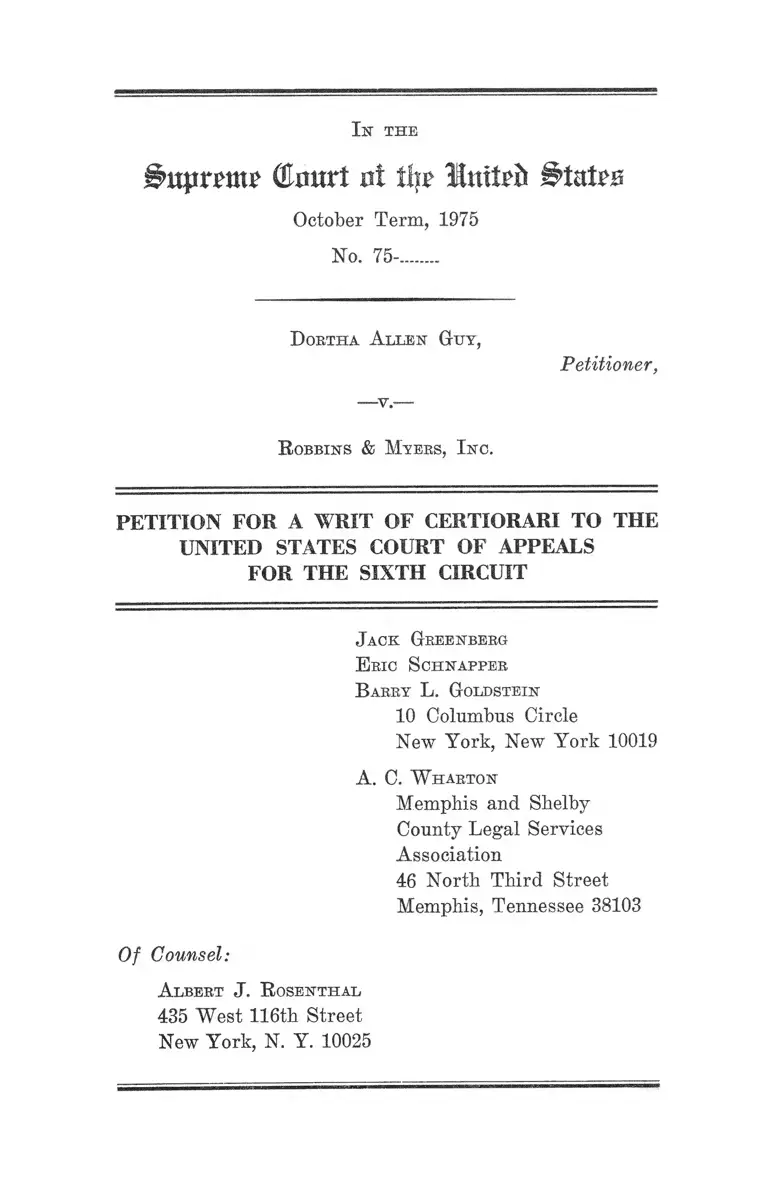

Guy v. Robbins & Myers, Inc. Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Guy v. Robbins & Myers, Inc. Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, 1975. a6558908-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/430a81a0-6dd3-4dd9-a9e0-e7b110cad61a/guy-v-robbins-myers-inc-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-sixth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I k t h e

irem? (Emtrt ut tip? Htutpfc 0tatiw

October Term, 1975

No. 75-.......

D ortha A l len Guy ,

Petitioner,

—v_

R obbins & M yers, I no .

PETII ION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

J ack Greekberg

E ric S ch n a pper

B arry L. G oldstein

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A. C. W harton

Memphis and Shelby

County Legal Services

Association

46 North Third Street

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Of Counsel:

A lbert J . R osenthal

435 West 116th Street

New York, N. Y. 10025

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Authorities ...................................................... i

Opinions Below ........................... 1

Jurisdiction .................................... 2

Question Presented ........................................... 2

Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 2

Statement of the Case ........................................... 4

Reasons for Granting the W rit.................. 7

I. The Decision Below Is in Conflict With the Deci

sions of Other Courts of Appeals on the Same

Matters ........................................... 8

II. The Case Presents an Important Question of Fed

eral Law Which Should Be Settled by This Court 12

Conclusion...................................... 17

Appendix—•

Opinion of the District Court, June 12,1974 .......... la

Opinion of the District Court, June 19, 1974 .......... 6a

Opinion of the Court of Appeals, October 24,1975 .. 11a

Order ............................................................ 23a

Table of Authorities

Cases:

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) .... 14

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974)

5, 8,16-17

PAGE

11

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 416

U.S. 696 (1974) .......... ............. ........... .................. ....11,16

Brown v. General Services Administration, No. 74-768

cert, granted, 421 U.S. 987 (1975) ............................ 7,18

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Company, 421 F.2d 888

(5th Cir. 1970) ............ ................ ' ............... .............. 8, 9

Davis v. Valley Distributing Co., 522 F.2d 827 (9th

Cir. 1975) ....................................... ................ .......... 11,12

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) .......... 14

Hutchings v. United States Industries, Inc., 428 F.2d

303 (5th Cir. 1970) .............................. ............ ......... 8,17

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S.

454 (1975) ........... ........................... ................ ....... ...16,17

Laffey v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 321 F. Supp. 1041

(D. D.C. 1971) ........... ............ ......................... ........... 13

Love v. Pullman Corp., 404 U.S. 522 (1972) .......... 9,11,15

Malone v. North American Rockwell Corporation, 457

F.2d 799 (9th Cir. 1972) ........... ...... ......................... 8, 9

McDonald v. Santa Fe Transportation Company, No.

75-260 cert, granted 46 L.Ed.2d 248 (Nov. 3, 1975) ..7,18

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973) 5

Moore v. Sunbeam Corp., 459 F.2d 811 (7th Cir. 1972) 9

Phillips v. Columbia Gas of West Virginia, Inc., 347

F. Supp. 533 (S.D. W.Va. 1972), aff’d 474 F.2d 1342

(4th Cir. 1972) ........................................................... 9

Place v. Weinberger, No. 74-116, cert, denied, 419 U.S.

1040 (1974), Petition for Rehearing pending ...........7,18

PAGE

Ill

Reeb v. Economic Opportunity Atlanta, Inc., 516 F.2d

PAGE

924 (5th Cir. 1975) ...................................................... 9

Sanchez v. Trans World Airlines, Inc., 499 F.2d 1107

(10th Cir. 1974) ......................................................... 8

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of Durham,

393 U.S. 268 (1969) .................. ................................ 16

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ........... ........................... ...... ........... 2

29 U.S.C. § 206(d)(1) .................................................... 13

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ................ ................................. .......4, 5,17

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000(e) et seq (Title VII, Civil Rights

Act of 1964) ............................................................Passim

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(d) .................................................. 2

42 U.S.C. § 2000(e)-5(e) .............................................. 3,10

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(f) ..... 13

Section 14 of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act

of 1972, 86 Stat. 103 ...............................................3, 4,11

Other Authorities:

118 Cong. Rec. 7167 (March 8, 1972) ............................ 15

H.R. Rep. No. 92-238, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 3 (1971) ...... 11

S.Rep. No. 92-415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 6 (1971) .......... 11

EEOC Decision No. 70-675, March 31, 1970, CCH

EEOC Dec. TT 6142 (1973), CCH Empl. Prac. Rep.

If 2325.123 .................................................................... 14

EEOC Decision No. 71-687, Dec. 16, 1970, CCH EEOC

Dec. 11 6186 (1973), CCH Empl. Prac. Rep. 1f 2325.302 14

I n t h e

8>npxmw Court of tip HUnxtxb B M xb

October Term, 1975

No. 75-.......

D ortha A l len Gu y ,

—v.—

R obbins & M yers, I n c .

Petitioner,

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

The petitioner respectfully prays that a writ of certiorari

issue to review the judgment and opinion of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit entered in

this proceeding on October 24,1975, rehearing and rehearing

en banc having been denied December 9, 1975.

Opinions Below

The decision of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Sixth Circuit and the order denying the petitions for

rehearing and rehearing en banc of the petitioners herein,

reported at 525 F.2d 124, are reprinted infra at 11a and

23a.1 The memorandum opinion and order of the United

States District Court for the Western District of Tennessee

dismissing plaintiff’s action and its order adhering thereto

on reconsideration, reported at 8 E.P.D. TTTT 9573 and 9574,

are reprinted infra at la and 6a, respectively.

1 This form of citation is to pages of the Appendix.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment and opinion of the Court of Appeals was

entered on October 24, 1975. The petitioner’s petition for

rehearing and rehearing en banc were denied on December

9, 1975. Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Question Presented

Petitioner’s employer discharged her on October 25, 1971.

On October 27, 1971, a union grievance was filed on her

behalf, which was denied on November 18, 1971. February

10, 1972, 108 days after her discharge, but only 84 days

from denial of her grievance, petitioner filed a Title VII

charge with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion alleging racial discrimination.

Did the Court of Appeals err in dismissing this Title VII

action on the ground that the charge which petitioner filed

with the EEOC was untimely?

Statutory Provisions Involved

Section 706(d) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat.

241, 260, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(d) (1970), before its amend

ment in 1972, read as follows:

(d) A charge under subsection (a) shall be filed

within ninety days after the alleged unlawful employ

ment practice occurred, except that in the case of an

unlawful employment practice with respect to which

the person aggrieved has followed the procedure set

out in subsection (b), such charge shall be filed by the

person aggrieved within two hundred and ten days

3

after the alleged unlawful employment practice oc

curred, or within thirty days after receiving notice

that the State or local agency has terminated the pro

ceedings under the State or local law, whichever is

earlier, and a copy of such charge shall be filed by the

Commission with the State or local agency.

The same provision, as amended by Section 4(a) of the

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, 86 Stat. 103,

105, and renumbered Section 706(e), 42 TJ.S.C. § 2000e-5(e)

(Supp. II 1972), reads as follows:

“(e) A charge under this section shall be filed within

one hundred and eighty days after the alleged unlaw

ful employment practice occurred and notice of the

charge (including the date, place and circumstances

of the alleged unlawful employment practice) shall be

served upon the person against whom such charge is

made within ten days thereafter, except that in a case

of an unlawful employment practice with respect to

which the person aggrieved has initially instituted pro

ceedings with in State or local agency with authority

to grant or seek relief from such practice or to insti

tute criminal proceedings with respect thereto upon

receiving notice thereof, such charge shall be filed by

or on behalf of the person aggrieved within three hun

dred days after the alleged unlawful employment prac

tice occurred, or within thirty days after receiving

notice that the State or local agency has terminated

the proceedings under the State or local law, which

ever is earlier, and a copy of such charge shall be filed

by the Commission with the State or local agency.”

Section 14 of the Equal. Employment Opportunity Act

of 1972, 86 Stat. 103, 113, reads- as follows:

4

The amendments made by this Act to section 706 of

the Civil Bights Act of 1964 shall be applicable with

respect to charges pending with the Commission on

the date of enactment of this Act [March 24, 1972] and

all charges filed thereafter.

Statement o f the Case

The petitioner, Dortha Allen Guy, brought this action

under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended

by the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, 42

U.S.C. § 2000e et seq., and the Civil Eights Act of 1866,

42 U.S.C. § 1981. Mrs. Guy’s complaint, brought against

her former employer, respondent Robbins & Myers, Inc.

(the Company), and her labor union, Local 790 of the In

ternational Union of Electrical, Machine and Radio Work

ers (the Union), alleged that the Company had discrim

inated against her because of her race (black), both in dis

charging her and in failing to reinstate her, and that the

Union had not fairly represented her in grievance pro

ceedings.

Mrs. Guy was discharged from her employment on Oc

tober 25, 1971. Two days later, on October 27, 1971, she

caused a grievance to be filed on her behalf,3 pursuant

to the provisions of the collective bargaining agreement

between the Company and the Union. The grievance stated:

“Protest unfair action of company for discharge. Ask that

she be reinstated with compensation for lost time.” It

was unsuccessfully carried through the third step of the 2

2 Plaintiff wa's absent from work from October 24, 1971 until

October 29, 1971, and thus was not present on the day of her dis

charge. One of her co-workers filed the grievance on her behalf.

When plaintiff returned to work on October 29, 1971, she imme

diately began personally processing the grievance through the'

various steps of the grievance-arbitration process.

5

grievance process, where it was denied in writing by the

Company’s Personnel Director on November 18, 1971. The

denial simply stated that the appellant had been right

fully discharged. Plaintiff did not press this grievance

beyond the third step, and the Union accordingly did not

take appellant’s claim to arbitration.3

On February 10, 1972, 108 days after her discharge but

only 84 days following the denial of her grievance, Mrs.

Guy filed a charge with EEOC, alleging racial discrimina

tion in her discharge. EEOC accepted and processed her

charge, and informed her on November 20, 1973 that it had

found no reasonable cause to believe that her discharge

was racially motivated4 and giving her formal notice of

her rights to sue under Title VII. She then instituted an

action against the Company and the Union in the United

States District Court for the Western District of Ten

nessee.

However, by Order of June 12, 1974, the District Court

granted the Company’s motion to dismiss5 6 plaintiff’s Title

VII allegations on the ground that plaintiff had not filed

her charge of discrimination within the 90-day period pre

3 The four Steps provided for in the Collective Bargaining Agree

ment (Article XVIII-Grievance Procedure) follow lines that are

fairly common in such agreements. Step 1 provides for proceed

ings between the employee and his foreman, Step 2 between the

Chief Steward and the General Foreman, Step 3 between the

Union Officers and representatives of Management, and Step 4

for arbitration.

4 A finding of no reasonable cause is not a bar to a Title VII

action. McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 798

(1973) ; Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 48, n. 8

(1974) .

6 The district court had earlier dismissed the case, insofar as it

was grounded on 42 U.S.C. § 1981, because of the applicable Ten

nessee statute of limitation.

6

scribed by Section 706(d) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

before its amendment in 1972. The Court further held

that the 90-day period had not been tolled during the

processing of her grievance (la-5a). On June 19, 1974, the

District Court refused to modify its prior holdings (6a-lQa).

Subsequently, the defendant Union was realigned as a

party plaintiff, Mrs. Guy and the Union filed timely No

tices of Appeal to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit, and EEOC appeared in support of

their appeal as amicus curiae.

The Court of Appeals affirmed the dismissal of the

complaint on October 24, 1975, by a 2-1 vote (lla-22a)

and denied petitioner’s petition for rehearing and rehear

ing en banc on December 9, 1975 (23a).

The Court of Appeals (1) held that Mrs. Guy by filing

her Union grievance did not toll the running of the Title VII

statute of limitations for filing a charge with the EEOC;

(2) implicitly held that the statute of limitations for filing

a charge with the EEOC began to run on the day that peti

tioner was initially dismissed, even though the company’s

decision did not become final until the completion of the

grievance process; and (3) held the 1972 amendments to

Title VII, insofar as they extended the period for filing

EEOC charges from 90 to 180 days, should not be applied

to cases which arise before the amendment but which were

still pending on the effective date of those amendments.

7

Reasons for Granting the Writ

The question presented raises three important issues

concerning the implementation of Title YII by the courts

and by the EEOC. The Sixth Circuit’s decision regarding

each of these issues is in conflict with the decisions of

other courts of appeals. All three of the issues in con

flict are now directly before the Court in McDonald v. Santa

Fe Transportation Company, No. 75-260, cert, granted,

46 L.Ed 2d 248 (Nov. 3, 1976).6 The issue in conflict con

cerning the application of the 1972 amendments to litiga

tion pending as of the effective date of those amendments

is before this Court in a closely analogous form in Brown v.

General Services Administration, No. 74-768, cert, granted,

421 U.S. 987 (1975) and Place v. Weinberger, No. 74-116,

cert, denied, 419 U.S. 1040 (1974), Petition for Rehear

ing pending.7

6 In order to reach the question presented in McDonald, whether

a white employee may raise a claim of race discrimination under

Title YII, it must be determined that the statutory period for

filing a charge with the EEOC was tolled pending grievance pro

ceeding's and that the 1972 amendment to Title VII extended the

period of time within which to file a charge with the EEOC from

90 to 180 days to all pending litigation. See Brief Amicus Curiae

of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., at p. 2.

If the Court determines either that the statute of limitation is

tolled during the processing of a grievance or that the 180 day

provision applies to pending charges, then the Guy decision must

be reversed.

7 Both Brown and Place present the question, inter alia, whether

the 1972 amendments to Title YII, insofar as they create new

remedies for federal employees, should be applied to cases still

pending on the date when the amendments become effective.

8

I.

The Decision Below Is in Conflict With the Decisions

of Other Courts of Appeals on the Same Matters.

A.

The Sixth Circuit’s holding that the filing of a union

grievance does not toll the running of the time period

for filing a Title YII charge conflicts with decision of

three other circuits.8 The Fifth,9 Ninth10 11 and Tenth Cir

cuits11 have all held that the time within which an ag

grieved person might file Title VII charges with EEOC

8 In this case the Sixth Circuit held “ [i] t would therefore ap

pear to us to be utterly incongruous for us to hold that a federal

statute which contains jurisdictional prerequisites for the exer

cise of its remedies is tolled by the mere filing of a grievance

under a collective bargaining agreement”. 17a and 525 F. 2d at

128.

9 “We, therefore, hold that the statute of limitations . . . is

tolled once an employee invokes his contractual grievance rem

edies in a constructive effort to seek a private settlement of his

complaint.” (footnote omitted) Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Com

pany, 421 F.2d 888, 891 (5th Cir. 1970) ; see also IlutcMngs V.

United States Industries, Inc., 428 F.2d 303, 312 (5th Cir. 1970).

10 “Since Title VII seeks to utilize private settlement as an ef

fective deterrent to employment discrimination, we hold that the

210-day statute of limitations is tolled while an employee in good

faith pursues his contractual grievance remedies in a constructive

effort to obtain a private settlement”. Malone v. North American

Rockwell Corporation, 475 F.2d 799, 781 (9th Cir. 1972).

11 Sanchez v. Trans World Airlines, Inc., 499 F.2d 1107, 1108

(10th Cir. 1974). In Sanchez, which was decided after Alexander

v. Gardner-Denver Corp., 415 U.S. 36 (1974), the Tenth Circuit

argues that the tolling rule was “in tune with the construction

given by the Supreme Court and other federal courts to this kind

of provision,” , id. The Tenth ■ Circuit’s interpretation of the ap

plicable Supreme Court decisions contradicts the interpretation of

the Sixth Circuit, 17a and 525 F.2d at 128. - - ■

9

was tolled for the preiod during which contractual griev

ance proceedings were being pursued.12

B.

There is an additional, related, but slightly different,

conflict between the court below and the Seventh Circuit.

The Sixth Circuit implicitly held that the period of lim

itations commences from the date of the discharge, rather

than the date on which grievance proceedings ended and

the company’s decision to fire Mrs. Guy became final. In

Moore v. Sunbeam Corp., 459 F.2d 811 (7th Cir. 1972),

the court took the opposite approach, and computed the

statutory period within which charges might be filed with

EEOC from the date on which grievance proceedings con

cluded.13 Id. at 826-27 and n. 40.

12 The court below characterizes the 90-day limitation period on

filing of charges with EEOC as an integral part of the right created

by Title VII rather than as a statute of limitations subject, to such

equitable considerations as tolling in appropriate situations. This

interpretation is inherently in conflict with the decisions of the

Fifth, Ninth and Tenth Circuits cited above, as well as with the

Seventh Circuit case of Moore v. Sunbeam Corp., 459 F.2d 811

(1972), referred to below. This characterization was also specifi

cally considered and rejected in Beeb v. Economic Opportunity

Atlanta, Inc., 516 F.2d 924, 929 (1975), and seems totally incon

sistent with the decision of this Court in Love v. Pullman Co.,

404 U.S. 522 (1972).

13 Although perhaps technically not a holding of the court, since

the computation led to the conclusion that despite the extension

of the period during which he might have filed, the plaintiff was

nevertheless too late, the opinion clearly established the law of

the Seventh Circuit on the subject.

See also Phillips v. Columbia Gas of West Virginia, Inc., 347

F. Supp. 533, 538 (S.D. W. Va. 1972), affirmed w.o. op., 474

F.2d 1342 (4th Cir. 1972), treating the statutory time as starting

to run upon the conclusion of the grievance proceedings, but dis

missing the charge on other grounds. The analysis adopted in

Moore v. Sunbeam Corp., supra, had also been advanced in Cul

pepper v. Reynolds Metals Co., supra, but not passed upon in that

case because the decision that the limitation had been tolled made

it unnecessary to do so. 421 F.2d at 893, n. 5. See also, Malone

v. North American Rockwell Corp., supra, 457 F.2d at 781, n. 2.

10

The approach of the Seventh Circuit in Moore is in turn

in conflict with the decisions of the Fifth, Ninth and Tenth

Circuits. Under the tolling approach of the Fifth, Ninth

and Tenth Circuits the statute would have been tolled dur

ing the 22 days of Mrs. Guy’s grievance proceedings, from

October 27 through November 18, 1971. Since Mrs. Guy

filed her charge on the 108th day after her discharge, her

charge under this approach would have been construed as

being filed on the 86th day and therefore timely. If the

Seventh Circuit approach had been applied, the statute

would have started running on November 18,1971 (the date

of the final resolution of the grievance). The filing by

Mrs. Guy of an EEOC charge on February 10, 1972, 84

days later, would have again been held timely. Thus, if

the Sixth Circuit had followed either of the alternatives

adopted by the other circuits, Mrs. Guy’s complaint would

not have been dismissed. However, the conflict between

the approaches of the Seventh Circuit and that of the Fifth,

Ninth and Tenth Circuits, may sometimes cause a different

result. For example, if Mrs. Guy had filed her charge on

February 15, 1972 (rather than February 10, 1972), the

charge would have been construed as being filed on the

89th day pursuant to the approach of the Seventh Circuit

and thereby timely; however, pursuant to the approach of

the Fifth, Ninth and Tenth Circuits the charge would have

been construed as being filed on the 91st day and thereby

untimely.

C.

The court of appeals also refuses to apply to this case

the 1972 amendments to Title VII, even though this case

was still pending on the date when the amendments became

effective (17a, 525 F. 2d at 128). The 1972 amendment ex

tended the period in which an EEOC charge must be filed

from 90 to 180 days, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(e). As Judge Ed

11

wards noted in Ms dissent (19a-20a), this decision is

squarely, in conflict with the decision of the Ninth Circuit

in Davis v. Valley Distributing Go., 522 F, 2d 827 (1975),

which held that the 180-day rule must be applied to such

pending cases. The decision in the instant ease, is clearly

inconsistent with the rule reaffirmed by this Court in Brad

ley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 416, IT.8. 696,

711 (1974), “that a court is to apply the law in effect at

the time it renders its decision, unless there doing so would

result in manifest injustice or there is statutory direction

or legislative history to the contrary.” 14

The decision in this case as to the applicability of the

1972 amendments to pending charges is also inconsistent

with Love v. Pullman Co., 404 U.S. 522 (1972), where this

Court refused to apply technicalities, such as a formal

istic double filing of charges of discrimination, to the pro

cedures which are undertaken by laymen under Title VII.15

14 Here the statute specifically mandates the application of the

amendments to pending charges, Section 14 of the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Act of 1972; 86 Stat. 103, 113.

The question of the applicability of the 1972 amendments to

previously filed charges is independently important, in the light

of the huge number of charges that were being filed every year

with EEOC, and the large backlog of charges on which EEOC

had not completed processing and which were still pending at the

time of the enactment of the amendments. See H.R. Rep. No.

92-238, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 3 (1971); S. Rep. No. 92-415, 92d

Cong., 1st Sess. 6 (1971).

15 Gf. Love v. Pullman Co., 404 U.S. 522 (1972), in which a

charge had been filed prematurely with EEOC before submission

to a state anti-discrimination agency, contrary to the statutory

requirement that where there was such a state agency charges were

to be filed with EEOC only after the expiration of certain time

period's following filing with the state agency. After completion

of the state proceedings, EEOC assumed jurisdiction over the

charge without requiring a second filing, and this Court upheld its

practice. The Court stated:

. . > To require a second “filing” by the aggrieved party after

termination of state proceedings would serve no purpose other

12

In both the instant case and the Davis case, the plaintiffs

were discharged more than 90 but less than 180 days before

they filed charges with EEOC. In both cases, charges were

filed before March 24, 1972, the effective date of the 1972

amendments to Section 706 of the 1964 Act (the section

including the time requirements for filing of charges with

EEOC). In both cases the discharge had occurred less

than 180 days before March 24, 1972; therefore in both

cases, if the plaintiffs had engaged in the ridiculously

superfluous act of re-filing with EEOC on or shortly after

March 24, 1972, their position would have been immune

to challenge. The Ninth Circuit, in the Davis case, refused

to stultify the law by holding that an aggrieved party would

forfeit his claim by failing to file a second, redundant

charge.16 The Sixth Circuit, in the instant case, held the

opposite way.

II.

The Case Presents an Im portant Q uestion o f Federal

Law W hich Should Be Settled by This Court.

This case involves important and frequently recurring

questions arising out of the interrelationship between the

Congressional policies forbidding employment discrimina

tion and those encouraging utilization of grievance-arbitra

tion procedures.

than the creation of an additional procedural technicality,

such technicalities are particularly inappropriate in a statu

tory scheme in which laymen, unassisted by trained lawyers,

initiate the process. (404 U.S. at 526-27)

16 We should point out that Davis might be distinguished on

the ground that there was a technical new “filing” by EEOC it

self of plaintiff’s late charge following remand from a state agency,

just before March 24, 1972. But this scarcely weakens the main

thrust of the Davis holding, that the retroactive provision in the

1972 amendments was intended to apply, inter alia, to previously

filed charges, thus modifying the time within which those charges

had to be filed with EEOC.

13

The conflict among the circuits is an irresistible invita

tion to forum-shopping. The venue provision of Title YII

provides that a suit may be filed in several alternative

jurisdictions.17 Until this Court acts, Title VII plaintiffs

will, or will not, lose their Title VII rights depending not

only on the happenstance of the state in which they work,

but also depending on the resourcefulness of their lawyer

to select the jurisdiction with the “proper” tolling deci

sions.18 Because many major employers and unions oper

ate nationwide, venue often exists in several different cir

cuits.19

This conflict poses serious administrative problems for

the EEOC. The EEOC must apply different rules as to

whether a charge should be deemed timely and accepted

according to the circuit involved. Where, as is common,

venue would lie in several different circuits with different

rules, the EEOC will have to resolve complex problems of

conflict of laws. EEOC has heretofore repeatedly held that

the statutory limitations on the time within which charges

17 The plaintiff may bring his Title YII action in the district

where the unlawful act is alleged to have been committed, where

plaintiff would have worked but for the alleged practice or where

employment records pertaining to the unlawful practice are main

tained and administered, or if the putative employer or union is

not found within any such district, a Title VII action may be

brought within the judicial district in which he has his principal

office, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(f).

18 Of course, counsel may devise many theories for selecting the

jurisdiction in which there is an “appropriate” rule on “tolling.”

Cf. Laffey v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 321 F. Supp. 1041 (D.

D.C. 1971). (Because the plaintiff joined a cause of action under

Title VII with a cause of action under the Equal Pay Act of 1963,

29 U.S.C. §§206 (d) (1), et seq., the district court held that the

general venue provision for federal courts applied.)

19 Often, as is the case for a plaintiff like Mrs. Guy who lives in

Memphis, it is convenient to bring an action in a number of cir

cuits. I t is only a short drive from Memphis to either the Eighth

or the Fifth Circuits.

14

might be filed with it were tolled during the prosecution

of grievance proceedings, and that where the timeliness

of the charges depended upon such tolling EEOC had

authority to process them and, if conciliation was not

achieved, to authorize the charging parties to commence

suit in district court pursuant to Title VII.20 EEOC in

terpretations of Title VII are, of course, entitled to great

deference. Griggs v. Duke Power C o 401 U.S. 424, 433-34

(1971); Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 431

(1975). If the court does not resolve the conflicts between

the circuits, the EEOC will be confronted with the bureau

cratic tangle of processing charges of discrimination ac

cording to the state in which they arise.21

The other circuits have permitted tolling of the period

for filing of charges with EEOC while grievance proceed

ings were being pursued, in order to protect against in

advertent loss of Title VII rights by employees following

the common-sense approach of seeking first to resolve

their disputes through the machinery established by the

collective bargaining agreements. The decision of the court

20 While EEOC has not published formal regulations on the

subject, it has announced its interpretation in EEOC Decision No.

70-675, March 31, 1970, CCH EEOC Dec. -fl 6142 (1973), CCH

Empl Prac. Rep. ff 2325.123, and EEOC Decision No. 71-687, Dec.

16, 1970, CCH EEOC Dec. If 6186 (1973), CCH Empl. Prac. Rep.

^ 2325.302. Moreover, it has consistently both accepted and pro

cessed claims its jurisdiction over which has depended upon such

tolling, and has issued right-to-sue letters upon failure of concilia

tion in such cases—as it did, for example, in the instant case. Fi

nally, EEOC has reiterated its interpretation of the statute in its

amicus curiae briefs filed in support of petitioner’s appeal and

petition for rehearing in the court below.

21 Federal officials in the Atlanta regional office of EEOC which

is responsible for processing charges of discrimination arising in

states covered by both the Fifth and Sixth Circuits would _bê con

fronted with accepting and processing charges filed by Mississip-

pians which on the same facts they would reject as untimely filed

if filed by Tennesseeans.

15

below now casts serious doubt as to whether such employ

ees are in fact protected. Unless that doubt is resolved,

civil rights organizations, labor unions, and EEOC, will

have the practically impossible task : to , try to keep em

ployees informed of the danger that if they do not go

through the motions of filing a charge with EEOC while

pursuing their grievance remedies they may lose their

right to sue under Title VII. The difficulty of the task is

compounded by the fact that the message concerning-the

application of a federal statute will be different if the

member of the union or civil rights organization works in,

for example, Mississippi, Tennessee or Illinois.. ;

Procedures of the type involved in this case are common

in collective bargaining agreements involving millions of

workers. Complaining employees are seldom represented

by attorneys at the grievance stage, nor are many of them

knowledgeable as to legal matters. See Love v. Pullman

Co., 404 U.S. 522, 527 (1972). As set forth above, there

has been a steady stream; of reported Cases involving the

principal question raised here—whether pursuit of the

grievance procedures does or does not toll the statute of

limitations for filing charges with the EEOC. In almost

all of thes cases the courts have held that the limitations

are tolled. Congress, in enacting the 1972 amendments to

Title VII, was apparently concerned over the problem of

potential forfeiture of Title VII claims by uninformed

employees allowing the filing period to expire, and indi

cated its approval of the. prevailing tendency of the courts

to ameliorate.. some of the harsher applications of the

limitation.22 , . ,, .

The rule adopted by the Sixth Circuit in this'case is

contrary to public-policy- in that it requires .’the filing of

an administrative , charge! before , it is even, clear if there

22118 Cong. Rec. 7167 (March 8, 1972.).

16

is an act which “aggrieves” the individual, and, if there

is such an act, then before the final scope of that act has

been defined. In a plant which is subject to union griev

ance proceedings, any decision by the employer is tenta

tive until those proceedings have been completed. Until

that time the aggrieved employee does not know what ac

tion, if any, the employer will actually take. The instant

decision requires an employee to file a charge with EEOC

before he or she knows for sure what discriminatory con

duct the employer will undertake or whether he will de

cide to persist in such conduct at all. That rule makes no

more sense than requiring an employee, aggrieved by the

decision of his or her foreman, to file a charge with EEOC

before appealing that decision to higher management.

The courts of appeals holding23 that the amendment to

Title VII passed in 1972 which extended the period for

filing a charge with the EEOC from 90 to 180 days does

not apply to pending charges and litigation is contrary

to the principle “that a court is to apply the law in ef

fect at the time it renders its decision.” Bradley v. Rich

mond School Board, 416 U.8. 696, 711 (1974); Thorpe v.

Housing Authority of the City of Durham, 393 U.S. 268

(1969); see also supra at 11.

The court of appeals ruling that the filing of a union

grievance did not toll the running of the Title VII statute

of limitation for filing an EEOC charge was based on a

misinterpretation of Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415

U.S. 36 (1974) and Johnson v. Railway Express Agency,

Inc., 421 U.S. 454 (1975). Alexander holds that grievance-

arbitration procedures and Title VII actions are inde

pendent in the sense' that utilization of the former 'is

not an election of remedies barring employment of the

latter. The Court, however, makes clear that “Title VII

: 2317a and 525 F.2d at 123. Ut U vl - v : '

17

was designed to supplement, rather than supplant, exist

ing laws and institutions relating to employment discrim

ination.” 415 U.S. at 48-49. And its conclusion “that

the federal policy favoring arbitration of labor disputes

and the federal policy against discriminatory employment

practices can best be accommodated by permitting an em

ployee to pursue fully both his remedy under the griev

ance-arbitration clause of a collective-bargaining agree

ment and his cause of action under Title VII” (415 U.S.

at 59-60) argues against, rather than for, the decision

of the court below that the employee’s pursuit of the

grievance-arbitration procedure should be allowed to re

sult in the inadvertent loss of his rights under Title VII.24

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, is not applicable to

the issue presented. In ruling that the processing of

Title VII charges does not toll the statute of limitations

for 42 U.S.C. § 1981, Johnson holds only that under

§ 1981 the state statute of limitations that is borrowed

is applied in its entirety, including the presence or ab

sence of the possibility of tolling as part of the state’s

statutory scheme. (421 U.S. at 463-64). It has no bearing

upon the question of Congressional intention with regard

to the propriety of tolling of limitation periods provided

in a federal statute.

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, a writ of certiorari should be issued

to review the judgment and opinion of the United States

Court of Appeals for. the Sixth Circuit.

24 At the very least, Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., does not

foreclose the issue adversely to petitioner’s claim. Compare Hutch

ings v. United States Industries, Inc., 428 F.2d 303 (5th Cir.

1970), squarely holding both that institution of grievance-arbitra

tion proceedings tolled the statute of limitations for filing charges

with EEOC and that ah adverse decision in arbitration, did not pre

clude a cause of action under Title Vll.

. Alternatively, ; this petition for a writ of certiorari

should be held pending- the. resolution of McDonald v.

Santa Fe Transportation Company, Brown v. General.

Services Administration, and Place v. Weinberger If

the Court determines that the processing of a union griev

ance tolls the running of the Title. VII statute of limita

tions or that the Title VII statute of limitations period

does not run until after the completion of the grievance

process {McDonald), or that the 1972 amendments to

Title VII should be applied to pending cases {McDonald,

Brown or Place), the Court, should grant the writ of

certiorari, vacate, the. decision of the Sixth Circuit and

remand with, appropriate instructions.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

E ric S ch n a pper

. B arry L. G oldstein

...... 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A. C. W harton

Memphis and Shelby

County Legal Services

Association :

46 North Third Street

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Of Counsel: ..............

A lbert J . R osenthal

435 West 116th Street : '

New York, N. Y. 10025 ~

: 25 As: set forth above; McDonald v. Santa Fe Transportation Qo.f

raises all three of the issues in conflict presented by this petition;

Brown and Place raise a closely analogous issue concerning the ap

plication of the 1972 amendments to Title. V II to charges' and liti

gation pending as of thereifectiye’ date- of : the .• amendiients,., se'g

supra at 7.

A P P E N D I X

l a

I n t h e

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F ob t h e W estebn D istbict of T en n essee

W esteen D ivision

No. C-74-165

O p in io n o f t h e D is t r ic t C o u r t , J u n e 1 2 , 1 9 7 4

D oktha A llen Gu y ,

Plaintiff,

vs.

R obbins & M yebs, I n c . (H tjntee F an D iv isio n ), et al,

Defendants.

M emobandum Op in io n and Obdeb

Defendant has renewed its motion to dismiss plaintiff’s

suit because of her failure to comply with 42 U.S.C. §2000e-

5(d) requiring the filing of a charge with Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Commission within 90 days after the

alleged unlawful employment practice occurred.1 The rele

vant times and acts that took place in this case all occurred

prior to March 24, 1972. The amendment extending the

time for filing 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(e) was prospective in

its application. From the pleadings and memorandum filed

on plaintiff’s behalf, it is clear that she was to report back

1 This provision in the 1964 Civil Rights Act dealing with em

ployment discrimination was amended March 24, 1972, by the 1972

Civil Rights Act. (42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(e)).

2a

to work on October 24, 1971, when ber sick leave expired.

On October 29, 1971, when she returned to work, she found

that she had been terminated on October 25, 1971, as hav

ing voluntarily quit, a status she contested by filing a union

grievance on October 27, 1971. She filed a charge against

her employer with E.E.O.C. on February 10, 1972, assert

ing that the Company’s action was unfair. (She did not

describe it as discriminatory).

“It is true that the statute requires the person aggrieved

to file a written charge within 90 days; it says so clearly

and the courts so hold.” Fore v. Southern Bell Tel. Co.,

293 F.Supp. 587, 588 (W.B. N.C. 1968). See also McCarty

v. Boeing Co., 321 F.Supp. 260 (W.D. Wash. 1970); Younger

v. Glamorgan Pipe Co., 310 F.Supp. 195 (W.D. Ya. 1969);

Gordon v. Baker Prot. Services, 358 F.Supp. 867 (N.D. 111.

1973); and Heard v. Mueller Co., 464 F.2d 190 (6th Cir.

1972).

“It may be conceded that a typical lay-off, without more,

is not a continuing event, but is a completed act at the

time it occurs, so that a charge alleging a discriminatory

lay-off must ordinarily be filed within 90 days thereafter.”

Sciaraffa v. Oxford Paper Co., 310 F.Supp. 891 (D. Me.

1970). From the complaint itself the alleged discriminatory

discharge and refusal to reinstate took ifiace in October,

1971, more than 90 days prior to the charge with the

E.E.O.C. on February 10, 1972. Unless the act complained

about were continuous in its nature, re-occurred after

October, 1971, or unless the period were somehow tolled,

plaintiff is barred because of her failure to comply with

statutory jurisdictional requisites. Choate v. Caterpillar

Tractor, 402 F.2d 357 (7th Cir. 1968); Mickel v. S. C. State

Emp. Service, 377 F.2d 239 (4th Cir. 1967); Sanches v.

Standard Brands, 431 F.2d 455 (5th Cir. 1970).

Opinion of the District Court, June 12, 1974

3a

Senator Everett Dirksen on June 5, 1964, in explana

tion of changes made by the Senate in the House bill,

with particular reference to Section 706(d):

‘New Subsection (d) requires that a charge must

be filed with the Commission, within 90 days after the

alleged unlawful employment practice occurred, except

that if the person aggrieved follows State or local pro

cedures in Subsection (b), he may file the charge with

in 210 days after the alleged practice occurred or

within 30 days after receiving notice that the State or

local proceedings have been terminated, whichever is

earlier. The additional 120 days is to allow him to

pursue his remedy by State or local proceedings.” 11

Cong. Ree. 12297. Banks v. Local Union #136, 296

F.Supp. 1190 (1968)

Tennessee does not have a civil rights law or did not dur

ing 1971 and 1972.

Plaintiff contends, on the authority of Culpepper v.

Reynolds Metals, 421 F.2d 888 (5th Cir. 1970), that the 90

day period is tolled because she filed a grievance directed

toward the defendant company within that period.2 See

Hutchings v. U. S. Industries, 428 F.2d 303, 309 (5th Cir.

1970); Malone v. North American Rockwell Corp., 457 F.2d

779, 781 (9th Cir. 1972); Moore v. Sunbeam Corp., 459 F.2d

811, 826 (7th Cir. 1972). These cases, however, are based

on the rationale that plaintiff should be encouraged first to

try the grievance procedures before resorting to the

E.E.O.C. and that the acts are interrelated in respect to

disputes over discrimination. Dewey v. Reynolds Metals,

429 F.2d 324 (6th Cir. 1970) affirmed by a divided Supreme

2 She also complains that the defendant union failed to represent

her fairly and diligently.

Opinion of the District Court, June 12, 1974

4a

Court, 402 U.S. 689 (1971). Deivey and its progency held

that pursuing a contractual grievance remedy to its con

clusion might estop later pursuit by a claimant of E.E.O.C.

procedures and suit; that the remedies were related and

interconnected. Culpepper, supra, held, however, that

utilization of grievance procedures did not estop, preclude,

or constitute an election of remedies insofar as a grievant

was concerned who might later claim violation of the 1964

Civil Eights Act equal employment provisions.

In 1974, however, the Supreme Court unanimously in

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.,----- U .S .------ , 42 L.W.

4214 (2-19-74) disavowed the Dewey v. Reynolds Metals,

supra, rationale. At page 10 of the slip opinion, the Court

acknowledges that “Title VII does not speak expressly to

the relationship between federal courts and the grievance-

arbitration machinery of collective-bargaining agreements.

It does, however, vest federal courts with plenary powers

to enforce the statutory requirements; and it specifies with

precision the jurisdictional prerequisites that an individual

must satisfy before he is entitled to institute a lawsuit.”

(Emphasis ours.) The Court goes on to hold that grievance-

arbitration procedures neither foreclose nor preclude an

individual’s E.E.O.C. rights and requirements, nor divest

the court of jurisdiction to decide equal employment dis

crimination questions that may arise under the Act. In

other words, “Title VII manifests a Congressional intent

to allow an individual to pursue independently his rights

under Title VII” and other statutes or private contract

remedies, even though these rights have a “distinctly sep

arate nature.” (pp. 11, 13 slip opinion, Alexander v. Gard

ner-Denver, supra). In another place,'pp. 14, 15, Justice

Powell, speaking for a unanimous court says “Title VII

strictures are absolute” and “are not susceptible to pro

spective waiver.”

Opinion of the District Court, June 12, 1974

5a

Since rights under Title VII and under the contract be

tween the parties “have legally independent origins and

are equally available,” it appears that both should proceed

independently and in accordance with their own statutory

or contractual limitations and requirements. The rationale

of Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., supra, persuades this

Court that the 90 day Title VII requirement for filing a

claim with the E.E.O.C. after the occurrence of the alleged

discriminatory event is not effected or abated or tolled by

an independent grievance-arbitration proceeding under a

contract. The E.E.O.C., after all, is required by the statute

in question to attempt reconciliation and negotiation of the

differences before further action is taken. Thus, grievance

and conciliation procedures independently would work for

a settlement and disposition of the disputes between em

ployer and employee. Whether or not an employee files a

grievance, or files an E.E.O.C. charge, he or she still has a

separate right to claim 42 U.S.C. §1981 (1866 Civil Rights

Act) violations. Long v. Ford Motor Co., ----- F .2d------

(6th Cir. 4-30-74). That employee, however, must abide

by applicable statute of limitations requirements as to a

Section 1981 claim, just as he or she must also comply with

contractual or 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(e) prerequisites.

Since plaintiff did not file her claim with the E.E.O.C.

within 90 days after her alleged discriminatory discharge,

defendant employer’s motion to dismiss the 1964 Civil

Rights, Title VII, claim is granted.

This 12th day of June, 1974.

H arry (Illegible)

United States District Court Judge

Certified T rite C opy

J . F r a n k lin R eid , Clerk

By (Illegible)

Deputy Clerk

Opinion of the District Court, June 12, 1974

6a

I n t h e

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F ob t h e W estern D istrict oe T en n essee

W estern D ivision

No. C-74-165

O p in io n o f t h e D is t r ic t C o u r t , J u n e 1 9 , 1 9 7 4

D ortha All e n G u y ,

vs.

Plaintiff,

R obbins & M yers, I n c .

(Hunter Fan Division), et al.,

Defendants.

ORDER ON RECONSIDERATION

The Court on May 30, 1974, entered an order in this

cause dismissing plaintiff’s alleged cause of action under

42 U.S.C. §1981 and overruling defendant’s motion on the

question as to whether the filing of her complaint came

within the 90 day period after issuance of the right-to-sue

letter. (In effect, because it involved a possible factual

dispute, it was held to be appropriate to reserve a ruling

for a hearing on the merits.) Without then expressly so

ruling, the Court indicated that the recent Supreme Court

decision of Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., —— U.S.

------, 94 S.Ct. 1011, 42 L.W. 4214, 1974) “might indicate

that the Union contractual grievance and the E.E.O.C.

claim, being independent of each other, . . . would not

7a

amount to a tolling of nor effect any extension of a [90

day] limitation period. See Johnson v. R.E.A., 489 F.2d

525, 529 (6tli Cir. 1973) reh. denied, (1974) petition for

certiorari applied for.”

Plaintiff moved to amend her complaint, and defendant

Robbins & Myers moved the Court to reconsider and

formally rule on its motion to dismiss alleging plaintiff’s

failure to file her charge with E.E.O.C. within 90 days of

the happening of the alleged discriminatory act on defen

dant Robbins & Myers’ part.

The Court then entered an order ruling on defendant

Robbins & Myers’ motion to dismiss and sustaining it on

the failure of plaintiff to file a claim with E.E.O.C. within

the statutory period. (See the memorandum opinion and

order dated June 12, 1974). Plaintiff has moved that the

Court reconsider this opinion, especially in light of Schiff

v. Mead Corp., 3 EPD #8043 (6th Cir. 1970), unreported.

The Court was aware of this decision, however, when it

rendered its opinion adverse to plaintiff’s contentions. The

primary factor involved there was a change of position on

the part of E.E.O.C. which influenced the Court1 to decide

that the filing of a contractual grievance might toll the 90

day statutory period prescribed in 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(d).1 2

The Schiff v. Mead Corp. ease, however, was decided at a

time that Dewey v. Reynolds Metals, 429 F.2d 324 (6th Cir.

1970) affirmed by an equally divided Supreme Court, was

considered the law in this Circuit. The Dewey rationale

was overruled in Alexander v. Garden-Denver Co., supra.

It was there emphasized that the E.E.O.C. claims and

procedures were' separate and independent and that action

1 (ILS.D.C. N.D., Ohio)

2 Now amended by the 1972 Equal Employment Opportunity

Act.

Opinion of the District Court, June 19, 1974

8a

or conduct taken in behalf of one such claim had no pre

clusive effect on the other. Johnson v. R.E.A., supra, had

held that filing of an E.E.O.C. charge did not toll the statute

of limitations on a 42 U.S.C. §1981 civil rights action. Long

v. Ford Motor Co., #73-1993, ------ F.2d -——- (6th Cir.

4-30-74) held that 42 U.S.C. §2000e (Title VII) actions and

42 U.S.C. §1981 are independent of one another, and, as we

construe it, that the District Court3 was correct in holding

that the Title VII statutory time requirements for filing

a charge were not tolled by the filing of a suit under the

1866 Civil Rights Act. On the other hand, the District

Court’s findings for the claimant under the latter statute

were to be reconsidered on remand in light of McDonnell

Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973).

On the face of the Title VII statute, the only means of

tolling the 90 day period for filing an E.E.O.C. charge after

the alleged discriminatory event was (and is) a filing of a

charge or claim with a state or local agency having au

thority to deal with equal employment opportunities and

discrimination. This plaintiff Guy could not do, because

Tennessee nor Shelby County has any such agency or law

authorizing such a body.

After the discharge in question, Guy had a legal right to

file a grievance against her employer under the Union con

tract, provided she adhered to its terms. Whether or not

she filed her grievance, plaintiff also had a right within 90

days to file a charge of racial discrimination. Within a

year, whether or not she pursued contractual or E.E.O.C.

procedures, she had a right to file suit for alleged dis

crimination under 42 U.S.C. §1981. Plaintiff failed to fol

low through with either of the latter two statutory rights

in accordance with applicable time requirements. Defen

Opinion of the District Court, June 19, 1974

(U.S.D.C. E.D., Mich.)

9a

dant’s motion to dismiss is proper under these circum

stances.

It should he noted that plaintiff did in fact pursue her

grievance through three levels unsuccessfully.4 Further

more, E.E.O.C. investigated her claim and determined on

November 20, 1973, that “the Commission finds no reason

to believe that race was a factor in the decision to dis

charge. . .” Plaintiff waited until the last day of the 90

days given her, or until beyond the ninetieth day in which

to seek the Court’s assistance in filing her Title YII suit

after having received an adverse determination to her

claims since October of 1971. This lack of diligence, in and

of itself, might not constitute a bar, Harris v. Walgreen’s

Dist. Center, 456 F.2d 588 (6th Cir. 1972), but is indicative

of plaintiff’s dilatory role in these proceedings throughout.

See Fehete v. U.S. Steel, 424 F.2d 331 (3rd Cir. 1970) as to

the effect of a negative E.E.O.C. determination involving

“possibilities of sophisticated discrimination . . . because

of European ancestral origin” after an arbitrator’s rein

statement of claimant with back pay—an entirely different

situation from that at bar. Compare Beverly v. Lone Star

Lead, 437 F.2d 1136 (5th Cir. 1971) dealing with this ques

tion where plaintiff filed his claim with E.E.O.C. a week

after the alleged discriminatory event, and within ap

proximately 20 days after an adverse E.E.O.C. determina

tion, filed his suit in federal court.

Mrs. Guy was not “penalized” for her seeking “to adjust

her dispute with her employer through the private

machinery of the grievance procedure” as described in

Malone v. N. American Rockwell, 457 F.2d 779 (9th Cir.

1972). That case did not decide whether there had been a

4 See the findings and conclusions of E.E.O.C. filed as a part of

the record in this cause.

Opinion of the District Court, June 19, 1974

10a

continuing act of discrimination for failure to promote,

or whether the settlement of a grievance was in itself a

discriminatory act with respect to whether claimant had

delayed too long in filing a claim with E.E.O.C. after inter

vening investigation by a state employment opportunities

commission. This Court has granted the motion to dismiss

upon reconsideration, because plaintiff, a Union steward,

did not comply with Title VII statutory time requirements

of filing her E.E.O.C. charge after her termination.

Plaintiff’s claims against the employer, Robbins & Myers,

must stand dismissed.

Certified T rue C opy

J. F r a n k lin R eid , Clerk

By M. Cleaues

Deputy Clerk

Opinion of the District Court, June 19, 1974

United States District Court Judge

Date:

11a

Nos. 72-2144 & -2145

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F or t h e S ix t h C ircu it

A ppea l F rom U nited S tates D istrict C ourt

eor t h e W estern D istrict of T en n e sse e .

O p in io n o f th e C o u r t o f A p p e a ls , O c to b e r 2 4 , 1 9 7 5

D ortha A l l e n Guy

and

I n ternational U n io n of E lectrical, R adio and M a ch in e

W orkers, AFI-CIO L ocal 790,

Plaintiff-Appellants,

v .

R obbins & M yers, I n c .

(H u n ter F an D iv isio n ),

Defendant-Appellee.

Decided and Filed October 24, 1975.

B e f o r e :

W e ic k , E dwards a n d P e c k ,

Circuit Judge.

W e ic k , Circuit Judge, delivered the opinion of the Court,

in which P e c k , Circuit Judge, joined, E dwards, Circuit

Judge, (pp. 8-10) filed a separate dissenting opinion.

W e ic k , Circuit Judge. Appellant G uy has appealed fro m

an order of the District Court dismissing her complaint for

12a

wrongful discharge brought under Title YII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2Q00e et seq.

and 42 U.S.C. § 1981. She claimed that her employer dis

charged her on account of her race (Negro).

The District Court granted the defendant’s motion to dis

miss her Title YII claim on the ground that plaintiff had

not met the jurisdictional prerequisites of §2000e-5(d) of

the Act which were in force at the time.1 The Act required

her to file a charge with the Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Commission (EEOC) within 90 days from the date

of her discharge. She did not file the charge until after the

lapse of 108 days.

The District Court dismissed her claim for violation of

§ 1981 of 42 U.S.C. on the ground that it was barred by the

one year Tennessee statute of limitations. Tenn. Code

28-304.

It was Guy’s contention that the 90 day requirement of

the Act was tolled during the pendency of a grievance

which she had filed with her employer under the provisions

of a collective bargaining agreement entered into between

her employer and the defendant labor Union.

The sole appellate issue is whether the filing of the

grievance tolled the jurisdictional requirements of the Act.

Guy’s claim under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 was controlled by our

decision in Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 489

1 “ (d) A charge under subsection (a) of this section shall be filed

within ninety days after the alleged unlawful employment prac

tices occurred. Except that in the case of an unlawful employment

practice with respect to which the person aggrieved has followed

the procedure set out in subsection (b) of this section, such charge

shall be filed by the person aggrieved within two hundred and ten

days after the alleged unlawful employment practice Or within

thirty days after receiving notice that the State or local agency has

terminated the proceedings under the State or local law, whichever

i's earlier, and a copy of such charge shall be filed by the Commis

sion with the State or local agency.”

Opinion of the Court of Appeals, October 24, 1975

13a

F.2d 525 (6th Cir. 1973), which was affirmed by the Supreme

Court on May 19, 1975, 95 S.Ct. 1716 (1975). Guy has not

appealed from this ruling and it has become final.

The Union originally was a party defendant hut was dis

missed by agreement with the plaintiff and has been re

aligned as a party plaintiff.

The facts pertaining to the Title YII issue were not in

dispute. Guy was discharged on October 25,1971 for failing

to report for work following an authorized sick leave. A

co-worker filed a grievance for her with the employer on

October 27, 1971 which stated: “Protest unfair action of

company for discharge. Ask that she be reinstated with

compensation for lost time.” She did not explicitly claim

racial discrimination. Guy processed her grievance to the

third step under the collective bargaining agreement. The

company rejected the grievance on November 18, 1971.

Guy decided not to proceed further to arbitration. Instead

she filed a charge with EEOC on February 10, 1972 which

was 108 days from the date of her discharge.

The EEOC, although finding no evidence of racial dis

crimination, granted a right to sue letter which resulted in

the filing of the present suit.

The District Judge was of the opinion that this case was

controlled by the recent decision of the Supreme Court in

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974).

While the specific holding in Gardner-Denver was that

the adverse decision of an arbitrator did not foreclose

resort by the grievant to her federal remedy, the reasoning

of the court, in our judgment, supports the proposition

that the filing of a grievance under a collective bargaining

agreement does not toll the limitation period of an appli

cable federal or state statute.

The court pointed out that “in instituting an action under

Title YII the employee was not seeking to review an arbi

Opinion of the Court of Appeals, October 24, 1975

14a

trator’s decision but was asserting a right independent of

the arbitration process.”

The court referred to the legislative history which indi

cated Congressional intent that an employee could pursue

any remedy which he may have under state or federal law.

Thus, the employee could file proceedings under the

National Labor Relations Act or with other federal, state

or local agencies or pursue contractual remedies. In John

son v. Railway Express Agency, supra, the court held that

the various remedies are “separate, distinct and indepen

dent.”

It would be utterly inconsistent with the thesis of Gard

ner-!) enver and Railway Express Agency to hold that the

pursuit of any of these remedies operates to toll other

remedies which the employee has a right to resort to con

currently. See the statements of Senators Humphrey and

Dirksen reported in 11 Cong. Rec. 12297 and quoted in

Banks v. Local Union, 136 Int’l Bhd. Elec. Eng’rs, 296

F.Supp. 1188 (N.D. Ala. 1968).

In Tennessee, Civil Rights remedies are not provided by

state or local law.

Subsection 5(d) of the Act contains an exception when

the grievant has availed himself of remedies provided by

state or local Civil Rights agencies and in such a case ex

tends the time for filing a charge with EEOC from 90 days

to 210 days after the unlawful employment practice or

within 30 days after receipt of notice of termination of

state or local proceedings, whichever is earlier.

Guy would have us add another exception to the Act to

toll the limitations’ period of 90 days when the grievant

resorts to a contractual remedy under a collective bargain

ing agreement.

We are not persuaded that we should add additional

exceptions not authorized by Congress.

Opinion of the Court of Appeals, October 24, 1975

15a

But most important is the language of Mr. Justice

Powell who wrote the unanimous opinion of the court in

Gardner-Denver at 47:

. . . It does, however, vest federal courts with plenary

powers to enforce the statutory requirements; and it

specifies with precision the jurisdictional prerequisites

that an individual must satisfy before he is entitled to

institute a lawsuit. In the present case, these prerequi

sites were met when petitioner (1) filed timely a charge

of employment discrimination with the Commission,

and (2) received and acted upon the Commission’s

statutory notice of the right to sue. 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e-5

(b), (e), and (f).

This is a clear pronouncement that the 90 day limitation

period in the Act for filing a charge with EEOC is a juris

dictional prerequisite “that an individual must satisfy be

fore he is entitled to institute a lawsuit.” Here Guy ad

mittedly did not meet the jurisdictional prerequisite.

The limitation in Title VII is more than a mere statute

of limitations. The Act creates a right and liability which

did not exist at common law and prescribes the remedy.

The remedy is an integral part of the right and its require

ments must be strictly followed. If they are not, the right

ends.

As early as 1886 the Supreme Court recognized the dis

tinction between a statute of limitation and a limitation con

tained in a statute creating liability and imposing a remedy.

In The Harrisburg, 119 U.S. 199, 214, the court stated:

. . . [W]e are entirely satisfied that this suit was

begun too late. The statutes create a new legal liability,

with the right to a suit for its enforcement, provided

Opinion of the-Court of Appeals, October 24, 1975

16a

the suit is brought within twelve months, and not

otherwise. The time within which the suit must be

brought operates as a limitation of the liability itself

as created, and not of the remedy alone. It is a condi

tion attached to the right to sue at all. . . .

In Matheny v. Porter, Price Adm’r, 158 F.2d 478, 479

(10th Cir. 1946), the court said:

. . . Ordinarily, a statute of limitation does not con

fer any right of action, but merely restricts the time

within which the right finding its source elsewhere may

be asserted. I t is not a matter of substantive right. It

neither creates the right nor extinguishes it. It affects

only the remedy for the enforcement of the right. And

unless it affirmatively appears from the face of the

complaint that the cause of action is barred by the ap

plicable statute, limitation must be presented by special

plea in defense. . . .

But here, section 205(e) creates a new liability, one

unknown to the common law and not finding its source

elsewhere. It creates the right of action and fixes the

time within which a suit for the enforcement of the

right must be commenced. It is a statute of creation,

and when the period fixed by its terms has run, the

substantive right and the corresponding liability end.

Not only is the remedy no longer available, but the

right of action itself is extinguished. The commence

ment of the action within the time is an indispensable

condition of the liability. Cf. The Harrisburg, 119 U.S.

199, 7 S.Ct. 140, 30 L.Ed. 358; Midstate Horticultural

Co., Inc. vs. Pennsylvania E. Co., 320 U.S. 356, 64 S.Ct.

128, 88 L.Ed. 96.

Opinion of the Court of Appeals, October 24, 1975

17a

In Callahan v. Chesapeake & 0. By. Co., 40 F.Supp. 353,

354 (E.D. Ky. 1941), District Judge Mac Swinford stated:

The rule is stated in the syllabus from Morrison y.

Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Company, 40 App. D.C. 391,

Ann. Cas. 1914C, page 1026, as follows: “Under the

Federal Employers’ Liability Act of June 11, 1906,

(Fed. St. Ann. 1909 Snpp. p. 585) the time within which

the snit must be brought operates as a limitation of the

liability itself as created, and not of the remedy alone.

It is a condition attached to the right to sue at all.

Time has been made of the essence of the right, and

the right is lost if the time is disregarded. The liability

and the remedy are created by the same statute, and

the limitations of the remedy are therefore to be treated

as limitations of the right.”

Johnson v. Bailway Express Agency, supra, held that the

timely filing of a charge with EEOC under Title VII of the

Act did not toll Tennessee’s applicable one year statute of

limitations. It would therefore appear to us to be utterly

incongruous for us to hold that a federal statute which con

tains jurisdictional prerequisites for the exercise of its

remedies is tolled by the mere filing of a grievance under a

collective bargaining agreement.

Under Guy’s contention the exercise of rights under Title

VII could be delayed indefinitely for many years while an

individual is pursuing other remedies. This contention con

flicts with Congressional intent made manifest by the short

periods of time provided in the Act as prerequisites for the

exercise of the rights.

Guy relies on the following decisions from other Circuits:

Culpepper v. Beynolds Metals Co., 421 F.2d 888 (5th Cir.

1970); Hutchings v. U.8. Industries, Inc., 428 F.2d 303 (5th

Opinion of the Court of Appeals, October 24, 1975

18a

Cir. 1970); Malone v. North American Rockivell Corp., 457

F.2d 779 (9th Cir. 1972); Sanchez v. T.W.A., 499 F.2d 1107

(10th Cir. 1974).

It is noteworthy that all of these eases, except Sanchez,

were decided prior to Gardner-Denver and hence are in

apposite. Sanchez relies on these prior decisions. Sanches

conflicts with Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, supra.

In the brief of EEOC as amicus curiae a new issue is in

jected into the case which was not raised by plaintiff in the

District Court, namely, that under the 1972 amendments to

Title VII it had authority to assume jurisdiction retroac

tively to charges pending before the Commission. It relies

on Love v. Pullman Co., 404 U.S. 522 (1972).

Since this issue was not raised in the District Court by

any party to the case, we are not required to consider it.

United States v. Summit Fid. & Sur. Co., 408 F. 2d 46 (6th

Cir. 1969); Wiper v. Great Lakes Engineering Works, 340

F. 2d 727 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 382 U.S. 812 (1965).

We do note, however, that in Love, supra, the charge had

been timely filed with the Commission so that the jurisdic

tional prerequisite had been met.

Plaintiff Guy’s claim was barred on January 24, 1972.

She did not file her charge with EEOC until February 10,

1972. The amendments to Title VII, increasing the time

within which to file her charge to 180 days, did not become

effective until March 24, 1972. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(e). The

subsequent increase of time to file the charge enacted by

Congress could not revive plaintiff’s claim which had been

previously barred and extinguished.

The judgment of the District Court is affirmed.

E dwards, Circuit Judge, dissenting. Appellant Guy was

discharged for failure to report back to work on her

Opinion of the Court of Appeals, October 24, 1975

19a

production job with appellee Robins and Meyers at the end

of sick leave which had been granted to her. She claims

that she notified appellee that she was not able to return

on the day set, but when she did return four days later, she

was informed she had been discharged.

Promptly on October 27, 1971, the union filed a grievance

on her behalf, alleging that the discharge was illegal under

the union-management contract. This grievance was denied

at the third step on November 18, 1971. Thereafter plaintiff

filed a charge, alleging that her discharge was racially

motivated, before the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission. This charge was filed February 10, 1972, 108

days after her discharge. At the time the EEOC limitation

provided for a 90-clay period within which to file the

charge. On March 24, 1972, however, Title VII was

amended to increase the filing time to 180 days. See 42

U.S.C. § 2000e-5(d). EEOC, in an amicus brief filed in this

appeal, asserts that the 1972 amendment should be read

retrospectively as applicable to appellant’s complaint, since

it was pending in EEOC’s possession at the time when the

amendment became effective 151 days after plaintiff’s dis

charge.

The EEOC position is that the amendment did not create

a new cause of action. It merely increased the period from

90 to 180 days before the limitation became effective.

In Davis v. Valley Distributing Co., ------F.2d ------ (9th

Cir. 1975) (No. 73-2725, decided July 30, 1975), the court,

per Browning, J., held that a similar 180-day extension

amendment (applicable to filing before the EEOC) should

be given retroactive effect. The court said:

The 1972 Act became effective March 24, 1972. The

prior 90-day limitation had run on appellant’s com

plaint some 54 days earlier. It is the general rule that

Opinion of the Court of Appeals, October 24, 1975

20a

subsequent extensions of a statutory limitation period

will not revive a claim previously barred. James v.

Continental Insurance Co., 424 F.2d 1064, 1065-66 (3d

Cir. 1970). But the question is one of legislative

intent; and though not free from doubt, we think it the

more likely conclusion that Congress intended the ex

tended limitations period to apply to all unlawful

practices that occurred 180 days before the enactment

of the 1972 Act, including those otherwise barred by

the prior 90-day limitations period.

Section 14 of the 1972 Act provides:

The amendments made by this Act to section 706

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 shall be applicable

with respect to charges pending with the Com

mission on the date of enactment of this Act and

all charges filed thereafter.

Initially, both the House and Senate bills provided

that the amendments to section 706 would not apply to

charges filed prior to the effective date of the amend

ments. H.R. 1746, 92d Cong., 2d Sess. §10 (1972);

S. 2515, 92d Cong., 2d Sess. § 13 (1972). Section 14 was

adopted primarily to make the new authority given

EEOC to bring suit against alleged violators applicable

to pending claims. EEOC v. Kimberly-Clark Corp., 511

F.2d 1352,1355 (6th Cir. 1975); Roger v. Ball, 497 F.2d

702, 708 (4th Cir. 1974). But Congress did not limit

section 14 of the 1972 Act to the new remedy, although

it would have been simple to do so. The language

of section 14 is sweeping. It includes all amendments

to section 706. Congress was, of course, aware of the