred within" the 300-day limitations

period).

The District Court correctly found that the

discrimination alleged in the complaint was not the subject of a

timely EEOC charge. Since the EEOC complaint was filed in

November 1989, any alleged discriminatory conduct occurring

before January 1989 is outside the 300-day limitations period.5

With one exception, all of the allegations in paragraph 15 of the

complaint relate to events that occurred in 1987 and 1988. The

only exception is in paragraph 15(e), where plaintiff says that,

from 1987 through 1990, she was kept out of discussions

concerning the computer operation's relocation from Harlem to

lower Manhattan. However, this claim was not presented to the

EEOC at all; there, plaintiff's complaint about the relocation

was that, if the computer operations were moved, it would

adversely impact on minority employment.6 The failure to raise

this claim with the EEOC bars raising it in court. See Miller,

755 F.2d at 25 (cannot consider claim of failure to rehire where

5The EEOC determination said that the charge was not filed

until December 5, 1989 (105a) and the charge itself is stamped

March 9, 1990 (13a). However, the District Court used the

November 22, 1989 date, when plaintiff's charge was notarized by

her attorney, and this is the date most beneficial for plaintiff

(126a) .

6Plaintiff did complain to the EEOC about not being

consulted on various matters, but that complaint was based on

events in 1987, well before the limitations period (supra at 3).

-15-

the plaintiff's complaint to EEOC alleged only discriminatory

discharge from employment).

Paragraph 16 of the amended complaint refers to denials

of promotions in 1987, 1989, 1990, and 1991. However, the EEOC

charge only mentions one promotion denial, in 1987, and

plaintiff's grievance over that "denial" was that the agency

required submission of a resume to apply for the job, an

Assistant Commissioner's position.7 The District Court

correctly found that these allegations failed to state a claim of

discrimination as a matter of law. Defendant was entitled to ask

for a resume from people seeking the Assistant Commissioner's

position, and plaintiff made no allegation that the request was

made only of her or on any invidious basis.

Plaintiff tries to revive the stale allegations in her

charge by relying on events subsequent to the filing of the EEOC

charge and pre-charge events never mentioned in the EEOC charge,

arguing that these allegations can be considered because they are

reasonably related to the claims made in the EEOC charge (Applt.

Br. at 4-9). This cannot be done.

While a Title VII action can include "subsequent

identifiable acts of discrimination related to a time barred

incident", this principle only applies if the plaintiff has

7The EEOC charge does allege that plaintiff was denied

"several requests for advancement", but it gives neither dates

nor other specifics (12a). This type of conclusory assertion is

legally insufficient because it is not an allegation of an

"event" of "identifiable discriminatory conduct." Smith, 571

F .2d at 106.

-16-

either "filed an amended or second charge with the EEOC which was

timely as to subsequent discriminatory conduct by the defendant,

or had filed an initial charge within the time frame of § 2000-

e(5)(e) as to certain enumerated acts within an alleged

discriminatory pattern." Smith, 571 F.2d at 105 (footnote

omitted).

The reason for this rule is obvious. While it would be

improper to require a Title VII plaintiff to make repeated trips

to the EEOC to bring suit on subsequent acts of discrimination

that are related to past discrimination that was presented to the

EEOC in a timely fashion, it would defeat the statutory purpose

if a plaintiff could skip the EEOC process entirely by taking new

discrimination claims into court without ever having made a

timely complaint of any kind to the EEOC. Miller, 755 F.2d at

26 .

Here, plaintiff did not file an amended EEOC charge

enumerating the subsequent events, nor, as explained above, did

she file a timely charge regarding the earlier events that are

supposedly related to the subsequent conduct. Indeed, the 1988

promotion denial alleged in the amended complaint happened well

before the EEOC charge was even filed and should have been

included therein. Plaintiff cannot correct this defect by

arguing that it is related to other events that were included in

the charge.

-17-

POINT II

PLAINTIFF'S CLAIMS OF PROMOTION

DENIALS DO NOT STATE A CAUSE OF

ACTION UNDER 42 U.S.C. § 1981, AS

INTERPRETED BY THE SUPREME COURT IN

PATTERSON BECAUSE THE JOBS AT ISSUE

WOULD NOT HAVE CREATED A NEW AND

DISTINCT RELATION BETWEEN PLAINTIFF

AND DEFENDANT.

Plaintiff incorrectly argues that her § 1981 claims

concerning promotion denials occurring within three years of the

filing of this action should not have been dismissed because

there was no factual determination as to whether the promotions

would have created a "new and distinct relation" between

plaintiff and defendant, thus making them actionable under § 1981

as interpreted by the Supreme Court in Patterson v. McLean Credit

Union, 491 U.S. 164, 185 (1989) (citation omitted) (Applt. Br. at

9-12).8 Since plaintiff made no effort to plead facts

indicating that the Patterson criteria were satisfied, the claims

were properly dismissed.

Prior to its amendment in 1991, the Supreme Court ruled

that 42 U.S.C. § 1981 applied only to employment discrimination

arising "at the initial formation of the contract and conduct

which impairs the right to enforce contract obligations through

legal process"; complaints of discrimination in the terms and

conditions of employment were not actionable. 491 U.S. at 179-

BPlaintiff acknowledges here, as she did in the District

Court, that the statute of limitations bars her from raising any

§ 1981 claims regarding promotion denials that occurred over

three years before this action was commenced (Applt. Br. at 9;

130a).

-18-

180, 178-180. Applying this principle to claims of

discrimination in making promotions, the Court said that (491

U.S. at 185):

the question whether a promotion

claim is actionable under § 1981

depends upon whether the nature of

the change in position was such

that it involved the opportunity to

enter into a new contract with the

employer. If so, then the

employer's refusal to enter the new

contract is actionable under

§ 1981. . . . Only where the

promotion rises to the level of an

opportunity for a new and distinct

relation between the employee and

the employer is such a claim

actionable under § 1981 (citation

omitted).

As plaintiff concedes, not every promotion meets this

criterion (Applt. Br. at 10-11). Only those involving

significant changes in job responsiblities will qualify. See

Johnson v. Uncle Ben's, Inc., 965 F.2d at 1370-1 (5th Cir. 1992).

Accordingly, to state a claim, a complaint should plead facts

that would allow a comparison between the plaintiff's present job

and the responsibilities of the promotional position. That was

not done here. Plaintiff acknowledges that, "[t]he nature of the

promotions is not disclosed by the record" (Applt. Br. at 11).

The amended complaint refers only to job titles, and while these

titles sound as if the jobs involve considerable responsiblity,

plaintiff already had a responsible position. It was incumbent

on plaintiff to plead the facts supporting her claim, and it was

-19-

proper to dismiss this cause of action in light of her failure to

do so.

POINT III

THE LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF THE

CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1991 AND THE

PRINCIPLE OF STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION

THAT CHANGES IN SUBSTANTIVE RIGHTS

SHOULD NOT BE GIVEN RETROACTIVE

EFFECT EACH LEAD TO THE CONCLUSION

THAT THE AMENDMENTS TO 42 U.S.C. §

1981 SHOULD NOT BE APPLIED TO THE

INSTANT ACTION.

On November 21, 1991, the Civil Rights Act of 1991

became law. Pub. L. No. 102-166, 105 Stat. 1071 (1991)

(hereinafter referred to as "the Act"). Among its sweeping

changes was a substantial revision of 42 U.S.C. § 1981 that

altered the prior statute, as interpreted by the Supreme Court in

Patterson. Unlike the pre-Act version, the amended § 1981

prohibits race discrimination regarding "the enjoyment of all

benefits, privileges, terms, and conditions of the contractual

relationship," not just in the formation and enforcement of

contracts. Act, § 101(b), 105 Stat. at 1072 (codified at 42

U.S.C. § 1981[b ]).

Plaintiff argues that the Act should apply here (Applt.

Br., Pt. III). However, the legislative history of this highly

controversial enactment demonstrates that, while many in Congress

wanted retroactive application of the statute, retroactivity was

surrendered in order to pass a bill that would be signed by the

President. If this Court disagrees with this assessment, it

should nonetheless reject plaintiff's argument that an intent to

-20-

apply the Act retroactively is shown. As a result, even under

general principles of statutory construction, the § 1981

amendments should be held applicable only prospectively.

The Act states that it "shall take effect upon

enactment." Act, §402(a), 105 Stat. at 1099. Several Circuit