Houchins v. KQED, Inc. Brief in Opposition to Petition for Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1976

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Houchins v. KQED, Inc. Brief in Opposition to Petition for Certiorari, 1976. 15989873-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/43380f1f-94df-4326-9824-8d0a7a362473/houchins-v-kqed-inc-brief-in-opposition-to-petition-for-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

O ctober T e e m ,, 1976.

No. 76-1310.

THOMAS L. HOUCHINS,

P e t it io n e r ,

v.

KQED, INC., e t a t .,

R e spo n d e n t s .

Brief in Opposition to Petition for Certiorari.

W illia m B e n n e t t T u r n e r ,

Pound 502,

Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138,

J ack G reenberg ,

J am es M. N abr.it , III,

S ta nley A. Bass.

10 Columbus Circle,

New York, New York 10019,

A n n B r ic k ,

Suite 2900,

650 California Street,

San Francisco, California 94108.

Attorneys for Respondents.

S u p r e m e C o u r t o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s .

ADDISON C. GETCHELL « SON, INC., THE LAWYERS’ PRINTER, BOSTON

Table of Contents.

Question Presented 1

Statement of the Case 2

A. Proceedings in the Courts Below 2

B. Statement of Facts 3

1. Events Leading to this Suit 3

2. The Guided Tours 4

3. Press Access to other Jails and Prisons 6

a. San Francisco County 6

b. Other County Jails 7

c. San Quentin 7

d. National Policy 8

4. Experience of Other News Reporters 9

Reasons Why Certiorari Should Not Be Granted 9

I. The Court Should Not Exercise Its Certiorari

Jurisdiction to Review an Entirely Reason

able Preliminary Injunction Granted in the

Exercise of the Trial Court’s Discretion 9

II. The Preliminary Order is Not Inconsistent

with Pell v. Procunier and Saxbe v. Washing

ton Post 12

Conclusion 14

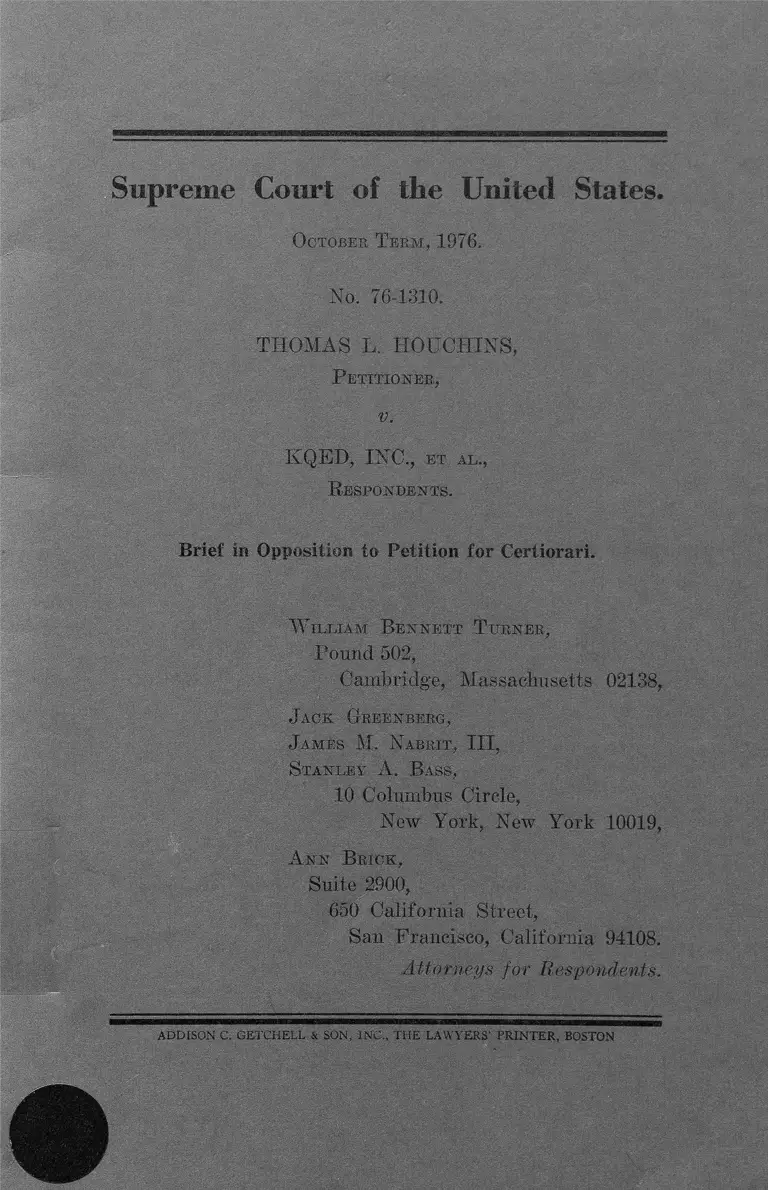

Appendix: San Francisco Examiner, Feb. 16, 1977,

p. 1 15

T able of A u th orities Cited.

Cases.

Anheuser-Busch, Inc. v. Teamsters Local No. 633,

511 F. 2d 1907 (1st Cir.), cert, denied 423 U.S. 875

(1975) 10

11 TABLE OF AU THORITIES CITED

Brenneman v. Madigan, 343 F. Supp. 128 (N.D. Cal.

1972) 2

Deckert v. Independent Shares Corp., 311 U.S. 282

(1940) 10

K-2 Ski Co. v. Head Ski Co., 467 F. 2d 1087 (9th Cir.

1972) 10

Nebraska Press Ass’n v. Stuart, 423 U.S. 1327 (1975) 11

Pell v. Procunier, 417 U.S. 817 (1974) 6, 8,12,13

Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U.S. 396 (1974) 11, 13

Saxbe v. Washington Post, 417 U.S. 848 (1974) 8,12

United States v. O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968) 13

Ot h e r A u t h o r it ie s .

Standard 2.17, National Advisory Commission on

Criminal Justice Standards and Goals 8

11 Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure,

Civil, § 2948 (1973) 10

O ctober T e r m , 1976.

Suprem e Court of tlie United States.

No. 76-1310.

THOMAS L. HOUCHINS,

P e t it io n e r ,

v.

KQED, INC., e t al .,

R e spo n d e n t s .

B rief in O pposition to P etitio n for Certiorari.

Q uestion Presented .

After a full evidentiary hearing, the district court

granted a preliminary injunction enjoining the petitioner

Sheriff from excluding respondent KQED from the Ala

meda County jail, for the purpose of reporting on news

worthy events there, except when exclusion is justified

by jail security. Before this suit was filed, petitioner

completely excluded both press and public. After suit

was filed, petitioner began providing limited guided tours

for the public, and the press was allowed to join the tours.

The district court found that restriction to these tours

unreasonably limited KQED’s ability to gather and dis

seminate information to the public. The court also found

that reasonable access by the press would not result in

2

harm to petitioner’s interests. The question presented is

whether, in these circumstances, the district court abused

its discretion in granting the preliminary injunction.

Statement of the Case.

A. P roceedings in t h e C ourts B elo w .

Respondents (plaintiffs in the district court) are KQED,

Inc. and the Alameda and the Oakland branches of the

NAACP. KQED is a non-profit corporation engaged in

educational television and radio broadcasting. Publicly-

supported, KQED serves the counties in the San Francisco

Bay Area. It maintains a daily television news program

on Channel 9, entitled “ Newsroom.” The members of

the NAACP plaintiffs reside in Alameda County, Cali

fornia.

Petitioner Thomas L. Houchins is the Sheriff of Ala

meda County and operates the county jail. This action

was filed because the Sheriff excluded KQED, as a mat

ter of a general policy of press exclusion, from covering

newsworthy events and questionable conditions at the jail.1

Respondents moved for a preliminary injunction, seeking

to obtain reasonable access to the jail. Numerous affidavits

were submitted with the motion, including the affidavit of

the Sheriff of San Francisco County and several experi

enced news reporters. The district court also held an

evidentiary hearing, where Sheriff Houchins and one of

his lieutenants testified. Respondents presented the testi

mony of the Sheriff of San Francisco, an official from San

Quentin State Prison and three television news reporters,

1 In Brenneman v. Madigcm, 343 F. Supp. 128, 132-33 (N.D.

Cal. 1972), the court found conditions at the jail to be “ shock

ing and debasing,” violating “ basic standards of human de

cency,” so “ truly deplorable” as to constitute cruel and unusual

punishment.

3

to the general effect that press access is freely and rou

tinely provided in other jails and prisons in the area and

that this created no problems whatever for the institu

tions.

On November 20, 1975, the district court granted pre

liminary injunctive relief, providing for reasonable ac

cess by KQED to the jail. The specific methods of imple

menting such access were left to the Sheriff. The Sheriff

then sought and was granted a stay of the order for two

weeks, to enable him to develop procedures for press ac

cess — e.g., searches of reporters and their equipment,

proper identification of press representatives, instructions

as to matters that could not be photographed, consent

forms for interviews, etc. But instead of implementing

any such procedures, the Sheriff filed notice of appeal and

obtained a stay from two judges of the Ninth Circuit. The

appeal was then expedited.

On November 1, 1976, the Court of Appeals unanimously

affirmed the preliminary injunction issued by the district

court. On December 22, 1976, the court below denied the

Sheriff’s petition for rehearing. No member of the entire

Ninth Circuit voted to rehear the case en banc. The Court

of Appeals also denied a stay pending application for a

writ of certiorari, but a stay was granted by Mr. Justice

Rehnquist on January 28, 1977.

B. S ta tem en t of F acts.

1. Events leading to this suit.

KQED’s Newsroom has for many years reported reg

ularly on newsworthy events at prisons and jails in the

San Francisco Bay Area. A large number of stories

have been covered on the premises of the institutions,

with film, video or still camera. Included have been

stories from the San Francisco, Contra Costa, San Mateo

4

and Santa Clara County jails and San Quentin and Sole-

dad prisons. None of this news gathering activity has

ever resulted in any jail disruption or danger of any kind.2

In March, 1975, KQED’s Newsroom reported on a sui

cide of a prisoner at the Alameda County jail. KQED

also reported statements by a jail psychiatrist that condi

tions at the facility were partly responsible for the pris

oners’ emotional problems. The psychiatrist was fired

after he appeared on Newsroom.

In connection with this developing news story, a KQED

reporter telephoned petitioner Houchins and requested

permission to see the jail facility and take pictures there.

The Sheriff refused, stating only that it was his “ policy”

not to permit any press access to the jail. This was also

his response to another television reporter who sought to

cover stories of alleged gang rapes and poor conditions

at the jail.

Prior to the filing of this suit, the Alameda County

jail was completely closed to the press even though the

Sheriff had never even heard of any disruption in any

jail or prison, anywhere, because of news media access.

2. The guided tours.

After this suit was filed, petitioner initiated a series

of guided tours for the public. Each tour was limited

to 25 persons. The tours were booked on a first come-

first served basis. Representatives of the press were per

mitted to go on the tours if they signed up in time. All

six tours for 1975 were completely booked within a week

after they were announced in July. Thus, any reporter

2 In covering stories on location in jails and prisons, KQED

recognizes that inmates are entitled to privacy, and this is re

spected. As a matter of policy, KQED does not photograph or

interview inmates without their consent. When appropriate or

required, KQED obtains formal written consents.

5

who did not instantly sign up for a tour weeks or months

in advance was completely barred from the jail for the

balance of the year.

The guided tours took the tourists through most but

not all of the jail facilities. Excluded was the notorious

“ Little Greystone,” the scene of alleged beatings, rapes

and poor conditions. Also excluded were the “ disciplin

ary cells” in the Greystone facility.

At the outset of each tour, the officials laid down the

ground rules for the tourists. It was forbidden to speak

with any inmates who might be encountered. No photo

graphs were permitted. The Sheriff offered a series of

20 photographs for sale to the tourists, at $2 each or

$40 for the set. None of the photos showed inmate life;

they depicted only selected portions of the plant and equip

ment.

The evidence before the district court demonstrated

several ways in which restriction to the tours unreason

ably limited KQED’s ability to gather and disseminate in

formation to the public:

(a) The tours were completely guided and were ac

companied by several guards. The tourists were of course

shown only what the guards allowed them to see.

(b) Because the tourists were forbidden to speak with

any inmate, they could hear only what the officials told

them and got only “ one side of the story.”

(c) The Sheriff testified that inmates must be kept

“ from sight and communication with the tour group.”

Thus, the tourists never saw normal living conditions

at the jail.

(d) Reporters were not permitted to take cameras with

them. The sterile and unrealistic photos proffered for

6

sale by petitioner gave only an artificial idea of the real

ity of jail life.

(e) Finally, offering only a periodic tour made it im

possible for the press to cover a specific event or follow

a developing news story. News events are evanescent.

They do not coincide with the Sheriff’s schedule of tours.

Limitation to a scheduled tour made it impossible to cover

an escape, a fire, a suicide or other newsworthy event

as it happened.3 It also made it possible for the jail

to be “ scrubbed up” specially for the tour, as was done

for a press tour in the past.

3. Press access to other jails and prisons.

The evidence before the district court showed that other

jails and prisons have no limitations of the kind imposed

by petitioner Houchins, that they routinely provide free

press access and that such access creates no problems

whatever:

a. San Francisco County.

The Sheriff of San Francisco operates four jails. He

routinely authorizes reporters to enter and cover stories

in his jails. The reporters are permitted to bring cameras

8 The Sheriff’s petition for certiorari (p. 9) asserts that re

porters may “ now” have access to cover “ special events, such

as fires or escapes.” Nothing in the record supports this asser

tion. If the assertion is true, it raises a question of what the

Sheriff considers a “ special event” and whether his practice “ op

erates in a neutral fashion, without regard to the content of the

expression.” Pell v. Procunier, 417 U.S. 817, 828 (1974). For

example, information about a recent riot at the jail did not leak

out to the public until nearly two weeks after the event. See

the Appendix to this Brief. If in fact access for spot news events

does not depend on the content of the news, this should be brought

to the attention of the trial court before final judgment, not as

serted without record support to this Court.

7

and tape recorders with them. The Sheriff also permits

interviews of both inmates and staff. Never, on any oc

casion, lias this created any security problems or any dis

ruptions.4

Further, the San Francisco Sheriff advanced affirma

tive reasons, from the point of view of a correctional ad

ministrator, for admitting the press to the jails. He tes

tified that jails “ routinely end up being places that are

extraordinarily and most unnecessarily abusive to people”

and that media exposure of conditions serves to enhance

public awareness and thus motivate county government

to provide adequate funds for more decent facilities.

b. Other County jails.

The evidence showed that KQED and other stations

have done stories on the premises of several other county

jails, without any difficulties or disruptions of any kind.

c. San Quentin.

San Quentin’s Public Information Officer testified about

the press policy of the California Department of Correc

tions as implemented at San Quentin. The Department

recognizes a citizen’s “ right to know,” and provides for

completely open media access to the prisons, with re

porters allowed to bring cameras and tape recorders,

to view all areas of the prison, to talk with prisoners

generally and to interview prisoners of their choice.

The official testified that arrangements for the press to

come to the institution are very simple, and can be made

4 There is no record support whatever for the petitioner’s as

sertion that the Ninth Circuit’s decision will have “ national im

pact” because jailers everywhere will be required “ to do more”

and that this will be a “ burden” for them. To the contrary, the

only evidence of practices in other jails is that press access is

freely allowed and that this creates no problems for the jailers.

8

the same day of the request. San Quentin has experienced

no disruptions or security problems whatever because of

press access. The press could of course be excluded by

the warden if any security problem developed.®

d. National policy

The district court received in evidence the relevant

standards promulgated by the National Advisory Com

mission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals. The

Commission was appointed by the LEAA to formulate

standards for institutions henefitting from LEAA grants.

Petitioner Houchins has received funds from LEAA, in

cluding a grant for the reconstruction of the jail, but he

does not comply with the standards. Standard 2.17 flatly

provides that:

“ Representatives of the media should he allowed ac

cess to all correctional facilities for reporting items

of public interest consistent with the preservation of

offenders’ privacy.”

Current Federal Bureau of Prisons policy is expressed in

the Policy Statement that the Ninth Circuit appended to

its opinion in this case. The Bureau encourages news

media access to all prisons “ to insure a better informed

public.” Reporters may freely use cameras, bring tape

recorders, conduct interviews, etc.* 6

6 In addition to providing open news media access, San Quentin

has frequent tours for the general public, during which inmates

are regularly encountered. The record here shows that the Cali

fornia authorities have completely abandoned the press restric

tion they so vigorously and successfully defended in Pell v. Pro-

cunier, 417 U.S. 817 (1974).

6 As the Policy Statement indicates, the Bureau has completely

abandoned the press restriction it so vigorously and successfully

defended in Saxbe v. Washington Post, 417 U.S. 848 (1974).

9

4. Experience of other news reporters.

The evidence before the district court also included un

successful attempts by other news reporters to cover

stories at the Alameda County jail. One wished to gain

access to the jail to cover stories of reported gang rapes

and suicide. He spoke personally with Sheriff Houehins,

who excluded him from the jail, stating only that it was

his “ policy” not to allow any press entry. The reporter

also tried to get on the first guided tour of the jail in

July, 1975. He promptly signed up but was removed

from the list when someone in the Sheriff’s office decided

that more members of the public and fewer members of the

press would be permitted to go.

Reasons Why Certiorari Should Not Be Granted.

I . T h e C ourt sh o u ld N ot E xercise I ts C ertiorari J u

risd ictio n to R ev iew an E n tir ely R easonable P r e l im

inary I n ju n c t io n Granted in t h e E xercise oe t h e

T ria l C o u r t ’s D isc r e t io n .

Finding that the requirements for a preliminary injunc

tion were met, the district court granted an order that

was carefully tailored to protect the legitimate interests

of all parties. The order preliminarily enjoined the Sher

iff from excluding the press “ as a matter of general

policy.” The order directed that reporters be given ac

cess “ at reasonable times and hours” for the purpose of

providing full and accurate news coverage of jail condi

tions. But, deferring to the Sheriff’s administrative dis

cretion, the court provided that “ the specific methods of

implementing” press access were to be “ determined by

Sheriff Houehins.” Further, the order expressly stated

that the Sheriff may “ in his discretion” exclude all news

10

access “ when tensions in the jail make such media access

dangerous.”

In short, the order is a model of restraint. It does not

grant the press total and instant access on demand. Rather,

the Sheriff may make reasonable time, place and manner

restrictions and may even, in his discretion, deny all ac

cess when he believes that jail tensions would make ac

cess dangerous. Moreover, the district court’s direction

that “ the specific methods of implementing” access are

left to the Sheriff permits petitioner to deal with any ac

tual administrative problem. The district court granted

the Sheriff a temporary stay based on his representation

that specific procedures would be developed to cover such

matters as searches of reporters and their equipment,

proper identification of press representatives, instructions

as to items that could not be photographed, consent forms

for interviews, etc.

The Ninth Circuit unanimously upheld this preliminary

order. A preliminary injunction is of course a matter of

the trial court’s discretion.7 The Sheriff has presented

no reason why this Court should disturb the considered

exercise of discretion by the courts below.

The preliminary injunction was based on a finding by

the district court that respondents — the station and mem

bers of the public — would suffer irreparable injury if

preliminary relief were not granted and that the Sheriff

had failed to show that such relief would result in harm

to his interests. The most important factor, of course,

7 See, e.g., Deckert v. Independent Shares Corp., 311 U.S. 282,

290 (1940); Anheuser-Busch, Inc. v. Teamsters Local No. 633,

511 F. 2d 1097 (1st Cir.), cert, denied 423 U.S. 875 (1975) ; K-2 Ski

Co. v. Head Ski Co., 467 F. 2d 1087 (9th Cir. 1972); 11 Wright &

Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure, Civil, § 2948 (1973).

11

is the irreparable injury suffered by the exclusion of

KQED from covering news stories at the jail.8

A further reason for not disturbing the trial court’s

preliminary order is that it provides an excellent oppor

tunity for definitively resolving all problems relating to

press access before this litigation goes to final judgment.9

Thus, we believe that implementation of the reasonable

access provided by the district court’s order will demon

strate even to the Sheriff that his opposition is not well-

founded. He may then decide voluntarily to change his

policy. During the litigation he may also adjust the pro

cedural details of access. Conversely, if actual problems

are encountered by the Sheriff during the pendency of

this case, that would be a reason for the district court

to deny or limit permanent relief.

8 Mr. Justice Blackmun has reasoned, in considering a restric

tion on reporting by the news media, that First Amendment in

terests are infringed each day the restriction continues:

“ The suppressed information grows older. Other events

crowd upon it. To this extent, any First Amendment in

fringement that occurs with each passing day is irreparable.”

Nebraska Press Ass’n v. Stuart, 423 U.S. 1327, 1329 (1975).

Cf. Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U.S. 396, 404 (1974) (judicial

abstention imposes “ high cost” when First Amendment in

terests at stake).

9 Contrary to Mr. Justice Rehnquist’s observation on the stay

application that the order did not appear to be “ preliminary” to

further proceedings that might modify the injunction, there

are indeed substantial matters that must be resolved in the trial

court before any final judgment is entered. For example, as men

tioned in note 3, supra, the question of access for spot news cov

erage must be examined to determine whether censorship of con

tent must be enjoined. Further, as suggested by the Ninth Cir

cuit, “ to determine the questions of infringement of the correla

tive rights of the public and the media and the means by which

these rights are to be implemented,” the trial court should con

sider in detail how access is handled in other prisons.

12

In sum, this is not the occasion for plenary review by

this Court. Any such review should await a final judg

ment and a complete record.

I I . T h e P r elim in a r y Order is N ot I n c o n sist e n t w it h

P e l l v . P ro c u n ier and S axbe v . W a sh in g t o n P ost.

The Sheriff’s basis for seeking certiorari is his conten

tion that the injunction is in conflict with Pell v. Procu

nier, 417 U.S. 817, 834 (1974) and Saxbe v. Washington

Post, 417 U.S. 848 (1974). He argues that, so long as he

mechanistically equates KQED’s rights with those of the

public in general — wholly excluding both or limiting

both to guided tours — Pell and Saxbe provide him with

a complete defense. This wooden argument was properly

rejected by the lower courts.

The sole restriction on press access upheld by Pell and

Saxbe was a prison rule against interviewing inmates

specifically singled out by the press. The Court upheld

this limited restriction because there was evidence in both

cases that the restriction was necessary to avoid security

problems caused by undue attention to “ big wheels” who

gained notoriety and influence over other prisoners. How

ever, Pell and Saxbe did not authorize any press restric

tions like those maintained by the Sheriff here. Indeed,

the Court expressly pointed out in Pell that “both the

press and the general public are accorded full oppor

tunities to observe prison conditions.” 417 U.S. at 830

(emphasis added). Thus, in Pell the Court noted that

“ newsmen are permitted to visit both the maximum and

minimum security sections of the institutions and to stop

and speak about any subject to any inmates whom they

might encounter.” 417 U.S. at 830. In addition to tours,

13

newsmen were permitted “ to enter the prisons to inter

view” randomly selected inmates. The same was true in

Saxbe. There, the Conrt noted that “ members of the

press are accorded substantial access to the federal pris

ons in order to observe and report the conditions they

find there.” 417 U.S. at 847. In addition, newsmen were

permitted to tour and photograph any prison facilities

and interview inmates they encountered. Id. at 847, n.5.

Thus, the only restriction upheld by Pell and Saxbe

was the rule against the press singling out specific in

mates for interviews, and this narrow rule was upheld

only on a record showing that the press in fact had sub

stantial access to the prisons. As the district court noted

in the present case, the press access actually permitted

by the institutions in Pell and Saxbe is precisely the ac

cess sought by KQED. Absent a showing that such access

would interfere with a valid correctional interest, the

courts below properly found that Pell and Saxbe do not

preclude relief here.

The trial court found that the Sheriff’s policy disables

KQED from gathering nonconfidential information on

matters of public interest. The court also found that rea

sonable access to the jail would not endanger security

or result in any harm to petitioner’s legitimate interests.

Since the Sheriff’s restrictions were found to be “ greater

than is necessary or essential to the protection of the par

ticular governmental interest involved,” the preliminary

order was entirely appropriate. See Procunier v. Mar

tinez, 416 U.S. 396, 419 (1974); United States v. O’Brien,

391 U.S. 367, 377 (1968).

14

Conclusion.

For the reasons stated, the petition for certiorari should

he denied.

Respectfully submitted,

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER,

Pound 502,

Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138,

JACK GREENBERG,

JAMES M. NABRIT, III,

STANLEY A. BASS,

10 Columbus Circle,

New York, New York 10019,

ANN BRICK,

Suite 2900,

650 California Street,

San Francisco, California 94108.

Attorneys for Respondents.

15

APPENDIX

x u m tttt

112th Year No. 215 ■ft 777-2424 WEDNESDA ,̂ FEBRUARY 16. 1977 Daily 20c CITY EDITION

Riot at Santa Rita:

26 women locked up

Battle blamed

on ‘hardcore

troublemakers’

B y D oa M artin ez

Twenty-six women are in Santa

Rita Prison’s maximum security

Greystone section as a result of a

disturbance Feb. 6. Details were

learned only today. ~~

Lt. George Vien, night com

mander at the Alameda County

facility, said all privileges for Santa

Rita’s 140 women were still revoked

as a result of the melee.

‘They’re going to have to earn

back the privileges,” Vien said.

He said the privileges included

commissary, movies, visiting and

television.

Vien said the women in Grey-

stone are hardcore troublemakers

and are being housed in what

usually is the men’s section. Board

partitions and a 24-hour security

watch by a squad of matrons,

isolate the women from male pris

oners, he said

Vien said the women in Grey-

stone include both sentenced and

unsentenced prisoners. Their offen

ses include armed robbery, assault

with a deadly weapon, heroin pos

session and possession of heroin for

sale, auto theft and burglary.

The uprising a week ago Sun

day caused $1,000 in damage and

involved 53 women and a number

of jailers. It was sparked when an

inmate and a deputy started argu

ing in the mess hall.

Sprinklers were ripped from

the ceilings, door panels kicked out

and lockers overturned.

“W e originally moved all 53 to

Greystone where they were locked

in a dayroom,” he said. “Since then,

those prisoners who felt ready to

return to their regular quarters

have been screened and put back in

their regular cells.”

Despite a few skirmishes, the

situation is pretty much normal,

Vien said, and male prisoners are

helping to keep the situation cool

by yelling “shut up” when the

women make noise.